My Shtetele Trashkun

by Berl Glezer (1905-1991)

Completed 15 July 1991 in Bnei Brak, Israel

Dedicated to Miriam and Moshe Krakinowski

Translated from Yiddish by Sonia Kovitz, with heartfelt appreciation to Misha Glezer

✷ See also Berl Glezer in Trashkun in 1989 VIDEO (Yiddish) [1:00]

Part I

go to Part II »

Berl Glezer

| My Shtetele Trashkun | |

| My shtetele Trashkun was small. Tzipa-Hoda and Leyzer-Moyshe lived there along with a hundred other families who taught the blessings to their children. The fathers woke early to pray in shul, then rushed away because they had to work hard for every bit of bread. They worked late into the night. Some made brick ovens, some made windows, some made boots, and some made old shoes new. Some left the shtetl every day to earn a living and came home only when the sun's light had disappeared. |

The mamas believed in miracles for their daughters who had no dowry — a groom! But young people don't believe in mama's miracles. They want a better life. So they sailed to other lands, Brazil, Argentina, America, Palestine, where they found work, and the girls with no dowry found learned husbands. Now, wherever they are, they meet with tears in their eyes as they recall their old home, their papa and mama, their sisters and brothers, whom they will never see again. —Berl Glezer |

Her houses were made of brick and wood. The shtetele was like an island surrounded not by the sea but by broad fields and a thick ancient forest. All kinds of beautiful trees grew in the forest—pine, fir, birch, alder, aspen, ash, and oak—and many kinds of mushrooms and berries: blueberries, bog blueberries, raspberries, and red bilberries.

In early spring a mantel of green covered the fields and meadows. Later corn and rye would come up amid sticks of straw. The ears of corn seemed to lift their heads to heaven. A narrow winding stream ran through the meadow. It wasn't deep and you could reach in with your hand to touch every little clean-washed stone lying on the bottom. There was a wider, deeper place that we called the whirlpool. We went swimming there, especially on Friday afternoons.

The stream, known as Yoste, was where the laundry was washed. The wet clothing was spread out in the meadow to dry. While we waited for it to dry, we gathered fallen goose feathers and various plants—one called bronelkes for making tea, and one with three little leaves known as bobovnik that was a stomach ache remedy. Many other healing grasses grew in the meadow among the yellow flowers. Sunrise and sunset could be seen above the high treetops as if over broad seas.

Montvil estate in 2018 (enlarge, more photos)

Before the First World War began in 1914, all the surrounding fields and woods belonged to a landowner named Montvil. Montvil also owned the land on which the Jewish houses were built. Every year a set amount was paid to him for each little plot of land. His estate was a very efficient operation with a water mill, a small whiskey factory, and many animals. There was a lot of work to be done there, and Montvil hired not just Lithuanian but Jewish workers. His permanent bricklayer and glazier were Jews. After World War I, the fields and woods were taken from Montvil. Part of the land was sold and the rest distributed among the poor.

A window in Montvil's house looked out on the path to the Jewish cemetery. When the body of a deceased person was carried past the window, often Montvil would not allow the coffin to pass. Once a daring young Jewish man wrapped himself in white, climbed into a coffin, and was carried to the window. As expected, Montvil did not allow the coffin to pass. The young man leaped from the coffin and scared him. After that, Montvil built a new path to the cemetery.

We learned the latest news as it was passed from one person to the next. This is how we found out about each death. We knew which young men and women were in love. If someone was a spinster, we knew it was because her parents didn't have money for the dowry. Without money a new family could not establish a home. Matches were often arranged with young men or women from other shtetls.

“Jewish Wedding” fabric collage by Sonia Kovitz (click to enlarge)

All the townspeople were invited to the weddings. As soon as the invitations were sent, people began to bake for the wedding—rich cakes and large twisted loaves called kitkes. The wedding canopy was set up in the synagogue courtyard. On the day of the wedding, a procession of musicians accompanied by townspeople walked from the bride's house, and the groom walked to meet them. If the groom was from another shtetl, he spent the night before the wedding in a nearby village. The next morning the musicians would travel in a wagon loaded with whiskey and refreshments to greet the groom and bring him to the wedding. The festivities usually lasted two or three days.

Once something happened like this. The groom who was to marry Gitka daughter of Shneyer-Mote arrived in the village and was met by the musicians. The groom asked them to give him the promised dowry then and there. Of course the musicians had not brought the money with them, so the groom refused to go to the wedding. At Chaya-Sora [Konkurovich]'s house the prepared tables and the entire community waited, but there was no groom. Only after the money was delivered to him did the groom show up. If Gitka weren't so worried about ending up a spinster, she would have refused to go ahead with the wedding after his behavior.

Two Jewish newspapers were received in Trashkun—one by Nachman [Lichtin] son of Peshe, who had been a soldier under Czar Nikolai II, and another by Nachman's good friend Mote Degutnik. Nachman also had a library in his house for a while. On Sabbath afternoons guests would drop by the home of one or the other to read the paper, although few were interested in politics. People didn't want to know much about politics since they already had enough worries of their own.

In later years, when more newspapers were being written and read, the shtetl residents, especially the younger ones, wanted to know what was going on in the world. We improved the life of our shtetl by forming community aid societies that granted interest-free loans, arranged evening classes for yeshiva students with daytime jobs, or performed the ritual burial preparations.

✡ Holidays ✡

The Jewish holidays were observed beautifully in our shtetl Trashkun—not in a small way, but with everything that was proper. Every holiday had its own special kind of challah. On Rosh Hashanah a braid was laid on top of a round loaf, and for Sukkos, three twisted braids were arranged on top. Before Pesach we collected money to donate to the community fund for providing the poor with matzo and wine. On Pesach hot kneydlech [matzo balls] were prepared. When they were brought to the table directly from the hot stove, they were delicious! During the eight days of Pesach we did not work or play. For the 49 days of counting the omer [a biblical measure of grain], from the second day of Pesach to Shavuos, no weddings were held and the young men and women spent less time together. But on the 33rd day, Lag B'Omer, weddings took place and children painted colored eggs. Shavuos was celebrated beautifully. Dairy dishes such as cheese blintzes and sweet dessert loaves were prepared. Green branches decorated the doors of the houses and the horns of the cows from the fields.

During the days of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, we pondered our actions and hoped that the Master of the Universe would forgive our sins. No one sinned deliberately, it seemed. On Rosh Hashanah we did not eat until after the final long blasts of the shofar. The women and girls felt faint as they ran to hear the shofar at the end of the service. On the day before Yom Kippur, the repentence ritual of waving a fowl was performed, always with white roosters or hens. Before going to the synagogue, the men took a good bath and performed the ritual of self-flagellation. They hoped that the blows they endured would be taken into account in heaven and their sins regarded more favorably. On Yom Kippur everyone fasted, young and old, men and women, without distinction. Many tears were shed during the recitation of the prayers. In those days many women were not able to read. They came to the synagogue to hear the prayers read aloud and they repeated them.

Immediately after Yom Kippur we began to build sukkes [temporary dwellings] for the holiday of Sukkos. We decorated them beautifully. The sukke was placed near the kitchen window so that meals could be easily handed in and out. Each day of Sukkos the shammes [synagogue caretaker] carried the esrog [yellow citron] to every house so that the women and children could say the blessing over it.

When Simchas Torah arrived, lanterns for the little ones were made from beets with a small candle placed inside each one. The children went with the grown-ups to the Torah scroll procession. The singing and dancing went on until late in the evening. On the day of Simchas Torah, people who didn't drink whiskey the rest of the year would get drunk. After the service, the men made the rounds of all the houses, where tasty dishes would come out of the oven. The visitors danced on the tables and asked very nicely to be invited to eat.

For Chanukah we bought fatty ducklings. The schmaltz [sautéd skin and fat] was set aside for Pesach, but the gribenes [cracklings] were eaten during the eight days of Chanukah. People made latkes, played card games, and spun the dreydel. Boys and girls went for sleigh rides on the freshly fallen snow. Sometimes the sleighs overturned, with much shouting and laughter, in the ditches along the side of the road

The last holiday I will write about is Purim. Everyone went to hear the reading of the Megillah. Some children were armed with marbles that they shot through cylinders, and others had noisemakers. People sent Purim gifts of food and drink to each other and went to each other's Purim feasts. Together the community made calf's-foot jelly from a calf's head and feet.

The Jewish holidays and delicious dishes from my childhood, although so beautiful for me, are painful for me to recall now. There are other events from my childhood in my shtetele Trashkun that I will describe—all that has remained with me in memory from those years.

Who lived on which streets, and

what work did we do in our little shtetele Trashkun?

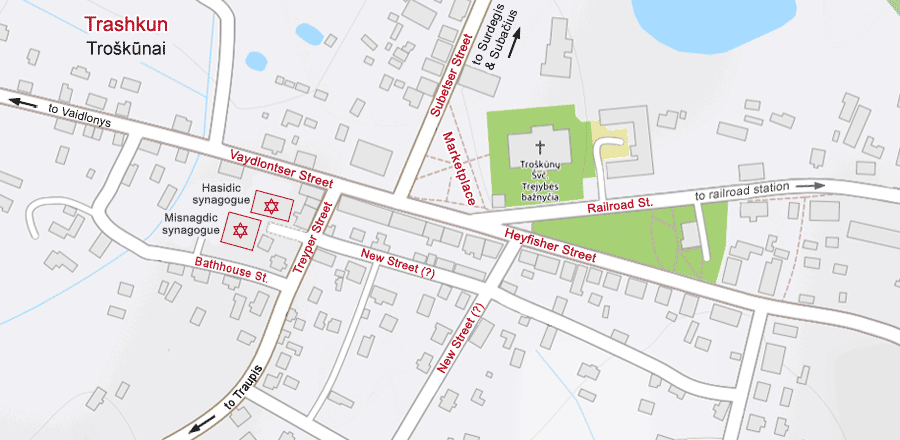

Street names used by Jews before World War II. Click for map with Lithuanian street names. (Map based on Open Street Map.)

Heyfisher Street [Vilniaus gatvė] (map): For a time our family lived in a house owned by a Polish citizen, the first house on Heyfisher Street. Near the house was a deep pond, half-covered with greenish water. We could hear frogs croaking in the pond in the evening. The women used the clean part of the pond for washing clothes. They waded into the water up to their knees and placed a bench on which to beat the laundry with a wooden paddle. Then they stretched out each piece to dry in the nearby meadow. Sometimes the women went home for a bite to eat while the laundry was drying and told each other stories.

The next house on Heyfisher Street belonged to Fayve son of Moyshe [Solomon]. He was a merchant, and I think they had two sons and two daughters. Their first son went to America, and the second son to Russia, where he settled in the city of Sverdlovsk. The daughters married and remained in Trashkun.

Nachman Lichtin was a big merchant and had a very nice house. He had four sons and two daughters. One son and one daughter left for America before World War I. Nachman's house, which held the czarist government's local liquor monopoly for selling whiskey, served as an inn where traveling preachers, bridegrooms, and other visitors could spend the night. The courtyard was fenced with high planks. In the days before Pesach you could hear from the other side of the fence the gobbling of turkeys being readied for the holiday. Nachman's house burned down during World War I. After the war Nachman and his family moved to Ponevezh (Panevėžys), but later, on the same spot in Trashkun where his old house once stood, he built a new house and was able to sell it very quickly. Rafaelke son of Hirshe [Glezer] bought the house.

In the next house Yashe-Gershon son of Bentze-Shimen lived with his wife and children. He was a merchant, and an aging bachelor when he finally got married. Next on Heyfisher Street lived Yeshoye-Leyb [Yakobson] the butcher. They had a daughter Dverka, who married in the shtetl Vidishok (Vidiškiai), and a son Motke. Another son and his wife bought the pharmacy and lived there. Later Rivka daughter of Buna-Gitl [née Berk] lived there and had a store. Rivka married Shayke (Ishaye) son of Abram [Puner]. Later Rivka's sister Roska became proprietor of the store.

Near the store lived Meir son of Khonel [Glezer], a bricklayer who built a brick house and lived there alone. His wife [Chaya Feyga Kovnovich], the sister of Shleyme son of Getze [Kovnovich], died very young. Meir had two daughters, Nechka and Sorka. He and his daughters were on very bad terms, and the daughters moved out when they were still young. Nechka was a very beautiful girl. It seems that she fell in love with a Russian officer in Riga and lived with him until the end of World War I. She had a very nice life until the early days of the Revolution, when her husband, the officer, was arrested and shot. After that, Nechka remained alone. Meir's second daughter, Sorka, lived in Ponevezh but never once visited her father.

Shmuel Levinson built a nice house near Meir's house. He was a big merchant who was very rich, and in addition he won 10,000 lita on a lottery ticket. He married a woman who was born in Russia, a very intelligent woman. They had two sons, but one of them died at a young age. Shmuel liked to spend time with other women, especially with Feygetzka daughter of Ortzik [Sapozhnik]. Later Hirshke son of Hinda, also a big merchant, bought Shmuel's house. Hirshke married a girl from the shtetl Kavarsk (Kavarskas).

Right next to Shmuel Levinson's house was Chatzke Saltuper's brick house. Chatzke was a very fine householder of the shtetl. For a long time he was business manager for the landowner Montvil. He had two daughters. When World War I ended, the younger daughter, Yudis, traveled to Germany to study and married a young Jewish man there who was born in Russia. They moved to Russia when World War II broke out. Because of the political views of Yudis's husband, he was sent to Siberia, where they both lived until 1960. From Siberia they went to live in Vilna and bought a house with an orchard and a large garden. They had one son, who studied and married in Leningrad. Chatzke's older daughter, Ester, never married. She and her mother were killed by the Lithuanian fascists.

Bere son of Pesha, whose last name was Lichtin, was Nachman's brother. He was a very nice householder of the shtetl. His brick house stood where the central street of the shtetl began. He had two daughters and a son. In 1916 Elka went to Leningrad, where she was struck by an automobile and died. Itka and her husband Azriel Dich sold their house and moved to Africa. Bere's son left for America right after World War I.

Bere's house was bought by Chaim, whose last name was Labo. His nickname was Chaim the Dupe, but he was no dupe. Chaim was a shoemaker and saved 10,000 lita to buy the brick house. When the Jews of Trashkun were taken to Ponevezh by the Lithuanian fascists, along the way his wife was tragically murdered after giving birth to a child.

Berk family's two-story house (description)

The two-story brick house belonged to Zalman Berk's son Yoshke [Abram Yosl]. Yoshke spent a lot of time gardening. You would see him standing in the garden with his trousers rolled up to his knees, watering the tomatoes and cucumbers. Next to his house was an iron business.

Leybe Kikhel, Kopel Miron, Yisroel Beyner, and Avrom Lichtenstein lived in the next row of brick houses. Each one had a shop in his house.

Then came Yoshe Saltuper's large brick house, where he sold textiles. Their daughter moved to Leningrad. Yoshe was a feldsher [unofficial medical practitioner] and treated people who had various illnesses. He himself died of a lung infection. Farther along past Yoshke Saltuper's house was a large brick house that belonged to a Lithuanian named Beradisius.

Vaydlontser Street [Dariaus ir Girėno gatvė] (map): At the beginning of Vaydlontser Street stood the house of Yankel son of Paya [Kushner]. His son Shleyme was a butcher and his wife Dobra was the buyer of the meat for their butcher shop. Shleyme and Dobra had six daughters and two sons. Their oldest son, Elke, became a makher [big shot] when Soviet rule came to Trashkun.

Near their house was the Hasidic synagogue, and a little farther on, the Misnagdic synagogue.[NOTE]Hasidim, followers of the Baal Shem Tov, emphasized ecstatic singing and dancing, while the Misnagdim, their opponents, followed the Vilna Gaon in upholding traditional rabbinic Judaism. The two synagogues were considered the spiritual center of the shtetl. People went three times a day to pray, and took the children with them on the Sabbath. Rabbis and traveling preachers visited the synagogues and gave religious talks.

Hasidic synagogue in Trashkun

Misnagdic synagogue in Trashkun

The house of Nochum [Chaimovich] the shoemaker was next to the Hasidic synagogue. They had three sons and two daughters. One son left for Brazil, and one daughter, Beylka, left for Palestine in the 1930s and worked on a kibbutz. In 1963 she came to visit her brother and sister in Vilna (photo).

Nochum's brother Gimpel [Chaimovich], who lived nearby, worked as a business manager for Binyomin Yoffe, the lumber merchant. Gimpel also had a family of good size, but there was no work for the children in the shtetl so the children moved to Kovno (Kaunas) to find work.

Next to Nochum's house was a wide ditch whose water flowed into the stream Yoste. Nechoma daughter of Hirshe [Glezer] lived on the other side of the ditch, and Daniel Shenkman, a shoemaker, lived farther back in the yard. Moyshe the melamed lived near the ditch since before World War I, but on a side path. I attended his cheder.[NOTE]melamed: children's Hebrew teacher

cheder: Jewish primary school. A friend of Moyshe's lived in a village eight kilometers from the shtetl. Their family was attacked in the middle of the night and murdered by drunken Lithuanians.

Still farther along on Vaydlontser Street lived Moyshe-Ruven, whose last name was Berman. They had one son and three daughters. They had machines for combing wool in their house. One daughter left for America in 1911. Their son Hirshl worked as a cashier in the Jewish folksbank [Jewish community bank].

Next was the house of Leah Toyba, “Leah the Dove.” Her house had a large orchard of apple trees with burdock growing nearby. Yankel Nurkin had two sons, Chaim-Lipke and Motke. They all went to Palestine, where they spent the rest of their lives. Before World War I, Abba the tailor lived in Nurkin's house. Abba had a son who was also a tailor. They went to Brazil in 1925.

Yankel son of Mera-Mina lived in the last house on the same side of Vaydlontser Street. When I was a boy, I liked to visit their attic where for five kopeks you could buy a glass of 100 grams of syrup. During World War I their family was evacuated deep into Russia. They did not return to Trashkun after the war.

Avrom-Itze [Chaimovich] the blacksmith lived in the first house on the other side of Vaydlontser Street. He no longer smithed shoes for horses, but made items from iron. He had four sons and one daughter. One of the sons, Chaim, was a revolutionary. Even before the time of Nikolai II, the czarist police looked for Chaim to arrest him, but he hid. Later, in 1917 during the Revolution, I was in Penza and saw Chaim taking part in a demonstration. He was holding the red flag and walking in the first row.

Shmerl [Glezer] the tailor, my uncle,[NOTE]Technically, Shmerl was Berl Glezer's great-uncle. lived in a house close to the marketplace. When I was in the first year of cheder I went to see Uncle Shmerl to ask for Chanukah gelt. He told me I was too late—it was dark outside and already the night of the fifth candle—but nevertheless he gave me Chanukah gelt and told me not to be late next year. During World War I his entire family went to Russia, and all of them died there. Bine the shoemaker [Binyomin Itzikovich], son of Oren, lived in the same house as my Uncle Shmerl. Bine's son Berke [Dov Ber Itzikovich] went to Africa.

Eyzer, the kosher butcher, lived in a house farther down the street. His son-in-law Reb Shneyer [Reznikovich], a very devout and good person, lived with him. Reb Shneyer would sit in the synagogue and study all day until late in the evening. Every Friday Reb Shneyer went to Beylka's and chose baked goods for families who did not have money to buy challah for the Sabbath. Two brothers, Elke and Berke, whose family name was Skudovich, also lived in this house. [ VIDEO remembrance of Reb Shneyer ] [ Berke/Berel Skudovich is mentioned in Sholom Eyzer's account of the 1915 pogrom in Trashkun. ]

On the other side of the ditch lived Yudel, who had a son who was deaf. Living in the same house as Yudel was Leyzer-Moyshe [Klatzko] the wagon driver, his wife Tzipa-Hoda, and their four sons. Their son Noske married Roshka-Sora, daughter[NOTE]Roshka-Sora was the granddaughter Sora-Feyga and Gershon Katz. Her mother was Dina Katz, née Beiner. of Feyga. The house of Leyzer the shoemaker was higher up along the ditch. One of their sons drowned in Aniksht (Anykščiai). Leyzer and his entire family went to Brazil.

Miriam (Merele)

Shumacher

(enlarge)

photo: Yad Vashem

Farther along was the house of Chaim Shumacher and his wife Perl. He played a prominent role in the shtetl and they had a very nice family. Their oldest daughter Merele was a very pretty and smart girl. She lived in Kovno the year before the war. After the war Merele married Moyshe Krakinowski. Now (1991) they live in America.[NOTE]It was Merele/Miriam Shumacher Krakinowski and her husband who urged Berl Glezer to write this memoir, and the memoir is dedicated to them. Her parents Chaim and Perl were the first in the shtetl to be shot by the Lithuanian fascists. They were buried along the edge of the cemetery, along with Ruvke and Hirshke sons of Velve [Itzikovich], Noske and Tevke sons of Leyzer [Klatzko], and Feyga wife of Binyomin [Krasovsky] the tailor. [See written account by Itzhak Konkurovich and VIDEO account by Miriam Shumacher Krakinowski.]

A memorial with the inscription “victims of fascism” was placed at the grave, with flowers planted around it, surrounded by a beautiful little fence. Lithuanian children from a nearby public school used to come often to water them, but in recent years the memorial was neglected. The fence was broken and grown over with branches and the flowers were no longer watered. In the last days of August I often came to this spot with my son Isaac, who would chop down the branches that obstructed the memorial.

Itzik Konkurovich visits his family's home

in Trashkun after the war (1947) (enlarge)

The second house from Chaim and Perl Shumacher's house belonged to Chaya-Sora. Her family name was Konkurovich. She had ten children—six daughters and four sons. Her husband went to Africa in 1912 and later sent for four of the daughters and one son. Chaya-Sora and the rest of the children stayed in Trashkun. They had a very large house where weddings were held and where traveling preachers could rent a room. Chaya-Sora and her daughters were all teachers. You could always hear laughter coming from their house.

Three more families lived on Vaydlontser Street. Shneyer-Mote had two daughters, Gitka and Minka. Shneyer always had a sour face. When he was asked why he always looked so sour, he replied that that's how his face was. Chaim [Vinik] son of Sora-Gita had two children who both went to America. The daughter of Freydl [Vinik] married Zavel Martsushky. This was the end of Vaydlontser Street.

Church opposite marketplace in the center of Trashkun, 1925

(enlargement and 2018 photo)

The Marketplace [Independence Square, Nepriklausomybės aikštė] (map): Here is where the marketplace began. A cross stood at the center of a beautiful wooden fence. Across from the marketplace was a church with a bell, encircled by very old elm trees. The priest's household was located behind the church. Every Thursday people came to the market. The farmers brought their products to sell to the shtetl: corn, wheat, barley, oats, peas, cheese, butter, as well as animals and birds.

Fishl Levin and his wife Reyzl lived across from the church. They had three daughters and two sons. The oldest son, Sholemke, hid from the Lithuanian fascists in the forests until they shot him in 1944. One daughter was evacuated deep into Russia. She now lives in Ponevezh with her husband and two daughters, who both married Lithuanians. Another of Fishl's daughters who survived was named Leyka.

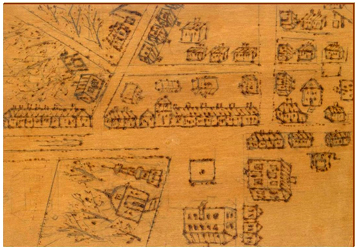

Berl Glezer's electro-pencil engraving of Trashkun marketplace

Across from the marketplace stood the house of Yeshoye-Leyb, whose last name was Yakobson. He had three sons and two daughters. One daughter [Chayka Basa] stuttered a little. She married Hilke [Yechiel] son of Gershon [Solomon], and they lived in her father's old house. Yeshoye-Leyb's son Yulke [Mendel] married Leah Klor from the shtetl Shirvint (Širvintos). They fell in love and married without a dowry, and lived with her father in the new house that he had recently built.

Subetser Street [K. Inčiūros gatvė; Šiaulių gatvė in the interwar years] (map): In earlier years, Shabse son of Yankel [Bageyler] lived in the first house on Subetser Street. Shabse had four daughters, all of whom went to Africa. Many years earlier, Yudis [Beyner] and her daughter Tzipka and son Bentzke lived in Shabse's house before going to Canada. Later Asher the shoemaker and his family lived in Shabse's house.

Hene son of Rashe, a bachelor, was a kosher butcher and spent time with Chayka daughter of Binyomin [Krasovsky]. When Chayka left for the hakhshore[NOTE]agricultural training for Palestine to prepare for life in Palestine, Hene stopped working as a butcher and went there too.

The house of Ortzik [Sapozhnik], son of Rashe, was next. The family baked bread to sell. There were four daughters and a son. The son was an engineer who worked in Kovno, and three of the daughters went, I think, to Canada. The three who left were Peska, Roska and Tzipka-Yentka, and Feygetzka stayed in Trashkun. As I wrote earlier, Shmuel Levinson spent time with Feygetzka daughter of Ortzik. Very late one summer night Feygetzka was nowhere to be found. Her husband Syome [Levin] stood on his doorstep shouting loudly, “Fenya!” That is what he called her. There was no answer. Even though it was late at night, we young people were still out strolling in the street. When I escorted Ortzik's daughter Tzipka home and opened the gate, there were Feygetzka and Shmuel behind the fence.

Ortzik's garden and Hinda [Kozhenetz]'s garden were side by side. The ownership of the well between the two gardens was contested in a lengthy court proceeding. Hinda had five daughters and two sons. The first daughter, Tamara, married Avram son of Lozerke [Lichtenstein] when she was no longer young. It was a disaster. Khonke went to Canada and Freydl got married in the shtetl Tauvian (Taujėnai). The other three girls did not marry.

Yashe son of Hirshe [Kozhenetz], a brother of Hinda's husband [Ovsey], had a new house built by his son Nosn. Yashe's wife's name was Golda [née Itzikovich]. They had four sons and two daughters. Three sons went to America before World War I, and the fourth son Noske married Rivka, the oldest daughter of Gershon son of Moyshe [Solomon].

Glika had a daughter named Beylka. When the Red Army was in Trashkun in 1940, a Jewish Red Army soldier promised to marry Beylka, but deceived her and left. Glika's sister Rochka was a very pretty girl who went around for a long time with Danilke Fayvish. Everyone was sure that Danilke would marry her, but one fine morning he left for Canada. Rochka later married another Danilke, whose last name was Shenkman.

Velve [Itzikovich] the shoemaker built a new house on Subetser Street. He had three sons and a daughter. Velve would sit with his sons Hershke and Ruvke until late at night, hammering nail after nail into boots needing repair. The daughter Muska married a young man from Utyan (Utena). A lot of money was given for the dowry, but their life together was not good.

Farther along the street was the house of Leyb the shoemaker, another son of Hene, son of Rashe. They had two sons and one daughter. The oldest son, who lived in Kovno, got married in the first days of World War II. Leyb and his wife went to Kovno for the wedding, but the war made it all come to nothing. Hirsh the miller and Bentze [Segal] son of Shimen used to live on Subetser Street where the Jewish houses came to an end. Hirsh had a windmill. Later Hirsh and his entire family went to Africa.

Treyper Street [Traupio gatvė] (map) began with the house of Paya [Rutenberg, née Kushner] “the goat.” They called her the goat because she had white hair. She had three daughters and one son. Her husband [Israel Rutenberg] was shot in 1919 by Lithuanian partisans. The oldest daughter and son went to Canada. Merka married an intellectual young man from Ponevezh. Rochka went to the hakshore to prepare for life in Palestine, even though she didn't have a permit to go, and later she went to Palestine.

Motl Degutnik and Pine Sherman shared a brick house. Mote, a leader in business and an assistant to the rabbi, organized the Jewish folksbank in the shtetl. Mote's wife Sheva, who was not young when she died, did not bear him any children. [See reference to Sheva Degutnik in account of 1915 pogrom.] We often gathered at Motl's and Pine's house in the evenings to spend time with Pine's son Nochumke. Freydka daughter of Zalman, who was married, would be there too. Sometimes she sneaked through Pine's attic, which connected to Mote's attic, to spend time with Mote. Very late one evening Freydka's husband Moyshke got tired of waiting for her and walked through the entire shtetl looking for her. He decided to watch to see where she came out, and he caught her leaving Mote's place. Later Mote married a second time. I think his second wife gave birth to two daughters.

Pine [Sherman] and his wife Buna-Rela had three daughters. At the beginning of World War I, many Jewish families of Trashkun were evacuated deep into Russia, but not Pine and his family, who remained in Trashkun. During the period of the German occupation he worked very hard and became very rich. He baked bagels and sold them in a market stall.

In 1920, after the war my cousin Hirshl, son of Leybe [Shepshelevich] the shammes, fell in love with Pine's oldest daughter, Liba (Luba). Liba and Hirshl got married against the wishes of their parents [read more]. Liba gave birth to two girls whose names were Frumele and Chavele. In 1925 the family went to Brazil.

Nechama Puner

Farther along, in the direction of the stream Yoste, was the house of Itzke son of Berchik [Yuzent], who married Chanka daughter of Fishl [Levin]. The last house belonged to Avrom, son of Mordche. Puner was their last name. [Read about Avrom Puner.] They had four daughters and three sons. One of them, Nechomka, went to Palestine to join her fiancé Leybke son of Eleber [Zalk] in 1932. They got married when she arrived.

New Street [J. Basanavičiaus gatvė and/or Žemaitės gatvė] (map): In order to tell who lived on New Street, I will begin on the east side. Three [Shmit] brothers—Khone, Mende and Hirshe—lived in the first three houses. Khone was a cook, Mende and Hirshe were shoemakers. All of them had beautiful, successful children and grandchildren.

Behind their houses was the large garden of Gershon [Solomon] son of Moyshe, who owned two houses. One was a new house that still needed windows and doors. Gershon was a big flax merchant and the new house was always full of the flax he bought. The workers were mainly Lithuanian women hired to scutch the flax.[NOTE]Scutch: beat the flax with a swingle to remove the fibers from the stalks. Gershon himself sorted the flax—he was an expert at it. He had four daughters and three sons. When his wife died, the oldest daughter, Rivka, became mistress of the household. Later she married Noske [Kozhenetz] son of Golda. The youngest daughter, Elka, married before the rest of her sisters. Sora-Leyka was a very pretty girl and Hirshke son of Velve [Itzikovich] was in love with her. She was evidently very fond of him too, but she was the daughter of a big merchant and Hirshke was a worker, which prevented her from marrying him. They went for walks in the evening so that no one would see them together. Moneske, Gershon's youngest son, went to Africa, and the oldest, Hilke, married Chayka daughter of Yeshoye-Leyb [Yakobson]. I learned from Merele daughter of Perl [Shumacher] that the middle son Shabske hid in the forest until 1944, when the Lithuanian fascists found him and shot him. [Read more about the Solomon family.]

Gershon [Katz] the shoemaker and his wife Sora-Feyga lived on the other side of New Street. They had three daughters and two sons. The older son fell in love with a Lithuanian shikse [non-Jewish woman]. The younger son, Yisrolke, married [Dina] the daughter of Yisrael son of Lipe [Beiner]. He was a very strong young man, and in the first days of the war he fought the Lithuanian fascists. They removed the wrappings from his hands leaving the skin bare, then shoved him onto his knees and made him crawl across broken glass. Their daughter Roska married Noske [Klatzko] son of Tzipa-Hoda.

Farther along was Ayzik [Kozhenetz]'s house, which had a tin roof and a garden where many varieties of apples and black currants grew. Ayzik never sold the apples or berries but gave them to everyone for free. Until World War I ended, he was very rich. He had a profitable lumber business and owned two horses, a cow, and some sheep. During the war Ayzik didn't leave.[NOTE]Most Jewish families in Lithuania were forcibly resettled in the east during World War I. He had two sons and three daughters. Chaya, his second wife, died very young, and from that day on, everything was over for his family. He was entirely broken by her death. He became sick and could not carry on his business. The children were all young, and responsibility for the entire household fell to the oldest daughter Freydka, who was 10 years old. She had to transport corn, bake bread, milk cows, and do a lot of other work. Her younger sisters Peska and Bunka were still small, and brothers Shike and Khonke were a little older. In 1925 the brothers joined their uncles in America. [Read more about Shike and Khonke.] Peska went to Palestine in 1937. The surrounding neighbors sympathized with the great tragedy of Ayzik's family and their business losses. I was very young at that time and thought Freydka deserved a good future because of all the difficulties she had faced in her early years.

Itzik Yoffe lived to the left of Ayzik in a nice house with a large orchard and a deep pond in a garden. Itzik bought geese and sold them in Germany. His son Binyomin, a big merchant, finally got married when he was already an elderly bachelor. Itzik's older daughter [Chana-Sora] got married in Vilkomir (Ukmerge) and the younger one, Chaya-Bashl, married a yeshiva student who boarded with the family. Chaya-Bashl had two sons, Shmulke and Sholem-Gezhke. They built a small house across from Itzik's orchard.

Berl Glezer used an electro-pencil to engrave these Trashkun street diagrams into wood, working from memory (Israel, 1991).

The next house belonged to Bertzik [Yuzent] the bricklayer. It was of good size and had a large garden. Bertzik had four sons and two daughters, but one daughter died at a young age in Russia during World War I. One son lived in Shadeve (Šeduva) and another son, Avromke, went to Palestine in the late thirties. Their son Nosn was also a bricklayer. His wife Dveyrl was my sister. They had one son and five daughters. From their entire beautiful family only one daughter, Zelda, survived because she was with a lot of other young people who escaped deep into Russia in the first days of World War II. She now lives in Birobidzhan.[NOTE]Birobidzhan: capital of the Jewish Autonomous Region, created in the far east in 1928. Zelda married a cousin there and they have two sons.

Berl Glezer in 1937

(enlarge)

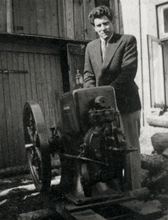

My father was Motl son of Yankel-Meyer [Glezer]. He went to the nearby villages with a box of glass on his shoulders and set panes into windows for the people who needed them. Later he worked as a carpenter, and my brother and I went with him to make windows and doors. Every week on Sunday morning we left to go to work in a village and did not return home until Friday afternoon. My mother was Basha-Rayna. I had two sisters, and a brother who died young in 1927.

When my father died in 1932, I began to make furniture, beds, closets, and chairs. The oak boards were not easy to lift and saw. Later I bought a partly mechanized lift with a motor powerful enough to lift the boards. I expanded my enterprise to include four or five workers. They would usually work until late in the evening because we had so many orders. My destiny is connected to this. There is a lot to say about it. I will write it in a special notebook.

Uncle Pesach, one of my father's brothers, lived near our house. He had two sons, Berke and Yankele, who were yeshiva students. [the house of Pesach Glezer in 2018]

On the left, quite a bit farther along New Street, lived Moyshe-Itze [Reznikovich] the kosher butcher with his daughter Sora-Tzipa, who married Nachman Voskoboynik, an ordained rabbi. Later he became a kosher butcher too. Sora-Tzipa had two sons and a daughter called Nechomele. All of them, including the children, were Zionists. [Read more about the Voskoboynik family.]

Across from them lived Mina, a sister of Yoshke Saltuper. Mina was a very smart woman, but she would very often take leave of her senses. She married Mote Pekl, who played the clarinet. But he could not live with Mina. [Read an anecdote about Mina Saltuper and a report of her death.]

On the corner of Heyfisher and New Streets lived Zalman Shimen-Bunes [Berk] and his wife Chaya-Feyga. She was the bobe [grandma] of the shtetl. When the women of the shtetl were ready to give birth they called for her. She also applied cupping glasses to draw blood to the skin (a traditional remedy) and gave enemas. They had seven daughters and four sons. The daughter Sorka was not right mentally. Libka, Freydka and Risha went to Canada.

Much farther along New Street, near the Hasidic synagogue, lived Ortzik [Glezer] son of Mote. His wife's name was Buna-Gitl [née Berk]. They had four sons and three daughters. One of the youngest, Dveyrele, was a very pretty girl. When she was still very young, a bachelor who came from Russia fell in love with her. They married and left. Now she is in Israel.

On the other side of the tarred little bridge over the ditch lived Binyomin the tailor. His surname was Krasovsky. His wife Feyga was a daughter of Chava-Ester [Solomon]. They had six daughters and one son. The son was a lawyer who worked in Kovno. Many years ago Chayka went to Palestine, and the oldest, Nechoma, went to Brazil to marry Bentzke son of Leyzer [Karpov]. Rivka died in Vilna while still young. The rest of the sisters, Sorka, Sheynka and Beyla-Rochka, are in Israel.

Two young teachers—Motke-Leybe the shammes, who was one of my cousins, and Yisrolkele son of Shimen—worked for a long time in the shop of Binyomin [Krasovsky] the tailor. When a coat or vest needed to be cut, Binyomin didn't show them but did the cutting himself so that they wouldn't see how he did it. Motke went to Africa and Yisrolkele to Palestine. That is what our land Israel was called then.

In the other half of Binyomin's house lived Leybe [Shepshelevich] the shammes and his wife Chana-Basha [née Glezer], my aunt, who was a sister of my father. They had five sons and three daughters. As soon as the children reached the age of 15 they were sent to Riga to earn their bread on their own. They were capable children and in a very short time each one learned to do what had to be done.

Shimen, son of Leybe [Shepshelevich] and of my aunt Chana-Basha, became a hatmaker. He fought In World War I and was killed in 1914. His oldest son, Leyzer, was a revolutionary in 1905 and had to escape to America. Hirshl and Moyshe-Itzik became tailors, while Motke and Marentka were still very young in those years. The older daughter Nechka became a hairdresser, and Sorka studied home economics.

When Hirshl and Moyshe-Itzik sons of Leybe [Shepshelevich] came home to visit their parents for the holidays, the shtetl youth would gather at their house, sing and dance, play games, and play “forfeits.” Afterward they would buy the forfeits and talk about how the young people in Riga got together to have fun. Motke and Marentka, still children, would crawl up on the oven and watch everything.[NOTE]The oven was built into the wall with a sleeping area on top. I still remember the little song we sang in those days. We clapped our hands and sang it together. Trashkun youth lit a spark that inspired the search for a more beautiful life.

| Listen, dear rabbi, To what I will tell you. When I was in Riga I saw a tall steeple On a synagogue That looks like a church! |

Everyone sees it And knows all about it. Everything there is upside-down. To mark the end of Shabbos They let the candle burn for hours.[NOTE]The Jewish custom is to extinguish the havdalah candle immediately after the last blessing is said. |

Bathhouse Street [Birutės gatvė] (map) began in back of the house shared by the families of Binyomin [Krasovsky] the tailor and Leybe [Glezer] the shammes. The first house on the street belonged to Shimen son of Mote, whose family was poor and struggling. They had two daughters and three sons. Every year at Pesach the communal baking of matzo for the entire shtetl was done at Shimen's house.

The next house belonged to Moyshe the flaxmaker, who had a daughter who was not normal,[NOTE]"not normal": Yiddish euphemism for mentally handicapped but Reb Shneyer arranged a marriage for her with a Jew who also was not normal, named Leyzer.

Meir the bricklayer lived behind Moyshe's house and Rabbi Shmukler lived still farther back, beyond the synagogue. Rabbi Shmukler was also the bookkeeper of the folksbank. Nearby was a well with water for the taking by everyone who lived on Bathhouse Street.

Abba Kikhel, a turner [one who works on a lathe], lived in the next house. He made very nice pipes and smoking mouthpieces from cattle horns, and took them to Riga to sell.

Rachmilke [Gordon], one of the sons of Borech the tough guy, lived in the same house as Abba Kikhel. Rachmilke was a painter. While he was still a bachelor, he deceived his girlfriend, Yudiska daughter of Gitele. He went around with her for a long time, but he didn't want to marry her because she was very poor.

Next on the street lived Ovadya Leyzer [Kreytzekovich] the shoemaker. Just before the war he and his wife Chaya and little son went from house to house in nearby shtetls asking for donations so he could give his daughter a big dowry.

A page from Berl Glezer's memoir

Borech [Gordon] the tough guy lived with his second wife in the last house on Bathhouse Street. In earlier years he had been very rich. During World War I Borech had a butcher shop and he lived in the house of Bertzik [Yuzent] the bricklayer while Bertzik was away in Russia.[NOTE]Most Jewish families in Lithuania were forcibly resettled in the east during World War I.

Bertzik's son Nosn [Yuzent] fell in love with my sister Dveyrl, so he didn't leave with his parents [during World War I]. He went with our family and later in Russia they got married. A little daughter was born to them there. They came back in 1919.

To get to the bathhouse you crossed the ditch on a footbridge. Inside, on the left, a large brick oven stood in a hallway and held an iron kettle for heating water; this was the place for heating stones. On the right was a brick mikvah [ritual purification bath] and three small steps with a hand railing leading up to the door that opened into the washing room. Extending from the washing room, a rope for hanging laundry stretched the length of the bathhouse. Four steps inside the washing room led up to a platform from which buckets of cold water were poured over the hot stones, creating big clouds of steam. The bather then flogged himself front and back with a broom made of twigs.

Many Jews who were elderly when I was young had lived in our shtetl for many years, but it is hard for me to remember their names and the houses where they lived. Now while writing I realize that I forgot to mention a very nice family that came to Trashkun from Vilna after World War I. They were very poor and lived in the old house where the post office is now. In those years they had no beds for their four young children, so the parents took the drawers out of the dresser and used them as beds for the children.

Way of Life

Before World War I the Trashkuner Jews lived in the spirit of their upbringing. Starting when they were still children in cheder, the rabbi told them never to forget what they were learning: that there is a God in the world who chose the Jewish people from all peoples, and that nothing in the world happens if God does not wish it. Occasionally a person would ask why something was happening, to which the rabbi replied that one may not ask such questions. It is as it must be. In those years many Jewish families lived fairly well, but there were just as many families where poverty was seen and felt. To believe that was the will of the Master of the Universe made it easier for the poor families to survive hard times.

Among the Jewish townspeople in the shtetl, in addition to merchants and shop owners, were craftsmen, shoemakers, tailors, bricklayers, carpenters, coachmen, and a smith. Many of them ran to the nearby village before dawn to buy things from the farmers to sell in Trashkun—eggs or a bundle of pig bristles or a calf or sheep hide. Even so, the money earned in this way was often not enough to cover expenses. In those days few people remained in Trashkun. The ones who left and found jobs in America wrote yearning letters about di alte heym, the old country, and sent checks for ten or fifteen dollars to make the holidays easier.

Continue to Part II ▶