Escape from Trashkun in 1941

by Shmuel Kovnovich (1908-1989)

Translated from Yiddish by Sonia Kovnovich Mandel

✷ See also • Kovnovich family

• Interview with Shmuel and Hasia Kovnovich

Shmuel Kovnovich (1928)

(click for full view)

On 25 June 1941, I left my native town of Trashkun (Troškūnai), Lithuania. I almost did not get out, since Vilna (Vilnius), Kovno (Kaunas) and almost the whole of Lithuania were already under German occupation. Why did I leave? I find this very difficult to explain, except for the will to live and not to get caught in the claws of the Hitlerist-Lithuanian trash.

I left with my father, Shloyme son of Getzl (“Shloyme Getzl’s” is how people were called in the shtetls), and with a whole group of people following behind a horse and a wagon where we had placed belongings from home (sheets, blankets, clothes, food). The following are the names of people who left Trashkun with us: Berl son of Motl [Berl Glezer] (a cousin)[NOTE]Shmuel Kovnovich and Berl Glezer were second cousins. and his wife Fridka; four young women (Muska [Kushner], Chanka [Kushner], Beyla-Rochka [Krasovsky], Rivka [Krasovsky]); Moyshe-Fayvke [Pevzner], who worked for Binyomin [Krasovsky] the tailor; Lurie and Obert,[NOTE]Possibly Itzik Lurie, born in Raguva in 1921, and Lev Obert, born in Kalvarye in 1924. whom I met again later in a kolkhoz (collective farm) in Chkalovskaya Oblast[NOTE]now Orenburg Oblast and with whom I traveled to Uzbekistan.

We walked at a fast pace, hurrying to keep up with the horses and wagons, while many other Jewish people who were fleeing the fascists joined us on the way. One of the women from our town by the name of Dobra, wife of Shloyme [Kushner, not Kovnovich], while pushing her daughter’s child, her grandchild, in a carriage (I don’t quite remember whether it was a boy or a girl), was crying and kept repeating that “Whenever a Jew is born, a blanket of darkness and misfortune descends upon this world,” and other words of that sort, while the daughter’s husband, Yisroelke son of Bashra (alav hashalom, may he rest in peace), supported her by the arm.

We walked for miles. We had come a long way from Trashkun, almost halfway to Aniksht (Anykščiai), one of the larger cities of Lithuania, when a Lithuanian peasant approached us, asking where we were going. I answered in Lithuanian that we were fleeing the Germans. I remember clearly that it was a Wednesday, because it was market day in Aniksht and all the peasants from the neighboring towns brought their produce to this big market. The Lithuanian peasant laughed at us, saying we had no chance because the Germans were already everywhere.

I do not quite remember at which train station we were before Aniksht, but a small train just happened to stop there and some of us managed to climb onto a car. As I looked outside the window, I saw peasants with their horses and wagons full of produce coming along the main road to Aniksht. I also saw my father standing by the side of the road, looking sadly at me; he had not climbed onto the train. While we looked at each other, I remembered that he had complained to me on the way that his feet hurt and that it was very hard to walk any farther. I tried to encourage him, saying that after we passed Aniksht we would rest.

That was the last time I saw my father. I spoke to him again only after the war, in the attic where we were living in Vilnius. There he appeared to me in a dream. He walked in as if he were alive, wearing the same clothes that he had worn when he left Trashkun. He said, “Why did we have to suffer so much?!”

For some time after that, I continued looking out the window, watching poor, tired Jews walking behind the train. I think Chaimke son of Leyzer was with me in the train. Also from Trashkun were Ruvke son of Fishl and his sister Chanka, a beautiful, dark-haired, oriental-looking young woman. Looking at these people who had left their homes and sometimes their loved ones behind, fearing death, I felt my own and their deep sorrow, the loneliness and homelessness that enveloped us all. I knew that a horrible death awaited my father somewhere. These feelings contrasted strongly with the beautiful landscape of the surrounding countryside. It was summer. All around us were woods, forests, meadows. Everything was brilliantly green. I thought to myself: why, in such a beautiful part of the world, is there no room for a handful of Jews? I remember, as we passed by a town near Deroshevitz, the head rabbi cried out the following words as he and his congregation were being led away by the fascists: “Jews! We led a life of lies! The heavens are empty: there is no God!"

A page from Shmuel Kovnovich's manuscript

(enlarge)

The little train onto which some of us were lucky enough to climb stopped at Utyan (Utena) station on the way to Aniksht. There, an incident occurred that almost cost us our lives. While the train was standing, I noticed that a few shaulists, Lithuanian Nazi collaborators, were looking into the window of our car. One of them kicked open the door and aimed his gun directly at the people. Inside were only Jews—men, women and children from Trashkun and other places. I shouted out at him, “Nešauk!” (Don’t shoot!) as I quickly slammed the door on him. Then, crouching down, I managed to fix the latch on the door to keep him from entering. Later, Rivka daughter of Binyomin [Kraskovsky], who was with us on the train, came over to me and said in amazement, “Where did you find in yourself such courage and daring?” But the Lithuanian Nazi collaborators did not give up so easily. They ran to the side of the car and began shooting through the door and through the window. At that moment, two young Red Army soldiers from the adjacent car jumped out of the window, guns at the ready, and chased off the shaulists.

We went as far as Švenčionėliai (in Yiddish we called it Svintsyanke[NOTE]“Little Svintsyan”) on this train. It went no further. We got off and walked to a bes-midrash, a Jewish school. The Jews of this shtetl were too scared to let us into their homes—they feared reprisals. In the bes-midrash we found mostly elderly women but also some young women who had fled Aniksht. The young women told us about atrocities they had seen as they fled. The shaulists found them on the way and shot their husbands, men and young boys, in front of their eyes. To this day I can hear the crying and heart-rending screams of these women.

In the same area outside of Aniksht, apparently, Elke son of Shloyme [Kushner] was shot by his Lithuanian friend Paškevičius, who had been employed as a policeman under the Soviet regime before the German occupation. They left Trashkun together on bicycles, and according to Berke son of Motl [Berl Glezer], who survived the war, they encountered Lithuanian Nazi collaborators on the way. The collaborators ordered Paškevičius, a pro-Soviet Lithuanian, to shoot his friend (may God avenge their blood!) in order to save his own life.

While we were in the bes-midrash, the caretaker of the synagogue came in and, with a trembling voice, told us that the German administration had posted notices all over the town, warning that if any of the town’s Jews were found harboring in their homes Jewish runaways from other places, they would be shot on the spot.

I said to Berke, “Let’s go to Svintsyan” (Švenčionys), a city that had previously belonged to Poland. The women from Aniksht tried to dissuade us, saying that they had heard from a woman who had escaped about murderous acts against Jews who had tried to escape from there. All the same, we decided to go. A few kilometers from Svintsyanke, at the main post office, we came face-to-face with two Lithuanian soldiers who looked like deserters. They aimed their rifles right at us, ordering us to place all of our possessions on the ground. It was very lucky for us that at that moment a Soviet truck with Red Army soldiers who were retreating from occupied territories drove up beside us. We seized the moment. Binyomin the tailor’s assistant, Lurie (I have forgotten his first name; his mother married Baruch after Baruch’s wife, nicknamed “Basha the frog,” died) and I dashed into the cornfield by the side of the road. We crawled on our bellies through the field and finally came out in a place not far from Svintsyan. There we met up again with Berke and the rest of the Trashkuner Jewish people with whom we had been traveling.

There we entered another bes-midrash, but the situation was not so frightening. The population of this town was mixed: Poles and Byelorussians. It was already dusk, time for ma'ariv, the evening prayer. The bes-midrash was full of Jews. They gave us something to eat and drink. I remember that one of the men who gave us food blessed me and wished me good luck. I lay down on one of the bunks but I could not shut an eye, even though I was extremely tired. At the crack of dawn, we noticed outside a unit of Red Army soldiers in retreat. I ran out to ask their commander, who was marching beside his unit, if we could join them on their march. He answered, “Poidiomte (Let’s go).” We suddenly sprang to life. We were exhilarated!

While walking, he told me that many Jewish women along the way had asked the soldiers to accompany them as they fled their shtetls. But he had refused because the women would have held them back. Then he said he had seen our group before, that we were young and energetic, and so he allowed us to join them.

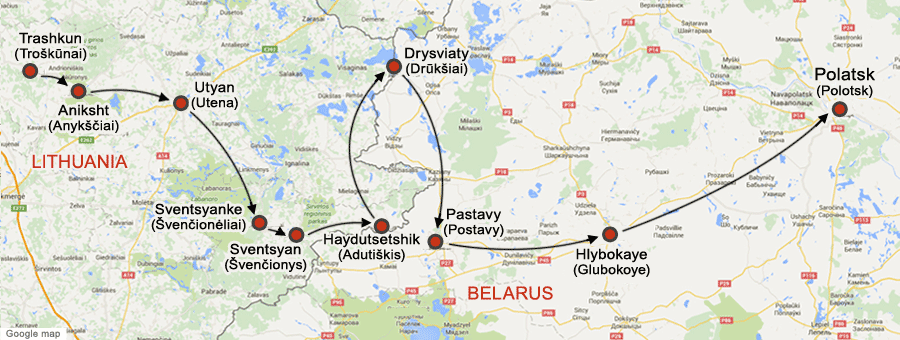

We passed many shtetls on our way: Haydutsetshik (Adutiškis), Drysviaty (Drūkšiai), Pastavy (Postavy), Hlybokaye (Glubokoye), and later Polatsk (Polotsk). Before entering each of these towns, the Russian commander would send ahead a couple of soldiers dressed in civilian clothes to check the situation, whether or not the town had been occupied by the Germans. Sometimes he sent me with his soldiers, since I was able to communicate in Polish and in Lithuanian.

The escape route of Shmuel Kovnovich in the summer of 1941, from Trashkun to Polatsk.

On one of our reconnaissance missions we crossed a bridge. The captain noticed a Lithuanian soldier under the bridge. He looked like a deserter. The captain led him aside, searched him and found a bell. The Lithuanian soldier made the excuse that he had taken sick and so had fallen behind his unit. I translated, since he spoke only Lithuanian. I saw the soldier turn chalk white. Never before had I seen such paleness on a human. It was the expression of a man facing death and afraid to die! The captain took him behind the bushes. A shot rang out, and the captain emerged alone from the bushes.

We greatly valued our time spent with the Soviet unit. We felt more secure. Moyshe-Fayvke [Pevzner] wanted very much to learn how to shoot a rifle, and one of the soldiers obliged. We were taught how to dig a prival, a deep trench in the ground under a big, thick tree. That is where we would rest for the night. Sometimes, before falling asleep, the young women in our group would begin to feel homesick and would start crying, thinking about the loved ones they had left behind and the fate that awaited them. I felt their pain. I did not cry out loud, but my heart was aching. I was thinking about my father, my uncle Moshe-Itzik, Ita. I often asked myself why I left them behind. Why could we not have left together? At one point, the Soviet captain turned towards the lamenting young women and asked, “Are you already sewing shrouds for your families?” He used the Yiddish word for shrouds, takhrikhim. I asked how he knew that word. He said he was Jewish.

For the first time, I saw people, including myself, walk like horses, trying to ignore their pain and total exhaustion, although they were on the verge of collapse. In addition, I had very painful blisters on my feet. We arrived at Glubokoye in the evening. On our arrival, we noticed a large crowd gathered in the square. They were all Jews, including women with small children, hungry, exhausted, crying and screaming. Besides that, the heavens opened the tap and a heavy rain began. Luckily it stopped very soon. We were refreshed, but very wet.

Then, suddenly a fast-moving truck, apparently belonging to the NKVD (Soviet political police), was heading right for the Jews in the square. But our Red Army commander immediately became suspicious. First of all, the faces in the truck did not look Russian: the cheeks were fat—those people had not known any shortage of food. The captain’s reflexes were quick. He shot the tires of one of the trucks, forcing it to stop. Then he and a couple of his soldiers went over, their revolvers pointing at the men in the truck, and ordered them out. They searched them from head to toe and questioned them. Not all of these phony NKVD people spoke Russian. Normally, the NKVD units retreated before the army units. That is why our commander was suspicious. He and his soldiers led the fascists away from the square. A series of shots rang out from there.

It was a Saturday. The tailor (I forgot his first name but his surname was Lurie), Moyshe-Fayvke, myself and many other people crossed the town. I remember clearly, it was the fourth day of our difficult and danger-filled march. We knocked on a door of one of the Jewish houses, and they let us in. In the house there was a Sabbath atmosphere. Candles were shining on the table covered with a white tablecloth. The hostess was crying, pointing to her young daughter, a beautiful blond girl. She cried out, “Oy-vey! What will become of us?” Her husband had been drafted into the army, leaving her and her daughter to manage alone.

After our visit, we walked towards the old border of West Belarus before it had been annexed by the Soviets. There I again met my cousin Berke son of Motl and his wife Fridka, from whom I had been separated along the way. It was not a very dense forest. We built a shelter from twigs and branches and stayed there for three full days. On the third day, the tailor Lurie, a young man from Vilnius who used to live on Kalvariskaya Street, and myself left our hiding place to look for food.

We encountered Soviet border guards on their horses as we approached the nearest village. In the village, we got something to eat and potatoes to take with us. But the border guards would not let us return to our hiding place. So we continued forward on our way to Polatsk, but now without the Red Army soldiers, from whom we had already been separated in Glubokoye. On our way to Polatsk we came to a kolkhoz, where we hoped to stop for the night because it was getting dark. But the peasants refused our request. However, a Byelorussian peasant let us stay in a barn. As she spread fresh hay, she said in her language, “Niech menia Hitler zabiye, zahodite rebiata” (Let Hitler kill me. Come on in, lads). We were so tired, almost falling off our feet. We lay down at once and fell asleep. I was awakened by Lurie pulling on my sleeve. “Shmulke, wake up! There’s food!” The Byelorussian peasant led us to her cottage and placed before us on the table freshly boiled potatoes “in their jackets” and a pitcher of milk. We hungrily poured the milk into cups and drank it with the potatoes. In all my life I have never had a more delicious meal!

❖

☛ See also: In a 1965 oral history interview, Shmuel Kovnovich and his wife Hasia recount

their wartime experiences in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.

PHOTOS • Shmuel Kovnovich in 1928

• Shmuel Kovnovich with his parents (~1928)

• Shmuel and his brother Avrom with other Zionist pioneers in Trashkun (1930)

• Shmuel Kovnovich with Itzhak Konkurovich in Vilnius (1957)

• Shmuel Kovnovich with Itzhak Konkurovich in Pajuoste (1957)

• Shmuel Kovnovich with other survivers from Trashkun in Israel (1987)

Photos below: Trashkuner survivors gather at the memorial at Pajuostė, near Panevėžys, where the Jews of Trashkun were murdered in 1941. These photos were sent to Shmuel Kovnovich by other survivors.

Pajuostė 1959 (click to enlarge and see key)

Pajuostė 1961 (click to enlarge and see key)