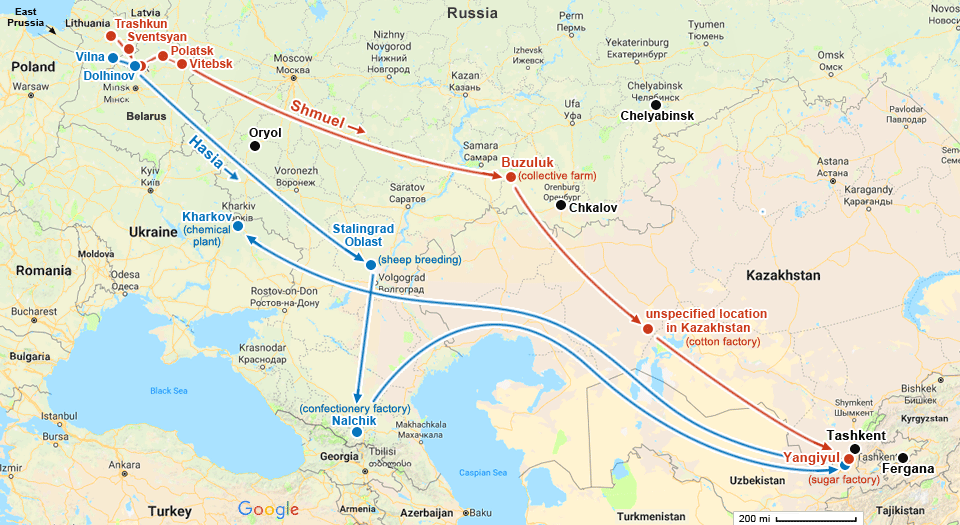

Shmuel and Hasia Kovnovich

Interviewed by Dov Levin

✷ See also • Escape from Trashkun in 1941 by Shmuel Kovnovich

• Kovnovich family

In 1965, the scholar and historian Dov Levin recorded an oral history interview with Shmuel Kovnovich (Kovnovitz) and his wife Hasia (née Dlot) in their apartment in Jerusalem. The interview was conducted in Yiddish (see below). This English transcript, translated by Bella Bryks-Klein, has been edited and condensed.

I N T E R V I E W

Dov Levin • Shmuel Kovnovich • Hasia (Dlot) Kovnovich

Dov Levin

(click for full view)

Dov: Mr. Kovnovich, you’re a Lithuanian from the shtetl Trashkun. What did you do when the war broke out, you and the people of your shtetl?

Shmuel: What did we do? We tried to decide whether or not to leave. Some took the position that “the devil is not as terrible as he is depicted.”[NOTE]a Yiddish folk saying After all, there were those who lived through the First World War.

Dov: The German occupation?

Shmuel: Yes. People thought they could exist somehow. No one could even imagine a concept like general extermination.

Dov: How did you decide to flee?

Shmuel: I was a barber, and I would listen to people. I was an attentive listener by nature, and through my customers I felt the mood of the Lithuanian population. People used to come to me for a haircut, and I sensed a frightening atmosphere.

Dov: Did you have many Lithuanian customers?

Shmuel: Yes, mostly Lithuanians. Even before the war broke out, there were officers from the Lithuanian army who came to me. This was in the winter of 1941. It was already the German-Polish war, and Hitler was occupying one country after another. The Soviets were in power at the time. The Red Army had invaded in 1940. I heard a Lithuanian officer say, “You think it’s going to stay like this? The Germans think of the Baltic countries as their colonies, and you’ll see what will happen in the spring.”

Dov: Who was this person?

Shmuel: A former officer in the Lithuanian army.

Dov: Was he a civilian?

Shmuel: Yes. It was the Lithuanian army but it had already been integrated into the Soviet army. I understood—not so much through reason, but I just had the feeling—that things would not be good here and that we should get out. Also something happened several days before the war started. Former capitalists were deported, people in right-wing Lithuanian organizations. And there were Jews among the capitalists.

Dov: Also from Trashkun?

Shmuel: Also from Trashkun, yes.

Dov: How many Jews were deported from Trashkun?

Shmuel: Not many, maybe two families.

Dov: What were they, capitalists or zionists?

Shmuel: Neither, one might say, but people thought of them as former zionists. At that time someone came into my barbershop. He actually was a Jew and he even spoke to me in Yiddish. I asked him, “What are you here for?” He said, “We’ve come to kick out the thieves.” I said, “What do you mean, kick them out? And what about us? We stay here?” He said, “There’s nowhere to go. People should fight right here. Stay in Lithuania and fight.”

There were a few who got out and survived.

Dov: Was he a military man?

Shmuel: Yes, from the NKVD.[NOTE]NKVD: Soviet secret police.

Dov: So he was giving you a sign that war was imminent?

Shmuel: Yes. And there were a few who got out and survived. There were the Krasovsky daughters,[NOTE]Sora, Sheyna, Rivka, and Beyla Rocha Krasovsky, daughters of Binyomin and Feyga (Solomon) Krasovsky. now living in Kovno, and Berl Glezer,[NOTE]Berl Glezer, born in 1905, son of Motl Glezer and Basha (Kavalsky) and the Chaimovich brother and sister,[NOTE]Neyach and Sara (Sorka) Chaimovich, son and daughter of Nochum Chaimovich and Feyga (Ades) and the Lurie family. We all left the shtetl.

Dov: So few? Only five or six people from the whole shtetl?

Others went into the woods and perished.

Shmuel: Yes, from the whole shtetl.

Dov: And what about the young people in the shtetl?

Shmuel: Others went into the woods and perished.

Dov: How?

Shmuel: They simply couldn’t hold on, because there was no partisan movement and nowhere to turn. Anyone who saw them would immediately inform on them, and then the Germans would attack them.

Dov: You heard about this later?

Shmuel: I heard it when I came back, in 1946.

Dov: Did they wander around in the woods for a long time?

Shmuel: Not for long.

Dov: Weeks or months?

Shmuel: Maybe a few weeks, not more. Many of them were friendly with peasants and felt that it might be safer in the villages. They went there with their entire families. But there was an order that wherever Jews were found, those hiding them would be held responsible and would be killed along with the Jews.

Dov: From whom did you hear about all this?

Shmuel: I heard about it later, from the Lithuanians.

Trashkun was Judenrein. Not a single Jew was left.

Dov: From non-Jews?

Shmuel: Yes.

Dov: You didn’t find any Jews at all?

Shmuel: Trashkun was Judenrein.[NOTE]Judenrein: German term meaning "cleansed" of Jews. Not a single Jew was left.

Dov: What happened to the Jews who left with you, the ones whose names you mentioned earlier?

Shmuel: There were some young ones. Moyshe-Fayvke Pevzner[NOTE]Moyshe-Fayvke Pevzner, born in Trashkun ~1923, son of Leybe Pevzner and Chana (Solomon) was a young one who joined the Lithuanian Division. Then there was someone we called Henochke, Henochke Zavls.[NOTE]Henoch Martsushky, son of Zavl Martsushky and Freda (Vinik) He was a paratrooper, I was told, and he was killed. He jumped from an airplane and fell into the hands of the Germans.

Henoch Martsushky

Dov: Where did he jump out?

Shmuel: In Lithuania, after it was occupied.

Dov: Is Zavls his family name or his father’s name?

Shmuel: His father’s name.[NOTE]Henoch, son of Zavl I don’t remember his family name.[NOTE]Martsushky

Dov: Are you sure that this Henoch Zavls jumped out of a plane?

Shmuel: Yes, I know for sure. The people I left home with were Lurie[NOTE]Possibly Itzik Lurie, son of Moyshe and Chava, born in Raguva in 1921 and lived in Trashkun. and someone from Kalvarye (Kalvarija) whose surname was Obert.[NOTE]Possibly Lev Obert, son of Shepsel, born in Kalvarye in 1924. Later they were both mobilized in the Lithuanian Division, in 1943, and they were both killed. I was told this by someone from Kalvarye, Obert’s shtetl.

Dov: Was he in Oryol, in the battles there? [NOTE]Oryol: a Russian city occupied by the Wehrmacht on 3 October 1941, and liberated on 5 August 1943, after the Battle of Kursk.

Moyshe-Fayvke Pevzner

Shmuel: Yes, and later they were in East Prussia.[NOTE]East Prussia was immediately to the west of Lithuania, bordered by the Baltic Sea to its north and by Poland to its south and west. (map)

Dov: And the name you mentioned before, Pevzner?

Shmuel: Pevzner was also in the Lithuanian Division.

Dov: Was he killed too?

Shmuel: He was killed when the Lithuanian Division went into battle. And one of my friends, Itzik Konkurovich,[NOTE]Itzik Konkurovich, born in 1912, son of Chaim Sholem Konkurovich and Chaya Sora (Levinson) was also in the Lithuanian Division.

Itzik Konkurovich

Dov: Where was he from?

Shmuel: Also from Trashkun.

Dov: Did he leave with you?

Shmuel: He was in Kovno. He escaped from Kovno. Later [after the war] he was in Vilna.

Dov: Is he still alive?

Shmuel: Yes.

Dov: Do you remember any other names of people from Trashkun who fought in the Lithuanian Division or in other sectors of the Soviet army?

Berl Glezer

Shmuel: No.

Dov: Or in labor battalions?

Shmuel: Berl Glezer, whom I mentioned before, also served in a labor battalion. He was in Siberia.

Dov: Why was he in Siberia?

Shmuel: He went there himself. When he left, it was just a matter of fate that he ended up so far away. [Read Berl Glezer’s account.]

Dov: And what happened to you? You took off on Wednesday?

Shmuel: Yes.

Dov: That’s Wednesday, 25 June 1941.

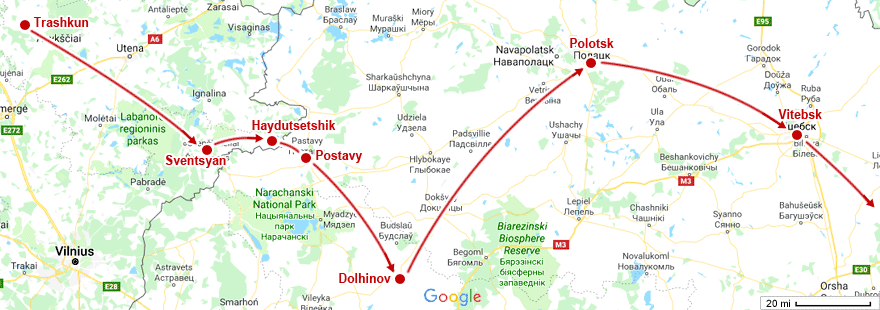

Shmuel: Yes. We got out late. We had already been occupied. But there were some soldiers from the Soviet army who were retreating from the front, who were leaving the front because they had already been defeated. I went with them, starting from Sventsyan (Švenčionys). We went on foot. [Shmuel describes this journey in his written memoir.]

Dov: Was Sventsyan nearby?

Shmuel: From Trashkun to Sventsyan is quite a distance, about 70-80 km. We got to Sventsyan and people told us the road was very dangerous since there were Lithuanian former Shaulists[NOTE]Shaulists: Nazi collaborators who weren’t letting anyone through. Above all, they wouldn’t let through any Jew who wanted to get out. We were lucky that just then a detachment of defeated soldiers was passing through. They were barefoot, no hats, no weapons. Maybe one in ten had a gun. I asked them if we could join them, on behalf of our whole group. I approached them because I knew Russian.

Dov: On behalf of your little group of 5-6 people?

Shmuel: Yes. I asked if we could go along with them. He said in Russian, “You’re welcome to come along with us.” And so we went with them through the towns of Haydutsetshik, Postavy, Dolhinov. Some of these places were off the direct route. The commander would send out a reconnaissance group to see if any paratroopers had landed in the area. The Germans would move in and drop parachutists in places that previously had not been occupied but later were held by the Germans. That’s how Lithuanians got shot, even Lithuanian soldiers. When the war started, parts of the Lithuanian army were sent far from the front so they wouldn’t fall into the hands of the Germans. There were Lithuanian soldiers [pro-German] who stole away from their unit, from their station, and remained behind. They would just hide and shoot from behind whatever there was—a tree, a house—at those who were retreating.

That’s how we proceeded, barefoot and naked and hungry, until we got to Polotsk.

Dov: How did you get across the border? Did they let you cross?

Shmuel: They didn’t let us—that was the issue. For three days we were in a forest at the border and they wouldn’t let us cross. On the third day, I was with Lurie and Obert from Kalvarye, and we went out to look for food. We had taken nothing with us and we were simply dying of hunger. We saw that the peasants nearby were fighting over anything edible. At the same time, we heard airplanes that suddenly appeared overhead and started to bomb the area.

Dov: How did you get through?

Shmuel: We just walked out and somehow crossed the border. They didn’t want to let us through, but—

Dov: What did they tell you?

Shmuel: They said, “This is the border, and you are not Soviet citizens. Turn back.” We said, “Better you shoot us than we get shot by the bandits.” So they let us go, and they gave us directions so that we wouldn’t run into any army positions.

During a bombing one should lie down.

Dov: You said that you went as far as Polotsk?

Shmuel: Yes.

Dov: You reached Polotsk on foot?

Shmuel: All on foot. When we reached Polotsk, the Germans hadn’t gotten there yet. We went to look for a place to sleep because it was already evening. They directed us to a place called (in Russian) “House of the Red Kolkhoz.”[NOTE]kolkhoz: collective farm One of us went in to ask if there was a place to wash our clothes. We were filthy. Our last shirt was as black as the earth. So we gave someone our underwear to wash.

At two o’clock in the morning, before dawn, bombs started falling. We ran out into the yard and lay down, following the instructions that during a bombing one should lie down. If there’s no better place, then at least lie down. A bomb landed not far from us and covered us with earth. There were about 20 Messerschmidts. When the bombing stopped, we couldn’t go back inside because it was on fire. We grabbed the only clothes we still had and left. We walked through the town. Wounded soldiers were running away, and others lay dead on the ground. We passed by a store that wasn’t damaged and went inside. No one was there. It hadn’t been bombed. We took some loaves of bread and left town.

Dov: When were you mobilized?

Shmuel: In the beginning of 1942.

Dov: Where were you until then? In what places?

Shmuel: We walked to Vitebsk. Then there was an echelon [long train] of evacuees, Jews who had left Vitebsk. They were factory workers, tailors. We joined this echelon of evacuees.

Dov: Until where?

Shmuel: There was an “evacuee point” where they would assign people where they should go. And so we went to this evacuee point and they gave us the choice of either Chkalov [now Orenburg] or Chelyabinsk.

Dov: In the Ural region?

Shmuel: Yes, mostly in the Ural region. We didn’t know how to choose, but we requested Chkalov. Not far from Chkalov, we sat and waited at the Buzuluk station—not in a railroad car, because the railroad cars were full of soldiers who had evacuated. We would lie on the platforms near the railroad cars. We would sit there in the evenings and talk to each other in Yiddish. Someone from the NKVD heard us and thought we were speaking German. He told us to follow him.

Dov: I’ll tell you, this happened to almost every Jew; people thought they were speaking German. For how long were you arrested?

Someone from the NKVD heard us and thought we were speaking German.

Shmuel: They held me for 24 hours.

Dov: Where did you finally settle?

Shmuel: We were told, “Why do you need to go to Chkalov? There are good collective farms right here. We’ll send you to one of those.”

Dov: Who told you this?

Shmuel: An NKVD officer. We still had Lithuanian papers on us. He looked through them but he—

Dov: He couldn’t read them?

Shmuel: He couldn’t read them, but he did realize that we were not spies. He told us, “You’ll go to a kolkhoz[NOTE]kolkhoz: collective farm for the time being. Otherwise they will mobilize you into the army. You’ll work there.” And that’s how we got to the collective farm.

Dov: Who is “we”?

Shmuel: Lurie and Obert and myself.

Dov: Just the three of you?

Shmuel: The others who left Trashkun with us got lost at the border. I didn’t see them again until after the war. In 1946 in Vilna we met Glezer, Konkurovich and Chaimovich.

Dov: Where had Chaimovich been?

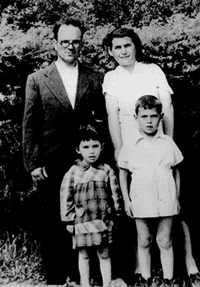

Neyach Chaimovich and his sister [Sara]

Shmuel: Chaimovich was in various places, he and his sister.

Dov: Had he also been in the army?

Shmuel: He was still young, not more than 14, so he wasn’t mobilized into the army. He was still a child.

[Note: The age difference between Shmuel Kovnovich and Neyach Chaimovich can be seen in this photo, taken in the late 1930s.]

Dov: How long were you in the kolkhoz?

Shmuel: We arrived at the kolkohz on 3 August 1941, and we were there until winter. It was about four months, not longer—August, September, October, November. It got cold. We had no clothes to wear. We just walked around naked and barefoot. We said to the head of the kolkhoz, “What will become of us here?” He replied, “Yes, you’re right, it will be very hard for you. It’s a harsh winter and you don’t have clothes or anything else.” Afterwards we found out that such things were provided for the evacuees, but we didn’t see that.

Dov: What did he tell you to do?

Shmuel: He said we should go to a place where there is no winter, to Central Asia, to Tashkent.

Dov: So you went?

Shmuel: Yes. There was a Jewish family that was evacuated from Belarus, it seems to me. We went with them.

Dov: Where exactly did you go?

Shmuel: We had wanted to go to Fergana[NOTE]Fergana is a city in eastern Uzbekistan, about 240 km (~150 miles) southeast of Tashkent. but we didn’t get there. A Jew told us, “Why go to Fergana?” This was already in Kazakhstan. “There’s a cotton factory at the station,” he said, “and there are other Lithuanians there.” So that’s where we went. It’s true, there were other Lithuanian young people there, but there was terrible hunger. We had nothing to eat and nothing to wear, and we were paid wages according to what the prices were in good times, when you could get a kilogram of bread for a ruble. But now a kilogram of bread cost 100 rubles. There were times when I ate garbage, the stuff they fed the oxen.

There were times when I ate garbage, the stuff they fed the oxen.

Hasia: Cattle feed.

Shmuel: Cattle feed, yes.

Dov: In short, this was not a good thing. I understand.

Shmuel: When we got there, in the beginning of 1942, we registered in the village and they also registered us with the military. I received a notice to appear at the command, and they admitted us. There was a reserve regiment there, an anti-aircraft regiment. I was falling off my feet from hunger. They sent me off to a hospital committee, where they told me I would not be sent to the front. They sent me to work in a factory where cotton padding was cleaned. It was a labor battalion.

Dov: And all three of you went to work in the factory?

Shmuel: Yes.

Dov: Meanwhile, did you hear that there was a Lithuanian Division?

Shmuel: No, at that time we hadn’t heard about it.

Dov: How long were you in the labor battalion?

Shmuel: Exactly one year, until 1943.

Dov: And that entire time, you heard nothing about their taking Lithuanian Jews into the Lithuanian Division?

Shmuel: We did hear later. In 1943, my two friends were mobilized again and sent off to the Lithuanian Division.

Dov: Did you correspond with them?

Shmuel: No, I had no news of them. It was not a regular life then. Maybe they wrote to me, but I didn’t stay in one place.

Dov: Did you want to join the division too?

Shmuel: Of course I wanted to.

Dov: Why? Was it better there?

Shmuel: People said it was much better. I asked them to send me there, but they said it wasn’t necessary, that they would summon me if needed.

Dov: The other people there were locals?

Shmuel: Yes, most of them were from Uzbekistan.

Dov: Were they able to get by?

Shmuel: They managed. They received support from home.

Dov: You didn’t feel it was good for you there?

Shmuel: It was very bad.

Dov: How did you get out?

Shmuel: I simply went to another place. A sugar factory was built in Yangiyul.[NOTE]Yangiyul: a city in Uzbekistan near Tashkent I told our supervisor that I couldn’t last there any longer and that I would do better in Yangiyul. I was starving.

Dov: You knew nothing about what was happening back home?

Shmuel: I knew nothing.

I didn’t know anything. I was out there in Yangiyul.

Dov: Did you know what was happening in Moscow?

Shmuel: I didn’t know anything. I was out there in Yangiyul.

Dov: How long were you in the sugar factory?

Shmuel: I was there until I came back in 1946, after the war ended.

Dov: Was it any better in the sugar factory?

Shmuel: It was a little better because we would get sugar cane, and we would bake it and eat it.

Dov: Would they also give you real sugar?

Shmuel: We didn’t see real sugar with our own eyes, but we used to illegally—

You had to learn how to steal.

Dov: You would manage.

Shmuel: We would manage.

Hasia: You had to learn to be a thief there. You had to learn how to steal. I was also in that sugar factory.

– H a s i a –

Dov: Please, tell us about it.

Hasia: I don’t remember everything. I remember that I met him at the sugar factory.

Dov: What did you do in the sugar factory?

Hasia: I was the manager of a large department in a warehouse where there were barrels of pickles, barrels of wine. There were lots of good things there.

Dov: And you are from Vilna?

Hasia: I’m from the vicinity of Vilna.

I already escaped in 1939, when the war started with Poland.

Dov: Did you escape too?

Hasia: I already escaped in 1939, when the war started with Poland. I went to Russia, and my parents and my whole family were murdered.

Dov: You left with the Soviets?

Hasia: Yes, I traveled with them. Those who wanted to enlist could join them. I was in Vilna. I had a girlfriend there. I had gone to visit my brother in Dolhinov, and my girlfriend wrote to me that she was enlisting. She had nothing to do in Vilna, no job, nothing.

Dov: There were no jobs in Vilna?

Hasia: No. There was unrest, and there were no jobs. We had worked together in a confectionery factory in Vilna.

Dov: So you left with the Soviets and stayed there?

Hasia: I enlisted and we were sent to the Stalingrad Oblast.[NOTE]now Volgograd Oblast

Dov: To a kolkhoz?

Hasia: To a plemkhoz. It was a farm for breeding sheep.

Dov: Did many Jews leave Vilna at that time?

Hasia: Many people left. Some went here and some went there.

Dov: Did some of the people who left go into the military?

Hasia: Yes!

Dov: Later, did you ever come across any people who had enlisted?

Hasia: I never saw them again.

Dov: So how do you know?

Hasia: I heard from others. I was with my girlfriend in Stalingrad Oblast for about a year or year and a half. This was in 1940. I told my girlfriend that I didn’t want to stay there. It was lonely. I wanted to be in a city. I wanted to be among people, not on an isolated sheep farm. So I left her and went to Nalchik in the Caucasus.[NOTE]Nalchik: the capital city of the Kabardino-Balkar Republic, located in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains In 1941, when the war started, I had been there one year. That year in Nalchik, I also worked in a confectionery factory.

Whoever can save himself should save himself.

Dov: When did you arrive at the sugar factory?

Hasia: Then the director told us that things were looking grim in Nalchik. “Whoever can save himself should save himself. Are you Jewish?” he asked. I said, “Yes, I’m Jewish.” He said, “Then I will give you documents. You can go wherever you want.” That's when I went to Yangiyul, where I met Shmuel.

Dov: What was Yangiyul? Was it a military factory? You had not been mobilized, so how was it that they hired you there at the factory?

Hasia: Simply because of Shmuel’s influence.

Shmuel: We didn't have enough workers.

Hasia: Then in 1943, I left the factory and I was mobilized. They took me into the Labor Army and they sent me to Kharkov. They had just liberated Kharkov from the Germans. They sent me to a chemical plant. I have here my work-record book, which shows that I was mobilized.

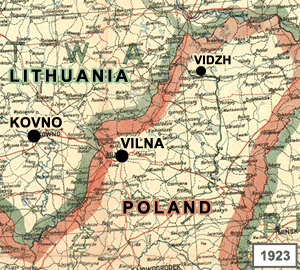

Dov: It states here that you are from Vilna. Were you born in Vilna?

Vilna belonged to Poland in the interwar period.

(view larger region)

Hasia: I wasn’t born in Vilna but I lived there.

Dov: But were you born in Lithuania?

Hasia: Not Lithuania. Poland. But Vilna was in Poland.[NOTE]The Vilnius region of Lithuania belonged to Poland between the two World Wars. Vidzh,[NOTE]Vidzh (Yiddish), Vidzy (Belarusian), Widze (Polish) also belonged to Poland between the wars. It is now in Belarus. where I was born, was also in Poland. Shmuel is from Lithuania but I’m not.

Dov: Now, what about your husband? Why didn’t they take him?

Hasia: He got a contusion when the bombs fell near him in Polotsk.

Dov: That’s why he wasn’t taken into the army?

Hasia: Of course. He had the head injury and he also had ulcers—not one but two. That’s why they didn’t take him. He is still not well.

Dov: Was he considered an invalid?

Hasia: He was considered a handicapped person.

Dov: Was he recognized as wounded in war or just a sick person?

Shmuel: A labor invalid.

Hasia: He also has a booklet, a Russian and a Polish booklet.

Dov: I would be interested to see them.

Hasia: This is the work-record book they gave me when I left the chemical plant.

Dov: “Hasia Peysachovna,[NOTE]Hasia, daughter of Peysach. Hasia's surname was Dlot before she married. confectioner.”

Hasia: Yes.

Dov: And this is your document, Mr. Kovnovich: “Kovnovich, Samuel Shlomovich,[NOTE]Samuel (Shmuel) Kovnovich, son of Shlomo. 9.9% disabled.” But it doesn’t say what caused your disability. It does say that you should get a war pension. I’m interested to know why they didn’t take you into the military, and why they took you to the factory instead. Was it considered semi-military?

Shmuel: Semi-military. Those who were not capable of going to the front were sent to a labor battalion.

Hasia: Labor Army.

Dov: Did you go before a military committee?

Shmuel: Yes. A committee came to the factory from time to time, and those who were fit were taken into the ranks of the Soviet army and sent to the front. They didn’t send me to the front. They couldn’t take me because of my health condition.

Dov: And you got less than the soldiers?

Shmuel: We got less.

Hasia: People used to steal his bread coupons.

Dov: How do you know this?

Hasia: We already knew each other. This was 1943, before I went to the Caucasus and was mobilized.

Dov: He stayed there by himself, and you met again in Vilna after the war?

Hasia: Yes, in 1946.

Dov: [to Shmuel] And because of your injury, your friends were taken into the Lithuanian Division and you were not.

Shmuel: That’s right.

Dov: Were any of your friends in the same situation as you were? Other Lithuanians?

Shmuel: No, I don’t believe I heard of any because most of the people who left with me were young. Berl Glezer was in the same situation, but he wasn’t with us. They didn’t send him to the front, and he spent the war years in Siberia, not where I was.

Dov: How were you demobilized?

Shmuel Kovnovich

in 1957

Shmuel: I was simply released after the war.

Dov: After the 8th of May?

Shmuel: Yes.

Hasia: When there was a surrender.

Dov: How did it happen?

Shmuel: I was notified that I could go back if I wanted to.

Hasia: And if he wanted to stay, he could stay.

Shmuel: The director of the factory also told me that if I stayed, I would be given better conditions. He said to me, “Where will you go? There’s nowhere to go. Every place that the Germans occupied has been destroyed”.

Dov: Did you hear anything about Lithuania?

We heard rumors that there were horrific pogroms.

Shmuel: We heard rumors that there were horrific pogroms in the places where the Germans had been. We had no idea how many, but it was even in the newspaper that in the places where the Germans had been—

Dov: Did you read newspapers from Lithuania?

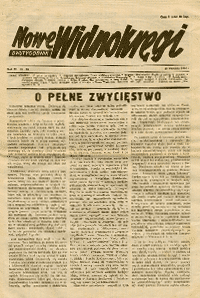

Shmuel: Once there was an article in the local newspaper.

Dov: You weren’t able to get Lithuanian newspapers? Tarybų Lietuva?[NOTE]Tarybų Lietuva (Soviet Lithuania): a newspaper published in Kaunas from 1940 to 1950

Shmuel: No. But there were Polish people who got Polish newspapers. They got Nowe Widnokręgi[NOTE]Nowe Widnokręgi (New Horizons): A Polish magazine published from 1941 to 1946 and other Polish publications.

Dov: From where? From the “Joint”?[NOTE]American Joint Distribution Committee

Shmuel: From the Z.P.P., the Union of Polish Patriots.[NOTE]Związek Patriotów Polskich, a social welfare organization for Poles in the Soviet Union, 1943-1946

Dov: But you yourself didn’t get newspapers from anyone?

Shmuel: No, I didn’t get any.

Dov: Did you know that newspapers were being given out?

Shmuel: I knew. In fact, there was a Lithuanian man who gave me papers several times. He was a Jew. I think it was Berl Friedman.

Hasia: I remember that he went to Tashkent to collect merchandise and he had no money for a return ticket to the factory in Yangiyul. So I told him, “Why do you need a ticket? If you go there with a ticket, you’ll never come back to the factory. Let’s sit on the running board of the railroad car, and we’ll go back.”

Dov: You went with him?

Hasia: Yes.

Dov: By this time the Lithuanian government had already discovered you?

Shmuel: Yes, the Lithuanian government had discovered us.

Dov: Did they assist you a little?

Shmuel: They helped a little.

Dov: Was it worth anything, the assistance that they gave you?

Shmuel: Yes. They gave us linens and— I didn’t use them for myself. I sold them all so I could buy a piece of bread.

Dov: Where was Yangiyul?

Shmuel: It’s 30 kilometers from Tashkent, on the Tashkent-Samarkand road.

Dov: Tashkent was full of Jews at that time. Did you know that?

Shmuel: I hardly saw anyone.

Dov: And there were many Jewish children from all around Lithuania. Had you heard about that?

Shmuel: No, I only heard this when I went to Vilna in 1946.

Dov: After the war, were medals given out?

Shmuel Kovnovich

in the 1970s

Shmuel: Yes, there were medals.

Hasia: Stakhanovite.[NOTE]Stakhanovite: a worker in the former Soviet Union who was exceptionally hardworking and productive

Shmuel: But Jews generally didn’t get medals, even if they deserved them.

Dov: Were there many Jews?

Shmuel: There were lots of Jews—from Poland, Bessarabia, Bukovina.

Dov: What percentage were Jews? A half? A third?

Shmuel: Certainly a third.

Dov: Were these mainly people who were sick?

Shmuel: Yes, mostly. There were also Polish people who weren’t sick, but since they didn’t want to accept Poles, those who were there left, and some were mobilized into the Russian army.

Dov: What did the Polish Jews prefer?

Shmuel: The Polish Jews would rather work in a factory than serve in the army.

He couldn’t take a bit of sugar from the factory,

and I was able to take little bags of it.

Dov: Did they manage better than you?

Shmuel: They adjusted better than I did.

Dov: I understand. It’s hard for Lithuanian Jews to cheat.

Hasia: He couldn’t take a bit of sugar from the factory, and I was able to take little bags of it.

Dov: Who can match the people of Vilna? [laughter]

Hasia: Vilna has built itself up beautifully.

Dov: How long since you’ve been here [in Jerusalem]?

Hasia: We’ve been here six years. Too bad we left Vilna. We can’t forget. Can you compare Ir Ganim[NOTE]a neighborhood in Jerusalem to Vilna?

Shmuel: We can’t forget the troubles we had.

Hasia: I came back and couldn’t find my entire household. Out of my large family, not a single person survived. Not a single one. I’m the only one left from a large family.

Dov: From your shtetl Trashkun, were there any people who took revenge on the Lithuanians?

Shmuel: There were some after the Germans were driven out in 1944, I believe. Many of the Lithuanians who collaborated with the Germans went into the woods.[NOTE]Pro-German partisans known as the "Forest Brothers" continued to wage a guerilla war against Soviet rule after the end of World War II. For various reasons—they probably didn’t want to leave their families, or they thought the Soviet army was there only temporarily—they went into the woods. Then there was an edict called legalization.

an edict called legalization

Dov: Rehabilitation?

Shmuel: Rehabilitation or legalization, it was called.

Dov: A pardon is what it meant.

Shmuel: That if these people came out of the woods of their own free will, they would not be punished and they could take up any work they wanted. My friend Konkurovich encountered one such man in the post office in Vilna. He noticed him and immediately went to a military officer who was passing by. He told him that this person had been in the woods and had participated in the slaughter of Jews. But the man showed him a document that he had been legalized, so the officer didn’t do anything to him.

Dov: Before the war, did many Jews from your shtetl come here [to Palestine/Israel]?

Shmuel: Yes, there were quite a few halutzim[NOTE]Halutzim (Pioneers): young Jews who trained for agricultural settlement in Palestine who came and are here now. One of them came here directly after the war, through Poland.

Nechama & Yerachmilke Voskoboinik

Dov: Who is that?

Shmuel: A girl from the Voskoboinik family.[NOTE]Nachman Voskoboinik and his wife Sora-Tzipe (née Reznikovich) had three children: Ziskind (1911-1952), Yerachmilke (1914-1944), and Nechama (1919-2007).

Kovnovich family, Vilnius (1953)

(enlarge)

Dov: Nechama?

Shmuel: Yes, Nechama.

Dov: Was Yerachmilke also from your shtetl?

Shmuel: Yes, Yerachmilke was her brother. He was murdered in the Kovno Ghetto.

Dov: Do you have anything else to add?

Hasia: No.

Dov: Thank you very much.

Shmuel: Thank you for recording and for listening to my story.

E N D

Full Audio in Yiddish

(also available on YouTube, audio only) (Yiddish transcript)

This is one of 611 interviews by Dov Levin that were deposited in the Oral History Division of the Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.