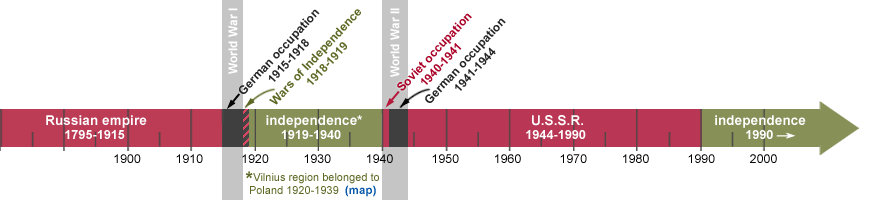

Control of Lithuania

in the 20th Century

LITHUANIA was controlled by the Russian empire throughout the 19th century, by the Soviet Union during much of the 20th century, and occupied by Germany during both world wars.

(For a thorough historical overview, see Dov Levin's YIVO History of Jews in Eastern Europe: Lithuania.)

First Decade of the Twentieth Century

CONTEXT: At the dawn of the 20th century, Lithuania was still part of the Russian empire. A wave of nationalism brought demands for independence but also an increase in inter-ethnic tensions. Before, during, and after the Russian Revolution of 1905, sporadic outbreaks of violence against Jews occurred in cities and towns throughout the Pale of Settlement.[NOTE]Pale of Settlement: region within the Russian empire where Jews were restricted to living.

The underground Bund press and official reports not only from Vilna and Kovno but also from many small Lithuanian towns such as . . . Troškūnai . . . mention that there were rumors that on a certain day, usually during Christian or Jewish holy days, Jews would be “dealt with”; that insults had been exchanged; that there had been small conflicts in which the parties involved were obviously divided along ethnic/religious lines. [1903-1906]

— Darius Staliūnas, Enemies for a Day: Antisemitism and Anti-Jewish Violence

in Lithuania under the Tsars (Budapest:CEU Press, 2015), pp. 174-75.

On 24 June 1904 there was a big fire which destroyed almost the entire center of the town. The tavern at the corner of Vytauto and Vilniaus streets near the church was also ruined. (map) The story goes that the Jews wanted to rebuild the tavern there but the townspeople were against it. They put a cross at that place so that the Jews would not build there and would move to another area instead. After the fire, people started to build brick houses. In this part of the town most residents were Jews, so the area became known as the Jewish quarter.

— Troškūnai, edited by A. Zdanavičienė, Troškūnai Townsmen Association (1996), page 20.

Translated from Lithuanian by Ya'arit Krakinowski Glezer.

World War I

NOTE for family researchers: Many vital records were destroyed by a fire in Trashkun during World War I.

CONTEXT: Germany declared war on Russia in 1914. The steady stream of Russian defeats in Lithuania at the hands of Germany brought devastating consequences to Lithuanian Jews. Relations between Jews and ethnic Lithuanians had been civil, but now Jews were accused of espionage and treason, and targeted as the cause of Russia's defeats. Anti-Semitic rumors led to attacks, trials and executions. Even though the rumors were proved groundless, Russian authorities used them to justify the forced expulsion of tens of thousands of Jews in the spring of 1915. Lithuanian Jews who avoided exile and remained in their towns fell victim to pogroms perpetrated by Cossacks (Russian army irregulars) as the Russian army retreated. Trashkun was one of fifteen towns in Kovno province that suffered pogroms.

Mobilization and Displacement

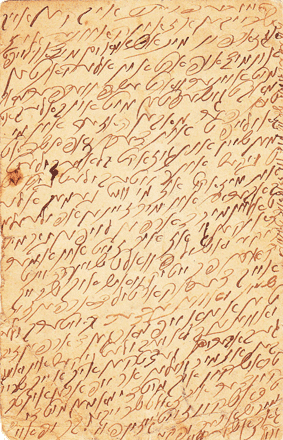

On 20 July 1914, a mother sent this postcard from Kovno to relatives in America. Although she wrote that her family was going to Trashkun, they couldn't stay there long and had to flee into Russia.

Sora-Rivka

Godashevich

Dear loved ones, I can tell you that in Kovno there is an edict from on high. People are running and driving in all directions. In a word, businesses are closing, homeowners are shutting their houses, and people are fleeing. They're calling up men with blue and red cards [types of exemption from military service], and people say they're recruiting all young men, and even we ourselves are forlorn. We have to leave, and we just thank God that you're in America. The Friday that I'm writing you this postcard, red card holders must show up, and tomorrow blue card holders and all young men. Now I can tell you that we're going to Trashkun, me with Mother and the children. You should write to me in Trashkun. Be well, from me, Sora-Rivka Godashevich.

— Sora-Rivka Godashevich (née Solomon)

translated from Yiddish by Jonathan Felendler and lightly edited

The Russian Army

Dov Ber

Ichikovich

In 1914, the First World War broke out, and Jewish boys were conscripted to the army. My zeyde tried to dodge the army but he was eventually caught. And because he was so strong, he was appointed to work in the stores rather than go to the front. Anybody who went to the front virtually never came back. . . . And in all the years he was in the army, he never ate treyf. He only ate bread and vegetables. In the middle of the war, he contracted typhus fever. He was critically ill. He nearly died. He lost all his hair. But (Boruch Hashem) he was strong, and he made a recovery.

— Selwyn Bolel, speaking of his grandfather Dov Ber Ichikovich ► see VIDEO for more

Bentzl Itzikovich

My father was drafted when he was young, so he went to hide in the woods. The government threatened his mother that they would put her husband in jail if their son didn't report to the draft, so my father came out of hiding and had to enter the army. When [my father's four older brothers] heard about this in America, they put together $500, a huge sum then, and sent it to their brother Velve to get my father out of the service. My father poured water into his ears, then went outside so the water would freeze. This landed him in the hospital. While he was there, Velve traveled to the hospital and waited outside until he saw the doctor leave the building. Velve followed the doctor in the street and offered the $500 as a bribe to get my father out of the army. And it worked.[NOTE]Bentzl's 1920 internal passport application indicates that in 1914 he was discharged from the military "after an illness."

— Frank Kovitz, speaking of his father Bentzl Itzikovich

Accounts of the 1915 Pogrom in Trashkun

In July our [Russian] retreating forces began passing through the province. They behaved properly by paying in shops, and even forewarned Jews about Cossacks in some places, advising them to evacuate . . . In Trashkun, Russian troops passed through starting on July 9. On July 12, a dragoon arrived and the townspeople became anxious. A pogrom began on the night of the twelfth. The soldiers broke down doors, smashed windows, broke into homes, looted, and beat people. From morning to night on the thirteenth one heard screams all around, the sound of shattering glass and dishes, and cracking furniture. Feathers were flying from ripped up pillows, flour was spilled from sacks. The rioters took valuable and worthless objects alike.

— G. M. Erlikh, who helped compile a wartime narrative history titled From the "Black Book" of Imperial Russian Jewry, quoted in

Pogroms: A Documentary History, ed. Eurene M. Avrutin and Elissa Bemporad, Oxford University Press, 2021, p.121.

On 13 July [1915] the Cossacks carried out a dreadful pogrom in Trashkun. Not one unbroken window pane remained in Jewish homes, not one Jewish store escaped being robbed. The women were violated. The Jews fell at the feet of the Cossack commander and pleaded for him to stop the pogrom, but he coldly replied that his Cossacks would not pay attention to him. After the wild Cossacks had taken everything they wanted, they forced the Jews to leave Trashkun. The unfortunate Jews wandered around on the roads and through the villages and slept in the open. The peasants had been sharply warned not to allow Jews into their houses or to show them any pity.

— "The Pogroms Against the Lithuanian Jews Who Avoided Expulsion," Section 6 of "The Exile of the Lithuanian

Jews during the Conflagration of the First World War (1914-1918)" by Louis Stein in Lite vol.1,

ed. Mendel Sudarsky and Uriah Katzenelenbogen. New York: Jewish-Cultural Society, 1951.

1915 Pogrom in Trashkun: Account by Jewish Committee to Aid War Victims

dated 27 July 1915 (two weeks after the events)

On 9 July [1915] the retreating Russian troops began to pass through Trashkun. At first they treated the residents well and paid for everything. On 10 and 11 July more troops arrived, and they also passed through peacefully. Then on 12 July there arrived some dragoons (cavalry). When two officers stopped to ask directions, a crowd of Jews and peasants surrounded them and answered their questions.

“So, do you have many spies?” the officers asked. “We don’t know. How would we know?” the residents answered. Then some said, “Oh, you mean these spies, the Jews? Wait, we’ll count them.”

The atmosphere in town became tense and rumors spread. The soldiers became more and more threatening, and the Jewish population began to think about leaving. At 2 a.m on the night of 12-13 July, the Jews were already preparing and packing when dragoons came to the house of Wulf Itzikovich. They shoved him and started to attack him. He had barely begun to beg them not to beat him when they dragged him into his shop and started pulling things off the shelves. When they left the house, they kept what they had taken. Meanwhile, soldiers were going through the entire town, battering houses and shops, breaking doors, bursting in, smashing windows, stealing, and beating people.

On 13 July from morning till night you could hear the sounds of screams, shattering windows and dishes, crashing doors and furniture. Feathers flew from ripped pillows. Flour spilled from bags. The soldiers took things they needed and things they didn’t need. They destroyed and spilled things for no reason. They offered items to the peasants and sold them flour for 10-20 kopecks a bag.

Soldiers stopped Yisrael Yanus on the road and asked him, “What’s your name?” “Yanus.” “Watch out, don’t touch anything or hide anything. The government will take it all, and we’ll take your money.” One of the soldiers approached the peasant Matsyukis, who was keeping Yanus’ belongings in his house. The soldier said to Matsyukis, “You’re not allowed to hide things for the Jews.” So Matsyukis threw Yanus’ possessions into the street, where they were stolen on the spot.

Soldiers approached Henoch Vinik[NOTE]Henoch Vinik (~1859-1922), a merchant., seized the old man by his beard, accused him of helping the Germans, and robbed him. A soldier said to Henoch’s daughter Chana, “Give me a match,” and she gave it to him. He was about to pay when she asked him, “Why? They’re taking everything anyway, so you don’t need to pay.” He said, “No, I want to pay you.” When she opened the cashbox to make change, the soldier snatched the box from her hands and ran away with it. Other soldiers attacked Chana, and she barely managed to save herself.

In the evening an officer arrived. He was offered tea, and people asked him to make the soldiers leave. He replied, “They won’t obey me anyway.” In his presence, soldiers opened dressers and confiscated the clothing.

Women were raped, but no names were disclosed. Soldiers broke into Chana Solomon’s[NOTE]This could be either Chana Solomon b. 1889 (daughter of Itsyk and Raycha) or Chana Solomon b. ~1898 (daughter of Fayvush and Chava-Ester), who later married Leybe Pevzner. house and grabbed her. She started to scream and Fayvish Skudovich came running to protect her. When the soldiers attacked him, she managed to get away.

Soldiers broke into the house of Rabbi Sholom Eizer[NOTE]Sholom Eizer, born 10 November 1865, son of Abram Itzik. and took valuables, pillows, and samovars. They broke into the house of Sheva Degutnik,[NOTE]Sheva Degutnik (1877-1928) née Solomin, was the first wife of Mortkhel Degutnik (1874-1941). the wife of a reserve soldier who was away on active duty. They took everything in the shop and the attic, scattering things everywhere. When Sheva tried to hide one item, the dragoons noticed and one of them said, “Give it back, Jewess. You’re hiding something from me.” They attacked her and she gave it to them so they would let her go, and she managed to get away.

They looted the shop and house of Paya Rutenberg, took all the clothing, pillows, and a pair of earrings, and took Yisrael Rutenberg's watch.

In the morning they broke into the house of Boruch Skudovich, took 70 rubles from him, and stole 100 rubles’ worth of merchandise. They took 85 rubles from Hirsh Skudovich and stole another 200 rubles from his home. He tried to resist and they threatened to kill him. They robbed the shop of Zelman Waldman and took property from his apartment—copper utensils, pillows, and samovars. They robbed Yakov Kushner and Liba Vin.[NOTE]Pera Liba Fin, born in 1866, married Mendel Reznikovich in 1900. Malka Fram[NOTE]Malka Fram (1853-1923) née Shapiro had become frightened and gone to Kovarsk [Kavarskas] (map) after leaving her possessions with Reznik on the outskirts of town. When she returned she discovered that almost everything had been stolen, and when she asked for what was left, they wouldn’t give it to her. The same thing happened to Boruch Yankel Reyzent.[NOTE]Boruch Reyzent, son of Shmuel Reyzent, father of Abram Reyzent

They smashed Daniel Reznikovich's bakery. Jewish soldiers helped him pack up what was left and transport it to Kovarsk, but Reznikovich and his family weren’t allowed to stay there and had to keep moving. They waded across the Šventoji River (map) at night with their child who had scarlet fever, and spent the night in a field. Many people were beaten, including Abba Segal and Mendel Kutnik. A dragoon on horseback rode directly into Hirsh Skudovich’s wife [Leah]. She fell and the horse trampled her underfoot.

On 14 July, Sholom Osherovich returned to Trashkun from Vilna [Vilnius]. As he approached his house, he saw an officer standing there. The officer ordered him to halt, and two other officers came over and started to beat him. They hailed a Cossack and ordered him to tie Osherovich to his saddle. The Cossack tied him to the saddle, got on his horse, and took off at a gallop, forcing Osherovich to run behind the horse. When they reached the edge of town, the Cossack untied him and took him to Montvil’s estate, where the corps had its headquarters. An officer came out and asked, “Are you a spy? And who arrested you?” The Cossack answered, “Prince Pushkin.” The officers sent the Cossack back to get orders in writing. Then they stripped Osherovich of his clothes and underwear and took everything he had on him. When the Cossack came back, they imprisoned Osherovich with the other Jews and tortured them for half the day before releasing them.

There were no orders from higher authorities to evict the Jews, but early that morning the soldiers started chasing them out of town. “Get out, Jews, till there’s no trace of you left. The Germans will be waiting for anyone who stays behind.” The soldiers chased the Jews and beat them if they didn’t move fast enough. The Jews ran whichever way they could, taking nothing at all with them. The road was filled with soldiers, so the Jews ran into the woods and tried to hide from the peasants. Some peasants reluctantly allowed Jews into their homes, but when the soldiers found out, they searched the peasants’ huts and prohibited peasants from taking in Jews. So the Jews wandered in the fields and the surrounding area. Some went to Aniksht [Anykščiai] (map) or other villages.

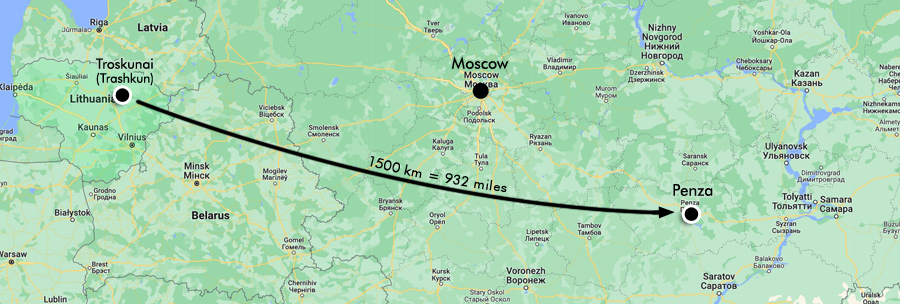

Yudel Lachternik tried to stay in Trashkun for the night. “What, Jew, you’re still here? Get out! Because of you Jews, too many of us have spilled our blood.” Yudel begged them to let him stay till morning, but they took no pity on him. So he loaded his belongings into a cart, but the soldiers tossed them out and kept them. Yudel left Trashkun with two pillows and arrived in Aniksht during the day of 14 July, but looting was going on there too. The Jews had to leave Aniksht and spent the night in the woods or in the fields. Some of them made it to Malat [Moletai] (map). From there, they were sent to Kiev and Penza provinces (map).

(Account by the Jewish Committee to Aid War Victims, whose agents traveled freely at the front lines during 1914-1917)

— Russian State Historical Archive,

provided by Anatolij Chayesh, translated by Sonia Kovitz

Report by a representative of the Jewish Committee to Aid War Victims

(written to a colleague in Petrograd on 20 September 1915)

Before the Germans captured Trashkun and Aniksht [Troškūnai and Anykščiai] (map) in this region, the excesses of the Cossacks reached colossal bounds. All Jewish property in the region was completely plundered, there were murders and rapes, and so on. Cossack unruliness reached the point that in Trashkun they were about to raise on a pike the Red Cross doctor Tomarovsky, who was intervening on behalf of those being plundered. Prosperous people and even the rich were impoverished within a few minutes. Furthermore, the commanders of some army units evacuated all Jews in places under their jurisdiction, sometimes giving people only 15-20 minutes to leave.

— Russian State Historical Archive, quoted in

"On the Front Line in Lithuania in 1915:

Narratives of Jewish Eyewitnesses (Part II)"

by Anatolij Chayesh, August 2005, translated by Gordon McDaniel

1915 Pogrom in Trashkun: Eyewitness Account of Sholom Eizer [NOTE]Sholom Eizer, born 10 November 1865, son of Abram Itzik.

The army came on July 9th, but it was quiet until Sunday, July 12th. On Sunday two Cossacks came to the house and we fed them. They warned us to gather our belongings and leave. I got a cart to carry 36 Torahs. After they were packed, at 2 a.m., the last convoy entered the village, and at 5 a.m. they started plundering. My son and I escaped through a window, taking with us a bag of silver. We hid the bag in the synagogue in the bima. We thought the silver would be safe there, but at 10 a.m. soldiers ransacked the synagogue and took everything. They threw the books around and trampled them with their feet. Near the synagogue, in the house where Rabbi Meyer Feldberg was staying after fleeing from Survilishik,[NOTE]Rabbi Meyer Feldberg, born in 1876 in Keydan (Kėdainiai), lived with his wife Sarah in Survilishik (Surviliškis), 82 km/51 miles southwest of Trashkun. Cossacks broke in, searched the rabbi and took his watch. He gave them 20 kopecks as an appeal for mercy, and hurried to leave since he was not completely well, while his wife stayed behind to save the household.

The soldiers came in and unpacked everything. They divided the loot among themselves and the peasants. They lined up the Torahs on the floor, breaking the tips of the scrolls. They searched my wife. When asked to leave a pillow, the soldiers answered that they suffered more than us (the Jews). Two Jewish soldiers salvaged two feather beds by pretending to take them but returning them later. The soldiers would not allow us to take the Torahs on the cart. Finally they arrested everyone and sent us to Aniksht [Anykščiai] (map) under guard. But on the way, we found a cart. I wanted to (use it to) transport invalids out of Trashkun at 10 a.m. I started to seat a wounded soldier, Berel Skudovich, who had been in the Petrograd military hospital, a recipient of the Cross of St. George [Russian military decoration]. The soldiers stopped me and beat me with a whip. It was impossible to take anything with us. The soldiers threatened to send us to Petrograd.

They caught the Bageyler girl,[NOTE]Possibly Chaya Sora Bageyler, daughter of Eliash Shepsel Bageyler and his wife Leya (née Yoffe). 25 years old, but she escaped. Naftoli wanted to protect her, and for that he was beaten. Zalk, 80 years old,[NOTE]Possibly Shlioma Zalk, born in ~1845 says that they shot Simon from Rogeve [Raguva] (map) and hanged the butcher, Elye Reznik, who was mentally ill. Etel Muler, 70 years old, was shot and so was Kopel Shirman. But this latest information is based on the stories of neighbors.

Sholom Eizer (Eyzer), age 50, rabbi [or shochet] from the village of Trashkun

(Testimony taken by the Jewish Committee to Aid War Victims, whose agents traveled freely at the front lines during 1914-1917)

— "On the Front Line in Lithuania in 1915: Narratives of Jewish Eyewitnesses (Part II)"

by Anatolij Chayesh, August 2005, translated by Gordon McDaniel

1915 Pogrom in Trashkun: Eyewitness Account of Sholom Osherovich

It was quiet until July 12th. On Sunday, July 12th, the retreating army occupied the entire town. There was panic. Plundering, destruction and rape did not bypass Trashkun. The residents began to leave town. Many went to Aniksht [Anykščiai] (map). I hoped to return the next day from Aniksht to Trashkun to get at least some of my property. But alas, when I got back to Trashkun, I met an officer who asked me where I was going. I answered that I was going to get my belongings. He politely hurried me along and said it was impossible to stay in town for long because the army was retreating. Not far from my house, a Cossack officer stopped me and took me into a yard. Soon two other officers appeared. One of them, without a word, pulled a thick picket from the fence and started to beat me. He hit my left arm, leaving a wound. He hit me on the left side of the small of my back, with the same result. I couldn't touch my body even lightly because of the pain. They beat me until the picket broke.

Then the same officer who ordered them to beat me called a Cossack and ordered him to tie me to a horse so I would have to keep up with it, and sent me to the commander like that. The Cossack rode around town at full speed and I ran after him, tied to the horse. Only at the town border did the Cossack take pity on me and untie me, and then I walked freely behind him. The commander greeted the Cossack with the words, "What spy did you catch? Who sent him?" "Prince Pushkin," I think the Cossack answered. I can't swear to the exact surname. The commander, with no evidence from the Cossack officer, didn't know how to punish me. Besides, he was in a hurry to retreat, which I understand saved me from a flogging. I was handed over to another soldier, who ran to look for "Prince Pushkin." When he came back, they searched me and took whatever they could, even my socks.

Then they let me go and sent me, along with other Jews, out of town under guard. They drove us mercilessly. Long convoys stretched along the road. Wagons of refugees were pushed off the road. Several times wagons were overturned. Fainting women and children were commonplace for us. How we got to Aniksht alive, I don't know.

Sholom Osherovich, age 39, a worker in the emigration office first in Ponevezh and later in Trashkun

(Testimony taken by the Jewish Committee to Aid War Victims, whose agents traveled freely at the front lines during 1914-1917)

— "On the Front Line in Lithuania in 1915: Narratives of Jewish Eyewitnesses (Part II)"

by Anatolij Chayesh, August 2005, translated by Gordon McDaniel

(See also "The Expulsion of the Jews from Lithuania in the Spring of 1915" by Anatolij Chayesh, 2005.)

Exile during World War I

When large numbers of Jews were expelled from Lithuania in the spring of 1915, they fled east into Russia. Many Jews from Trashkun went to the city of Penza. Life in exile was not easy, especially as revolution and civil war soon broke out in Russia. Most Jews returned to their homes in Lithuania within a year after the Russian Civil War ended in November 1920.

During World War I many Jewish families from our shtetl Trashkun were evacuated deep into Russia. The journey was very difficult, and when people arrived they lived in crowded soldiers' barracks. Illnesses spread and many people died, although no one from our shtetl. Food was provided [by Jewish aid societies], and people without shoes were given material to make them.

— Berl Glezer, My Shtetele Trashkun, Part II

While in Penza, Chana-Basya's son Moyshe-Itzik married a girl named Tzivya, and Hirshl married Tzivya's sister. I remember very well what Tzivya's sister looked like. She was very tall and beautiful. But something terrible happened in Penza in 1918. While she was sitting on the windowsill of their second floor apartment, there was a clash between the Red and White armies. She was hit by a bullet and died. It was a great tragedy for the Shepshelevich family, one of many tragedies to strike our family. But life went on.

— Berl Glezer, Memories of the Shepshelevich Family

After the war, people began to think about moving back home. People thought that if they returned to Trashkun the sun would shine more brightly there and it would be easier to make a brighter and nicer life. The trip home was also very difficult and people returned from the long journey exhausted and sick. Other than Yoshe Saltuper the feldsher [unofficial medical practitioner], little medical help was available and there were few remedies and medicines. Even with only a few, Yoshe was able to help people. The Trashkuners who had not been evacuated were back on their feet by then, with food supplies and cellars full of potatoes. Some of the hungry returnees to Trashkun demanded that the well-off people share their stored food with the families who had nothing. When that did not happen, people tore the locks off the doors of the storehouses and distributed the potatoes among the poor.

— Berl Glezer, My Shtetele Trashkun, Part II

Children in World War I

Account of Alter Resnick

Melech was my brother, younger than me by several years. . . . He passed away in Traskun, before I was bar mitzvah, after the war [World War I], while we were running from countries, from city to city, from the gangs, from the Cossacks and other bands that were making pogroms and things like that. We had no time for bar mitzvahs. By the time we stopped running, the time for my bar mitzvah had passed. We couldn't have had it in the forest, so we never had it anywhere.

— Alter Resnick (born Chaim Daniel Reznikovich in Trashkun in 1906)

Full interview with Alter Resnick by Shirley Kalb and Sam Puner on 26 February 1979

(Bernard Margolis archive, supplied by Jeff Meyerson)

Newspaper Account of Supovitz Brothers' Hardships and Rescue (1920)

NEWS CLIPPING Two young brothers, Myer and Abraham Supovitz, 19 and 20 years old, brown as berries and hardened by exposure, arrived at the Auburn home of their aunt, Mrs. Ethel Supovitz, 26 Secont St., Auburn, after a series of adventures in walking halfway across Europe in the past two years in their escape from Russia and then from the Germans to reach freedom. The boys had been born in Lewiston, but their father died when they were very young and their mother took them back to Europe where she remarried and where they were living in Russian-held territory when the Revolution broke out. Neither had spoke English, but the Journal interviewer had no trouble, as kinsmen were only too glad to translate the hair-raising story the boys told very matter-of-factly. On one of their "jaunts" they walked 19 days with virtually no food. Myer was captured by the Germans and forced to work for them for a half-pound of black bread each day and the privilege of sleeping in a barn. Then the brothers were united but again were forced to work for Germans until they managed to escape, only to be drafted into the Lithuanian army where they were fortunate enough to encounter an American who, hearing their story, contacted the American Consulate, which, in turn, got in touch with Mrs. Supovitz in Auburn. She and her family immediately started proceedings that resulted in the two young men arriving at her home in Auburn where a warm welcome awaited them.

— The Lewiston Journal, Lewiston, Maine.

Article originally published in 1920,

re-published in 1970

under the heading 50 Years Ago Today – '20

NOTE: Myer and Abraham Supovitz were sons of Harry Supovitz (born in Trashkun as Hillel Wulf Skudovich), who had immigrated to the United States in 1899. The boys' aunt was the widow of Harry's older brother Mendell Supovitz (born Menachem Mendel Skudovich). Mendell's family had immigrated to the United States in 1905.

Between the World Wars

Nochum

Chaimovich

Shlomo Kovnovich

After World War I, once Lithuania gained its independence, a law was passed granting some autonomy for minority communities. As a consequence, in 1921 the Jews of Trashkun elected a Jewish Community Council (va’ad kehila) to manage Jewish cultural, welfare, social, and educational affairs. The chairman of the council was Shlomo Kovnovich. The other members were Rabbi Yakov Moshe Shmukler, Gershon Solomon, Nochum Chaimovich, Tzvi (Hirsh) Shepshelevich, and Y. Vinik (first name unknown). This project did not last long. In 1925, all such councils were disbanded.

— Josef Rosin, "Troškūnai (Trashkun)," Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

and "Minority Rights" (Jewish Virtual Library)

List of Jewish Families Living in Trashkun

compiled by the Jewish Community Council of Trashkun in the years between 1920 and 1924

Shmuel Kovnovich

As Lithuanian nationalism and anti-Semitism grew in the larger society, many Jews felt that their only hope for equal rights was to live under Soviet rule. Shmuel Kovnovich served as secretary of the local communist party.

— Josef Rosin, "Troškūnai (Trashkun)," Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

and Berl Glezer, My Shtetele Trashkun, Part II

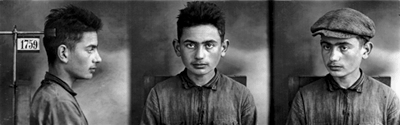

From the mid-1920s to mid-1930s, many people, including Jews, were arrested for being communists. Two brothers from Trashkun, Mikhel and Sholom Kikhel, were arrested in Kovno in 1929 for being members of the communist party.

police photos: Mikhel Kikhel, age 20 (1929) (enlarge)

police photos: Sholom Kikhel, age 15 (1929) (enlarge)

There was a primary Jewish school at number 9 Basanaviciaus Street (map). The only document left from the school is the register from 1939-1940. The title of the register shows that the Jewish school was part of the Lithuanian school. There are 37 Jewish names in the register. Pupils studied the Hebrew and Lithuanian languages. The teacher was Ms. Zelionskaite. Some Jewish names can be found in Lithuanian classes. The children perished in the war. . . .

✥

The cookies from the Jewish bakery were the favorite treat of the town's children. Most of the shops belonged to Jews; only two were Lithuanian.

— Troškūnai, edited by A. Zdanavičienė, Troškūnai Townsmen Association (1996), page 46.

Translated from Lithuanian by Ya'arit Krakinowski Glezer.

Berl Glezer's description of life in Trashkun between the wars:

My Shtetele Trashkun, Part II

World War II and the Holocaust

CONTEXT • Soviet Occupation: After 20 years of independence, Lithuania fell under the sphere of influence of the Soviet Union under the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Soviet Army entered Lithuania on 15 June 1940. The Soviet occupation was repressive. All land was nationalized, and religious, cultural and political organizations were banned. Thousands of Lithuanians, including two Jewish families from Trashkun, were declared "enemies of the people" and deported to Siberia, where many perished. A nationalist coalition called the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) was formed, with Nazi backing, to oust the Soviets. The LAF initiated an anti-Semitic "Lithuania for Lithuanians" movement and incited anti-Jewish violence. Jews were accused of being Communists and blamed for the suffering under Soviet rule.

• German Invasion: On 22 June 1941 Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, a surprise attack on Soviet-occupied territories, including Lithuania. Many ethnic Lithuanians welcomed the Germans as liberators. The LAF's Provisional Government ruled for only six weeks24 June to 5 August, 1941 before the Germans seized political control, dashing Lithuanian hopes for renewed independence. In those six weeks, the LAF enacted anti-Jewish laws that helped set the stage for mass extermination. (See LAF propaganda and regulations relating to Jews [PDF].) Once the Germans were in power, local armed supporters of the LAF—recognized by their white armbands—were organized into battalions under the control of German Einsatzgruppen. These battalions carried out pogroms and assisted the Nazis in rounding up, transporting, guarding, and shooting Jews.

Aside from the small number of Jews who were able to escape into Russia in the opening days of the war, no Jews living in Troskunai in June 1941 survived World War II. After the war, no survivors returned to live in Troskunai.

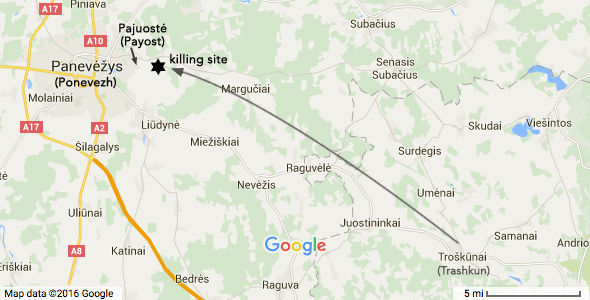

Most of the Jewish people of Troskunai were shot to death in large pits which were dug in the Pajuoste forest, a few miles east of Panevezys. This was the work of the Einsatzgruppen, mobile killing units that followed behind the German front and whose job was to round up and murder all the Jews they could find. Most of the actual shooting at Pajuoste was done by Lithuanian volunteers under the supervision of the German Security Police. The massacre of Troskunai Jews at Pajuoste occurred on 23 August 1941.

But in July 1941, even before German soldiers reached Troskunai, some Lithuanians were incited to violence by the anti-Semitic propaganda of the Nazi-backed Lithuanian Activist Front, and took advantage of the chaos to go on several killing sprees, leaving approximately 15 Jews dead in Troskunai. These Jews were buried in a small mass grave adjacent to the Old Jewish Cemetery.

Accounts of the Shoah in Troskunai

Many Jews were killed by Lithuanians before the Germans established political control and organized large-scale mass murders.

On 10 July 1941, Troškūnai local white armbanders killed 8 or 9 Jewish men on the premises of the local school. In mid July, Troškūnai white armbanders shot 5 or 6 Jewish men at the Jewish cemetery. In August 1941, the remaining Jews of Troškūnai (about 200 people) were transported by white armbanders to the Panevėžys ghetto. There, on 23 August 1941, they were murdered along with Jews from the city of Panevėžys and its surrounding areas.

— Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania and Yad Vashem

The Jews of Troškūnai became victims of the Shoah on 10 July 1941. A unit of local Lithuanian activists led by Vladas Parojus arrested 10 Jews and 10 Lithuanians. They herded the people into the primary school and locked them in a classroom. After having a few drinks and armed with rifles, the gunmen got ready to commit their crime. They came into the classroom and ordered the Jews to stand in a row on one side of the room and the Lithuanians on the other side. Then they opened fire. Afterwards they put the bodies into two horse carriages and brought them to the cemetery, and let other Jews accompany the carriages. When they came to the cemetery, the gunmen opened fire again and killed the Jews who had escorted the procession.

— Jewish Community of Panevezys (translated from Lithuanian by Lauras Sabonis)

Father Antanas Juška was Troskunai's parish priest. He is said to have hidden two young Jews in his home. In his sermons, the priest repeatedly lamented the killing of innocent people, and rebuked his parishioners for plundering Jewish property.

— Jewish Community of Panevezys

Eyewitness Account of Pastor Antanas Juška

Awful things started to happen in Troškūnai. There was a group of men . . . They wore white armbands. They gathered all the Jews and brought them to the school building, which became the ghetto. From there they were taken to sweep the streets and do other work. From the church window I saw how the men with white armbands took four Jews from the ghetto and shot them in the square in front of the church. After that, other Jews were brought to take away the bodies and bury them somewhere. I did not ask who the victims were or who carried out the execution. I was afraid. One afternoon all the Jews were taken to the railway station by the men with white armbands. No Jew ever returned.

Antanas Juška, parish priest in Troškūnai

— Troškūnai, edited by A. Zdanavičienė, Troškūnai Townsmen Association (1996), page 55.

Translated from Lithuanian by Ya'arit Krakinowski Glezer.

At the start of WWII, even before the Germans entered Lithuania, a local gang of nationalistic Lithuanians took over the town [Trashkun], murdered a Jewish man in the street and a Jewish woman in her home. They looted Jewish homes. When the Germans arrived, the gang collaborated with the Germans, forced the Jews into a poor neighborhood, harassed young Jews, and murdered them in the Jewish cemetery. Jews who resisted the gangs paid with their lives. On August 21-22, 1941, all Trashkun Jews were taken to Pajuostė [Payost] near Panevėžys [Ponevezh], the killing field for the Jews in the region. On August 23, all were murdered and buried in a mass grave in Pajuostė. After the war, survivors of the community erected a memorial for the Pajuoste victims with an inscription in Russian and Yiddish. In Trashkun itself, the authorities permitted a memorial under pressure and allowed an inscription only in Lithuanian that did not mention that the victims were Jews.

— International Jewish Cemetery Project: Troskunai,

International Association of Jewish Genealogical Socities (IAJGS)

Jews were taken from Troškūnai to Pajuostė to be killed in August 1941.

Members of a Lithuanian militia unit force a group of Jewish women to undress before their execution in the Pajuostė Forest. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Saulius Berzinis)

The mass graves are located about 6 km (4 miles) east of Panevėžys, in the forest east of Pajuostė. (maps & directions)

The major mass murder of the Jews of Panevėžys took place on August 23, 1941. Two pits about 40 meters long were dug in the forest. Before the massacre, German SS-Obersturmführer Joachim Hamann delivered a speech in which he stressed that, according to the decree of the Führer, all Jews must be destroyed. They were brought to the pits in groups and shot. Jews were brought to the shooting place by troops of the Panevėžys (10th) battalion. The Germans selected some Lithuanians to do the shooting; they carried out the execution. According to one participant in the massacre, about 70 soldiers of the battalion and 30 Germans did the shooting. Colonel P. Genys and commander of the 1st Unit of the battalion lieutenant V. Aižinas were present at the murder site. Before the shooting, each killer was given 200 grams of vodka. The Lithuanians used rifles and the Germans used machine guns. The massacre took all day. A total of 7,523 Jews were shot (1,312 men, 4,602 women, 1,609 children). Jews from different rural districts of Panevėžys district were murdered along with the prisoners of the Panevėžys ghetto. — Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania

The killings at Pajuostė, outside Panevėžys, are included in the infamous Jäger Report, a daily tally of executions by Einsatzkommando 3 between 2 July 1941 and 1 December 1941.

Testimony of Itzhak Konkurovich

(Konkurovich family)

Itzhak

Konkurovich

Trashkun (Troškūnai), a little town in Panevėžys District about 20 km. northwest of Aniksht (Anykščiai). Prior to World War II, 100 to 120 Jewish families lived there. The town was far from the front lines. Even before the area was occupied by the Germans, wild Lithuanians gangs went on killing sprees. For example, the Lithuanian Menishkis used a wooden beam to beat Yechezkiel Chadash to death as he walked to afternoon prayers at the synagogue. He was a respected member of the Jewish community. Mina Saltuper [married name Pekl], sister of Yosef Saltuper, the well known and much loved feldsher [unofficial medical practitioner] of the town and district, was murdered in her home. (anecdote about Mina Saltuper)

Anti-Jewish laws were soon passed, requiring Jews to abandon their homes. In Trashkun the Jews had to move into the little hovels near the bathhouse, the poorest section of town.

The leaders of the group that taunted and demeaned the Jews were the following local Lithuanians: Zabodskis, the Slutskis brothers, and the Parsiliai brothers, sons of a local landowner.

The local hooligans collected a group of young Jews, among whom were the brothers Chaim and Zalman Klatchko and Hirsh Itzikovich, led them to the Jewish cemetery and ordered them to dig a pit. Hirsh Itzikovich bowed at the feet of Zabodskis, who was his neighbor, and pleaded to be spared. Zabodskis mocked Itzikovich, ordered him to run, and shot and murdered him. They also murdered the other young Jewish men of the town. The murderers went home singing songs. Passing the house of a farmer who was milking his cows, they asked for milk to celebrate and drink to the spilled Jewish blood.

Not all the Jews of the town accepted their bitter fate passively. Perl and Chaim Shumacher, Feyge and Binyomin Krasovsky, Asher Shmidt, and others without political leanings called upon the Jews to oppose the bands of robbing and murdering hooligans. They resisted the bands and were murdered in their homes.

On the 21st or 22nd of August 1941, all the remaining Jews of the town were taken under heavy guard to Payost (Pajuostė) near Ponevezh (Panevėžys), which became a dark valley of death for the Jews of the entire district. The following day all the Jews at this location were murdered. This took place on 23 August 1941 (30 Av 5701).

After the war, survivors from the Panevėžys District erected a monument at the mass graves at Pajuostė with inscriptions in Yiddish and Russian: "These are the four mass graves of the Jews of Panevėžys and the other towns of the district who were murdered by the German and Lithuanian fascists in August 1941."

Survivors from Trashkun made many requests to local authorities for a monument to be erected at the Jewish cemetery in Trashkun in memory of the young Jewish men who dug the pits and the other murdered Jews who are buried there. A monument was finally erected by the local authorities, but is inscribed only in Lithuanian and there is no mention that the victims were Jews.

— Itzhak Konkurovich, Kiryat Ono, Israel. "Trashkun (Troškūnai)"

in Yahadut Lita (Lithuanian Jewry) Vol. IV, 1984, p. 294.

Translated by Itzhak Konkurovich, Misha Glezer and Sonia Kovitz.

(Hebrew original)

Account of Miriam Shumacher Krakinowski

(Yuter family)

Miriam Shumacher

Krakinowski

VIDEO In three short videos Miriam Shumacher Krakinowski, daughter of Perl (Yuter) and Chaim Shumacher, tells how her parents and others were murdered in Trashkun in July 1941, who was buried with them in the mass grave at the Old Jewish Cemetery, and how the Jews who survived the first atrocities in Trashkun were taken to Payost (Pajuostė) to be shot in August 1941. The videos were recorded in Trashkun and Payost in 1993.

From the Israel Kaplan Collection

Testimony of Nechama Voskoboinik Halamish

(Voskoboinik family)

Nechama

Voskoboinik

Trashkun (Troškūnai). Even before the Germans reached the town, when the Lithuanians knew only that the entire area was surrounded by invading armies, a wild rampage began. People who had been friendly neighbors suddenly became accomplices in robbery and murder. The first victims were about 15 Jews.

After that, the Jews were concentrated in several houses near the synagogue, which became the town’s ghetto.

In August 1941, the Jews were ordered to pack up their valuables and essential belongings, and they were moved to Ponevezh (Panevėžys). At the railroad station people took away all their belongings, leaving them with almost nothing. After only a few days in Ponevezh, they were taken with the other Jews from the area to Payost (Pajuostė), where they were all murdered.

Only a few of the town's inhabitants were able to escape to Russia. There were also several people who had been in Kovno (Kaunas) during the occupation and survived the ghetto and the internment camps.

I learned these details from Lithuanians in the town during my visit after the war. I also heard of a Lithuanian officer in the local police who resigned because he did not want to take part in actions against the Jews.

— Nechama Voskoboinik Halamish,

testimony taken by Israel Kaplan at Kibbutz Lahavot Habashan on 24 May 1953

(translated from Hebrew)

Map of the escape and return route of Nechama Voskoboinik, 1941 and 1944-1946

Fighters from Trashkun

Of the small number of people who managed to escape from Trashkun into Russia, several young men joined the Lithuanian Division of the Red Army. Moshe-Fayvel Pevzner, son of Leybe Pevzner and Chana (née Solomon), volunteered for the Lithuanian Division and was killed in combat. Henoch Martsushky, son of Zavel Martsushky and Freda (née Vinik), parachuted from an airplane into Lithuanian territory, where he died at the hands of the Germans. Itzik Konkurovich escaped from the Kovno Ghetto and served in the 16th Lithuanian Division. Unlike the others, Itzik survived the war (see his testimony above). These details were provided by Shmuel Kovnovich in his 1965 oral history interview with historian Dov Levin. Leyzer (Lozerke) Lichtenstein, son of Abram Lichtenstein and Tamara (née Kozhenetz), also served in the Lithuanian Division. Berl Glezer wrote in his memoir that when he was in Siberia during the war, he heard that Leyzer had been killed at the front.

From the Israel Kaplan Collection

Testimony of Zalman Kikhli (Kikhel)

(Kikhel family)

Zalman Kikhli

(born Kikhel)

I was in the Shavl (Šiauliai) ghetto during World War II, and later in Dachau. I spent several years in Germany and immigrated to Israel in 1948.

I am a native of Trashkun (Troškūnai). In Shavl, I received some information about what happened in Trashkun in the early days of the German occupation. I was informed that Jews were taken from Trashkun to Ponevezh (Panevėžys), about 40 kilometers away, and they were kept for a while in Palestinke.[NOTE]Palestinke, or "Little Palestine," was a Jewish neighborhood in Ponevezh, established after World War I. I heard that afterwards all the Jews from Trashkun and Ponevezh were taken to Payost (Pajuostė), where they were murdered.

I have not heard of any Jews from Trashkun who were in hiding. Probably no one was able to survive.

At the beginning of the war, a number of young people fled from the town to Russia. Some of them joined the Lithuanian Division [of the Red Army] and were killed—Henoch Martsushky and others. One was killed while with the Red Partisans; Fayvke [Moyshe-Fayvke Pevzner] was his name. All this, I’ve only heard.

[After the war] some of the returnees from Russia—Yankel and Moshe Gottstein and others—lived in Vilna (Vilnius), some in Shavl (Šiauliai) and in Utyan (Utena).

— Zalman Kikhli,

testimony taken by Israel Kaplan at Kibbutz Givat Brenner on 25 October 1957

(translated from Hebrew)

Shmuel Kovnovich: Account and Interview

(Kovnovich family)

Shmuel

Kovnovich

Shmuel Kovnovich wrote a harrowing account of his escape from Trashkun in the opening days of the war.

In 1965, the historian Dov Levin conducted an hour-long oral history interview with Shmuel Kovnovich and his wife Hasia about their wartime experiences. After fleeing Trashkun, Shmuel made his way through Russia to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, where he met Hasia, who had fled from Vilna. Read an edited transcript in English, a Yiddish transcript (PDF), or listen to the audio of the full interview in Yiddish.

After the War: Memorials

CONTEXT: Memorials to Jews killed in the atrocities of 1941 have evolved with the changing political situation in Lithuania. In the Soviet era, inscriptions generally referred to those buried in mass graves as victims of fascism but not as Jews, and there was no mention of Lithuanian collaborators. Once Lithuania gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, monuments were updated with inscriptions in Yiddish, identifying the victims as Jews, and acknowledging that Lithuanians participated in the killings. But to this day, many Lithuanians minimize the role of ethnic Lithuanians in the killing of Jews during the war. (read more)

Memorials at the Old Jewish Cemetery in Trashkun (view map)

The original (Soviet era) monument at the mass grave in Trashkun's Old Jewish Cemetery was replaced after Lithuanian independence. The current monument has an inscription in Yiddish and Lithuanian. There is now also a memorial stone with an inscription in Hebrew, Yiddish and Lithuanian, as well as a mass grave marker near the road.

(click photos to enlarge)

Mass grave marker

(wide view)

Memorial at Pajuostė (Payost) near Panevėžys (Ponevezh) (view map)

Shmuel Feifert

(full view)

After the war, during the Soviet rule, a monument on the mass graves [in Pajuostė] was erected and on it a Magen-David was placed. This was one of the unique monuments in Lithuania with this symbol on it. The initiator of this monument was Shmuel (Samuel) Feifert (photo) from Trashkun. During the war he served in the Lithuanian Division of the Red Army, and after returning to Lithuania he devoted himself to the construction of this monument and to getting back Jewish children who were hidden by Lithuanian families and handing them over to Jewish families who were ready to accept them. In 1948, while looking for a Jewish child in Riteve (Rietavas), he was murdered by Lithuanians.

— Dr. Saul Isroff, Panevėžys City & County, International Jewish Cemetery Project

(click photos to enlarge)

Gathering at the Pajuostė (Payost) memorial in 1963, in remembrance of the Jews from Panevėžys (Ponevezh), Troškūnai (Trashkun), and other surrounding towns, who were killed here in August 1941.

Photo by Berl Glezer, 1963. (click to enlarge)

Trashkuners at Payost in 1959 (enlarge and see key)

Trashkuners at Payost in 1961 (enlarge and see key)