My Shtetele Trashkun

by Berl Glezer (1905-1991)

Part II

« back to Part I

Berl Glezer

During World War I many Jewish families from our shtetl Trashkun were evacuated deep into Russia.[NOTE]In 1915, Lithuanian Jews living in areas occupied by the Germans were suspected by the Russian High Command of spying for the Germans and other treachery, and they were expelled to central Russian provinces or Siberia under brutal conditions. The journey was very difficult, and when people arrived they lived in crowded soldiers' barracks. Illnesses spread and many people died, although no one from our shtetl. Food was provided [by Jewish aid societies], and people without shoes were given material to make them.

After the war, people began to think about moving back home. People thought that if they returned to Trashkun the sun would shine more brightly there and it would be easier to make a brighter and nicer life. The trip home was also very difficult and people returned from the long journey exhausted and sick. Other than Yoshe Saltuper the feldsher [unofficial medical practitioner], little medical help was available and there were few remedies and medicines. Even with only a few, Yoshe was able to help people. The Trashkuners who had not been evacuated were back on their feet by then, with food supplies and cellars full of potatoes. Some of the hungry returnees to Trashkun demanded that the well-off people share their stored food with the families who had nothing. When that did not happen, people tore the locks off the doors of the storehouses and distributed the potatoes among the poor.

Trashkuner youth (click to enlarge and see key)

Two or three years later as people were beginning to recover, they began to think about improving their lives. People found work, earned fairly well, and lived in separate apartments. There was money for marriages. Young and old glimpsed a better life. A Jewish school opened where the children studied Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, mathematics, and singing. Since the school was too small for all the children, two shifts were arranged. Teachers came who helped to organize the shtetl youth, and the townspeople often gathered to hear lectures. I think the first teacher was Leybson, and there were many more, including Urbanovich, Zak, Leyklo, Sheskint, and others. A drama circle was organized that put on frequent productions. Instead of admission tickets, the audience donated clothing for poor children. The Zionist movement became active in the shtetl, and money was collected for the Jewish National Fund and the United Israel Appeal. However, Jewish schools were not open for long. They closed at the time of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Looking for a Better Life

The economic situation was very bad and many young people wanted to acquire a permit for immigrating to Palestine. Many went to learn at the hakshore.[NOTE]hakshore: agricultural training for Palestine No one was afraid of the work, but our parents were opposed to their children going so far from home to become farmers. The chalutzim (pioneers) were Chaim-Lipke and Mottele, sons of Rayna [Nurkin]; Beylka daughter of Nochum [Chaimovich]; Chashka daughter of Dobra [Kushner]; Rochka daughter of Paya [Rutenberg]; Binyomke son of Eleber [Zalk]; Ziske son of Sora-Tzipa [Voskoboynik]; Bunka daughter of Yisroel [Beyner]; Yisrolkele son of Shimen [Glezer]; Avremke son of Shleyme [Kovnovich]; Peska daughter of Ayzik [Kozhenetz]; Shmulke son of Chaya-Bashl; and Chayka daughter of Binyomin [Krasovsky]. They went to Palestine, lived on a kibbutz, worked hard, and were happy. Leybke son of Eleber [Zalk] went to Palestine and later returned to Trashkun to fetch Nechomka daughter of Avrom [Puner], to marry her. Botzke son of Ortzik [Glezer] and Avremke son of Bertzik [Yuzent] went later. When Israel was an independent state, they took part in defending the land from Arab attacks.

[ Troskunai residents who applied for immigration to Palestine ]

Trashkun chalutzim, 26 April 1930 (click for full view & key)

Trashkun chalutzim, 1930 (click for larger photo & key)

In those years other young people emigrated to seek a better life in other countries, among them: Itzke son of Henech; Berke son of Chaye-Sore [Konkurovich]; Itzke-Chaim son of Sore-Gite [Vinik]; Meyshke son of Bentze [Segal?]; Shike and Khonke, sons of Ayzik [Kozhenetz]; Moneske son of Gershon [Solomon]; a son of Avrom-Itze the smith; a son of Nochum [Chaimovich]; and a son and daughter of Nochman [Lichtin] son of Pesha. Some went to Africa, some to America, and some to Brazil. Also Bentzke son of Leyzer [Karpov], brother of Moyshke son of Leyzer, left and then the entire family left. Moyshe-Itzik and Hirshl, sons of Leybe [Shepshelevich] the shammas, went to Brazil with their families, and so did Nechomka daughter of Buna-Rele. Zavl Martsushky and his wife Freydl daughter of Henech [Vinik] went to Brazil but he didn't like it there and they came back.

From all the names it is evident how many young people left our shtetl Trashkun, but those who remained did not sit with idle hands. They did all they could to make life nicer and better. People bought many books, and the library had about 600 in all. The library was located at one time in Nochman [Lichtin]'s house, and next in Shneyer's house. Thursday was the day for requesting books. The storekeepers and merchants improved their businesses and the handicraft workers expanded their ventures. It was a time of prosperous revival of the standard of living. The Jewish folksbank [Jewish community bank] functioned and disbursed money in installments to everyone who needed it.

Lithuanian Nationalism

Yet the revival of prosperity did not last long. The Lithuanians organized a movement with the goal of preventing Jews from doing business. They created Lithuanian cooperatives where the merchandise could be bought more cheaply than at the Jewish market stalls. The Lithuanians also bought products from farmers at better prices than the Jewish merchants could. They tried to prepare Lithuanian handicraft workers to compete with the Jews, but did not succeed because the Lithuanians were unable to make a suit such as Binyomin [Krasovsky] the tailor could sew, or shoes such as our shoemakers could make. When it came to our bricklayers and carpenters, the Lithuanians could not even think of competing. And when it came to furniture, the Lithuanians took a long time trying to learn how to make cupboards, beds and chairs with the master craftsmanship of our craftsmen. Their slogan was “Lithuania for Lithuanians” and they were supported by the ruling authorities. The Jewish population did not have equal rights and they began to feel that only under Soviet rule would all peoples be treated fairly.

Soviet Rule

In 1940 Soviet rule came to Lithuania.[NOTE]Lithuania had been an independent state from 1918 to 1939, between the two wars. When Red Army tanks drove through our shtetl, we Jews applauded the tanks and threw flowers. At the time we thought this was the most powerful army in the world and could easily protect humanity from injustice. Meanwhile Lithuanians who belonged to the fascist party were telling us we would cry, because they knew that the Germans would triumph and kill the Jewish people.

The local representatives of Soviet rule in our shtetl were Elke son of Shleyme [Kushner], who could barely sign his name in Lithuanian; Hirshke son of Libetzke; Shmulke son of Shleyme [Kovnovich], the only one who was literate; and Lithuanian youths completely lacking the experience necessary to take the new rule into their hands. A young Jewish man, a Communist who had been in jail for six years for illegal political work, was sent to Trashkun from Ponevezh (Panevėžys). He was supposed to teach the young people how to become leaders in the new Soviet order.

People found no peace under Soviet rule. The justice in which they believed so strongly did not come about; instead the situation became even worse. The Jewish folksbank was closed. Jewish schools were closed. Businesses were empty. People were driven out of their houses, including Hoda and her daughter Esther; Beyla-Noyma; Avrom son of Mordche; and in addition, some Lithuanians. People demanded justice from the young Jewish communist who had come from Ponevezh. In a circle consisting only of Jews, which I belonged to, he told us that if he had known how the Soviet order would turn out, he would not have spent that time in jail.

It was difficult for the leaders of the new Soviet order to calm the unhappy population. They set about finding people who could help them, but found few, so they began to organize young Komsomol [Communist Youth Union] members, or komsomolists, as they called themselves, who mainly were Jewish youths who had joined against their parents' wishes. Who were they? Noske and Tevke sons of Tzipa-Hoda [Klatzko]; Sorka and Neyachke, daughter and son of Nochum [Chaimovich]; Muska and Chanka daughters of Shleyme [Kushner]; Zeldka daughter of Nosn [Yuzent]; Beyla-Rochka daughter of Binyomin [Krasovsky]; Lozerke son of Tamara [Lichtenstein]; Henechke son of Freydl [Martsushky]; Moyshe-Fayvke [Pevzner] grandson of Chava-Ester [Solomon]; the two sons of Yoshe son of Gershon; Fishl [Levin]'s two sons; and about a dozen more people.

The komsomolists were sent to the villages to help the farmers carry out various tasks in the fields, but the farmers did not need their help and conflicts arose. Jewish komsomolists were deliberately sent to work on the Sabbath, which increased the unhappiness of their parents. A large number of injustices were forced on the population against their will. Then in the autumn people were ordered to go and vote when an election was held for a new assembly. But these events were short-lived because even bigger events were about to take place.

World War II

World War II began [in the Soviet Union] on 22 June 1941, and the first artillery shots came very close to us. On Monday [23 June], here is what happened: the capable working people of the shtetl were sent to help finish building the airport that was located not far from a Jewish cemetery. It was a very hot day and a lot of people were half-naked because of the hard physical labor, when suddenly three black German planes appeared, followed by explosions of falling bombs. The people working there all ran home. On that same day some people from Ponevezh had already come to Trashkun so as not to fall into the hands of the fascists, who were taking vengeance on the Jews there. The Jewish population in Trashkun was very uneasy, but no one could decide what to do. One thing they knew, the komsomol youth must leave the shtetl as quickly as possible, along with any adults implicated in supporting the Soviet order.

Tuesday morning [24 June], Elke son of Shleyme [Kushner], together with a Lithuanian co-worker who was also a good friend, left on bicycles. The Lithuanian shot Elke along the way. (See Shmuel Kovnovich's more detailed account of this incident.) Tuesday morning Nosn son of Bertzik packed up two wagons with the few goods that remained in his market stall and left to go to his parents in Ponevezh. This was hard to understand, since other people were running away from Ponevezh while he was running straight there with his wife and small children. But this decision didn't seem foolish to him because his head was spinning, and the other Jews of the shtetl were in the same condition.

I had a Marconi radio. Broadcasts were made from Kovno (Kaunas) [NOTE]Kovno was occupied by the Germans on Tuesday, 24 June 1941. calling upon the population to shoot Jews and Red Army soldiers. Moscow Radio announced that the Germans had attacked and declared success, but that they would immediately be driven back. Many people believed the Moscow Radio announcement because they thought that the Red Army was stronger than the Germans.

By Wednesday morning [25 June], the komsomol youths had already arranged to take the train that ran through Aniksht (Anykščiai) and Svintsionele (Švenčionėliai). Their parents had prepared a small bundle for each of them to take along. The parents hoped to leave too if they were lucky. These youths left that same night on their own harnessed horses, and in fact they did survive.

Leyzer son of Leah-Toyba [Klatzko], and Shleyme [Kushner] the butcher loaded part of their bundled belongings into Shleyme's wagon, where Shleyme's wife Dobra was seated along with his daughter Dverka and her husband [Leyb Slavinsky] and child. The remaining bundles were put into Leyzer's wagon with our two bundles. In Leyzer-Moyshe's wagon were only Leyzer himself and his wife Tzipa-Hoda. My wife Frida [née Kozhenetz] and I followed the wagons, walking our bicycles. Moshke son of Bashl, Chanka daughter of Dobra, and her younger brother came along with us, also walking their bicycles.

When we arrived at the place in the road between Trashkun and Aniksht (Anykščiai) where the train always stops for a minute, we saw someone on a bicycle riding toward us from the direction of Aniksht. It was a Lithuanian, a good acquaintance of mine, who asked where we were going. I told him that we were headed toward Aniksht. He told us that no Jews were being allowed through Aniksht At that moment I saw the train coming that makes a short stop at that spot. We all started to run, managed to get on the train, and traveled on, but we weren't allowed to bring our bicycles with us. Yisrolkele son of Shleyme [Kushner] had loaded his bicycle in his wagon, but when he and his family finally arrived by wagon at Aniksht, they were turned around and forced to return to Trashkun. The Lithuanian fascists took all the belongings out of the wagons and kept them.

Berl Glezer's escape route out of Lithuania

Meanwhile we went by train in the direction of Little Svintsyan (Švenčionėliai). From there we tried to decide whether we should go to Vilna (Vilnius), where Bunka [Kozhenetz, Frida's sister] lived and worked. After we had traveled several kilometers from the Trumbatishki station, the Shaulists[NOTE]Shaulists: Lithuanian collaborators with the Nazis. stopped the train and entered the cars. Some armed Red Army soldiers happened to be seated there and the Lithuanians tried to take their guns, but fortunately the soldiers did not give them up. There was some shooting, which did not turn into anything good. Some of our komsomol youths were wounded from the shooting and had to return to Trashkun.

We arrived in Little Svintsyan. There were no Jews there. The railway line had already been bombed, so going to Vilna was out of the question. We entered the synagogue and thought about spending the night there, but the local fascists warned us that if we didn't leave the synagogue, they would set it on fire with us inside. They also stopped some women with children whose husbands had been shot, as well as two young men from Kovno. We left the synagogue and went on foot because the trains went no farther. Tzipa-Hoda [Klatzko] and her sons Noske and Tevke, Libetzke and her son, and Moshke son of Bashl and his wife, did not come with us but had to return to Trashkun. The first Trashkuners shot that day were Noske and Tevke [Klatzko], and Ruvke and Hirshke sons of Velve [Itzikovich]. [See Itzhak Konkurovich's more detailed account of this shooting.]

When we had gone about a kilometer from Little Svintsyan, some Lithuanian collaborators armed with rifles crawled out of the ditches along the side of the road. They said that if we wanted to go any farther, we would have to give them everything we had, otherwise we would have to turn back. They also threatened to shoot us. We gave them everything we had and walked on. The women who had children with them did not give up their belongings, so they were turned back.

While continuing in the direction of Big Svintsyan (Švenčionys), we noticed three Lithuanians on bicycles and thought they were pursuing us. Shmulke [Kovnovich] and Moyshe Arken ran in fear into the forest, and kept running until they fell from exhaustion. The Lithuanians passed by. They were peaceful citizens. We arrived in Big Svintsyan very late at night and stopped at a synagogue there. We were very tired but our eyes would not close. Every rustle we heard outside seemed to threaten danger, but it was only Red Army soldiers passing by. Suddenly Shmulke and Moyshe Arken walked into the synagogue! It was a joy to be all together again. Then through the window we saw a larger group of Red Army soldiers and went out to ask them to take us with them. We had just about succeeded in persuading them when a still larger Red Army detachment joined them, and the smaller one did not take us along.

We walked in the direction of the town of Polotsk (Polatsk) under a hail of bullets and bombs. The girls' feet were sore and they could go no farther. Soldiers in a passing Red Army car noticed and took the girls with them. Shmulke's feet were blistered and he could go no farther, so they took him along too. The rest of us dragged ourselves on to spend the night in the forest. Some Red Army soldiers saw us there and accused us of being spies. They searched us, and finding nothing suspicious, told us not to panic but to turn around and go home. Then they found money in Lozerke [Lichtenstein]'s trousers. They asked where he worked and he said in a bank in Ponevezh. They accused him of helping to rob the bank and getting away before he was caught. They arrested him and took him with them. We went farther, very hungry.

We walked about 300 kilometers and finally reached Polotsk. The city was under continous bombardment. It grew worse and we ran to hide in cellars. Near evening we learned that a train was about to leave the station. We rushed to the train and got into one of the cars. At that very moment a bomb fell near the train, and the train could barely move. Repairs were made to the train and we departed. Ours was the only train to cross the bridge. Later the bridge broke in half.

The days were very hot. We traveled as far as Tambov in open cars and were injured by the hail of burning coal chunks flying from the locomotive. After arriving at Tambov, we were sent to a kolkhoz (collective farm) called Umyot. As soon as we arrived, we jumped into the river. It had been a long time since we had had a chance to wash off the dust.

We were accepted well by the kolkhoz, given food to eat, and sent into the fields to work. I was part of a team of workers who repaired agricultural machines. Because I did a good job, two liters of flour were added to my daily rations. Lithuanian citizens were not accepted into the Soviet army, but on the first of September 1941, I was drafted along with a lot of other people who had been evacuated. Those of us able to carry out the work directly were sent to the front. When our train arrived at the designated location deep in the Ukraine, German airplanes immediately appeared overhead and dropped a lot of bombs. All the train cars caught fire and very few people survived. I was among those who came out alive.

Berl Glezer's route from Lithuania, through Belarus into Russia, a harrowing trip to the front in Ukraine, back to Russia, and finally into Siberia. While in Yurga, he discovered that his niece and other young women from Trashkun were in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

The officer who had brought us there sent us back where we had come from. The return trip was no easier. Arriving at the kolkhoz, I learned that one of my relatives by marriage was in Penza, where he had been living since being exiled during World War I. I wanted to find out from him whether my sister Dobl and her family had gone to live with him, but I didn't know his address, so I wrote to the Penza administration asking about my relative-by-marriage. Chaim-Itzik was his name, Katz was his last name. When they received my letter, they took it directly to Chaim-Itzik himself.

At that time, Chayka daughter of Hinda [Kozhenetz], who had arrived just a few weeks earlier, was staying with Chaim-Itzik. As soon as she saw my letter she wrote a reply, but by the time her letter arrived at the kolkhoz, I had been drafted. I found Chayka's letter when I returned. Frida told me that after my departure the kolkhoz had given her very hard work, so I decided that we would not stay in this kolkhoz. We decided to move to Penza, but what could we do? We had no money and no train tickets. I went to the nearby station and saw a lot of railroad cars standing there, filled with Jews who were being evacuated farther eastward. Their destination was Penza.

Quickly I went back to the kolkhoz and told the head of the kolkhoz that we were leaving. He gave us fabric for a shirt for me and a dress for Frida. Nochke could not come with us yet because he had taken his father's work assignment with the head of the kolkhoz, so we left. Several days later Nochke also arrived in Penza. He had friends there who registered him for work in a military factory, and he stayed and worked there until the end of the war.

We discovered that very good accommodations were available in Penza, but that meant little to us because we weren't registered in Penza. While there, I learned that my sister Dobl and her family were living in the Siberian town Yurga. We didn't have enough money to travel there, but Reyzka daughter of Rochka gave us 200 rubles to help us pay for the trip. Moyshe-Fayvke [Pevzner] and Henochke [Martsusky] volunteered for the army, and it is very likely that they were killed at the front because I heard no more about them. When we arrived in Yurga where my sister Dobl was living, I was drafted again and was supposed to leave in two days, but where I would be sent, no one knew. There I learned that Lozerke [Lichtenstein] had been killed at the front in the Lithuanian Division.

While we were waiting for the orders that would inform us when we would leave, an officer from a military factory that had been built in town came to see us draftees. He asked which of us were workers and I among others raised my hand. He said to me, “Come on, I'll take you.” I answered, “But there is a war on. How can I go with you?” He accepted me into his factory.[NOTE]Since it was a military factory, it was considered part of the war effort. I was not released from working there until 1946. While there, I asked a lot of people from big cities whether they knew of my niece Zelda [Yuzent]. I received the same answer from everyone, that she was not there.

One day an acquaintance told me that a friend of his had arrived from Tashkent, a city in Siberia,[NOTE]The term "Siberia" was often used loosely to refer to "the East." Tashkent is actually in Uzbekistan. and that his friend had met Zeldka there. Right away I found out her address and told her to come. She arrived but still had an illness in her bones and was very sick. She rested a little. I found work and began a good, a real job. Zeldka stayed with us when we all returned to Lithuania together. Then she traveled to an aunt who had settled in Birobidzhan, where she married one of her aunt's sons. She lives there today and married off two sons there.

Through Zeldka I found out about the rest of our girls from Trashkun, then living in Tashkent. While working in the factory, I came across a Lithuanian newspaper and read there about Sorka daughter of Buna-Rele, who had received recognition as one of the best workers in the city. I wrote to her and she replied that she was living in great poverty, it was cold, and that she didn't have enough money to buy warm shoes. She was unmarried then. Even though I was not earning very much either, I sent her 200 rubles to buy shoes. Evidently she quickly forgot about this. They returned to Lithuania from Russia a lot sooner than we did, and by the time we arrived they were already settled in good accommodations with good jobs. We stopped to see them with our two-year-old child upon returning to Vilna. They gave us such a small corner that we could not stay there long, and had to find a better place.

Rivka daughter of Binyomin [Krasovsky] found out about our situation and offered us a small room in her apartment. We lived there until we found our own apartment and decent jobs. We went to Trashkun and sold our houses. Then we had a little money and began to help others who returned, who above all needed a place where they could spend a few nights and catch their breath after the war years. We invited the returnees to stay with us in our apartment. So it happened that Khone and Muska, daughter of Dobka, lived with us for a while until they got married. Also Shmulke son of Shleyme [Kovnovich] lived with us until he got married. After their marriage we helped them manage to make ends meet.

After the War

When we surviving Trashkuners did not find any of our loved ones on returning from Russia, we settled in Vilna or Kovno. We found work and apartments. Those who weren't married got married. We all got together often and sometimes we traveled together to Ponevezh and Trashkun, still looking for relatives.

Vilnius, 1962. (click for key) Surviving Trashkuners gather with their spouses and children to celebrate a visit of Neyach Chaimovich's sister Beylka from a kibbutz in Israel. See another photo of survivors at the same occasion.

Much later all the surviving Trashkuners emigrated to Israel. Frida and I were the last to arrive there. I always longed to be reunited with the other Trashkuners. My greatest joy was when this longing was fulfilled. Unfortunately, I did not find all of them among the living. I didn't find Motke or Chaim-Lipke the Nurkin brothers, Avremke or Shmulke sons of Shleyme [Kovnovich], Botske or Rozka [Glezer], Beylka daughter of Nochum [Chaimovich], or Itzke son of Chaya-Sora [Konkurovich]. Some Trashkuners I visited only a few times, and others I didn't see even once. I kept in contact with others by telephone.

Reunion of Trashkuners in Tel-Aviv in 1987, three years before the author Berl Glezer and his wife Frida emigrated to Israel. (click for key & second photo)

Before leaving for Israel I went to Ponevezh and Trashkun to take leave of my dear ones who had been murdered and the terrible deeds concealed.

| At the Mass Graves in Ponevezh | |

| I see you here, my sister, your husband, your beautiful children, in the third mass grave. The war found us right away. I thought I was refraining from sin then. The artillery came closer And I felt the Germans on all sides. No one in the shtetl slept that night but no one left, no one ran away. Why didn't I say words of warning— “Harness the horses to the carts, go away, Go somewhere, anywhere, away!” Where was my head? Was I out of my senses? |

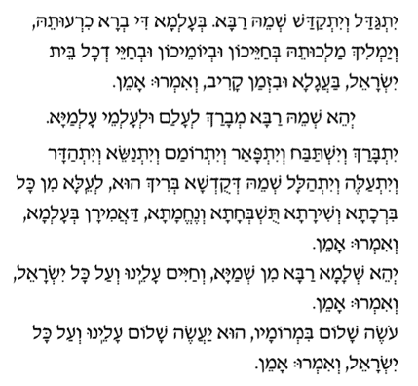

To this day I cannot forgive myself. The great tragedy is before my eyes always. Now, as I barely manage to say goodbye to you at the mass grave, I recall your words of farewell. You said there will be a miracle and we will see each other again. There was no miracle. With a broken heart I stand beside the grave of you and your husband and your beloved children. Yitgadal v'yitkadash sh'mey raba . . . —Berl Glezer |

Glorified and sanctified be God's great name throughout the world which He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom in your lifetime and during your days, and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon; and say, Amen.

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity.

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He, beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that are ever spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and life, for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

He who creates peace in His celestial heights, may He create peace for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

✡︎ Yizkor Date for Trashkun: 23 August 1941 • 30 Av 5701 • ל׳ בּאב תש״א

▶ Return to Part I