-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Mlynov and Mervits in the Russian Period (1793–1918)

***

Contents

Background | Early Response under Catherine the Great (1792–1825) | Tzar Nicholas I and Conscription (1825–1855) | Improved Conditions Under Tzar Alexander II (1855–1881) | The Fallout of Alexander II's Assasination (1881–1894) | Life Under Nicholas II (1894–1917) | First Wave of Emigration to America (1881–1910)

What were Mlynov (Mlinov) and Mervits (Muravica) like in 1850 and 1858?

Russian records called "revision lists" in 1850 and 1858 have been located and translated for Mlynov and Mervits. These records provide a window into these towns' populations, the structure of the households, ages, gender, mortality rates and pressures of conscription on those residents.

Mlynov: 1850 Revision List (census) in Mlynov and 1858 Revision List (census) in Mlynov

Mervits: 1850 Revision List (census) in Mervits and 1858 Revision List (census) in Mervits

Background on the Russian Period

The names of Mlynov and Mervits ancestors that have come down to us, via photos and oral traditions, lived in these towns after they were incorporated into Russia in the Second Partition of Poland in 1793. At this time, Russia acquired the Volhynian Voivodeship, which had been the administrative area of which Mlynov was part, first in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1566 until 1569, and then under the Polish Crown within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from the 1569 Union of Lublin.

The First Partition of Poland had been twenty years earlier in 1772. But following internal political division and strife in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Empress Catherine the Great was invited in to the Commonwealth to support conservative forces. A short war followed and a treaty resulted, in which Russian acquired vast new territories that included Mlynov and Mervits.[1]

Overview

It is useful to distinguish several broad periods of Russian rule:

(1792–1825) Early Response under Empress Catherine and Tsar Alexander I

To date, we do not have oral or written traditions of any Jewish ancestors who lived in Mlynov or Mervits during this first period of Russian rule. This was a time when Russian officials were formulating broad tenents about how the Jewish populations should be governed and how Jews might be improved and transformed, principles that would be more forcefully implemented under the rule of Tsar Nicholas I.

The Jews were seen as a harmful element that disrupted relationships between landlords and peasants requiring steps needed to be taken to limit their impact. Tsarist officials believed the deleterious impact of Jews was fed by what they regarded as fantatical religious beliefs. Influenced by Enlightenment ideas, however, officials believed the faults of the Jews were not innate but the consequence of their unfortunate history.

The Jews could be changed and improved and policies were implemented that they thought would improve the population. Of course, what constitutes improvement is in the eye of the beholder. The ideas of this period laid the groundwork for the next, which saw a more rigorous and at times brutal implementation under Tsar Nicholas I.[2]

Read more....(1825–1855) Reign of Tsar Nicholas I

We do have a handful of ancestors' names from this period of Russian rule, which is generally viewed as a more ruthless and difficult period for Jews. Nicholas I regarded the Jews as a harmful alien group that should be completely assimilated within the Russian people. To achieve this goal, he adopted numerous policies especially the infamous compulsory military service for the Jews in 1827. This was accompanied by quotas and the seizure of Jewish children, who were to be educated in Cantonist schools for soldier children in the spirit of the Christian religion. One story of conscription of a Mlynov ancestor belongs to this period.[3] Read more...

(1855–1881) Reign of Tsar Alexander II

Descendants recall the names of many grandparents and great-grandparents from Mlynov and Mervits who lived in this period under the rule of Alexander II, who is remembered more favorably than his father. Tsar Alexander implemented a number of favorable reforms; the most significant was emancipation of Russia's serfs in 1861, which had significant repercussions for Russian policy towards the Jews.

Alexander's reign was a more hopeful one, with greater economic and educational opportunities and more rights than previously, though the overarching goal was still the acculturation of the Jews. Between 1850 and 1900, the Jewish population in Russia increased substantially due to a higher birthrate and low mortality rate. In 1850, the number of Jews in Russia stood at around 2.35 m and almost doubled to 5 m by the late 19th century. This population pressure created economic hardship for the emancipated serfs and the Jews who were viewed as competition.[4]Read more...

(1891–1905) Reign of Alexander III and son Nicholas II

We know a great deal more about the individuals born in Mlynov and Mervits in this period because many of them and their families migrated to the United States, and Baltimore in particular, and have left us photos and oral traditions. The assasination of Alexander II in 1881 triggered a period of retrenchment under his son Alexander III (who ruled 1891–1894), and grandson Nicholas II (ruled 1894–1917), and began with a series of pogroms in 1881 and 1882 that helped trigger a massive immigration to the United States.

Though these pogroms did not reach Mlynov, the first pioneers to Baltimore left Mlynov in the wake of Alexander's assassination and the Mlynov migration to the US and Baltimore in particular increased throughout this period up until WWI. The pogroms, and growing pessimism about the possibility of ultimate acceptance as equal citizens in Russia, provided the foundation for an initially small but growing Zionist movement during this period as well. The first Russian revolution in 1905, which apparently reached as far as Mlynov, arguably lay the foundation for the later revolution of 1917.[5]Read more...

***

The Early Response to Jewish Distinctiveness

It was an inauspicious time for Jews who were living in the Volyhnian area who now came under Russian rule. Much would change for Jews in this period which extended from 1793 to the outbreak of WWI in 1914 and the Revolution in 1917. Until this point, Russia had never had a substantial Jewish population and thus did not yet have a clear administrative policy on how to engage this ethnic and religious population that, in the eyes of its rulers and populace, needed substantial reform. The various and often differing attempts to manage this unique population constitute the stuff of Russian Jewish history, which is both fascinating and disturbing at the same time.

The perception that Jews posed an administrative and cultural problem stemmed from longstanding perceptions that “the religious teachings of the Talmud preserved their isolation and sense of superiority," and that "the kahal [Jewish town governance] acted as a sort of dictatorship within the Jewish community" which prevented change. The distinctiveness was reinforced by the "special dress which the Jews wore" which underlined their separateness from the rest of the population”. The Jews also had specialized in various economic sectors which had been open to them, such as the liquor trade, for example, which exacerbated the perception that the Jewish community needed to be reformed.[6]

Nonetheless, the winds of change were also on the horizon. The French Revolution, which had started only a few years before in 1789, would, over the course of the next century, bring new views of rights and emancipation first to Jews in Western Europe and eventually to those in Eastern Europe too. The way that France and other Western Countries incorporated Jews into their cultures partially inspired Russian policy makers during the course of the century. These impulses lay in the future for Russia but by the end of the 19th century their influences were apparently reaching even those who lived in Mlynov and Mervits, along with other impulses such as Hasidism, Haskalah (enlightenment), even as the early precursors of Zionism like Leo Pinsker were starting to become skeptical about the possibility of Jews ever being accepted in the nations they were living.[7]

The history of the century for the Jews as a people under Russian rule is thus complex and multi-faceted and one can only speculate how these trends might have impacted those living in Mlynov and Muravitz from hints in later oral traditions from descendants of families living there, and from the now translated Mlynov census (Revision List) of 1850. It seems likely that some of the first Mlynov and Mervits ancestors we know about, were born late in the reign of Tsar Nicholas I who reigned as emperor from 1825–1855. It would have been their parents and grandparents, whose names we do not have, who experienced the earlier transition to Russian rule under Catherine the Great and Alexander I (1801–1825), if these families had already been in Mlynov at the time. In that period, a variety of new rules were formulated which combined “Enlightenment-derived ideas for the transformation of the Jews with the now traditional Russian preoccupation with the need to limit their harmful impact on the peasantry of the areas acquired fromm Poland-Lithuania…”[8]

This was a range of complex, not always consistent, policies developed to transform the seeming backwardness of the Jews, including: restricting their economic life, particularly their involvement in the liquor trade, which was a common means of earning a living, barring Jews from inn-keeping and agriculture, and implementing an expulsion of Jews from the countryside.

For the most part these new rules were largely not implemented though they provided the framework and tenents that were to dominate under Alexander’s successor Nicholas I (1825-1855) under whose rule conditions worsened. Nicholas saw the Jews as an “anarchic, cowardly, parasitic people, damned perpetually because of their deicide and heresy. They were best dealt with by repression, persecution, and if possible, conversion.”[9] It was under his rule that the Pale of Settlement borders were formally legislated.

***

On Conscription of Jews Under Tsar Nicholas I (1825–1855)

One of the most notorious policies implemented by Tsar Nicholas was the imposition of military conscription on the Jews.[10] While in other countries earlier, conscription was welcomed by Jews and seen as a way of demonstrating their citizenship in a universal draft, in Russia it was a burden imposed by government for economic reasons. Nicholas was a believer in the army as a school for virtue and he believed the ills of Jewish society could be cured by forming its young men into the army. The parents of those ancestors we know about may have been subject to the quota of 4-8 recruits per every 1,000 adults. Since the Mlynov and Mervits population was well under that number, we do not know how many recruits if any were taken from the town.

Jewish boys and men were inducted into the army between the ages of 12–25 and sometimes served for twenty-five years in special "cantonist" battalions. Often recruits were taken from boys who were much younger. Under Nicholas' reign, about 7,000 Jews served in the Russian Army (approx. 4–6 percent). Recruits were not allowed to observe religious practices or visit with Jewish families, and conversion was openly encouraged.

The conscription policy was particularly painful because Jewish Kehilla leadership was involved in identifying the recruits and, at the government’s encouragement, selected those from the weakest and most defenseless sections of the community. Leadership often had to hire special officials “khappers” (grabbers) to enforce the draft.[11]

We know now from the 1850 Revision List (census) in Mlynov that a number of young men were recruited during this period and a number fled town to avoid conscription.

***

The Conscription of Mordechai Rivitz

From the oral traditions that have come down to us from Mlynov descendants, we have at least one recorded family memory from this particular period that suggests how mandatory conscription touched the lives of those living in Mlynov. The story concerns the conscription of Mordechai Rivitz, the father of David Rivitz and Ida (Rivitz) Fax. Both David and Ida, born circa 1867, will play important roles in our story in the next generation as they led the way in the Baltimore migration. David married Pesse (Bessie) Demb, the oldest of the Demb daughters. David and Bessie's youngest daughter, Clara Fram, wrote her memoire in 1982 in Baltimore, nearly seventy years after she left Mlynov.[12] She recalls the family oral tradition about her grandfather Mordechai and his conscription experience. Clara writes:

My grandfather, Mordechai Rivitz, who died when I was 18 months old [circa 1903–04], nine months after my father left Malynow the last time, had been 7 years old when he was snatched up by the Czar's agents and conscripted into the Russian army for 25 years' duty. His parents, were, of course, mortified to think of what would become of him, this young child. Either he would die in the army or they would convert him. So his father journeyed to one well-known Rebbe (a Chassidic Rabbi) for advice and comfort: and he was told that the Lord would protect his child. At the same time he gave him a book, a "Tehillim" (the Book of Psalms) which the young soldier was to keep with him at all times and study it. The Rebbe inscribed it with the young soldier's full name in Hebrew, of course.

My grandfather was discharged after having served 15 years instead of 25 years because the Russo-Turkish war had ended. He found himself then in Simphoropl in the Crimea, opposite the Turkish capital, Constantinople. There, at age 22, he met a young Jewish orphan girl, the owner of a wine cellar. He married her, and began making plans to bring her to his home town in the Ukraine. It took them 2 and 1/2 years to get there, during which time their first child was born, a girl. [Clara's Aunt Chaia/Ida Rivitz]. On arriving home, their son David, my father, was born.[13]

Clara's memory or reconstruction suggests that her grandfather had been released early because the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) had ended early. I suspect that Clara made a mistake in this recollection and that he was in fact involved in the Crimean War (1853–56).[14]

***

Stories of Conscription Avoidance

To date, I know of no other stories of conscription that involve individuals who lived in Mlynov or Mervits during the period of Nicholas' reign, which may be a consequence of having little information about that generation of ancestors. However, from later phases of Russian rule, we do have stories of family name changes that are associated with the avoidance of conscription and we have some photos of Mlynov individuals in Russian military uniforms.

For example, the Demb family oral tradition is that Simha Gruber, the oldest son of Israel Jacob and Rivkah (Gruber) Demb, was named Gruber instead of Demb (his mother's maiden name) to avoid the draft.

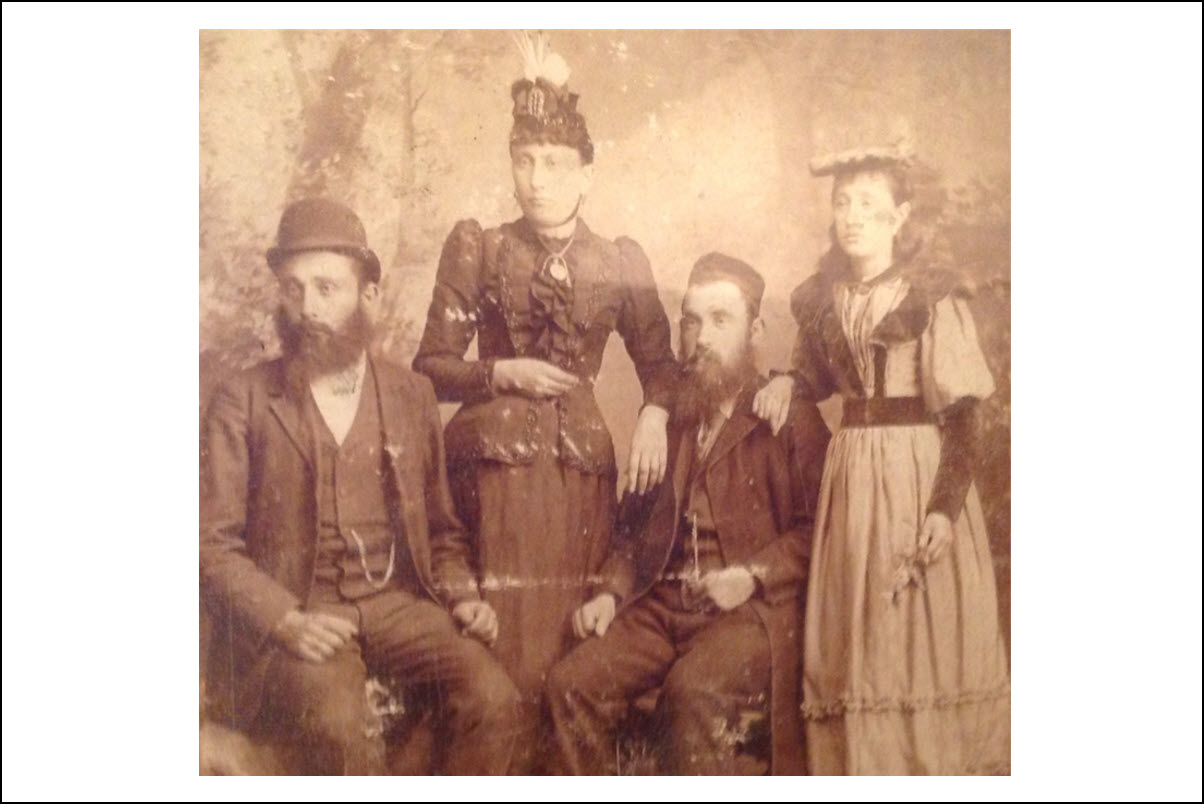

Simha Gruber and second wife Chaya, with son and daughter-in-law, and grandchild. Courtesy of Tamara Kirson

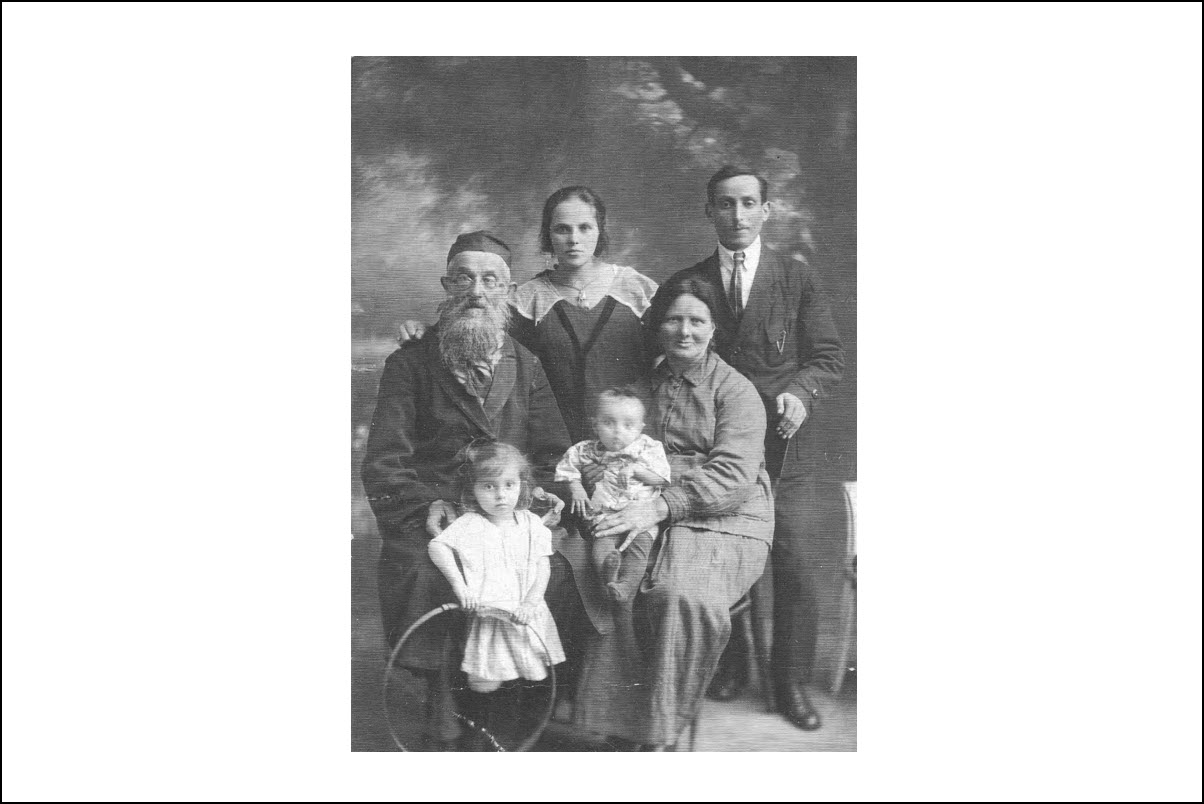

Simha Gruber and second wife Chaya, with son and daughter-in-law, and grandchild. Courtesy of Tamara Kirson Avrum Fritsis, grandfather of Liba Tesler, Memorial Book, 478.

Avrum Fritsis, grandfather of Liba Tesler, Memorial Book, 478.Similarly, according to oral traditions from Tesler descendants, Avrum Fritsis changed his last name to Tesler to avoid the draft in 1868. At the time, Avrum was living in Ostrog a town 50 miles away from Mlynov. His granddaughter, Liba Tesler, recounted the following story:

When Avrum received his draft notice, he began looking for ways to avoid such a fate. After bribing, the right people he managed to obstain the passport of a former conscript who had passed away. This deceased person was named Avrum Tesler. The original Avrum Tesler, or his father, was most likely a carpenter because the Ukrainian word for carpenter is tesler. Avrum assumed his new surname, knowing there was a large element of risk. Many Jews took the same course of action.

Not long after executing this strategy, Avrum Tesler moved to Mlynov, a town where he would not be known by the local authorities.[15]

Another story from a later period after WWI, is told by descendants of the Zutelman (Settleman) family from Mervits. According to his son, Irv Settleman, Frank had a friend who maimed himself by shooting off his toes in order to avoid conscription following WWI. Frank didn't want to go that route and instead left Mlynov for the Buenos Aires where he stayed on his way to the US before eventually making his way to Baltimore in 1923.

Most of the Mlynov ancestors about whom we know more were born in the Russian period under Tsar Alexander II's rule. It is to this period that we now turn.

***

Reign of Tsar Alexander II (1855–1881)

We know quite a few names of Mlynov and Mervits ancestors who were born during the rule of Alexander II. We know about them because a number of them and their children emigrated from Russia to the United States between 1880-1914, after Alexander II was assassinated by revolutionaries.

We can speculate that though Mlynov and Mervits were small villages in the Pale, the residents probably had a favorable and hopeful view of the new Tsar, though that view may have waned over the course of his rule.

The reign of Alexander II is generally regarded as a much more favorable and optimistic period for the Jews, though the policy of Alexander II was still focused on the "merger" of the Jews with the Russian population.[16] But unlike Nicholas II, who principally used repression to transform the Jews, policy makers under Alexander II were influenced by Western enlightenment ideas and some in fact argued that the best way to transform the Jews was to grant civil rights and remove restrictions on the population and allowing them to become like other Russians.

Other policy makers, whose views won out, cautioned that a more gradual incremental approach was best, a policy that has been described as "selective integration".[17] As one source summarizes it, "Russian government policy toward Jews can be understood as the product of an unresolved tension between integration and segregation—a tension that resulted in contradictory laws and regulations, persisting from the days of Catherine the Great (r. 1762–1796) to the fall of on Alexander II."[18] Alexander's policies continued the effort to integrate the Jews into the Russian body politic, but under a far more liberal guise than that of his predecessor. During this period, the Jewish communities thus saw some positive developments: conscription of children was outlawed, Jewish residence outside of the Pale of Settlement was expanded, and economic and educational restrictions against the Jews were lifted.[19]

Specifically, the government did ease restrictions on three groups of Jews who were unlikely to come into conflict with the serfs who were emancipated in 1861. These included the Jewish merchants of the "first guild," the university graduates, the artisans belonging to a guild, as well as retired soldiers.[20] These changes enabled some Jews to settle in the interior of Russia beyond the Pale of Settlement, leading to a Jewish community in St. Petersburg as an example

Local government reforms also gave local Jewish communities greater control over how taxes were spent on schools, public health and roads. The entrance of Jews into the Russian school system, both gynmnasiums and universities, accelerated in the 1870's and an emerging Jewish intelligensia developed in the larger cities that was increasingly Russified and wanted to bring enlightenment to what they perceived to be backward Jewish society. Though the pockets of Maskilim ("enlightened ones") in Russia were small, one of the key leaders of the movement was Isaac Baer Levinsohn, the "Mendelsohn of the East," whose home in Kremenets, only 63 km (1 hour driving today) away from Mlynov, was an important meeting place for those involved in the new movement.[21]

We know that one Mlynov boy, Solomon Mandelkern left Mlynov in 1860 and, after a stint in Hasidism, he later became part of this intelligensia. Mandelkern ended up studying Oriental languages at St. Petersburg University and in 1873, he became assistant rabbi in Odessa, where he was one of the first to deliver sermons in Russian and where he studied law.

While Mandelkern had to leave Mlynov to engage these intellectual trends, we know that some of these intellectual impulses also reached Mlynov by at least the late 1880s. In her memoire, Clara Fram recalls that her grandfather, Israel Jacob Demb , would sit and talk with his son-in-law, Tsodik Shulman, about Tsodik's famous uncle, Kalman Shulman (1819–1899), a maskil and Hebrew writer whose work was significant in the development of modern Hebrew literature. Shulman's nephew married Pearl Malka Demb by at least 1887. Clara writes:

Frequently, our cousin Hertz Shulman, a youth of about seventeen, a student in that school, would stop in our house to study, memorizing his work, while walking back and forth in the room with his book. We knew he was the son of my Aunt Pearl [Pearl Malka (Demb) Shulman] and her distinguished husband [Tsodik Shulman] whom my grandfather [Israel Jacob Demb] was delighted to have marry his second daughter. This man had arrived in Mlynow from Lithuania, well educated, rolling his R’s when he spoke Yiddish; an emancipated, proud Jew, resembling one’s image of Tolstoi, and possessing books in Hebrew and Russian, as well as Yiddish translations of French novels. He also subscribed to a Yiddish newspaper, and would talk to my grandfather about his uncle, the famous Hebrew writer, Kalman Shulman.[22]

Shulman descendants are not clear how Tsodik, ended up in Mlynov and speculate that his stint in the Russian army brought him from Lithuania to the small town off the beaten tracks, where he married Pearl Malka Demb. But perhaps he passed through Mlynov on the way to visit Isaac Baer Levinsohn, the maskil leader in Kremenets. We may never know. In any case, one can imagine Israel Jacob Demb, a student who had himself been brought back to Mlynov from Ludmir by his father-in-law, sitting with his son-in-law, Tsodik Shulman, from Lithuania and talking about the larger trends of Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) that were attracting followers in Russia. Perhaps they also discussed the small boy Solomon Mandelkern who had left Mlynov in 1860 and whose reputation as a "maskil" had grown by this time as well.

Given these positive trends in the period, it is not a surprise that some Jews in this period such as Judah Leib Gordon, one of the famous poets of the era,[23] and even Mlynov-born, Solomon Mandelkern, wrote poems celebrating Alexander II. While there was optimism under the rule of Alexander II, there was also growing impoverishment of the Jewish population in the late 19th century brought on by several factors. The emancipation of the serfs under Alexander created new economic challenges for the Jews who had to adjust to new restrictions intended to protect the peasantry and there was a sizeable increase of the Jewish population from about 1 million in 1800 to over 5.2 million in the census of 1897 which added to the economic challenges of finding work and the growing creation of "luft-menchen," who had no occupation. But in the end, it was the assassination of Alexander II that brought about the critical change that started massive Jewish migration to the United States and gave further impetus to the early forerunners of Zionism.[24]

***

(1881–1894) In the Wake of Alexander II's Assasination / The Reign of Alexander III

We know that the assasination of Alexander II in 1881, and the reversal of his liberalizing policies under his son and successor, Alexander III, had a significant negative impact on families living in Mlynov and Mervits almost immediately. Alexander was hostile to the Jews and his reign witnessed a sharp deterioration in the Jews' economic, social, and political condition. His policy was first implemented by tsarist officials in the "May Laws" of 1882, after a series of pogroms spread across the empire.[25]

In her memoire, Clara Fram tells us that her grandparents, Getzel and Ida Fax (Chaya Rivitz), lost their land and source of income outside Mlynov in the wake of the assasination and had to move back into Mlynov from the countryside. This may have been related to legislation forbidding Jews to own land or live outside towns. In any case, this chain of events is what ultimately led Getzel and and Ida to leave Mlynov and become the first pioneers to immigrate to Baltimore in 1890–91. News about their plans to emigrate must have traveled quickly in the small town of Mlynov. Clara's own father would travel back and forth from Mlynov to Baltimore over the next decade, before moving to Baltimore permanently in 1901, bringing news of life in the new country and providing an ongoing link to the Faxes who had set up shop in that city. Over the next two decades, a number of other Mlynov families followed the Faxes to the US and many of them took up residence with the Faxes initially in Baltimore.

Clara Fram tells the story this way:

Back home with his family [after being released from the military], my grandfather [Mordechai Rivitz] soon bought a small estate they called a Possessia in Irslavitch, utilizing his pension and what my grandmother realized from the sale of her properties in Simphoropl. The children grew up there in the country not far from Mlynow, where the boy David was sent to a Cheder to learn. It was there that he met my mother, a girl two years his senior, the eldest of four beautiful daughters of the town’s scholar [a reference to the four daughters of Israel Jacob Demb and Rebekah Demb]...

As the young family grew, my mother being the eldest of the girls, so did their grandfather’s [Moshe Gruber's] so-called wealth diminish. By the time my father and my mother saw each other in Cheder, though he would have desired a scholarly bridegroom for his beautiful and accomplished Pesse, my grandfather did not object to her marrying into the Rivitz family that was well-off in their Possessia.

In 1880, however, came the Czar’s decree that no Jew could own land. My [paternal] grandfather [Mordechai Rivitz] was forced to sell all his property for whatever he could get, and the family moved into the town Malynow I have already described. His daughter’s husband, Getzel Fuchs [later Fax in Baltimore] left for the new land, America, and a few years later his [Mordechai’s] daughter, Chaia and their child followed [the child was Theresa (Fax) Goodman]. The son, David, my father, left for America at the same time, as he saw that without his father’s “Possessia” he could not make a living.[26]

Clara attributes Getzel and Ida's migration from Mlynov to the events following the assassination of Alexander II, though the assasination took place in 1881, not 1880. Based on available records, it seems possible that Getzel may have left for the US even before the assassination, being an early mover in the migration to the US that would eventually bring two million Russian Jews to the US between 1880 and 1914. If so, Getzel may have been among those who had a growing disallusionment with the hopes that integration and Russification would improve life of Jews in Russia. Getzel's wife Ida apparently joined him in 1891, the same year their daughter Therese was born. Between 1881-86, Getzel and Ida were among 12,856 Jews who left the tsarist empire for the United States. By 1930, a total of 1.75 m had made their way to the US.[27]

Whatever may have motivated Getzel and Ida to leave Mlynov, the period immediately after Alexander II's assasination was a difficult one for Jewish communities across the Russian empire. Within six weeks of Alexander II's assassination, a pogrom broke out in Elizavetgrad in the south. It was followed by others in Kiev and Odessa and soon thereafter the rioting spread to the countryside. Of the 259 pogroms which took place, 219 took place in villages and 36 in cities and small towns. These pogroms were shocking to those among the Russian Jewish communities who had embraced the strategy of acculturation as the path to modernity, and to the Russian government officials, who worried about the connection of the violence to revolutionary impulses among the poorer parts of the empire.[28]

While the violence did not reach Mlynov, nor the nearby towns of Dubno, Rivne, and Lutsk, it is likely that the residents of Mlynov and Mervits, like others in the empire, were worried by what was the worst anti-Jewish violence in Europe in over a hundred years.[29] Most of the pogroms were in other Gubernia (jurisdictions), especially in the south, but there were a few in the province of Volynia, near Starokonstantinov, about 190 km from Mlynov or 2.5 hours driving time today.

The residents of Mlynov and Mervits likely would not have felt much better knowing that the violence was largely spontaneous in character and a result of the growing stratificaiton in the countryside following the abolishment of serfdom. Though the government apparently did not promote the pogroms, some officials subsequently blamed them on the economic oppression of the peasantry by Jewish money lenders and tavern keepers, among others. Such themes were embraced by the new minister of the interior, Count Nikolay Ignatev, who proposed a series of new restrictions on Jews that eventually became the May Laws which went into effect in May 1882. The May Laws further restricted Jews to living in the Pale of Settlement and prohibited Jews from living outside of larger cities and towns, owning or managing real estate, leasing land, and operating their businesses on Sundays or other Christian holidays. Further restrictions continued to be implemented under Alexander III's rule.

All of Alexander III's reforms aimed to reverse the liberalization that had occurred in his father's reign. The new Emperor believed that remaining true to Russian Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality (the ideology introduced by his grandfather, emperor Nicholas I) would save Russia from revolutionary agitation that was responsible for the assassination of his father. Alexander's political ideal was a nation composed of a single nationality, language, and religion, all under one form of administration.[30]

***

(1894–1917) In the Reign of Nicholas II

The reign of Nicholas II was a time of great ferment though it is difficult to know exactly how the events of the period affected those who lived in the small townlets of Mlynov and Mervits. We know that Russian Jewry in general reacted with growing alarm and pessimism to the pogroms of 1891–92 and the restrictive legislation that was implemented by Alexander III and continued by his son Nicholas II who became emperor in 1894, and who presided over multiple significant events in Russia and on the world stage. Nicholas II would be faced with the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, the first Russian revolution in 1905, to which he responded with its bloody repression, another series of pogroms between 1903–1906, the outbreak of WWI in 1914, and the end of the Tsar's reign in 1917. This is the period of massive migration to the United States, the birth of political Zionism, and the growing support among Jews for radical movements like socialism, among other changes. Jews of the period who were aware of these impulses were thus faced with a new set of choices and decisions.

After Russia was defeated in the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War, long simmering tensions broke forth in riots, strikes and unrest across the Russian empire in what is called the Russian Revolution of 1905. Nicholas responded with the violent repression called Bloody Sunday. The riots foreshadowed the later Revolution of 1917 that brought the Bolsheviks to power and gave birth to the Soviet Union. In the wake of the Revolution, there was some hope of change with constitutional reform (namely the "October Manifesto"), including the establishment of the State Duma, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906. Some Jews had some hope of liberalization in some of these changes which promised basic civil rights and an elected parliament called the Duma, without whose approval no laws were to be enacted in Russia in the future.

Nonetheless, this was the period in which, as a result of these events, Jews immigration to the United States grew rapidly, coupled with a growing pessimism about the earlier strategy of integration as a means to acceptance in Russian society.[31] In this period, we witness increased support for a political vision of a Jewish homeland, being named now for the first time as "Zionism," though some Russian forerunners, such as Leo Pinsker, had already given up on the strategy of integration in the wake of the 1881 pogroms. Pinkser, who was born in Poland but grew up and was schooled in Odessa, published his pamphet entitled, "Autoemancipation," in 1882, subtitled (Warning to His Fellow People, from a Russian Jew),and became a leader of the Russian movement for a homeland called Lovers of Zion (Hibbat Zion or "Chovevei Zion") which had its first ingernational conference in 1894. The organization had begun to set up agricultural settlements in Palestine even before political Zionism got its start in 1896 when journalist Theodore Herzl published Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews), and established the first Zionist Congress in 1897.

We don't know whether these new ideas and growing pessimism about integration reached the small communities of Mlynov or Mervits at the time. We have a number of photos of Zionist youth groups in the Mlynov Muravitz Memorial book, but most of which appear to be from the 1920s and 1930s. We do know that at least one Mlynov-born person, Solomon Mandelkern, was an early supporter of Lovers of Zion (Hibbat Zion) and Herzl's Zionism and attended the first Zionist Congress in Basle in 1897. Imagine that. Mandelkern had left Mlynov in 1860 at the age of 14 and by the 1890's was living in Odessa. If they knew what had happened to him, I imagine his relatives back in Mlynov debating with villagers about whether Solomon's embrace of Haskalah (enlightenment) and his participation in Herzl's first Zionist Congress.

Not all Jews were persuaded by the Zionist vision, to be sure. Many joined socialist efforts which held out a vision of a nation state in which ethnic and religious differences would no longer matter. The Bund or "General Jewish Labour Bund in Russia and Poland" was founded in this period in Vilnius on October 7, 1897. The Bund sought to unite all Jewish workers in the Russian Empire into a united socialist party, and also to ally itself with the wider Russian social democratic movement to achieve a democratic and socialist Russia.

Though the visions were incompatible, some Jews were chosing Zionism and Socialism for many of the same reasons; some had begun to doubt that the liberals goal of integration would be an effective strategy for achieving civil rights in the Russian State and perhaps in any state at all. This was thus a complex and creative period in the history of Russian Jewry, a formative time for debates among Jewish thinkers on the nature of nationalism, the causes of Judeophobia, the idea and need for a homeland where Jews could be normalized, and the best way to deal with the modernizing trends of the late 19th and early 20th century. It is easy to read history in hindsight, especially after the Holocaust, and think that those who chose Zionism or immigration to the US were prescient. But at the time, Jews were divided as a community about which path was best for achieving civil rights and equality with other peoples.

***

Mlynov and Mervits Life Under Nicholas II

It is an interesting imaginative exercise to try to imagine what the residents of the small townlets of Mlynov and Mervits were experiencing during these massive changes in Russia. Indeed, one of the challenges when trying to imagine and history of townlets such as these, off the beaten track, is that we have to extrapolate from the events going on to their impact on those who lived there.

Despite the widespread pogroms in 1891–92 and increasingly restrictive legislation under Alexander II, we know of only Getzel and Ida Fax who left Mlynov for the US around this time. It would appear that the other families from Mlynov and Mervits either were not yet sufficiently worried about their situation in Russia, or they did not yet have the wherewithall to leave. For example, David Rivitz, the brother of Ida Fax, was apparently traveling back and forth from Mlynov to Baltimore during the 1890s, but was not ready to make a permanent move there until 1901. It appears he was waiting for his sister and brother-in-law to achieve enough stability in Baltimore before making his own decision to settle there permanently himself and then to bring his family. By early 1901, David and another Demb husband, Samuel Roskes, joined Getzel and Ida Fax permanently in Baltimore. Migration from Mlynov to the US, and Baltimore in particular, would begin to increase between 1901 and 1910, though the second and largest wave of Mlynov migration to Baltimore would be come later between 1910 and 1914.

The apparent slow pace of migration in the 1890's is thus suggestive of what the families from these villages might have been experiencing at the time, since we have very few direct memories of this period in written or oral traditions. Clara Fram's memory of her father's travel back and forth between Mlynov and Baltimore in the 1890's seems to confirm that it was unusual enough at the time to deserve a nickname for her mother, who was called "Pesse the American," since her husband was always in America. Clara has idylic memories of her life in Mlynov at this time when she was a little girl. She writes:

We are traveling not by a car or train, but with a horse and wagon! Life in this townlet is very pleasant, since the inhabitants know each other well. Each housewife practically knows what the other is cooking. Life in this town is so intimate that nick-names describe some of the people, caricatures not by pen and ink on paper, but by word of mouth. For instance, there is “Chaim, the Long One,” a very tall fellow, skinny as well, and very lazy; he just doesn’t want to work. And then there is Moshe, the water-carrier, a man who is seen daily on the streets, two buckets of water suspended on a rod across his shoulders, with which he fills the water barrel each housewife has in her kitchen.

And, there is Reb Henoch, worthy Rabbi of the town, a scholar greatly respected; but he has evidently failed to note that life has been changing perhaps advancing. For there he is on his way to the synagogue, dressed like George Washington; George Washington with a beard, a long silken coat, short trousers, long white stockings and low shoes. Another well-known man in the town in Shimeon Melamed, the Hebrew teacher, whose assistant can be seen, most of the day, carrying on his shoulders, to the class, protesting pupils, some even crying, but each one equipped with a bagel for comfort.

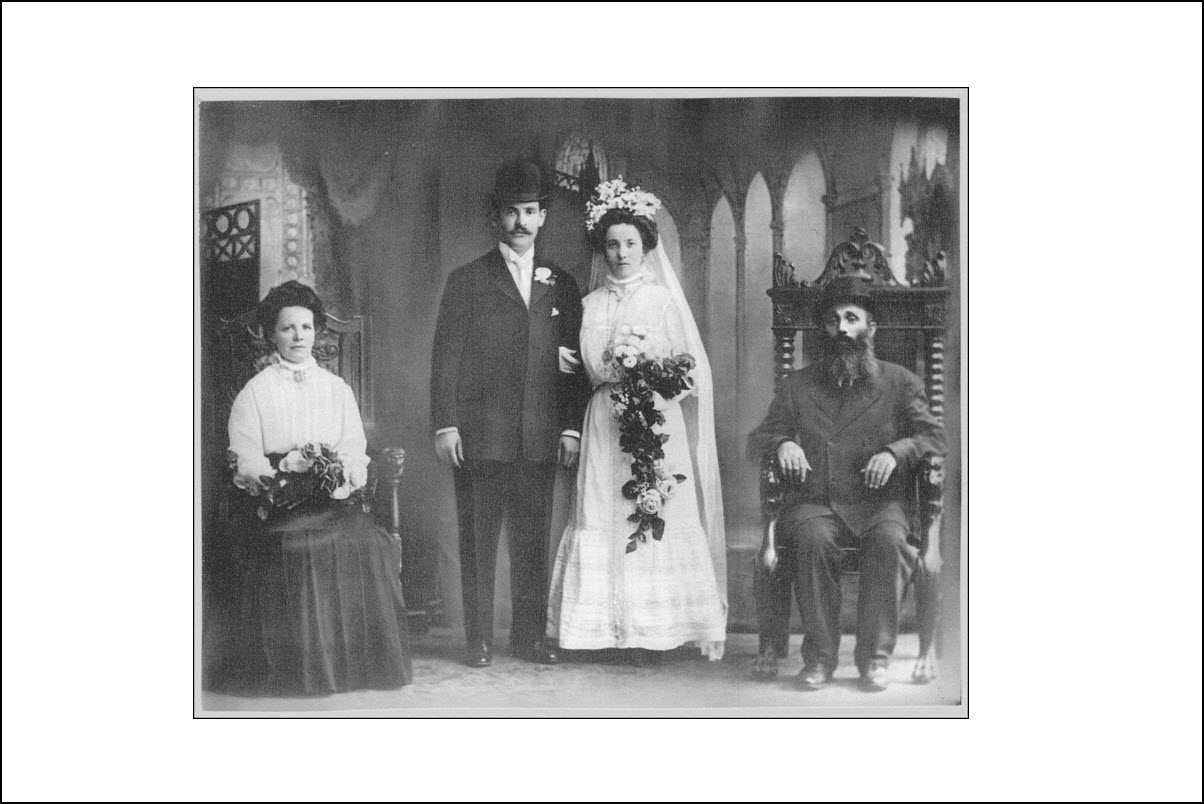

And, in the adjoining house lives Pesse the American, a name given to her because her husband keeps going to America and returning, because he doesn’t want to raise his children in the “traife” America. And, if you are a little girl in the house of Pesse, the American, you live in a wonderful spot; the Synagogue is across the way and today is an exciting day, for it is Friday. And while you are playing with mud pies that you place in an opening or aperture in the wall left by a loose brick, like your mother does in the house with the chollas for Shabbos, you watch and you listen, for you know soon they will come. And, suddenly there they come; singly, by twos and by threes, carrying clean underwear on their shoulders, the men, the Jewish men of the town. “They are going to the ‘Merchatz’ (ritual bath house)” your mother says. But you know! You also know that in the afternoon they will return; and truly, there they are, their dirty underwear on their shoulders, their faces shining, ready for the Sabbath! Clara's mother, Pesse (Demb) Hurwitz (left), was called "Pesse the American" when her husband David (right) was traveling back and forth from Mlynov to Baltimore in the 1890's. Here they are in Baltimore in 1910 at the arranged wedding of their daughter Minnie (center), who was married off to her uncle, Sam Fox, the brother of Getzel Fax. Courtesy of Carol Engelman

Clara's mother, Pesse (Demb) Hurwitz (left), was called "Pesse the American" when her husband David (right) was traveling back and forth from Mlynov to Baltimore in the 1890's. Here they are in Baltimore in 1910 at the arranged wedding of their daughter Minnie (center), who was married off to her uncle, Sam Fox, the brother of Getzel Fax. Courtesy of Carol EngelmanAnd tomorrow! It is the Sabbath. And, if you are that little girl in the household of Pesse, the American, today is the most exciting day. The Synagogue, as you know, is across the way. You watch the men entering via the main door to the left, while the women use the staircase on the right that leads to their balcony in the synagogue. And, during the service, when the men below are the Bible, call the “Teich Chumash”, reading the portion of the week. But there are many women who cannot read! Never mind. They go down the staircase into the street and across the way to the house of Pesse, the American, because they know that there sits a little girl of five on the floor, as there are not enough chairs, her mother’s teich-chumash on her lap, and she is reading the portion of the week in Yiddish for the women seated around her who cannot read themselves. That little girl was me!

A person from Mlynov drawing water from a well. Date unknown. Memorial Book, 94.

A person from Mlynov drawing water from a well. Date unknown. Memorial Book, 94. A character from Mlinov, Herschel Datino, carrying water in buckets 1938 next to Jacob Holtzeker's (Goldseker's) house in 1937/38. Memorial Book, 79.

A character from Mlinov, Herschel Datino, carrying water in buckets 1938 next to Jacob Holtzeker's (Goldseker's) house in 1937/38. Memorial Book, 79.It is hard to reconcile these and other idyllic memories of Clara's childhood with the reign of Nicholas II, which points to the difficulty of reconstrucing life in small townlets like Mlynov and Mervits without more first hand accounts. Of course, Clara's are childhood memories which one often tends to romanticize in later life. Just how much were the adults worried about their situation in the period after the pogroms is difficult to say. Clara was born in about 1902. It appears her father may have left permanently to live in Baltimore before she was actually born in 1901 or shortly thereafter. Clara's memories would thus be of a time in Mlynov between 1904–1908, before she immigrated to America with her mother, two sisters, and grandmother to Baltimore in late 1908.

***

Imagining Mlynov and Mervits Life from 1903-1914 under Nicholas II

We can only guess what the reactions of ancestors in Mlynov and Mervits were after the outbreak of violence against Jews in 1903. Likely they heard the news and were shocked. Likely it further spurred on thoughts about immigration to the US in the tiny communities. Maybe they were aware of the debate across the university students and intelligensia about whether America or Palestine should be the national home. If the families living there were aware of these trends, they would have stood in the market place and debated the merits of Herzl's proposal to consider Uganda or thought about joining Bilu or later the Bund or other socialists groups. Others might have defended the views of liberals, that with further integration into Russian schools and language, that Jews would cease to be the objects of hate for the peasants. Deeply traditional Jews were also finding new language to defend the commitment to traditional forms of life, beginning to develop a new "orthodox" language that could contest the views of liberals, Zonists and socialists. How much these broader debates penetrated the landscape of Mlynov and Mervits, we can only guess. But likely they would have been talking about what happened.

In April 1903, ten years after Alexander II had been assasinated and the pogroms of 1881-82 had subsided, amother brutal pogrom in Kishinev (now Chişinãu, Moldova) in the southern part of Russia rocked the Jewish community and came to the attention of the world. 49 Jews were killed, a number of Jewish women were raped and 1,500 homes were damaged. American Jews began large-scale organized financial help, and assisted in emigration. The incident focused worldwide attention on the persecution of Jews in Russia and Kishinev in some ways became a rallying cry and symbol for Jews who believed liberal policies of integration were doomed to failure.

Another pogrom followed in Gomel in September that same year. There was a second wave of pogroms in 1904 and they foreshawdowed the wave of riots and violence that was approaching at the end of the war with Japan and in the 1905 Revolution. About 3,100 Jews died in this wave of violence. The violence against Jews, besides being fed by antisemitic stereotypes from local papers, was entangled in the economic changes caused by policies handling the serfs' emancipation, the dislocation caused by industrialization, famine conditions created by poor harvests in 1902-1903.

Smack in the middle of this time period was the 1905 Russian Revolution, bringing to a head all the growing dissatisfaction and revolutionary impulses that had been simmering and exacerbated by the rule of Alexander III. Clara Fram in her memoire does not mention the widespread rioting, even though the iron foundry of her grandfather, Moshe Gruber, may actually have been the one that is mentioned in historical sources as falling at this time under influence of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Historical sources also report that in the summer of 1906 strikes and demonstrations in Mlyniv involved some 200 workers and caused local authorities to seek help from Dubno county authorities.[32]

It seems likely, perhaps even probable, that all of these events accelerated the migration from Mlynov to Baltimore, as did the early success of Getzel and Ida in Baltimore, which provided a foundation for those who followed. After David Hurwitz and Samuel Roskes arrived in 1910, at least 10 other Mlynov residents left for the United States, the marjority of them headed to Baltimore. They included two of the Schwartz brothers and one of their wives; most of David Hurwitz' family, Samuel Roskes' wife and son, Meier Fishman, and some unidentified Goldberg immigrants headed to New York. A second larger wave of Mlynov immigrants would make their way to Baltimore between 1910–1914.

The first wave of migration from Mlynov (1881–1910) in Reign of Alexander III and son Nicholas II

See an overview of the Mlynov migration between 1890-1910 .

NOTES

[1] I relied heavily for this history on "The Jews in the Tsarist Empire, 1772–1825," in Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. 1. Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2010: 322-439. Shorter summaries are available online including: "Volhynian Voivodeship" in Wikipedia, "Partitions of Poland" in Britannica, and "Second Partition of Poland" in Wikipedia. A short overview of the period is also found in "Russia" in Jewish Virtual Tour. ↩[2] Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 328. ↩[3] Polonsky, "On policies under Tsar Nicholas I, see Polonsky," Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 357–392. I also relied on Michael Stanislawski, Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews: The Tranformation of Jewish Society in Russia. 1825-1855. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1983. For a shorter summary, see "Nicholas" in the Jewish Virtual Library. ↩[4] On Alexander II, see Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. 1, 392–440. ↩[5] On Alexander III, see Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. II, 3–17. A helpful summary of cultural and early Zionist impulses in Russia at the time is found in Walter Laquer, A History of Zionism. New York: Schocken Books, 2003, particularly the chapters, "Out of the Ghetto," Kindle Loc 361-1050, and "The Forerunners," Kindle Loc 1051–1925. ↩[6] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 346. ↩[7] Laquer, A History of Zionism, "Out of the Ghetto," Kindle Loc 361–1050, and "The Forerunners," Kindle Loc 1051–1925.See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 346, 355, 362. ↩[8] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 346. ↩[9] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 355. ↩[10] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 358, and Stanislawski, Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews, 13–34. ↩[11] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 360–361 and Stanislawski, Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews, 13–34. ↩[12] Clara Fram, "This Is My Story: I Write And Speak Of Myself." (hereafter Fram, "My Story") 1982. Part of a Continuing Education Through Senior Seminars, Amalie Sharfman, Instructor. Quoted with permission of the Fram descendants.[13] See Fram, "My Story," p. 3; and Wikipedia on "Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)" and Crimean War "Crimean War" in Wikipedia. ↩[14] Mordechai Rivitz's children, David and Ida, were born in around 1867, based on documentation from their passage to America, which suggests that their father Modechai was born at least 15 years earlier probably around 1847–1851. If he was conscripted at the age of 7 (between 1854–1858) and he was released after 15 years (circa 1859–1873), it would have been before the Russo-Turkish war. Therefore, I suspect that Mordechai Rivitz was involved in the Crimean War from 1853-56 and was released after that. The immediate cause involved the rights of Christian minorities in the Holy Land, which was a part of the Ottoman Empire. The French promoted the rights of Roman Catholics, while Russia promoted those of the Eastern Orthodox Church. The longer-term causes involved the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the unwillingness of Britain and France to allow Russia to gain territory and power at Ottoman expense. ↩[15] See David Sokolsky, Monument: One Woman's Courageous Escape from the Holocaust, 17–18. David's step-grandmother, Liba Tesler, originally told him this story and indicated that Avrum's last name was Kotel. However, in the Memorial Book, p. 478, it has his last name, and that of his son, as Fritsis. I spoke with David about this and he thought that we should assume the Memorial Book was correct. ↩[16] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 392–395, and 401 on Russian political terminology used to describe Jewish assimilation. ↩[17] See Polonsky,Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I,(396–7). ↩[18] See "Russia" in Yivo Encylopedia ↩[19] Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 404, 431, and Yivo. ↩ ↩[20] Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 397, 399. ↩[21] Shmuel Feiner, Haskalah and History: The Emergence of a Modern Jewish Historical Consciousness. Oxford: Littman Libray of Jewish Civilization.2002, 159-161. ↩[22] Fram, "My Story", p. 5 "Kalman Schulman" in Yivo Encylopedia. ↩[23] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 393, "Russian Empire" in Yivo Encylopedia. ↩[24] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. I, 393, "Russian Empire" and Laquer, History of Zionism, Kindle Loc 1344. ↩[25] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. II, 3-17 and a short summary in "Russian Empire" in Wikipedia. ↩[26] Fram, "My Story", p. 3. ↩27] Clara gives the date of Getzel's immmigration to Baltimore as 1890, which is consistent with the 1900 US census, which indicates that Getzel had arrived in 1890 and Ida arrived in 1891. Sometimes, however, these dates are mistaken. A possible passenger manifest from Sept 1891, of one Georg Fox, could be the manifest of Getzel Fax, though this remains unprovable. However, it is clear that at times Getzel adopted the name of George Fox in subsequent records. I will discuss this in further detail when discussing the migration to Baltimore. Recently, scholars have cautioned about seeing the 1881-82 pogroms as the primary and exclusive cause of Jewish migration to the US and the key event shaping the development of Zionism. See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol II., p. 4 and in more detail, Benjamin Nathans, Beyond the Pale: The Jewish Encounter with Late Imperial Russia Berkeley: UC Press. 2002. For migration numbers and the Russian ambivalence on migration, see Polonsky, Vol II, 20-21. ↩[28] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. II, 3-17. See especially the detailed and thoughtful discussion in I. Michael Aronson, Troubled Waters: the Origins of the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1990. On the locatin of the pogroms in 1881 see 47–57. ↩[29] See Aronson, Troubled Waters. ↩[30] See "Alexander III of Russia" in Wikipedia. ↩ ↩[31] See Polonsky, Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol II, 19-21. ↩ ↩[32] Referenced in the Wikipedia article on "Mlyniv", citing Bukhalo, H., Vovk, A., "Mlyniv, Mlyniv Raion, Rivne Oblast" (in Ukrainian), an article in The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR , an Ukrainian encyclopedia that provides knowledge about the history of places in Ukraine. It was approved by the Communist Party of Ukraine in 1962 and published for the first time the very same year. The encyclopedia is described "here". ↩***

ADDITIONAL READING

I relied heavily on the very thorough, "The Jews in the Tsarist Empire, 1772-1825" in Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia. Vol. 1. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. Oxford, 2010, 322-439. Hereafter, Jews in Poland and Russia.

Forerunners of Zionism and the development of Zionism in Russia are discussed in Walter Laquer, A History of Zionism: From the French Revolution to the Establishment of the State of Israel. New York: Schocken, 2013, Kindle Loc. 1051-1920.

On the pogroms of 1881-1882, see especially the Michael Aronson, Troubled Waters: the Origins of the 1881 Anti-Jewish Pogroms in Russia . Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1990.

For useful high level discussions of the period, see:

"Volhynian Voivodeship" in Wikipedia ;

"Partitions of Poland" in Britannica ;

"Second Partition of Poland" in Wikipedia;

"Antisemitism in the Russian Empire" in Wikipedia;

"Russian Virtual Jewish History Tour" in Jewish Virtual Library;

"Russian Empire" in Yivo Encyclopedia.***

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz

Updated:Feb. 2025

Copyright © 2019 Howard I. Schwartz

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History