-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Famous Persons From Mlynov

***

There are a number of well-known persons born in Mlynov including: Aleph Katz, Solomon Mandelkern , and Yitzhak Lamdan. Much is written about these figures. Hopefully, taking account of their origin in Mlynov will help shed light on their later creative lives. It seems noteworthy that two of these individuals became known for their poetry and all three were writers: Yitzhak Lamdan, wrote a famous poem in Hebrew called "Masada" after his migration to Mandatory Palestine. Aleph Katz was respected as a Yiddish poet in America and became a Yiddish journalist. Mandelkern made important literary contributions to the Jewish Haskalah (Enlightenment).

Evident in the lives of these individuals are the cultural, political and religious faultlines which Russian Jewry confronted, including Hasidism, Haskalah (Enlightenment), Communism, Zionism, immigration to United States, to name only the most important. Even a small shtetl like Mlynov produced individuals who were caught up in these trends and some passed through more than one of these ideologies in the course of their lives.

***

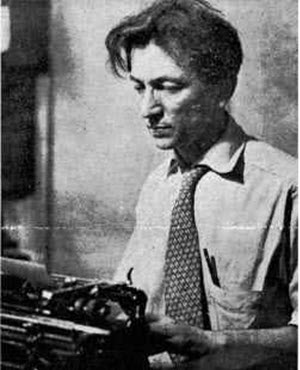

ALEPH KATZ (also Kats)

Aleph Katz, or just “Aleph” as he was often called later in life, was a well-respected Yiddish poet and journalist who wrote in the United States starting in the 1920s. He was born in Mlynov in 1898 as "Moshe Katz." His father and older sister left for New York in 1907 using his mother's surname of Hirsch. Moshe immigrated to the United States in 1913 at the age of 16 with his mother, Annie Katz (née Henya Hirsch), and two siblings, Hannah and Samuel.

Aleph's mother, Annie Katz, was one of the children of Aaron and Liebe Hirsch, a large respected family in Mlynov known as the "Ahrelas" family (children of Aaron). A number of Annie's siblings came to America. A photo of Annie (Henya Ahrelas) in New York appears in the Mlynov Memorial book, p. 500 (original volume).

Aleph’s father, Hyman Katz ("Chaim Yeruchem ben Reb Yacov Hakohen Katz") was ordained into the rabbinate, but became a follower of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment); Chaim Yeruchem was originally born in the town of Chelm and came to Mlynov and married Annie before 1893 when their eldest daughter Shifre was born. Chaim Yeruchim and daughter Shifre traveled to New York in 1907 under the surname "Girsh," a variation on Annie's surname of Hirsch. Apparently Chaim Yeruchim left behind a thousand-page Yiddish memoir about his youth and his first years in America, which is in Yivo collection.[1]

During his teenage years, Aleph worked in the Wet Wash family laundry of the Hirsch family in Jersey City. His first poems were in Hebrew, but in 1917 he published his first Yiddish poem in Der Groyser Kundes and published a stream of writing throughout his life. Most of the secondary literature about Katz appears to be in Yiddish and is not accessible without knowledge of Yiddish. A reviewer of his eighth book of Poetry in 1964, describes Katz’s work this way: "Aleph Katz' poetry is mystical yet vivid, tinted with rare imagery but in a mold and technique that rank him among the masters of the word."[2]

In addition to writing poetry, Katz served as a Yiddish editor of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency for more than forty years. The JTA was founded in 1917 and described itself and its initial mission then as follows: “The Jewish Daily Bulletin will be independent. It will not propagate any particular philosophy or theory or tendency. It will limit itself to the presentation of facts, leaving to its readers the forming of their opinion.”[3]

Read more about the Hirsch family from Mlynov or return to the top.

NOTES

[1] See the summary of the Aleph related collection in the Yivo Archives. ↩

[2] See Nathan Ziprin, "Off the Record." The Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, April 10, 1964, p. 6. ↩

[3] On the early mission, see JTA history. ↩

Additional Reading

Encylopedia.com overview of Aleph Katz

Overview of Katz and His Work by Yiddish Lexicon blogger Joshua Fogel.

An essay about Aleph Katz is also published in the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial Book.

Obituary of Aleph Katz from Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA).

Collection in the Yivo Archives.***

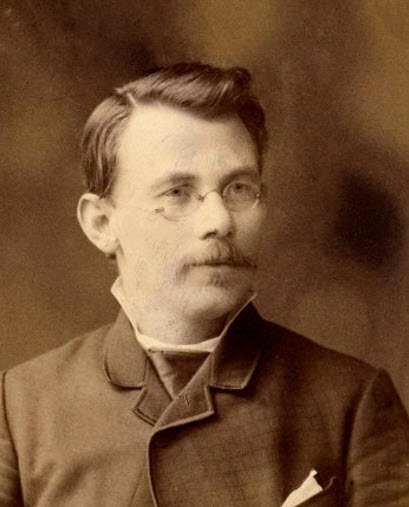

SOLOMON (“Simha”) B MANDELKERN (born in Mlynov 1846–1902)

Mandelkern was born in 1846 in Mlynov and died in Vienna March 24, 1902. He became a prolific writer in many languages. Mandelkern’s life reflects many of the themes and impulses of Russian Jewry during his lifetime, including a period of Hasidic influence, Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) and Zionism.

He was initially educated in a traditional way in Talmudic studies. After his father died unexpectantly in about 1860, he left Mlynov at the age of 14 and went to Dubno to continue his studies. He became associated with Hasidism there and went to the city of Kotzk and met the well known Hasidic Rabbi, Mendel of Kotzk, better known as the Kotzker Rebbe. There he studied Kabbalah (Jewish Mysticism) with the Rebbe's son, David, who later became the Kotzker Rebbe on his father's death.[4]

Mandelkern subsequently identified with the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment) movement, divorced his traditional wife, went to Vilna where he entered rabbinical school and graduated as a rabbi. In an article on Dubno, Mandelkern is listed as one of the well-known Haskalah writers that lived there in the 19th century.[5]

A bit of folklore recorded in the Mlynov Memorial book captures the enormity of his transformation. One day he was passing by his hometown Mlynov on the eve of the Sabbath. He stopped in his sister's store, but she did not recognize him without his beard, with his stiff mustache and and wearing a modern top hat.

Mandelkern also studied Oriental languages at St. Petersburg University where he won a gold metal for an essay on the parallel passages of the Bible, anticipating his subsequent drive to produce the concordance for the Hebrew Bible. In 1873, he became assistant rabbi in Odessa, where he was one of the first to deliver sermons in Russian and where he studied law. A degree of Ph.D. was conferred on him by the University of Jena. In about 1880, he settled in Leipsig. An early supporter of Hibbat Zion and Herzl's Zionism, he attended the first Zionist Congress in Basle in 1897. In 1900 he visited the United States and came to Baltimore where some of the early immigrants from Mlynov had already settled.

An essay written by Mandelkern’s great-great nephew, Colonel Bernard Feingold ( descendant of the Shargel family) summarized Mandelkern’s life this way:

As I grew older, I continued to be more and more intrigued by the accomplishments of Solomon Mandelkern. To this day I am in awe as to how a child (orphan) at that time in history, being of the Jewish faith in Tsarist Russia, could acheive so much in such a short time. From a small insignificant village, Solomon Mandelkern rose to scholastic achievements at the seminary and universities form which he graduated with the highest honors.

Mandelkern was a prolific writer in several languages, especially in Hebrew, in which he produced poetical works of considerable merit. His literary career began in 1886 with "Teru'at Melek Rab," an ode to Alexander II, followed by "Bat Sheba," an epic poem, "Ezra ha-Sofer," a novel (transl. from the German by L. Philippson), and a satirical work entitled "Hizzim Shenunim" (all published in Wilna).

The concordance to the Hebrew Bible was perhaps Mandelkern’s greatest and longest lasting contribution in his large corpus.For those who have never used a concordance, it is a powerful and critical tool for scholarly study. If you want to understand what a word in the Hebrew Bible means, you have to look at its meaning in all the other verses in which it appears. A concordance makes this possible. Mandelkern's impulse to produce the biblical concordance testifies to the mind of a thinker breaking free from traditional modes of Jewish learning and scholarship and exploring new modes of thinking.

When studying at the Jewish Theological Seminary in rabbinical school and later as a professor of Religious and Jewish Studies, I relied heavily on the concordance to the Hebrew Bible that Mandelkern compiled, never knowing then that its compiler, Solomon Mandelkern, came from the same small town as my paternal great-grandparents, who may have known him and his relatives. In rabbinical school, we referred to the concordance as “the Mandelkern” and we relied heavily on the two volume work for our research.[6]

An article in the Jewish Encylopedia lists the following among his works:

'Dibre Yeme Russiya,' a history of Russia (Warsaw, 1875; written for the Society for the Promotion of Culture Among Russian Jews; for this work he was presented by the czar with a ring set with brilliants [gems?]);

'Shire Sefat 'Eber,' Hebrew poems (2 vols., Leipsic, 1882 and 1889);

'Shire Yeshurun,' a translation of Byron's 'Hebrew Melodies' (ib. 1890). He published also: 'Bogdan Chmelnitzki,' in Russian,

a translation of Hanover's 'Yewen Mezulah' (St. Petersburg, 1878; Leipsic, 1883); a Russian edition of Lessing's fables (ib. 1885);

'Tamar,' a novel in German (ib. 1885; really a translation of Mapu's "Ahabat Ziyyon," without any mention of Mapu as the author).[7]

Return to the top.

NOTES

[4] Dates don't seem to align in the story. According to accounts, Solomon left Mlynov in 1860 and subsequently met Mendel of Kotzk. Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, who was called the Kotzker rebbe, died in 1859. See "Menachem Mendel of Kotzk." ↩

[5] See overview in Encylopedia Judaica. 2nd ed., Vol. 6, p. 33. "Dubno" ↩

[6] The photo of Solomon Mandelkern is in the public domain. ↩

[7] See Herman Rosenthal and Peter Wiernik, "Mandelkern, Solomon B. Simhah DOB." Jewish Encylopedia. 1906. Cited Oct. 24, 2019. ↩

ADDITIONAL READING

Herman Rosenthal and Peter Wiernik, "Mandelkern, Solomon B Simhah." Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906.

Wikipedia: "Salomon Mandelkern."

Jewish Virtual Library: " "Solomon Mandelkern."

Avner Holtzman, Trans. from Hebrew by Jeffrey Green, The Yivo Encylopedia of Jews in Europe: "Mandelkern, Shelomoh."

An essay on Solomon Mandelkern by his great nephew, Col. Bernard Feingold, "Solomon Mandelkern." In Generations. Jewish Historical Society of Maryland. Vol. II:2. 1981, 10-19.

A photo of and essay about Mandelkern in the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial Book.***

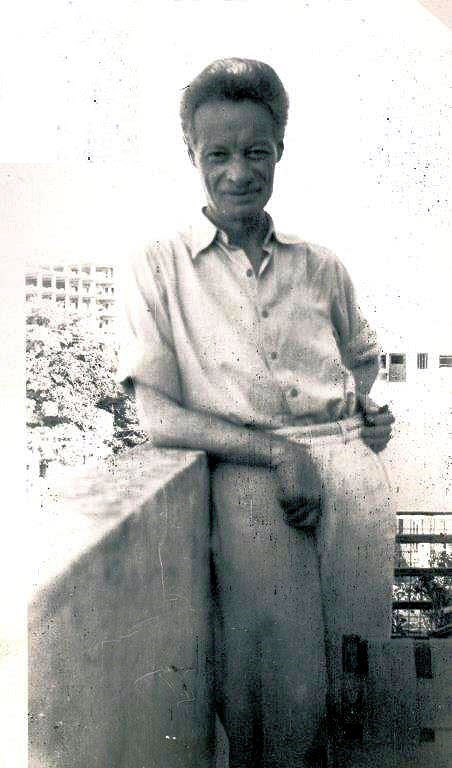

YITZHAK LAMDAN ("Itzik Yehuda Lubes") (born in Mlynov 1897–1954 Tel Aviv)

The poet, Yitzhak Lamdan, is probably the best known of the individuals born in Mlynov because of his important role in shaping Zionist ideology and Israeli national identity with his famous and influential poem, “Masada.”

Born in Mlynov in 1897[8] into an affluent family as “Itzik Yehuda Lubes” or Lobes (later Yitzhak Lamdan), Lamdan lived in Mlynov until the outbreak of WWI in 1914 and the civil wars that followed. During this period, he was uprooted and wandered through Southern Russia with his brother before joining the Red Army. Lamdan kept a Hebrew dairy during this period which includes his reactions to experiences in Mlynov, his longing to make aliyah, and his experiences at the beginning and during WWI. The diary which is published in Hebrew is being translated now into English on this web site. In 1920, after his parents’ home was destroyed and his brother was killed, Lamdan immigrated to Palestine as part of a socialist youth group in what has come to be known in Zionist history as the “Third Aliyah.” His poem “Masada” was written between 1923 and 1926 during his early years in Palestine while he was also involved in manual labor of various sorts.

During the early 1920s, we know that others from Mlynov were just beginning to make their way to Palestine as well, including the Fishman family who were among the early settlers of Balfouria, a new moshav whose name celebrated the Balfour Declaration, which advocated for a “national homeland.” (More on the Fishman migration.)

During this period in the early 1920s, some immigration to the US was still feasible as evidenced by several other Mlynov families who left for Baltimore between 1920–1924, though restrictions were beginning to tighten. Thus at this juncture Mlynov families were still making a choice whether to go to Palestine or the United States or stay in Russia. That choice was influenced by several factors including whether they already had relatives in the US, had financial help migrating, and their own ideology or personal commitments.

Moishe Fishman's eldest son, Benjamin Fishman, for example, flouted his parent’s choice of Palestine and left with other Mlynov families for Baltimore in 1920. The choice of America versus Palestine thus split the Fishman family. The US option would not remain open for long, as the US began imposing quotas, forcing those from Mlynov who wanted to join family there to try to get in via other routes such as Buenos Aires and Mexico. This is a useful background to understand Lamdan’s famous poem, which is in part biographical, reflecting on his own experiences exploring other options and becoming disenchanted with them.

The poem follows the life of a refugee who rejects the advice of those he meets on his journey as he makes his way to Masada, the mountain fortress to which Jewish “zealots” (or patriots depending on your perspective) had escaped as they resisted the Roman army encamped around them in 73 A.D.. The siege of Masada took place not long after the Romans had destroyed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem in 70 A.D and essentially ended the Jewish national entity until it’s refounding in the modern period. The story of Masada was originally told by the historian Josephus writing in the first century A.D and was purportedly based on the report of seven eye witnesses who escaped the mass suicide carried out by the other zealots in the fortress. Out of the ancient siege of Masada, Lamdan thus fashioned a symbol for the complicated and conflicted experience of the Jewish pioneers to Palestine and the Land of Israel. Like the zealots on top of Masada who felt beseiged on all sides by forces aligned against them, so in Lamdan’s poem were the Jews who lived outside the Land of Israel. Along the way to Masada, Lamdan’s protagonist rejects the advice of those who seek to deter him and offer him other options including: a believer who awaits divine retribution, a communist, and a person who is totally despondent. These are all options that Lamdan himself had explored and in the end rejected.

With help of Lamdan’s poem, Masada came to symbolize defiance against Jewish fate, and spoke to the hardship and difficult experiences and choices faced by the early pioneers. In this way, Lamdan helped forge Masada into a symbol of Zionist ideology itself, representing the Land of Israel as the last stronghold of the Jewish people, and the only remaining option. Not all of his friends and neighbors from Mlynov apparently would have agreed. In contrast to the first century version of the Masada story recounted by the historian Josephus, the Jews in Lamdan’s Masada do not commit suicide and thus do not ultimately give into despair. They are besieged but heroic in their response.

Lamdan’s Masada made a great impact on the Zionism of the interwar period up through the fifties. It became part of the school curriculum, both in the Land of Israel and in the Eastern and Central European diaspora (the Tarbut school network). Key lines were set to music and accompanied group dancing. "Masada" stood for the Zionist resolve to survive and ultimately to win, expressed above all in the powerful slogan "Masada shall not fall again".

Because of Masada’s important role in supporting if not shaping Zionist and Israeli identity, and in creating what is now called “the Masada myth,” a very rich and interesting literature has grown up interpreting the meaning of Lamdan’s Masada, and its role in myth making and national identity formation. These studies explore the source of Lamdan’s Masada, the original meaning of the poem in historical context and how and why it became a symbol Zionist ideology when it did. One important study places the poem into its contexts in the 1920s in Palestine and argues, quite convincingly, that it spoke to the conflicting experiences of the pioneers in that period. As the authors (Schwartz, Zurabavel and Barnett) put it:

The first manifestations of widespread Jewish interest in Masada coincided with the rise of Zionism during the early decades of the twentieth century. That the memory of Masada was “in the air” at this time is evidenced by the formation of a Masada Society in London and in Palestine by the translation of Josephus’s chronicle into modern Hebrew. However. the event that most effectively mobilized interest in Masada was the publication in Palestine of a poem by a Ukrainian immigrant. Yitzhak Lamdan. This poem titled “Masada.” enjoyed immense popularity when it first appeared in 1927. and its many reprintings were accompanied by great fascination with and pilgrimages to the fortress itself (Zerubavel, I980:27-35). Later, after spectacular archaeological excavations “confirmed” Josephus’s history (Yadin, 1966). Masada was transformed into a state-sponsored cult.[9]

In its setting in the 1920s when Lamdan wrote, the Masada of the poem may have had much more ambivalence about the settlers’ plight and situation than later Zionist ideology read into it. As Schwartz et. al. write, “Lamdan’s “Masada” revolves around two sentiments: defiant optimism, on the one hand, and an almost morbid pessirnisrn on the other. From this place, Lamdan offers the painfully real prospect that the centuries of wandering are not over, that fortress Masada provides no better protection for Jews in the twentieth century than it did in the first and that the fall of Masada will repeat itself "It is the last watch for the night of wanderings in the world. 'Soon the invisible scissor blades will yawn open and then close with a mocking creak on the chain of our dance..'"[10] The negative affect of the poem spoke to the settlers' experience in Palestine.

“Madada's" negative tone moved Lamdan's contemporaries because of its affinity with the conditions of Palestine during the 1920s. The reality of the historical Masada articulated (1) the settler's sense of being in a situation of "no choice": (2) their realization that the Zionist cause was a last stand against fate: (3) their sense of isolation from the main body of the Jewish people: (4) their despair and the essential ambivalence of their commitment to one another and to their new homeland; and (5) the very real prospect that the second Masada would fall in the same manner as did the first–by self destruction. Thus the effect of the poem was not only to make the situation in Palestine more hopeful or to bolster the collective ego–its effect was also to rnake that situation rneaningful.

Return to the top.

NOTES

[8] Lamdan's birthdate is the 5th of Kislevl 5676 / November 30, 1897 as evident in his diary which is now published in Hebrew. See "Introduction," p. 15, Yitzhak Lamdan's Diary. Annotated Critical Edition. Ed. Avidov Lipsker. Bar-Ilan University Press, Ramat Gan, 2015. The diaries are being translated into English. ↩

[9] Barry Schwartz, Yael Zerubavel, and Bernice M. Barnett, "The Recovery of Masada: A Study in Collective Memory," 146-164. The Sociological Quarterly 27:2, 1986, 14.↩

[10] Schwartz, "Recovery of Masada", 159.↩

ADDITIONAL READING

Wikipedia overview of "Yitzhak Lamdan."

A short discussion of "Yitzhak Lamdan’s poem Masada (1927)" in a blog on The Reception of Josephus in Jewish Culture .

A short discussion in Jerusalem Post (Jan 26, 2012) of "The Masada Complex."

A short overview in Encylopdia.com of "Lamdan, Yizhak."

Situating Lamdan in the "Third Aliyah", Howard Sachar, History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, p. 152.

An important academic account of the meaning of Lamdan's "Masada" in context, "The Recovery of Masada: A Study in Collective Memory," by Barry Schwartz, Yael Zerubavel, and Bernice M. Barnett, The Sociological Quarterly 27:2, 1986, 146-164.

A comprehensive discussion of the issues in the development of the Masada myth is Nachman Ben-Yehuda's The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel. Unversity of Wisconsin Press, 1995.

Steven Mock, Symbols of Defeat in the Construction of National Identity.

Return to the top.

***

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz Updated:May 2024

Copyright © 2019 Howard I. Schwartz

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History