-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Mlynov and Mervits in Interwar Poland (1918–1939)

***

Contents

The Return of Itzik Lerner | Optimism and Despair of Jews in Poland, Balanced Views of the Period | Trends Among Jews of Poland | Growth of Zionism and Zionist Youth Groups in Mlynov and Mervits | Mlynov/Mervits in the 1930s.

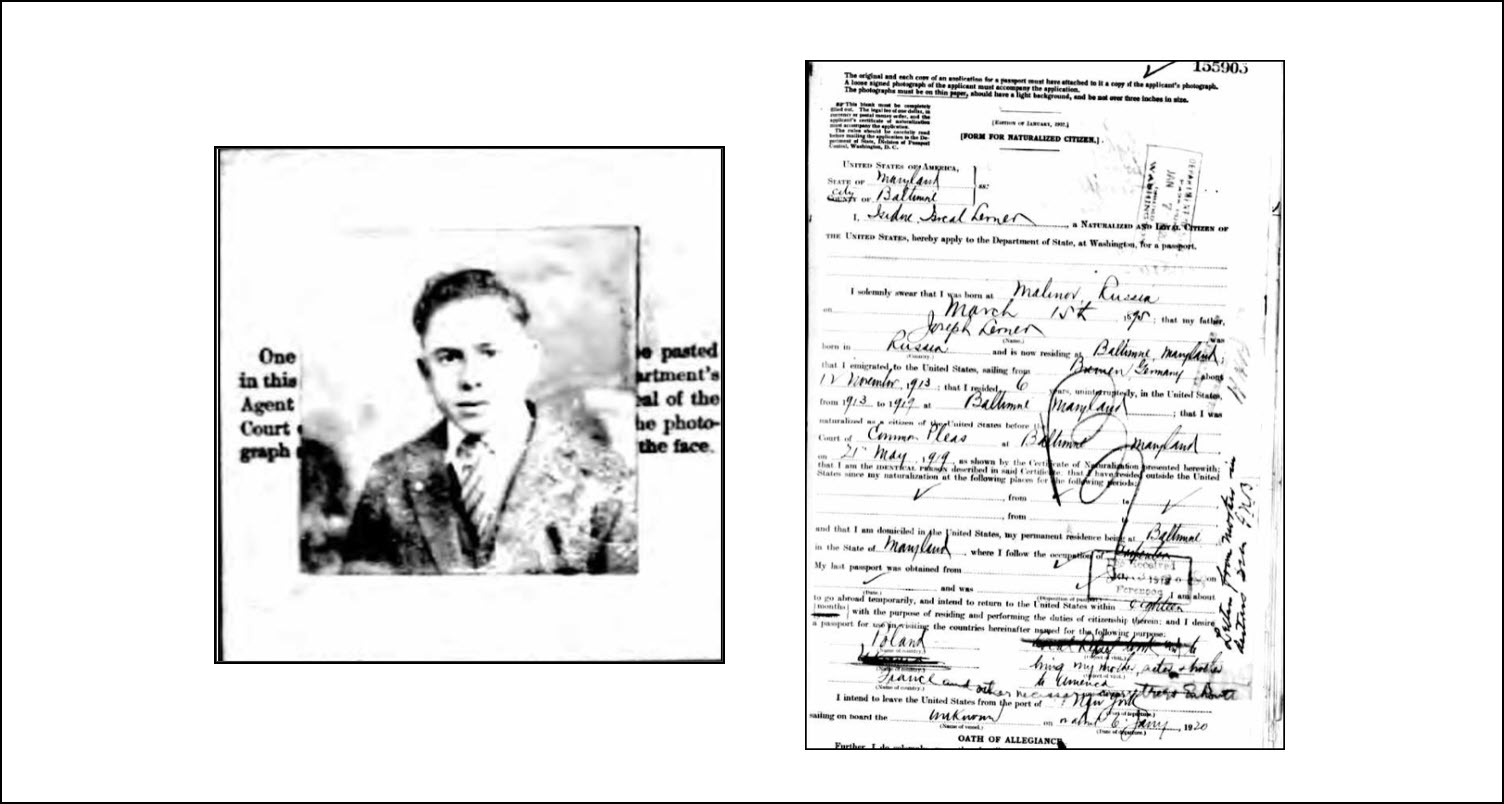

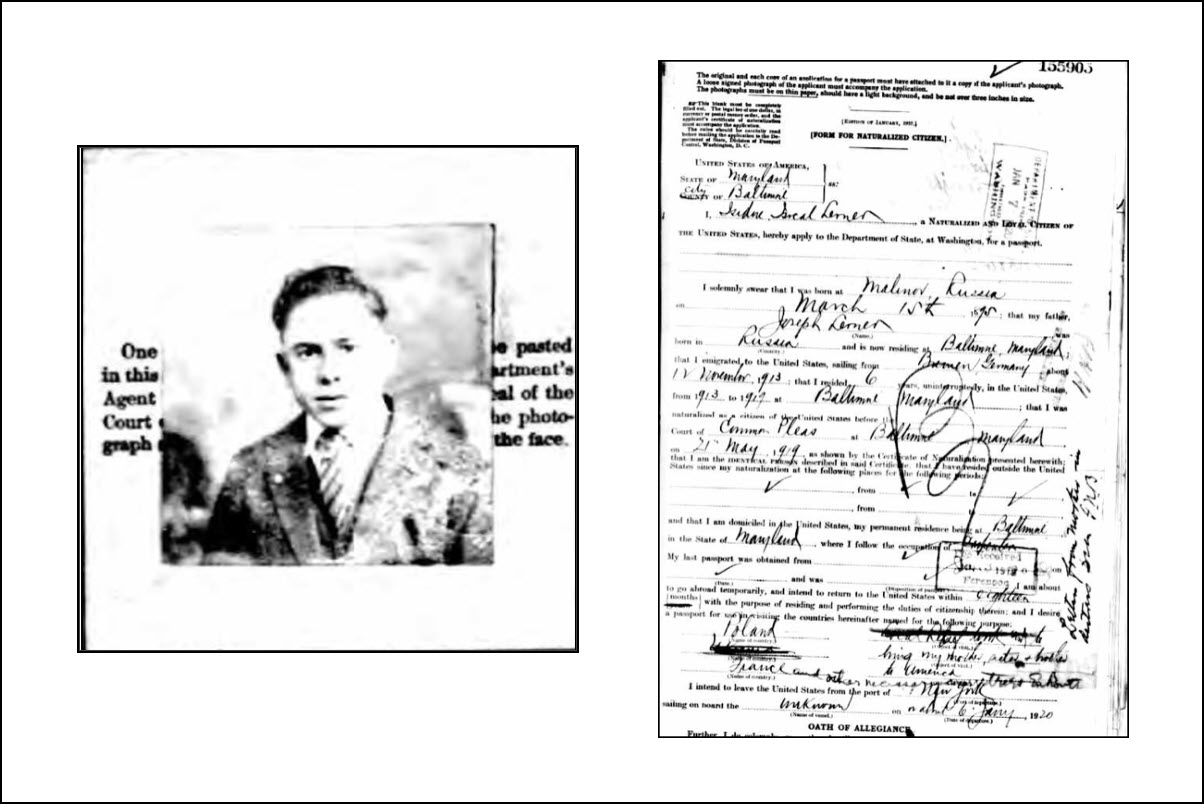

The Return of Itzik Lerner

In December 1919, just six months after the Treaty of Versailles formally concluded WWI, Itzik Lerner (now Isidore Lerner), the young Mlynov boy who had immigrated to Baltimore in 1913 to join his father Joseph, applied for a passport to return home to Mlynov. He wrote on his passport that his destination was to go back “to France and Poland and other countries” to assist his family. He scribbled on the side of his application that he had received “letters of distress from his mother because of the war.”

Itzik’s US passport application is among the first papers of any person from Mlynov or Mervits located that identifies “Poland” as the location where his or her family was living and thus marks a dramatic change in how residents from these towns would have to conceptualize themselves going forward.

They had always been from Mlynov and Mervits, but in the past they thought of themselves as born in Russia and as in some sense Jews of Russia, if not Russian Jews. But now they had to think of their towns as places in Poland and begin to think of their national identity as in some sense Polish. There would be new cultural pressures to learn Polish and to come to terms with a renewed Polish nationalism. This shift would take time to root itself in the consciousness of those from these small towns, and those born under Russia rule would need more time to adjust to their new identity, if they were to adjust at all.

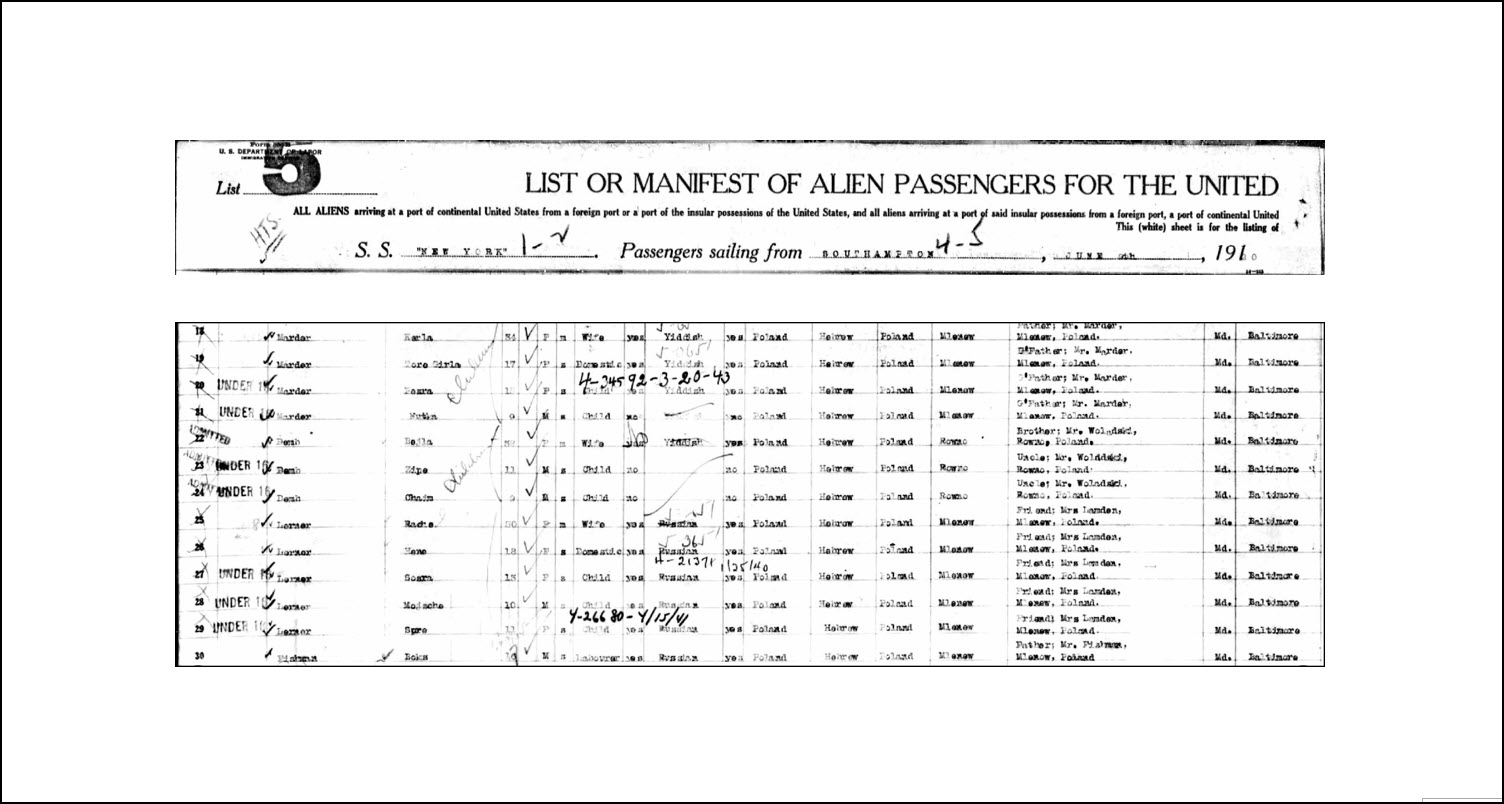

Itzhik’s passport application also marks the beginning of the third wave of Mlynov and Mervits migration to the US. As discussed earlier, between 1920–1925, quite a number of Mlynov and Mervits families and individuals made their way to the US and particularly Baltimore. During this period, Mlynov residents who had to fill out official paperwork had to identify themselves as of Polish nationality and get Polish passports to leave. We know from oral accounts and papers that some had to travel to Warsaw to get their passports. The passenger manifests of Mlynov and Mervits immigrants to the US in the 1920s all say that they were born in Poland, though in fact they had all been born in Russia. The few exceptions were Mlynov-born individuals, such as Simon Shulman, who was in further East in Berdichev when the Revolution started and never officially became Polish after the war. [1]

Mlynov, of course, was part of Poland before 1793 when Russia absorbed the area in the Second Partition of Poland. In that period, life under Polish-Lithuanian rule had been relatively good for Jews. By 1795, however, Poland ceased to exist as a nation, and now, one hundred and twenty-three years later, Poland reemerged once again as a national entity in November 1918.

As Mlynov-born Itzik Lerner planned his trip back to Mlynov in late 1919, it must have been a relief for Mlynov and Mervits families on both sides of the ocean that the World War had finally ceased. Still, a number of battles were taking place in the various civil wars that had not yet come to an end and which would ultimately determine the fate of Mlynov and Mervits as part of Poland.

***

Optimism and Despair of Jews in Poland

The individuals who were returning must have been wondering what now was on the horizon for themselves and their families? Would Poland be good for the Jews? What was life going to be like under this newly reconstituted nation? Would Poland again become a place where Jews could thrive, as it had been before the Russian Partition? It is easier to answer those questions in hindsight than it was at that point in time.

It is important to imagine what it felt like to live during this Interwar period, rather than to interpret the experiences of these small towns only in light of what happened later. The shadow of later events, of course, casts itself over this whole period and it has been hard for Jewish historians not to see this period as anything else but “On the Edge of Destruction,” to quote the title of one popular book on the period. [2] One must also be cautious not to see the lives lived during this period only through the later tragedy or through the eyes of Zionist influenced historians, whose national narratives condemned life in the weak shtetl and saw Israel as the only authentic response to Polish antisemitism.

***

Balanced Views of the Period

Recent scholarship on the period offsets this pessimistic narrative with a richer and more complex understanding of Jewish life in Interwar Poland.[3]

It is only natural that some of this same imbalance is apparent in what has been written about Mlynov and Mervits in the Memorial book that was produced in 1970. Many of the recollections of this Interwar period were from residents of these villages who had participated in Zionist youth groups, and eventually left Poland and made their way to Israel before WWII or as survivors who escaped the Nazis. It is only natural that their memories are refracted through their experiences, as they should be.

But to see life under Polish rule only in this way is to risk missing something important about the lives lived before their final moments and to pass over an opportunity to do justice to the full range of the experiences of those who once lived and thrived there. I believe we have both obligations. Thus, from the tidbits we do have about life during this period from the Memorial book, and from other contemporaneous sources and memories passed down in families, we have to imagine experiences and voices of those who did not survive including those who did not get to tell their stories. What would they have said about life in Poland had we interviewed them before 1939? What were their lives like from their perspectives before the final solution became apparent? Was antisemitism the dominant experience or was life also rich in other ways?

***

Trends in Jewish Poland

The rebirth of Poland likely generated some initial optimism among those returning to Mlynov and Mervits after the War and the hope that the new national home would provide more civil rights and freedoms than life under Tsars. In fact, the Treaty of Versailles which re-created Poland in 1919, included a “Minorities Treaty” that gave some initial hope to Jews, promising civil and religious rights to minorities that made up one-third of the new Poland’s population and calling out specific protections for Jews who constituted the second largest minority after the Ukrainians. Those civil rights were codified in the Polish Constitution of 1921. Capitalizing on these early protections, Jews participated actively in 1922 in the success of the Minorities bloc in the Polish elections, which achieved seats in the Polish assembly (the sejm).

Many Jews also had some hope that the subsequent coup d’état by Jozef Pilsudski in 1926 would be good for the Jews. Pilsudski, a legendary military leader from WWI, envisioned a multi-ethnic state that would grant civil rights to minorities and in this he clashed with his arch rival, Roman Dmowski, the leader of right wing Endek party, which grew in power over the decade and increasingly shaped politics in Poland upon Piludski’s death in 1935. Under Interwar Poland, there were swings of optimism and despair within all aspects of Polish Jewish life, including Zionism and the socialist Bund, as events gave hope of success and then later dashed those hopes. This swinging between poles (no pun intended) was due to “the experience of the Jewish community as a relatively powerless minority whose political fortunes were inextricably tied to outside forces over which they had little control.” In some ways, then, the period can be summarized by “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”[4]

The reborn Poland had the largest Jewish population in the world after the United States and thus its fate “was seen as a touchstone for how the Jews would fare in the independent states of east-central Europe.” Poland was a laboratory in which the various Jewish Ideologies-Zionism, Bundism, Folkism-could each be tested. The Polish Jewish population was in fact very diverse and politicized, as various competing political-religious visions and movements captured adherents in the Polish Jewish communities. More than one version of Zionism marked the landscape, and clashed with socialist, Enlightenment (Haskalah) and Agudas traditional ideologies which also claimed authenticity in Interwar Poland. In many ways, the diversity of the Polish Jews at the time is reminiscent of the diversity of Jewish life in the United States and Israel in the 20th century, with no single hegemonic view of Jews and Judaism. That diversity has to be born in mind as we approach the shtetl life of Mlynov and Mervits.[5]

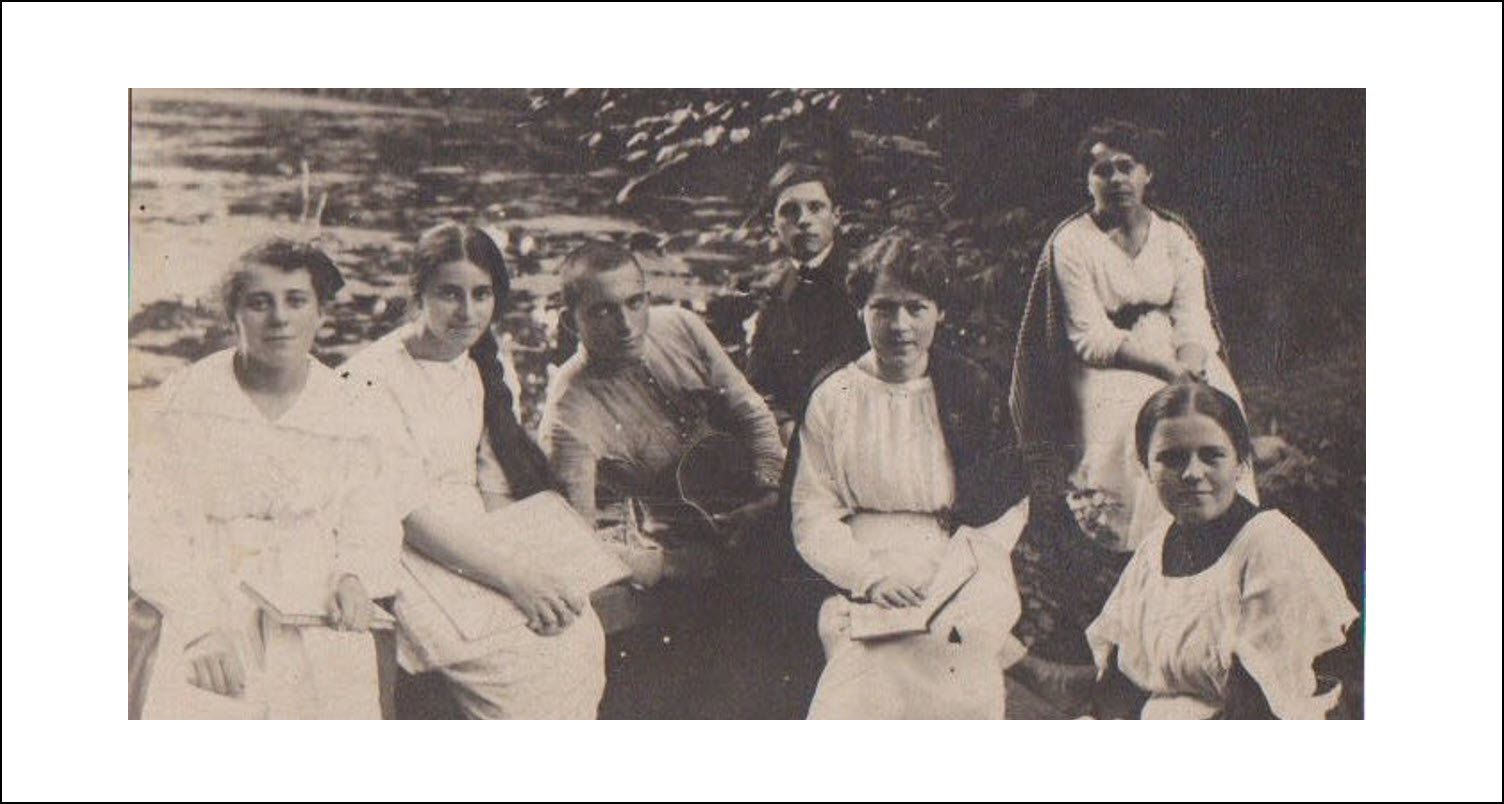

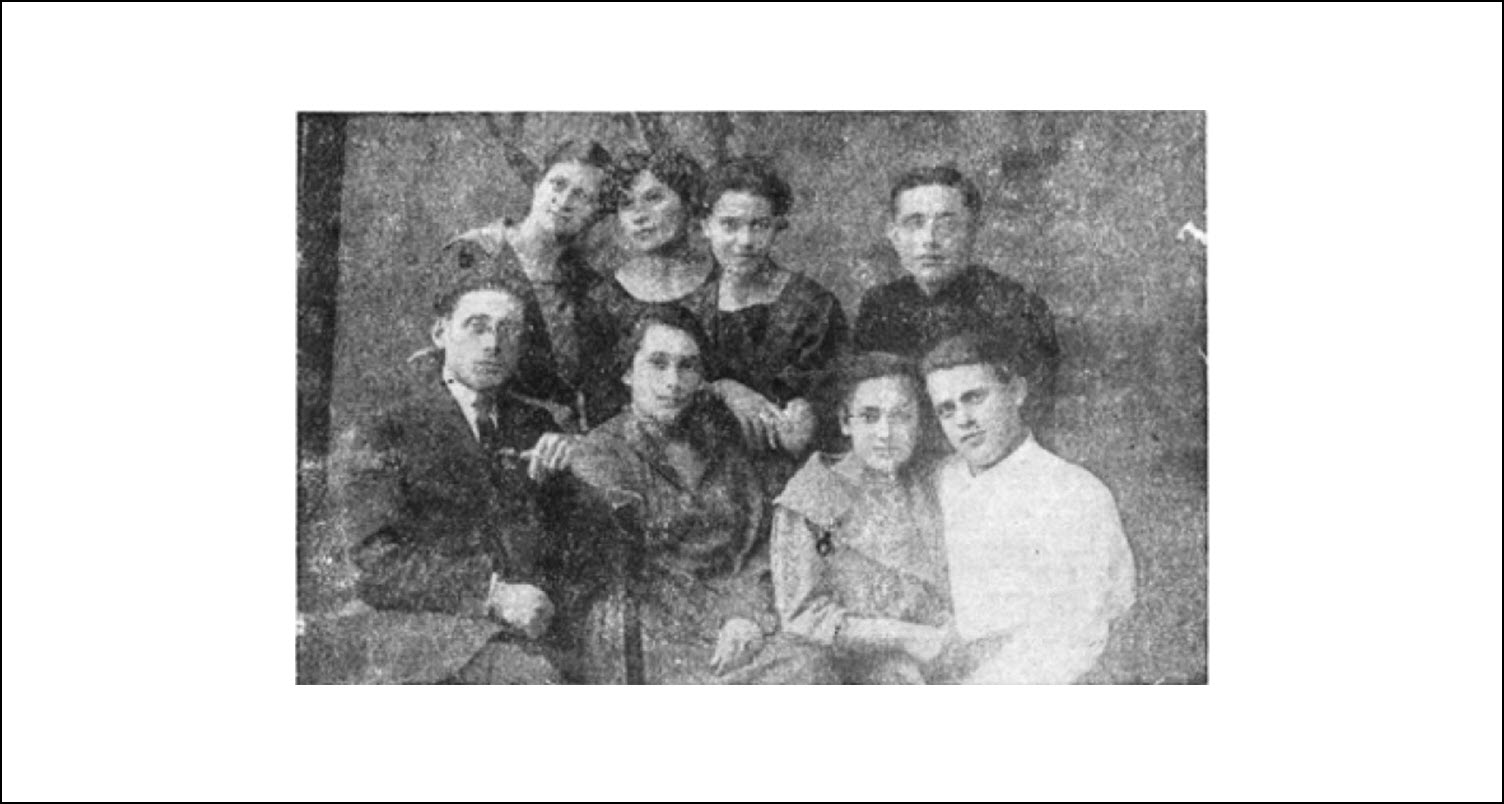

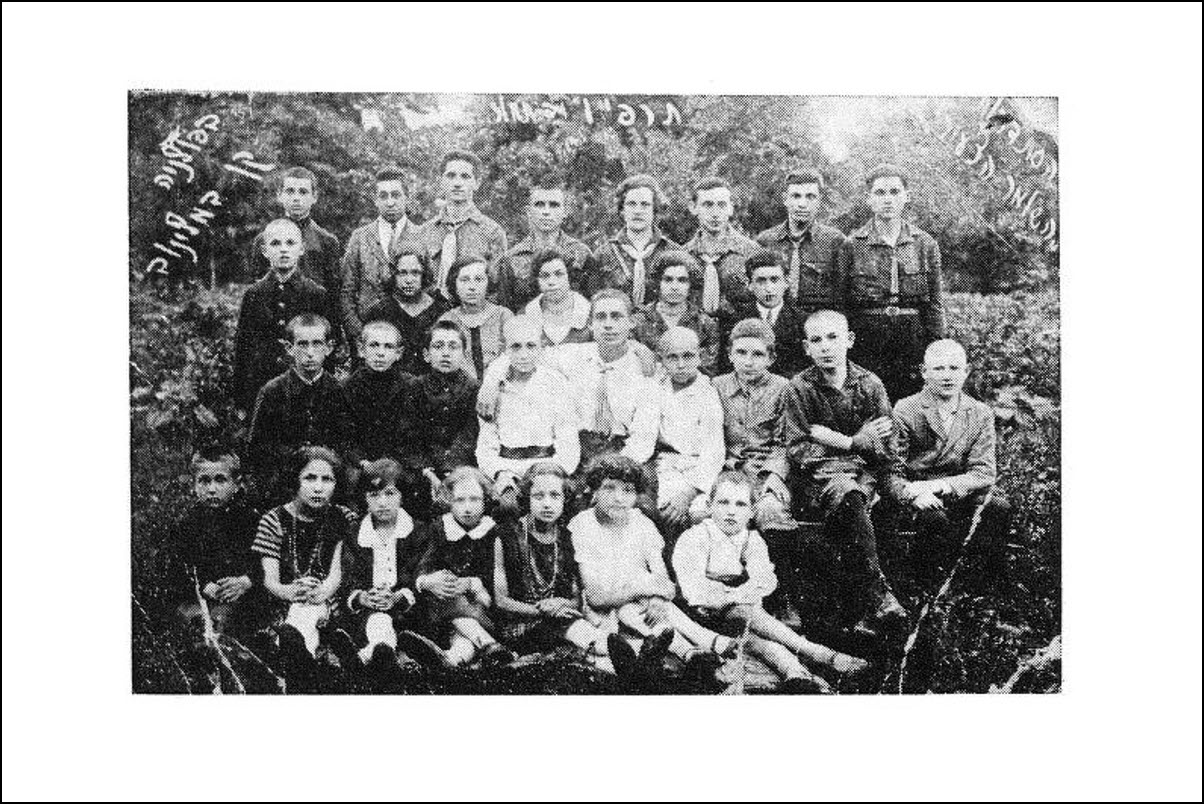

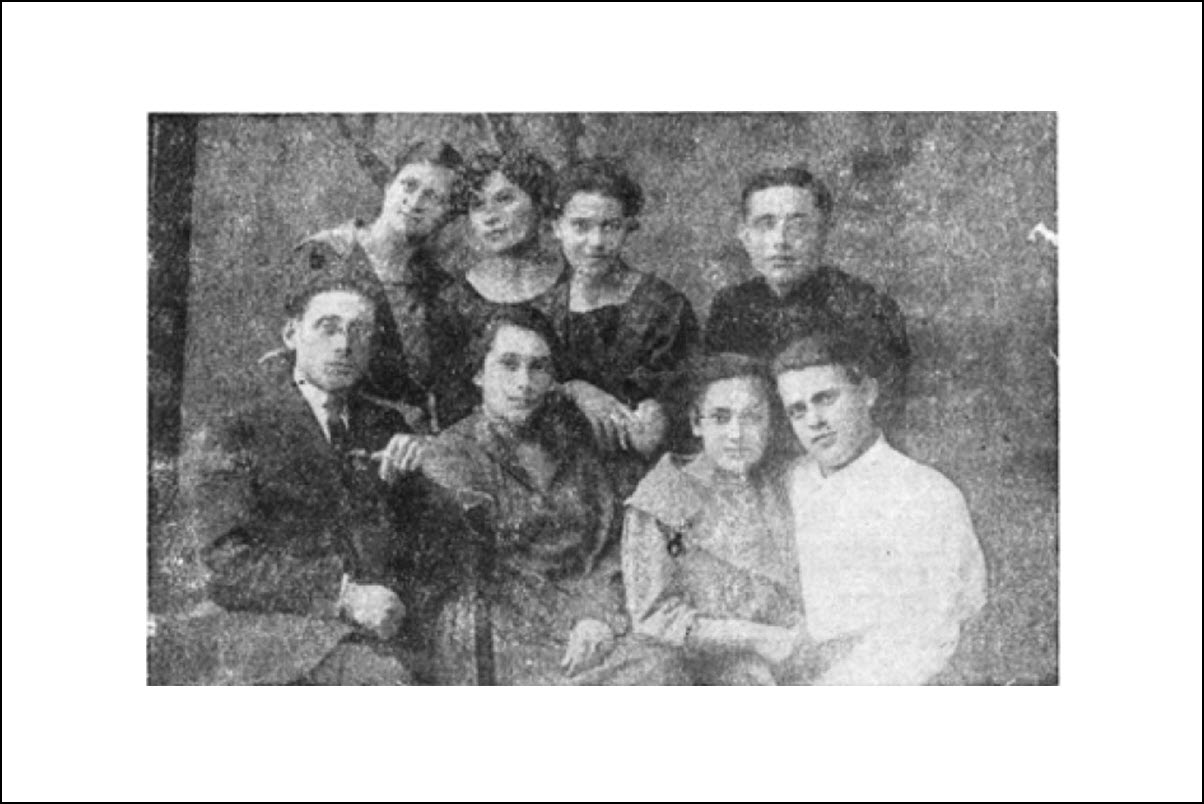

A photo of young intellectuals ("maskilim") teachers and cultural activitists ("Tarbut") (back row, right to left): The teacher Rachman, Miriam Mazlish, Malcah Lamdan, Devorah Berger, (front row, right to left): Schachat and his wife, Klara, the dentist, Shmuel Mendelkern. Mlynov Memorial Book, p. 61 [original p. 66].

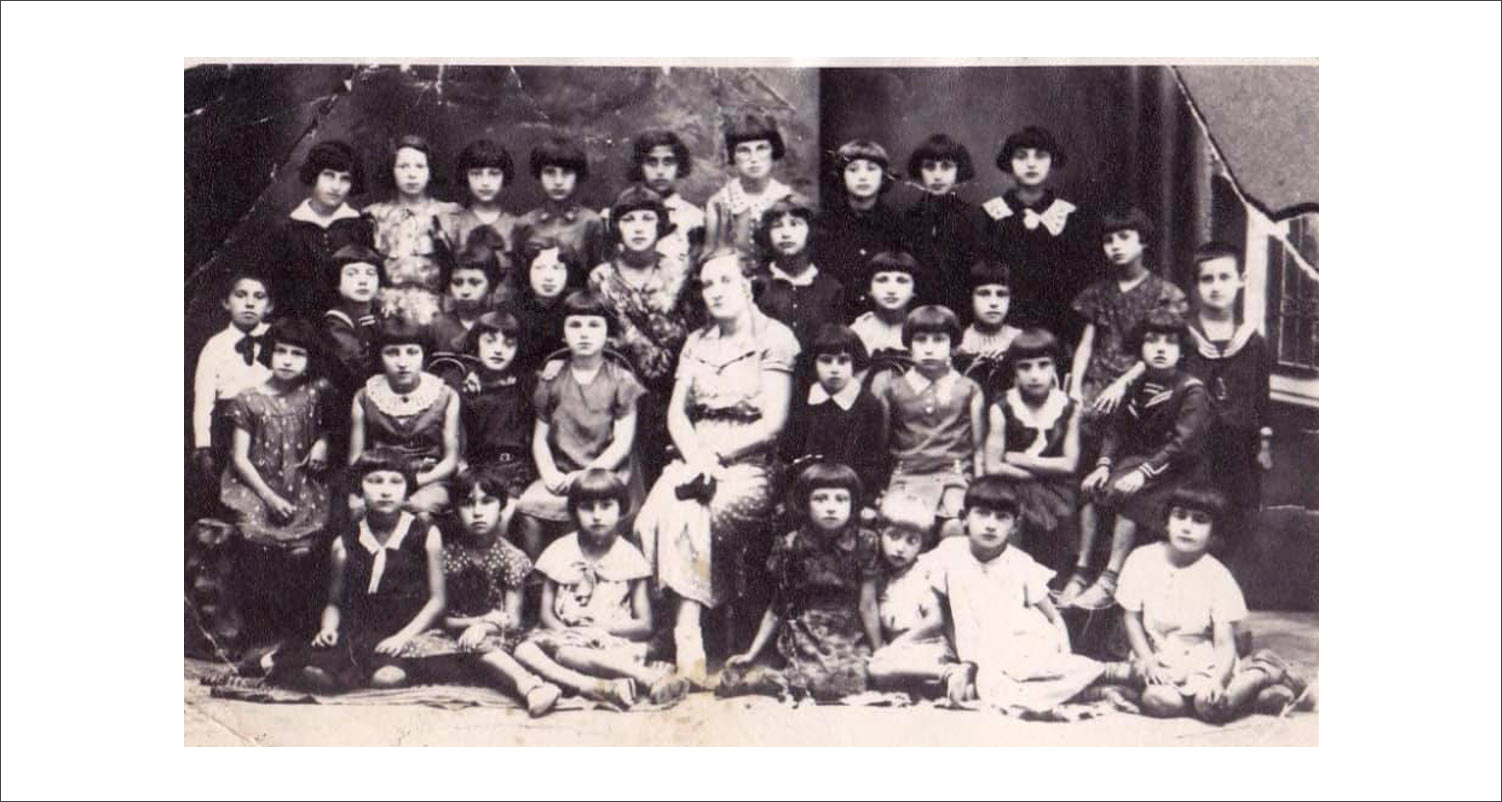

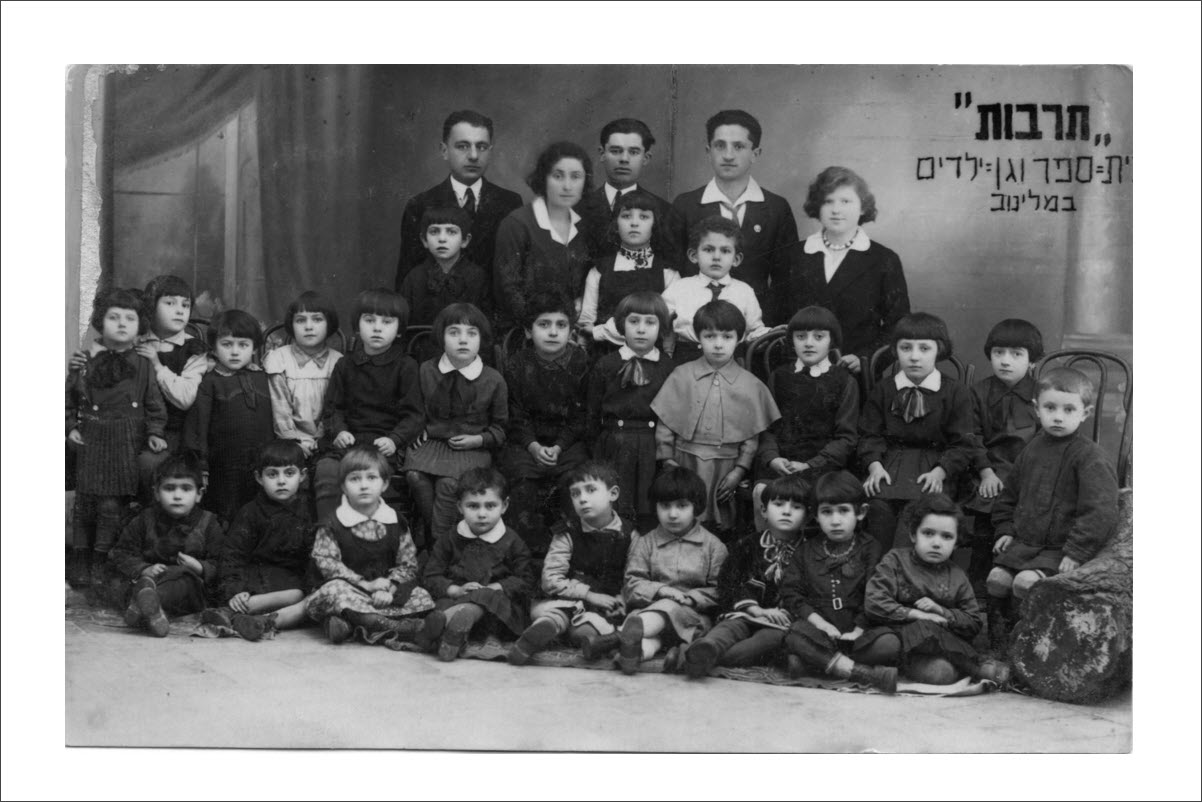

A photo of young intellectuals ("maskilim") teachers and cultural activitists ("Tarbut") (back row, right to left): The teacher Rachman, Miriam Mazlish, Malcah Lamdan, Devorah Berger, (front row, right to left): Schachat and his wife, Klara, the dentist, Shmuel Mendelkern. Mlynov Memorial Book, p. 61 [original p. 66]. Tarbut classes in Hebrew for youngsters became available in Mlynov during the Interwar period at the instigation of Shmuel Mandelkern. Mlynov Memorial Book, p. 51. Original photo courtesy of Zeev Harari. Individuals identified in photo listed below.[**]

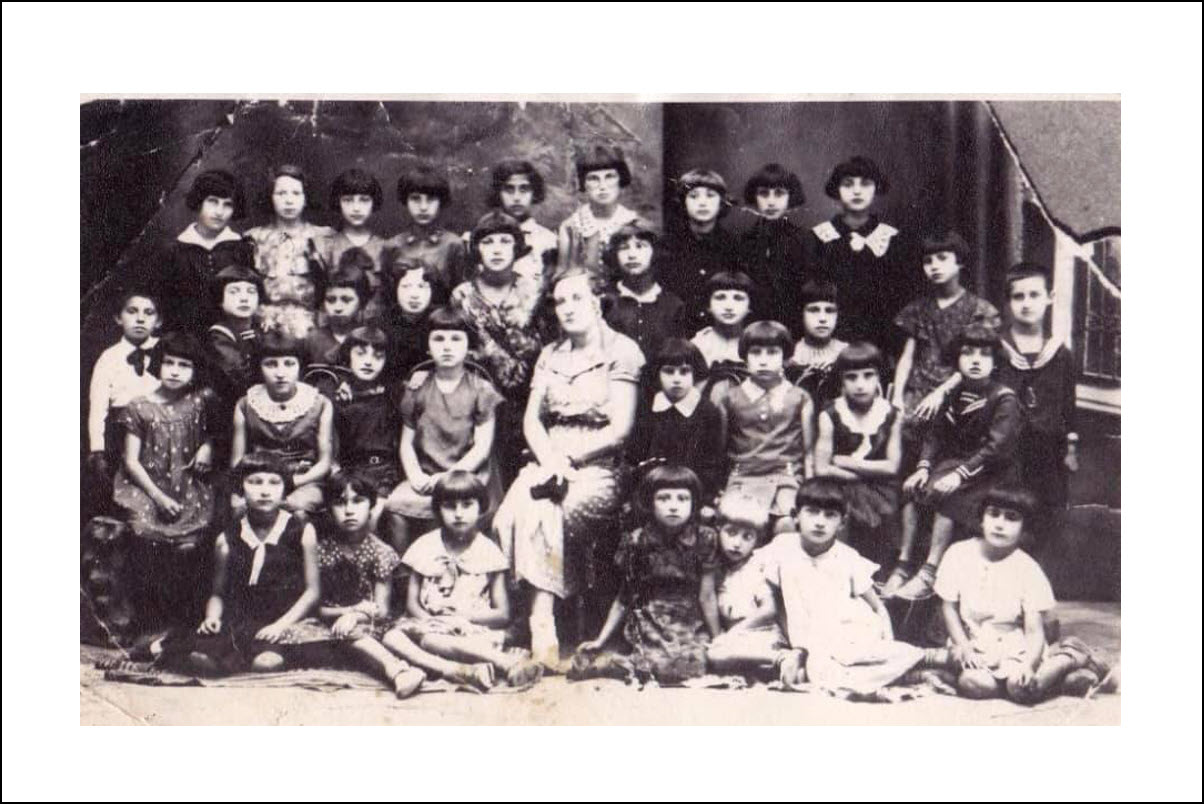

Tarbut classes in Hebrew for youngsters became available in Mlynov during the Interwar period at the instigation of Shmuel Mandelkern. Mlynov Memorial Book, p. 51. Original photo courtesy of Zeev Harari. Individuals identified in photo listed below.[**]Just how much the residents of the small towns of Mlynov and Mervits were pulled between these competing movements and trends is difficult to say, though fragments of stories and photos provide some clues that they did experience these competing pulls, as we shall now see. In reading the reminiscenses in the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial book and learning the oral stories of descendants, a number of themes recur that dovetail with and are illuminated by the larger trends in Jewish life of the period. Broadly speaking, they fall into the following categories: reflections on the growing importance of Zionist youth groups, poverty and economic hardship and relationships with non Jews, the all present but changing nature of religious life, nostalgia for daily life, and politicization.

Read more about the Zionist Youth Groups in Mlynov and Mervits.

***

[**] Aaron Harari-(back row, second from right). Genya Kozak: (aka Jean Litz in the US) front row, second from right. Chana Klepatch: second row from bottom, fourth from right).NOTES

[1] Although Simon Shulman was born in Mlynov, as were his siblings, his passenger manifest from 1922 says he was born in Stary Bykhov, Russia (now Belarus), which is where his father's family was born. Why so? While it is possible the Shulman family was there when he was born, I suspect that Simon was fudging his national identity after the War. But when the Revolution started, he was studying to be a pharmacist in Berdichiv. There he met and married his wife Edith Fixman. In her memoire, Edith recounts the chaos in Berdichiv when the Revolution started and that they eventually managed to make their way back to Mlynov and were surprised to learn that Simon's parents and the bulk of his family had left for Baltimore in 1921, before they returned. Simon and Edith managed to leave in 1922. I suspect that Simon and Edith were fudging this national identity in order to get their papers and used the birth location of Simon's father in place of their own.[2] See, for example, Celia S. Heller, On the Edge of Destruction: Jews of Poland between the Two World Wars. Wayne State University, 1994. Polonsky, for example, cites this book as an example of scholarship that sees the Polish Jewish experience primarily as a run up to later events. See Polansky, "Introduction," xvi, in Jews in Independent Poland 1918–1939. Ed. Antony Polonsky, Ezra Mendelsohn, and Jerzy Tomaszewski. Studies in Polish Jewish Polin. London: Litman Library of Jewish Civilization. Vol. 8, xv–xxi.[3] See Polonsky,"Introduction," xvi, and Ezra Mendelsohn, "Jewish Historiography on Polish Jewry," 3–13 in Polonsky,Jews in Independent Poland.[4] See Ezra Mendelsohn, p. 16, and his helpful account of Jews in Poland in this period in The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1983, 11-84). (see Mendelsohn "Jewish Historiagrphy in Polansky).[5] Polonsky, "Introduction," p. xvii, Mendelsohn, Jews of Central Europe, and the following essays from The Jews of Poland between the Two World Wars, ed. by Yisrael Gutman, Ezra Mendelsohn, et. al. University of New England, 1989: Mendelsohn, "Jewish Politics in Interwar Poland: An Overview" 20–35; on the Bund, see Brumberg," The Bund and the Polish Socialist Party in the late 1930s," 75–97, and Gershon Bacon on "Adudah Israel," 56-74.***

ADDITIONAL READING

Gutman, Yisrael and Ezra Mendelsohn et. al, The Jews of Poland between the Two World Wars. University of New England, 1989. See especially Ezra Mendelsohn, "Introduction: The Jews of Poland Between Two World Wars–Myth and Reality." 1–6, and Mendelsohn, "Jewish Politics in Interwar Poland: An Overview." 9–19. There are also very helpful essays on Polish Antisemitism by Gutman, The Bund and the Polish Socialist Party and Polish Commerce among other helpful essays.

Mendelsohn, Ezra. The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Bloomington: Indiana University. 1983. The chapter on "Poland," 10-83, is an excellent and nuanced summary of the trends, politics and impulses of the period for Jews.

Polonsky, Antony, Ezra Mendelsohn, and Jerzy Tomaszewski, eds., Jews in Independent Poland 1918–1939. Part of the Series: Studies in Polish Jewish Polin . London: Litman Library of Jewish Civilization. Vol. 8. There are a number of thoughtful and interesting essays in this volumen. See especially "Introduction" by Polonsky; Mendelsohn, "Jewish Historiography on Polish Jewry in the Interwar Period," 3-13, among others.

***

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz

Updated:August 2024

Copyright © 2019 Howard I. Schwartz

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History