-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Memories of Mlynov and Mervits

Contents

Memories of Place | Memories of Mlynov 1904-1907: Clara Fram | Memories of David "Sonny" Goldseker |

***

Memories of Place

The firsthand memories of Mlynov and Mervits, the places, come from persons who lived there at different moments of time and who recalled the places at later periods and from different vantage points in their own lives. Depending on circumstances, and what happened to them and their families, nostalgia and/or grief naturally shaped those memories of this tiny place, off the beaten tracks of Western Russia.

As small townlets, Mlynov and Mervits were insigificant to the Russian empire and, for the most part, the broader transformation of Jews that occurred under Russian rule. Even so, these broader trends touched down in these places as we can see from hints and memories left behind and the lives of a few of these villages offspring who went on to shape events beyond the confines of these villages.

It is perhaps inevitable for Americans to refract their memories of Mlynov and Mervits through the later images of Anatefka, the paradigmatic image of the shetl portrayed in the popular musical Fiddler on the Roof. And yet still, it is moving to read or hear accounts from people who lived there once, and recalled it, from a later time and place. For Mlynov and Mervits, and not the imaginary Anatefka, are the villages our ancestors came from. These are the places our grandparents and great grandparents courted, married, and had children. In the market days there, they purchased and sold goods and shared gossip. These are the streets where they left a piece of themselves behind. To imagine their village is to imagine something of their lives and to understand something about where we came from too.

It is not possible to think about those who lived in these places, without thinking also about the trauma suffered by those stayed behind and did not leave. The First World War was itself traumatic as the Eastern front moved back and forth near Mlynov and Mervits and required the population's evacuation. Some of the residents like Yitzhak Lamdin, lost their homes and family then, and left for Palestine shortly after in the Third Aliyah. Others left for America before and after WWI, joining the swelling ranks of those who sought hope there. For everyone who left and migrated, there were relatives still living in Mlynov and Mervits when the Russians and then Nazis invaded during WWII. For those families that had come back to Mlynov after WWI, only a few would survive. For good reasons, nostalgia and trauma are the twin poles of memories that have been left behind.

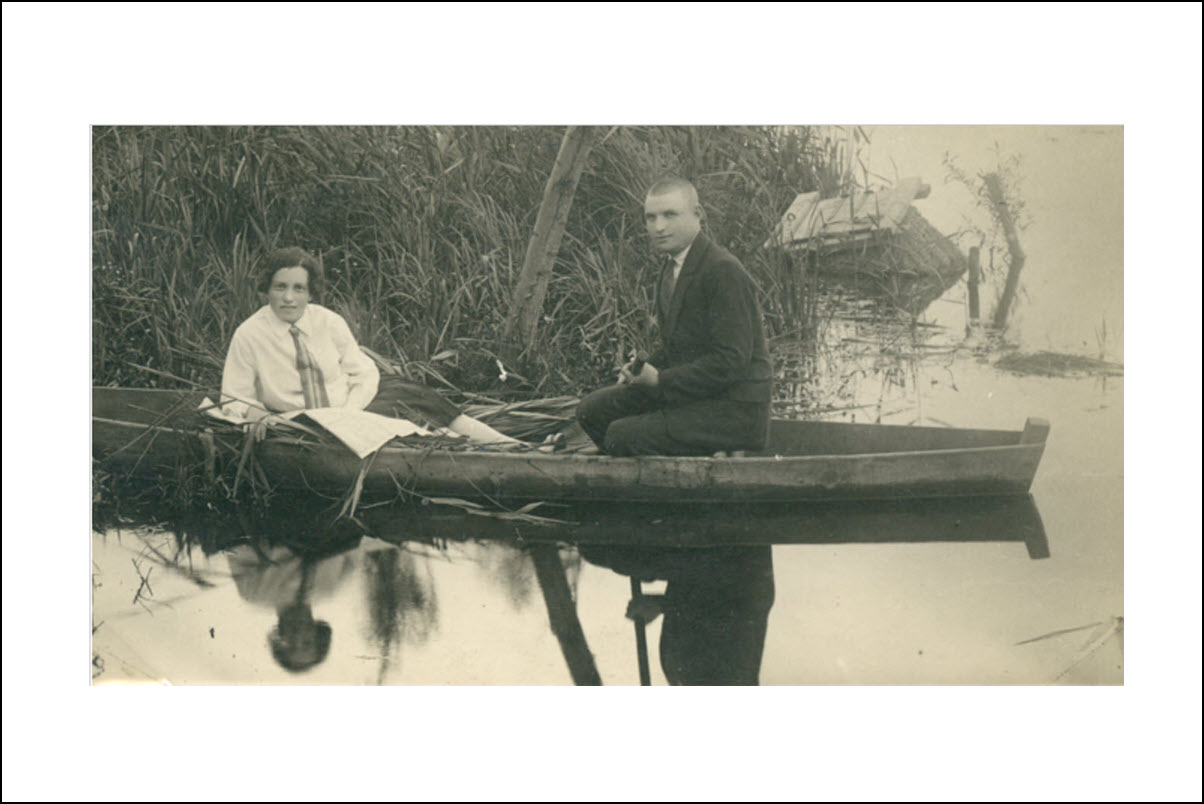

The memories Mlynov and Mervits tend to vacillate, between an idyllic townlet on the banks of the Ikva river, where young people boated and gathered, to an overly intimate place where everyone knew everyone else's business and where everyone was cousins to everyone else. What emerges is the image of a village which was, for all intents and purposes, an extended family, with all the rich and complex implications of that image. Not only do we find criss-crossing marriages among families, but DNA testing has started to validate shared lineages among descendants that go back beyond memory.

There are common themes as well that emerge from the memories of this place, even across time periods. Oral traditions recall the hovering presence of the local "Count" or "Graf" who owned the village land and set policy and laws that shaped the economic lives of the villagers who lived there. Several families recall their ancestors working for "the Count" and being dependent upon him for their economic well being. There are some memories too of interactions with non-Jews, though these are more sporadic.

Some memories and photos suggest that the population of Mlynov was traditionally minded religiously speaking and that village life revolved around the Sabbath and the three synagogues that were eventually there. But there are hints too that other impulses in the air had arrived in Mlynov. In the photos left behind, the oldest generation of women all wore the traditional headscarf ("tichel") which was associated with modesty. The next generation of women are not wearing the head coverings, suggesting that some impulses of modernism and enlightenment had already reached these villages and begun to liberalize religious practice and thinking.

A fully annotated translation of the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial volume is available and offers the richest source of memories of Mlynov and Mervits. The volume includes essays by those who immigrated to the US, who made aliyah to Mandatory Palestine, and those who survived the Shoah. These essays reach back to the writers' childhood memories, to teenage years, to adulthood, and cover a variety of insights about the childhood lore, teenage pranks, individual characters, the economic life, occupations, religious practices, Zionist youth groups, governing structure and day to day life of the towns' residents, and much more. Insights such as these are scattered throughout the memorial book in various essays which often touch on more than one of these themes.

What follows here are reflections that didn't make it into the Memorial Book but which help fill out a picture of these places. [1]

***

Memories of Mlynov ~1904–1907

Photo Courtesy of Eileen Sherr

Clara Fram, youngest daughter of David Hurwitz and Bessie (Demb) Hurwitz, was born in 1902. She wrote her memoire in 1980 which included memories of Mlynov from the period 1904–1907 before she migrated with her family to Baltimore. To date, these are among the earliest recollections of Mlynov life in this period that I have found and constitute an important document for imagining life in Mlynov at the time.

Excerpt 1: Mlynov Through A Young Girl's Eyes

This first excerpt points to a number of relevant themes as seen and remembered through the eyes of a five-year-old child including: the intimacy of village life, the centrality of Shabbat and religious practice, the practice of men ritually bathing (mikvah) before the Sabbath, the nicknaming or caricaturing of individuals based on their appearance or occupation, including her mother who was called "Pesse the American" because her husband was traveling back and forth to America, and the overall impression for Clara, looking back at least, that things are about to change for this small town. It is also interesting to note that, according to Clara's memory, most of the women of the town could not read and that they would gather in her house on the Sabbath, and at the age of five Clara read outloud to them in Yiddish the passages from the weekly Torah portion. These mundane, day in the life kind of memories, are precious and contrast with the turbulence of the times, which led her aunt and uncle to leave for America before she was born, and her father to commute back and forth from Mlynov to Baltimore.

Clara writes:[2]

Do you want to travel and visit a small town or “shtetil” in Poland or Russian Ukraine, about which the famous writer Sholem Aleychem, speaks in many of his works? Then come with me to the little town, “Malynov,” where there live about six or seven hundred Jews; only Jews, except the lord of the manor, the “Count” and his family, the doctor and his family, and a few other ordinary Christians who might be handy [to act as a Shabbas Goy] on the holy Sabbath.

We are traveling not by a car or train, but with a horse and wagon! Life in this townlet is very pleasant, since the inhabitants know each other well. Each housewife practically knows what the other is cooking. Life in this town is so intimate that nick-names describe some of the people, caricatures not by pen and ink on paper, but by word of mouth. For instance, there is “Chaim, the Long One,” a very tall fellow, skinny as well, and very lazy; he just doesn’t want to work. And then there is Moshe, the water-carrier, a man who is seen daily on the streets, two buckets of water suspended on a rod across his shoulders, with which he fills the water barrel each housewife has in her kitchen.

And, there is Reb Henoch, worthy Rabbi of the town, a scholar greatly respected; but he has evidently failed to note that life has been changing perhaps advancing. For there he is on his way to the synagogue, dressed like George Washington; George Washington with a beard, a long silken coat, short trousers, long white stockings and low shoes. Another well-known man in the town in Shimeon Melamed, the Hebrew teacher, whose assistant can be seen, most of the day, carrying on his shoulders, to the class, protesting pupils, some even crying, but each one equipped with a bagel for comfort.

And, in the adjoining house lives [Clara's mother] Pesse the American, a name given to her because her husband keeps going to America and returning, because he doesn’t want to raise his children in the “traife” [unkosher] America.

And, if you are a little girl in the house of Pesse, the American, you live in a wonderful spot; the Synagogue is across the way and today is an exciting day, for it is Friday. And while you are playing with mud pies that you place in an opening or aperture in the wall left by a loose brick, like your mother does in the house with the chollas for Shabbos, you watch and you listen, for you know soon they will come. And, suddenly there they come; singly, by twos and by threes, carrying clean underwear on their shoulders, the men, the Jewish men of the town. “They are going to the ‘Merchatz’ (ritual bath house)” your mother says. But you know! You also know that in the afternoon they will return; and truly, there they are, their dirty underwear on their shoulders, their faces shining, ready for the Sabbath!

And tomorrow! It is the Sabbath. And, if you are that little girl in the household of Pesse, the American, today is the most exciting day. The Synagogue, as you know, is across the way. You watch the men entering via the main door to the left, while the women use the staircase on the right that leads to their balcony in the synagogue. And, during the service, when the men below are engaged in the reading of the Torah, the women use the Yiddish translation of the Bible, call the “Teich Chumash”, reading the portion of the week. But there are many women who cannot read! Never mind. They go down the staircase into the street and across the way to the house of Pesse, the American, because they know that there sits a little girl of five on the floor, as there are not enough chairs, her mother’s teich-chumash on her lap, and she is reading the portion of the week in Yiddish for the women seated around her who cannot read themselves. That little girl was me!

Mlynov on Shabbat in front of the home of Khaykl Shnayder, the ladies' tailor. Original courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt and Irene Siegel.

Mlynov on Shabbat in front of the home of Khaykl Shnayder, the ladies' tailor. Original courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt and Irene Siegel.Excerpt 2: Daily Life in Mlynov

This second excerpt from Clara's memoire gives a sense of what daily activities of a woman of the town may have been like and how they appeared to a young girl. Clara's memories are infused with the wonder of a young girl recalling daily domestic life, but at the same time, point beyond her home life to a larger world and broader trends impinging on life in the village, such as her grandfather coming to visit and inquiring news of her father and brother who were already in America, and memory of the non Jewish woman who dyed eggs for Clara for the holiday of Easter (I wonder how Clara's mother felt about that), and the Russian soldiers who came to town and were looking for lodging, but who were refused by Clara's mother, lest her pretty daughter Minnie should become pregnant like another young girl in the village.

Especially precious is the memory of Clara's visit to her cousins, the Shulmans in the Count's forest, and being told by a servant girl about the "birds and the bees" though she didn't realize what she was hearing until much later in Baltimore. Clara thought the story irrelevant to her since her father was not around but in America. We can sense too the suffocating nature of the town, that gossiped about the fifteen year old girl who got pregnant, a story Clara overheard, and in the story that Clara's sister Minnie could no longer date a boy from another town because he was tainted by a cousin who had converted away from the faith. Losing one's Jewish identity was apparently thought to be contagious. But there are also wisps of change hinted at too, especially in the stories about Clara's sister and grandmother, Rivkah, arguing over who would get to read the Yiddish translation ofthe Count of Monte Cristo during the week. Apparently Rivkah's husband, Israel Jacob, preferred her interest in translated literature to her study of religious texts, since she used her knowledge to argue with him about the sacred texts. Hints of the Haskalah (enlightenment) are evident too in Clara's recollection of her grandfather, Israel Jacob Demb, and his Lithuanian son-in-law, Tsodik Shulman, talking about Tsodik's uncle, Kalman Schulman, the famous Haskalah writer. The outside world beyond Mlynov was peaking in through these early childhood memories.

Reflecting on her mother, Clara writes:

She herself was always occupied with her garden behind the house, where she grew potatoes, beans, carrots, radishes, cucumbers, etc. I mention these details because my mother so loved her garden, weeding and all; and it was her garden that provided much of the family’s food, plus her baking every Thursday night. [P.S. Among her favorite reminiscences was, always, that giving birth to me was so easy and quick, that “she almost lost me among the cucumbers.”]

Friday mornings, my mother greeted us with the wonderful hot “popalek”, the round flat roll (about three inches in diameter) she baked as a bonus for us children.

Beyond my mother’s personal, rather extensive, garden that she and the children worked, there was a very large field for which she engaged a neighboring peasant to work, his pay being half of what he produced there. Much of what was grown was stored in the cellar under the house, but the beans! The beans! The beans kept us busy all winter, because when the growth was dried by the sun in the field, the entire bean crop was pulled up and brought into the house. We all pitched in shelling the beans! My mother had, lovingly, given me the responsibility of tending to the peas in the garden. The blossoms were so lovely, and the peas could be eaten even raw.

My sister Minnie was a tall, beautiful girl, with long, dark hair she could sit on. She was proud of her looks, even to the point of using face powder that came in the form of small, conical bits. She took care of us two little girls, Rose and Kayla [Clara]. It was she that took us walking while she followed behind us, sometimes accompanied by a young man. He was the hairdresser and barber whom she asked for advice about my hair that was plain and straight, while Role had beautiful, long curls.

Rose was a well-covered, rosy child, while I was small and pale. Seeing us together, people would stop and remark, “What a beautiful child!” meaning Rose, whereupon Minnie would say immediately, “Ab, but she is smart!” pointing to me. Rose, even as a child, was so attractive and aggressive that my mother, in her reminiscences, even recalled a young man who happened to be visiting once remarking, “I’d like to put a deposit down on her!”

My grandmother didn’t live very far from our house, and my mother saw to it that her needs were taken care of. It was my sister Minnie who would wash and iron her clothes and deliver them to her regularly.

At times, my grandmother Rifka [Demb] would visit us on Saturday afternoon and take us children to the nearby countryside and show us various herbs growing that she told us the Lord had put on earth for us as medicine.

My grandfather [Israel Jacob Demb], when he came wanted to know what news my mother had heard from her husband, my father, as well as my brother Yitzchak who had left to join him in America.

I remember my mother once going to Dubno to buy some goodies to enhance the coming holiday, Purim. She returned with various small items, like flowers, little tables, little chairs made out of an edible substance (now known as “marzipan”)! These special items were meant for us children as well as to add to her own bakings for the “Shalach Mones” (sending of gifts) plates she sent to friends. At the same time, she brought me a pair of little red shoes I would not take off when she took me to bed.

Once a basket of colored eggs was sent to me, the “little one”. My mother said it was her friend Zocia, (the Gentile Polish woman who lived diagonally across from our house) and who sent me some eggs she had colored orange by boiling them with onion skins for their Easter holiday

There was a Russian school somewhere in the area. Once Minnie tried to enroll us children there. They accepted Rose, but they said I needed a nurse, not a school. However, when Rose studied her primer, I listened in and endeavored to learn, especially the last page which was in Greek, evidently a prayer, since the Russians were Greek Catholics.

Frequently, our cousin Hertz Shulman, a youth of about seventeen, a student in that school, would stop in our house to study, memorizing his work, while walking back and forth in the room with his book. We knew he was the son of my Aunt Pearl [Pearl Malka (Demb)] and her distinguished husband [Tsodick Shulman] whom my grandfather [Israel Jacob Demb] was delighted to have marry his second daughter. This man had arrived in Mlynow from Lithuania, well educated, rolling his R’s when he spoke Yiddish; an emancipated, proud Jew, resembling one’s image of Tolstoi, and possessing books in Hebrew and Russian, as well as Yiddish translations of French novels. He also subscribed to a Yiddish newspaper, and would talk to my grandfather about his uncle, the famous Hebrew writer, Kalman Shulman.

My grandmother Rifka (Gruber) Demb was especially attracted to Yiddish translations of the French novels. This could have been a relief to her husband, my grandfather, because he was known to have said once, “Blessed is the man whose wife doesn’t even know the ‘Alef-Bais’, the Hebrew Alphabet”, because she frequently took issue with him in his Biblical and Talmudic studies.

Years later in Baltimore, my sister Gulza told me she and grandma had almost weekly arguments about the "Count of Monte Cristo" Grandmas was reading only on weekdays because on Shabbos she studied "Perek", and the "Chapter" - (the assigned weekly chapter in the "Ethics of the Fathers"). Gulza was begging Grandma to let her have the book for Shabbos only, but Grandma said "No" every time, and she said Gulza could have the book only when she, Grandma, was finished with it."

A visit with my Shulman cousins [Pearl Malka’s kids] in their forest home was always exciting. Their father was the important manager of the entire forest. My recollection of their beautiful mother, my mother’s sister, was that she wore a sweeping “pin-yar” (peignoir) and was generally reading books.

I was about four or five years old on this particular visit when I found myself in the custody of their servant girl together with my three cousins [likely the youngest three, Sarah, Pauline and Clara Shulman] between the ages of four to seven. The girl was to take us into the woods and tell us some stories. One of the stories appeared rather strange to me. It was about what mamas and daddies do with each other, and she vividly illustrated on her own body how they go about it. There was no daddy in my house [David her father was in America], so why not wait for another story, a prettier one, I thought.

It wasn’t until I was in the sixth grade in Baltimore that some of my chummy classmates, in their own way, clarified that confusing tale I heard in the woods.

Some things that my mother and my big sister Minnie would discuss were not meant for my ears, but since I was a quiet, introspective child, I remember some highlights. For instance, I knew there were young scholars from out of town studying in the synagogue and they had no means of support, so they “ate days”, meaning each boy knew a definite schedule where he would eat Mondays, where Tuesdays, where Wednesdays, and so forth; also where he was to lodge.

Also, I must have been five or six years old when I heard my mother declare “not me, not in my house—I have girls!” It seems that the town was being overrun by Russian men who had come to work on some new project. They all needed room and board and would pay well. Here was a chance for a household to make money. In one Jewish household my mother and Minnie and the whole town knew, their attractive 15 year old red-haired daughter, evidently fraternizing with their Gentile roomer, was “showing evident”. . . . . . . to the extent that in a very few months she was spirted away to be taken care of. Her mother lost her mind.

My sister Minnie had a very handsome young gentleman friend who would come from a distant town to see her. I remember him well because he always gave me a dime (or whatever that small coin was) when he left. I knew Minnie was planning to marry him, when all of a sudden my grandfather, who was evidently investigating this fine young man came to put an end to all this; he had found out that, to be sure he was a fine fellow, but there was “meshumad” [an apostate] in his “mishpacha”. There was a blot on his family. A cousin of his had become converted.

Here, I should mention the whereabouts of my eldest sister Gulza who had married the young man Lazer Mazuryk [Louis Maser in Baltimore] when I was about two and a half years old. They lived in another town called Berestechko, closer to the border of Austria, which feature was evidently an asset in business.

I remember, for a certain holiday, they came and fetched me to visit them for a few days when I was about five. I think they wanted to fatten me up, or else why would Gulza have cooked the fish in so much milk and butter? My stomach rebelled; I lost it all. However, on another day, going with Lazer to visit his cow so I could watch him milk it, was wonderful! In my mind’s palate, I can still taste the delightful, warm milk that was in the cup Lazer had brought along.

On that same visit I remember Lazer pretended to confuse me in my reading of “Payers after Eating”. When I was reciting one paragraph after another, he would interrupt me, saying, “You don’t recite this one today.” And I would answer haughtily, “Is that so? The paragraph mentions the very holiday. Today is that holiday!” [3][2]

"The Swamp" on Deinka Street. On the left: the Daulik Synagoguge. Photographed by A. Harari. Memorial Book, p. 25

"The Swamp" on Deinka Street. On the left: the Daulik Synagoguge. Photographed by A. Harari. Memorial Book, p. 25 Batia Berger Milking Cows. Mlynov Memorial Book, p 75. Courtesy of Aaron Harari.

Batia Berger Milking Cows. Mlynov Memorial Book, p 75. Courtesy of Aaron Harari.

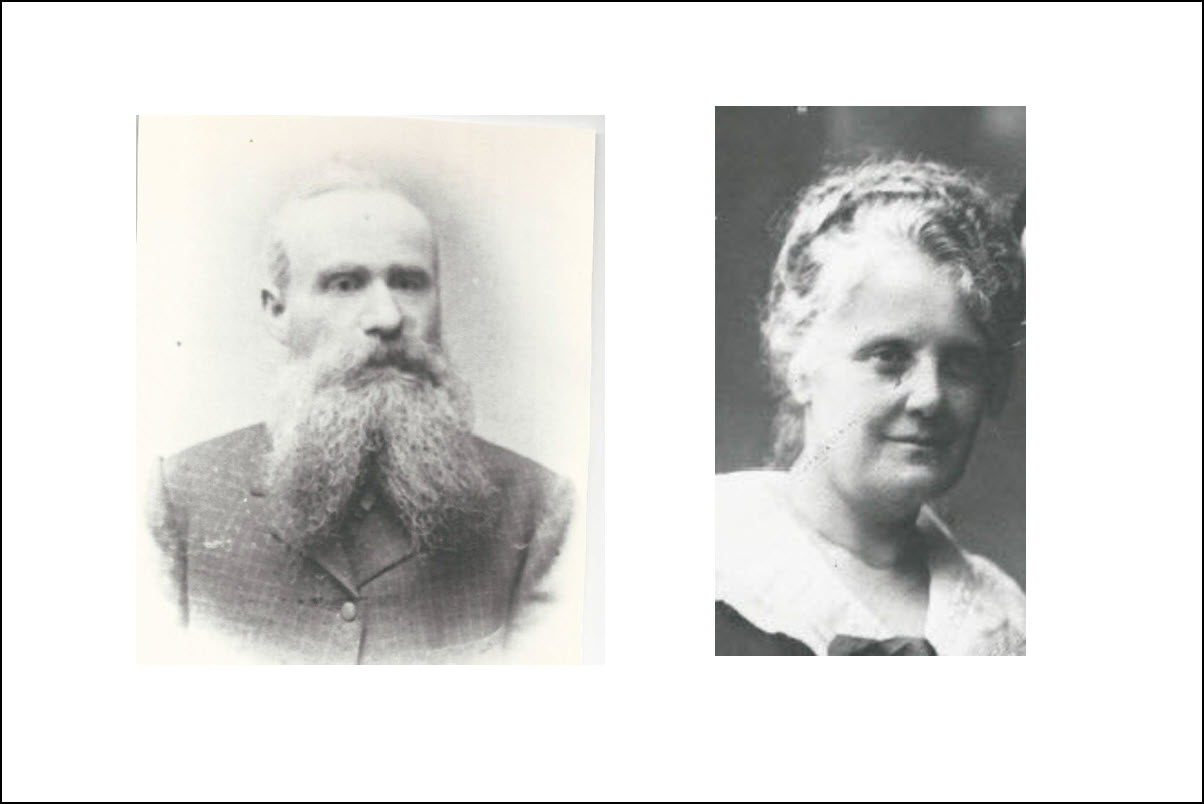

Clara's grandparents, Israel Jacob Demb and Rivkah (Gruber).

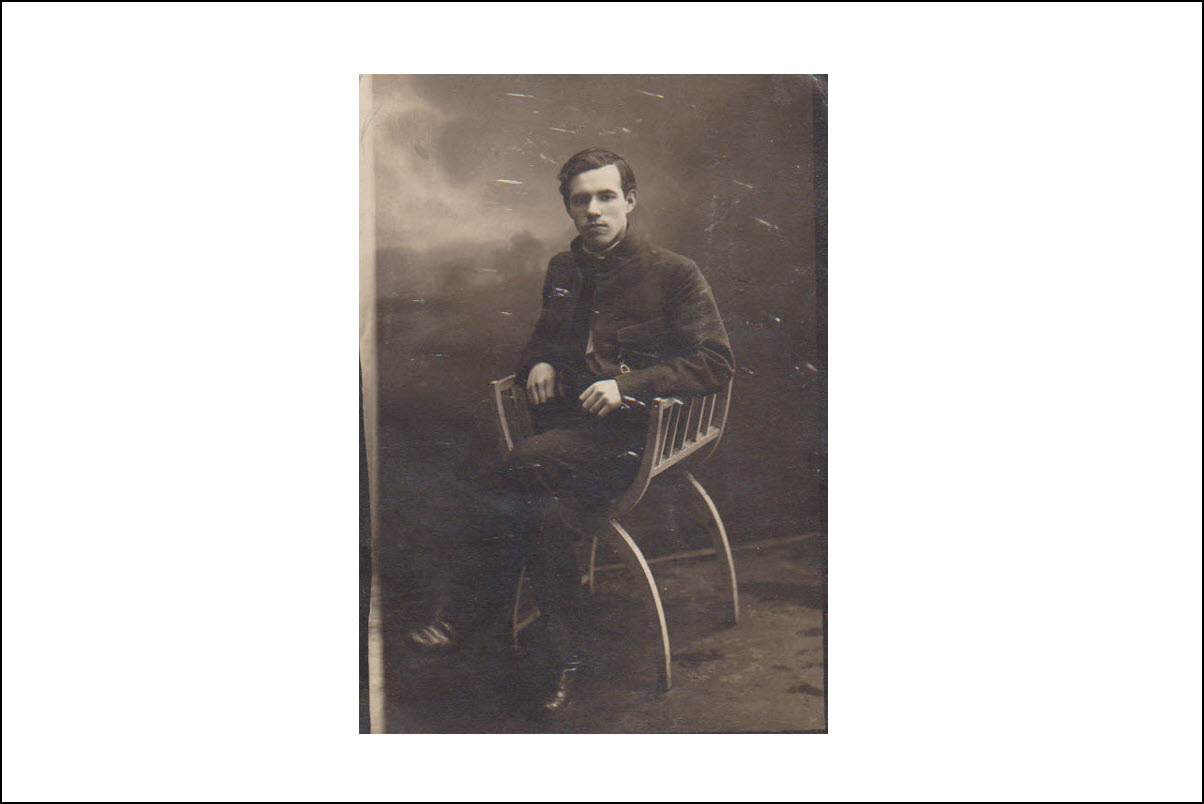

Clara's grandparents, Israel Jacob Demb and Rivkah (Gruber). Clara's cousin, Hertz Shulman circa 1913

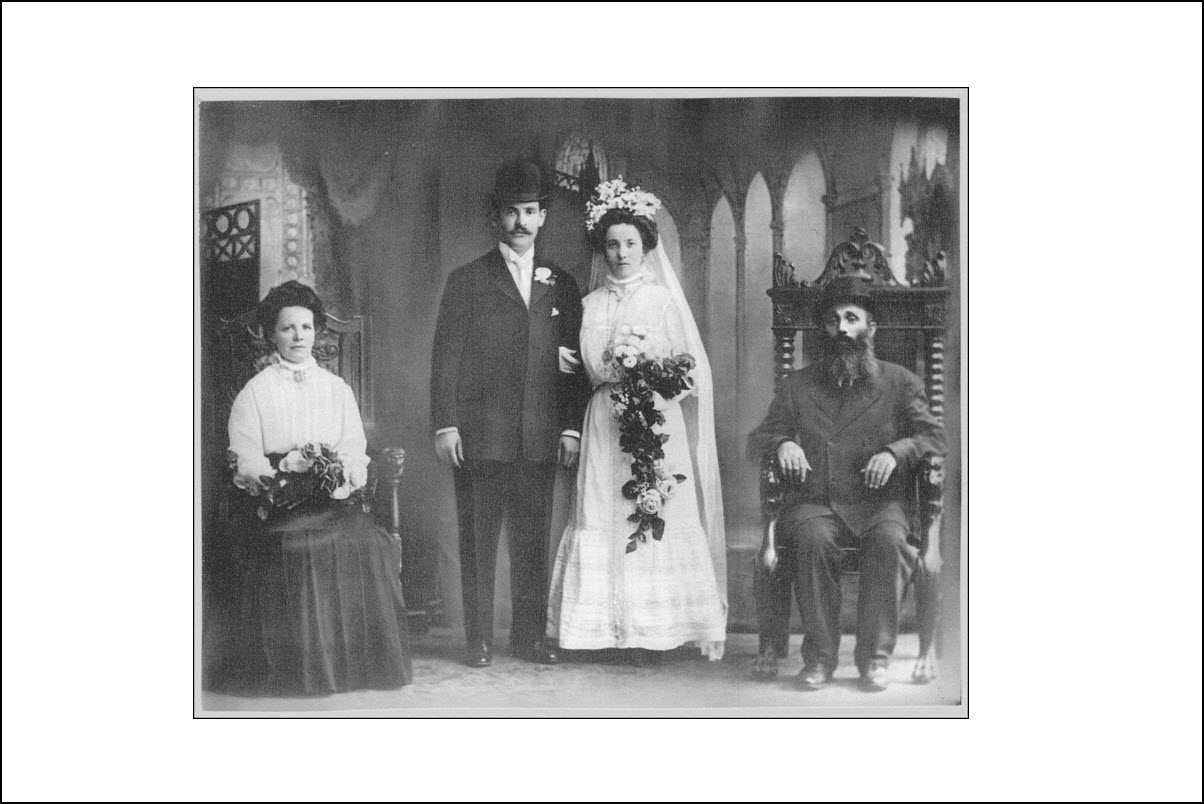

Clara's cousin, Hertz Shulman circa 1913 Tsodik Shulman (before 1921) and Pearl Malka (Demb)(~1921). Courtesy of Ted Fishman.

Tsodik Shulman (before 1921) and Pearl Malka (Demb)(~1921). Courtesy of Ted Fishman. David Rivitz (Hurwitz) and wife Bessie (Demb) 1910 in Baltimore. Courtesy of Carol Engelman.

David Rivitz (Hurwitz) and wife Bessie (Demb) 1910 in Baltimore. Courtesy of Carol Engelman.***

Sonny Goldseker's Story

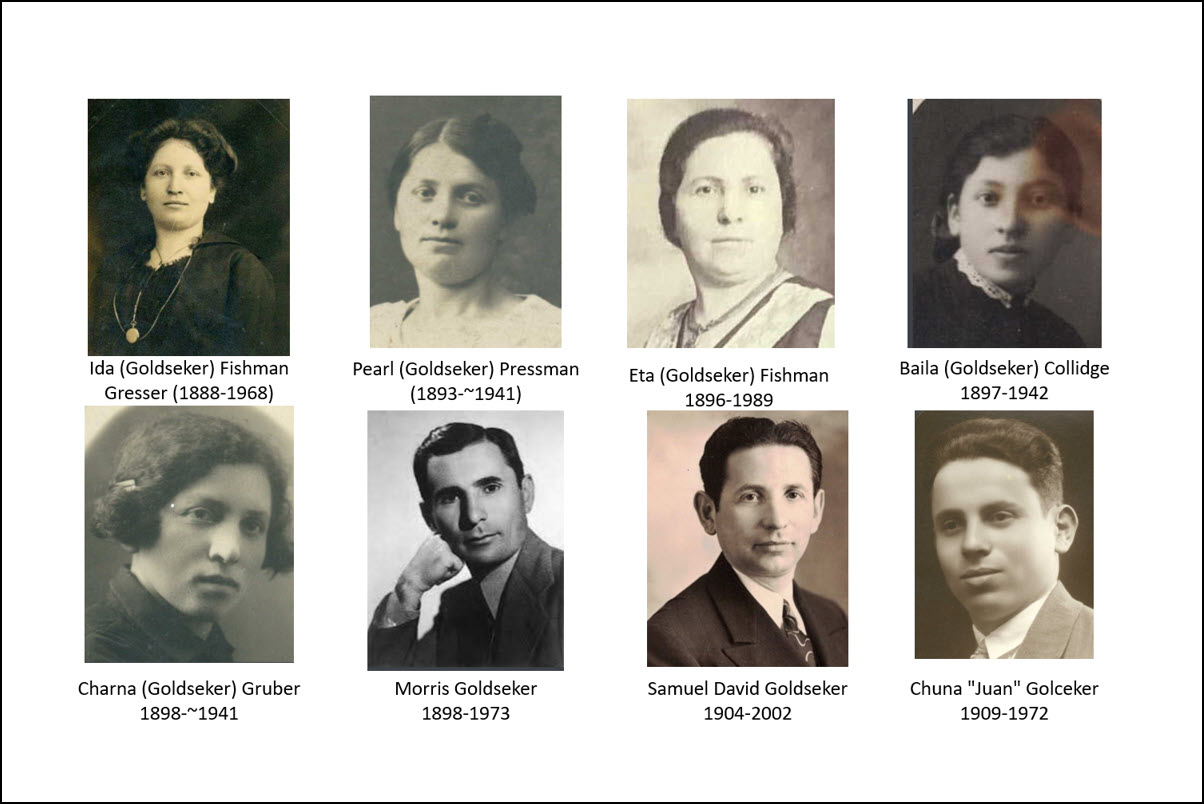

Shiman and Anna Goldseker's Family in Mlynov. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt.

Shiman and Anna Goldseker's Family in Mlynov. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt. Adult Children of Shiman and Anna Goldseker. Photos courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt / collage by Howard Schwartz

Adult Children of Shiman and Anna Goldseker. Photos courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt / collage by Howard SchwartzAs told by Audrey Goldseker Polt, written in 2019 for the Baltimore "Gathering of Mlynov Descendants," August 31, 2019

My father was born in the town of Mlynov on September 22, 1904, the son of Anna Fishman and Shimon Goldseker. The family name, Goldseker, was spelled "Holzhaker" by some family members. Dad was named David Shlomo Goldseker, in memory of his uncle, David Fishman, his mother's brother, who died several years before Dad's birth. Dad's family called him "Zeen," meaning "son" in Yiddish, instead of David in order to ease the deep sorrow his mother experienced following her younger brother's premature death. Dad's family and old friends, still call him Zeen or Sonny to this very day.

Mlynov. I knew my father came from there, but I had no idea where it was located. Did he come from Poland, from Russia? I could never understand how he came from two places. What I do know is that those early years raised in Mlynov deeply shaped who he was until the day he died in 2002, at the age of almost 98.

My father did not speak a great deal about his childhood in Mlynov because they were painful memories. I did not learn the details of his story and his journey to America, until I became a professional album maker in my 50s and I started to ask a lot of questions. He was already 90. I vividly recall that my dad wept whenever he did speak of his family and lantzmen from Mlynov, his journey to America, and ultimately the loss of all those who remained in Mlynov through World War II. [3]

My father said that in Mlynov, pogroms constantly threatened the lives of the Jews and described how the Goldsekers were driven from their home several times. At age 19, Dad concluded there was no future in this small town and he decided to follow the path of his older siblings, Ida and Morris, who left Mlynov. His father was heartbroken, as my father was the third child to leave their home for America. Sam's mother, had died about nine years earlier. My father always broke down whenever he described their parting. They knew they would never speak or see each other again.

Since the Polish army conscripted young men at an early age, it was difficult for my father to leave the country. He described walking barefoot an entire day to get to the next town in order to obtain his birth certificate to verify his age and secure his papers. Because the United States enforced a strict immigration quota, my father was forced to travel to South America. Later, his brother Chuna made the same journey, but remained in South America, married and had a family there. Ultimately, in the 1960s, Chuna's son Simon came to America and resided in Baltimore, Maryland.

Sam's first destination was Argentina, where he had a fellow lantzman. Unable to obtain a visa directly, he traveled first by train to Danzig, Germany, and then by ship to Montevideo, Uruguay. He managed to gather five dollars, a loaf of bread and a coat to serve as his blanket at night. He finally reached Montevideo. Alone in a strange country, homeless, destitute, and unable to understand or speak any language other than Yiddish or Russian, my father somehow made his way by boat into Argentina.

Not knowing where to go, what to do, he walked all night, until he reached a city, then traveled 24 hours on the train until he reached Buenos Aires. The following morning my father awoke at 5:00 a.m., bought a Yiddish newspaper, and started looking for work. He found a clothing manufacturer who had placed an ad in the newspaper. Dad stood in line with several young boys and waited until the business opened its doors. Dad explained, "By luck, they selected me!"

The business was operated by a Jewish man who took a liking to him and fortunately spoke Yiddish. Dad had meals at the home of the owner of the business, but he slept at the factory, using the cutting table as his bed, and the stack of material for the next day's cutting as his mattress. After Dad worked there for a year, he was able to save some money. He still had hopes of joining his sister and brother in Baltimore. Because of the U.S. quota, Dad had initial difficulty securing entry into the country. He contacted his brother Morris who was already succeeding in the real estate business and was able to help. A $500 loan paid for the trip to North America and ensured he would not be turned away as a pauper.

After residing in Argentina for about two years, Dad managed to secure passage to the US. He traveled second-class on a ship for 23 days, seasick and sleeping most of the time. Because he had been in Argentina long enough, and had money in his possession, Dad, fortunately, did not have to be held up at Ellis Island with other immigrants, who were suspected of being a "Likely Public Charge." Dad recounted, "By luck, I quickly got through into the United States; the woman who was next to me did not get through."

[Listen to Sam recall what happened when in New York.]

Years later my father told me about a lantzman in Argentina whom he called "Etool." He had a photo of him and had heard that Etool also came to Baltimore and that his son owned the Cross Keys Pharmacy in our area. He asked me if I would try to locate him. After several attempts of calling Cross Keys Pharmacy and not knowing his actual name, I failed to locate him and I gave up.

Three years after my father died in 2002, I had a gathering at our home for my husband's side of the family. My husband Leslie's cousin brought his "lady friend," Esther, to the get together. She had worked at the Cross Keys Pharmacy and recognized me as a customer. I thought perhaps she might have known the owner. She told me that her deceased husband, Martin Deming, was the owner of the pharmacy, and identified my father's photo of Etool as her father-in-law, Julius Deming. "But," she said, "he lived in Argentina when that photo was taken." I then told her that is where my father met him. My father would have been thrilled to meet the family of his lantzman and I was sad that I hadn't been more persistent in my investigation.

[In Baltimore,] my father worked seven days a week in his grocery store with a half day free on Sundays. He never missed stopping by his lantzman's store, the Shuchmans, perhaps to visit, as much as to shop. I vividly remember his taking me to his sister Eta's every Sunday and to his aunt, his mother's sister, Sara (Fishman) Schwartz (my connection to Howard Schwartz). She was one of the sweetest people I knew, Tanta Sora. That was my father's routine; family and his strong ties from home were very important. If he were alive today he would be overwhelmed to see a room full of family and lantzman (like the one that gathered in Baltimore for the Mlynov Descendants Gathering, August 31, 2019).

***

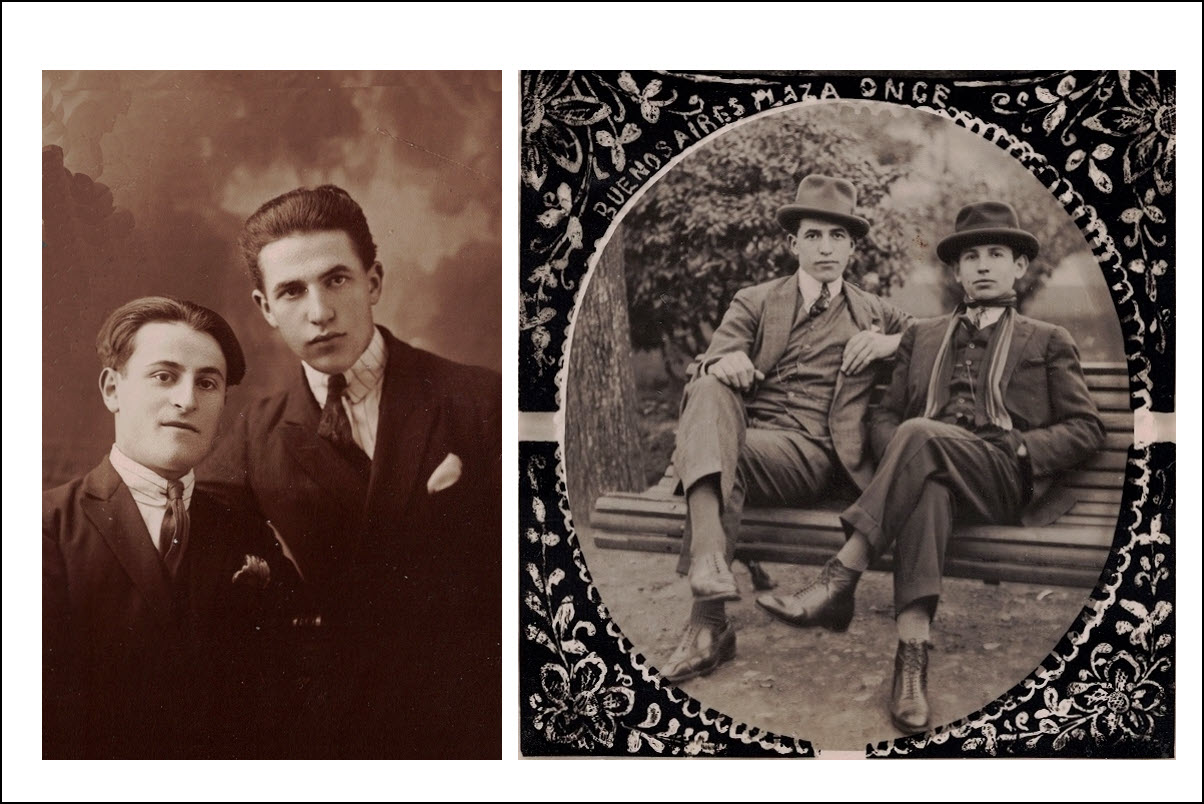

Sam Goldseker with Mlynov Friends in Buenos Aires 1924

Sam Goldseker with Mlynov Friends in Buenos Aires 1924

left to right: Samuel Goldseker, Muttle Mazlich, Woodluck, Woodluck's brother, "Etool" (Julius Deming), Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt. Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires (from right to left): Sam Goldseker and Muttle Meizlish, Muttle Meizlish and brother, Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt.

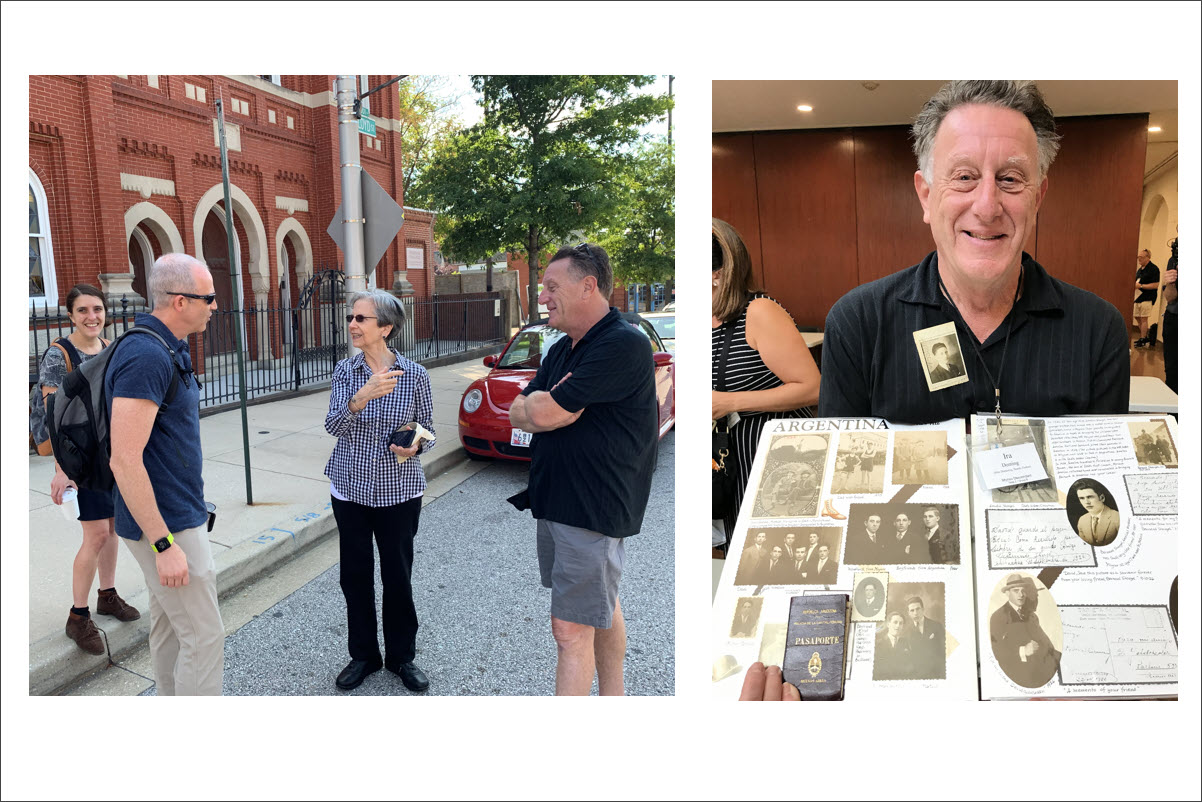

Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires (from right to left): Sam Goldseker and Muttle Meizlish, Muttle Meizlish and brother, Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt.On August 31, 2019, Audrey met Julius Deming, the grandson of her father's close friend "Etool" at the Mlynov Descendants Gathering in Baltimore. They were introduced by Howard Schwartz, who had figured out that Audrey's father had been best friends of his third cousin's grandfather. That is another story.

Sam Goldseker's daughter, Audrey Goldseker Polt (center) and grandson Richard Polt (left), meeting Ira Deming, the grandson of their father's close friend "Etool" from his days in Buenos Aires. Courtesy of Howard Schwartz.

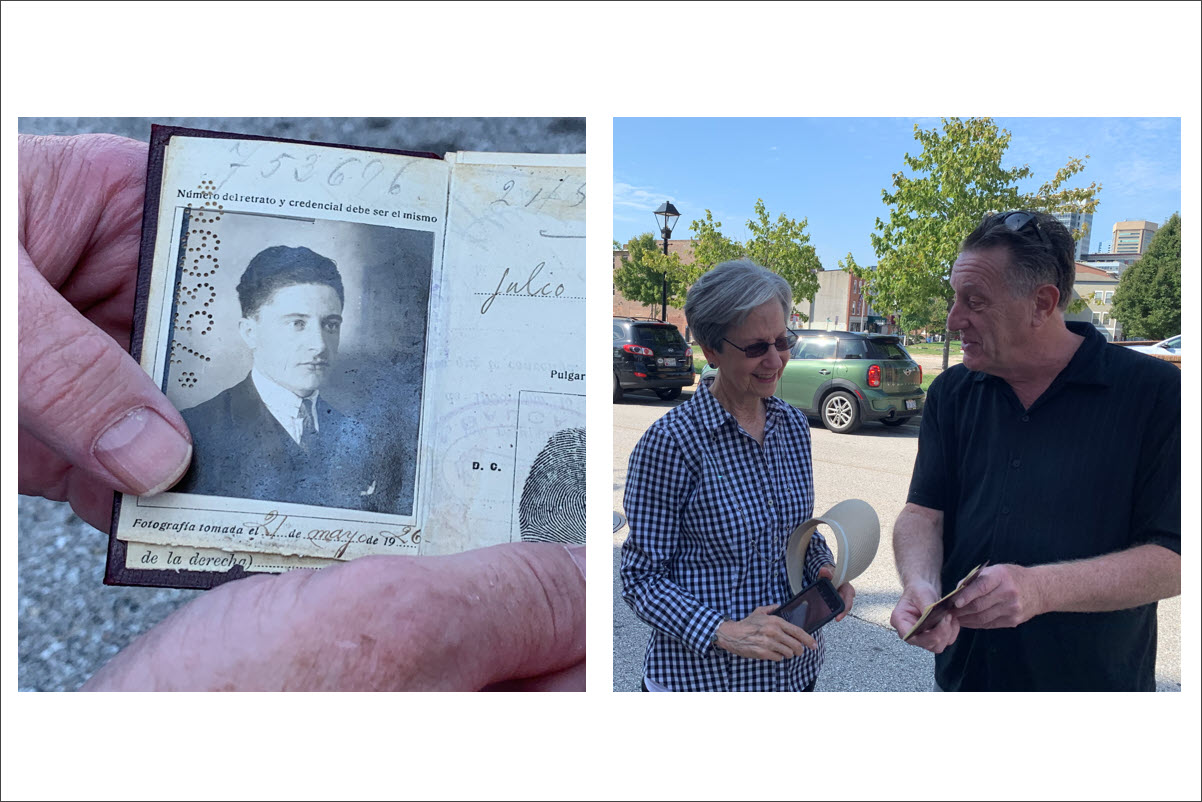

Sam Goldseker's daughter, Audrey Goldseker Polt (center) and grandson Richard Polt (left), meeting Ira Deming, the grandson of their father's close friend "Etool" from his days in Buenos Aires. Courtesy of Howard Schwartz. Ira Deming showing Audrey Goldseker Polt, the immigration papers of his grandfather, Julius Deming, who entered the United States in 1926 and was close friends with her father in Buenos Aires. Courtesy of Howard Schwartz

Ira Deming showing Audrey Goldseker Polt, the immigration papers of his grandfather, Julius Deming, who entered the United States in 1926 and was close friends with her father in Buenos Aires. Courtesy of Howard Schwartz***

NOTES

[1] The following excerpts are from Clara Fram's memoire, "This Is My Story: I Write And Speak Of Myself. Part of a Continuing Education Through Senior Seminars, Amalie Sharfman, Instructor.(Hereafter Fram, "My Story"), 1982, p. 1-2. Quoted with permission of the Fram descendants. ↩

[2] Fram, "My Story" p. 4–5 ↩

[3] Audrey: "I thank my older first cousins Irene (Siegel) and Selma (Bacher), Fishman descendants, and my brother Sheldon who filled in many details." ↩

***

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz

Updated: July 2024

Copyright © 2021 Howard I. Schwartz, PhD

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History