-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Mlyniv, Ukraine

"Mlinov", "Mlynov", "Mlynow", "Mlenow", "Mlynów" [Pol], מלינוב [Heb]

Lat:50° 512390', Long: 25° 607000'

The Search for Mlynov (מלינוב) and Mervits (ו מ ר ו ו י ץ )

A collage of Mlynov ancestor photos gathered from descendants in Baltimore

***

Buried under the rubble of time, forgotten by the vicissitudes of history, lie two small towns, both shtetls that until recently have been lost to memory, especially to the memory of families who ended up in the English-speaking world. They were sister towns, no more than a mile apart, and their economies, cultures, institutions, and families were so intertwined with one another that some residents later hyphenated the town names, as if they were one place. In the end, residents of the two towns were liquidated together in an area along the road between them.

The larger of the two towns, Mlynov (also spelled "Mlinov" and "Mlynow," among other variations), still exists on maps today as "Mlyniv, Ukraine," close to Dubno. There was a small Jewish community residing there not long after the area became part of Tsarist Russia in the Second Partition of Poland (1793). The smaller of the two towns, called Mervits ("Muravica," "Muravista," among other variations), no longer appears on maps today and its prior location is just outside the existing border of its larger and still existing neighbor.

This web site is dedicated to the history, people and character of these two Jewish communities ("kehilla") and their descendants. This reconstructed history is based on records, stories, memories and photos, of those who left and those who stayed behind. The information that appears in these pages is based on original research, oral histories, interviews, historical studies, and memoires. Descendants of Mlynov and Mervits famimilies, living now for the most part in the US and Israel, contributed family photos and stories to this effort. Each family had a piece of the larger puzzle.

Mlynov and Mervits were small towns ("shtetls") off the beaten tracks in Western Russia and later Poland. They first became part of Russia and the Pale of Settlement during the Second Partition of Poland (1792–1795) when Russia acquired vast parts of Poland. This was the first time Russia had a substantial Jewish population under its control and the result would be an ongoing struggle in Russia to define how this unusual population should be governed. The struggle to define a policy for the Jews comprises the history of Russian Jews in the 19th and early 20th century.[1]***

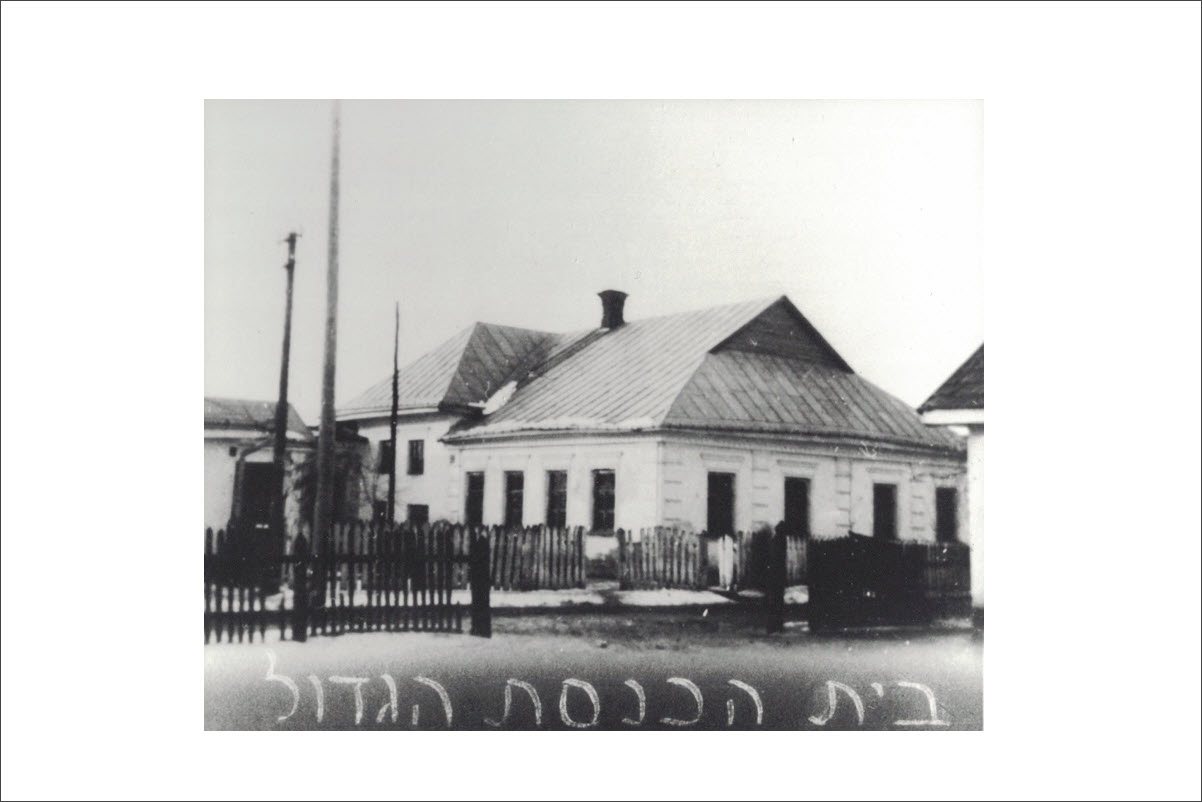

The largest cities near Mlynov are Dubno, Lutsk, and Rivne (Rovno). Mlynov is located on the road between the towns of Dubno and Lutsk. It is about 9 miles northwest of Dubno and 21 miles southeast of Lutsk. Mlynov is also just 50 km southeast of Rivne (or Rowno as it was called in Yiddish). The small townlet of Mervits was just one mile NNW of Mlynov and life of residents in Mlynov and Mervits were deeply intertwined via family marriages, resource sharing, culture and religion. Scenes from Mlynov. Great Synagogue of Mlynov. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt[2]According to online sources, there were 690 Jews in Mlynov in 1900 and they constituted 60.8% of the population. These sources, however, do not provide the basis of their statements and thus have to be used with caution.[3] The Mlynov-Muravica Memorial book [hereafter just Mlynov Memorial Book], which was published in 1970, cites earlier sources indicating that in 1885 there were were 62 houses, and 203 inhabitants, 38% of whom were Jewish. According to another source cited, Mlynov had a Jewish population of 209 in 1847 and 672 in 1897 out of a total population of 1,105. These sources have not been independently verified.[4].

Scenes from Mlynov. Great Synagogue of Mlynov. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt[2]According to online sources, there were 690 Jews in Mlynov in 1900 and they constituted 60.8% of the population. These sources, however, do not provide the basis of their statements and thus have to be used with caution.[3] The Mlynov-Muravica Memorial book [hereafter just Mlynov Memorial Book], which was published in 1970, cites earlier sources indicating that in 1885 there were were 62 houses, and 203 inhabitants, 38% of whom were Jewish. According to another source cited, Mlynov had a Jewish population of 209 in 1847 and 672 in 1897 out of a total population of 1,105. These sources have not been independently verified.[4].***

Russian records for the two communities in 1850 and 1858, called "revision lists" by the Tsar's government, were located, translated and appear on this website with a running commentary (Mlynov and Mervits). They provide a wonderful window into the lives of those who lived in these small Jewish communities in the mid-19th century. In 1850, there were 48 households in Mlynov with 247 named individuals, 200 of whom were still living. Eight years later in 1858, there were 64 households including 9 that were listed separately as craftmen. There were 340 names on this revision, of whom 284 were still living.

Most of what we know about Mlynov and Mervits, from family histories and memories, refers to people who lived in the period between 1850–1940 and comes from a later date; the Mlynov Memorial book, for example, which contains many recollections of Mlynov or Mervits families, was published in 1970 and thus represents memories after WWII when the atrocities of the Nazis had come to light and been understood. Thus far no records before 1850 have been discovered for Jewish residents of these towns. A small number of residents survived the Nazi occupation, and their memories have been recorded. This site is a tribute to both the families and their descendants from this place.

***

Location

Mlynov is located today in what is now Western Ukraine and spelled "Mlyniv." In the second partition of Poland (1792–1795), Mlynov and Mervits became part of Russia where they remained until WWI. Mlynov and Mervits were close to the Eastern Front during WWI and switched hands multiple times in the civil war following WWI before becoming part of Poland. Mlynov remained part of Poland until WWII. You can view Mlyniv today via Google Maps or Mapquest.

We know from memoires and oral interviews that residents of Mlynov and Mervits would visit Dubno on a regular basis. Dubno is mentioned in the memoire of Clara Fram as the larger town her mother, Pesse, visited when shopping for nice things for the holiday and the place her father disembarked from the train on his trips to and from America in the 1890s. Solomon Mandelkern spent time studying in Dubno after leaving Mlynov when he was 14 in about 1860. Immigrants and survivors from Mlynov recall walking to Dubno as young teens.

According to the census of 1897, Dubno had a population of 13,785, including 5,608 Jews. The main sources of income for the Jewish community in Dubno were trading and industrial occupations. There were 902 artisans, 147 day-laborers, 27 factory and workshop employees, and 6 families cultivating land. The town had a Jewish hospital and several chederim (Jewish schools).[5]

Lutsk is also mentioned in the Demb family story as a place where Samuel Roskes, the husband of Mollie Demb, the youngest Demb daughter, was born and where their first son was born. We don't know how Mollie Demb and Samuel Roskes met each other but the marriage suggests the kind of local mobility that was possible at the time. Sylvia (Barditch) Goldberg also recalls (in an essay in the Memorial Book) going as a young girl from Lutsk where she was born to Mlynov where her grandparents lived, to attend a memorable wedding. In 1802, there were 1,297 Jews in the town; by 1847, there were 5,010 (60% of the population); and in 1897, there were 9,468 (60% of the population).[6]

To the west and south about 25 miles, you can see Berestechko, which is where Gulza, the oldest daughter of David and Pesse (Demb) Rivitz, settled with her husband, Leizor Mazuryk (later Louis Mazer in Baltimore). In her memoire, Clara Fram has childhood memories visiting her older sister in Berestechko as a young girl and recalls how she passed through Brestechko with her mother, grandmother and two sisters on their immigration to Baltimore in late 1908. The community numbered 1,927 in 1847, 2,251 in 1897 (45% of the total population), and 2,210 in 1931 (total population 6,514).[7]

Novohrad-Volynskyi (sometimes written "Novograd" in immigration records) is about 100 miles to the east. Records indicate Mlynov-born, Motel Demb (Max Deming), his brother Simha Gruber and Simha's two sons, Nathan and Samuel, were living here for a time and this might have been the city to which some of the Mlynov population was evacuated during WWI. Motel married a woman from Novograd and their daughter Sylvia was born here. At the start of the 20th century, 10,000 Jews or 50% of the population, lived in the town. In 1919, the Pogroms in Ukraine reached Novohrad-Volynskyi, and the troops of Symon Petliura murdered 1,000 Jews.[8]

Volodymyr Volynskyi, called "Ludmir" in Yiddish, is 70 miles west of Mlynov. Ludmir was the town where the well-to-do Moshe Gruber from Mlynov headed to find a suitable husband for his daughter Rivkah Gruber when she turned 11 and was of marrying age. He brought back a fifteen-year-old named Israel Jacob ("Yisrael Yaakov") Demb. They became the patriarch and matriarch of the large Demb family in Mlynov.

It is possible that Moshe Gruber was drawn to Ludmir because of its reputation as a Hasidic center. When the founder of the Karliner Hasidic dynasty, Rabbi Shelomoh ha-Levi (murdered in 1792), settled in Ludmir in 1786, the town became an important Hasidic center. The "Maiden of Ludmir," Khane-Rokhl Werbermacher (~1806–~1888), a local woman known for her righteousness and wisdom, also became a popular Hasidic leader; numerous Hasidim gathered in her bet midrash. After she moved to Jerusalem in 1861, her bet midrash was occupied by the Rakhmistrov Hasidim. The Jewish population of Ludmir grew thanks to its status as a trade and crafts center located close to the border. Some 1,849 Jews were registered in the city in 1799; rising to 3,930 in 1847; and reaching 5,869 (about 60% of the population) in 1897.[9]

***

Notes

[1] A very detailed, and I found helpful, summary of Russian policy towards the Jews, which gives the nuances of changes under each Tzar, can be found in Antony Polonsky, The Jews in Poland and Russia. Vols. 1 and 2. The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. Oxford, 2010. These volumes give an understanding of the variability and complexity of the evolving policies and their motivations. ↩

[2] Audrey (Goldseker) Polt, a descendant of the Goldseker Family, provided this clear photo of the "Great Synagogue" in Mlynov. The others are from the digital version of theThe Mlynov-Muravica Memorial Book (translated title for the original Sefer Mlynow-Marvits . Ed. J. Sigelman, Haifa:1970. Published in Hebrew and Yiddish by former Residents of Mlynov-Muravica in Israel. A digital version of the original can be viewed online in several websites including the NY Public Library and the Yiddish Book Center. A new complete annotated English translation of the volume has been published by descendants of Mlynov families and is available online and in print. ↩

[3] Two websites record that the population of Mlynov was about 690 Jews in 1897–1900 but neither give the source of their information. See JewishGen and a website on Shetl history. There was a Russian census in 1897 and it is possible these statistics derive from that census, but that is uncertain. The citations from the Memorial Book are from pages 10 and 11 of the original and cite a Polish Encyclopedia from 1885 and the Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol. 12, written in Russian. For the translation of those pages, see Sokolsky, Mlynov-Muravica, p. 3-4. ↩

[4] David Sokolsky also cites statistics on the population of Mlynov in his book on Liba Tesler's escape from the Holocaust, Monument: One Woman's Courageous Escape from the Holocaust, 2017, 15. David writes that when Liba was born in 1912 there were 670 Jews in Mlynov comprising 60% of the population and that by 1931 the number of Jews had grown to 900. In an email to me, David indicated that when he was first researching the book in the 1970s he found these numbers in a 1910 World Almanac. I have not yet been able to verify this source. ↩

[5] See "Dubno" in Wikipedia. ↩

[6] See "Lutsk" in Yivo Encyclopedia. ↩

[7] See "Berestechko" in Yivo Encyclopedia. ↩

[8] See "Novohrad-Volynskyi" in Wikipedia. ↩

[9] See "Volodymyr Volynskyi" in Yivo Encyclopedia. ↩

***

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz

Updated:May 2024

Copyright © 2019 Howard I. Schwartz

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

***

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History