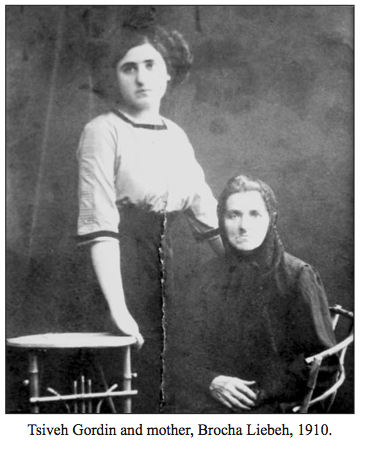

Tela Zasloff wrote a book about her grandmother, Tsiveh Gordin/Sylvia Berman, who was born and grew up in Rezekne, Latvia. Follow is a portion from the book titled Family History which also contains an excellent account of the Jewish History of the city.

The entire book can be downloaded as a PDF file by going to the Gordin Family

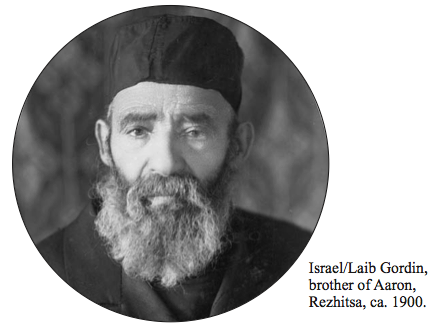

Where Grandma's parents and grandparents were born is unknown, but we do know that she and her siblings were born in the 1880s and 90s in Rezhitsa (now Rezekne, Latvia), a small town in what was then Vitebsk province in the Russian, czarist empire. We also know, from the Latvian National Registry, that two of her father's brothers, Israel/Laib and Faivish, lived in the Rezhitsa area and that Faivish was married there.

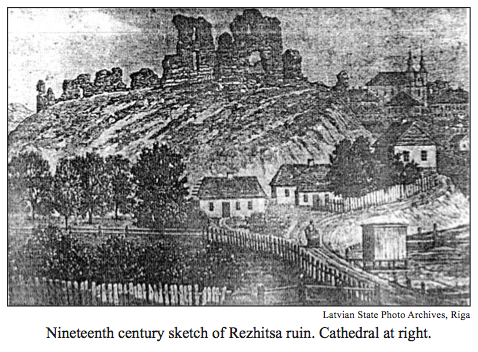

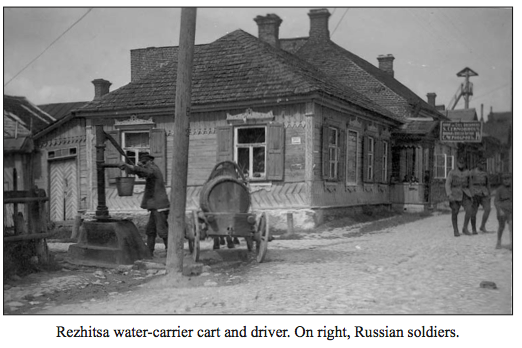

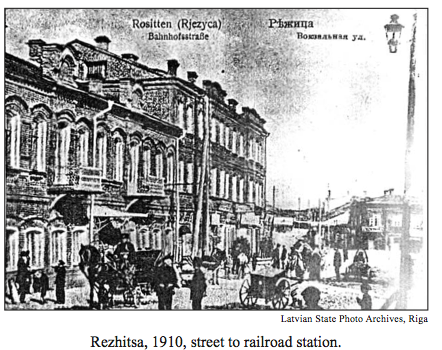

Rezhitsa was the district town of the province, at a railroad junction between St. Petersburg and Warsaw. The town's oldest historical monument is the remains of a fortress castle built in the ninth century by the Latgalians. The Jewish community was founded in Rezhitsa after 1775 by Jews who had been banished from Makashani, a village 18 kms away. They set up the Holy Ark in the Beit Midrash they established in their new town. In 1802 there were 533 Jewish inhabitants and 187 Christians in the town. In 1815 (probably during the lifetime of Grandma's paternal grandfather, Reb Hendel Gordin) there were 1,072 Jews in Rezhitsa, 90% of the total population.

The rabbi of the community from 1861 to 1900 was Rabbi Yitzhak Zioni (also known as Rabbi Itzele Lutsin). He was the son of Rabbi Naftali Zioni of Lutsin (later Ludza) and was the author of the essay "Olat Yitzhak." Beginning in 1900 two rabbis officiated in Rezhitsa: Rabbi Dusovich served the poorer members and Rabbi Haim Lubocki, the richer ones. A third rabbi, Yaakov Pollak, was appointed by the Russian government. The Jewish community established a charitable fund, a public kitchen for the needy, an organization for visiting the sick and an old-age home for the poor. By the time of Grandma's birth, in 1890, there were 11 synagogues in Rezhitsa, the largest, built of brick around 1882.

Until 1900, the children studied in Jewish schools, Hadarim, which also taught secular subjects, and in a Talmud Torah. By 1900, when Grandma was 10, most of the Jewish children attended the State elementary school, which provided four years of study for boys, and the State gymnasia, where Jews were limited to 5%. An elementary school for girls, which was the extent of Grandma's formal schooling, was opened through the efforts and donations of the Jewish women of Rezhitsa. The language of instruction in the State schools was Russian. By 1914, eight years after Grandma had left Rezhitsa, there were 11,000 Jews in the town, making up 50% of the total population.

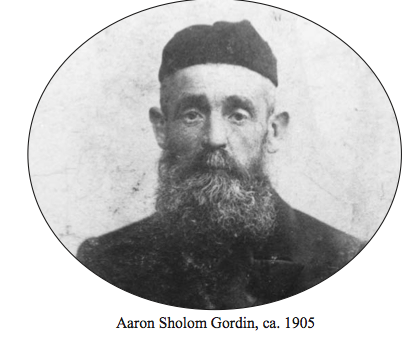

Until 1900 most of the Jews of Rezhitsa were either merchants, mainly in flax and agricultural produce trades, or general tradesmen. Many in this latter group were tailors. The Russian census-takers categorized Jewish tradesmen as "petty bourgeois," meaning lower middle class, to differentiate them from the merchants, nobility, clergy, peasants (no Jews allowed in these classes), and intellectuals not belonging to the gentry—teachers, doctors, and students, all university graduates. The lower middle class paid taxes and were recruited for the army, from which merchants were exempt. Grandma's father, Aaron Sholom Gordin, was a drayman (driver of horse and cart)-for-hire, so that, like most of his sons, was listed as a "petty bourgeois."

In 1872, Eugene Schuyler, an American charge d'affaires at the U.S. legation in St. Petersburg, sent a report to the U.S. Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, on "The Legal Position of the Hebrews in Russia." This report gives a detailed picture of the political environment in which Grandma's family was living and argues that a more just system should be put in place to integrate Jews into the population rather than isolating them. "The disabilities and exceptional position of the Israelites in Russia are based, not on religious intolerance, but on the idea that the Hebrew race 'has a natural tendency to exploit the population in the midst of which it is settled'," the author begins. He summarizes the situation of the Jews in Russia as being members of an "alien race" that owes allegiance to the czar and is subject to all of the burdens but few of the privileges of Russian subjects. On the assumption that they are harmful to the population at large, Jews were under special government supervision and were restricted in where they could live, in what occupations they could pursue, and in acquisition of property, mode of life, dress, education and manner of worship.

These regulations directly affected the mode of existence of Grandma and her family, and their attitude toward their native land. Of the 2,348,000 Jews in the Russian Empire in 1872 (3.06 % of the total population), 9-13 % were crowded into the western provinces, which kept them in poverty with little chance for improvement. For example, the many tailors in her family were kept to a minimal existence because they were among 15 or 20 other tailors in a small town that really needed only three or four. In 1835 when the Russian government experimented with inducing Jews to become farmers, they claimed that the Jews' general disposition was for "petty trade" rather than laboring on the land, although it was only the poorest, least experienced Jews who accepted the offer, and many died from lack of government assistance.

Recruitment in the army was pressed most severely against the Jews, many of them taken into the army when very young, some not returning to their families until 20 years later, and some, never returning. No Jews could become officers. In all self-governing, local institutions—like trade organizations, municipal agencies, town governments—non-Christians could constitute only 1/3 and no Jew could be chosen as mayor. Taxation was doubly or triply heavy on the Jews, on butchering kosher meat and its sale, on Sabbath candles, on manufactured goods, on estates and on the wearing of traditional clothing and hair styles. The taxes fell, in turn, on the peasantry who had to pay the higher prices asked for the goods they wanted to buy.

Therefore, Schuyler argues, the so-called harm and exploitation that Jewish merchants imposed on the Russian peasantry actually arose from the law itself.

The list of restrictions on religious rights of Jews is blatantly unjust and self-defeating for the Russian government, the author continues. Marriage between Jews and Orthodox or Roman Catholic Russians was forbidden. Protestants or Lutherans could marry Jews but the Jewish spouse had to give written promise to educate the children as Christians. "It is plain," he continues, "that any antipathy of the common people toward the Hebrew cannot be eradicated so long as the government itself marks them out as a peculiar people with whom marriage is illegal." This alienization of Jews was apparent in the regulation that synagogues could be built no nearer than 700 feet from any church, and on a larger scale, in the effect of Russian ultra-nationalist movements that provoked medieval sentiments of attacking Jews. The historical basis for restricting Jews so severely is the old Polish laws that forbade peasants to engage in trade. The Jews, cut off from farming and the professions, thus monopolized trade and fell into the position of being the go-betweens for the upper and lower classes, making their profit from each and constantly stirring resentment. But the large majority of Jews existed under "a lack of settled residence, constant change and vagrancy, lamentable sanitary conditions, a great mortality, a lowering of morality, a want of means, and an insignificant amount of profits and money saved."

Schuyler concludes: "In spite of the recent reforms, the condition of the Hebrews in Russia, massed together in the western provinces ... is growing worse and worse." The fault lies in the laws that places them in a position to be ruined. Despite the attempts at liberalization in the Russian legislation of the time, Schuyler considers it impossible to construct one Russian nation while laws existed that made Jews a separate body and that cast slurs on them. This made them "shut themselves out still more and resist all attempts to draw them into normal relations with the rest of the body politic."

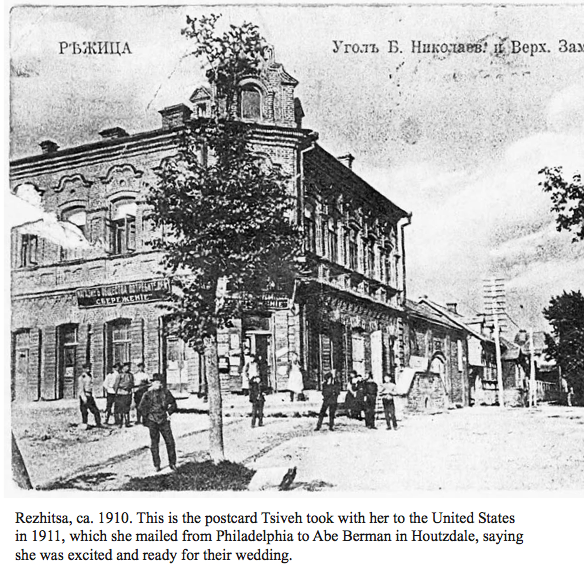

Whether Schuyler was right that liberalizing legislation would have integrated the Jews into the population and made a stronger country, this was not the direction that Russian history took. By the time Grandpa (whose family rented part of Grandma's family house in Rezhitsa) emigrated to America in 1908, and then persuaded Grandma to follow him in 1911 as his bride, life in Rezhitsa for young, enterprising Jews was at a dead end. The empire was falling apart, which always put barely tolerated minorities in an especially precarious position. For Russian Jews, international socialism was one attractive alternative to empire and Zionism was another. Grandpa was persuaded by the first and took it with him to the United States, where he continued working in the labor movement for the next 40 years.

Grandma and Grandpa came to America in a wave of Jewish immigrants, between 1881 and 1914, that reached almost two million—the large majority from eastern Europe. Irving Howe, in World of Our Fathers, characterizes this wave succinctly. Compared to other national groups, the Jewish migration was more a movement of families, showed more determination to settle permanently, and contained a higher proportion of skilled workers than any other group—the intellectuals and skilled workers increasing in number as the period progressed into the twentieth century.

Some were in mass flight from disaster and oppression in Russia, like the 1881 pogroms and the 1903 Kishinev massacre; some, especially the young, chose to leave because they were restless, frustrated by the constriction of their lives and stimulated by a Yiddish cultural renaissance; some left out of strong religious or political conviction, like the Zionists or some Bundists who fled after the failure of the 1905 Revolution. But the vast majority, Howe continues, responded to the "urgencies of their experience. . .not only the displaced and declassed but increasingly the energetic, the vigorous, the ambitious. . . A whole people was in flight."

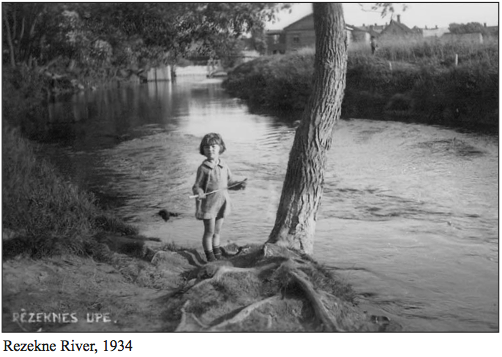

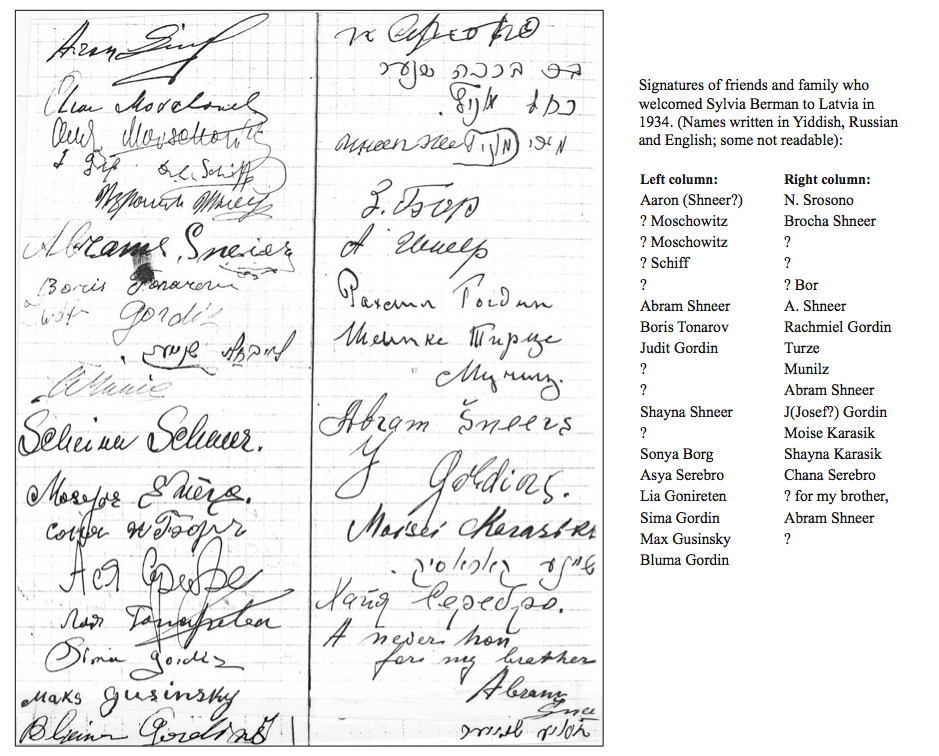

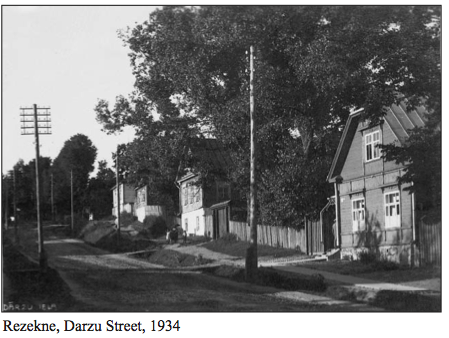

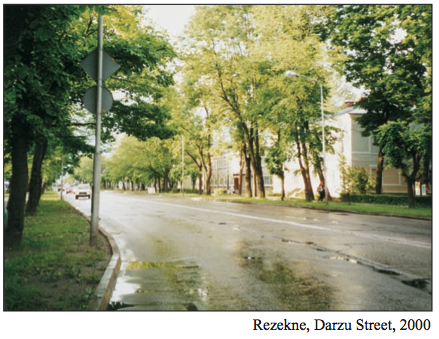

After World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1918, while Grandma was establishing herself and her family as new American citizens, Rezhitsa became Rezekne, now a small town in the eastern section of the renewed nation of Latvia. For a while, the Jews of Latvia were part of a fledgling democracy that gave Jews minority status and access to the legislative system. But by the 1930s, totalitarianism in Germany, the Soviet Union, and Italy dominated the political climate of Europe. Three months before Grandma traveled back to Latvia in 1934 to visit her family, there was the Ulmanist coup in Latvia that began to establish anti-Semitic measures similar to those Hitler was setting up in Germany.

In Grandma's journal written during that visit, there is no mention of the coup, or anxiety about the fate of Jews in Latvia. But Sima, her niece by marriage, remembers Grandma's remarking to her family that she didn't want to return home through Berlin because she could see, from the train carrying her to Latvia, boarded up shop windows with the letters "JUDEN" painted across them. It was about a year later, Sima also remembers, that Latvian Jews began agreeing among themselves that they were not going to speak German any longer.

World War II and the Holocaust claimed most of Grandma's family who remained in Latvia. The Jewish Museum in Riga documents the story. In the summer of 1940, following the German-Soviet pact, the Soviet army entered Latvia and installed a government. In mid-June 1941, after the German attack on the U.S.S.R. and imminent occupation of Latvia, Jewish property owners and officials of non-Communist organizations in Latvia, together with their families, were banished by the Soviets to Siberia. This group included some of Grandma's nieces and nephews.

On July 3, 1941, German forces occupied Rezekne. All Jewish men ages 18 to 60 were ordered to report to the market place. About 1,400 were released, about 50 were killed on the spot, and the remainder were locked in prison and then some shot to death while others were ordered to bury them. Some Jewish tradesmen were taken to forced labor camps.

The destruction of Rezekne began the second week of July. In seven days members of the auxiliary Latvian police killed over 140 Jewish men. At the end of July, Rabbi Lubocki was ordered to appear at Gestapo headquarters but instead, he went to the Jewish cemetery where he met with some of his congregants and encouraged them to be strong. They were all shot to death, including one young man who killed three Latvians before he died.

According to one version, the Jews who were left were taken to the Daugavpils (formerly Dvinsk) ghetto and most died there, the remaining transferred to the Kaiserwald Concentration Camp near Riga. According to another version, the remaining Jews were murdered at the Rezekne Jewish cemetery and at one of the old rifle ranges in the Anchupani Mountains, about 5 kms away. The final action was carried out on August 23, 1941. A group of 12 Jews who had converted to Christianity were discovered and also murdered. Those who worked for the Germans were destroyed in 1943.

In the summer of 1944, before their withdrawal, the Germans took a group of Jews from the Riga ghetto and ordered them to dig up the bodies of those who had been murdered and burn them. Then these Jews, in turn, were also murdered. In the town of Rezekne, two Jewish adults and several children were saved by going into hiding with local residents. Rezekne was liberated by the Soviet army on July 7, 1944.

Grandma's brothers Tsalel and Hendel and their wives must have perished either in mass roundups in Rezekne or in one of the ghettos. The only direct evidence we have of Tsalel's death is the testimony of his son Laib, given to Yad Vashem in Israel in 1987. Laib also reported to Yad Vashem that his wife and child had died in the Riga ghetto. We have no evidence for what happened to Tsalel's daughter, Judith, one of Grandma's favorite nieces who was a vivacious companion during Grandma's visit in 1934. Hendel's son Aaron and his daughter Doba are unaccounted for. Hendel's sons Rachmiel and Josef, and his grandson Boris were killed as soldiers in the Soviet army, after escaping into the USSR with their families right before the Nazi invasion of Latvia. Sima, Rachmiel's wife, remembers that on the day before the Nazis arrived, she pushed her children, Rachmiel, his brother Josef and her own brother onto a truck bound for the train that would take them to the village of Ochora, in the USSR. Bella, Sima's daughter, who was eight at the time, remembers a Latvian friend shouting "Fire!" to create mayhem so that her father and uncles, who had been barred from the truck by the authorities, would not be discovered.

Grandma's sister Chaya, her husband Isser and their daughter Bronya all died in the Riga ghetto. Isser and Chaya had lived well in Riga before the war, according to Sima. They owned a large clothing store and four or five dachas. Their sons Avram and Lova (Laib) died as soldiers in the Soviet army. Sima remembers getting a letter from Avram, saying that she should claim his salary. Sima wrote back: "I don't need this. You'll need it when you come home after the war." She heard no more from him and then got news that he was fatally wounded near Seltso village. Laib was shot as an undercover agent after parachuting into Latvia behind the lines. A Latvian woman reported seeing a piece of his buried parachute, which led to his capture and execution.

Chaya's oldest son, Aaron, survived the Riga ghetto but lost his wife and son there. He married Sima after the war and they emigrated to Israel in 1972, taking Sima's son Michael. Sima remembers that after she returned to Riga from the U.S.S.R. at the end of the war, with her children and her sister Sonia, she met Aaron at a friend's house. He had survived the Riga ghetto and after explaining that he had nowhere to go, started to cry. Sima told him, "Don't cry. You come home with me. When you get a job, give me your word you won't take another room. You stay in my living room." A few days later they took a walk to a nearby church to listen to the music. The next day, as Aaron was going to register for his ID document, he asked her, "Did you like our walk and music yesterday?" Sima answered, "Yes, I was happy." "So be happy all the rest of your life with me, you and your children." When Sima added, "Maybe we'll have more children," he answered, "No, not more children." Aaron died in Israel in 1974.

Sima's daughter Bella married in Riga and she and her husband and son emigrated to the States in 1980, preceded by her brother Michael. Sima followed in 1987 and all are now U.S. citizens living on the West Coast. Grandma's youngest brother Samuel had moved to St. Petersburg (Leningrad) around 1905 and established his family there. His granddaughter Mira still lives there, as does her son David. When Grandma visited Samuel in Leningrad during her 1934 trip, the Stalinist system was heavily in place but she wrote nothing in her journal about the political climate. She took a lot of positive-sounding, tourist notes—statistics about the number of people and working conditions in the factories, the health care and child care systems—and was enthusiastic about the art museums and historical spots. She also mentioned having dinner with an Aunt Sonia there, but no one in the family can presently identify who that would have been. Samuel, he was put under house arrest for two years afterwards. No one ever told Grandma.

Besides family now living in the States, there were two other branches established outside of Europe—in Canada and in South Africa. The children of Grandma's paternal uncle, Israel/Laib, moved to Canada and established themselves mainly in Montreal, with some members living in the U.S. Grandma's niece, Leah, Hendel's daughter, emigrated to South Africa before World War II and established a family in Cape Town. One of Leah's granddaughters now lives in Ohio with her husband. There is even a connection between the Canadian and South African branches: Israel/Laib's daughter Chia married her tutor and emigrated to Natal, South Africa, perhaps in the same period as her cousin Hendel's daughter Leah went there.

Grandma wrote that Samuel appeared very thin and ill. Sima remembers that when Grandma returned to Riga from Leningrad, she said to her family, "All the old buildings and people there are crying. They're all crying. I'm happy to be back in Latvia." Sima also reported to the family, years later, that because of Grandma's visit to Samuel, he was put under house arrest for two years afterwards. No one ever told Grandma.

Besides family now living in the States, there were two other branches established outside of Europe—in Canada and in South Africa. The children of Grandma’s paternal uncle, Israel/Laib, moved to Canada and established themselves mainly in Montreal, with some members living in the U.S. Grandma’s niece, Leah, Hendel’s daughter, emigrated to South Africa before World War II and established a family in Cape Town. One of Leah’s granddaughters now lives in Ohio with her husband. There is even a connection between the Canadian and South African branches: Israel/Laib’s daughter Chia married her tutor and emigrated to Natal, South Africa, perhaps in the same period as her cousin Hendel’s daughter Leah went there.

To reach the author of any family article contact Esther or Dave at their email address below.