Enter Text

The Father of Polish Photography – The Family of Wilhelm Russ

In the nineteenth century, many families moved to the Drohobycz-Boryław region to work in the burgeoning wax and oil industry. Thus, in the birth, marriage, and death records, we see many new family names that did not appear in the towns before 1854. The earliest record for the Russ family is a birth in 1869, but marriage records indicate Russ births n the region three to four years prior to that. . See also The Family of Dawid Russ.

Wilhelm Russ (1873-1934), called the father of Polish photography, was the owner of photography shops in Drohobycz, Boryslaw and Truskawiec. Many of the portraits that survive from before WW1 came from his studios. Wilhelm (Mechel Wolf), was born in 1873 in Drohobycz to Hersch Russ (b. 1840) and Rachela Rothenberg. The records indicate he had two older sisters, Malka (b.1865) and Kreindel (b. 1869).

Wilhelm Russ, his wife Chane, and their two sons,

Maksymilian and Gustaw, 1919.

Wilhelm, Maksymilian, and Gustaw in Borysław.

Wilhelm married Chane (Anna) Fleisher of Boryslaw. They had two sons: Maksymilian, born in Borysław in April 1912, and Gustaw, born in Vienna, December, 1914.

Like many Galician families, Wilhelm and his wife fled the Russian invasion of Galicia during the First World War to Vienna. Once his family was settled, he joined the war and documented its terrors and destruction in photographs. Subsequently he became known as a practitioner and researcher in the field of microphotography.

.Wilhelm Russ (1873-1934)

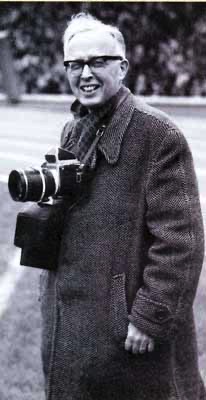

Gustaw Russ (1914-1992)

Gustaw Russ with his daughter Anna

© Valerie Schatzker 2016

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If you feel there is a benefit to you in accessing this site, your JewishGenerosity is appreciated. http://www.jewishgen.org/JewishGen-erosity.

This page was compied by Valerie Schatzker with extensive help from David Scriven.

Anna Russ (1887-1943)

Although it was compulsory for Poles who had been transferred to remain in the western territories, Gustaw was allowed to leave Kłodzko in 1951. He moved to Jasło, a city not yet cleared of the debris of war. Using the equipment from the photographic plant in Boryslaw, he established "Foto-Pam" in one of the surviving buildings. Production technology required proper training of staff. Initially, eight people worked at the plant, but over time, the number of employees increased to several dozen. Gustaw developed the technology of photo-publishing plants. They were established in several cities, such as Wrocław and Warsaw. Several dozens of the negatives his photographs of south and eastern Poland have survived.

From his fourteenth birthday, Wilhelm's son Gustaw helped his father in the photographic studio. Later, Gustaw opened his own photographic studios. He took photos of countryside vistas, professional people, and the rapidly developing petroleum industry.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Gustaw occupied himself with colour photography for advertising in journals dealing with business outside of the country. A traumatic accident in 1977 forced him to go into early retirement. He changed the nature of his activities; he began to write and became a photojournalist. He went where young reporters would not go. He considered cemeteries as neglected museums of masterpieces of known artists and began to document them. He did not live to finish his task but died unexpectedly on January 23, 1992. He received the Cavalry Cross of the Rebirth of Poland and many other distinctions and awards.

It appears that Gustaw's brother Maksymilian Russ fled east in 1941. He and many others from the Borysław area ended up in Alma-Ata, the capital of Kazakhstan, where they worked in factories that had been moved from areas threatened by the war. After the war, Maksymilian, under the name Milek, emigrated to Israel, where he and a friend formed the “Do not forget Boryslaw” committee. In 1948, on an excursion to Nablus, he was killed by an Arab.

After the Second World War, Poles who had lived in the areas that were now part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic were transferred to the areas of Poland that had been taken from Germany. Gustaw left Boryslaw in 1946, but he managed to take some of his equipment from his

house and his photography plant. After a seven-week trip, the transport stopped in Kłodzko in far-west Poland. It was supposed to be a temporary stay, but it lasted five years. Gustaw set up a photographic studio there where he made colourful slides of natural scenes and began to publish postcards. Eventually, the studio was converted into a photographic co-operative. In 1950, he organized a state-owned postcard production plant under name "Foto-Pam”

When the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Gustaw Russ joined the army and was assigned to the 38th division of the Lwów Rifle Infantry, part of the 24th division, where he worked as a paramedic. The 24th division formed lines near Tarnow after which it steadily retreated as far back as Mościska, suffering staggering losses. It was disbanded in mid- September. It is not clear what happened to Gustaw, although some sources say that he was held temporarily by the Germans, but then released. He returned to Drohobycz, which was then occupied by the Soviets and seems to have worked as a reporter and as the editor of the daily Czerwony Naftowiec, as well as being active in microphotography. After the Germans invaded in July 1941, he and his mother worked as slave labourers. The records indicate that Gustaw worked in the geological division in Karpathen Oel, the petroleum company formed by the Germans. Gustaw survived, probably protected by Berthold Beitz, the head of the company who tried to save many of his Jewish workers, but his mother perished in 1943. In November 1944, a daughter Anna was born to Gustaw and his wife, whose name is unknown.