Enter Text

Mordecai Markel's Remarkable Story of Survival - The Markel and Seeman Families

My name is Marcus Markel. I was born in October 14, 1924 in Boryłsaw near Lwów, an area that was then part of Poland. Since 1948, I have lived in Haifa, Israel. I would like to relate everything I know about the history of the Markel-Bartel family. From my childhood, my grandmother and father told stories about our family, and I will endeavor to reconstruct them far as my memory allows.

My Fathers Paternal Family: The Bartels

The stories go back to 1820, the year in which my great grandfather, Solomon Bartel, was born in the village of Lutowiska, near the city of Sambor in the southeast region of Poland. This was the time after the Napoleonic wars that raged at that time in half of the countries of Europe. He married in 1850 (I do not remember the name of his wife) and lived in Lutowiska where he raised his family and ran a farm.

Solomon’s firstborn son, Shamay Bartel, born in 1860 continued the family dynasty in the same village. Shamay Bartel was my grandfather and the grandfather of my cousin Sidney Prince, who lives in the U.S.A.

Shamay Bartel married Sara Hinde Markel in the year 1877. His wife's family had settled in Lutowiska as well. At this time the part of Poland called East Galicia was part of Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruled then by the Emperor Franz Josef, whose policies towards the Jews were tolerant. My grandfather’s wedding was arranged according to Jewish law with kiddush said by a rabbi who signed and witnessed the marriage certificate.

Mordecai Markel

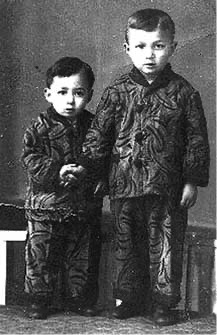

Three of Shamay Bartel's Children

Mordecai’s father, Solomon, his aunt, Molly and uncle Yehezkel

The couple had three boys and four girls. The boys were: Solomon (b. 1899), named after his Bartel grandfather, Aaron after his Markel grandfather, and Yehezkel. The girls were: Molly (Malcia in Polish), Matilda, Miriam, and Frida. Malcia (Molly), the first-born daughter, left Poland after the First World War and married Marcus Prince, an American Jew of Polish origin. They lived in Brooklyn, New York where Marcus worked in a factory that made men's hats. They had two sons, Sidney and Martin, and adopted a little girl.

In 1930, Matilda, the second daughter, married a farmer from the village of Olszanik, near Sambor. I cannot remember her husband’s family name. They had three sons and three daughters. Their firstborn son's name was Wowa. They worked the land in the village and had fields, cattle, horses, and poultry. I had a close relationship with this family. From the time I was five years old my parents used to send me to their home for the holidays, often for an entire month. I liked being there for I could ride horses and drink milk right from the cow. As well, there was fresh farmer's produce, vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, cucumbers, and also fruit: apples, pears, and plums. The produce was brought in horse-drawn wagons to our town of Borysław, where it was sold to merchants. Father, who was a shopkeeper, used to buy it for his grocery. During the war, my aunt Matilda, her husband, and her children, were sent to Belżec where they died.

My father Solomon Bartel was named for his grandfather according to the custom of that time to remember the previous generation and honor it.

In 1922, he married my mother Lea Seeman. They moved to Borysław where I was born in 1924. I was named Marcus after my mother's father. When my paternal grandfather, Shamay, died in 1939, my younger brother was named Shamay after him. There was a problem regarding the family name. My father’s last name was Bartel, but because my grandfather and grandmother were married in a Jewish ceremony and not in a civil one, the marriage was considered illegal. Therefore their children were registered as Markel, the family name of the mother, and not as Bartel, the name of the father. To avoid confusion, my father decided that he would change his last name to Markel in order to ensure that all the family members would have the same name.

In 1940, when the younger daughter, Miriam married Leon Shorr in Borysław, I was a young boy of sixteen. Her husband was a senior worker in the oil refinery where he earned a good salary. In 1941, they had their firstborn daughter, just when the war between the U.S.S.R. and Germany started. I liked Miriam and her family very much. They lived on our street, Lukasiewicza Street, in Borysław, just in front of the police headquarters. They were well off; they owned two houses which they rented and also had a fine private apartment. Near the end of 1942, Miriam was sent with her husband and their baby daughter from Borysław to Belżec.

In 1921, Frida married a farmer whose name was Jagel. They were not as prosperous. They worked very hard on their farm where they had horses, poultry, and dogs. They had two sons, one of whom enlisted in the Soviet army in 1938. One of my Aunt Frida’s sons fought with the Soviet armies during the war and therefore survived. My aunt, Frida, her husband, and their other son died in Belżec near the end of 1942.

My uncle Aaron Bartel was a farmer who lived in the village of Kobło Stare near Sambor. He married in 1920. Like many other family members, he did well. He owned land and ran a farm on which he raised horses, cattle, and poultry. He also traded in horses and owned warehouses of agricultural implements. I do not recall his wife's name but I do remember that they had two sons and two daughters. I sometimes spent my summer vacations with them when I was a child and enjoyed staying in their lovely house.

All of Aaron Bartel's family, he, his wife, and his children were deported from Kobla to the Sambor ghetto at the beginning of 1942. In November 1942, they were sent together with all the Jews from the ghetto to Belżec, the extermination camp, where they died at the hands of the Nazi murderers.

Yehezkel Bartel, my second uncle, married Hudla Zumer in 1940. When I was sixteen, I was present at their wedding. They did not have children. In October 1942 they too were sent from Borysław, where they had been living, to their deaths in Belżec.

Mordecai’s mother and father.

Solomon Bartel and Leah Seeman

My Father’s Maternal Family: The Markels

My Markel grandmother had two brothers and a sister. Her brothers, who lived in Lwów with their families, emigrated to Israel in 1936, In 1939, a month before the outbreak of the Second World War, they brought their parents from Poland to Israel. Because of this, their parents survived and did not experience the Holocaust. They are buried in Israel.

My grandmother’s sister Rebeka, who married Efroim Wilf from Borysław, had four sons: Moses, Dyonyo, Juda, and Herman. The boys raised families, all of whom were killed in the Holocaust, except for Nosia and Jota, Moses' two daughters and the oldest brother. The others were hidden during the Holocaust by a Polish farmer, a good friend of their father, and were thereby saved. The rest of the Wilf family, Aunt Rebeka, her husband, their four sons with their wives and children, died in the Holocaust. There is not one survivor from this family!

My Markel grandmother died around 1927 according to my parent's testimony, leaving my grandfather, Shamay, with six children (Molly had already traveled to the U.S.A). He then remarried. From this marriage another son was born. Since their marriage was a religious one, not a civil one, the baby was registered in his mother's name, Birnbaum. I do not remember his first name. He owned a candy store in Sambor where he lived with his wife and children, a son Belo and a daughter Hela, whom I knew well. When I was thirteen, I was sent to their house for a vacation from school. We became good friends.

Birnbaum's wife was a midwife, a profession that was considered dignified in that period. They were prosperous. During the Holocaust the family was killed, with the exception of the daughter, who worked as maid for a Polish man. After the war, this daughter married and gave birth to two daughters who came to Israel in 1947. My mother was very friendly with them because they had known each other well before the war.

My Mother's Family: The Grünfeld/Seeman Family

My mother Lea was born in 1902 in the city of Stryj, which is south west of Lwów. Her father was Nahum Grünfeld and her mother Berta Seeman. My grandfather was a religious man who obeyed the commandments. They owned a hotel not far from the Stryj railway station. As a child I visited them frequently and loved them very much. They were wonderful people and it was fun to be with them. My maternal grandfather Nahum Grünfeld married my grandmother Berta Seeman in a traditional Jewish ceremony, not a civil one. Therefore my mother, her sister, and her brother were registered as Seeman.

My grandfather, Nahum Grünfeld, had two brothers and a sister. His brothe, Shmuel, who lived in Drohobycz, was killed with his family. His brother Meir lived in the village of Popiele with his family. There is not a trace of them left. My grandfather's sister Boca, her husband, and their seven children who lived in the city of Truskawiec ner Borysław, were all sent for extermination. My grandfather Nahum died in 1940 before the war with Germany. Thus, only I and my cousin, Sidney were left from this family.

My grandmother, Berta Seeman, had two sisters and two brothers. One brother, Itzik Seeman, lived with his family in the town of Skole south of Stryj. There is not a trace of their family. All of them were killed in the extermination camp Sobibor. The other brother

Mordecai’s mother,

Lea Seeman Markel

Hano, who lived in Lwów, was exterminated with his family. The sister Regina, a pharmacist, lived with her family in Warsaw, She died with all her family in Treblinka. My grandmother's second sister Zila lived in Przemyśl with her husband and their five children. They all were killed in Sobibor. My grandmother Berta was driven in November 1943 to Bronica forest where she was shot with other Jews.

My mother’s sister Miriam was born in 1890 and her brother David in 1898. With the outbreak of the First World War the family moved to Vienna, Austria and stayed there until 1919 when they returned to Stryj. They were well off. My cousin David emigrated to Carlsbad in Czechoslovakia where he married a girl from a wealthy family and opened a clothing store for men, women, and children. He had one son Max. In 1938,, after Czechoslovakia was invaded by the Germans, David and his wife succeeded in escaping in a rented plane to Santiago, Chile. He was able to take a fair amount of cash with him. We kept in touch with him until 1941. David died in Chile in 1946. His son Max married and moved to Rio de-Janerio, Brazil, from where his wife came, and worked in the shoe business. His lost his only daughter and his mother to cancer in the same year. He still lives in Brazil.

After returning from Vienna at the end of the First World War, my mother's sister Miriam married. Her husband was a bookkeeper. They had a son, Marcus and a girl, Rosa. Because they lived in Borysław I knew them well. In 1941, after the German invasion, Miriam and her husband were sent to Bronica forest where all of them were shot.

The daughter Rosa was saved by hiding in the office where she worked. Later she was in a concentration camp and in April, 1944 was sent with the other camp residents to Auschwitz. Because she was beautiful, she was not sent straight to the incinerators. She worked as a clerk because of her considerable knowledge of German and English but became ill with tuberculosis and was put into a temporary hospital where she waited to be sent to the incinerators. Fortunately for her, Auschwitz was liberated by the Russian army in January, 1945 and her life was saved. My mother's brother David made contact with the International Red Cross. She was found, ill and in bad condition. She was removed to a health resort in Luzern in Switzerland where she spent two years. After she regained her strength, she was given permission to travel to South America. In Buenos Aires, Argentina she met Max Klein, a Jewish fellow of Austrian origin. They had two sons, Max and George. They visited our family in Israel. After her husband’s death in the 1980’s, she and her two sons continued to live in Buenos Aires, Argentina

My mother Lea Markel managed to survive Auschwitz. She died in Haifa in 1992 at the age of 90. She had grandchildren and great grandchildren and lived her last years in a good way.

Life in Borysław before the War

Before the war, my family lived in Borysław. My parents owned a grocery store that sold fruit and vegetables. They also owned houses and apartments that they rented. With property and enough money to live, my family was considered middle class.

Borysław, south west of Lwów, was a unique city in interwar Poland. It was a centre of oil production and there were about 2,000 oil wells. Poland produced enough oil for its national requirements. The oil industry provided employment for almost all the citizens of Borysław. Of the 50,000 inhabitants, 15,000 were Jews, 15,000 Poles, the rest Ukrainians and others such as Czechs or Germans. Eighty-five percent of retail and artisanal businesses were in Jewish hands. Ninety percent of the tailors, shoemakers, and booksellers were Jewish. On Saturday all the Jewish stores were closed.

In addition to oil fields there were mines worked primarily by Poles and Ukrainians. The miner’s salaries were good but the work was physically difficult.

Economic conditions for the Jews were relatively good. Some of the oil wells were owned by local and European Jews and American Jews through partnerships. The Jewish community included all the normal institutions of a town of this size. Theatre groups would come to perform in Yiddish.

Mordecai and his brother Shamay

1939-1941: The Soviet Occupation

Not long after the outbreak of World War II, on September I, 1939 the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement between Germany and the U.S.S.R. was signed. Galicia was divided in two parts, the western side falling under the German occupation and the eastern part under the U.S.S.R.

In 1939 Borysław was first captured by the German army but on Yom Kippur, the German army left and the Soviet army entered the town. The Jews welcomed the Soviet army with red flags, as did the local workers. Only the local Ukrainians were disappointed for they had hoped that the Germans would help them create a free Ukraine in this area.

Under the Communist regime, all the stores were nationalized and reopened as government or cooperative stores. Schools were under new management, open to all without tuition. Most synagogues were closed since few came to pray in them. Life as a whole was tolerable. Whoever worked could live well..

Mordecai Markel and his 11th grade high school class in 1940.

In the background is the Borysław high school. 1st row right to left: Voytek Perchinsky, Abraham Kehl (died in the Holocaust), Joseph Liebermann (died in the Holocaust), Rawcho and another Ukrainian students. 2nd row right to left: Ivan Pilcho, Volodya Mazur, Mina Binner (survived, lives in Israel), Minia Löw (survived, lives in Israel), Dina Weissber (survived, lives in U.S.A.), the teacher, Ivantziw, Michael Dolim, Stepan Bilim, Segal (died in the Holocaust), Mordecai Markel. Above Mordecai is a student with the name of Mazur.

It was a bit easier for Jews now, since officially no one was allowed to bother them. Life for the local Jewish youth was particularly good. However, the area, now officially annexed to the Ukraine, came under Soviet law. Therefore many young men were drafted into the Red army. One of my Aunt Frida’s sons was recruited into the Red Army in 1939 when he was twenty-one.

Since our family was considered well off in the period between 1939 and 1941, we lived in fear of being sent to Siberia by the Russians. My father tried to be a model worker to avoid this and fortunately we were not sent away. Our life remained relatively normal.

In 1940, we received a postcard from Aunt Molly in Brooklyn asking about our family and everyone’s health. Through the international Red Cross, my father answered her informing her that everything was fine.

This photo of Mordecai’s high school class was taken on June 21, 1941, one day before the German invasion. Mordecai is in the middle row on the far left. Next to him is Mina Binner, a Mazur, Minia Löw, Dina Weissber, Perchinsky, Rawcho and Zulin. The front row left to right: Abraham Kehl, Bilin and a Jewish boy who was killed in the war.

The German Invasion and Life under the Nazi Occupation

On June 22 Germany declared war on the USSR. The Germans now invaded all of the area of Eastern Galicia where the Bartel and Markel families lived. I remember well the day the Soviet forces withdrew from Borysław. We lived at 54 Lukasiewicza Street, not far from a wax factory. The Soviet army destroyed this factory. In the process, half of the houses on that street burned down, including our house. The German army entered the city the next day and gave a group of Ukrainians free reign for twenty-four hours to organize a pogrom against the Jewish residents. Many Ukrainians from nearby villages came with axes and sticks to beat and rob the Jews. Some of the peasants even took apart the tin roofs of Jewish homes and loaded them on their wagons to take home.One hundred and eighty-two Jews were killed in this pogrom. Most of the rest hid in their cellars or away from their homes. Anyone that was caught by the mob was killed

After the fire, we were without shelter. A Gentile friend of my father came to warn him of the pending pogrom and helped us find shelter in an abandoned shack near our former house. We stayed there all day and all night.

The next day, a friend of the family brought us to a house abandoned by a Russian family that had left with the Soviet authorities. It was a two-bedroom apartment, completely furnished. We had everything that was needed to run a household.

The next day, strange rules were imposed on Borysław’s Jews. We were not allowed to leave town. All persons above the age of thirteen had to report for public work, and also had to wear armband identifying him or her as Jewish. A Judenrat or Jewish council was selected by the authorities to represent German demands on the community. The Judenrat was responsible for creating a list of those who had to report for public work daily, without pay of course. In this manner, Jews did all the dirty work, such as cleaning the Soviet apartments that were abandoned to prepare them for the new German officials, road paving, etc.

I was then seventeen and had to report for public work. My task was the collection of weapons abandoned by the Soviet army. The work had to be done without any breaks, without food or pay. Food was hard to find even for those who had money. The stores that passed into Polish and Ukrainian hands refused to serve Jews. Not even staples were available since most went to supply the German army. The citizenry received food through ration cards. Germans and Volksdeutsche (Poles of German extraction) were entitled to more rations than Poles and Ukrainians. Jews got the less expensive products. The Judenrat received permission to open a store for the distribution of bread, flour, and sugar, based on weekly allocations. It happened that my father received a job in this store. For this task he received a half a loaf of bread free of charge, in addition to the two kilograms per week allocated to each Jew. With this additional food we managed to exist somehow.

We would normally return from work at four o’clock in the afternoon. Afterwards my brother and I had to do all manner of housework. We had Polish and Ukrainian friends who respected my father but they were afraid to come to the Jewish quarter. At night, they would sneak to our house bringing vegetables, flour, and potatoes. Of course we paid them. This trade was conducted only between persons who trusted each other. Later we received grain that my brother and I would grind at home. It was hard work that took about four hours. Our hands hurt and as a result, we did not sleep well. My mother and grandmother would mix the flour with potato flour, bake bread and sell eight kilos the next day. This brought a profit of two kilos of bread for our family. This profit was significant.

Because of the unsanitary water conditions, a typhus epidemic spread in town, and many Jews died. They also died of malnutrition as a result of hunger.

In August 1941, the German authorities demanded that Judenrat supply the authorities with furs and leather boots for the German army fighting on the Soviet front. They also demanded that they supply a list of the 5,000 Jews and their addresses and that 5,000 workers be recruited for all sorts of public work. When the German police came to these addresses, they did not find the residents in their homes. The authorities reacted to this defiance with their first Aktion. They went from house to house, loaded the residents unto trucks, and brought them to the railroad station. In this manner they collected thousands of Jews and loaded them into a train. Later we learned that they were shipped to Belżec, a death camp north of Lwów.

The Jewish population decreased from 15,000 in 1939 to 10,000 after this first Aktion. After the Aktion, forced labor was terminated. However every Jew above the age of thirteen was required to register at the Arbeitsamt (labour office) to receive an Arbeitskarte (labour identity card) with his photo on the document.

The Germans began to define an area within the city as the Jewish ghetto. The Judenrat resided in Kosciuszko Street. Originally there was a Talmud Torah school and also a Dom Zydowskl, which was a large hall used for things like meetings and performances. Near this hall was a large yard where the Jews assembled to report to work. However, after deporting 5,000 Jews, the Germans began to demolish the ghetto.

In the middle of Borysław city, the Tyśmienica River flowed. Because the river was very dirty, filled with oil and petroleum, it was possible neither to bathe in it nor drink from it. Above this river was a wide bridge, fifty by fifty metres ,with a paved road that had been built in the 1930's. At this bridge, the main four roads of the town met to form the main intersection. The roads followed the paths of the four winds: north along Drohobycka Street, south along Kosciuszko Street, the main street of Borysław leading to the area of Mrażnica, west along Łukasiewicza Street, and east along Wolanka Street, which led to the spa town of Truskawiec. On these four main streets were the neighborhoods of Derby, Nowy Swiat, and Targowica, the main center of town. All these neighborhoods were filled with Jews many of whom owned all the shops, businesses, and houses in those streets. No wonder the anti-Semitism was so great in this town; the Gentiles hated the Jews and many were glad to help the Germans get rid of them.

The Germans allocated specific neighborhoods for Jews only, especially the main part of Łukasiewicza Street and the main bridge, including all of the neighborhood of Derby. All Jews were compelled to leave their homes and move to the ghetto. The ghetto was not surrounded by walls or wire fence. The area was open from all the sides so that walking in and out was possible but Jews were not allowed to live outside the ghetto. All the Jews who survived the second Aktion began to move to the ghetto. There they lived, two or three families in one flat or, more exactly, one family per room. In a terrible way, conditions improved for the Jews, because the families became smaller after each Aktion and as the Germans exterminated members of these families, fewer were left and therefore there were fewer mouths to feed. Other people simply died from hunger or typhus and again there were fewer mouths to feed. After this period, Jews who were sent to work did receive wages, though smaller than those received by Gentiles for comparable work. In addition, these workers received a weekly allocation of food such as bread, flour and sugar.

The Jews of Borysław no longer had radios or newspapers. They had little energy after a day’s work. Almost nightly, the Germans would invade homes to rob the residents. The situation was intolerable. Each person, however, thought only about his own survival and did not care about the fate of others.

I was assigned to a group of four Jews who were knowledgeable about oil-pumping machinery. I remember David and Berl but have forgotten their last names. Their family had a large warehouse of old iron and were among the town’s richest Jews.

Together we left at five in the morning to work. Every day we went to a different oil well where we collected iron wires. These were sent to a town called Kuty where they were used to guide ferries for the transfer of goods over the Dniester river. With this work we survived the winter of ‘41 and ‘42. Most of the oil workers were Gentiles. They had pity on me because I was young and handsome and worked hard. These workers were professionals. They received good salaries, and lived in good apartments formerly occupied by Jews. For me, as with most Jews, the main issue was food. Hence, the extra rations I received from my co-workers helped me survive.

In the ghetto apartment where we lived with the Weisbard family, we had one room; the Weisbard family occupied the other room. We hoped to survive this difficult period. Each one of us believed that G-d would not abandon us, that we would survive. The men put on tfilin daily, and prayed to G-d. We had great faith that we would survive. At this time Borysław had 10,000 Jews. We went to work every day. Each of us sought local work in order not to be sent out of town. At that time we believed that those loaded onto trains were sent to work in Germany or to another location.

Several Gentile contractors worked at locating new oil wells. The work required the leveling of the hilly land around Borysław. These contractors were glad to have Jewish workers for digging wells and difficult physical labor. Jews, who in the past were always traders, were not used with physical work. They did it because there was no choice. Each Jew had to register at the Arbeitsamt to receive a document showing that he had registered for work.

I was sent to work paving the streets of Borysław. Since the main street was damaged after Soviet tanks had driven through it, the municipality had to improve this street. Trucks brought large stones. which were loaded and unloaded by Jews. A group of workers broke these stones into smaller pieces with a hammer tied to a one-metre long pole. This was back-breaking work for young Jews who, until now, studied in the Yeshivas and had never worked like this before. Because I was a young and strong lad, the work did not discourage me. On the contrary, I developed my muscles and worked hard for the small weekly salary I received. Another group loaded the smaller stones into a wheelbarrow and brought them to the street. A group of professional Gentile workers laid these stones. The spaces were filled with sand and everything was packed into the foundation with a steamroller. This is how streets were built in 1942.

While other Jewish workers would be hit with rifle buts and sticks by their overseers, I did my work diligently and my supervisors were satisfied with my performance. After one week they removed me from this task and as a reward, assigned me to pour sand between the stones, an easier job. I was the only Jew among the Gentiles doing this work. One day, when my co-workers were dressed in heavy clothing, I was sweating. I took off my coat, rolled up my sleeves, and continued to work. Our street work was complete. We were located at the end of this street near the German oil company's headquarters..

In those days there were no private cars in Borysław. I remember only one private car, a Skoda automobile, owned by a rich Jew named Hecker. In 1939, the Soviets confiscated the car and sent the family to Siberia. Two buses served to transport people to Drohobycz, thirteen kilometers from Borysław. All the top managers traveled in the city in buggies pulled by horses. It was on that winter day, as I was working with rolled up sleeves, that such a manager passed our group and asked that I come to his carriage. He asked for my name; he told me that he was the top executive of the Beskiden firm. He told me that he wanted me to work for his company and to come to his office tomorrow to receive a work detail.

I did not think much about it. I decided that working at his company would be easier than my present assignment. However I told the man that I was not allowed to leave my job without permission. His answer was: “My name is Siegismund; I am an important personage in this town. Tell them my name, and they will all help you. You will forget about working for the city when you transfer to work for me.” The Gentiles who overheard the conversation wished me success. I must say that they all were happy for me. The next day, the work supervisor knew about this and approved the transfer. The guard at the Beskiden Company knew that a Jewish worker would be arriving. A clerk ushered me into Mr. Sigismund’s beautiful office. There I was. He turned me over to his secretary who was to deal with the details

First, she stamped my ID with the Beskiden stamp to indicate that I was one of its employees. This was a precedent; I was the first Jew to be employed there. She also placed a round stamp on my armband. Also, I receive a printed sheet with the company letterhead and her name on it and a permit to allow me to move freely day and night through the city. I must emphasize that the city had a nightly curfew for all its citizens, called Sperstunden in German. This permission was a big deal in those days. The secretary told me to report to my new work place at the machinery warehouse on the following day on Sh… Street, and report to Mr. Schtepnick (hereafter shortened to S.)

When I was about to leave, Mr. Siegismund called me to his office and told me that I should know that my supervisor was an important German, an ex-officer who had been wounded in his head at the Russian front, then discharged. He was working now as the warehouse supervisor. He cautioned me that Mr. S. was a difficult, exacting person who demanded good work. He added that Mr. S. could not be paid-off or argued with. He was like a German officer who expected everyone to obey orders and work diligently. Cooperating would enable me to live in peace, perhaps stay alive. With that our conversation ended.

Because there was no public transportation in the city in those days, we were all used to walking to every destination. As a student I was accustomed to walk several kilometres to school in any kind of weather. On this day, I arrived home at noon. I noticed nervousness among the pedestrians. No one spoke. All were running to and fro. My father, who worked in the ghetto distribution centre, was at home, telling us that something would likely to happen in town, possibly a third Aktion. Information had leaked that members of the Judenrat had worked all night composing lists demanded by the German for sending these persons to a work place out-of-town.

It was my father’s opinion that the Germans would take only adults. My father was then forty-four and my mother forty, an age that was then considered old. He thought that lads around seventeen to nineteen would be left in the city to work in the oil fields, since this work was essential to the German war effort. My parents decide to leave the house and hide in the ghetto distribution center. Four families hid there. For some reason, my parents did not take my grandmother with them.Thus my brother, grandmother and I remained in the apartment.

The evening meal in those days was porridge made of black flour. Mother would boil water in a pot and pour flour into the boiling water to make porridge without fat, butter or oil. Each of us received one plateful of this concoction. For us it was a treat, since hundreds of Jews did not have this food and were always hungry.

Our neighbors, the Weisbards, went to hide with a Gentile family, where Mr. Weisbard had worked as a women’s tailor for two weeks.

I remember that it was a Tuesday. I got up early and prayed with my tfilin as I did daily. I had a strong belief that G-d was with me and that nothing bad would happen to me. I stood at the window saying my shmoneh esreh prayer. Suddenly I heard terrible shouts in German at the nearby orphanage, “Rauss, rauss!” and the heart-rending cries of children. I looked out and saw the Germans and the Ukrainian police dragging orphans from the orphanage on the other side of the street and throwing them into trucks as if they were bags. The children cried and the Germans fired their guns in the air. I went down from the top to the bottom floor to find out what happened but just when I got there a Jewish kapo named Mundek Brunengräber saw me and warned me to run away because the Aktion had started. He knew me because he had been a good neighbor when we lived in the house that had burned.

He said the Germans had lists of people to round up but because he didn't believe they would follow the lists to the letter, he ordered me to get away. I ran back upstairs from where my brother and I saw the whole city wake up. There many German soldiers in green and black uniforms. They were Gestapo and S.S. and also many Ukrainian police. Each group was accompanied by a Jewish kapo who was ordered to follow them. The kapos were a group of Jewish policemen organized by the Germans to keep order. The Judenrat members and the Jewish police tried to carry out the orders given to them because they were afraid for themselves and their families and thought they could somehow protect them this way.

We saw Jews dragged, beaten, and thrown on trucks. Suddenly we saw Rabbi Yankele, that good man, wearing his talith and tfilin dragged to the truck. They hit him with their guns, spit on him, and pulled his beard. He was thrown on the truck as if he were a piece of wood. I couldn't even cry at that moment. I couldn’t think about anything. I just watched the horror. Even Meier Glanzman, a strong Jewish man, was dragged and thrown to the truck like a log of wood. He was a holy Jew in my eyes because every Passover, my father would bring me to him for a blessing since he was a a child.

Suddenly I saw a group of Germans approaching our large yard, taking out Jews from all the houses around to be put under the guard of the Ukrainian police. Then they started heading for our apartment.

Mr. Nemetz, a tall Austrian, who was commanding the Ukrainian Police came to my apartment, demanding to know where I worked. I showed them my work papers and travel authorization. He then asked about my brother. I answered that he too worked there. Mr. Nemetz slapped me on the shoulder and told the Ukrainian policemen, “ These two lads will stay here”. Then they all left the apartment. I knew that I was saved again. I knew that nothing would happen to me. Nemetz and the police came again to look for my grandmother who was hidden in the other room. They found her but responded to my entreaties to leave her. Later he called me down and told me, “We came back because the Jewish policeman told us that there is another room on your floor in which a family is hiding.” With that, the story ended. Later, the Ukrainian police came for me again because they were unable to fill the quota for the train, but I escaped through the window and my brother escaped from the convoy to the train station.

The next night they repeated the search because the train was not filled, but we were able to escape capture. Later we heard from Mr. Keller that eighty train coaches were filled with between 5,000 to 6,000 Jews. Keller added that Mr. Sigismund came to the train station and from the assembled Jews, selected one hundred lads aged seventeen to nineteen to work in his business. They also said that he went from coach to coach asking for Marcus Markel. He thought that I might be in the train and wanted to save my life.

I would also like to mention Mr. Linhard, and Mr. Reiss, who were befriended by the notorious Nemetz, the Police chief, who did not arrest me during the third Action. Reiss was a learned man who taught German to the Ukrainian police. Nemetz enjoyed talking to Reiss, in German of course. Reiss did not live in the ghetto but rather in the police quarters. In this way he remained alive. Most of the German high officials kept Jews in this way because they needed them, either for conversation or particular work. Each of these Jews who were saved had a German ‘patron’ For some reason that is unknown to me to this day, I also had such luck because of Mr. Siegismund. The reason for his friendship became clear only some time after he hired me as the first Jew to work at the Beskiden Co. Mr. Siegismund had a wife, two daughters, and a son. The son was a member of the Hitler Jugend who had volunteered for the army, asked to serve on the Russian front, and was killed there. I happened to look like his dead son.

After the third Aktion, the ghetto had shrunk and a new Judenrat was appointed by the German authorities. The hundred young Jews who had been selected at the train station for work at Beskiden were assigned to various jobs, as clerks or professionals. About one thousand Jews received the armband stamp “A”, indicating that they were essential workers. The hundred young Jews selected by Mr. Sigismund tried hard to show their gratitude for being saved from transportation by bringing him cloth, leather, and furs, items that had been hidden in the homes of departed Jews. His house was filled with these articles.

I forgot to mention that after the third Aktion, I reported to work at 7:00 AM. Mr. Sigismund was there with his coachman. When he saw me, a smile came over his face. He approached me and asked where I had been during the days of the Aktion. He also asked whether my parents were well.

I must now tell about my new work assignment. It was difficult work but because of it, I and my parents remained alive.

Beskiden hired a few more Jews, who therefore had the “A” stamped on their armband. Other Jews worked for outside contractors involved in the search for new oil wells or their maintenance. I decided that it was necessary to find a hiding place for my parents. Three friends and I had heard of an abandoned beer factory with a large cellar. A shack stood over the opening to the cellar. After work we cleaned up the cellar. It was partly filled with water. We built a platform over the water to make it habitable for our parent. The wood came from the Jewish houses left vacant after the last deportation. Before the war, our Borysław homes did not have running water. Each street had two wells, where we could get water. The toilets were outside. We dug an entrance to the hiding place from a simulated indoor toilet.

After Mr. Siegismund. received the aforementioned presents, he asked me to identify and send him craftsmen to work on the material he received. I identified our neighbor, Mr. Weisbard, as a women’s tailor and three others. These four Jews received the coveted “A” sign while working in the home of Mr. Siegismund. They also received their meals at his home. Both parties were satisfied with this arrangement for food was very important in those days. The Sigismund family was suddenly drowned in wealth after one hundred Jews filled their home with all those goods. The truth is that this saved their lives.

Our work was to place spare parts for machines in a warehouse in a most orderly fashion, typical German order, just like in the army. Every item was numbered. These machine parts were needed for local oil production. In addition to machinery, there were metal pipes of various sizes and length. Machinery arrived well packed in crates. Approximately ten wagons full of spare parts arrived daily in boxcars. The warehouse was full of goods and important items essential to the German war effort.

Mr. Schtepnick had fifty-nine employees, a secretary, and a clerk. He was a little strange. He employed two night guards, from 6:00 PM to 7:00 AM, who had to be awake throughout the night. Two German shepherd dogs assisted them. The dogs were locked up during the days and free to roam he warehouse at night.

There were fifty Ukrainian employees, divided into five groups each with a straw boss. These were young, healthy, strong, young men from neighboring villages who came to town in search of well paying jobs. They worked well and received food packages from their families. We worked on Saturday until twelve noon. These workers returned to their villages that day. Upon their return they brought many tasty foods, including cakes. They often returned with stories regarding the killing of local Jews whose houses, property, and fields were taken from them.

Of the hundred Jews Mr. Siegismund selected to work at Beskiden, four were sent to work with me. We five Jews were expected to do the same amount of work as the team of ten Ukrainians. This is what our crazy supervisor demanded.

I was chosen to head our group. Its task was to load and unload trucks and wagons with all manner of machinery and pipes for the various plants in town in accordance with the delivery requests for that day. There were no forklifts in those days. All had to be done by hand, which required training, experience, and mainly common sense.

In the first months, my supervisor stood near us giving orders. We were not allowed to speak, smoke or eat during work time. Although he yelled his orders, we saw that he was an expert at this work. Although we worked in all kinds of weather, none of us became sick or caught a cold. He directed us for three months, the time, he told us, it takes to learn good work skills and habits. We really learned to work well with him. Each day we received a half hour lunch break. The canteen served a hot soup, vegetables, and a slice of bread. Meat was not served. We Jews were not allowed into the canteen. Another employee brought out pots of food, which we ate outside.

Our supervisor was happy with the Jewish team whose intelligence allowed them to learn how to load and unload in an efficient way. Hence their work stood out. We continued to work in this manner for two years. Mr. Sigismund came to the office from time to time. He would ask me if I was satisfied with my job. I told him "sehr zufrieden," meaning very satisfied. I wanted to stay at this workplace for other reasons that I shall explain later.

Our supervisor asked for two volunteers to care for the dogs during the day. Mr. Weingarten and I volunteered. We fed them and gave them water and straw. The dogs loved us and we loved these clever dogs

During the fourth Aktion, forty Jews were killed and hundreds taken to the train station to be shipped out. My parents hid in the aforementioned cellar. All returned except for my brother Shamay, who had been working for a Polish contractor. The next day my father and I located another Jew who had worked with my brother. He told us that he had hidden at his work place but did not see Shamay that day. We went there and found him dead. We were told that two German policemen on horses chased my brother and shot him. One bullet hit his ear. He was only sixteen. We stood there next to his body, not knowing what to do. After fifteen minutes, my father asked an old goy for wooden slats to lower the body to the nearby road. We transported him from there to the main street. My father cried. An old man with a wagon agreed to take us to the Jewish cemetery with the body. We dug a hole and buried him there. We went home to sit shiva but only in the evening, because I had to work in the daytime.

Mr. Siegismund kept Mr. Weisbard and the other employees in his house during this fourth Aktion.

The Germans had again diminished the ghetto area but we remained in our apartment. The Germans created a work camp at Mrażnica. It took a while to build and organize this camp with a kitchen and infirmary. When it was completed, the Jewish workers at Beskiden moved into this facility.

There were goyim that helped Jews hide, sometimes for money, sometimes without compensation. One such person was Manka, a neighbor of ours, who before the war worked in the home of the Wolff family. When the ghetto was made smaller, she moved into a home previously occupied by Jews and established a bordello in it. She had three prostitutes in her employ. There was brisk demand for their services by German soldiers. I asked her if she would be willing to keep my mother and grandmother in her basement. She agreed to hide them without payment. I remembered that prior to the war when she was often in economic difficulty, my father would give her enough food for months without asking for payment. Manka not only housed the two women, she also fed them. They were hidden there for two months.

The fifth Aktion took one month. The job of catching Jews was given to the Jewish police. They were animals, like the Germans. When they caught Jews in a hiding place they demanded a bribe. Whoever did not have the means was taken to the coliseum, a holding pen for deportees. When a person was let go due to a bribe, they had to find a replacement, a process that took about a month. I remember Valek Eisenstein was one of these. They made a lot of money, would play cards, and drink. One day my grandmother felt ill. Manka came to my place of work to inform me of this problem. In the meantime, my mother and grandmother went out to visit a doctor on their own. Of course, the Jewish police caught them and brought them to the Coliseum cinema. I ran after them and caught up with them before they reached the coliseum. I told the person holding my mother that I would kill him if he did not release my mother. He knew that I was protected by Mr. Sigismund and seeing the fire in my eyes, he released her. I ran with my mother to the warehouse. The guard let my mother and me in when I promised him that she would leave in the morning. I then wanted to leave to see what could be done about my grandmother. Because my mother, forty years old at that time, was afraid to be left alone with the two Gentile guards, I stayed with her. My grandmother was fifty-two. She and the Jews in the Coliseum cinema were later marched to the Drohobycz forests and killed there.

This was the end of the ghetto. Eight hundred men and two hundred women remained in the work camp.

My father still worked at collecting clothing and furniture in the abandoned apartments. Only five workers remained. They received the letter “R” on their armband indicating they were working for the Rüstungsindustrie (armament industry).

I continued to work at the warehouse. On one of his periodic visits, my patron, Siegismund, took me aside for a long talk. He told me that he and his family were being transferred to Lwów, the provincial capital. He had been made director for all of Western Ukraine. He suggested that I join his family in order to stay alive and told me that the Jews of Borysław had no hope survival. I was shocked to hear these words. I was eighteen. I told him that I had parents and felt responsible for them. He tried to persuade me that it was possible only to save me. He offered to adopt me legally so that I could to live peacefully and comfortably. He suggested that I forget my Judaism and all the troubles that this religion meant. I must admit that I felt uneasy but my decision not to abandon my parents was firm. I was young and did not think of my future. Life seemed like an adventure. I felt strongly that the Germans would not catch me. Mr. Siegismund suggested I consult my father. I told him that I could not do this. He gave me his hand. I kissed it with all my heart. Despite his membership in the Nazi party he was a good man. We parted and I never saw him after that. He was replaced by Mr. Beitz.

At the work camp, the routine was to rise at 6:00 AM. From the kitchen we received one hundred and eighty grams of black bread. We were given a black, hot drink that that resembled coffee or tea but had no taste. The Germans also lacked tea or coffee in those days. We also got fifty grams of marmalade. This was our daily diet. In the evening we received a soup, one hundred and eighty grams of bread, and fifty grams of marmalade.

It is clear that one could not hold out on such a diet while working for ten hours. Each of us organized ways of adding to our food ration through our Gentile co-workers or by stealing on the way to and from work. A trade developed in the evening. Apples, eggs, bread, and vegetables were sold in the hallway in the evening after dinner. Potatoes were the item most wanted because the men knew how to cook them. I would bring apples, pears, and cucumbers. I would fill my pockets with these items and sell them by the slice. With the profit I would buy potatoes, cook and eat them. I learned to eat and enjoy potatoes daily.

I organized a hiding place for my mother in the warehouse. I fed her secretly with the water and potatoes that I purchased and cooked in the camp. Next I found a hiding place in the local cinema. It had running water and toilets. Mother was in seventh heaven. The men from the Judenrat, whose task was to empty the houses, would trade a blanket for a loaf of bread, china for eggs. In this manner, the five Jews of the Judenrat managed well. They brought the food they traded to the cinema.

One Friday, my supervisor told me in secret that another Aktion was scheduled. I was not concerned about my fate, but passed the information to my parents in the hiding place in the cinema. I suggested that the men not report to work the next day. On Saturday, my workday ended at noon. The men, including my father did not listen to my suggestion and were taken to the Ukrainian police station

I had two friends among the Ukrainian police who had been in my class in the gymnasium. When I told one of them the story of my father’s arrest, he took me to the basement of the police building where my second friend in the police force stood guard. The latter acknowledged speaking with my father but said he could do nothing. At the end of his shift he was obligated to count the 183 Jews and account for each one. He did agree to take my father out of the stinking room to let him breath fresh air. My father took out an Omega pocket watch, and gave it to the guard Byslushin. He agreed to let my father stay in the corridor until the shift changed. I decided that only Nemetz, the Police Chief could help me free my father. With my policeman friend, Helbake, the third of my old schoolmates in the police force, I went to the top floor but Nemetz was not in his office. I next went to his residence, where he lived with a Jewish family called Greenspan. At first Nemetz laughed at me; he offered me a glass of vodka to drink to his health. When I refused to accept his offer until my father was released, Nemetz became angry. He left to fetch my father from the police building next door. He then offered a drink to my father and insisted that all three of us drink l’chaim. He then slapped my father on the shoulder and told both of us to disappear. Father did not know what hit him. The 182 Jews were killed on Sunday and their clothes were distributed to us in the work camp.

Weingarten, who worked with M. taking care of the dogs during the day, proposed to M. a new hiding place under the tool shed inside the warehouse. Thus Weingarten’s wife saved herself from the trip to the killing fields.

Later, when another man left the work camp, M. was able to get my father registered with an “R” (essential worker sign) and get him a job at Beskiden as a coachman transferring spare parts wherever they were needed. This enabled my father to trade with the goyim he knew. He would buy apples and pears that were then plentiful and bring them to the work camp where I would sell them. Our economic situation was good. My father and I slept together on adjacent beds. Every evening I would cook potatoes and we would eat them together. Meanwhile Mrs. Weingarten and my mother were hiding in the bunker under the tool shed.

The Germans knew that in order for us to continue to work in winter of 1943, we in the work camp needed warm clothing, so they brought the clothing of the Jews that were periodically caught and killed. We looked in this clothing and sometimes found dollars and gold hidden in them and also identity cards. With these we were able to purchase additional food.

In the summer of 1943, the two women who were hiding in the bunker could not stand the confinement anymore. I brought them to the work camp that was guarded routinely by Ukrainian police. They were bribed by the Jewish police as were the two SS commanders.

One day Nemetz came for a visit. I was in the hall selling apples. While other Jews ran away I stayed put. Nemetz recognized me and asked me the price of the apples. I offered him a low price and he bought some.

Later there was a need to build another bunker, this time in the house of the new director of Beskiden, Bombowitz. This man had been transferred at the end of January 1944, when the Russian were only several hundred kilometers from the town. At this time, the local goyim started to treat us better. They helped us with food and talked to us.

Our supervisor, Mr. S. also relaxed his rules. He let us rest occasionally and was on better terms with us. In March 1944, the Soviets were in Tarnopol. We expected them to reach us less that one week.

One day, the work camp commander told us to just leave. The work had ended. My father and I went to my mother’s hiding place in the Bombowitz villa. The Red army had stopped at Tarnopol. Now, the workers returned to the work camp. One day, the German police surrounded the work camp and sent all the inmates to Plazów near Kraków.

In May 1944, we were careless and sat outside our bunker in the garden. when I went into town to buy food as I did regularly. The neighbors’ children discovered the bunker’s entrance and told their parents about it. We were brought to the work camp and on July 22, 1944, all of us were driven to the railway station to be loaded on a train for Auschwitz. We left on July 23 and arrived in Rychcice near Drohobycz, on July 24 after many starts and stops. In fact, we travelled only eighteen kilometers throughout the night. In the morning, the German guards opened the wagons and let us out to use the restrooms. My parents woke me up and begged me to leave and not come back. I entered the budka, the outside toilet. The Germans guarded the front. With my foot I pushed out the old wooden slats, and escaped from the back.

However, my parents went on in the train to Auschwitz with three hundred other Jews. The train lines going to the west had already been bombed by the Russians. The train had to be rerouted via Slovakia. My parents arrived in Auschwitz on August 10, 1944. In Auschwitz, the men were immediately separated from the women. My mother went to the Birkenau camp for hard labor until her release in January, 1945. My father was sent from Auschwitz to Austria to Mauthausen, an extermination camp, and from there to a very difficult labour camp, Gusen II. In this camp, all the Jews died from hard labor. At Passover in 1945, my father collapsed during the morning line- up and did not rise again. He was forty-four at the time of his death and his burial place is unknown.

After escaping from the outhouse, I walked quickly in the opposite direction from the train toward the train station. I found out that the locals had been waiting for trains for two days because there were no locomotives. The Germans had taken all of them. I went toward Drohobycz, walked for an hour, and reached the town. I stopped at a well to drink and continued my walk until I reached a kiosk where they were selling cherries. A German soldier went in, apparently to buy some, leaving his bicycle parked outside. I took the bike and peddled rapidly towards Borysław. On the way I saw a convoy of wagons coming from the opposite direction. When they came nearer, I recognized them as the local policemen with Nemetz in the lead wagon. Nemetz recognized me and wished me well. I also shook the hands of my two policemen friends from school. They were headed to Sambor.

At Hubice, I drove over some glass and got a flat tire so I walked the rest of the way to the center of Borysław. On the bridge I met a prostitute who offered to take me to her place; it was the bordello of Manka, the Madam, our former neighbor. Many German soldiers stood in front of the house waiting their turn to be serviced by two prostitutes. When I came in, Manka asked no questions. She gave me the job of collecting the two marks from each soldier when his turn came. I dedicated myself to my new assignment. This process continued until 1:00 AM when the last German soldier left. Afterwards Manka prepared a good meal with wine for her workers and me. She told me that the police and SS had left. There were only German soldiers passing through town in retreat from the Red Army. That night, I slept well in a normal bed.

Since the Russian did not come the next day or the day after, business continued. The prostitutes would bring the soldiers from the bridge and I would collect the fees. Towards the end of July, there was no more food in the local market. We were flooded with marks and zlotys (Polish currency) but could not buy anything. The prostitutes decided to go to the villages to buy food. The villagers told them that they would not take money. They need matches. I went to a warehouse where the Germans had stored matches and took a large crate. We divided the matches into shopping baskets and took these to the farmers to trade for butter, cucumbers, and bread. One farmer treated us to an evening meal.

Liberation

On August 6, the Red army entered Borysław. I was free, but had to live with the thought that I had lost my parents only two weeks prior to liberation.

About three hundred Jews survived in Borysław. They had been hidden in all kinds of places. The Russian announced that all men over twenty had to register for the draft. I was classified as type three, not fit for the army, but suitable for work. There was nothing for me to do in Borysław. I thought that it was possible that my parents had survived in Auschwitz and that I ought to move westward as the areas became liberated by the Red Army.

We heard that the Red Army had liberated Lublin. In Borysław, I had come to know a Lublin Jew named Zalenka. He had masqueraded successfully as a Pole during the war because no one knew him. Now he wanted to go back. Both of us had money because a friend knew of a hidden treasure that I helped dig up. My share was 5,000 zlotys. Żelonka and I hitched a ride to Drohobycz with Russian truck drivers who took civilians for one ruble or one zloty. There we bought food and hitchhiked to Lwów for five zlotys. From there we left by military train to Lublin. The authorities in Przemyśl did not check the military train.

When we reached the railway station soldiers stopped us and checked our papers. Since I had a temporary dismissal letter from the army and Żelonka was over sixty years old, we were released. We went down towards the railway lines and saw a convoy of train cars. We asked the soldiers for permission to join them on the train,

Mordecai Markel (right) in 1945

with Franek Pollak, a survivor from Kolomea. The photo was taken in Poland.

received it, and boarded one of the cars. On the open car there were two big guns and thirty Russian soldiers. Two Jews were among them; they told us they were heading to the west, to Berlin.

Late at night the convoy started moving so we travelled this way all through the night. We talked with the soldiers and told them what happened to us. We told them we want to get to Lublin. In the early morning, the train stopped in the Przemyśl station that was then on the border between Russia and Poland. Usually they were checking everyone who crossed the border but since we were traveling with an army convoy we were not checked at all. After waiting two hours, the train started moving again.

In the evening we came to the city of Rzeszów in Poland. The Russians told us we had to change trains for one that would go to Lublin, because they were going another direction. They gave us four loafs of bread and some tinned food. We thanked them and disembarked at the station. We boarded a passenger train for Lublin. It was empty and since we wanted to get to Lublin and had been told that the train was going there, we stayed.

We slept for a very long time since we were dead tired. n the morning when we awoke, we found that the train had stopped in a field. Apparently a bridge ahead had been demolished by bombing so the train could not continue to Lublin. We found out that we were just three kilometers from the city and decided to continue on foot. We bathed in the river, ate something, and started walking. It took us an hour to get to Lublin. When we arrived, we saw many Russian and Polish soldiers ther; it was very noisy.

In Lublin, I quickly realized that many of the Polish army officers were Jewish. In the USSR, they had changed their names to Polish ones. With these new names, they were accepted in the Polish army that had been organized in the USSR.

As we were walking in the street of Lublin, a person approached me and said “Amkha”. At first I did not understand but after a moment I realized that he meant “our people”. He told us about a Jewish committee on L… street where we could get help. There we received coupons for food and lodging in the Peretz house. I noticed that people were putting up signs with their names and towns of origin. I did the same. We had a hot meal and went to the Peretz house to sleep. At midnight I heard someone shout, “Markel from Borysław.” When I woke up I saw a Polish soldier named Schiff in front of me. He asked me what I knew about his wife. I told him that I remembered her that she was alive and in Borysław. He suggested that I leave the Peretz house and visit a Mr Tepper from Borysław, now a Polish officer responsible for the Soldiers Home in Lublin. I remembered Izik Tepper and his family from home.

When Tepper saw Schiff and me he almost fainted. He did not know of any survivors from Borysław. We sat all night on the floor while I told him about the Jews of his home town.

I stayed at the Soldiers Home, and joined the staff. Here were only Poles and Jews, no Ukrainians. All of them, without exception were good to me. Itzek, Schiff, and I sat all night on the floor there at that house and I told them about what had happened in all the years since we had seen each other. In 1939, they had both enlisted in the army and since then had not heard or seen anything of what happened to Borysław and its Jews. So I talked with them and the three of us cried.

I told them how in 1941 at the beginning of the war between the Russians and the Germans, the Russians burned all the houses near Kopelnia and Wasko, how their houses were burned, how Itzek’s father broke his leg but was saved from the fire and taken to Nowy Swiat where the Jewish doctor Hermolin treated his leg.

Again I told him the story about the killing, the ghetto, how his father mother and sister were captured and sent all to Belżec to be exterminated, and also about the ghetto in Borysław and the hard life in the labour camp. In this way we sat until morning; they wanted to hear it all.

I told Schiff about his wife and what happened to her during the German occupation. Itzek Tepper had changed his name, like lots of Jews back then, to Ignatz Teprowsky, which sounds like a Polish name.

The commandant of that house was a Jewish Major named Zblodowsky. Almost all the officers were Jewish with Polish names. They had all returned from Russia. The house was a very active place and very noisy. There was a musical ensemble there with a symphonic band, actors, and singers. All were soldiers. There was even a small band of seven musicians that we called “our seven". Every night they put shows on. Sometimes the shows were open to the public for a small fee. The soldiers were invited free of charge, of course. There were directors, costume makers, scenery and props people. There was also a large kitchen for the staff. Since I had not changed my name to a Polish-sounding one, everyone knew I was Jewish and wanted to help me, not only the Jewish soldiers but also the Poles.

In those days Lublin was very crowded with many Jewish refugees from many counties. The army was confiscating flats for its soldiers and officers. They took a room from each family to house the officers. Lublin also had an academy for officers and sergeants. They used me, a civilian and a Jew, for various errands. I remember a colonel in the army who needed errands done when his mother was supposed to come to visit. While I helped him, I lived quietly in the soldier’s house for couple of months. I met with Żelonka from time to time. He had not found any of his family alive, so he rented a room, and oaid a great deal for it. Apparently his house in Lublin had remained intact. There had been a treasure hidden in its basement and before he left, he retrieved it and was able to manage well financially.

In January 1945, while I was in the Soldier’s Home in Lublin, a person named Reiter told me that while he was in Kraków, he met a woman survivor from Borysław named Holda Liebling. She informed him that my mother was alive in Auschwitz. The commander of the Soldier’s Home, Major Zblodowsky provided me with an official letter from the Polish government. It said that I was traveling to Auschwitz to find my mother and asked each local authority to help me with transportation, lodging, etc. Major Zblodowsky provided me with an officer’s uniform and suitable ID. This was an important document; it helped me all the way to the camp. I took the train to Kraków and found lodging. Since the railway tracks from Kraków to Auschwitz had been damaged, the only way to get to the camp was with a coach. I hired one for 1,000 zlotys, a lot of money for such a short trip. We left in the morning. It was one week after the liberation of Auschwitz.

We stopped in town on the way. I presented my papers to the town’s commandant. Because of my document, they provided a horse and food. In the evening, we arrived in Auschwitz and stayed overnight in a nearby village. We presented our papers to the two Russian guards at the camp’s entrance the next day. On the strength of my letter, the guards let me enter and I was led to the camp commander’s office. I showed him my papers. He found it unusual that a son would be coming to find his mother. I was advised not to hurry because the health of the inmates was fragile. Several Russian soldiers accompanied me from block to block. In block ten, several soldiers went ahead, entered the block and shouted: Markel! One woman answered that her name was Markel. The soldiers did not want to tell her that her son had arrived, fearing that she would suffer a heart attack. Instead they told her that a telegram arrived for her from her son and that he was on his way to visit her. Her joy was immense. The soldiers suggested that I wait a while. After a half an hour I could wait no longer. The general and a military doctor entered with me. My mother lay on one of the platforms and another woman next to her lay dead. Later I found out she was from Yugoslavia. My mother recognized me immediately. I recognized her, even though she weighed only thirty-two kilograms. I cried, as did the soldiers with me. It turned out that my mother had been ill when the Germans had evacuated Auschwitz and could not walk. The Germans threatened to burn those left in the infirmary but the Russians arrived before the Germans could accomplish this. The Russian liberators transferred the sick from Birkenau, where the buildings were made of wood, to Auschwitz where they were made of bricks.

The soldiers brought clothing for my mother and carried her on a stretcher to the coach that awaited my return. Many of the inmates accompanied us to the gate to share in our joy. I thanked the Russian commander and we started our return journey. We stopped to visit the Poles that had helped us on the way to Auschwitz. They again provided food for all of us. We rested and continued our journey reaching Kraków in the evening. In Kraków, we visited a Jewish man whom I had met on my way to Auschwitz and stayed with him for two days. Then we continued on to my apartment in Lublin. The next day, Major Zblodowsky sent a military doctor to examine my mother. He took X-rays and found that she lacked calcium in her leg bones. The treatment he prescribed took a long time but within two months she was able to walk with a cane. As for my father, she told me how the men had been separated from the women as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz and therefore she did not see him again. After long searches at the end of the war, I found out that my father had been sent to Mauthausen, Austria where he died, as witnesses told me, during a roll call two weeks before the end of the war. I remained in Poland for one year while my mother recuperated.

In August 1944, after I had been released from the Nazi enemy and before I found my mother in Auschwitz, I felt very alone in the world. I remembered the postcard that my aunt Molly had sent before he war from the U.S.A and I thought that I must find her. Through an acquaintance, I received the address of a man named Egit from New York. I wrote and asked him to send me Aunt Molly's address. I mentioned in my letter that I was alone and did not have another relative in the world except for her. I did not know this aunt personally or even if she was still alive. To my surprise, I received a reply letter from Egit giving me Molly's address. You cannot describe in words how great my happiness was.

A wonderful correspondence began between us. In addition, my aunt sent me food packages that were, at this time, very valuable merchandise. Molly wrote in her letters that she had received a letter from her nephew, Frida's son, telling her that he was serving in the Russian army. However, she did not hear from him again. It seems that he was killed in one of the bitter battles against the Germans and the Russians did not know whom to notify about his death.

My aunt Molly sent two applications for an immigration certificate to the U.S.A. for me and for my mother. My uncle, Markus Prince, who worked as a hatter, was not successful in his business at this time but despite that, my aunt sent the certificate.

Mordecai Markel in Germany

in 1947.

My mother and I passed the hearing we had at the American consulate. We waited to receive a certificate allowing us to be part of the quota, the number of Jewish immigrants from Poland who could receive approval every year. We waited for two years; the certificate did not come. Then, after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, we decided to emigrate to Israel and forgot about America

We planned to go to Israel via Germany. In 1946, we stayed in the UNRA refugee camp in Berlin and were stuck there until 1948, when we made aliyah to Israel and I had the opportunity of participating in the war of liberation. Today my mother is eighty-nine, has grandsons, and great grand-children. She is healthy and mentally sound.

In Israel

I remembered that some of the Markel family lived in Haifa, my father's cousins who were mentioned above. The families had corresponded a little before the war. Destiny then brought me a messenger, a resident of Haifa, Jacob Almogi, who came to Berlin. I asked him to locate a man named Matito Markel in Haifa. To my great happiness, the man told me that Matityaho Markel was a famous man, who was an engineer in the Hadar Hacarmel Committee at Haifa City Hall. And thus began my first step towards Israel.

When I came to Israel, I knew about my grandmother's entire family, all the Markels from my grandmother's house, the cousins and their families. After marrying Naomi Ribacki, Matito Markel had raised a family in Haifa. Their son Modi was born 1948. Today he is married and has a daughter. He works as an economist and lives in the city of Givatayim. His siste, Mija, who was born in 1946, is very talented. Today she is the Dean of the Faculty of Administration and Management in the Technion in Haifa. She is married to Lifa and has a son Adi and a girl Mor, who is married and has two daughters. Thus the Markel family continues to thrive. The Nazis did not succeed in exterminating it from the world.

Jota was married and gave birth to a son and a daughter and later had grandchildren. All of them live in Netanya. She herself is in a nursing home now. In 1945 after the Second World War, the second daughter Nosia was married in Poland at the age of seventeen to a handicapped soldier from the Russian army. Her husband's name is Frank Polek. They emigrated to New York with their two sons in 1948 and were united there with the family of her husband's father. They did well in a laundry business and bought a nice house in Hudson. Nosia suffered from terrible tragedies. Frank died three years ago and their son was killed two years ago in a car accident. However, Nosia recovered and was consoled by the fact that she has wonderful grandchildren. Life goes on and so does she, according to her words. I used to correspond with her and we talk on the telephone. She visits Israel every year to see her sister and me. I love her very much because she is a sweet woman. She is in fact my second cousin (our fathers were cousins) from the family of our grandmother.

The daughter of my father’s half brother, Moses Birnbaum, whom I mentioned above, had worked for a Polish man and survived. After the war, she married and gave birth to two daughters. In 1957 they came to Israel. My mother kept in touch with them. They visited me in Haifa and I attempted to help them as much as I could at that time. The oldest daughte, Pela stayed as a guest in my house for a week and told me that she had finished three years of her studies in Poland. She had studied medicine at the university and continued here in Israel at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She had little money and lived in the student's residence. Each month I sent her an allowance of thirty lira (in the year 1957-1958) and also asked my mother to add thirty lira from her pension from Germany. Thus, for one year we sent her sixty lira as a yearly allowance. She finished her medical studies and was appinted to the staff of Hemek hospital in Afula. There she met a gynecologist Dr. Zokerman, married him and had two daughters. My mother was at her wedding. They have done well in their professional lives. Her husband is the Professor of Gynecology at the Rabin Medical Center .

I mentioned that the two brothers of my grandmother Markel had moved to Israel before the war. One of the brothers settled in Haifa and had two daughters Chawa and Zelda, and a son Mates Markel. Chawa married a man named Plot. They did not have children. Zelda married a man from Petach Tikva, whose name was Yosef Porat. He worked as the manager of the education department in the Petach Tikva city hall. Three children were born to them: Zvi, Rivka and Tali. All of them are married and have children. Zvi Porat works today in the aviation industry in Petach Tikva. Riki works as a special education teacher and also resides in Petach Tikva. Tali lives in Haifa and works as a teacher in the Leo Baeck high school.

My aunt Molly and her husband Mordecai Prince of New York are no longer alive. Their eldest son, my cousin Martin Prince, also died. His wife Doris survives and his children and grandchildren. The youngest son Sidney lives in Florida with his wife Adela. They have two sons, Jeffery and Richard and a daughter Denise. They are doing very well. I keep in touch with them regularly by telephone and letter. Sidney visited us twice in Israel and we enjoyed our meetings very much.

I hope I have succeeded in attempting to reconstruct all the horrors that had happened to our large, extended family. The war and the Nazi occupation in our area was a very real hell for our family, my father and mother, my brother, Shamay and me. Soldiers burned our house and all its contents. I was transferred with the all the city’s Jews to the ghetto in which I experienced all the horrors of the cursed Nazi occupation: hunger, plagues, beatings, and heavy physical labor. In one of the many kidnappings of the Jews by the Nazis, the Germans shot my brother and killed him when he was only sixteen. My father and I transferred his corpse to the Jewish cemetery in the city but today this cemetery is completely ruined and my brother’s grave has disappeared.

But the glass of poison overflowed when we were transferred to Auschwitz in cattle cars. Because I was able to run from the train, I was able to stay alive. For me, my escape was as miraculaous as the coming of the Messiah.

It is worthwhile reflecting on some of the other effects of the war and the persecution of the Jews. With the occupation of eighteen European states by the Nazis, the Germans promised the European people that cooperation regarding the final solution for the Jews would be very profitable for them economically. All the property of the Jews: real estate, houses, factories, and businesses would be transferred for their benefit, as well as the funds, the securities, the jewels, art objects, all that had been deposited in the European banks in that period. Above all, they would be rid of the Jews but not before taking advantage of them in hard labor.

It was a real hell for the Jews. Everyone gave up his immovable property and those who succeeded in hiding some money or gold and jewels endured the humiliation of search and robbery. Golden teeth were even plundered from the bodies. To this day, there are great fortune in money, tons of gold and million of dollars and other foreign currency that remains in the hands of others. All the European states took part in this process, without exception. For all of them the deal was worthwhile. Thus, our people's property was robbed and the crimes have not been punished.