-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Mlynov and Mervits During WWII

***

(return to Phase I: The Russian Occupation)

Phase II: From German Occupation to Ghetto Liquidation (June 22, 1941-October 8, 1942)

On Sunday, June 22, 1941, Hitler broke the non-aggression treaty he earlier made with Stalin. The German army attacked and quickly rolled across the half of Poland held by the Soviets. The attack, known Operation Barbarossa, surprised everyone including Stalin.

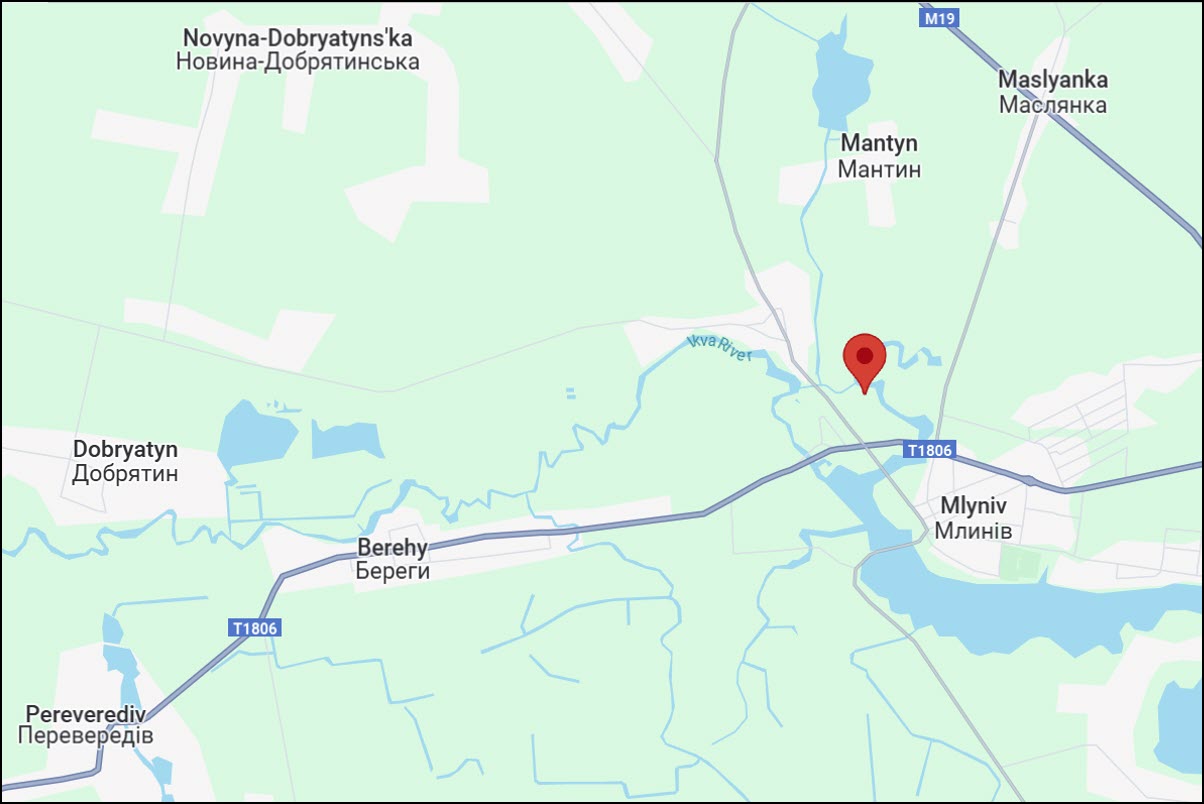

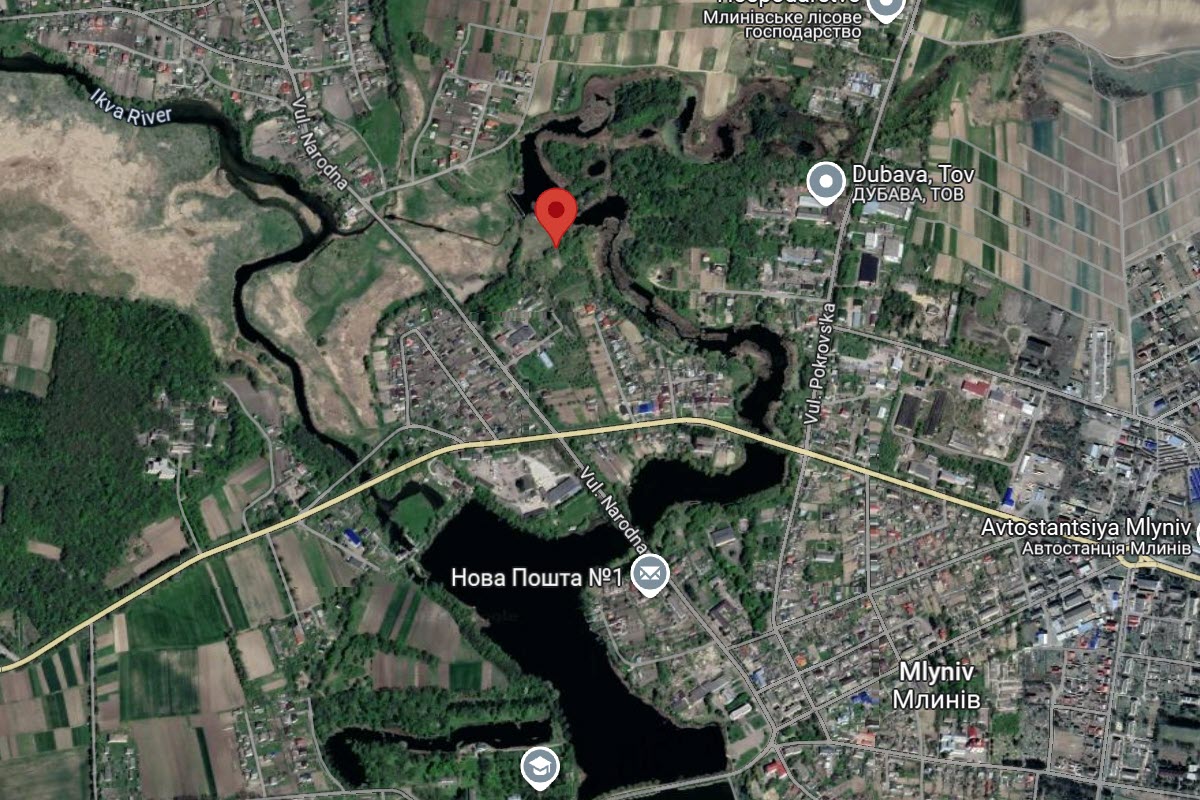

The Russian airfield was bombed outside of Mlynov that first morning, Sunday June 21, and the Germans appeared in town by the evening of Tuesday, June 24th. The German occupation lasted until Oct. 8th (or 9th), when the ghetto was liquidated of its Jewish residents. The following account pieces together one narrative of events in the first-hand words and memories of survivors as found in the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial Book, family memoirs, and video interviews.

Contents

The Airfield Bombing (June 22, 1941) | Fleeing Again | Summer of 1941 | The First Killings | Death is Normalized | Chaia Kipergluz and the Roundup of the Young Jewish Communists | Confiscations, Murder and Dehumanization | News of the Ghetto / Commerce in Certificates | Passover 1942 | Judenrat and Workers For Rovno | The Rescue of Asher Teitelman | The Mlynov Ghetto (April-October 8, 1942) | Underground Resistance | Nearing the End | The Plight of Chana Klepatch | Other Efforts To Escape | The Last Few Days | The Final Day | The Mass Grave

***

The Airfield Bombing, June 22, 1941

Four survivors from Mlynov and Mervits wrote about the bombing of the Russian airfield just across the Ikva River from Mlynov. The bombing began on Sunday, June 22nd in the hours before dawn. A second bombing of the town followed in the afternoon. Several homes were destroyed and several people were killed and injured in the second bombing. By Tuesday, June 24th, German soldiers entered town.

The most detailed account of that first day and the week that followed comes from survivors, Asher Teitelman, and his father Nokhum (Nahum) Teitelman. Both men wrote essays for the Memorial book and Asher's life story was recorded later in a book form. (Read more about the Teitelman family.)

***

Asher Teitelman Recalls Day 1

Asher was born in Mlynov in 1921 and his father Nokhum was born there in 1890. Asher, about 20 years old at the time, was working at the Russian airfield the day the bombing started. "That very moment," he recalled later in life,

I was at the airfield. Fortunately, I was only lightly wounded. In that place, total confusion broke out. People screamed, cried, and fled with fear in all directions. I also fled…I reached the river, and I saw the bridge destroyed. I climbed on the parts of the bridge that remained hanging. With a great effort and all my remaining strength, I managed to cross the river. I reached the town, turned and walked towards my house. Along the way, I realized that most of the houses were empty of people. I entered my home. To my joy, I saw that Mother, Father and all my siblings had not fled. They waited for me. The emotion was palpable. Mother sobbed. (Tomer, Happy is the Man: The Asher Teitelman Story, English p. 19 [original page 21])

Asher also wrote a detailed account for the Memorial book of the confusion that prevailed in town that day and which included the Russian military who were present. "Thus it began," he wrote:

With the breaking of dawn, the town shook from the sound of loud explosions. We thought it was just a military exercise, because there were military bases surrounding us, in addition to the large airfield on the Count's land on the other side of the river. That the war had broken out the day before between the two parties to the [Molotov-Ribbentrop] pact — no one believed this… but when we exited from our houses and the throng of residents gathered in the open areas of the town, and the situation was comprehended, the shock hit us like thunder on a clear day.

“War has broken out” - was heard from all sides. The Germans bombed the airfield, and the local Soviet army was thrown into shock, [but thought] this is nothing but a regretful skirmish. “It is not possible,” the commanding officers responded, “that war has indeed broken out.” But in the meantime, terrible news arrived, each worse than the next.

Shocked and mortified, we stood, group by group, and discussed our situation. We had to plan what to do for the future. Who could have imagined that looting and destruction were this close; that the walls of protection would be removed, that the mighty army of the Soviet Union would retreat completely along the length of the front?

In the meantime, the town and the airfield were bombed four-five times during the day. The large bridge that led to the property of the Count, was destroyed in the bombing, and the passage of vehicles was not possible; those going by foot endangered their lives and crossed it when it was broken up and its whole length was hanging by a thread above the water, but who paid heed to the danger? All the men were brought out by the Red Army to the airfield to fix what was possible to temporarily fix and I was among them. All the time there were sirens and bombings.

What was going on in the town, we didn't know. Only flames and stacks of smoke we saw from a distance and from this we guessed that here and there bombs had fallen. Towards noon, the airfield was bombed in a massive bombardment and it was completely destroyed. There were dead among the residents of the town, Jews and gentiles both included, and some of the military men. Hundreds of people [took cover by] lying down along the shore of the river, by the meadow, and watched the aerial fighting taking place between the Nazi and Soviet planes. After the planes were driven away, a large surge of people fled to the town. The remnants of the bridge were going up in fire, and many succeeded to cross over to the town on the broken remains of bridge that still were floating.

And the town? — most of the residents already had fled from it, and those who remained were waiting impatiently for the return of their loved one from the airfield. The town emptied quickly, the bombed houses burned and the roads were destroyed. Towards evening, the Nazis took control of the airfield and on the next day they left again.

The second day passed quietly in the townlet that had emptied entirely of its residents, who had scattered to the rural villages and the fields. On the third day, rumors spread by the Soviet army, that they had repelled the invader, and that there was no immediate danger to our area. The rumors influenced [opinion] very quickly and the residents began to stream back home. Indeed, during the day it seemed, that the danger had passed.

But how astounded we were in seeing in the darkness of dusk German reconnaissance units wandering around between the houses. Panic seized the residents of the townlet and, in the blink of an eye, a strong flow began towards Mervits, and from there to Polish farming communities in the area. All night and during the fourth day, the migration occurred, and from afar the sounds the Lutzk bombardment and its surrounding reached us; The burning town lit up the surrounding area.

During the night, the Red Army retreated after hard fought battles on the north side of Mlynov, and evacuated the area. A number of buildings were damaged and among them the new flour mill of Rabbi Joseph Gelberg, of blessed memory. In addition, the supply of electricity to the town was damaged.

During the middle of the fourth day, the soldiers appeared in the area. An army that was large and numerous, with vehicles and by foot, gained control over everything. Tragedy fell upon us, we tumbled and couldn't get up. And that is the way it only started… (Asher Teitelman, "The Massive Disaster," English p. 34, original p. 38).

Nokhum Teitelman's Memories of Day 1

Asher’s father, Nokhum Teitelman, also recalled the confusion that first day from his own vantage point.

Early on a nice morning, the 27th of Sivan 5701 [June 22, 1941], I shook off my sleep, got out of bed, and went out into the street. There was screaming, an uproar; we didn't know what was happening. The Russian landing field had been bombed, and we did not know who did it. The Russians were grabbing people out of their beds to make the repairs; my children were among them.

We spoke in whispers. What could this be? We were a little mixed up, and we shivered. This went on until 4:00 p.m. when, suddenly, 18 German airplanes started bombing our shtetl Mlynov. All four sides were burning. It became dark; we wanted to run, but we did not know where. In addition, the children were still not back from work, and only God knew what had happened with them. People ran, but we waited, hoping our children would soon return. And so they did. Our children came running back, barely alive.

My Asher was black, his face covered with dirt, because a bomb fell in the place where he labored. With him, in that place, was Shaye the psalm-chanter's son-in-law. A rock tore off one of his hands, and he was saved by a miracle. (Nokhum Teitelman, “In the Depths of Hell,” English p. 299, original p. 314).

When Asher finally reached home, the Teitelmans quickly locked up their house and headed to Mervits where Asher’s aunt and uncle, Sonia and Mendel Teitelman were living. They found them outside of Mervits in the fields where they witnessed an aerial fight in the skies above Mervits. Bullets were whistling all around so they fled from Mervits too.

As the Teitelman group continued walking, they could see the town of Lutsk burning to the north. That first day after walking 8 km along the road they got to the village of Stomorgi [today Stomorhy, Ukraine]. There were many other Jewish refugees there already, most of whom fled or were evacuated ahead of the German invading forces from points further west. The family didn’t find a place to stay there. The following morning they continued to the Polish town called Pańska-Dolina, that was surrounded by forests. In a foreshadowing of their later experiences, they stayed in this same Polish town which subsequently harbored Polish partisans and played a critical role in their own survival.

News and rumors were traveling fast. A rumor reached them that the Germans had retreated and that the Soviets were again in control of Mlynov. So the family made the decision to return to home on Tuesday, June 24th. They found their home intact as left it. That evening, Tuesday, June 24th, they saw men riding into town on motorcycles. They were German soldiers in the disguise of civilians. (See Tomer, Happy is the Man, English p. 19 [original page 21])

***

***

Yechiel Sherman Remembers Day 1

Yechiel Sherman, a peer of Asher's, was almost 19 years old when the airfield was bombed. He was living with his younger siblings in the house next to his grandmother's and he was the man of the house. His mother had passed away several years earlier and his father had moved to Dubno after remarrying. Yechiel disliked living in Dubno with his father and had moved back to Mlynov in the meantime. For the summer vacation of 1941, he was joined by his younger siblings.

In an essay for the Memorial book in 1970, he also vividly recalled that morning.

It is 4 am in the morning. I had just begun to dress to head to work. Suddenly I heard a loud, strange noise. It was like the houses were moving from their foundations. I went outside quickly but didn't see a thing. I began walking towards the town center. By the home of Rabinovitz, I already saw several Jews standing and saying that they had bombed airfield on the other side of the Ikva River.

Already by 9 o'clock that same day, talk began about the war that the Germans declared against Russia. Many people were standing and talking about this disaster, even though they couldn't relate any details. But already by 2 o'clock in the afternoon, when I walked in the direction of the general store, which at that time was opposite the house of Aba Grinshpun, I heard and suddenly saw suddenly aircraft approaching from the direction of Dubno and beginning to drop bombs on the airfield and afterwards also on Mlynov itself. Already, by this time, some people had been killed and the panic had broken out. Tremendous fear pervaded everyone. They began to run from the town in every possible direction. (Yechiel Sherman, "Taking Leave of Home.")

Yechiel returned home from work that evening. Details at that point are a bit fuzzy. In his initial telling of the story, which was probably fresher in his memory, he fled Mlynov with his grandmother, his aunt and siblings, for the nearby village of Slobada where they had a Ukrainian acquaintance.[1] They stayed there in his hayloft along with other families from Mlynov. In his later account from 2003, Yechiel indicated that his siblings were not home when he returned from work the day of the bombing. He went out to look for them on his bicycle but he couldn't locate them. He later learned his brother may have died in the bombing and was uncertain what became of his sister. In both versions, he and his grandmother and aunt fled to the nearby village.

"The following day [in the village]," Yechiel recalled, "we began to analyze the situation, but in the morning, we still lacked information that could help us with this."

We observed only that the [Russian] military quickly made an escape in the direction of Russia. What to do? I was then 18 — and it was my opinion that there was no compelling reason to remain here and wait for the Germans to arrive. A clear and decisive sign to me was [the fact that the man]— with whom we stayed the night and in whose shade we spent time — already in the morning drank vodka to the wellbeing of Germans and the life of Ukrainian independence. We grasped that our end would be bitter.

That same day, the 23rd of June 1941, I bumped into Pinhas Klaper, Moshe and Yehuda Veiner, Gertnich Koftziav — and we decided to flee at night towards the Russian border. I alone went back again to Mlynov to convince a few young men to flee together with us, but I was not successful. Among others I met was Icek Kozak and asked him to permit his son Ruben to go with us — but he refused. I returned to Sloboda.

Along the way, I met Yehezkiel Liberman, who lived along the road to Sloboda, and he asked me, “Yechiel, where are you going?”

I told him that I and a few other friends were fleeing to Russia. He started persuading me not to flee: The way was full of danger, and we were liable to be killed. I didn't heed him, and I continued to the village of Sloboda. I recounted what had been done in Mlynov and people’s opinion about our fleeing — Only members of my family,among them my father Moshe Sherman, favored my fleeing. (See Yechiel Sherman, "Taking Leave of Home," English 322, original p. 344.)

Yechiel and four friends fled East on bicycles and made it into the interior of Russia where they survived, in a story that Yechiel recounted later to family in 2003 (Koren, Story of Yechiel Sherman, 2003). Yechiel's grandmother, aunt and his siblings, Yoskah and Sheindel, did not survive. Later, after the liberation of the area, he would be reunited with Ezra who managed to escape and miraculously survive.

***

***

Yehudit Mandelkern Remembers Day 1

Another survivor, Yehudit Mandelkern (married name Rudolf), recalled the bombing and the moment the Germans entered her house that week. Yehudit was one of seven children in the Mandelkern family. She and her sister Fania escaped the Mlynov ghetto together and contributed a comprehensive narrative from the start of the German occupation until their return to Mlynov following their liberation. Yehudit recalled that

Already on Sunday, June 22, 1941, with the outbreak of war between Russia and Germany, our little town, which had in it a Soviet airfield, was bombed. My mother was injured in her leg. During that same bombing, a number of people were killed, and several houses destroyed.

On Tuesday, June 24, 1941, in the afternoon, the Germans entered the town. Before their entrance there was a small dogfight. The Soviets fled town on Monday [June 23rd] without putting up resistance. At 5 o'clock, on Tuesday afternoon, the first German soldiers entered our houses. My mother who was wounded, lay on the floor out of fear from the bombardment; my brother, Moshe, of blessed memory, was lying down pretending to be sick. The five or six soldiers who entered obscenely asked for pork. We responded that we were Jews and didn't have any pork. We offered them buttermilk. But when they heard we were Jews, they rudely shattered the pitcher and left the house.

A day or two after the occupation, they had already published a proclamation in writing, in Ukrainian and German, that Jewish men and women from age 14 and older were obligated to report to the market square for labor, equipped with work and cleaning tools. Whoever did not present themselves — would be shot. Immediately, the Ukrainian police was organized, its recognizable symbol was a blue-yellow ribbon on the left sleeve. The women were sent usually for cleaning work and the men — for digging and field work on estate of Count Chodkiewicz, who had disappeared already by 1939. (Yehudit [Mandelkern] Rudolf, "Life Under the Occupying German Government" English p. 269, original p. 287)

***

Fleeing Again

The day the Germans entered town (Tuesday, June 24th), Asher's family decided to flee again. They gathered up a few things and fled again by foot back to Pańska-Dolina to the home of farmers they knew and requested food and shelter. The famers gave them some food, but they were afraid to shelter them because of the Germans. So the Teitelmans entered the forest around the village and there bumped into siblings of Asher’s mother Rokhl (Rachel) (her brother Nuta and her sister Chaika who had three children). The group stayed in the forest until Friday [June 27th] and then decided to head home.

There were fifteen of them walking along the road when they were stopped by German soldiers along the way. The soldiers lined them up along a wall, commanded them to raise their hands and turn to face towards the wall.

“We are going to kill you,” they said. “You are our enemies.”

Two of the officers spoke Czech. Since Asher’s Aunt Chaika knew how to speak Czech, she turned to them and began to speak to them. She told them that they just wanted to go home! The soldiers deliberated and then told their captives to be on their way. Nokhum recalled,

On the way we saw how Christians were carrying off Jewish possessions. We even recognized our own things, but we kept silent until we came to our house. When we went inside, it was worse. Everything was broken. We had been robbed, and the house was full of feathers because the thieves shook the feathers out of the pillowcases, and they packed everything that was in the cupboard in them. The store that had been full of grain and some flour was cleaned out. We were left with the four walls. (Teitelman, "In Depths of Hell," English p. 300, original p. 315).

Asher added some additional details:

Father and I entered first. In the living room, I recognized familiar faces: A farmer and his wife stood beside full sacks of clothes and other belongings of ours. Father exploded in a loud voice, “Joachim, “Even you are among the thieves!” They left all of it and fled. (Tomer, Happy is the Man, English p. 21, original p. 23)

Nokhum had more to say:

But that was not enough. Soon several Germans marched into our house. They asked what we were doing there, and who we were. At first they said they were searching for weapons, but they meant something else. They started to bother [my daughter] Shifrele, even though she was still a child. We bought off the villains. (Nokhum Teitelman, “In the Depths of Hell,” English p. 300, original p. 315)

Asher's family remained in Mlynov that Friday and Shabbat [June 27th and 28th] but they were too frightened to go to the synagogue.

The First Sabbath in Mervits As Remembered by Bunia Steinberg

Survivor Bunia Steinberg (married name Upstein) recounted to her daughter what the first Sabbath after the German invasion was like in Mervits.

The terrible trouble started on the Sabbath. Following rumors that the Nazi Gestapo attack only men but not women, my mothers’ brothers went and hid in an orchard and my mother stayed alone in the house. Suddenly, the Nazis broke into the house and began to cruelly beat her with rubber clubs. They found the males hiding in the orchard and beat them too, without mercy, and afterwards took the family out into the street. Thus, they went from house to house, beating them and taking those hiding in the houses out to the streets. While my mother was standing in the street, she saw the Nazis cruelly beating her mother even as she was bleeding.

My mother ran to protect her, but she was shoved back into line by the Nazis. The Nazis forced everyone standing in the street to run to the neighboring Mlynov and had them stand alongside the post office, which the Gestapo had made their headquarters. The men with beards were taken from the line; their beards were cruelly sheered and they were beaten without mercy. Afterwards, everyone was ordered to perform exercise drills: [repeatedly being ordered] stand up, sit down. (Baruch, Struggle To Survive")

***

The Summer of 1941

After the initial shock of the bombing and rapid German occupation, several searing events took place that summer. Asher provided an abbreviated version of events that probably telescoped several into a shorter timeframe. In Asher's recollection,

on Sunday morning [June 29th, following the appearance of the Germans in town], Ukrainian police passed by on the road and called everyone out of their homes to the town square. Hundreds of Jews obeyed and came out. That same morning some Jews were killed. Many Jews, mostly the younger ones, were taken for labor by the Germans. All the Jews were required to tie on a yellow patch...I was taken to the area of the Count’s mansion. There were two mansions. One was destroyed by the bombing. The second remained still standing. They demanded that we clean up the area. (Tomer, Happy is the Man, English p. 21, original p. 23)

***

Yehudit Mandelkern on the Summer of 1941

Yehudit Mandelkern recalled the early period too. In her memory, the Jews were intially identified by a white ribbon. The yellow patch came later. She wrote:

Immediately after the occupation, the Jews were ordered to don a white ribbon with a blue Star of David (Magen David) on the sleeve. A number of months later, in the fall of 1941, they were ordered to switch the white ribbon with a yellow patch on the back and breast. This obligation fell on children 12 and older. (Yehudit [Mandelkern] Rudolf, "Life Under the Occupying German Government," English p. 269, original p. 287).

Like Asher, Yehudit recalled forced labor starting immediately, enforced by Ukrainian police who were organized to support and extend the German terror. With few exceptions, Ukrainians in general were willing participants since they resented Polish rule and aspired to have their own Nation State. They thought and hoped that by supporting the German efforts, they would be rewarded with their own national entity. Yehudit recalled:

A day or two after the occupation, they had already published a proclamation in writing, in Ukrainian and German, that Jewish men and women from age 14 and older were obligated to report to the market square for labor, equipped with work and cleaning tools. Whoever did not present themselves — would be shot. Immediately, the Ukrainian police was organized, its recognizable symbol was a blue-yellow ribbon on the left sleeve. The women were sent usually for cleaning work and the men — for digging and field work on estate of Count Chodkiewicz, who had disappeared already by 1939.

Some of the people — about 200 — who were sent to labor, were directed to the property of the Count Liudochowski in the village of Smordva; Jews from the nearby villages of Boremel and Dymidivka were also taken to that same estate. The head of the estate was Volksdeutscher Grüner, a cruel sadist who would wake the men up many times at night and command them to run. The running required running down steps. During the descent, he would whip the runners with an iron whip so that the men would fall down the stairs. (See Y. Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," English p. 269, original p. 287).

***

Nokhum's Memory of Forced Labor

Asher's father, Nokhum, for example, was sent into the fields for agricultural labor during the summer.

We got used to it. Early in the morning we ran to the main plaza, and we waited to be taken to various jobs. Soon Germans came for laborers, and they divided us up. One village needed 50 Jews, another needed 100, and so on, until the plaza was emptied. The Christians stood at a distance and laughed. A few even taunted the Jewish merchants...Because aristocrats had many fields around Mlynov, the Jews were distributed for fieldwork at harvest time.... we became land-workers: cutting, tying, threshing, and cleaning. (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” English p. 300, original p. 315)

Individuals like Nokhum, who were observant, tried to observe the Jewish rituals including even fast days during their forced labor.

So we worked until the harvest was done. On [the fast day of] Tisha B'Av [eve of Aug. 2nd to end of Aug 3rd, 1941], I was working together with more Jews. For show, we each brought along a bottle of water with a piece of bread, but we did not eat or drink [because of the fast day]. We kept spilling out a little water, so that the Germans would think that we were drinking it.(N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” English p. 303, original p. 319)

***

The Forced Labor of Young Women

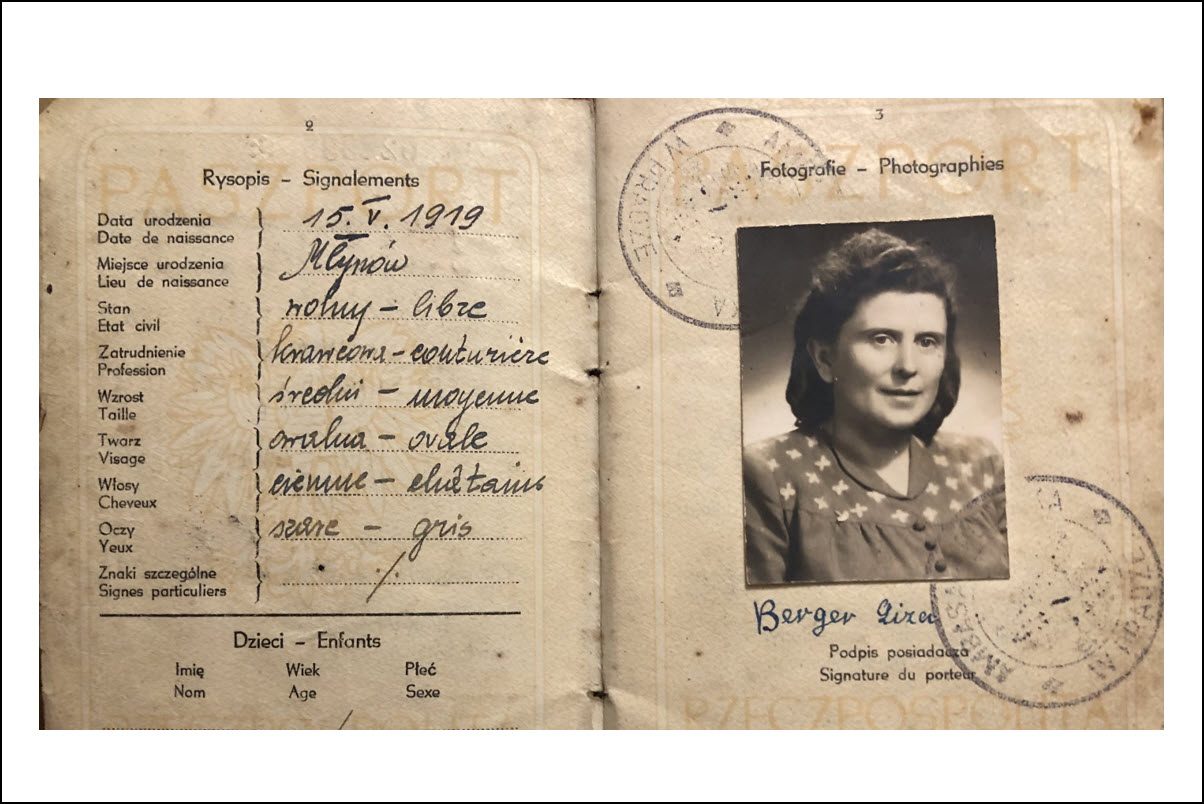

The forced labor of young women was also quite brutal as documented by survivor Liza Berger, remembering her experience from the fall of 1941.

We were about 50 girls, women, men, and children. Girls were chosen to wash the vehicles in the river. 20 trucks were brought in, and we girls stood in the river up to our belts and washed the vehicles, from 10:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m. It was September 1941, and it was very cold, freezing. When we were told to go home, we each received three blows from their guns — that was our pay. When we got home, we had nothing to eat; the farmers had not brought anything into the shtetl that day. (Liza Berger, "I Wandered Hungry and in Pain," English p. 325, original p. 347)

***

The First Killings in the Summer of 1941

"We were fine with the work, as long as we had our lives," wrote Nokhum Teitelman looking back on the early days of the occupation. That soon changed, with roundups, humiliations, and shocking killings occurring in the few weeks following the occupation. Especially horifying was the murder of Mlynov Rabbi Yehuda Gordon.

***

Asher's Memory of the First Killings

According to Asher Teitelman, the killings began almost immediately on the first Sunday of the occupation, the same day he was taken into forced labor, though others identify mid-July as the date of the first killings. Asher recalled:

On Sunday morning [June 29], Ukrainian police passed by on the road and called everyone out of their home to the town square. Hundreds of Jews obeyed and came out. That same morning some Jews were killed. Many Jews, mostly the younger ones, were taken for labor by the Germans. All the Jews were required to tie on a yellow patch.

Rav Gordon was killed that day. They cut off Father’s beard. I was taken to the area of the Count’s mansion. There were two mansions. One was destroyed by the bombing. The second remained still standing. They demanded that we clean up the area.(Tomer, Happy is the Man, English p. 21, original p. 23)

***

The Killing of Rav Gordon and How Nokhum Lost His Beard

Asher was probably telescoping together several weeks of time together in his account and it is possible he may not have known or may have forgotten the story of how his father, Nokhum, actually lost his beard. Nokhum remembered the same events taking place on Saturday and Sunday July 12th and 13th:

I got up in the morning and saw the gifted Rav [Rabbi], Mr. Yehuda son of Mordechai Gordon, righteous man of blessed memory, passing my house, and walking [and not riding] towards Mervits, so as not to profane the Sabbath.

I thought, “perhaps I too should try to leave town,” and I walked straight to my brother-in-law, Yaakov Schichman, of blessed memory. He was living at the end of town and suddenly, when I was already there, I heard shooting, and I went outside with my brother-in-law and we hid among the grain in the field. The grain was already reasonably tall, and that same Shabbat the bitter enemy entered the synagogue of the Trisk Hasidim in Mervits and killed Motel Tesler. He was already close to one hundred [years old]. [They murdered] him and another poor man.

Near evening I returned home, and I met older men along the way, among them was my uncle, R. Chaim Meir [Teitelman], whom the bitter enemy had reduced to younger men by removing their signature beards … I entered home safely, with great trepidation, because they had already told me what had happened to them that same Shabbat.

The following morning, I got up and took the scissors and cut my own beard and went with all the others to their respective work. By the time I returned in the evening from work, we had already heard about eighteen dead, and among them, the gifted and holy Rav Yehudah Gordon, and thus fulfilled in us [the Scriptural verse]: “you shall be in terror, night and day, with no assurance of survival” (Deuteronomy 28:66). (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” English p. 301, original p. 316)

Nokhum recalled the exact date these events took place because he was attuned to the cycle of the Jewish lexionary. The painful and ironic parallel between the events befalling them in real time and the events described in the biblical reading for that week were not lost on Nahum.

That Saturday, Nokhum recalled, was the 17th of Tammuz (July 12, 1941), what Nokhum called "the Black Sabbath, Parasha Balak." The 17th of the month, Tammuz, is a fast day on the Jewish calendar when Jews commemorate how the walls of Jerusalem were breached by the Romans before the destruction of the Second Temple. In 1941, the date of the fast (17th of Tammuz) fell on the Sabbath, so the fast day was postponed to the following day in accordance with Jewish law.

That particular Sabbath of 1941 Jews normally would have read the Torah portion called "Parashat Balak" (Numbers 22:2–25:9) if there had been prayer services in synagogue that day. Since Nokhum saw Rabbi Gordon heading to Mervits early in the morning, it seems likely synagogue services had already been suspended in town. In any case, Nahum was still keeping track of the lextionary anyway. He knew that the biblical passages for that day described how Balak the king of Moab requested that a prophet named Balaam curse the Israelite people. But when Balaam tried to do so he ultimately failed because God intervened in various ways. Nokhum doesn't say so explicitly, but he must have been praying God would intervene to stop the Balak of his own time. It was not to be, at least that summer.

***

Sonia and Mendel Teitelman Recount the First Killings in Detail

An even more detailed account of the same events is recounted by Nokhum's first cousin, Mendel Teitelman and Mendel's wife Sonia Teitelman. (Sonia was also sister of Nokhum's wife). Sonia and Mendel lived in Mervits. They began their recollection describing the same murders that that took place on the 17th of Tammuz [July 12th, 1941] and the following day:

Our first 10 slaughtered were eight young people, of blessed memory, from Mlynov and Mervits, plus two old Jews of blessed memory who were killed the day before them on Shabbes afternoon, 17 Tamuz 5701 [July 12, 1941] in the Trisk synagogue in Mervits. One of them was Mr. Motel Grinshpan, called Motel Tesler (tesler meaning carpenter), over 90 years old, and the shammes [sexton] in the Trisk synagogue. He lived there and he was shot there. (Sonia and Mendel Teitelman, "Tragic Tales," original p. 325, English, p. 309).

Recounting the sequence of events, Sonia and Mendel remembered that

In that perilous day, the 17th Tammuz, Shabbes ... not a single creature in the shtetl felt cheerful, even though in the early morning hours we still prayed with a minyan, and I still said Kaddish [a prayer honoring the dead] for my mother, may she rest in peace. The Mlynov Rabbi of blessed memory had a premonition to not be in Mlynov, although up to then nothing had happened.

He came running in the early morning to Mervits and prayed together with us. After praying, he left for Stomorgi [today Stomorhy, Ukraine] to the fleeing Jews there, and he remained with the Keler family, of blessed memory, thinking that when the situation would stabilize a little, he would return home. (Sonia and Mendel, "Tragic Tales," original p. 326, English, p. 310).

According to their account, Rabbi Gordon was killed in Stomorgi along with another Jewish man from Mervits, named Zelig Moravitsky, who was a barber. They were killed there with Jewish farmers who had been resettled there in April 1940 by the Soviets from the town Sokoliki which was further east near Turka. In a different essay they wrote, Sonia and Mendel, mention in passing that Rabbi Gordon "was brought for burial to the nearby village of Kutsa."

What Happened in Stomorgi

Frida Kupferberg, recounts the situation in Stomorgi the day Rabbi Gordon was murdered. At the instructions of a high-ranking SS commander, Zalewski (probably Erich von dem Bach-Zalewski)

the Germans entered Stomorhy from Dubno three weeks after the outbreak of the German-Russian war; that was Sunday, the 13th of July 1941, the 17th of Tammuz, a fast day for Jews.[6] It was a double day of sorrow a[1st as a fast day and 2nd] because the Germans had taken over. They attacked a Jewish house where two families were living. With screams and violence, the Germans forced everybody out into the garden, and then they shot the Jews one by one. The last one shot was Moyshe Fayler's young, very pregnant wife. Moyshe Fayler with his wife and mother; Ester and Shmuel Zinger, Royze Zinger, Leyb Fram, and another boy were murdered.

After that the Gestapo ran into the house of Volf Keler. Volf Keler was a learned Jew who sat and studied Gemara. His four sons followed the same path as their father. The Gestapo forced Volf Keler, his four sons, Moyshe Gelmakher, Mudil Frab, as well as Mlynov Rabbi Gordon, who had spent Shabbes with Volf Keler, to the house where those who had been killed were lying.

Relatives and neighbors were ordered to put the bodies in a wagon and take them to a ditch. Afterwards they followed the corpses in the wagon up until the heaps of excrement before Mervits. There had been an open ditch in that place for a long time. The Jews were ordered to dump the murdered bodies into that ditch. Afterwards the Germans also shot the Mlynov Rabbi, and he fell into the ditch.

The Gestapo took Volf Keler with his four sons Berish, Moyshe, Hirsh, and Shimeon, and another two victims, Moyshe Gelmakher and Moydl Frab, to Dubno. They were thrown into prison, where they were all killed. The rest of the Stomorhy Jews were beaten and forced by another division to Mlynov, where they were distributed for various labor assignments. The horrible events of the 13th of July remained in my soul. A year later, the rest of the Jews from Stomorhy and Hintsharekhe were murdered in the Mlynov ghetto. (See Frida Kupferberg, " Murder of the Sokoliki Refugees" original p. 384, English p. 354)

It is clear that in the early days of the occupation, rumours and misinformation circulated as residents grappled with the early shocking deaths. Survivor Yehudit Mandelkern, for example, heard a different story of Rabbi Gordon's death. Rabbi Gordon, she wrote,

was summoned from his home by the Germans and held a number of days in prison before he was brought out and killed. It was said in town that the Rav knew how to speak German well and therefore they interrogated and tortured him for several days. Afterwards, he was taken outside town and killed. (See Y. Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under the Occupying German Government," original p. 289, English p. 271).

***

The First Deaths in Mervits

That same day Rabbi Gordon was killed, Sonia and Mendel recalled that the first murders began in Mervits:

The first [to be killed] were the two old Jews, Mr. Motel [Tesler] the Sexton and the deaf pauper. Everyone in the entire shtetl, without exception, ran out to the fields at the first shots and hid among the tall ears of corn, which were still standing in the field. Not one happy creature remained in the shtetl. As elderly and deaf and dumb people did not orient themselves so quickly as to what was going on, the two victims remained sitting in their places, eating the tiny portion of tsholent[a kind of stew] that they had prepared the day before. And when the murderers, may their names be blotted out, opened the door and saw them, they shot them both on the spot, leaving them in pools of blood. Then they left to search for more victims.

We first learned about their deaths in the evening when we all, very frightened, returned home. The meaningless death of the two old, poor, innocent people, the first victims, spread terrible fear and great pain throughout the shtetl. All realized that the murderers' goal was to kill people who were in no way guilty of anything, and nobody had to account for the murders. (Sonia and Mendel, "Tragic Tales," original p. 326, English, p. 311).

The next day, the 18th of Tammuz 5701 (July 13, 1941), residents were ordered to gather in Mlynov in the middle of the marketplace for forced labor.

Accompanied with beatings and curses, we were led from there to the Mlynov airfield, not far from the Count's palace. We fixed damage caused by bombs...We were beaten and abused at work, but who reacted to such things?

That afternoon, a German with a gun, "dressed only in a bathrobe," showed up and ordered eight of the young people working there and a few others he selected to line up.

He killed them all with his own unkosher hands. Afterwards, he called the next group. In the beginning, everyone had to dig his or her own grave, and to cover up graves next to them until their strength gave way before being shot. Those who were accompanying the victims finished everything. When they returned, they were unable to speak until nighttime; they had simply lost their language skills.

Icek Kozak Was There That Day Too...

Another survivor, Icek Kozak, was there that day and described that same event.

As soon as the Germans came in, they took us, a group of old and young Jews, to work on the military airfield. Several murderers went over to the people who were working, and they chose the best-looking boys. My children and I were standing a little further away and we saw how the murderers shlepped 10 boys down into the old trenches which were there from the First World War. The boys were killed there; Shloyme Sherman (he was the eleventh) covered them with dirt. Afterwards he came back. Shloyme did not have to be asked about the boys; his face told us everything. I will never in my life forget that day. The mothers in the shtetl looked for their children to come home before night, but they were already dead. (Icek Kozak, What My Family Endured", original p. 354, English, p. 330).

***

Mourning Spread in Town

Sonia and Mendel recalled the intense mourning in town that day:

The mourning spread to everyone in the environment, even affecting a large number of our murderous neighbors, who at that time were not used to such things. The families who had young children, husbands, sons, and fathers of young infants torn from them, lamented the most. Their cries went up to the sky.

A stone could have melted from their tears and hysterical screams. Even a few Christians were astonished. It moved a few of them to respond that the edict had to be a mistake...We saw that it made an impression on the Christians mostly because that was still the beginning. Mass murders were still new. Later, of course, they became a routine habit; nobody paid any attention to such slaughters.

Sonia and Mendel remembered the names of those who were murdered "when we still thought that things would not be that horrible." They were:

- Motl Grinshpan [=Motel Tesler], of blessed memory

- A dumb pauper, without a name, of blessed memory

- Dov Ber Moyshe Litsman, of blessed memory

- His sister-in-law's sister-in-law Pesi, of blessed memory

- His brother-in-law Borukh Likhter from Mervits, of blessed memory

- Moyshe son of Peysakh Kugul

- Moyshe son of Shaye Fishman, of blessed memory

- Borukh son of Fayvish Likhter, of blessed memory

- Moyshe son of Ezris Kulish, of blessed memory

- Moyshe son of Khanina Upstein, of blessed memory

(See Sonia and Mendel, "Tragic Tales," original p. 325, English, p. 312).

***

Death is Normalized

After the initial shocking deaths, killings became normalized as evident in several survivors' accounts. Events began to run together, especially as the local Ukrainian police eagerly implemented the German violence, hoping that they would thereby earn their own Nation State at some point by supporting the Germans.

Asher wrote:

Slaughter and robbery became a daily occurrence. These Ukrainians, who had been thirsty for Jewish blood for generations, experienced in theft and murder, were unleashed to pursue their iniquities. The first shots echoed already in the square of the town, blending well with the sounds of windows breaking and houses being destroyed. Farmers from the surrounding area wandered around with sacks laden with items that Jews had labored to make. And following them their wives and child, laden with whatever came to hand. Under the protection of the soldiers, they passed from house to house, killing, plundering and destroying everything. (Asher Teitelman, "The Massive Disaster (Shoah)" original p. 39, English p. 35) [Page 39]

***

Chaia Kipergluz and the Roundup of the Young Jewish Communists

In the first month of the German occupation, another shocking event occurred. A group of twenty young people were rounded up for being Communists. The Germans suspected them of being loyal to the Soviet Communist government. The deep irony, of course, was that when the Russians occupied Mlynov, the young Jewish Communists had been arrested by the Russians for being Zionists in the past.

Yehudit Mandelkern recalled that "A few days after the occupation, a group of young Jewish boys and girls were arrested for being Communist members in the past: Chaia Kipergluz, Rivkah Ber, Freidel Rivitz, Yenta from the Mandelkern line (my father's sister)."(See Yehudit [Mandelkern] Rudolf, "Life Under the Occupying German Government," original p. 287, English p. 269).

Chaia Kipergluz, who was among those rounded up, was a friend of Yosef Litvak who wrote a tribute to her ("A Memorial Candle [for Chaia Kipergluz]").

Chaia, of blessed memory, was born in Mlynov in 1919. She excelled in her childhood in intelligence and natural talent in many different ways and with much charm... From the age of 9, she was a protégé of the youth movement “The Young Guard” (Hashomer Hatzair)...

She yearned and strove to make aliyah to the Land [of Israel]. Her leaving for a training kibbutz was held up by a family tragedy when her only brother, who was 10 years old, drowned in the river, in the summer of 1938. Her older sister made aliyah before this, and Chaia was not able to leave her parents alone in their heavy grief...

In the early days after the Nazi invasion towards the end of July 1941 she was arrested together with about 20 other Jewish youth – the best of the local Jewish youth – for being “Communists.” All the members of the group were taken out to be killed about 3 days after their arrest following severe beatings by their Nazi torturers and their collaborators from the Ukrainian police men.

May her memory be a blessing and may her soul be bound up in bond of life.

The killings expanded and multiplied and eventually included other groups besides Jews. As Yehudit Mandelkern recalled,

A month to six weeks after the occupation, the Germans sought out members of the Polish parties. They imprisoned 10–15 Polish men and accidentally incarcerated the Jewish young man, Yehuda son of Mordechai Liberman. The Germans misled the families of the prisoners and even accepted packages that were intended for them [from the families], but it became known, that in fact, they murdered all of them immediately after the arrest.

One night, in the early days, the Germans entered the house of the Jewish shoemaker Shlomo Kreimer. He had a beautiful daughter, Rachel – who, upon seeing them, escaped through the window. As revenge for this, the soldiers killed the two parents. Their son, Zalman, who was [laboring] in the village of Smordva, burst out crying when the rumor of his parents' murder reached him. A German soldier who noticed asked him the significance of his crying, and when the soldier heard the reason — shot him to death on the spot. (Mandelkern, "Life Under...," original p. 288, English p. 270).

The sheer number of incidents was completely overwhelming. "It is difficult, very difficult, quite impossible, to bring out every rotten thing on paper," wrote Sonia and Mendel in their essay.

Between one slaughter and the next there were supposed signs that the situation was improving, and we wanted to think — maybe? Maybe this will have been enough? So little by little, about 9–10 months passed, and in that time, in addition to murder, plunder, and deathly fear, the Jewish people were emptied of their gold, jewelry, butter, and everything of value which we had been using the whole time as exchanges for bread. And the mark of Cain, meaning the yellow badge worn in the front and in the back, warned others from far away of every Jew who was seen wearing even clean clothes, not to even think about wearing a fur coat, because that was simply life-endangering. (Sonia and Mendel, "Tragic Tales," original p. 329, English, p.312).

***

Confiscations, Murder and Dehumanization

The Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators found various ways to extend the terror and abuse of residents that summer. Asher's father, Nokhum, was sure he was going to lose his own life when he was assigned to lead a confiscation effort.

One evening, having come back tired from work, unable to straighten up from having tied up wheat, a German burst in the door and ordered: “Come!"

I had to go. To where I did not know. My wife and children were crying, certain that I would be shot, because that was nothing new. The German who took me also took Yoysef Wurtzel, Khayim Berger's son-in-law, and Nosi [Natan] Shiper, the son of Yitskhok Ulinik. We marched in threes. We were taken through the town to the house of attorney Revtshinski. There they started to ask us what our occupations were, and many more questions until late at night.

Back home they had no doubts that we had been murdered, because practically every day several people were taken to the Nantyn [Mantyn?] Forest, and they were shot. After sitting there several hours, I was the first one to be called in. The result: I had until tomorrow 12:00 to deliver 120 cakes of good soap; if not, I would be shot. Nosi: [the obligation of] two kilos of tea. Yoysef Wurtzel: 3,000 cigarettes. And we were escorted home since we were not permitted in the streets after 6:00 pm. When I knocked on the door of the house, those inside thought I had come from the other world.

In the morning, the three wives got together and went through the town to collect the soap, cigarettes, and tea. We put together the products with great effort, because everything had been plundered earlier. For us it was life or death. And God caused the Nazis, may their names be blotted out, to be satisfied with the [effort] of the people. The Germans accepted the goods and ordered us to go home. They took other people right after us: Avraham Gelman, Yankev Golzeker, and Yoysef Gelberg. All curses and calamities came true. (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” original p. 319, English p. 303)

***

The Fall of 1941: More Confiscations and the Judenrat Creation

Confiscations continued into the fall of 1941 and the summer of the following year. Yehudit Mandelkern recalled that "that fall [of 1941] there were two other additional operations: a Gold Aktion and a Furniture Aktion."

During the Gold Aktion the Jews were ordered to bring all their silver and gold implements, dollars and jewelry. They all got receipts for the items that were turned over. After the Gold Aktion came the Fur Aktion — at the end of the summer 1942. After this, Germans arrived with several hundred Ukrainian police and with wagons and confiscated whatever they found — bicycles, sewing machines and regular furniture. The operation stopped suddenly. A whistle was blown, and afterwards some furniture still remained in the spots they had been set when brought out [of the houses] but which they hadn't managed to load on wagons. (Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 289, English p. 271).

Despite these confiscations, Yehudit recalled, there was not a severe shortage of food in the first period.

Most of the families had a stockpile of food. In addition, items still existed which could be bartered with farmers. Somehow each managed, even though bartering was forbidden. Despite the prohibition, the Jews were going to the homes of farmers and farmers were coming to the homes of Jews to barter. (Mandelkern Rudolf "Life Under...," original p. 288, English p. 270).

Yehudit also recalled that the Judenrat (a Jewish council) and a Jewish police force were established in the fall of 1941. The ostensive purpose of these groups was to give the appearance that the Jewish community was being consulted, even though those chosen for the the roles had no real choice in the matter and were burdened with often making painful decisions about to execute the German projects which were implemented by their Ukrainian collaborators.

The Judenrat, Asher wrote, was "the Jewish go-between was the execution arm for all the kidnappings of those sent for labor to the camps in Rovno, Studinka, and elsewhere. They seized warm clothing, furs, gold and silver and in the end also copper and everything made from copper." (Asher Teitelman, "Massive Disaster," original p. 40 original, English p. 36)

Yehudit recalled the composition of the Judenrat and the Jewish Police. The Germans appointed six reputable men, "all shopkeepers and friends: Mordechai Litvak, Chaim Yitzhak Kipergluz (formerly chairman of the community (kehilla) [and father of Chaia Kipergluz who was earlier murdered], a man named Katzevman, formerly secretary of the community, Mordechai Liberman, David the kosher slaughterer (shochet) and Moshe son of Yaakov Holtzeker. For the Jewish police they selected Zelig Zider, Shlomo Schechman, Peretz Tesler, Tzvi Gering." (See Y. Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 287, English p. 269).

Attitudes Toward the Judenrat

Yosef Litvak reflected on the dilemma facing his father who was assigned to the Judenrat.

During the period of the Nazi occupation, he was appointed as secretary of the Judenrat in the ghetto. He carried out this obligatory and wretched role, with integrity, dignity and decency. He was cruelly beaten a number of times by the Nazi rulers for his refusal to fulfill the extortive demands. He died a holy death, with my mother, of blessed memory, at the murderous hands of the Ukrainian police during their attempt to flee from the ghetto a few days before the mass murder of the community... (Yosef Litvak, The Litvak Home," original p. 413, English p. 378).

Not everyone was so undersanding of the Judenrat. In a tribute after the War to a young woman victim from Mlynov named Chana Klepatch, her friend Reuven Raberman, from another town, recalled Chana's outrage towards the Judenrat. The Nazis, he wrote,

infused her with rage, contempt, and deep hatred for all the new humanistic concepts. Springtime feelings that characterized her over the years were transformed suddenly by a bellicose spirit, a vigorous and rebellious resistance, and extraordinary daring. She despised the silence born out of fear [of other members of the community] and didn't leave the Judenrat alone who, in her view, didn't act appropriately given the demands of the hour. (Reuven Raberman, "Chana Klepatch–A Mlynov Tragedy," original p. 277, English p. 258)

How the Judenrat Funtioned

One example of how the Judenrat and Jewish police interacted in the execution of German orders is evident in another operation reported by Yehudit Mandelkern.

In the fall of 1941 (the exact date I don't remember) an order was promulgated to the entire district — to supply 3,000 Jews as construction workers to the town of Rovno to build barracks for the army. The Judenrat in Dubno did not want to send the heads of families and decided to take men from all the towns in the area. In the small towns, they didn't know about the goal of the operations.

Usually, in each operation, there were Ukrainian police who surrounded the small town and the Judenrat communicated the order — to supply a specific number of men. The Judenrat prepared the lists. From Mlynov, they took at that time about 50 men. Men of the Ukrainian and Jewish police went house to house searching for the men on the lists. Some of the men fled to the fields and surrounding forests. In place of those who fled, whose names were on the list, they would take anyone they came across. The arrest of the men was accompanied by crying and wailing.

The men were in fact transferred to Rovno for work. For about two months, news of them was received. After they finished the work, all of them were murdered and not one returned. In order to deceive the youth who were working there, some of them were purposefully sent home for a vacation. These, obviously, confirmed the knowledge that the men were in fact working and were even receiving vacations. (See Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 288, English p. 270).

***

The Rescue of Asher from Rovno

Asher Teitelman was part of the roundup that brought young people to Rivne for labor. His mother Rokhl described the night he was taken.

One night a German policeman came in and took my son Asher out of bed. The Germans did not even allow us to go along to see where they were going. When it became daylight, we went out into the street, and we heard that many young people had been taken, but to where—nobody knew. It took a longer time until we learned that they were in Rivne at forced labor for the Germans.

Sometime later I learned that Yankev Goltseker, of blessed memory, went to Rivne, and after a couple of days he brought home his son Dovid; but his son-in-law was still there. I went to him and begged him to tell me the secret as to how he managed it, but without success. However, he promised me that if he would succeed in getting his son-in-law out, then he would tell me everything.

And so he did. The following week he brought his son-in-law home. He also gave me a note from Asher saying that we should save him if possible. I started to research possible ways to travel to Rivne. It took several days until I was able to get a Christian driver, but he could only go on Shabbes. Understandably, this was a very big problem for me and for my sister Khayke—her son was there too. So I ran to Mervits to Uncle Khayim-Mayer z”l for advice. He affirmed that to save a person one could travel even on Shabbes. Yankev Goltseker explained everything to me, told me with whom I needed to meet, and how to handle everything.

Rokhl made her plans. In addition to saving Asher, she was also hoping to do a good deed by rescuing Lipe Halperin, who was there too. His family begged her to do whatever she could for him, and she told them she would do whatever was possible.

Rokhl dessed as an old peasant woman and paid a farmer to drive her to Rivne. Apparently there was a Jewish woman who was living with the German Commander in Rivne who needed to be approached and bribed. According to Asher's account of the rescue, the woman was known to be "whoring" with the Germans. When Rokhl approached the woman, she sent her to a specific doctor (a Dr. Tsaytlin) to secure a red ticket for Asher, which would indicate he was ill and should be released from labor.

So Rokhl approached Dr. Tsaytlin. She had been to this doctor in the past, before the War and he had helped her recover from a difficult illness. She recounts how the doctor was afraid for his life and didn't really care about money. But she reminded him of how he had healed her in the past and appealed to his mercy.

Rokhl writes:

With tears in his eyes he gave me the ticket, and I took it to the woman. That was Monday. She told me that everything would be done the next day. That cost thousands, but I had enough money. Tuesday I again went to the doctor and begged him to give me a ticket for Lipe. I explained that his mother was a widow, and he supported the family. He gave me the ticket, and I went again to the woman. She had to wait for Wednesday.

Every day people said there would be an Aktion that night against the remaining Jews. I barely survived Wednesday. I took out the two tickets to free Asher and Lipe, and I gave Lipe his ticket and Asher his. I was ready to go home, but Asher lost his ticket! Lipe went home, and I remained with nothing!

So I ran again to the woman and told her she must go to the same office so I could get another ticket for freedom. But as it was already late, and there was nobody to write it up, I had to wait until the next day. Meanwhile I reported the loss to the police, hoping maybe somebody would appear with that ticket. And actually, Thursday, I did receive that same ticket. A Jew had found it and he had brought it to the office.

This is how we, meaning Asher and I, were saved from our deaths for the first time. That same night all those who had been with Asher were murdered. Among them were many from Mlynov. Unfortunately, Lipe was murdered later. (Rokhl Teitelman, "In Those Times," original p. 380, English p. 350).

***

News of the Ghetto Leads To Commerce in Certificates

News that a ghetto would be established apparently was announced already in the fall months of 1941. Yehudit Mandelkern recalled that

In the late fall months of 1941, the Judenrat issued a proclamation indicating that anyone who had a work certificate would not be taken into the ghetto (there was already talk that a ghetto would be established) and would be considered a productive element. Fictitious weddings started between young women and men who were consistently engaged in different kinds of work, and in particular, artisans, including those who worked on farms, who were mentioned above. Afterwards, commerce in work certificates developed. There were different types of certificates. The “best” type were the “iron certificates” that were given to the dentists, goldsmiths, decorators, and all different kinds of artisans, that the Germans openly engaged for their own personal needs. (Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 289, English p. 271).

Possession of such work certificates later helped a number of survivors remain outside the ghetto before the end and go into hiding when rumours started circulating about ditches being dug nearby. When ghetto residents left for work they also had the opportunity to get news and barter for goods and food that were not available in the ghetto.

In Mlynov itself, it was difficult to get these certificates, but trade in them flourished in Dubno. Even before the establishment of the ghetto it was forbidden for Jews to travel from town to town, and the trip to Dubno was therefore unlawful; in other words, the Jews traveled with Ukrainian farmers, disguised [as farmers], and of course with the agreement of the farmers. Every trip like this, therefore, was life threatening. On one unlawful trip, Yaakov Nudler, who traveled to purchase arms for the resistance organization, was grabbed and killed (Yehudit Mandelkern, ) In another instance, "Perel Mandelkern, wife of Yitzhak Mandelkern (living today in Israel), traveled to Dubno to get this kind of certificate for her sister-in-law. Coincidentally, there was a roundup in Dubno and she was swept up and murdered..." (Mandelkern Rudolf, ibid).

***

Nokhum Finds Work

Most people who had certificates and secured work, were pressed into forced labor for Germans. Asher's father, Nokhum Teitelman, was fortunate in securing work initially with a Christian farmer.

Soon after the holiday, around the month of Cheshvan [October 1941], I searched for work with Christians, because many rich, elderly Christians were permitted to take Jewish workers, since the young people were serving in the war. They were allowed to take a few Jews for hard labor, provided the Jews would not be in the town. I needed the earnings of a piece of bread.... I connected with a very well-known Czech, Pani Nokhum, an old man who was alone. He had permission from the authority to take a Jew for labor. I worked for him. He was very happy with me, and I also was happy with him in that time of doom and gloom. It was not that very far; it was 8 kilometers from Mlynov. Friday after lunch I used to walk home, and early Sunday morning I would walk back to him. It was already known that I work for Guladkin. And so the time went, until the 1st of January 1942, when Mlynov was organized. Everyone had to work for the Germans; just a few worked for Christians with permission from the Germans. (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” original p. 319, English p. 303)

Later in January 1942, the Germans started collecting grain for Germany. Nokhum who had expertise in the grain business from before the War was given work back in the town at the repositories. "People were simply jealous of me. The director was a Ukrainian, a big hooligan, an anti-Semite. He was called Flint, but to me he was one of the best...whoever came to his office to register was beaten by the police without a reason. Except for me."

He became a good comrade to me. He found out that I was the best worker and also a specialist. He gave me the key to the repositories, and also the receipts from the grain, so that I became an assistant to him. I used to stand alone [without supervision] by the scale intaking the grain, and also at distributing the grain. The day on which the grain had to be given out was a day of reckoning. 10 trucks, sometimes more, used to come for the grain. So an order was given that all trucks had to be loaded in 2-3 hours; if not, the workers would be shot. One can imagine what kind of rush it became. It was hardly possible to gather everything into sacks, tie or sew them up, weigh them, and load them onto the trucks in time. The sweating laborers were filled with terror that they would take too long and be shot. (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” original p. 320, English p. 304)

Mendel Finds Work

Mendel secured work in the local mill owned previously by Yisrael Vortsel.

I was lucky. As a former owner of a mill, I was grouped with the six families who were employed in Yisroel Vortsel's [alt. Wurtzel's] mill. There I succeeded in being a “useful worker” as was Srolik Vortsel of blessed memory, his brother Mayer of blessed memory, his brother-in-law Fishl of blessed memory, and his cousin Yoysef Feldman of blessed memory from Berestechko. Gershon Opshteyn [Upstein] z”l was a useful carpenter, and Borukh Lokrits z”l was a useful blacksmith.

And we all, with all kinds of tricks, kept our families in Mervits supposedly for work, even in the time of the closed ghetto. There were plenty of death scares in the mill. We had the burden of supplying the population with bread, as far as we only could, and that was fraught with danger to our lives. And still God protected us, and we succeeded, as much as possible, to feed the ghetto with bread. And even though enemy ranks came from many places, wherever there were Jews, there was still a spark of hope not yet extinguished –maybe? Maybe? Maybe God will actually perform a miracle? Because without miracles there was not a single prospect for rescue. (Sonia and Mendel Teitelman, "Tragic Tales," original p. 330, English, p. 313).

***

Passover 1942

As the spring of 1942 rolled around, residents of Mlynov and Mervits contemplated if and how they could celebrate the festival of Passover. Before the War, preparation for Passover was a town-wide event which included "whitewashing the walls, koshering, baking matzas (unleavened bread), preparing shmaltz and eggs, and more."[2] There were different recollections about how residents managed to make matzah that Passover which began the evening of April 1, 1942 and continued to April 8th. In Mlynov, Yehudit Mandelkern recalled that the Judenrat received permission to bake Matzah. "The baking was done in two places and following all the regulations [for baking matzah according to Jewish law]. The Germans did not take an interest in the source of the flour." (Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 289, English p. 271).

Sonia and Mendel who lived in Mervits, and not Mlynov, had a different recollection. They recalled that any talk about baking matzas in 1942 was life endangering if it would be so discovered. But they went ahead anyway.

We kind of thought that the honor of the good deed [of making matzah], and maybe also good wishes, would maybe help, and our wishes would be realized. We baked and we wished, but our good wishes did not come true. To cover up our baking, we, not yet being in the ghetto, gathered in a house which was not on the main road from Mlynov-Lutzk. That was at my brother-in-law Note Gruber, may he rest in peace. His house was slightly hidden by trees on Mikhalovske's land. Several of my relatives baked matzas there, like my Uncle Chaim-Meir, of blessed memory, with his family; my brother Yankev-Yoysef, of blessed memory, with his family; and my Uncle Yankev Gruber, of blessed memory; and my brother-in-law Yankev and Khayke, of blessed memory, with their families. (Sonia and Mendel Teitelman, "Baking Matzahs," 183, English 167).

***

The Mlynov Ghetto (April-October 8, 1942)

Yehudit Mandelkern, who lived in Mlynov, wrote that the ghetto was set up in April 1942. Asher Teitelman, recalled that the ghetto was established between Passover (April 8th, 1942) and the Festival of Weeks (Shavuot) (the eve of May 21st). Asher wrote,

One of the days between Pesach and Shavuot, a decree was promulgated to gather up the inhabitants of Mlynov/Mervits in one ghetto. The ghetto was set up and the [plan] carried out. In two narrow and small streets, all the inhabitants of the two townlets were gathered and from the surrounding villages. 10-12 persons — and sometimes more — were crowded together in every room, barbed wire fence was set up, with no entrance or opening, the trap around us was set. (Asher Teitelman, "Massive Disaster," original p. 40 original, English p. 36)

Asher's father, Nahum, added some additional detail.

Before Shavuos [the Festival of Weeks, which began the eve of May 21, 1942] when the German Kommandant Schneider left for a month's furlough to Germany, the Ukrainian Commander Navosad and community official Sovitski created the ghetto. The second day of Shavuos, [May 23] all Jews from Mlynov, Mervits, and from the surrounding villages had to leave their houses and move into the inner street. 5-6 large families, and more smaller families, were put in one house. We were fenced in with thick barbed wire. Standing at the gates were Ukrainian soldiers.[3] (N. Teitelman, “Depths of Hell,” original p. 320, English p. 304)

Survivor Saul Halperin identified July 10th, 1941 as the date the ghetto was fenced in with barbed wire. He wrote, "We lived in fear. No eating and no drinking. Like for Pharoah, we labored hard. The 10th of July 1941, the shtetl was fenced in with barbed wire. The Jews were driven from the surrounding area to Mlynov. The ghetto had been created. The Ukrainian police guarded us day and night. The number of illnesses multiplied; people died of hunger, need, and fear. Bodies were swollen from hunger."

***

The Nazis Loot Jewish Posessions

Bunia Steinberg, who lived in Mervits, recalled that "The first or second day of Shavuot (I don't remember which), we were ordered to go straight to the ghetto in Mlynov." Before going into the ghetto, Bunia, her mother and her sister-in-laws sewed gold coins in their clothing; these coins were critical to the families at a later period when they were looking for places to hide in the homes of Jews.

In the entrance to ghetto, the Nazis searched the belongings of the Jews and looted many things they brought with them: potatoes, oil, flour, and clothing. A search was also carried out on my mother and when they wanted to search her belongings, she resisted. Luckily for her, Hungarian soldiers were the ones who searched her.[4] They left her alone and she was able to bring all her belongings into the ghetto. [Shoshana Baruch, A Struggle to Survive, Heb. p 28, English p. 27]

***

Descriptions of the Ghetto

Survivor Sura (Sarah) Shichman (a niece of both Sonia and Rokhl Teitelman) was one of seven children and the only survivor in her immediate family. She recalled that

In May 1942, the Germans chose the smallest and dirtiest street, encircled it with wire, and made the Jewish ghetto inside. If the Nazis allowed a Jew to bring a few things into the ghetto, they did not allow any food whatsoever inside. Hunger started immediately. I still see small, hungry children in front of my eyes." (See Sore Shichman-Vinokur "Nazi Crimes in the Volyn Neighborhood," original p. 449, English p. 431)

Yehudit recalled the Mlynov ghetto

was confined to two streets, Shkolna and Dubinska. Permission was given to Jews from the other streets to bring personal belongings with them. Those evacuated individuals entered the homes of residents of the two streets just mentioned. Most made personal arrangements [which houses to join] and for others, the Judenrat organized the operation. Due to overcrowding, sanitary conditions worsened. In our living quarters — of two rooms — our aunt also lived and the family of Grandmother with two grandchildren (The kids of Yenta had been killed already at the beginning of the occupation). In general, the density reached 7–8 people per room. The ghetto was surrounded by a barbed wire fence and had two gates guarded by Ukrainian police. The Jewish police generally accompanied those who went out for work. Apart from those who left for work in groups, no one was permitted to leave the ghetto. (See Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 290, English p. 272).

Sonia and Mendel, who also lived in Mervits, recalled that just before the Festival of Weeks (Shavuos) in May 1942:

an order suddenly came that the Jews from Mervits and from the surrounding area, meaning from the villages, should all move to Mlynov. Starting in Shul Street until Kisil Yoel's, and until the synagogue near the puddle, the area was fenced off with a heavy barbed wire and isolated from the general population. Only two gates would allow Jews to be taken out for labor.

A decent pen cannot in any way describe how the Jews from all the other Mlynov houses had to press themselves together like herrings in houses that had been already emptied of furniture, bedding, and household things; this tragedy I cannot describe in any way.

I was present when my sick brother Yankev-Yoysef, of blessed memory, with his family, and my old uncle Khayim-Mayer of blessed memory, with his children and families, and my uncle Yankev Gruber, of blessed memory, with his wife, and more people, were forced into the ghetto. Nobody in the world could picture such things.

In front of our eyes, we could see the beautiful days of May in Europe, with their full beauty, where both nature and humanity live and laugh. From the big light our darkness increased. In the ghetto, the decrees became harsher. The news coming from every neighborhood was bad. And just like the Mlynov kehilla was united with all the surrounding shtetlekh, so it was with the ghettos. (Sonia and Mendel, "Tragic Tales," original p. 331, English, p. 313).

***

Efforts to Work Outside the Ghetto

As soon as everyone was in the ghetto, Yehudit Mandelkern remembered the "general feeling was that one should do whatever possible to be outside the ghetto." Those who worked on

agricultural farms were subjects of envy by the ghetto residents. My sister, Fania, worked in a German office for road work and had a work certificate. The German soldiers who were in charge of this office were Austrian and treated her fairly well. Every evening she returned to the ghetto. While at work, she connected with a Polish family by the name of Veitschork from whom she got food. She also initiated a discussion with them about hiding in the event of the ghetto liquidation. The head of this family was a sentry for the roads. (See Mandelkern Rudolf, "Life Under...," original p. 290, English p. 272)

Bunia's experience working outside the ghetto allowed her to barter and bring back necessities into the ghetto. But her experience was much more difficult. She worked initially in a four shop in Mlynov until the workers were asked who spoke German. When Bunia indicated she could speak the language, she was transferred to a military hospital in town. Her daughter recorded her mother's memories of that time.

My mother worked there [in the military hospital] cleaning and sustained beatings by her superiors. Periodically, she was ordered to polish the German officers’ boots. One of them was not happy with the work, and she was lashed with a whip so that she would improve. The harder my mother tried to polish the boots, the officer [nonetheless] remained dissatisfied and continued to beat her. There were also some officers who treated her nicely. Periodically, when there was a need to translate from German to Ukrainian, she was called upon to translate. After 6 weeks, the hospital moved to another location...(Baruch, Struggle To Survive," original p. 25, English p. 26)

Icek Kozak was given a position as a driver for the Germans.

The summer [of 1942] passed and outside it became cool. The Judenrat sent for me and said that the Germans needed a driver, so they confirmed that I would do it. I drove the Germans wherever they needed to go....

I continued to drive Germans with horses and wagons... The German whom I drove around thought I was a Russian. He assigned non-Jews to work in Germany.... One time I was with my German at a Czech's in Novyny. When I needed to give the horses a drink it was raining, so I put on my jacket. I forgot that my two yellow patches were sewed on it, and the German saw this through his window. He called me in and asked about it, so I answered in Ukrainian that the day before I had killed a Jew, and I had taken his jacket. The Czech translated my words into German, and my excuse was accepted.

Now my real troubles began. All the Jews were in the ghetto while I drove around with my German. Every day I would come home and tell all the latest sad news: here the shtetl was destroyed, and there another shtetl was liquidated. I used to go to Christians that I knew, and I begged them to allow me to hide there. (Icek Kozak, "What My Family Endured" original p. 355, English p. 331)

Miriam Blinder, who was 13 when the War began, went to work for a farmer:

In our house our big troubles started earlier than everywhere else, because my father had been taken right away. Unfortunately, he did not return. My mother had to become the breadwinner for the whole family. The bread rations were then 90 grams of bread a day, and even children had to go to work...

I, therefore, looked for a way to help the family with some food. I went to work for a farmer with the name Grabavetski. The work was difficult, but I was glad because the farmer helped me to feed my house somewhat. When I used to bring home the little bit of food, it was a holiday in the house. My mother always waited for me and used to always go to the ghetto fence to be able to see me from a distance. (See Miriam Blinder, "Where Do We Go?," original p. 370, English p. 342)

***

Underground Resistance

Once the ghetto was created, everyone knew what the future held. As Yehudit Mandelkern recalled,

Immediately following the establishment of the ghetto, the feeling prevailed that this was the prelude to the general liquidation. A number of youth, among them my brother Moshe Mandelkern, the brothers Shlomo, Yaakov, and Yitzhak Nekunchinik, the police Zelig Zider, Tzvi Gering, Peretz Tesler and Shlomo Schechman; Rachel Liberman, Rivka Liberman, Liuba Chizik, Hannah Veiner, Zelig Pichniuk and others, tried organizing resistance.

At the head of the group was Avraham son of Ben-Tzion Holtzeker. Shlomo Nekunchinik who lived before the war in an isolated home outside of town, had connections with foresters who had weapons. One of the Polish foresters promised him to supply arms to the Jewish youth. The youth gathered money to purchase weapons and prepared kerosene to set fire to the ghetto when the liquidation was announced in order to create chaos and provide an opportunity to flee. The group secured two rifles, that were held by Avraham Holtzeker. It was agreed that if escape to the forest was successful, those fleeing would try to reach the forests of Polesia and the groups ofpartisans, whose existence had already been initially rumored.