-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

.

***

BIOGRAPHIES OF THE AUTHORS

Bring the essays of the Memorial book alive by understanding the background of those authors who wrote them. The writers remember the shtetls and their lives there at different moments of time between 1890 and 1945. While many of their essays recall later tragedies, many also recall enjoyable nostalgic memories from childhood from earlier periods and from before the end.

***

Alphabetical Listing by Surname:

| B | Sylvia Barditch-Goldberg | Israel ("Sol") Berger | F | David Fishman | Moishe Fishman | G | A. [Eliyahu] Gelman | George (Gershon Joe) Goldberg | H | Lipa Halperin | Aaron Harari (née Berger) | Yankev (Yankel) Holtzeker | I | Moshe Iskiewicz (Isakovich) | J | Shirley Jacobs (née Barditch) | L | Yitzhak Lamdan | Helen Lederer (née Gelberg) | Yosef Litvak | M | Boruch Meren | S | S. M. T. (pen Name for Sonia and Mendel Teiteilman) | T | Moshe Tamari (Teitelman) | Asher Teitelman | Sonia and Mendel Teitelman | V | Sunny Veiner (or Weiner)

***

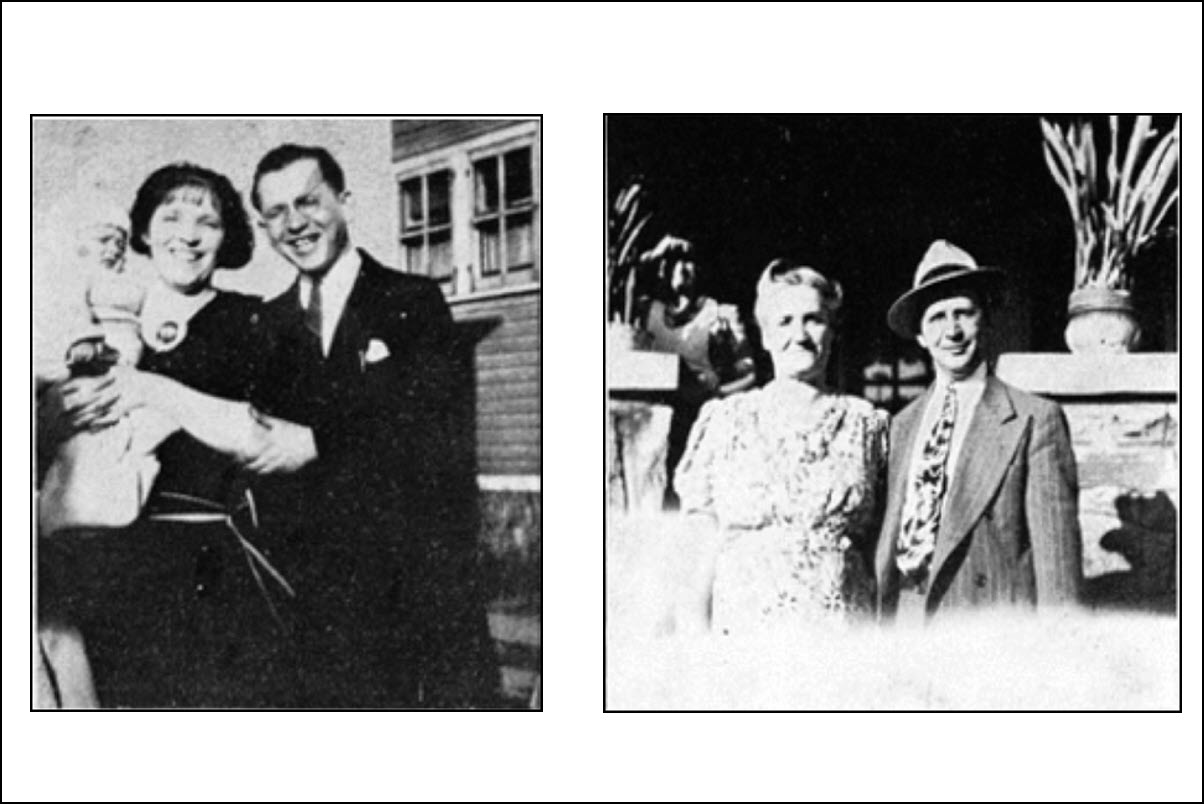

Sylvia Barditch–Goldberg, Jackson Heights, [Queens, New York]

Sylvia Barditch–Goldberg was the only woman on the Book Committee of Eight responsible for bringing out the Memorial Book. She was born Silka Borodacz in the town of Lutzk, one of five children. But she always had a softspot in her heart for Mlynov, which is where her grandparents Itcik and Malia Ferteybaum lived. Sylvia would visit her grandparents in Mlynov on holidays and during summer vacation and she wrote about her sweet memories of those times in her essays in this volume.

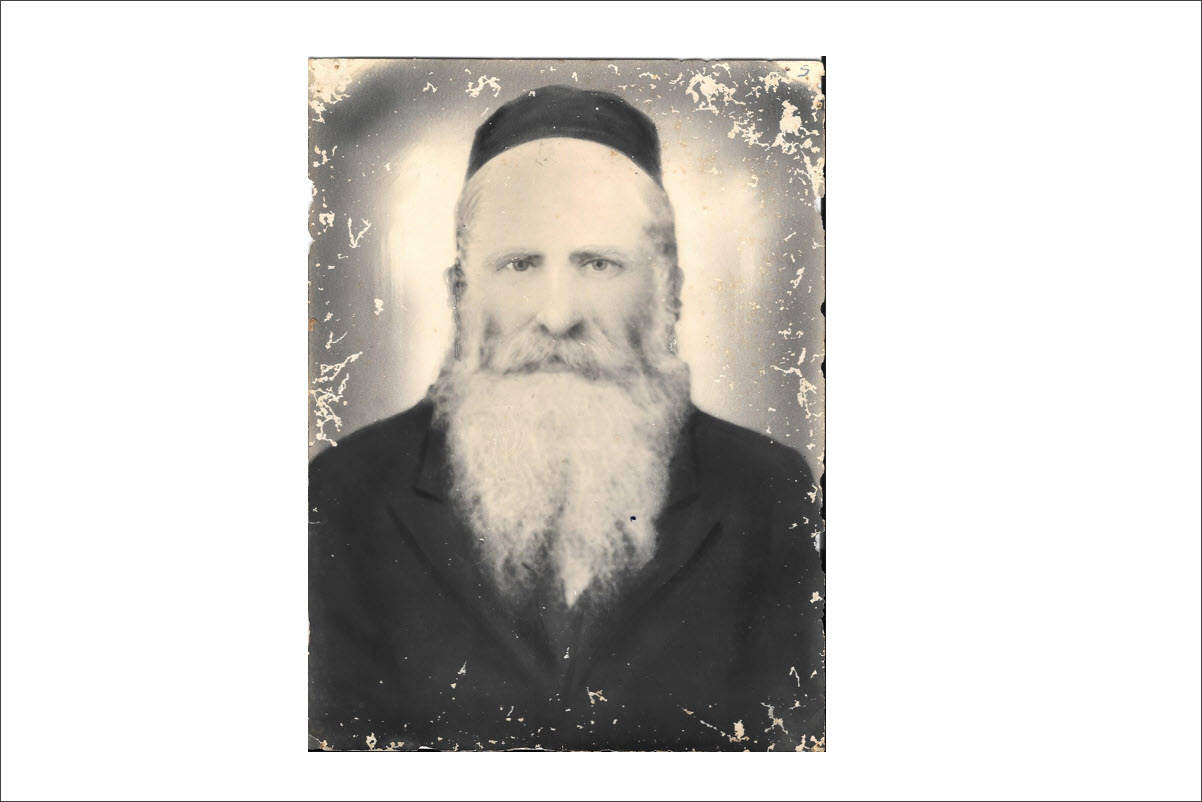

In one of her essays, Sylvia recalls that her grandfather Icik was called “Starosta," a slavic term suggesting he had a leadership role in a range of civic or administrative duties. Sylvia recalls that he was dedicated to the Stoliner rebbe and offers a portrait of him and his religiosity and a window into the practices of the Stoliner Hasidim in Mlynov.

Sylvia's mother, Bassa (1876–1960), was very probably born in in Mlynov like her brother, Usher, despite her contradicting records.[1] In any case, Bassa married Yehiel Borodocz from Lutsk. Theirs was not the only marriage between a young man from Lutsk and young girl from Mlynov. Mollie Demb from the large Demb family in Mlynov, for example, married Samuel Roskes from Lutsk. And in one of the essays Sylvia wrote, she recalls herself as a young girl attending a wedding between the daughter of the Mlynov blacksmith and a young man from Lutsk.

Yehiel and Bassa had five children in Lutsk: Paul "Peretz" (1895–1961), Sylvia "Silke" (1902–1984), Sura (later Shirley Jacobs) (1905–1983), Meyer (1907–1922), and Benjamin (1908–1979).

The Borodocz family immigrated to the US where their surname became Barditch. Sylvia’s father, “Jehiel Borodocz” (Isidore Barditch), arrived in 1910 and was joined in 1911 in Baltimore by her uncle (her mother's brother), “Usher” Ferteybaum, where his name became Harry Tatelbaum. Usher was born in Mlynov and had traveled to Baltimore with two other Mlynov men, Israel Schwartz, and Nathan (Hyman) Fischman, both of whom brought families to Baltimore.

WWI intervened before Sylvia's father could bring the rest of the family to America. Sylvia was not reunited with her father until October 1921, when she traveled with her paternal grandmother and several of her siblings from Le Havre France to Baltimore. Her mother and younger brother were delayed and followed a few weeks later. The family settled in Baltimore, but after a tragic hit and run accident that killed her younger brother Meyer, the family felt the need to leave Baltimore behind and they moved to New York. There Sylvia married Joe (Gershon) Goldberg from the Mlynov Gelberg/Goldberg line.

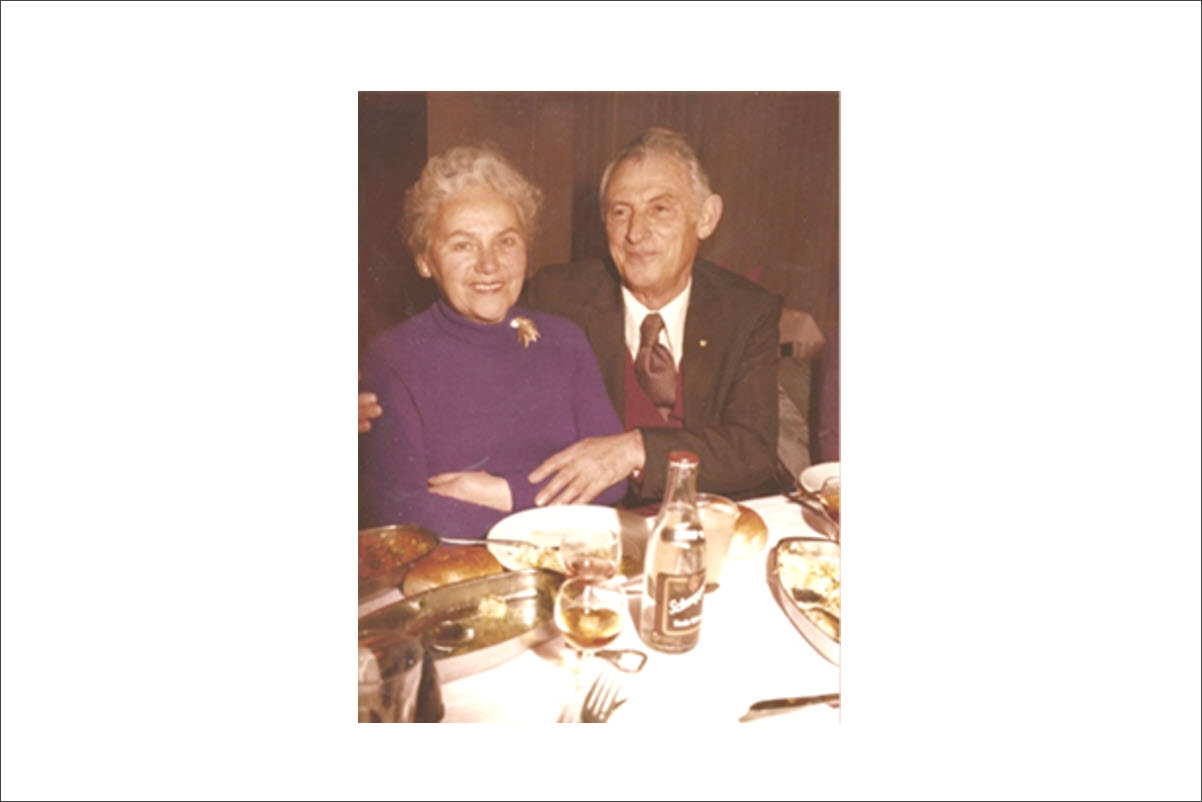

Sylvia was remembered by those who knew her as a dynamo, always typing at her Yiddish typewriter, which is probably where she typed the essays in the Mlynov Memorial volume. Photos of her (see below) indicate just how stylish she could be and suggest continuity between the young girl who remembered dressing up for a Mlynov wedding and the later adult she became.

***

Additional Reading

Read about The Mystery of Sylvia Goldberg or about the Goldberg Family from Mlynov. Sylvia's sister, Shirley (Barditch) Jacobs also contributed an essay to this volume.

Essays By Sylvia Barditch-Goldberg

"A Wedding in Mlynov," (Yiddish), 27–29.

In this evocative essay of an early childhood memory, Sylvia recounts going as a very young girl to visit her grandparents in Mlynov annually on the festival of Shavuot. During one of those visits, she participated in a memorable wedding that was to leave an indelible impression for the rest of her life. The occasion was the wedding of the Mlynov blacksmith's daughter with a young man from Lutsk. It was an important event that brought the whole town together. Even the Count sent a "carriage with two pairs of horses decorated with ribbons and bells, to bring over the bridegroom with his parents." The Count did so "for all important people who married off their girls." Sylvia recalls dressing up special for the event and becoming the center of attention that day. Her account is rich with tactile details about the scene: the klezmer music, the deaf fiddler who makes the crowd weep, and her grandfather with his long kapote dancing in a circle. One can almost feel as if one were there that day with Sylvia and understand why the day impressed itself on her childhood memory.

"Stoliner Hasidism in Mlynov," (Yiddish), 80–82.

Sylvia here recalls her grandfather, Itcik or Yitskhok "Staroste," who was a dedicated Stoliner-Karliner hasid. By Sylvia's account, "a handsome, erudite Jew, and an expert in music, he was one of the distinguished members of the community in the last century in Mlynov. He was also known and respected in the surrounding areas." Sylvia describes how her grandfather would go to the Rebbe on the holidays and convinced her father (his son-in-law) to become a Stoliner as well.

"Visiting My Grandparents," (Yiddish), 266–271.

A charming essay about Sylvia's visit to her grandparents in Mlynov during a summer vacation at a young age. She is sent alone by wagon, with a driver from Mlynov who also transported other travelers. Describing a stop at an inn along the way, and then her experiences being greeted by other Mlynov families upon arrival, and learning to milk the cows at her grandparents, this essay shows how a big city girl looked forward to and experienced the Mlynov shtetl as the beautiful countryside and how she enjoyed all the attention she received in the small town.

Notes

[1] Sylvia's mother's brother, Usher (Harry Tatelbaum) lists his birthplace as Mlynov on his passenger manifest in 1911. He arrived in Baltimore with two other Mlynov men. Since her brother was born in Mlynov, and her parents lived there, I suspect that Sylvia's mother also was born there. Her later US records, however, are inconsistent. When she arrived in 1921 her passenger manifest says she was born in Varsovic (perhaps Varkovychi) and her Petition says she was born in Lutsk. ↩

***

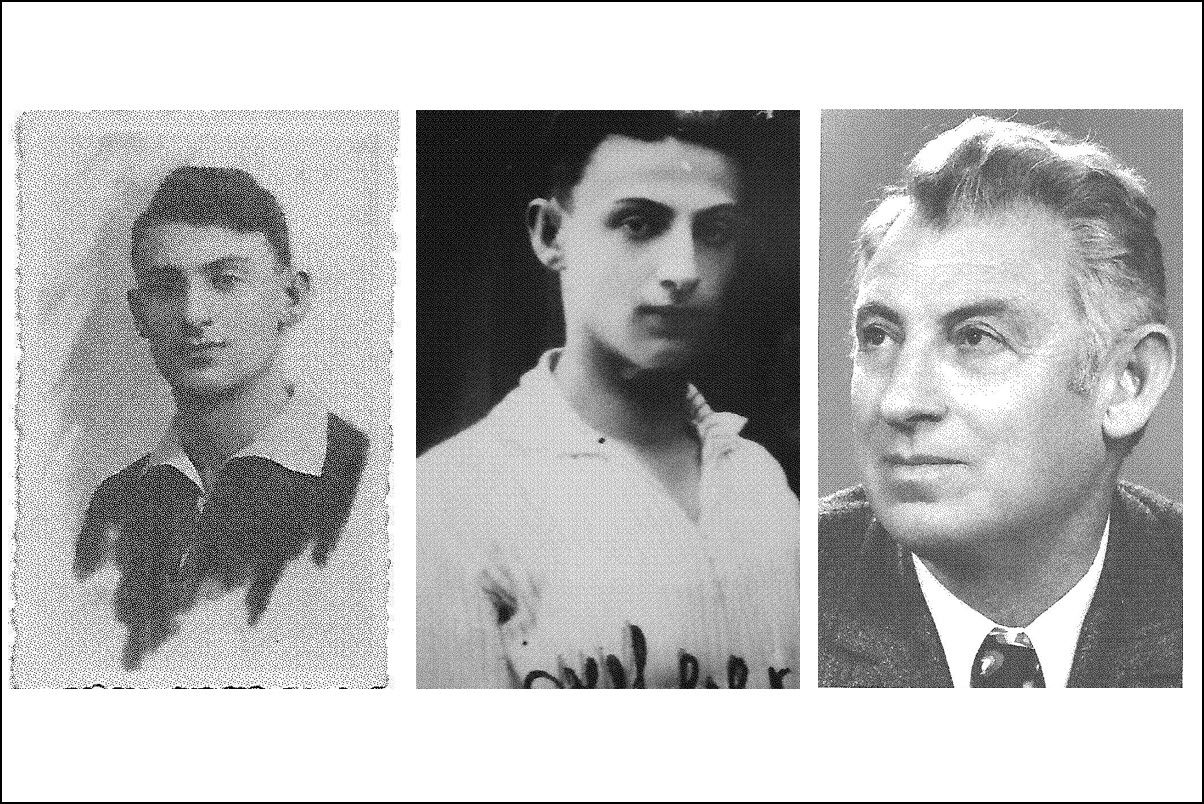

Israel "Sol" Berger, Chicago

Israel ("Sol") Berger was born in Mlynov in 1898, the son of Wolf Berger and Golda (Kentor/Kantor). Yisrael (shorted to Sol in the US) (1898–1977) was the oldest of six children and the first in his immediate family to immigrate to the States. His youngest brother, Aaron (Berger) Harari, was on the Book Committee for the Memorial book and a contributor of several essays and photos to this volume.

In 1914, at the age of 17, Sol followed some of his Berger first cousins to Chicago and arrived in July, shortly before WWI broke out. In 1926, Sol was joined in Chicago by his brother Karl (Kalman) Berger (1906–1990) joined the other Mlynov boys in Buenos Aires and eventually get into the US under the assumed name of Abraham Machlin.

Two of Sol's youngest siblings made aliyah. Rosa Berger (later Rosa Chizik or Tzizik) arrived in Palestine in 1933, and Aaron (Berger) Harari, her older brother, made aliyah in 1934. Aaron was a leader in reviving the Zionist youth movement, Hashomer Hatzair, in Mlynov in the 1920s.

Sol’s sister, Hannah, and his parents, were killed in the liquidation of the Mlynov ghetto. Their other brother, Shaul (Saul), was conscripted or enlisted in the Red Army and later married and settled down in Russia. In Chicago, Sol married Dynka Selkoff and they had two sons, Bernard and Nathan Zane Berger.

Additional Reading Read more about the Mlynov Berger family saga.

Essay by Sol Berger

"Shtetele Mlynov," (Yiddish), 63–64.

In this essay, Sol shares very tangible and tactile memories of childhood in Mlynov from before his immigration to Chicago in 1914. His memories are presented as a beautiful stream of consciousness in which scenes from childhood are passing before his eyes and include memories of activities with friends, practices of the Hasidim in prayer, the mud, the water carrier, the visits to the bathhouse, among others.

***

David Fishman, Baltimore

David “Dudek” Fishman, born in Mervits in 1899, was the eldest of three children of Moishe Fishman (1873–1968) and Chaya Gilden (1880–1927). His younger brother, Berel (Ben) Fishman, left for Baltimore in 1920 with the first group of families to leave after WWI. The rest of the Fishmans made a significant stir in Mlynov in 1921 being the first family to make aliyah to Palestine, a story told by Boruch Meren, another contributor to this volume.

David's father, Moishe Fishman, also a contributor to this volume, became an ardent Zionist under the influence of his boss who was a construction contractor. In Palestine, the Fishman family became founding members of Moshav Balfouria, named for Arthur Balfour and the Balfour Declaration.

In 1924, David was joined in Palestine by his Mlynov sweetheart and first cousin, Eta Goldseker. The two of them were married in July of that year. Eta and David had their first daughter, Shimonette Anna (Selma Ann), in Palestine in 1926. Life in Palestine was arduous and dangerous at the time, and in 1927 they made the difficult decision to leave Palestine and settle in Baltimore where David's brother and several of Eta's siblings had settled. They were not alone in this decision. That was one of the years when the emigration from Palestine was greater than the number of inbound immigrants making aliyah. David and Eta's, second daughter, Irene Siegel, was born in Baltimore in 1929. Irene became a family historian and preserved a great number of photos and stories about Mlynov and the town's inhabitants.

Essays by David Fishman

"There Was Once a Shtetl Mlynov," (Yiddish), 65.

Both mournful over what has been lost but evocative with childhood recollections, this short essay recalls some of David's memories before his aliyah. David, for example, writes:

"The pine tree forest, once the scene of the youth of Mlynov and Mervits, alive with songs and discussions and also love, is no longer there. And don’t forget the weeping willow trees which provided the branches used during the Sukkot prayer service. Also remember the Mlynov shopkeeper with his fire pot, who used to sit, worried and waiting, for a good Christian customer. Remember the Mlynov market with its passengers going to Dubne (across from Brukhe-Batya’s store). I am reminded now of the busy market fairs."

"In the Shtetl," (Yiddish), 65.

A short series of tactile memories of the place from David's childhood, including some of their childhood fears and tales.

Additional reading: You can also read more about the Fishman family and the family's decision to make aliyah

***

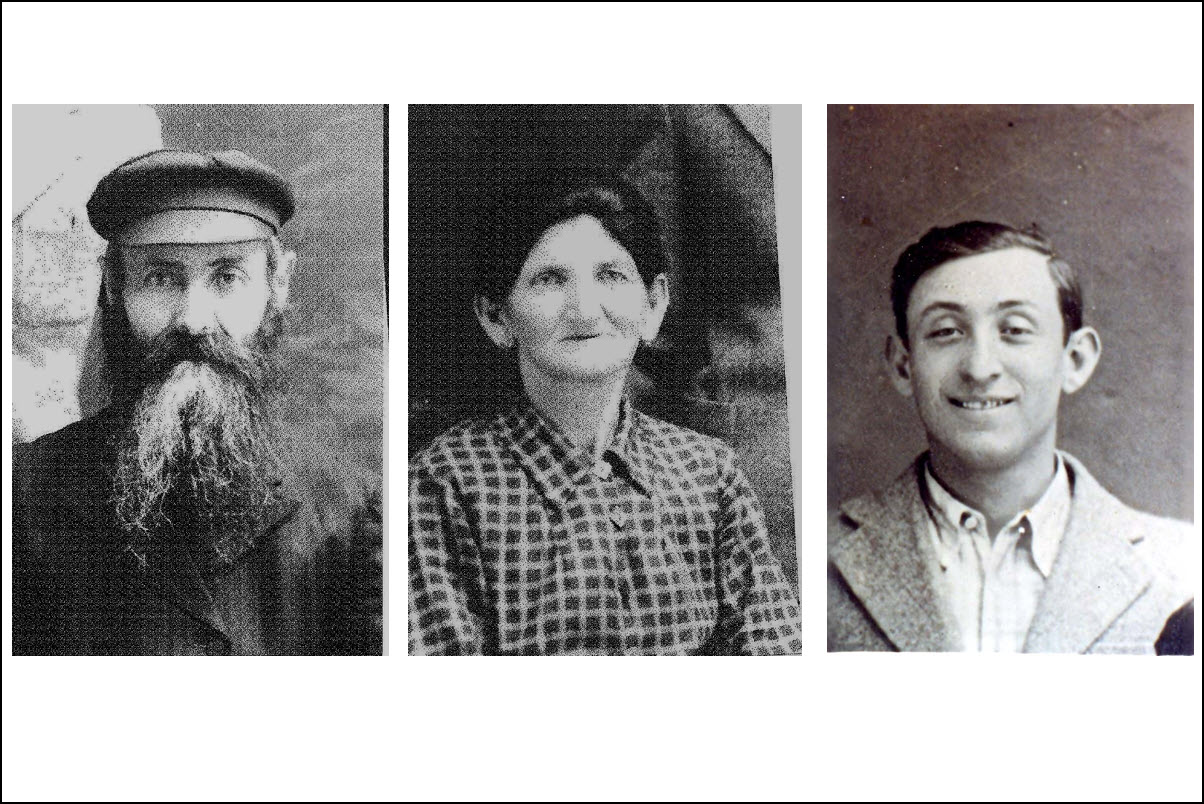

Moishe Fishman, (Balfouria)

Moishe Fishman (1873–1968) was the son of Berel Dov (also Dov Aryieh) and Toba Fishman. He was born in Mlynov but worked for twenty-five years in a small town of Sloboda, which on old maps was in an area now within current day Uzhynets', Ukraine, which is only 6 km (3.5 m) from Mlynov. He married Chaya (Gilden) before 1899 when his eldest son, David (1902–1993) was born, one of the other contributors to this volume. Moishe and Chaya had two other children, Berel (Benjamin) (1902–1993), and Chuva (1905–1971). Moishe Fishman (1873–1968) was the son of Berel Dov (also Dov Aryieh) and Toba Fishman. He was born in Mlynov but worked for twenty-five years in a small town of Sloboda, which on old maps was in an area now within current day Uzhynets', Ukraine, which is only 6 km (3.5 m) from Mlynov. He married Chaya (Gilden) before 1899 when his eldest son, David (1902–1993) was born, one of the other contributors to this volume. Moishe and Chaya had two other children, Berel (Benjamin) (1902–1993), and Chuva (1905–1971).

After WWI, their son Berel joined three other Mlynov families heading to Baltimore, where he settled and soon married Clara (Shulman) also from Mlynov, who arrived in 1921 with her family.

Moishe, for his part, had by this time become an ardent Zionist under the influence of his boss with whom he did construction. In 1921, Moishe shocked the residents of Mlynov by the decision to make aliyah, in a story told by Boruch Meren in this volume. With his wife, Chaya, and two of his children, David and Chuva, the family made aliyah to Palestine where they eventually settled in Balfouria. They were the first Mlynov family to make aliyah.

Moishe remained in Balfournia despite the hardships of the early years in Palestine and even though his son David would leave Palestine and make their way to Baltimore. In 1938 after his own aliyah, Boruch Meren sought out Moishe Fishman on the Moshav and recorded their conversation together that day.

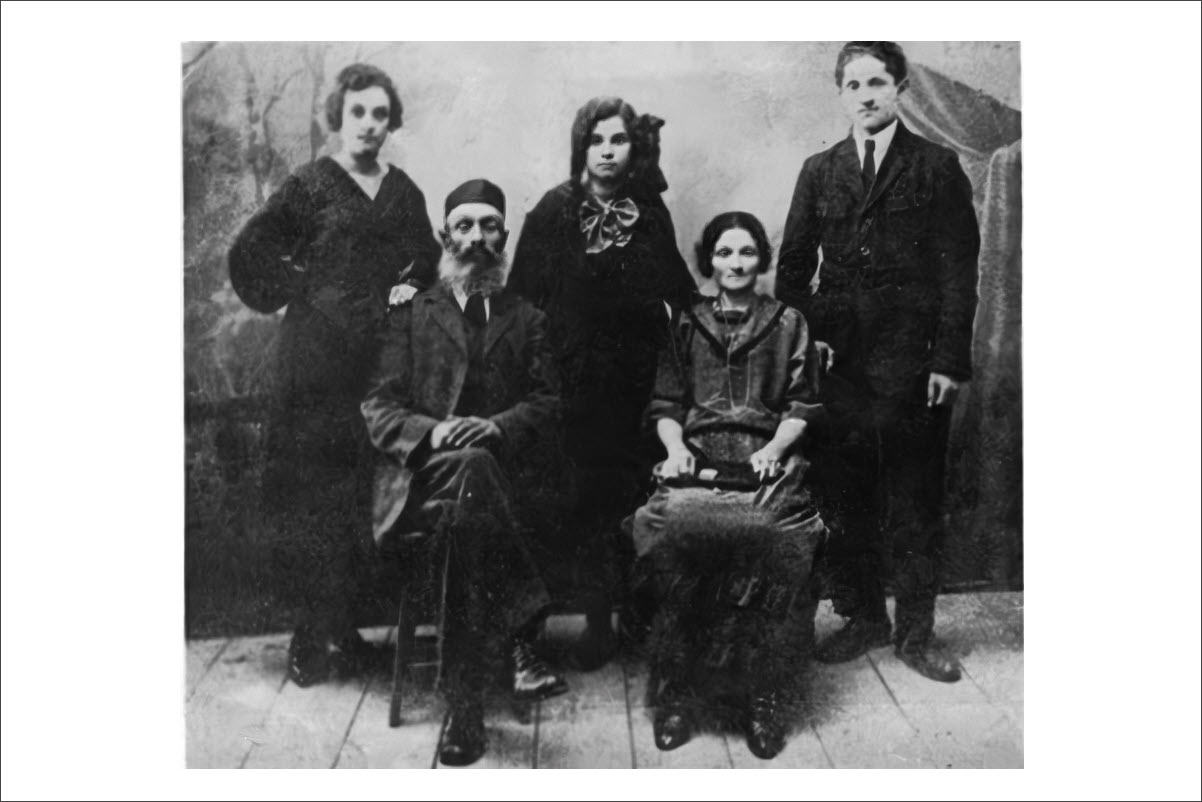

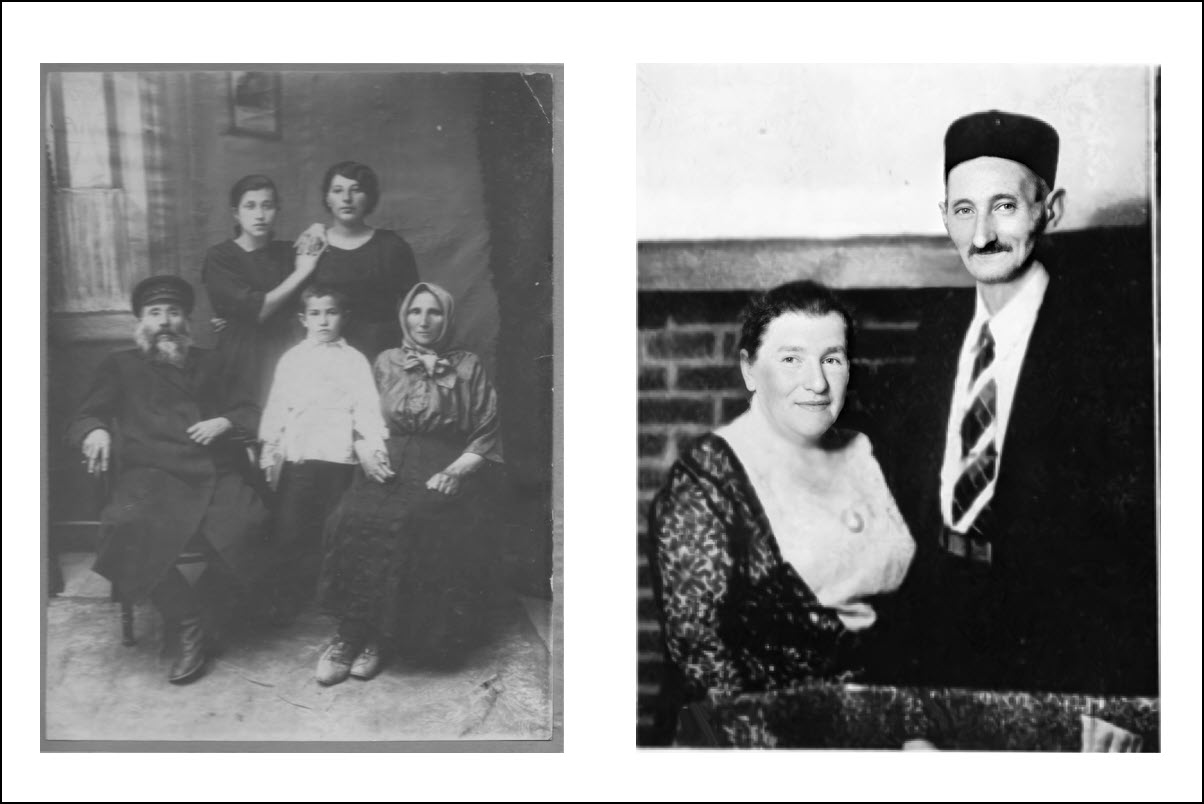

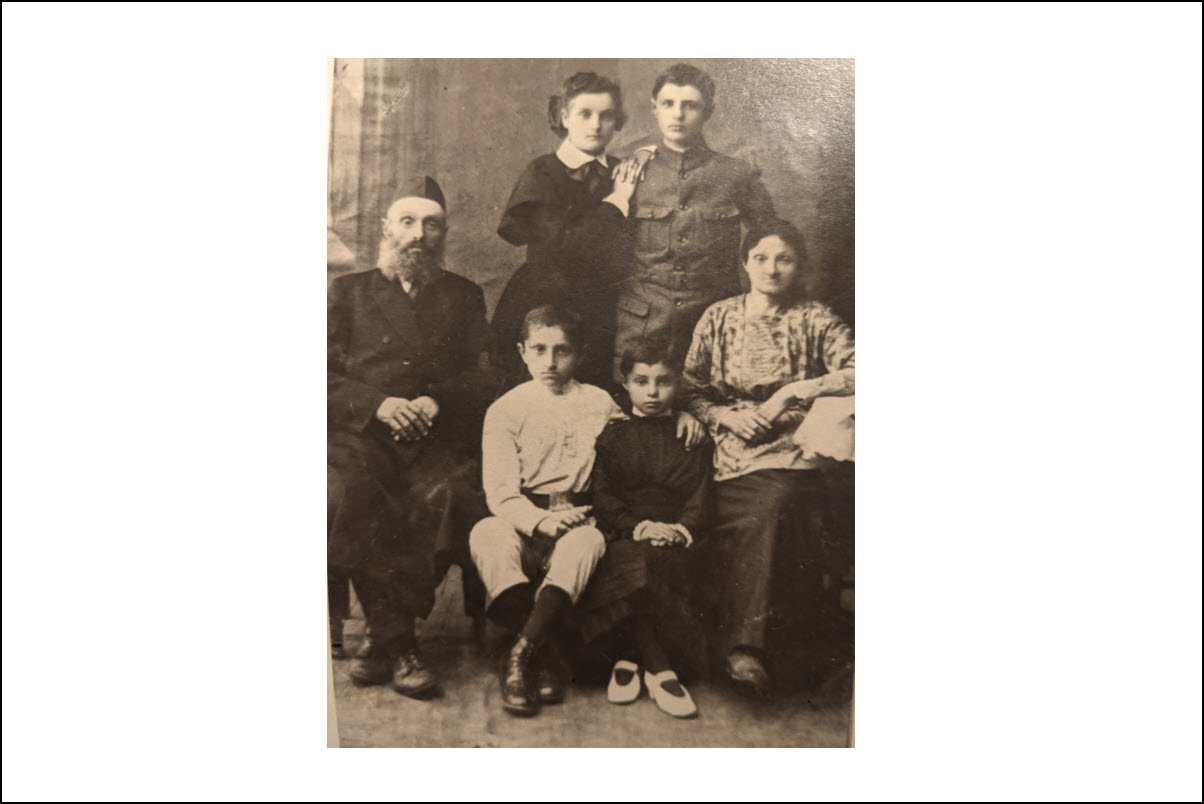

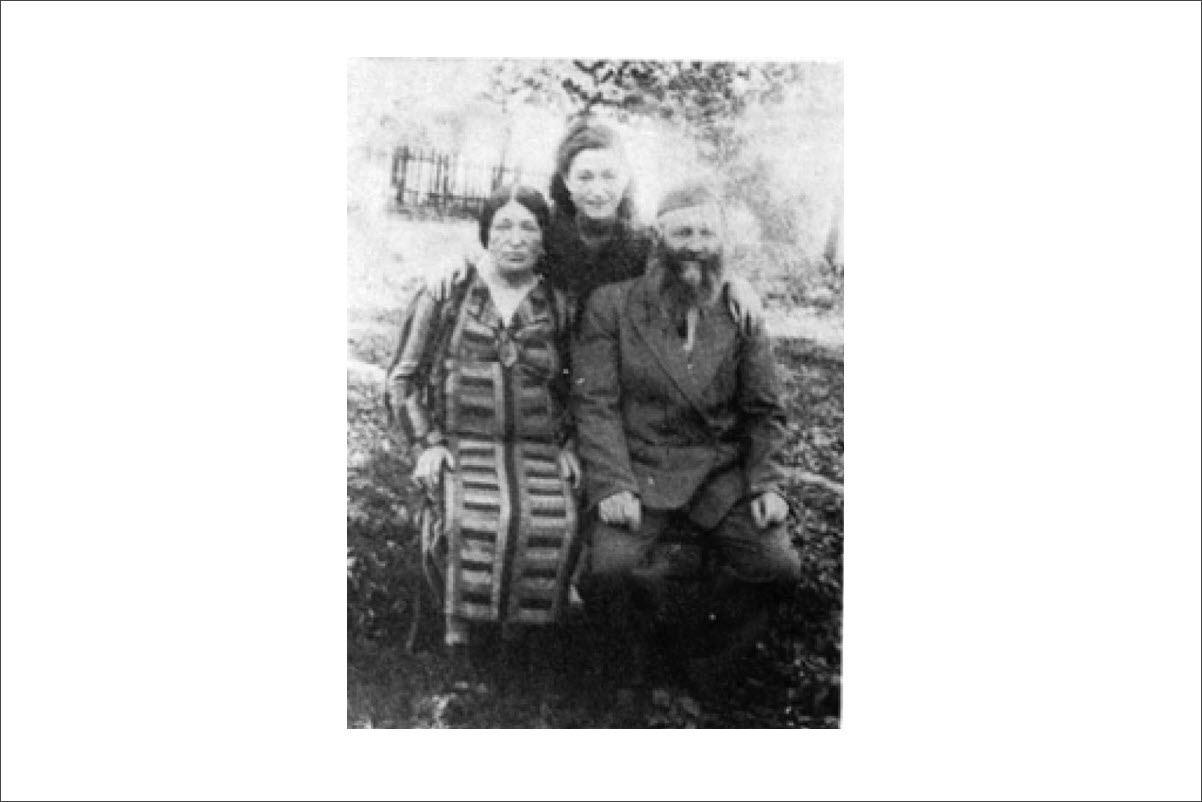

Moishe Fishman with family and other Mlynovers in Moshav Balfouria.[2] Courtesy of Irene Siegel.

Moishe Fishman with family and other Mlynovers in Moshav Balfouria.[2] Courtesy of Irene Siegel.Essay by Moishe Fishman

"Mlynov in the Past," (Hebrew), 60–62.

Moishe recalls his life in Mlynov before WWI through his first decade after his aliyah. His stream of consciousness includes the story of how the Goldsekers came to Mlynov, the local memorial and eternal light for the Stolin Rebbe who died in Mlynov, the pandemic of 1894/1895, the synagogues, the flour mills and fires that burned them down. Also included are several memories of his decision to make aliyah and his early ears in Palestine during the 1920s.

Additional Reading

Read about how Moishe's decision to make aliyah created a stir in Mlynov as told by Boruch Meren. Or read more about the Fishman family.

Notes

[2] 1956. Seated (right to left) Chuva (Moishe's daughter), Moishe with black cap, his son Benjamin visiting from Baltimore, Malkah (Lamdan) Mandelkern (Mandelkorn); Backrow (left to right) Mollie (Demb) Roskes (made aliyah from Baltimore), Shmuel Mandelkern (Mandelkorn), Michel Slivka (son-in-law), Chayuta (granddaughter), Aharon (grandson). ↩

***

A [Eliyahu] Gelman, (Netanya)

Eliyahu Gelman (1913–2008), born in Mervits, was the son of Pesach Gelman and Raisi/ Raisel (surname?) and had four sisters, Esther, Yenti, Freidel and Dobrish. He made aliyah in 1938 and he married Yehudit Rhyber (or Reiber) (1922–2000) from Berestechko in 1944 and had three children.

In an essay in this volume, Eliyahu indicates that his family fled Mervits during WWI to the town of Varkovychi, 32 km east, which was not destroyed the way Mervits was. The families of his father's two brothers, Joseph and Moshe, joined them there. His father taught Humash (Bible), Gemara and Rashi there. In the list of martyrs, Eliyahu's father is described as a shochet (kosher slaughterer) and scribe for torah, phylacteries and mezuzot, and was himself called the son of Itzi, the shochet.

It seems likely that Eliyahu was descended from the Gelman family described in household 102 in 1858 revision for Mervits. As discussed there, the couple Abram Gelman and his wife Haya-Gitlya match the names of ancestors remembered by Eliyahu's daughter, Rachel Gordon. The man named Abram in this revision is himself the son of a man name Pesaych who was likely the namesake for Eliyahu's father.

After the end of WWI, Eliyahu's sister, Esther, married a cousin and returned to Mervits to live. Eliyahu's father managed to send two older daughters to America. In 1928, Eliyahu's father, Pesach, and the rest of the family returned to Mervits. His father, now 70 years old, felt his days were numbered and he wanted to be buried with his parents and ancestors. Pesach passed away soon thereafter in a dramatic scene that Eliyahu describes in his essay.

Eliyahu, his mother and other sister, lived for a time with an aunt who had a convenience shop in a nearby village. Eliyahu made aliyah in 1938.

Most members of Joseph and Moshe's families (his father's brothers), perished in the Varkovychi ghetto. A son of Moshe Gelman, Meir Gelman, survived and made it to Israel. His aunt Belumah and her family also survived.

There are three other Gelman families mentioned in the Mlynov Memorial book who probably were siblings or cousins of Eliyahu’s father. There is a photo (p. 477) of Tola Gelman and his three daughters. They are not included in the martyr list so it is uncertain what became of them. Next to a photo of Tola’s daughters is a photo of Joseph Gelman and Riko or Rikel (Gruber). Justaposition of photos in the Memorial book often suggests familial relations. Gedaliah (Joseph) Gelman (1876–1951) and his wife Riko/Rikel (Gruber) (1881–1952) migrated to the US where they took the surname Alman and settled in Springfield, MA. Joseph arrived first in 1913, and Riko followed in 1921.

The list of martyrs and Yad Vashem records also mention an Avraham Gelman (1880–1942) who was married to Mahla or Mahlia (1880–1942), daughter of R. Reuven and Nehama from Ostrog (Ostroh, Ukraine today). Mahla's maiden name was Klein. They had three daughters listed in the Yad Vashem records, Rakhel, Batia, and Nekhama. The Yad Vashem records were submitted in Hebrew by this Abraham's cousin, Batsheva Ben Eliyahu.

There was another Gelman family whose children had been born in Mlynov but who were living in Varkovitchi (Warkowicze) during the war. They were Iozek (Yosef) and Leah/ Lea (1880-1942), daughter of Moshe and Etil (unknown surname), and their children Fejga (Feiga) (1914–1942), Ester (1918–1942, Ester (1918–1942), Elia /Elijahu (1920–1942), Ephraim (1922–1942).

***

Essays by Eliyahu Gelman

"The Tree That Resembled a Menorah on the Way from Mervits to Mlynov," (Hebrew), 31–32.

In this essay, Eliyahu Gelman, writing from Netanya, recalls the legend of the Hasidic rabbi who died near Mlynov during a cold winter day while out trying to visit his Hasidim. It was snowing and about to become Shabbat. When he expired, his Hasidim planted a tree that grew into the shape of a Menorah. It seems likely that this legend refers to the death of the famous Hasidic rebbe, Rabbi Aharon Ben Asher from Karlin (also known as Rabbi Aaron II of Karlin) who reportedly died in Mlynov on a journey to the wedding of his granddaughter. He was the grandson of the original Rabbi Aaron the Great [Aaron ben Jacob Perlov of Karlin] (1736–1772), one of the early founders of the sect who helped the rapid spread of Hasidism in Eastern Europe, and was known for the fiery eloquence.

"Our Small Town Is No More," (Hebrew), 44–45.

Gelman reminisces on life after WWI including the intoxicating smell of lilac shrubs, the flowering of cherry, apple and plum trees and memories of Jewish festivals.

"The Two of Them" (Hebrew), p. 241.

Gelman recalls two enlightened men he knew who left home for bigger cities and subseqeuntly returned to their home towns. The first was Bentzi (Bentzion) Gruber who had literary aspirations and even caught the attention of Bialik. He returned home and became a grain trader.

The second was Hersch Leib Margulis. He left for Kiev to teach in a Russian school. There he was swept up in the Revolution initially and was appointed as a judge in the Socialist government. He also returned to his small home town.

Both men perished in the Shoah.

***

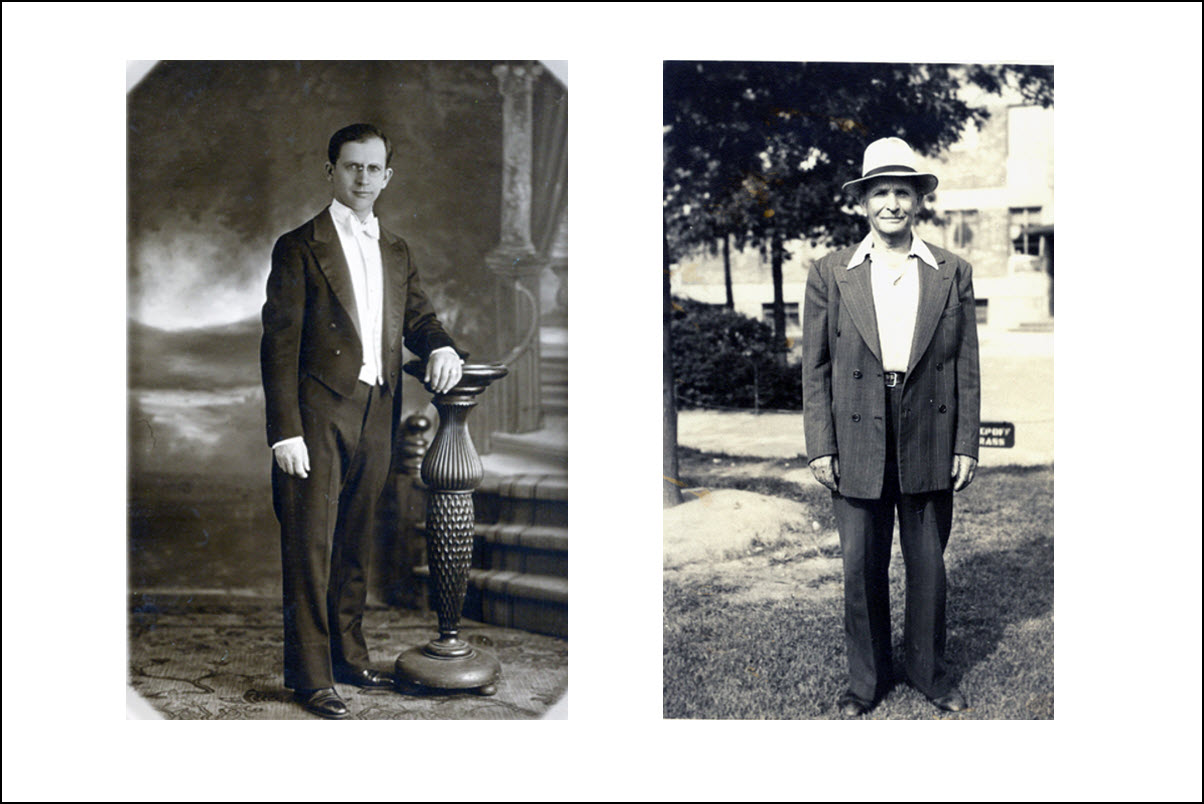

George (Gershon Joe) Goldberg, (Jackson Heights / Queens)

George "Joe" Goldberg (originally Gershon Gelberg) (1896–1984) was born in Mlynov the youngest of seven children of Labish Gelberg and Eta Leah (Schuchman). His second eldest brother Moishe (later Morris Goldberg) (1875–1967) headed to New York in 1911 followed by his sister Sura (1894–1941) who arrived in about 1912/1913 and married Samuel Spector. Gershon's two siblings were in New York when WWI broke out and Gershon was still with the family when it was evacuated from Mlynov, as recounted by his niece Helen Lederer in her contribution to this volume.

After the War, Gershon / Joe traveled to the US in April 1921 helping to bring his brother Moishe's wife and children to the US. It wasn't long before he married Sylvia Barditch, whom he probably already knew from her visits to Mlynov and who became one of this volume's organizers and a contributor of essays in her own right. George and Sylvia had one daughter, Edith (Goldberg) Kerker (1928–2009).

The families of his older brother Pinchus and his two sisters, Ester Malar and Chana Preziment, stayed in Europe. The only survivor was Ester's son, David Malar.

Essay By Gershon Joe Goldberg

"Our Former Way of Life in Mlynov," pp. 156-158.

Recalling life from Mlynov before he left in 1921, Gershon remembers the names of the friends who created the drama troupe and has vivid recollections of the corporal disciplinary techniques of the various teachers in cheder.

Additional reading:

You can read more about the Goldberg family saga.

***

Lipa Halperin, [Kibbutz] Yifat

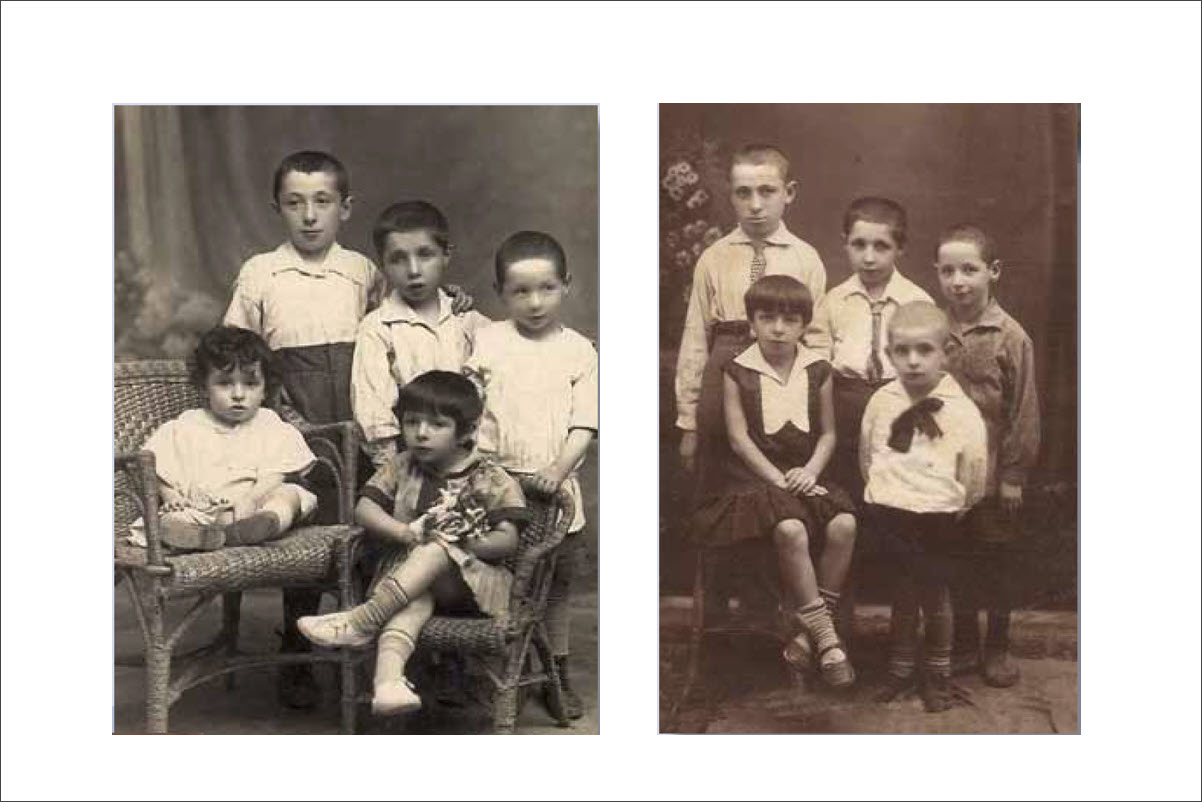

Lipa Halperin was one of the eight individuals on the Book Committee that pulled together the Memorial Book. He was born in Mlynov on March 29, 1907 and died on August 28, 1969 in Yifat, a kibbutz in the Galilee in northern Israel. He was one of five siblings, children of Israel Halperin and Rivkah Shrentzel (also spelled Shrenzel and Shrentsil). His mother's sister, Sorke, married a man from the Gertnich family in Mlynov, and photos show the Halperin and Gertnich cousins together in Mlynov.

Lipa was named after his grandfather, Lipa Halperin, who had married Pessia Hirsch from the large Hirsch family in Mlynov. A number of Pessia’s Hirsch siblings migrated to the US between 1910 and 1914. Lipa's family made a living in Mlynov from a small haberdashery which can be seen in the photo below and in the 1935 home movie taken by one of his cousins, A. D. Hirsch, during that visit back to Mlynov in 1935.

Lipa was involved in the Zionist Youth Group, Hashomer Hatzair, in Mlynov. When he was 26, in 1933, Lipa left Mlynov and joined a preparatory kibbutz (hachsharah) in Golina. He was older than most of the members by a number of years and promptly became one who had to care for all of them, seeking sources of financial support and advice in moments of crisis. After a year and a half, he was called to work in the center of “General Zionist Pioneer” (Hechalutz) in Warsaw, even though he was not a charismatic or organized man. The movement was seeking a man who could in fact strengthen the spirit of the members in the preparatory kibbutzim, which were beginning to disintegrate as the British government began restricting immigration. Lipa’s friends so appreciated his understated and consistent activities on the ground, that they refused, time after time, to guarantee him a certificate for immigration when he completedly his year of work. Finally, he was able to make aliyah to still Palestine in 1937.

In the late 1930s, Liba's siblings wrote letters to him in Hebrew from Mlynov, one of which is published in this Memorial volume. All of Liba's immediate Mlynov nuclear family were killed in the Shoah including his parents and four siblings.

In Palestine, Lipa married Tola Mack and together they had four children. The Halperin family settled in Kvutzat Hasharon (today, Ramat David) in 1940. In 1954, due to overcrowding with a neighboring kibbutz in Ramat David, the entire Kvutzat Hasharon moved to a nearby hill and built Kibbutz Yifat. Lipa’s son Yisrael, named after Lipa's father and born April 11, 1950, fell in battle as a fighter in a commando unit during the War of Attrition (June 11, 1970).

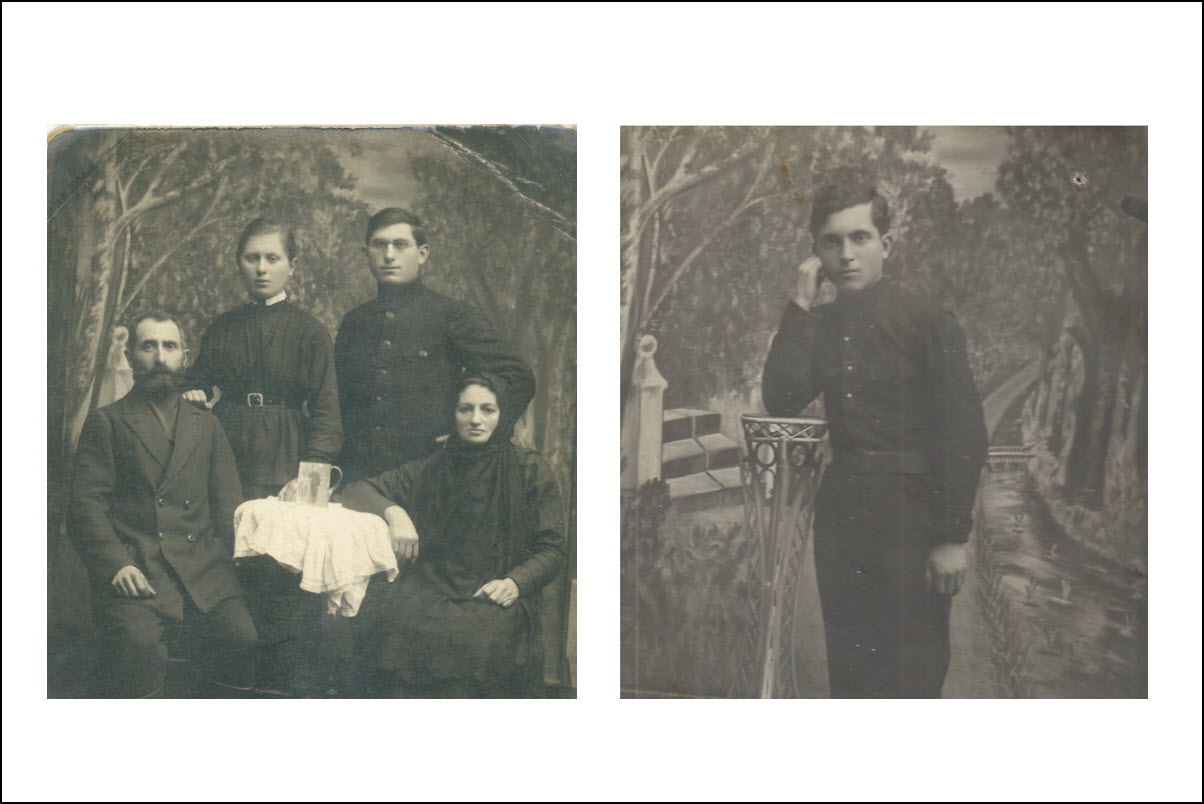

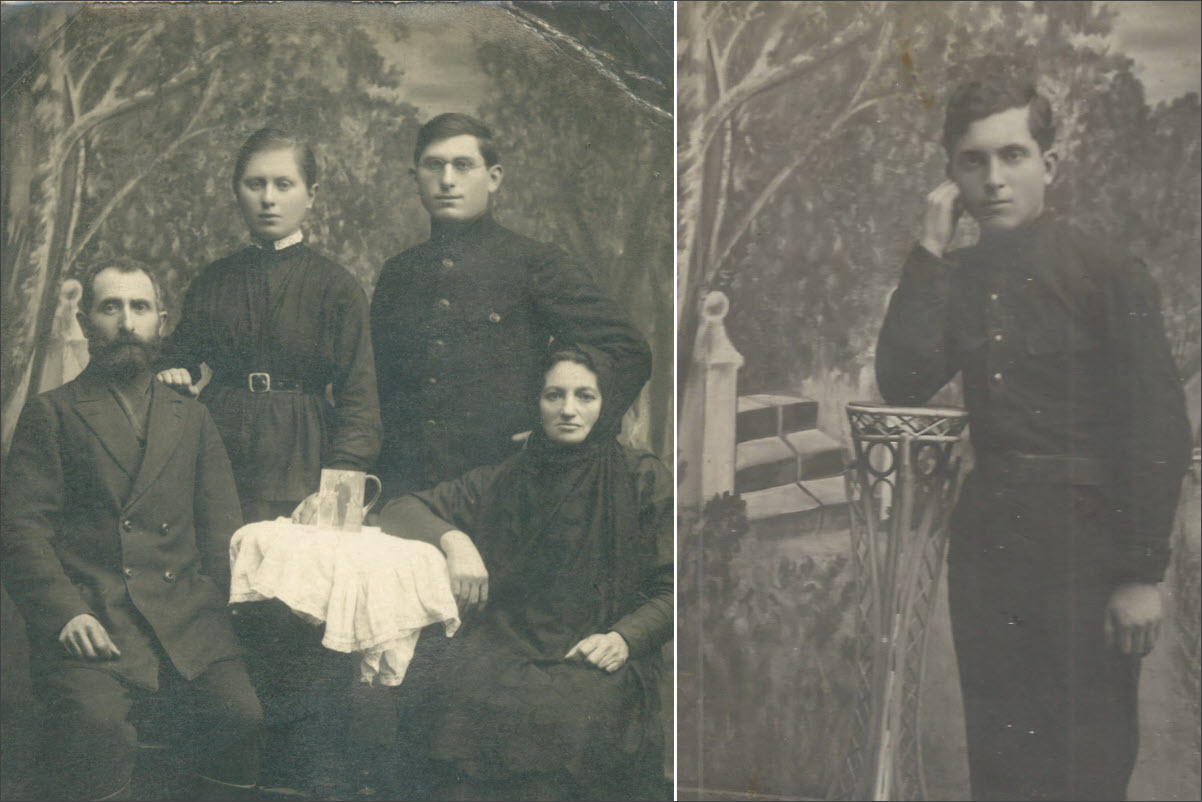

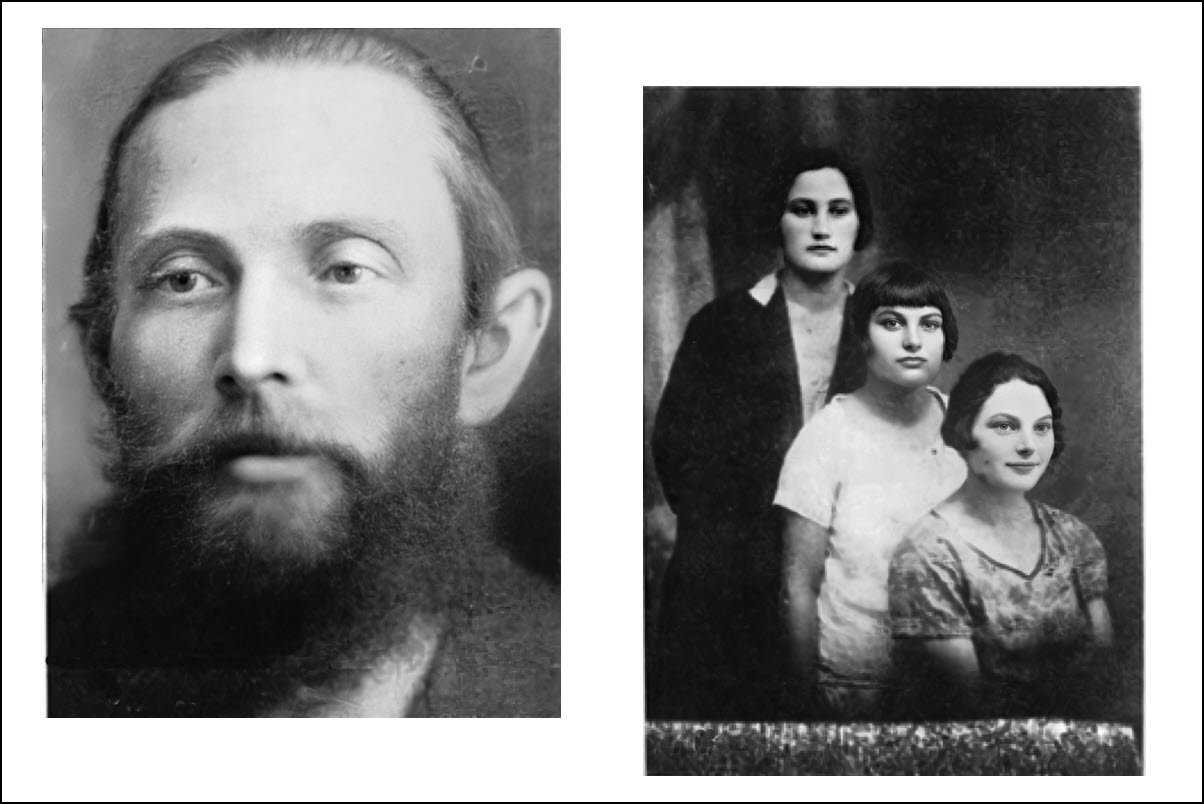

The Halperin family with aunt Sarah (Shrentzil) Gertnich, sister of Rivka (Shrentzil) Halperin.[3] Courtesy of Miriam Aharoni.

The Halperin family with aunt Sarah (Shrentzil) Gertnich, sister of Rivka (Shrentzil) Halperin.[3] Courtesy of Miriam Aharoni. Halperin family haberdashery in Mlynov with US visitors in 1935[4] Courtesy of Miriam Aharoni.

Halperin family haberdashery in Mlynov with US visitors in 1935[4] Courtesy of Miriam Aharoni.Lipa Halperin's Essays

"The Mill," pp. 13-16.

Lipa reflects on the narrow perspective of Mlynov residents who are not interested in anything outside of daily life, the worries of earning a living, and fulfilling religious obligations. They do not take an interest in or ask questions about what is beyond their immediate concern nor about the history of their town. The researcher who comes to town asking questions, they see as eccentric and not as in fact a harbinger of the future. Instead, they rely on stock answers about the past and offer quasi-religious and folkloric accounts for the name of the nearby river. Lipa's criticism is sharp, but softened with subtle humor.

In many ways, Halperin recalls the very traditional life of a town that had not yet been penetrated by a growing interest in history that was, when he was a boy, beginning to reach parts of Russia in the early 20th century. Although the essay is entitled, “The Mill,” Halperin recalls only the broken remnants of a mill that had burned down sometime in the past and whose blackened posts stuck out of the Ikva river and out of the snow in winter. The mill is arguably a metaphor for Halperin, both for the Mlynov residents’ relationship to their past, which was submerged in time, and perhaps for their future, of whom only remnants remain. Lipa being one of them.

"When I Was A Lad," pp. 153-56.

A precious series of memories that Lipa shares about his childhood experiences in Mlynov with his friend Yoseleh that include "playing horse," the local Catholic Church where Lipa saw Jesus on the Cross for the first time, the hill remembered as "Mount Sinai," and the evacuation during WWI. All the memories are seen through the eyes of a child and through the prism of legends and fables of those years.

"A Young Man Writes to His Brother in the Land [of Israel]," pp. 202-203.

Lipa includes a despondent and angry letter written to him by his younger brother Abraham when Lipa was already in Palestine. The letter appears to have been written in 1939 or 1940 and possibly under Russian occupation. Abraham laments that he is miserable at school, with a teacher who kills the material. He dreams of going to Palestine to fight on behalf of his people and not live in exile like the Jews of the Spanish Inquisition who went like lambs to their slaughter.

Notes

[3] The Halperin Family. Lipa Halperin (center), his mother Rivkah Halperin (seated right), Rivkah's sister, Aunt Sarah (Shrentzil) Gertnich, her baby Faiga(front). Standing (ltr) sisters Elka, unknown, sister Batya, brother Abraham, unknown, sister Chaika. ↩

[4] Back row (l to r): Lipa’s father, Israel Halperin, first cousin, A. D. Hirsch visiting from the US. Next row: Lipa’s sisters, Chaika and Elka, A. D.'s wife-Ellen Hirsch, Lipa's mother Rivkah (Shrentzil) Halperin. Seated: siblings, Batya and Abraham. ↩

***

Aaron Harari (née Berger), [Kibbutz] Merhavia

Ahron (Aaron) Harari (1908–1984) was one of the eight individuals on the Book Committee that produced the Memorial Book. During a trip back to Mlynov in the winter of 1937–1938, his camera captured the majority of images of scenes and characters that appear in the Memorial volume and that define our image of the shtetl. The evocative story of that trip back to Mlynov, in which he felt alienation from his hometown, is one of the moving essays that Aaron contributed to this volume.

Aaron was born Ahron Berger in Mlynov on April 7, 1908. He was youngest son of Golda (Kentor/ Kantor) and Wolf (Zeev) Berger and one of six siblings: Israel ("Sol) (1898–1977), Shaul (1901–1976), Hannah (1903–1942), Kalman (Karl) (1906–1990) and Rosa (1910–1994). The full saga of the Berger family reaches from Mlynov, to Chicago and Palestine. By the time he was six, his oldest brother Israel ("Sol") had already left the house for America to join his first cousins in Chicaog. Sol arrived in Chicago in 1914 just before WWI broke out.

During WWI, Aaron's family was twice forced to flee from Mlynov as the Eastern front moved back and forth near the town. During this time, they wandered as refugees from town to town. In Aaron's later recollections about this period, he recalls seeing dead and dismembered soldiers being buried during one of these periods of wandering. After the war, the family returned to Mlynov. At some point Aaron's eldest brother, Shaul, had enlisted or been recruited to the Red Army and eventually married his cousin Rachel Cantor and settled in Mogilev-Podolsky, Ukraine and had three daughter. Two of his daughters would later migrate to Israel and the United States.

Following the War, Aaron’s brother Kalman (Karl) wanted to join their older brother Israel ("Sol") in Chicago. But immigration quotas had tightened in the US. To make his way there, he had to go via Buenos Aires where he was photographed with a group of young men from Mlynov who were also trying to sneak into the US.

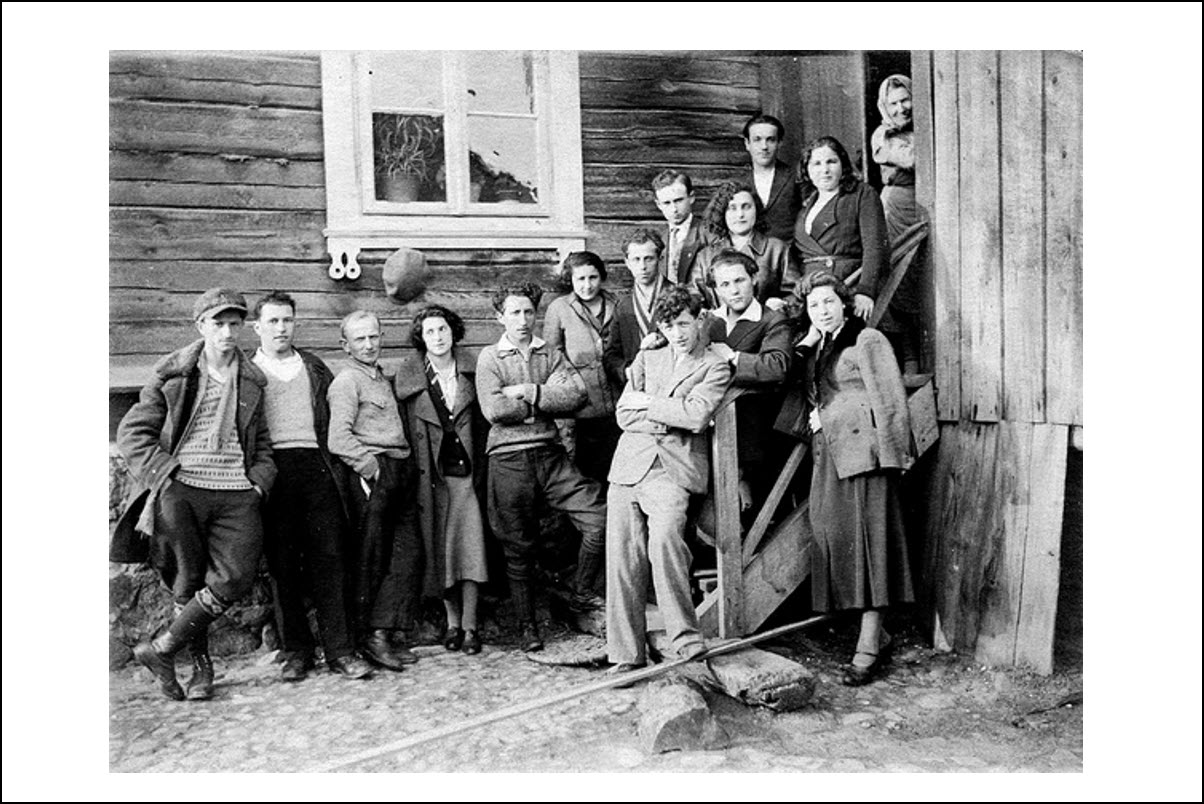

During the 1920s, after Mlynov had become part of the newly formed Polish State, Aaron became a Mlynov leader in the revival of the Zionist youth group, HaShomer Hatzair, in which his younger sister Rosa also participated. After a period of preparatory training (hachsharah) on a kibbutz in Slonim, Aaron helped lead a preparatory kibbutz near Mlynov. His sister, Rosa made aliyah in 1933 with the Planty group, and Aaron, who was tied up in leadership at the time, followed in 1934 and joined Kibbutz Merhavia. There he became a nationally recognized specialist in sheep breeding. In the winter of 1937–1938, Aaron return to Mlynov for a visit. The stated purpose of the visit was to study sheep breeding techniques. But Aaron had in fact come back for another purpose. He wanted to help the sister of one of his Kibbutz members get around British customs and make aliyah. To do so, they planned to carry out a fictitious wedding, enabling her to travel on his documentation. This visit was the last time his saw his parents and older sister, Hannah, alive. They would be killed in the ghetto liquidation in 1942.

Additional reading:

You can also download and read the detailed saga of the Berger family and the transcript of Aaron Harari's reflections on his life.

Essays By Aaron Harari in this volume:

"The Cologia [The Swamp]," (Hebrew), 25–26.

In this essay, Aaron nostalgically recalls childhood memories of the pond at the center of town which they called “Cologia" or "swamp." Around the circumference of the Cologia were many of the local shops and children would go out to play along its banks or skate on it during the winter, during breaks from cheder.

Aaron recalls the sounds of frogs croaking around the Cologia in summer. In winter, the Cologia would frequently fill up with water and reach the steps of the houses that were situated around its perimeter.

Aaron tells the story of how the Cologia originally came into existence. It was the spot from which the town harvested wood for houses and clay for mortar.

"Culture, Education, and Social Life in the Small Town," (Hebrew), 66–68.

This essay reflects on the period just after WWI when the town of Mlynov was coming back to life. Under the newly formed Polish State, the culture of the town was in transition away from the culture concentrated in the Shulman house which centered on Russian literature, towards a growing interest in Zionism and Hebrew. Harari recalls the celebration of the Balfour Declaration, the emergence of a modern Hebrew school, Tarbut (Culture), and the beginnings of the Zionist youth group, HaShomer HaTzair, under the leadership of Shmuel Mandelkern and Harari himself.

"The Youth Movement, “The Young Guard” (Hashomer Hatzair),"(Hebrew), 69–74.

Continuing the discussion from his previous essay, this one expands on the discussion of Zionist youth groups in Mlynov and the critical role of Shmuel (Samuel) Mandelkern in bringing those groups to life. Harari provides a window into how the groups developed, their importance to the Mlynov youth and the activities of the groups that drilled in military formation, studied poetry, sang songs, and learned Hebrew.

"Jewish Farmers in Mlynov [H]," (Hebrew), 75–76.

A personal bittersweet essay by Harari, talking his father and uncle's love of agriculture and the difficult of doing so in Poland. Harari recounts how they rented land from a local noble and then after they had cleared and prepared the ground, he broke the contract. By this time, Harari has been living in Palestine on a Kibbutz for several years and his nostalgic look back recalls his own role in helping with the animal husbandry and agricultural efforts before and after school. The essay ends with the painful acknowledgment that his uncle had wanted to make aliyah and practice agriculture in Palestine, but that Aaron had not been able to help him get out.

"Visit to Mlynov in 1938 [H]," (Hebrew), 77–79.

One of the most moving essays of the volume, Harari recounts his feelings of alienation when he arrived in Mlynov in the winter of 1937–1938. Though everything was familiar, everything was also strange. Harari captures the realization that his life in Palestine has fundamentally changed him and made what had been his home town seem like a foreign place. Harari recalls how proud his father was of his son and pressing him to attend the synagogue, and take an honor, though Harari was not in the habit of praying anymore. Among the more evocative moments, other residents of the town would grab his coat and smell it as if there might be something special from the smell of Eretz Yisrael.

***

Yankev Holzeker, (also Yaakov Golceker), (Israel)

Yankev (Yaakov) Holzeker contributed an essay to the Memorial book. He was a great-grandson of Avraham Holtzeker/Goldseker and a grandson of Avraham's son, Yankel, one of the five original Holtzeker brothers who arrived in Mlynov. Yankel/Yaakov was thus a cousin of the other Holtzeker/Goldseker descendants who contributed to this volume: Boruch Meren, Eta (Goldseker) Fishman, and Baila Holtzeker, each of whom descended from one of Avraham Holtzeker's five sons: Hirsch, Moishe, Yankel (or Yaakov), Shimon and Yoel. This Yankel/Yaakov's lineage from the ancestor Avraham was as follows: Avraham-> his son Yankel-> his son Moshe-> his son Yankel/Yaakov (the author of the Memorial book essay).

The information about Yaakov was reconstructed from Yad Vashem records, from the list of martyrs in the Memorial book, and eventually contacting a son of this Yaakov Holtzeker. Yaakov’s grandfather, his namesake, Yankel Holtzeker, married a woman named Rivka. They had two sons, Yehoshua ("Yeshea") (1878–1942) and Moshe (1880–1942). Moshe, married a woman named Toba Klein (or Kaliner) referred to in his essay, as "Reuven Ostriyever's daughter" because the family was from Ostrog (Ostroh today). Toba's sister, Mahla, married another Mlynov man named Abraham Gelman.

Moshe and Toba, had seven children including this Yankel/Yaakov: Chaya Bejla (1905–1942), Yojna Reuben (1907–1942), Rywka (1912–1942), Genia (1915–1942), and Pesia (1918–1942), and another son Avraham. Only Yaakov and Avraham lived through WWII. From Yad Vashem records, we also learn a little about each of the siblings who were murdered: Chaia Bila or Bejla Khaia (1905–1942) was a seamstress and single. Yojna Reuben (Yona Reuven) (1907–1942), was a house painter, metal worker, journalist, teacher. He married a woman named Roza. During the war he was in Lanowce, Krzemieniec, Wolyn and died there. Rywka (1912–1942) was a teacher, and married to Avraham Kolton. Genendl or Genia (1916–1942), was a seamstress and single. Pesia, (1918–1942), was a seamstress and single. No information is available about how Yaakov and his brother Avraham survived or made their way to Palestine/Israel. However, we do know that Yaakov went back to Mlynov for a heartbreaking visit in 1945 after he was released from the Russia army.

Yaakov's Essay

"My Hometown Mlynov," (Yiddish), 226–228.

In this short essay, Yaakov reminisces about residents bathing in the Ikva River, the Zionist Youth Groups, and observance of Simhat Torah at the home of Nahum Teitelman. He briefly recounts the horrifying experience of returning to Mlynov after being released from the Red Army. His words speak for themselves:

The shtetl looked like a catastrophic graveyard. Every little footpath was saturated with Jewish tears and blood. I got frightened as soon as I approached my shtetl. Everything was blocked and ruined. All the streets were a mountain of stones. The only Jewish houses remaining were occupied by Christians. Not a trace remained of the Study House and the other synagogues. Everything had been destroyed. Wild grass grew on the streets. I went only to my brother's grave, located on Kruzshak, between Mlynov and Mervits. I wept heartily because of the dark fate that had befallen us.

Read more about the Goldseker family in Mlynov and what we know about Yankel's line.

***

Moshe Iskiewicz (Isakovich), (Israel)

Moshe Iskiewicz (also spelled Isakovich) was one of four children born to Eliezer (Leazar) and Chaya Faiga (Grin) and the only one of his family who was not killed in the Shoah. The four siblings were: Shlomo (1921–1942), Raizel (1927–1942), Szeindel (1935–1940), and Moshe, the author of this essay.

The day the Germans attacked the Russian occupied part of Poland, Moishe was one of five young men who fled East by bicycle towards Russia's earlier border, as reported by Yechiel Sherman in his essay in this volume. They made it past the old Russian border and reached Zhitomir. There they got on trains in the direction of Kiev. Somewhere before reaching Kiev, Yechiel lost track of Moshe and several other companions. How Moshe survived in Russia is thus not known.

According to the list of martyrs in the Memorial volume (p. 431), his brother Shlomo was missing after the battle of Stanlingrad in August 1942. The Yad Vashem records filled out by Moshe provide some additional information. Moshe’s father, Eliezer, was born in 1896. He was the son of Sheindel and Shlomo Iskiewicz and was a textile merchant. Moshe’s mother, Chaya Faiga, was born in 1896, part of the large Grin family in Mlynov. Her parents were Leib and Dvorah Grin. It is unknown at the time of this writing when or how Moshe made aliyah.

Moshe Iskiewicz's Essay

"Impressions and Memories," (Hebrew), 88–89.Looking out through the window of his house, Iskiewicz recalls the scenes of Mlynov residents walking by on their way to the study house, some rushing quickly others with no care in the world. Iskiewicz recounts as well his memories of various teachers in town, those that slapped the students and those who inspired.

***

Shirley Jacobs (née Barditch), Bronx

Shirley (Barditch) Jacobs (1905–1983), born Sura Borodacz, was one of five children of Isidore Barditch (originally Yehiel Borodacz) and Bessie (originally Bassa Ferteybaum). Shirley's father, Yehiel, was born in Lutsk and her mother, Basa, was probably born in Mlynov like her mother's brother.[5] Shirley’s older sister, with whom she was very close, was Sylvia Barditch-Goldberg, who was on the Book Committee for the Mlynov Memorial book and is another contributor to this volume. Sylvia in the essays she contributed describes their grandparents, Itcek and Malia Ferteybaum, who lived in Mlynov. Sylvia describes Itcek as a Stoliner Hasid and as "starosta," starosta being a slavic term indicating a leadership position in a range of civic and social contexts.

Both Shirley and Sylvia were born in Lutsk, along with their three brothers, Paul "Peretz" (1895–1961), Meyer (1907–1922), and Benjamin (1908–1979). On holidays and for vacations, the family would go to Mlynov to visit with their grandparents.

Shirley's father arrived in Baltimore in July 1910. He was joined by her uncle (her mother's brother) Usher (who became Harry Tatelbaum). The rest of the family would not join him until after WWI. Shirley arrived in New York in October 1921 with her brother, Peretz and his wife, her sister Sylvia, and brother Benjamin. For some reason, their mother and brother "Majer" were delayed and arrived a few weeks later at the beginning of November.

The family settled initially in Baltimore with their father. Not long after their arrival, a tragic hit and run accident killed their younger brother Meyer on May 5, 1922. Unable to cope with the memory of the tragedy in Baltimore, the family, relocated to Brooklyn by 1925 except the older son Paul who remained in Baltimore with his family. In New York, Shirley married Benjamin Jacobs in October 1933, and they had three children, Marilyn Israel, Arlene (Jacobs) Feig, and an older son who died shortly after childbirth.

A photo of young Marilyn Israel below indicates that the family was socializing with another Mlynover, "Henia Arelas" (i.e., daughter of Aaron Hirsch) and mother of the Yiddish poet, Aleph Katz, and one of the Hirsch siblings who migrated to America.

Shirley's Essay

"A True Event in Mlynov from 96 Years Ago," (Yiddish), 196–197.Shirley here recounts the interesting and disturbing story of a Mlynov man who never returned home after going to collect a debt from a Czech man who borrowed money from him. The missing man was Daniel Arelas, "Arelas" here meaning he was "son of Aaron" (Hirsch). When Daniel was discovered murdered on the road the next day, his fur hat was missing. The ghost of the deceased Daniel visited the town's residents alerting them as to where they could find the missing fur hat, which they indeed found. Daniel's wife was pregnant at the time and a son was born after his death. That son came to New York.

The story sounds alot like fiction. But we know that Shirley knew the Hirsch family because a photo of her mother, her daughter Marilyn Israel and sister Sylvia (see above) appear in a photograph in America with "Henia Arelas" (i.e., Anna daughter of Aaron Hirsch), the sister of the murdered Daniel Arelas. It seems plausible that Shirley heard the story from her mother and/or Daniel's sister, Anna Katz. Whether it was true or not is of course another story.

Additional reading:

You can read the essays written by Shirley's sister Sylvia about their grandfather, Icik Statrosta, and her visits to Mlynov. You can also read more about "The Mystery of Sylvia Goldberg."

Notes

[5] Shirley's mother's brother, Usher (Harry Tatelbaum) lists his birthplace as Mlynov on his passenger manifest in 1911. He arrived in Baltimore with two other Mlynov men. Since her brother was born in Mlynov, and her parents lived there, I suspect that Sylvia's mother also was born there. Her later US records, however, are inconsistent. When she arrived in 1921 her passenger manifest says she was born in Varsovic (perhaps Varkovychi) and her Petition says she was born in Lutsk. ↩

***

Yitzhak Lamdan, (Israel)

The poet, Yitzhak Lamdan, is probably the best known of the individuals born in Mlynov because of his important role in shaping Zionist ideology and Israeli national identity with his famous and influential poem, “Masada.”

Born in Mlynov in 1899 into an affluent family as “Itzik Yehuda Lubes” or Lobes (later Yitzhak Lamdan), Lamdan lived in Mlynov until the outbreak of WWI in 1917 and the civil wars that followed. During this period, he was uprooted and wandered through Southern Russia with his brother before joining the Red Army. In 1920, after his parents’ home was destroyed and his brother was killed, Lamdan immigrated to Palestine as part of a socialist youth group in what has come to be known in Zionist history as the “Third Aliyah.” His poem “Masada” was written between 1923 and 1926 during his early years in Palestine while he was also involved in manual labor of various sorts.

Additional reading

Yitzhak Lamdan was finally able to return home to Mlynov for a visit in 1932. A charming story of that visit, "In the Presence of Yitzhak Lamdan" is recounted through the eyes of a younger boy who hero worshipped the older poet.

Lamdan's Poetry Selections:

"Poems (Selections) ," (Hebrew), 83–84.A selection of evocative poems from Lamdan especially when understood against the backdrop of Lamdan's visit back to Mlynov in 1932. They represent very moving reflections from a young man who has left religion behind and who is imagining a conversation with his father about his life in Palestine. He struggles with how much to reveal about the difficulties he is facing in his life, knowing his father is hanging on his every word. In the selections that follow, Lamdan voices the overwelming challenges of chasing the dream of Zionism in a "Boat Torn to Pieces" and "Without Shabbat," giving vent to the anguish felt by his generation of immigrants.

***

Helen Lederer (née Gelberg)

Helen Lederer was born "Chultzie Gelberg" in Mlynov in 1903. She became Helen Dishowitz and then later Helen Lederer in the United States. She was the eldest daughter of Moishe Gelberg/Goldberg and Gitel (Weitzer). Helen’s siblings include: Sarah Lewbel (1906–1987), Avrum Gelberg (1908–1954), and Gershon (later Jack) Gelberg (1910-1970).

Helen’s father, Moishe (1875–1967), was one of seven children of Labish Gelberg and Eta Leah (Schuchman). In 1911, he was the first of the four Gelberg children who immigrated to the US where he settled in New York and became Morris Goldberg. He was soon joined by his sister Sura (Sarah Gelberg) who subsequently married and became Sarah Spector. Moishe intended to bring his family to join him in New York, but when WWI broke out the Gelberg family back in Mlynov became refugees. Helen, about eleven at the time, must have been terrified leaving Mynov during the War with her father far away in the US. The family was eventually reunited in the US after the War.

Helen's Essay:

"In Pain From The First World War," (Yiddish), 147–148.Life on the road as a WWI refugee from Mlynov is described in this moving essay through the eyes of a young girl, who wanders with her family from town to town as the Eastern front got close to Mlynov. This is one of the few detailed accounts of the Mlynov evacuation.

Additional Reading

Read the Gelberg/Goldberg story.***

Yosef Litvak (Jerusalem)

Yosef (Josef) Litvak (1917–2001) was one of the eight individuals from Mlynov who oversaw the Mlynov Memorial Book. He had an amazing life's journey.

Yosef grew up in Mlynov but he was not born there. He was born in Kiev within one month of the Communist Revolution, which would trigger his family to flee and make their way to Mlynov where his mother had been born. His father was Motl-Meir Litvak (1881–1942) and his mother was Dvora Rifka (Lamdan) (1889–1942), the sister of the poet, Yitzhak Lamdan. Dvora was born in Mlynov in 1884 but moved to Kiev in 1911, possibly following a sister, where she met and married Motl-Meir. Yosef and his sister, Pnina ("Pepa") (1913–2003), were both born there. Up until the Revolution, life was good and the family enjoyed the culture of Kiev and later had fond memories of their special attachment to opera in this period, which would not last long after Yosef was born.

During this time Yosef's father was a business manager for a wealthy Jewish contractor who built train stations for the Tsarist government. Following the Communist Revolution, the family fled Kiev due to pogroms and because the Bolsheviks considered Yosef's father, Motl-Meir, to be part of the bourgeoise; their lives and fortune were therefore at risk. Yosef later shared with his son, Meir, a story of a childhood trauma that occurred during this time: When he was a baby, there was a pogrom and the family went into hiding in the cellar; to keep him from crying they had to stuff rags in his mouth. From this and other traumas that followed, Yosef would wake up the middle of the night screaming later in life.

The Litvak family fled Kiev with a cart, a horse, a 5-year-old daughter and Yosef, a 1-year-old baby boy. It took them a year to reach Mlynov where Dvora had been born and where they resettled. Yosef later described Mlynov to his son as "a poor muddy stinky shtetl." The Litvak family tried to get a visa to the US, but failed following the 1924 laws restricting immigration to the US. Motel-Meir tried his hand at a number of business ventures but they lived in great poverty until the end.

In Mlynov, Yosef was very active in the Zionist youth group, Hashomer Hatzair, which he writes about in his essay below. In the 1930s, the right-wing Zionist Youth Group, Betar, opened a smaller branch in Mlynov. Yosef served there as a group-leader and later as the branch sercretary. In 1937, Yosef’s sister, Pnina, was able to make aliyah. Two of her Lamdan relatives were already there. Her uncle Yitzchak Lamdan, who had by this time become a famous poet in Mandate Palestine, had arrived shortly after WWI and her aunt Malka (Lamdan) Mandelkern had made aliyah in the mid-1920s. In Palestine, Pnina got married and and became Pnina Holtsman and had three sons: Arye, Mordechai (Motti) and Joshua (Shuki). Yosef also tried fervently to get a certificate to Palestine from 1936 to 1939, but failed because of the British restrictions.

During the Soviet occupation of Eastern Poland, beginning in September 1939, Yosef was suspected of being a Zionist, which he denied. This later saved his life. The Soviets gave him a role as an accountant which he loathed, and so he eventually moved to Rovno, the district seat, and managed to get himself into a teacher's college there.

When Nazis invaded on June 22, 1942, Yosef reported as was expected to the military draft office, where he waited half a day, before he told to go home and come back the next day. But the next day, June 23rd, all the Soviet officials had already fled the area. He tried to hire a peasant to take him back to Mlynov to assist his parents according to a prearranged plan with them. But Mlynov was more to the west, and they were told that the Germans had already occupied Mlynov and they had to turn back. The wasted day at the draft office haunted him the rest of his life. His parents were killed in the ghetto liquidation in October 1942.

Yosef managed to flee eastward into Russia, walking, and hanging upright on the outside of trains filled with other fleeing refugees. He reached Kharkiv where he had family on his father's side but had to flee eastward again when the family was evacuated by the Soviets. At some point in this journey he was conscripted into the Red Army and like other recruits from the East, whom Stalin distrusted and would not put at the Front, he was sent further East and put to work in hard labor as a coal miner. At one point, a mining accident occurred and he was left in the dark for seven to eight hours. He recalled this as the worse experience of his life and thought he was surely going to die.

At the risk of his life, Yosef finally deserted the army. Though subsequently arrested, he managed to convince them that he was headed to the Front to enlist and was released. At some point, he managed to buy false papers in Chelyabinsk and in 1944 after three turbulent years in the Soviet Union, he finally managed to join the local pro-Communist Polish army and sneak out of Russia with them to reach Lubin. There, he deserted their camp and found a group of Jewish Zionists involved in the Bericha Movement, which was helping Jews illegally get out of Europe.

Joining with group of other refugees on a new route out of Europe, they pretended to be Greek, traveling through Romania, Poland, and Bulgaria before finally reaching Greece. In Greece, where the ruse could no longer work, they poised as deaf and dumb people. Finally, in Greece, Yosef was able to embark on an illegal ship that the Hagganah had organized, one of the first ships to navigate past the British into Mandate Palestine. He remembered it later as a miserable creaking ride, but they managed to get through and landed on November 21, 1945, south of Haifa. At night, they were brought to shore by Haganah activitsts and sent to Kibbutz Ein HaMifratz on Haifa Bay. A half year later, he transferred to Kibbutz Nir David, near Beit Shean, where there were others from Hashomer Hatzair.

Yosef subsequently married, had four children, nine grandchildren and many great-grandchildren. In 1947 he left the kibbutz, went to the US to study sociology and finished a BA in social work. He subsequently returned to Israel and completed an MA in modern Jewish History, and for his PhD wrote on Polish Jewish refugees in Soviet Union. He passed away on January 1, 2001. His family calls these granchildren and great-grandchildren their father's victory over Hitler.

Yosef Litvak's Essays:

"The Town of Mlynov," (Hebrew), 53–59.

Yosef shares a number of memories of Mlynov, including the beauty of the area, the origin of the town's name and its description, the centrality of the local nobleman, "the Count," to the town's economic life and the livelihood of its residents. His account includes a discussion of the differing religious perspectives of the town's residents before shifting his focus to the growth of the Zionist Youth Groups in town.

"The Mlynov Community at the Beginning of the Soviet Occupation," (Hebrew), 283–286.

One of the few essays in the volume that delves into the period when Mlynov was occupied by the Soviets between September 1939-June 1941. Litvak recalls the hardships that fell on the community by the socialization of commerce and the general hostility towards religion and Zionism.

"Portraits," (Hebrew), 242–244

Yosef evokes the memory of four Mlynov people he remembered and admired: first, the learned Yehuda Leib Lamdan, the learned father of the famous poet, Yitzhak Lamdan, and a moral authority in the Mlynov community ; second, Yosef recalls his own father Mordechai Meir Litvak (also called Motl Meir) Litvak, who was a trusted community worker and active Zionist, and who oversaw and administered several organizations. "Though he was weighed down by worries about livelihood from his small fabric store, he dedicated a lot of his time to public activities." Third, Mordechai Chizik, "the" Hebrew teacher in town responsible for so many learning the language and fourth, Batya Mohel, who was active in Zionist youth groups and who perished with her family.

"The Litvak Home," (Hebrew), 413

Yosef reflects on his own family and especially the activities of his father who helped oversee several organizations.

"A Memorial Candle Chaia Kipergluz," (Hebrew), 242.

A short reflection on Chaia Kipergluz who was born in 1919. She suffered abuse under the Russians for her Zionist activities and then under the Germans she was killed with a group of young people for being a Communist.

***

Boruch Meren (Baltimore)

Boruch Meren was born in Mlynov in 1908 to Ben Tzion Meren and Miriam (Goldseker). His mother's father was Hirsch Goldseker, one of the five Goldseker brothers in town.

Boruch and his sister, Seril, grew up in a religious household and his father did not allow him to get involved in the Zionist Youth Group Hashomer Hatzair. But Boruch had fallen in love with his sweetheart, Rosa Berger, before her aliyah in 1933 and she was able to get him a certificate to make aliyah in 1938. Had she not done so, he would have died in the Shoah with the rest of his family. An account of their courtship is endearing and the photos he sent her open a window into life in Mlynov in the 1930s for young men who were hoping to get out.

In the meantime, life in a Kibbutz had changed Rosa and their relationship did not work out when they were reunited. Fortunately, Amelia “Milka” of the Mlynov Shargel family came from Baltimore to visit in Palestine and possibly to be matched up with Boruch. She too had been born in Mlynov and had immigrated to the US via Mexico, arriving in 1929.

While in Palestine in 1938, Boruch went to visit Moishe Fishman in Moshav Balfouria. Moishe had been born in Mlynov and had made the decision to make aliyah with his family in 1921. His leave taking was sharply etched in Boruch's mind, and in one of Boruch's essays he wrote about the rukus Moishe made in Mlynov when he made the decision to make aliya from the shtetl. Boruch reflects on that scene and the conversation he had with Moishe 27 years later when Boruch made it in Palestine too.

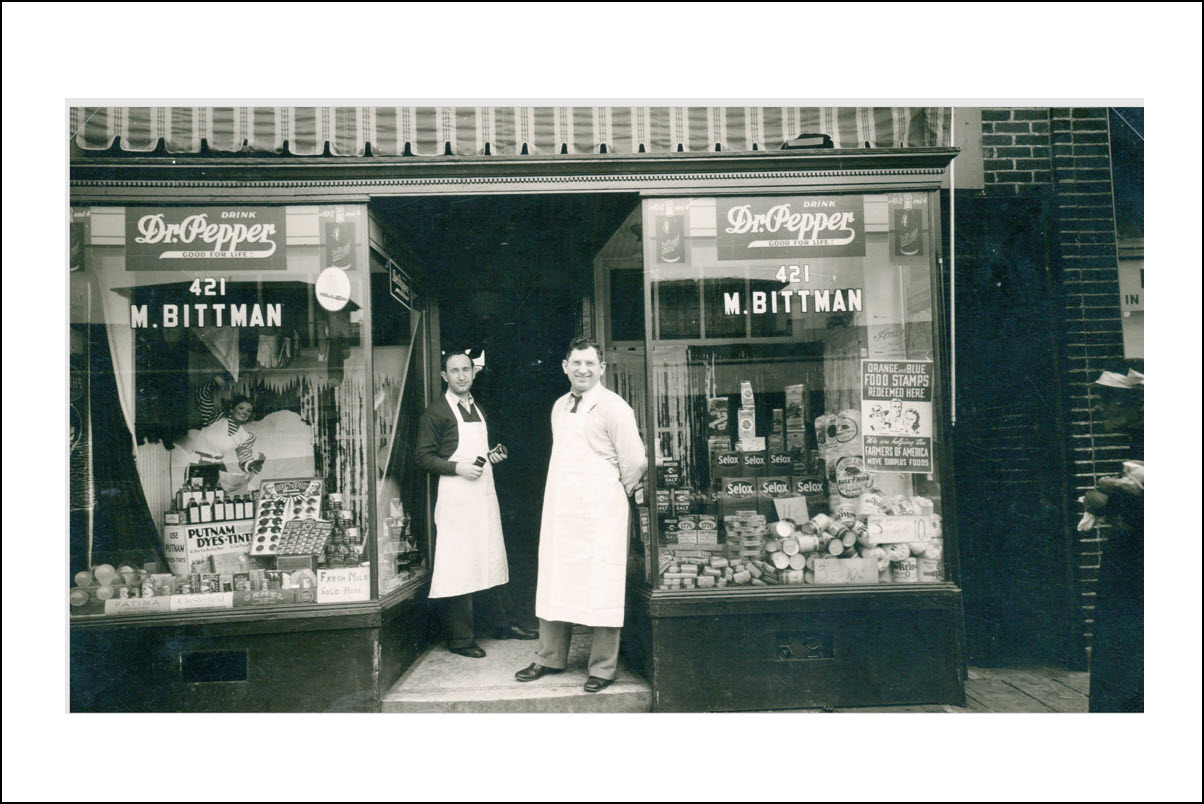

Boruch and Milka got married during her visit to Palestine and she was able to get Boruch papers to bring him to Baltimore where he settled and became a grocer. Amelia and Boruch had a son, Allen J. Meren, and two grandchildren.

In 1949, in search of Mlynov survivors and his own family, Boruch put an ad in the Jewish Forward. The ad was read excitedly by Liba Tesler, a Mlynov-born woman who had escaped the ghetto and survived a harrowing ordeal, moving from place to place in hiding, in a story narrated by her step-grandson. She responded to the ad and Boruch helped connect her to her cousins, the Marders, in Baltimore and other cousins in Brooklyn (George and Sylvia Barditch-Goldberg). The cousins helped Liba leave Europe and settle in Baltimore.[6]

Additional reading

Read the story of young love between Boruch and Rosa Berger. Or peruse the history of Milka's family, the Shargels.

Boruch Meren's Essays:

"A Good Deed (Mitzvah)," (Yiddish), 149–152.

Boruch recalls an incident after WWI when the Bolsheviks came to town and they were distributed among the houses in town. There was a Jewish boy from Rivne among them who was placed in their home. Boruch's father learns that the young man was living with his Jewish Bolshevik girlfriend and was not married by Jewish custom and so began an effort to get them to legally marry. The story wonderfully captures the new attitude that had emerged towards the insitution of marriage under the Communists.

"An Event in the Shtetl ," (Yiddish), 188–194.

Boruch reminisces about the clean air of the shtetl, the beautiful countryside and even the slaps of the teachers. The essay is full of very palatable memories of the people of Mlynov such as the greasy yamulke's of the men and includes a humorouse story of a prank on the town's wealthy class, led by Shmuel Mandelkern, involving the bath house. The prank stirred up the class tensions in the town and evoked new Communist and labor ideas about class differences.

"Khaykl Shnayder's Gramophone," (Yiddish), 199–201.

A humorous piece about a gramophone that passed from Boruch's Goldseker relative to Khaykl the tailor, who would fill the street with the sound of music. When the young men tease Khayl about his taste in music, the gramophone disappears forever.

"The First Aliyah from the Shtetl," (Yiddish), 220–225.

Boruch here recalls the stir that Moishe Fishman made in Mlynov when he decided to make aliyah with the family. In 1938, when he was able to make aliyah himself, Boruch tracks down Moshe in Balfouria and has a conversation with him.

"The Goldsekers," (Yiddish), 245–246.

Boruch's mother was Miriam (Goldseker), the daughter of Hirsch Goldseker. Hirsh one of the five Goldseker (and Holtzeker) brothers who had large families in Mlynov and like the other Goldsekers was known as "Hirsch Slobada" because they had been in Sloboda before Mlynov. Here he puts down a bit of information about the large Goldseker clan and what he remembers about them.

"My Father Ben-Tzion z”l," (Yiddish), 255.

A short poem about Boruch's father and should be read in conjunction with his next essay explaining how his father had ended up a teacher.

"The Treasure That Ran Out,"(Yiddish), 272–276.

A sadly somewhat humorous story about how Boruch's father tried to make a living but through a series of mishaps lost his shirt and turned to teaching instead. The essay touches on the pressures to go to the black market, the lack of economic opportunities in town and the tensions between husband and wives that arose over the need to provide for the family.

Notes

[6] On the story of Liba Tesler, and Boruch's role in bringing her to the States, see David Sokolsky, Monument: One Woman's Courageous Escape from the Holocaust ," p. 93. ↩

***

Asher Teitelman

Asher Teitelman led an extraordinary life. His story of survival, told in a book length account, is especially dramatic and moving. He was born in Mlynov in 1921 and is descended from the Teitelman and Gruber family lines. His parents were Nahum Teitelman (1890–1976) and Rachel (Gruber) (1894–1980), who were also first cousins.[7] His aunt Sonia (Gruber) Teitelman (his mother's sister) and her husband Mendel Teitelman are among the most prolific contributors to this Memorial volume.[8]

Asher (1921–2009) was the eldest of six siblings: Efraim Fischel (1922–1942), Shlomo (1924–1942), Shifra (Teitelman) Grossman (1926–), Yosef (1928–2015), and Sara Rivkah, who died at 9 months of age. The Teitelmans had a large home by Mlynov standards that also served as a granary and convenience store. Asher's father, Nahum, operated as a middle man in the grain market. Polish farmers would come to their home to sell their grain and while they were there they would buy necessities in the Teitelman store, where Asher, as he got older, worked with his mother. At times, there could be as many as ten horses and wagons at the Teitelman home / store doing business at the same time.

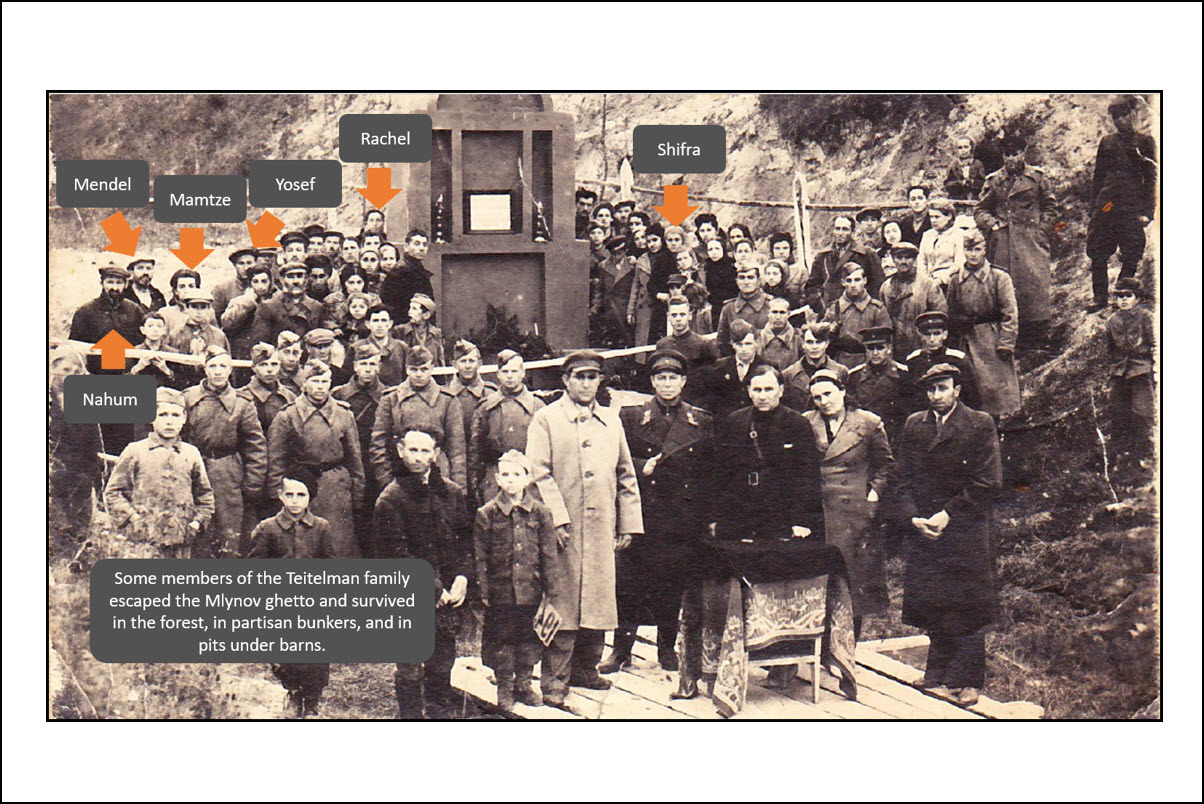

Asher’s two brothers, Efraim Fischel and Shlomo, were the first two Mlynov residents killed in October 1942 shortly after rumors started about the pending liquidation of the Mlynov ghetto. Asher and his family fled initially to a non-Jewish family outside of Mlynov who had conducted business with his father. In a harrowing and heroic story, the Teitelman family found hiding places in local forests, in pits in the ground, and eventually in bunkers in the Smordva forest, where Asher joined the partisans. During the last year of the war, as they ran out of options, the family eventually were hidden in a hole underneath the threshing barn of a Polish family, the Holatkos, who were subsequently recognized in Israel as “righteous gentiles.”

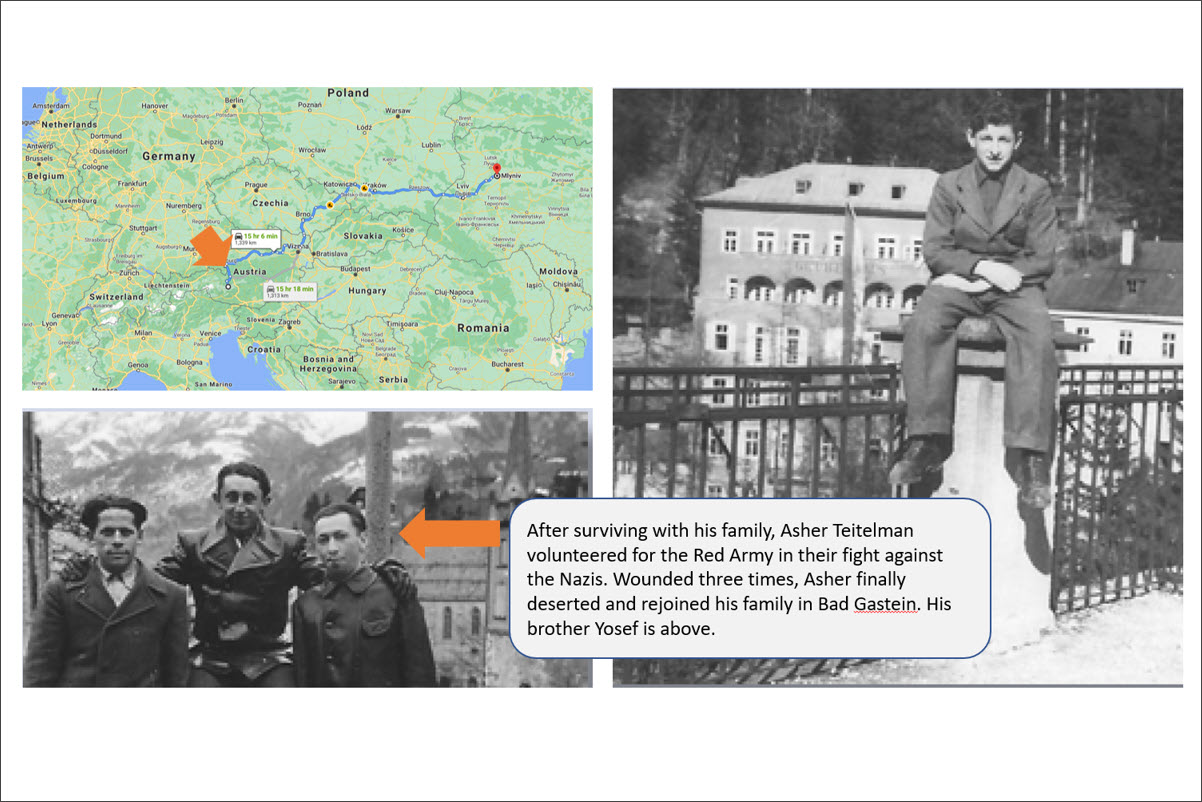

After the Russian liberation of the area, Asher volunteered for the Red Army, was involved in several battles against Nazi forces and was injured on three separate occasions. Following his convalescence, he eventually rejoined his family in Mlynov. Together, the Teitelmans made their way to the displaced person camp of Bad Gastein in Austria, where Asher met his future wife, Tova Genut, the mother of his children. For a time, Asher supported the illegal smuggling of survivors into American occupied territory. The family later made their way across Europe to Paris and then on an illegal ship, the infamous "Ben Hecht," headed to Palestine. Having reached the port of Haifa, they were turned back by the British and spent a year in the British internment camps in Cyprus. Finally in April 1948, only weeks before the State of Israel was declared, they received certificates and were allowed to make aliyah.

Asher and Tova had two sons, Ephraim and Shlomo, named for the two brothers Asher had lost. After Tova passed away in childbirth, Asher eventually remarried Raya Broida. His son, Ephraim, adopted the family name "Tomer," meaning "the date fruit," the Hebrew equivalent of the name "Teitelman."

Additional Reading

You can download the riveting book length story of Asher Teitelman's life, which also provides a window into his life in Mlynov as a child before WWII began. Right-click to download and choose "save link as..."

Understand the Teitelman family tree: Asher's parents were first cousins. And his mother's sister, Sonia, also married her first cousin. Watch this video to understand the complicated first-cousin marriages in the Teitelman tree.

Asher's Essay:

"The Massive Disaster (Shoah)," (Hebrew), 38–41.

Asher here recounts the shock among the Mlynov residents on June 21, 1941, the day they woke up to German bombing of the airfield outside of town. No one, not even the Russian soldiers who had been stationed there, expected the Germans to renege on the Molotov-Ribbentrop non-aggression pact, in which Germany and Russia had earlier agreed to split Poland in half. Nor did anyone believe that the strong Russian army would so quickly abandon its post and withdraw. But within days, the Russians retreated and the German troops occupied the town. Asher recounts the shock of the towns’ inhabitants those first days as the Nazi occupation and repression were first implemented.

Notes

[7] How are Asher's parents, Nahum and Rachel, first cousins? Nahum's father, Ephraim Teitelman, was the brother of Rachel's mother, Shifra (Teitelman) Gruber. Of course, what this means is that from Asher's perspective, his grandfather, Asher Teitelman, for whom he was named, was the father of both his parents. Confused? Watch this video to understand these complicated first-cousin marriages. ↩

[8] Rachel Gruber and Sonia Gruber were sisters, daughters of Joseph Gruber and Shifre (Teitelman). Both sisters married Teitelman men who were their first cousins and also first cousins to each other! ↩

***

Moshe Teitelman (later Moshe Tamari)

Moshe (Teitelman) Tamari[9] was born on May 20, 1910 as “Moshe Teitelman,” in the town of Varkovitchi (Warkowicze) but his family moved to Mlynov to make a living and where Moshe had cousins. Moshe spent a good part of his youth growing up there. He became Moshe "Tamari" sometime after making aliyah in 1933 and wrote and published a number of books and stories in Israel throughout his adult life, including edited volumes about towns that had been annihilated.

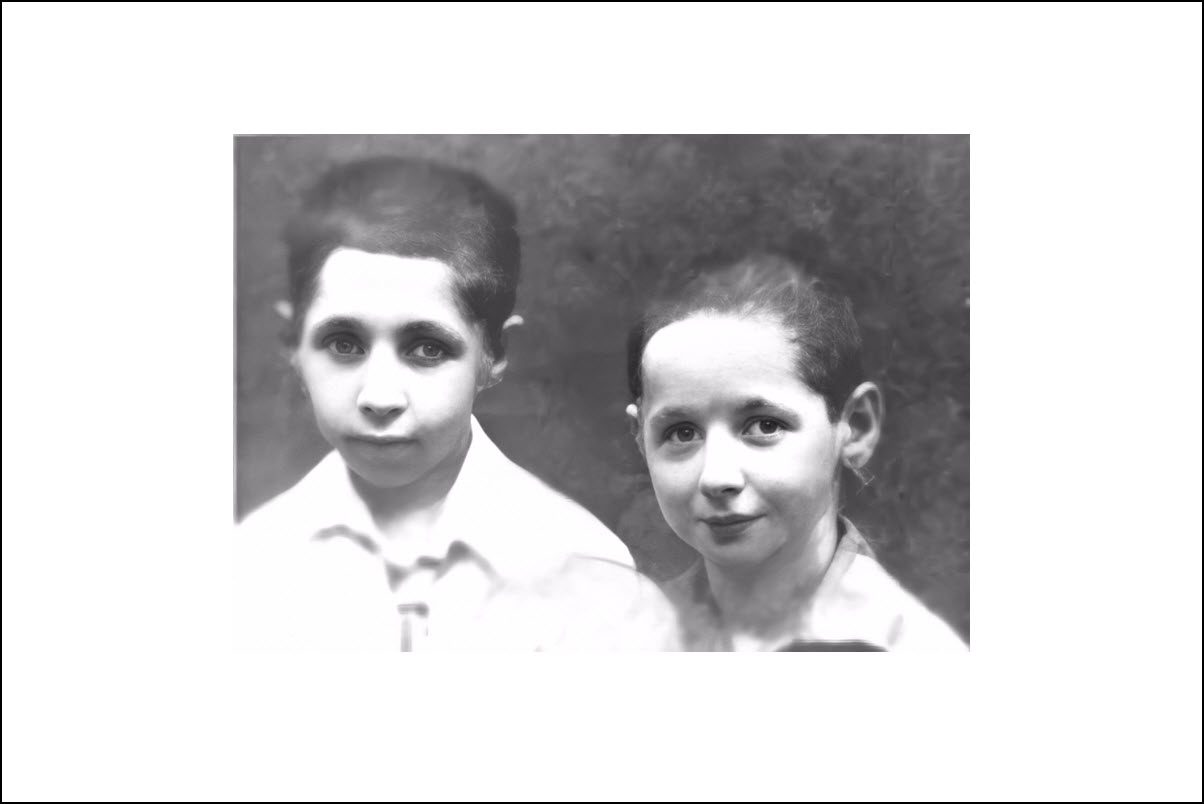

Moshe's parents were Anshel Teitelman and Zelda (Pekel) and he had one brother named Asher (see photo below). Moshe's father, Anshel, was an older brother of Nahum Teitelman from Mervits, who also published an essay in this volume. Moshe lost his parents and his brother in the liquidation of the Mlynov ghetto in October 1942.

While growing up in Mlynov, Moshe developed an aspiration to be a writer like his hero, the famous poet Yitzhak Lamdan from Mlynov. In a later essay in this volume, Moshe tells the interesting story of meeting Lamdan during his return to Mlynov in 1931. In pursuing his interest in literature, Moshe was a disappointment to his family who wanted him to be a rabbi, schochet (kosher slaughterer) or gabbai. But writing continued to be his lifelong passion. During his youth, Moshe got involved in the Zionist Youth movement, Hashomer Hatzair, and went to preparatory training (hachsharah) in Warsaw. When asked later in life what led him to leave everything behind and make aliya, he said simply, “the passion for literature”.

During his preparatory training, Moshe married another woman in the training kibbutz as a means for both of them to get certificates to make aliya to Eretz Israel. This was not an uncommon practice to circumvent the limitations that the British had set on aliyah. Aaron Harari used the same technique during his visit to Mlynov in the winter of 1937–1938 to help get a sister of a Kibbutz member out of Poland. Moshe arrived in Haifa in 1933 at the age of 23 and the couple immediately divorced. He worked for a time in the orchards of Rishon LeZion and then after growing season worked in construction expanding the road from Tel Aviv to Gedera. After a stint in Netanya, where it was difficult to make a living, he moved to Jerusalem and then Tel Aviv. In 1936 he married his wife Miriam.

In 1952, he began working for the Histadrut (the General Organization of Workers in Israel). In 1963, Tamari was sent to Brazil on behalf of the World Zionist Organization as one of the first public information emissaries of the State and remained there for two years. Even after retirement he continued to write books and articles.

Moshe (Teitelman) Tamari's Essays:

"My Hill," (Hebrew), 30.Written as a young man, and published in a 1929 Warsaw newspaper for children, this essay reflects on a special hill near Mlynov that Moshe once thought was Mount Sinai and that remained special to him as he grew up. After leaving the area, he returns to renew his relationship with the hill, only to find men doing work on the area and ruining the magic of the place for the young dreamer. One can see in this early piece of Tamari's writing his literary and reflective side that would persist into his later life. Here he provides a window into a child's view of the world growing up in Mlynov, one that would have to be abandonned under the pressure change and adulthood. Within two years of this essay being published, his hero, Yitzhak Lamdan, would return to Mlynov for a visit that prompts Tamari to write about that experience in a later essay.

"In the presence of Yitzhak Lamdan in Mlynov," (Hebrew), 32-37.

This is a moving and evocative essay that opens up a window into the life of a young boy in Mlynov who aspired to be like his hero, Yitzhak Lamdan. Lamdan was the Mlynov boy who had made aliyah and became famous for writing “Masada”, a poem that crystalized Zionist national identity for several generations of the Yishuv.

Since Lamdan had left Mlynov for Palestine by 1920, in the wake of WWI, young Moshe Teitelman, as he was then called, did not know Lamdan personally before the latter became famous. But Moshe idolized him and describes in this essay how he used to visit Lamdan’s family home in Mlynov and treat it as if it were a kind of holy shrine.

The essay tells the endearing story of a visit by Lamdan to Mlynov in 1931 as seen through the eyes of this young boy who aspires to be a writer and who is meeting his idol for the first time. Lamdan is not the person he initially expects. With overtones of irony, loss and innocence, and the beauty of the Mlynov landscape, Tamari looks back on that momentous visit from childhood when Lamdan came back to town in 1931.

After reading this essay, it is worth reading the poetry selections from Lamdan in this volume as he imagines how much to censure his real thoughts when he visits with his father. The essay was originally published in “Gilyonot” in memory of Yitzhak Lamdan, Chesvan-Kislev, 5715 [1954].

Notes

[8] I want to thank Moshe Tamari's daughter, Ziva Dar, and great-grandson, Yoav Schwartz, for sharing with me their reflections on Moshe's life. ↩

***

Sonia and Mendel Teitelman (also called "S. M. T."), Haifa

Sonia and Mendel Menachem Teitelman were among a number of Shoah survivors from the Teitelman family and the most prolific contributors to the Memorial volume. They sometimes wrote in this volume under the pen name, "S. M. T" and contributed many essays to this volume recalling daily social life and politics in the two shtetls before the War.

Mendel was born in Mervits, the son of Abraham Teitelman (1850–1922) and Rivka (Halperin), and one of nine siblings, most of whom died in the Shoah.[10] His year of birth is given variously as 1900 and 1905.[11]

Sonia (Gruber) (1900–1980) was Mendel's first cousin. Her mother, Shifra (Teitelman) was the sister of Mendel's father. Shifra had married Yosef (Joseph) Moshe Gruber and had a number of children besides Sonia.[12] The Teitelman and Gruber families were deeply intertwined since Sonia's sister, Rachel (Gruber), also married a Teitelman first cousin, named Nahum. Two sisters were thus married to two first cousins who were first cousins to each other!

Sonia and Mendel lived in Mervits where they had a grocery store. They had no children but remained close with the family of Sonia’s sister, Rachel (Gruber) and her husband, Nahum Teitelman[13] A business relationship Sonia and Mendel had with a customer named Bogdan would ultimately be responsible for saving their lives in the Shoah, a story told by their newphew Asher Teitelman.

Sonia and Mendel spent a significant percentage of the German occupation in a hole dug out under a cowshed dug by the kind-hearted forester named Bogdan. During the day, they stood upright in the hole, which was 2 x 2 meters and approximately the height of a person, and by night they were brought inside and slept above a stove called a "pekalich". Through messengers, they were able to keep track of Sonia's sister, Rachel, and her family and at some point during the occupation, the families was reunited in the crowded pit of Bogdan.

After the Soviet liberation of the area, Sonia and Mendel, along with Rachel, Nahum and a few other Teitelmans who survived made their way back to Mlynov and were present at the ceremony to commemorate those who had been lost. With nothing left in Mlynov to keep them there, they made their way to the displaced person camp, Badgastein, in Austria. After a stay there, they made their way by illegal immigration to Palestine. riveting, first person account which has now been translated to English.

Sonia and Mendel's essays:

"Mlynov–A Kehilla for Mlynov and its Surrounding Shtetlekh," (Yiddish), 16–24.

This essay focuses on the communal political and power structure of the shtetls in which Mlynov served as the hub of the "Kehilla", the word for the legally recognized community entity which governed the surrounding shtetls. Among the shtetls that were part of this Kehilla were Mervits, Ostruzshets, Boromel, Demidovka, and Trovits.

Of interest are the local politics. We learn here about some of the tensions not only between the different shtetls but also between the rabbis who vied for authority. Personal peeves are also evident as in the long-standing grudge by the Rabbi of Mervits against the Rabbi of Mlynov who tried to prevent him from getting his post. Also of note is the statement by Rabbi Gordon, the head rabbi of Mlynov, that seemed to anticipate his death at the hands of the Nazis.

What one has here is an intimate look at the local religious and communal politics and some of the underlying grudges and tensions that animated shtetl life. It seems tame at the moment, perhaps, in light of our own situation in January 2021, as I write this summary.

"Kehilla Mlynov–Mervits: Eradicated," (Yiddish), pp. 42–44.

Here, in this moving, heartfelt essay, Sonia and Mendel crystalize what was lost when the ghetto was liquidated. In their own words: "How can we imagine that the well-trodden footpaths, on which our brothers and sisters walked, covered with sweat and blood, are now overgrown with grass, and that no Jewish feet will ever step there again?! How can we imagine that the dear children, brought up tenderly with great efforts, are no longer there, and will never be there again?!"

Different Times in the Shtetl," (Yiddish), 99–101.

The essays contrasts life in Mervits before and after WWI. Before the War, Mervits was not treated as its own independent town and for a time was subsumed under Olyka. Over time, the town was expected to track its own births and census. Most of the residents were refugees and Sonia and Mendel reflect on how the War impacted the town and the rebuilding after that took place after the War ended.

Sources of Our Existence," (Yiddish), 102–106.

Sonia and Mendel here reflect on the various ways in which most Jews struggled to make a primitive living and how such efforts became more difficult over time under Polish rule. Topics include taxation, lending, the leasing of land and some of the differences among members of different occupations.

Community Buildings in Mervits," (Yiddish), 108–112.

The authors reflect on the relative importance of building different community structures in Mervits, especially after WWI when the town had to rebuild from scratch.As one might expect, the synagogue was of central importance but was followed by the bathhouse. The essay discusses the how the rebuilding of the synagogue proceeded. In addition, tensions between different Hasidic dynasties lead to the creation of more than one synagogue.

"Days of Celebration in the Shtetl," (Yiddish), 161–166.

A look at how the Jewish holidays were routinely celebrated in the town and some reflections on the religiosity of the shtetl members. The most interesting moments are the personal recollections of deviations from the norm, as when Mendel recalls how his grandfather would pull the beard of Hershl Goldenberg on Simhat Torah, and how a congregation member stood up and yelled "Lies" during a talk of a revisionist speaker from Mizoch during the Stawski-Arlozorov trial.

Joys And Sorrows In Mervits," (Yiddish), 161–166.

Sonia and Mendel focus here on celebrations of life and rituals of death with a particular focus on weddings, engagement and the matchmaking that led up to them. Particularly interesting is the tale appended to the end about a young widow from town who was seduced into conversion by a non-Jewish man and the rukus that took place in town, trying to figure out a way to return her to her faith.

Baking Matzas," (Yiddish), 181–185.

A delightful and moving look at how the baking of matzah was conducted and changed with mechanization when Pesakh Rimer purchased a machine. Includes a sober reflection as well on the dangerous act of baking of matzah after the German occupation, as well as the the last time matzah was baked in Mlynov after the surival of the authors.

Bread and Wood," (Yiddish), 195.

A short reflection on the struggle for basic necessities and the importance of wood in winter and bread for daily sustenance.

Notes

[10] Mendel's siblings were: Ester Gruber? (–1942), Mirel (Teitelman) Schwartz (–1942), Nahman (–1942), Nuta, Yaakov-Yosef, Yehoshua (–1942), and Mamtzi (Teitelman) Genut (1917–1985). ↩