GOING

BACK TO RADUNANENI

1976

by Henry S. Glickman Ph. D.

Thanks

to

Sue Lever (nee Glickman) for the retyping &

editing.

To view photos taken by Dr. Henry Glickman on his

visit, click links: Cemetery

and Views

To navigate back

to this page after viewing the photos, click on the

link adjacent to the photos "Glickman in Family Album"

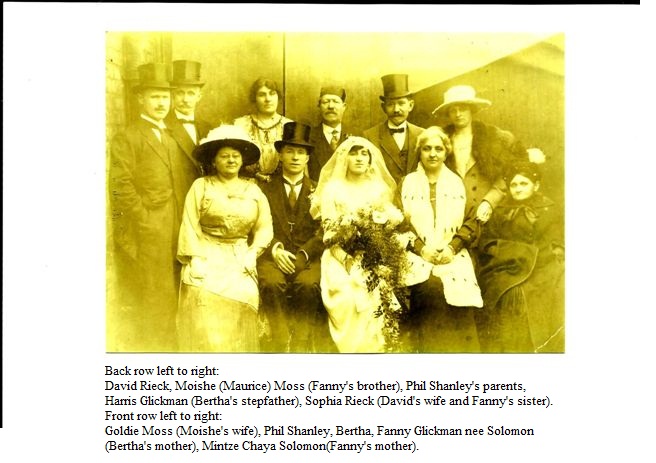

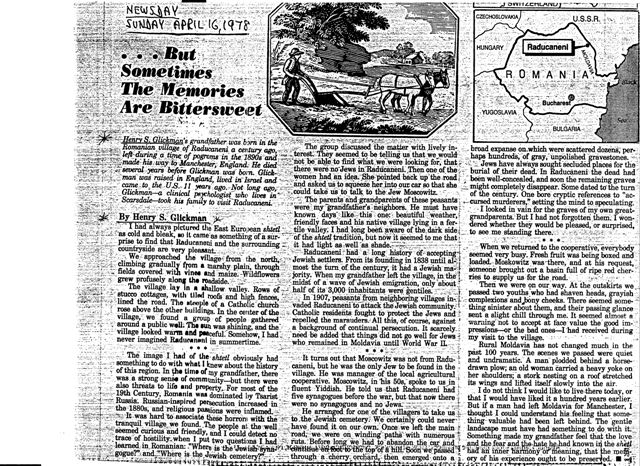

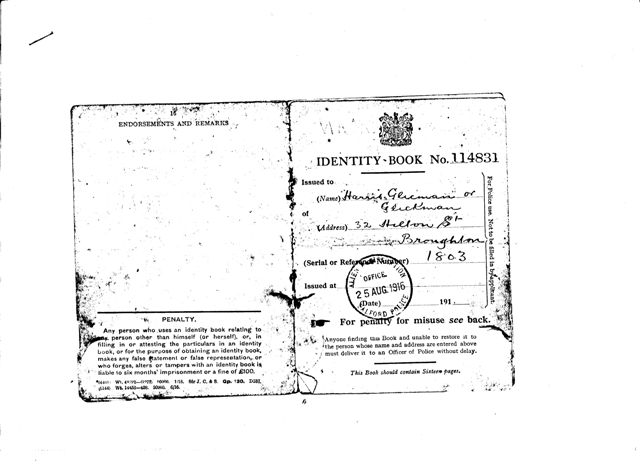

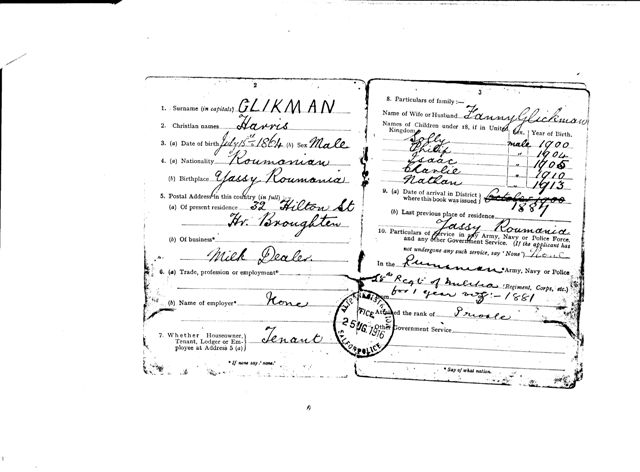

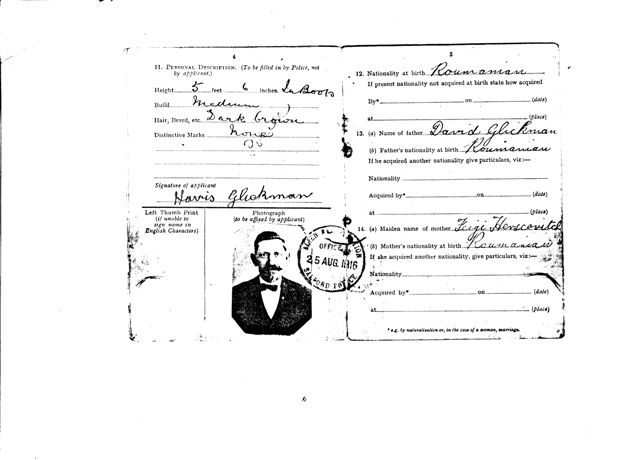

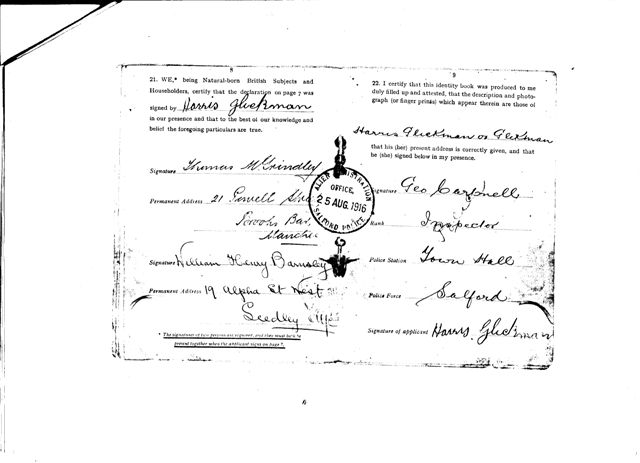

MY GRANDFATHER WAS born in Raducaneni, in the

Moldavian region of Rumania, about 100 years ago. He left

the village in the last decade of the nineteenth century and

made his way to Manchester, England, where he married and

had five sons. He did not prosper economically and died

quite young several years before I was born.

My parents lived in Manchester for a few years

after their marriage, then moved to Glasgow where I was born

and grew up. After finishing secondary school, I spent six

years in Israel and for the past ten years I have been

living in New York. Last summer, I took my wife and two

small children to visit Raducaneni.

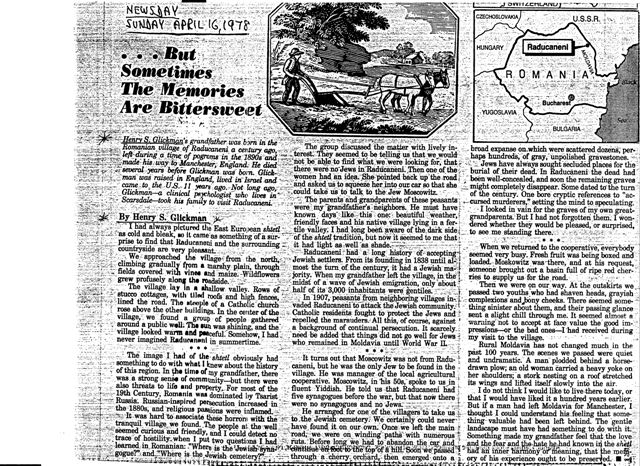

I had always pictured the Eastern European

shtetl as being cold and bleak so it came as something of a

surprise to find that Raducaneni and the surrounding

countryside were very pleasant. We approached the village

from the north, climbing gradually from a marshy plain,

through fields covered with vines and maize. Wild flowers in

a variety of bright colors grew profusely along the

roadside. Then from the top of a rise we came upon the

village, lying in a shallow valley. There were rows of

stucco cottages on both sides of the road, with tiled roofs

and high wooden fences. The steeple of the Catholic church

rose above the other buildings. At first we could see no

movement but when we drove into the village we found a group

of people gathered casually round a public well at the side

of the road. The sun was shining and the village looked warm

and peaceful. Somehow I had never imagined Raducaneni in

summertime.

THE IMAGE I had of what the shtetl looked like

was obviously connected with what I imagined it was like to

live there. I knew that there were people who referred to it

as Der Heim (home) but to me it represented an austere and

confining existence. The danger to life and property was not

the only thing that made living conditions harsh. There were

also the rigors of an implacable religious fervor and a

narrow intellectualism. It is true that there was a strong

sense of community but to me it seemed like the

uncomfortable cohesiveness of people huddling together

against the storm. These cultural traits had survived the

shtetl itself; I had observed them directly in

others and in my own experience I had not fully outgrown

them.

I had never seen a pogrom but the physical

insecurity suffered by my ancestors in Eastern Europe was

vivid in my mind and there was ample historical

documentation. For most of the nineteenth century Rumania

was dominated by Tsarist Russia with its reactionary

Orthodox church. The treaty of Berlin in 1878 recognised the

independence of Rumania on condition that freedom of

religion would be guaranteed for all citizens. But there was

no relief for the Jews. Russian-inspired pogroms and

persecution increased in intensity in the ensuing years and

Jews were officially proclaimed to be aliens subject to

legal discrimination. In 1895, an Anti-Semitic League was

organised with the blessings of the Rumanian government.

Religious passions were inflamed against the Jews in

Moldavia and other regions by the revival of the Blood

Libel.

It was hard to associate these horrors with the

tranquil, rather lethargic village which we found on the day

of our visit. The people at the public well seemed curious

and friendly when we approached them and I could detect no

trace of distrust or hostility when I put the two questions

I had learnt in Rumanian: “Where is the Jewish synagogue?”

and “Where is the Jewish cemetery?” The postman, whom I

approached first, seemed puzzled by my inquiry. He indicated

that he did not know and continued on his way, pushing his

bicycle before him. But the rest of the group discussed the

matter among themselves with lively interest. They seemed to

be telling us that we would not be able to find what we were

looking for, that there were no Jews in Raducaneni. They

were open-faced, genial people who were obviously trying to

be helpful. Then one of the women suddenly had an idea. She

pointed back up the road and asked us to squeeze her into

our car so that she could take us to talk to the Jew

Moskowitz.

The parents and grandparents of this woman were

my grandfather’s neighbors. He must have known days like

this one: beautiful weather, friendly faces and his native

village lying in a fertile valley. I had long been aware of

the dark side of the shtetl tradition and how it had

influenced my view of the world. But now it seemed to me

that the shtetl and its tradition had light as well as shade

which should, perhaps, have been obvious from the start.

THERE WAS HISTORICAL support for such a

view. In the early nineteenth century the Hussite Protestant

church in Moldavia welcomed and protected Jewish residents,

many of whom came from neighboring Bessarabia. Jewish

doctors and merchants were prosperous and highly esteemed;

Jewish schools were established reflecting different shades

of orthodoxy. Raducaneni itself had a long history of

accepting Jewish settlers. It was founded in 1838 and almost

until the end of the century had a Jewish majority. At the

time my grandfather left the village, in the midst of a wave

of Jewish emigration, only about half of its 3,000

inhabitants were gentiles. In 1907, during a local uprising

against the government, peasants from neighboring villages

invaded Raducaneni to attack and plunder the Jewish

community. The Roman Catholic inhabitants fought back to

protect the Jews and succeeded in repelling the marauders.

All this, of course, against a background of continual

persecution; and it scarcely needs to be added that things

did not go well for the Jews who remained in Moldovia until

the Second World War. But the promise and the possibility of

acceptance by the gentiles, or by some of them, was a

persistent feature of the Jewish experience.

Nor was this ambiguity, and the ambivalence it

produced, entirely alien to my own personal experience. I

knew what it was to be an outsider looking wistfully in. I

knew the yearning for acceptance and belonging and its

obverse, a defiant pride in being different. And it went

beyond relations with gentiles. I was an outsider in Israel,

too (which did not prevent me from developing bonds of

affection for the country and its people). One can always

find a minority with which one can identify oneself. I had

detected an interesting kind of figure-ground reversal in my

social perceptions. When reading the New York times, for

example, I sometimes felt mildly self-conscious about being

a British citizen and I found myself hoping that the paper

would speak well of my country; but when I was with other

British citizens I might feel a little defensive about

subscribing to the New York Times and hope the others would

give the paper their approval. Being Jewish was, indeed, a

state of mind.

IT TURNED OUT that Moskowitz was not from

Raducaneni at all but he was the only Jew who could be found

in the village. He was the manager of the local agricultural

cooperative which appeared to be responsible for the

gathering and marketing of all the produce of the village.

Moskowitz was a man in his fifties, dressed much like the

other employees around him. He spoke to us in fluent

Yiddish. Raducaneni, he told us, had five synagogues before

the war but now there were no synagogues and no Jews.

As Moskowitz recalled it, conditions were difficult in the

old days and men had to live by their wits, which suited

some of them very well and went hard with many others.

Moskowitz arranged for one of the villagers to

take us to the Jewish cemetery. We certainly could never

have found it on our own. Only the main road running through

the centre of the village was paved; once we left it we were

on winding mud paths interspersed with numerous ruts and

bumps. We yielded the right of way to geese, hens and pigs

wandering freely between the cottages. Finally, we left the

residential part of the village and started up a steep

narrow path between cultivated fields. Before long we had to

abandon the car and continue on foot to the top of the hill.

It seemed like a strenuous journey for a funeral cortege.

Looking back, we could see the whole village stretched out

before us.

An abandoned concrete building at the edge of a

field marked the entrance to the cemetery. The field itself

was covered with the long green leaves of a maize crop and

showed no sign of graves. Beyond it we passed through a

cherry orchard, then emerged into a broad expanse across

which were scattered dozens, perhaps hundreds, of grey

unpolished gravestones. The terrain was irregular. Parts of

the area were planted with maize, other parts with grass and

weeds; and there was a group of men with scythes who seemed

to be clearing one section for cultivation. From where we

stood, in the midst of the gravestones, the village was

completely hidden from view. Rolling farm country surrounded

us on all sides.

Jews have always sought secluded, private

places for the burial of their dead. It is as if they were

aware of how the dead can interfere and wished to be given a

chance to take a fresh look at their problems and deal with

them in their own way. It is not for the dead, says a

Talmudic dictum, to contradict the living. They are not

entitled to do so, but the Jews know that it happens every

day. In Raducaneni the dead had been well concealed

and soon the remaining graves might completely disappear; I

looked in vain for the graves of my own great-grandparents.

But I had not forgotten them. I wondered whether they would

be pleased, or surprised, if they could see me standing

there amongst them.

WE SAW GRAVES dating back to the turn of the

century and some as late as the 1950s. Most were simple

things, identifying only the first name of the deceased and

the first name of his or her father; they were written in

Hebrew, occasionally with a few words in German. A woman

called Zlatteh, the daughter of Meir, who died in 1906, was

described as elderly, chaste and esteemed. A crude

seven-branched candelabra was engraved superficially at the

top of her stone. Other stones were without ornamentation or

expressions of sorrow or praise; simply the fact of death.

Several epitaphs began with a line from Lamentations: “My

eye, my eye, runs down with water.”

A few stones conveyed a greater sense of pride

and prestige. Low relief pilasters and festoons adorned one

of the stones, which was crowned with a star of David. “Here

lies Mr. Meir Jacob son of Israel Zvi of blessed memory,

known as Mr. Altir, an expert ritual slaughterer and

examiner, and a fine cantor, from 5620 to 5665 (1860-1905),

in this town of Raducaneni. May his soul be bound up with

everlasting life.” Mr. Altir, and his cantorial abilities,

must have been well known to my grandfather.

One of the humblest stones was in the shape of

an obelisk. A small stone tablet had been superimposed on it

and the lettering was cramped and uneven. I could not make

out the first name but the inscription said that she was

“the daughter of Samuel Naphtali, killed by accursed

murderers on the fifth of Tammuz 5691 (1931).” The

word “accursed” was bigger than the rest and took up a whole

line. A few feet away was an identical stone whose

inscription recorded the murder of a man who died five days

after the woman. His epitaph did not use the word “accursed”

and ended with an abbreviation meaning: ”His soul is in

Paradise.” The tablets on both stones were completely

filled. It must have been a bitter choice: to bless the dead

or to curse their murderers.

There was no way of knowing from the

gravestones who committed these crimes or why but the Jewish

experience suggests that the perpetrators had a reason. It

might have been their religious enthusiasm or nationalistic

fervor, or a passion for freedom or equality, or rage

against injustice. The precise ideology of the murderers

didn’t matter to the Jews of Raducaneni because they

believed that there was always going to be some cause or

crusade which was impervious to reason and which justified

the killing of Jews. For my part, I did not share the view

that Jews were uniquely persecuted. There was enough

prejudice to go around. But I did retain a fear of and

revulsion for all forms of absolutism and unreasoning

fanaticism. And, unreasonably enough, I sometimes found

myself responding to the intolerance I deplored with angry

intolerance of my own.

WHEN WE RETURNED to the cooperative, everybody

seemed very busy. Fresh fruit was being boxed, loaded and

transported out of the village. Some of the workers came

over to get a better look at us and they impressed me as

being a cheerful, good-natured group of people. The woman

who had first led us to the cooperative was waiting for us

and greeted us warmly. When our ten-month-old baby

began to fret, she picked him up and calmed him by singing

what sounded like a Russian lullaby. Moskowitz was there

too. At his request, someone brought out a basin-full of

ripe red cherries which were poured into a bag to supply us

for the road. We were very pleased by this gesture and the

good feelings seemed to be shared by all the people round

about us.

Then we were on our way, driving slowly back

through the center of the village. At the outskirts there

were two youths on the road who turned round as we

approached. They had shaven heads, greyish complexions and

bony cheeks. There was something sinister about them to my

mind, and their passing glance as we drove by gave me a

slight chill. It was like a warning to me not to accept at

face value the good impressions--- or the bad ones--- which

I had received during my visit to the village. And I

wondered whether generations of threats and uncertainty had

bequeathed to me the suspicion that things, and people,

including myself, were not necessarily what they seemed to

be.

We drove south from Raducaneni along the west

bank of the River Prut which marks the border between

Russian Bessarabia and Moldavia. It was a broad, muddy

river with wooded islands on the middle. We ate the cherries

as we travelled; they were juicy with a pungent, slightly

bitter flavour, which I found very agreeable.

IN THE OLD days, smugglers with family

connections on both sides of the border used to cross the

River Prut with their merchandise. Further north in Polish

Galicia, the Baal Shem Tov, founder of the Hassidic

movement, would repair to the banks of the Prut for solitary

meditation. He taught his disciples to serve the Lord with

joy---an inner, insular joy, which could be achieved by a

community that desensitized itself to the blows and the

blandishments of the outside world.

Rural Moldavia had not changed much in the past

hundred years. The scenes we passed on our journey through

the countryside were quiet and undramatic. A man

plodded behind a horse-drawn plough which he guided

unsteadily across a field. An old woman carried a heavy

wooden yoke across her shoulders, balancing a pail of water

at each end. People stood waiting at a public well with

assorted receptacles for water; there was no queue and

no-one was in a hurry. And a stork which was nesting on the

thatched roof of a cottage stretched its wings and lifted

itself slowly into the air.

I did not think I would like to live there

today, or that I would have liked it a hundred years

earlier. But if a man had left Moldavia for Manchester, I

thought I could understand his feeling that something

valuable had been left behind. The gentle landscape must

have had something to do with it. Something made my

grandfather feel that the love and the fear and the hate he

had known in the shtetl had an inner harmony or meaning and

the memory of his experience ought to be preserved.

|