-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

The Steinberg Family from Mervits (continued...)

***

(return to start of Steinberg story )

Asher Anshel Steinberg (1881–1921) from Mervits married Chaya Malka Lerner (1881–1942). It is unknown if Chaya Malka was related to the Lerner family that was in Mlynov by 1858 and whose offspring Yossel (Joseph) Lerner came to America.

Asher Anshel and Chaya Malka began having children in 1907 when Getzel Steinberg was born. They had a total of seven children, three of whom survived the Shoah. In addition to Getzel (1907–2003), who later became George Steinberg in America, there was Menachem Mendel Steinberg (1909–1998), Bunia Steinberg (married name Upstein) (1913–1995). The four children who did not survive were Faiga Shtivel (1910–1942) with her husband and two children, Tzvi Herschel Steinberg (1913–1942), Eliaykim (Yukal) Steinberg (1915–1942) and Chuna Steinberg (?–1942).

Life Before WWI

We don’t know much about the family of Asher Anshel Steinberg before the 1920s when a tragedy struck the family. We know that Asher Anshel had a sister named Golda who married Gedaliah (George) Preluck in Mervits in 1906. They had five children before 1913, when Gedaliah left and made his way to Providence, Rhode Island. He headed there to join family who was already there. It seems likely Golda knew that by 1911 Clara (Hirsch) Newman from Mlynov had also settled in Providence with her husband Jacob and perhaps the two husbands, who were both peddlers for a time, knew each other. Golda finally joined Gedaliah in Providence in July 1922 when she and two of her children arrived after WWI had ended. She managed to get an emergency US passport from the consulate in Warsaw.

***

A Family Tragedy Strikes

Family life for the Steinberg family in Mervits comes into focus in the 1920s with the recorded memories of Asher Anshel’s daughter, Bunia, whose story is told by her daughter, Shoshana (Upstein) Baruch. After WWI, when the family came back to Mervits after their evacuation durng WWI, Asher Anshel took council with the rabbi about whether to open a butcher shop. The rabbi counseled against it. Ignoring the rabbi’s advice, he opened the butcher shop anyway and things were going well until a disaster struck.

Asher Anshel cut his hand and was taken to the hospital in Dubno. His wound got infected and since penicillin had not yet been discovered he passed away in his forties. Bunia later recalled that she and her siblings were not told about their father’s passing; she only realized what had happened when they came to take his tallit away for the burial ceremony. She began to sob and wouldn’t let go of his tallit.

Asher Anshel’s passing left his widow, Chaya Malka, with seven children and no means of support. We don’t know much about Chaya Malka (Lerner). It seems plausible that she was the sibling of Joseph Abraham Lerner (1866–1954) from Mlynov who migrated to Baltimore in 1913. With their father gone, the Steinberg children had to help with the burden of the family income. Getzel, the oldest son, who was just a teenager at the time, began to work in the grain business, and Bunia, a younger teen at this point, helped with the geese and housework.

Getzel had a knack for business and improved the family’s economic situation with a farm where he raised wheat and hay, cattle and horses. Bunia took over management of the household and brought in a number of innovations: she replaced straw mattresses with modern ones, changed the bedding to white, acquired a radio, an uncommon item at the time, and set up a room for plants. Bunia also regularly traveled to Varkovychi to help her sister, Faiga, who had gotten married by this time to a man named Shoyleh Shtival, had two children, and moved to that town, which was about 33 km (20 mi) from Mlynov.

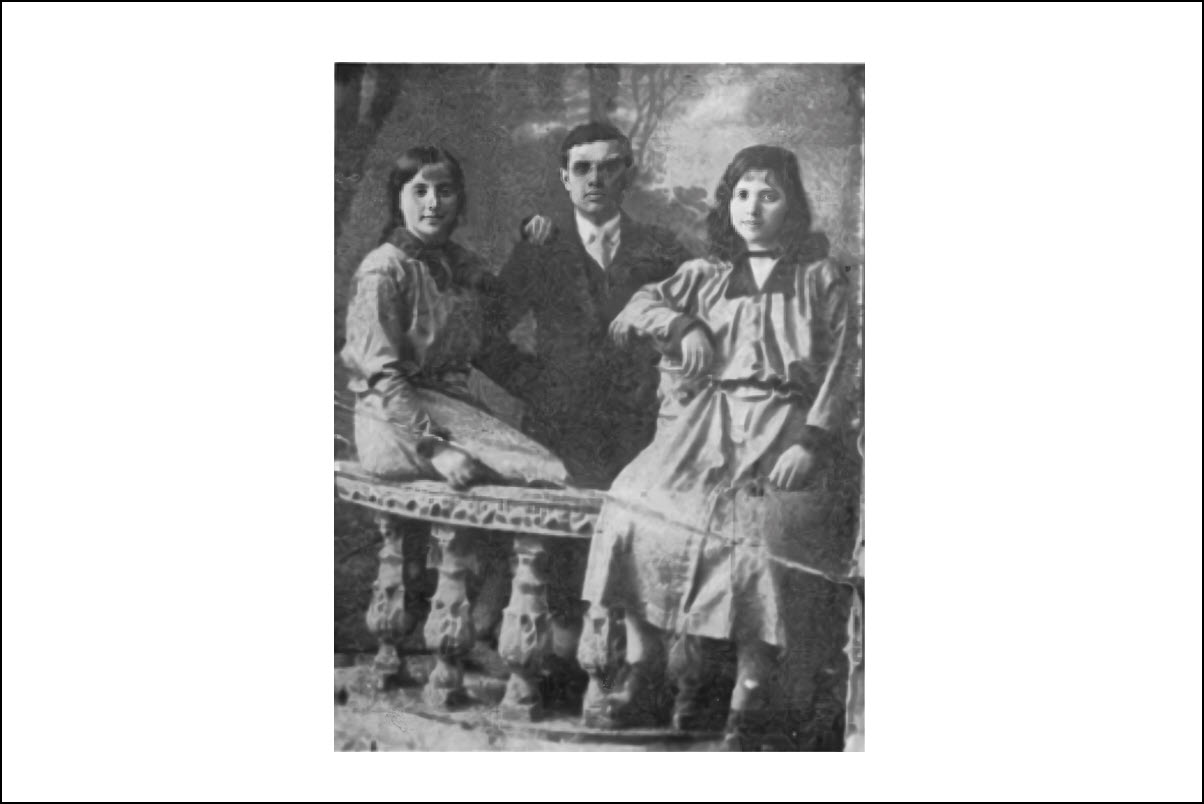

Like many youth living in Mervits and Mlynov under Polish rule in the 1920s and 1930s, Bunia was influenced by the Zionist impulses of the time. She appears in this photo below with other members of the Zionist youth group, Betar, the youth group for Revisionist Zionism started by Ze’ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky Her mother’s home became a center for Zionist social activities and meetings in Mervits. Bunia even went to Dubno and Rovno to hear Jabotinsky’s speeches and she hoped to make aliyah one day.

After her father’s death, Bunia’s grandfather, Eliezer, was guardian of the family, and like some of the other men of that generation in town, he had no sympathy for Zionism and he wanted to get Bunia married. Ignoring the advice of matchmakers, however, Bunia had a secret relationship with a boy named Shmuel, a friend of hers in the youth movement. Bunia never managed to get a British certificate authorizing her aliyah due to her grandfather’s resistance and the need to help her sister’s household, not to mention the increasing difficulty of securing the desired documents. Bunia and her siblings were thus still in Mlynov as WWII began.

***

World War II and Shoah

There is not much information remembered by the Steinberg family about the period starting in September 1939 when the Communists occupied Mlynov and Mervits as part of the agreement with the Germans to split Poland in half. As Bunia’s daughter, Shoshana, explains, the family “did not speak about the Soviet period, because the hardship of that period was minor compared to the Nazi occupation that came afterwards.”

More is known of family’s fate after June 22, 1942 when the Nazis reneged on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact Hitler had brokered with Stalin and attacked the half of Poland held by the Russians. Bunia herself was beaten the first day the Gestapo appeared in Mervits while trying to protect her mother. Her boyfriend Shmuel was among the first ten victims killed on November 7, 1941, when Jewish sabotage was blamed for downed telephone wires, which had been caused accidentally by a Gestapo motorcyclist who never reported the incident. Because of her German skills, Bunia was able to work for a time in a military hospital where she had to do menial work such as polishing the boots of officers and where she sustained regular beatings. But work later gave her authorization to leave the ghetto that would be constructed later, and eventually saved her life.

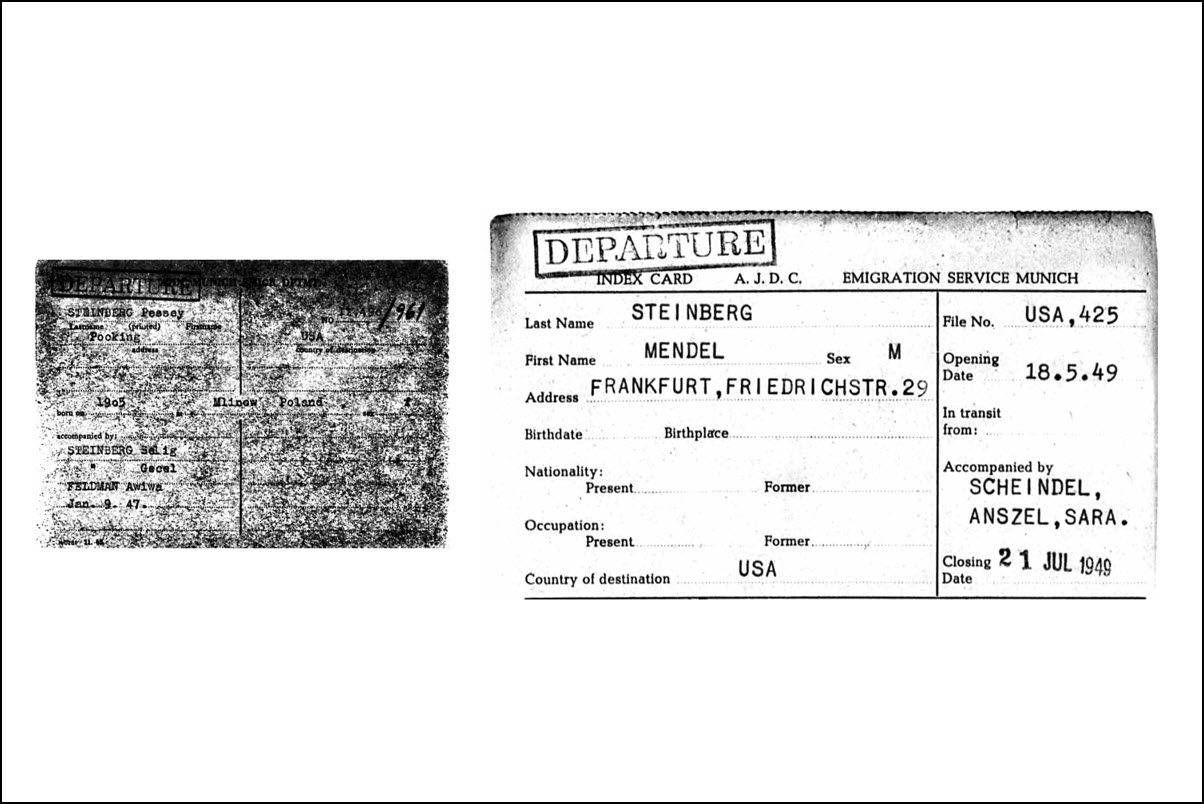

By the beginning of WWII, Bunia’s brother, Getzel, had already married Pesie Wurtzel and they already had a son, Zelig (later Gerry), who was born in 1937 (despite records saying 1939). Pesia's parents were Zelig Wurtzel and Sooreh (Gruber). During the 1930s, Bunia’s brother, Mendel, had fallen in love with a young woman named Sheindel Grenspun, who was from a poor and lower-class family from Trochenbrod. Because Mendel's older sister Faiga had not yet married, Mendel’s mother frowned on the arrangement and so the couple ran off and got married in secret. In 1936 they had a young son, Anshel (later Albert Steinberg), named for Asher Anshel. During the 1930s, Getzel and Mendel continued to build business relationships in the grain business, which ultimately helped saved their lives.

The Mlynov Ghetto

In April 1942, the Mlynov ghetto was set up on two streets in town, Shkolna and Dovinska, and surrounded by barbed wire. All the Jews of Mlynov, Mervits and the surrounding towns were crowded into the two streets of the ghetto on May 22, 1942.

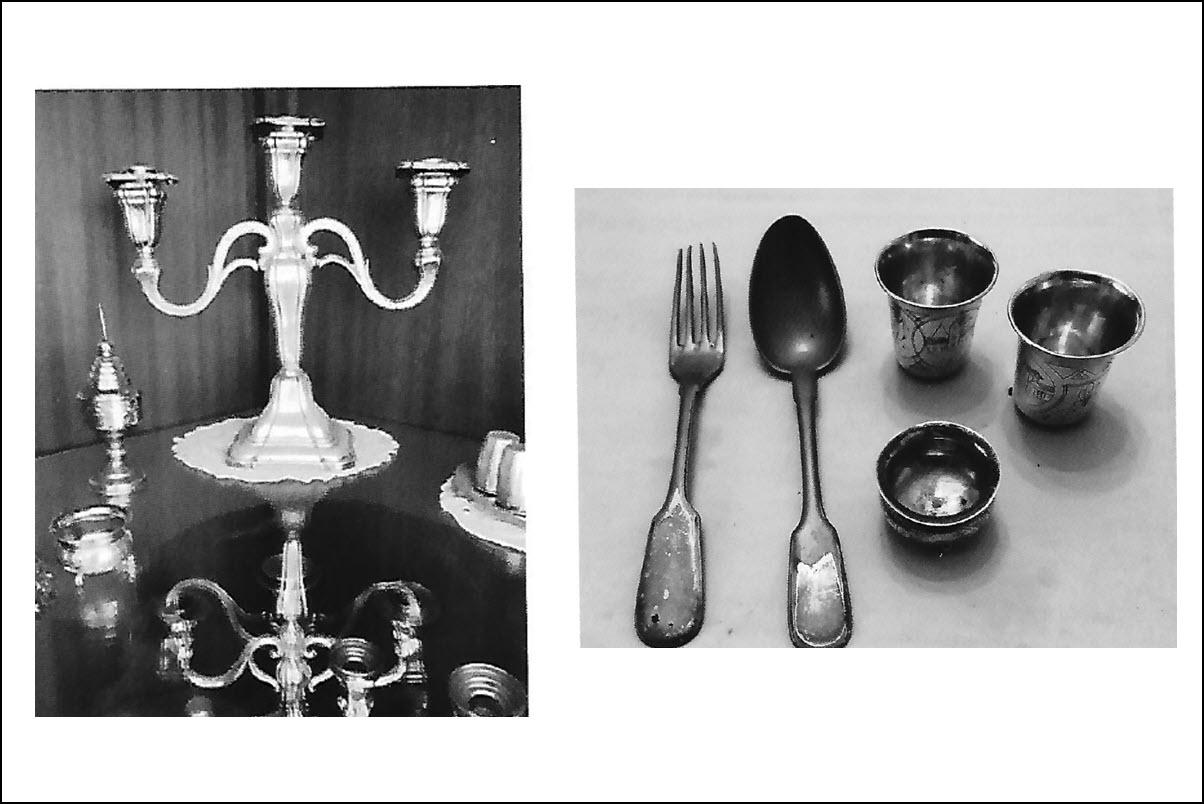

Before going into the ghetto, Bunia, her mother and her sister-in-laws sewed gold coins in their clothing; these coins were critical to the families at a later period when they were looking for people who would hide them. Each family was allowed to bring only a few belongings into the ghetto. Multiple families had to occupy a household together and there were often ten or more living in a single room. In the ghetto, Bunia and her mother lived in one room and Getzel’s family was in the next. Getzel had a position in the Judenrat which occupied the same building. Bunia would only learn after the war that her sister, Faiga and her husband, Falek Shtivel and two children, had perished in the Varkovychi ghetto. The names of their children have not been recovered so far.

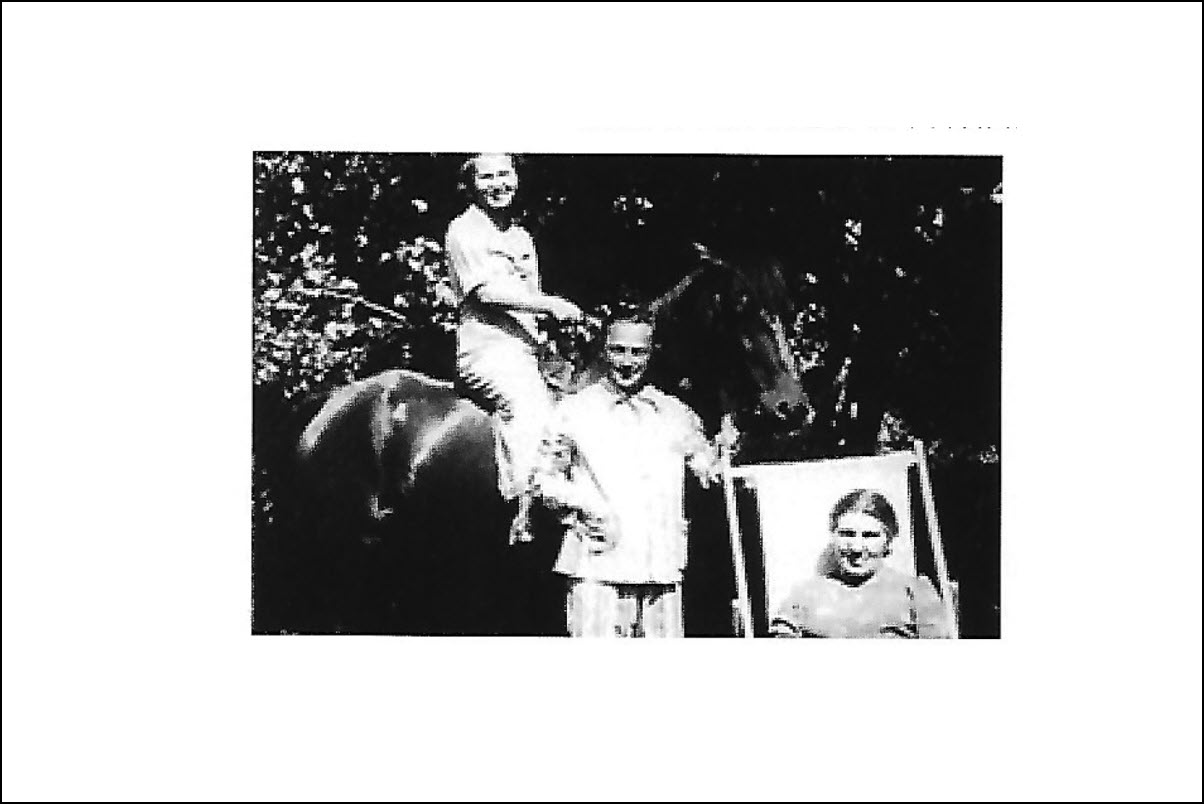

During the time in the ghetto, Bunia became close friends with Neli Feldman, who was married to a first cousin of Getzel's wife Pesia.[1] Even though there was a large age difference between the two women, Bunia and Neli became fast friends. Neli was from a well-to-do family and had grown up on a farm near Rozhyshche, a town on the banks of the Styr in the area of Volyn. A photo of Neli that survived shows her riding her horse which was one of her favorite activities with her mother in the foreground. In 1938, Neli met and married Yosel from Berestchecko and they had a daughter Aviva. Yosel wanted to make aliyah but Neli was not sure she wanted to face the conditions in Palestine. Her sister, Shoshana, had already made aliya in 1936.

Neli had managed to bring some very nice clothes into the ghetto which could be sold for money and food to Ukrainians and Poles who lived nearby. Since Bunia was allowed out of the ghetto for work, she took some risk on herself to sell the clothing on Neli's behalf. After Bunia’s later liberation, she would help rescue Neli’s daughter, Aviva, from the home of a Polish family where she had been left for safekeeping in a story told below. Neli and Yosel unfortunately perished before then.

***

Rumors of the End

Bunia and her brothers each had permits to work outside the ghetto. In September 1942, rumors reached them that local farmers had been given an order to dig a large ditch in the valley called "Kruzhuk," which was between Mlynov and Mervits. Getzel heard that the ditches were for the storage of potatoes, but it quickly became clear that they were intended as graves for the ghetto residents.

After the first day of Sukkot, Bunia recalls her mother running into the fields when the news reached the ghetto that ditches were being dug. Since other ghettos nearby had already been liquidated, they knew what the ditches portended. Both Getzel and Mendel were permitted out of the ghetto for work, so they leveraged their passes and paid gentiles with whom they had business relationships, and managed to sneak their families out of the ghetto to join them. To the astonishment of others, Bunia voluntarily reentered the ghetto feeling some sense of duty and obligation to suffer the fate of other residents.

Not long afterwards, everyone was told to line up in the streets. An older Jew by the name of Hetskel Liber tapped Bunia on the shoulder.

“Bunia, you have papers that allow you to leave the ghetto. Act like you don’t know anything and try to leave. If they question you, show them your documents.” Bunia’s daughter recounts the miraculous way her mother managed to save her life.

She put on a yellow sweater; on the sweater were sewn two yellow Stars of David that the law obligated every Jew to attach. My mother was hoping that they would not see them against the backdrop of the yellow sweater. On her head she put a headscarf and she draped her shoes on her shoulder, like the custom of young Ukrainian girls and she headed towards the exit of the ghetto. The Ukrainian and German guards did not realize she was a Jew and permitted her to leave without bothering her. According to my mother, God blinded their eyes, and perhaps thought she was a shiksa (gentile woman) that by chance happened to be in that place.

***

The Ordeal of Survival

It is extremely difficult to find words to adequately summarize the difficult circumstances the Steinberg and other families faced trying to survive. Bunia, with her brother, Getzel, and his wife Pesia with their young son Zelig, managed to subsist by moving from place to place, relying in part on Getzel’s business connections to find hiding spots. Their young boy, Zelig, often had to be carried and was too young to understand what was going on. Because their benefactors feared for their own lives, Bunia, Getzel and his family were asked to leave their hiding places on more than one occasion, and they took to the forest until the next hiding place could be found. They stayed in crawl spaces under piles of hay, in lofts of granaries, in pits under pigstys, in fields.

One time when they were hiding in under a pile of hay, Zelig cried for food and to go outside to see the sun. Afraid for his own safety, their benefactor, a man named Dmitri, asked them to leave. After some bargaining he finally agreed to allow Bunia to stay. Getzel, Pesia, and Zelig went back on the road again.

After a local priest told the congregation that anyone harboring a Jew would be killed, Dmitri’s wife insisted that Bunia leave as well. Bunia was terrified. She was offered a hiding place with another man if she would pretend to be his wife and cohabitate with him. She was rescued from that paralyzing decision by Getzel who showed up in the morning and had found another hiding place for them together with a Polish man named Sharek whom Getzel paid an exorbitant sum of money. There Getzel and Sharek dug a deep trough under the cow and pig stall.

Mendel’s Family

Meanwhile, Bunia and Getzel’s brother, Mendel, and his wife, Sheindel and son, Anshel, had also sought a place to hide and took the risk to approach a Christian he had done business with by the name of Soldatuk. In his account in the Memorial book, Mendel tells the story of what happened after Soldatuk asked him to leave. Mendel dug a big hole in a potato field on Solatuk's property, where he would put his wife and son, and camouflaged it with wooden logs and above them put soil and potato plants. The family would feed themselves from fruit and potatoes that they found in fields and orchards. Mendel's wife Sheindel had a dream where she was visited by her grandfather, "Motel Tesler" Grenspun, who told her not to leave the place they were hiding and all would be okay. When Soldatuk eventually realized the family was still there, Mendel convinced convinced him based on the dream that they all would be safe. One day when Mendel was looking for water and food, he was seized by Ukrainians and badly beaten. He was left for dead but somehow survived and made it back to the ditch with his family.

Periodically, news would reach Getzel and Bunia of what happened to family. Getzel and Bunia learned that their brother Yukal was murdered along with another twenty Jews who were captured by the Ukrainian commander of Mlynov. News reached Pesia that her family had also been killed. Getzel also heard that his brother, Mendel and family, were murdered by Ukrainians. During this time, Bunia also learned that her friend from the ghetto, Neli Feldman and her husband Yossel, had also been murdered. Before they perished, they had managed to safeguard their 4 year old daughter, Aviva, in the home of a Polish couple in Kivertsi and had told all their relatives where Aviva had been safeguarded. When Getzel was out at night foraging for food one night when he ran into other Jews and learned Aviva had been placed in a gentile home.

One night after news of Neli's death reached them, Bunia was visited in her dreams by the rabbi of Mervits who was holding a Torah scroll written with letters in gold. The rabbi cried out loud, “Bunia choose a letter from this Torah scroll and make a vow starting with this letter.” When she woke up, Bunia related her dream and she vowed “Master of the Universe, I don’t know if I shall survive, but if so, I will rescue the daughter of Yossel Feldman, I will not let her remain in the hands of the gentiles.”

After Their Liberation

At the end of January 1944, Getzel and family joined a number of other Jews from Mervits who had gathered together in a location that has not been identified remembered as Misraka, probably somewhere in the vicinity of Panska Dolina where they had been in hiding. When a man with a bushy beard and long hair arrived there, the people there asked him to identify himself. It was Mendel. He had survived but noone not even his brother recognized him.

The Steinberg family eventually made their way back to Mervits after the Russian liberation and stayed in the house of Rav Gordon who had been murdered early on during the occupation.

After a few weeks of recovery, Bunia set out to fulfill her promise and recover Aviva and traveled to Kivertsi where Aviva had been placed. Though Aviva had met Bunia before the war she did not remember her. Bunia took out a small coat that she found in the Mlynov ghetto which had belonged to Aviva. When she showed it to her, Aviva recognized it, “That’s my coat,” she yelled. After that, she was willing to get closer to Bunia who hugged her and cried. Seeing the emotional reunion, the Polish woman of the house also began crying, but she refused to release Aviva unless Bunia could produce five hundred gold coins.

Unable to meet the demand, Bunia made a plan. The following day, she asked permission from the Polish woman to take Aviva for a small outing to the market to buy her sweets. Aviva was very excited by the opportunity, since in the days of the war, there was much poverty, and barely any food to eat, let alone sweets. Bunia had a coachman waiting in town who had been paid a bottle of vodka to take them to Mlynov. As they passed through a forest on the way, the coachman made an excuse that he was tired and stopped and he made a pass at Bunia who began screaming. Just then a group Soviet soldiers came driving along the road and agreed to take Bunia and Aviva by truck to Mlynov.

Getzel and Pesia were interested in adopting Aviva since they knew they could not have more children of their own and Aviva became part of the family. Aviva acclimated to Getzel and Pesia farily quickly. During the stay with the Polish family, Aviva felt that she didn’t belong to their family. Now, suddenly, she was surrounded by people who knew her parents and grandparents and could tell her about them. Overnight, she went from being a Christian girl to a Jewish one. In the beginning, Aviva used to cross herself every evening before going to sleep and she requested to go to the church like she used to go with her Polish “aunt.” Little by little Aviva was weaned from Christian customs and stopped asking to go to church. She and Zelig became quite close being similar ages.

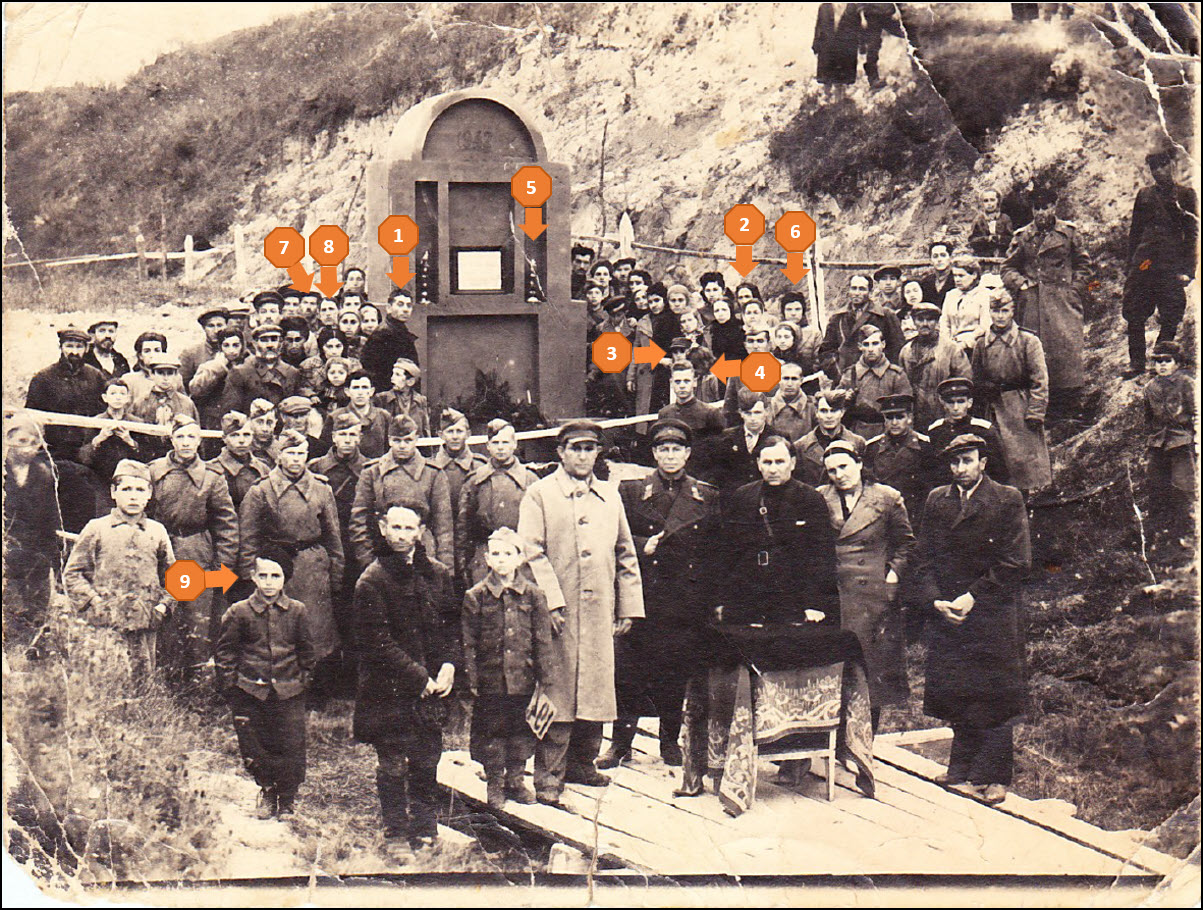

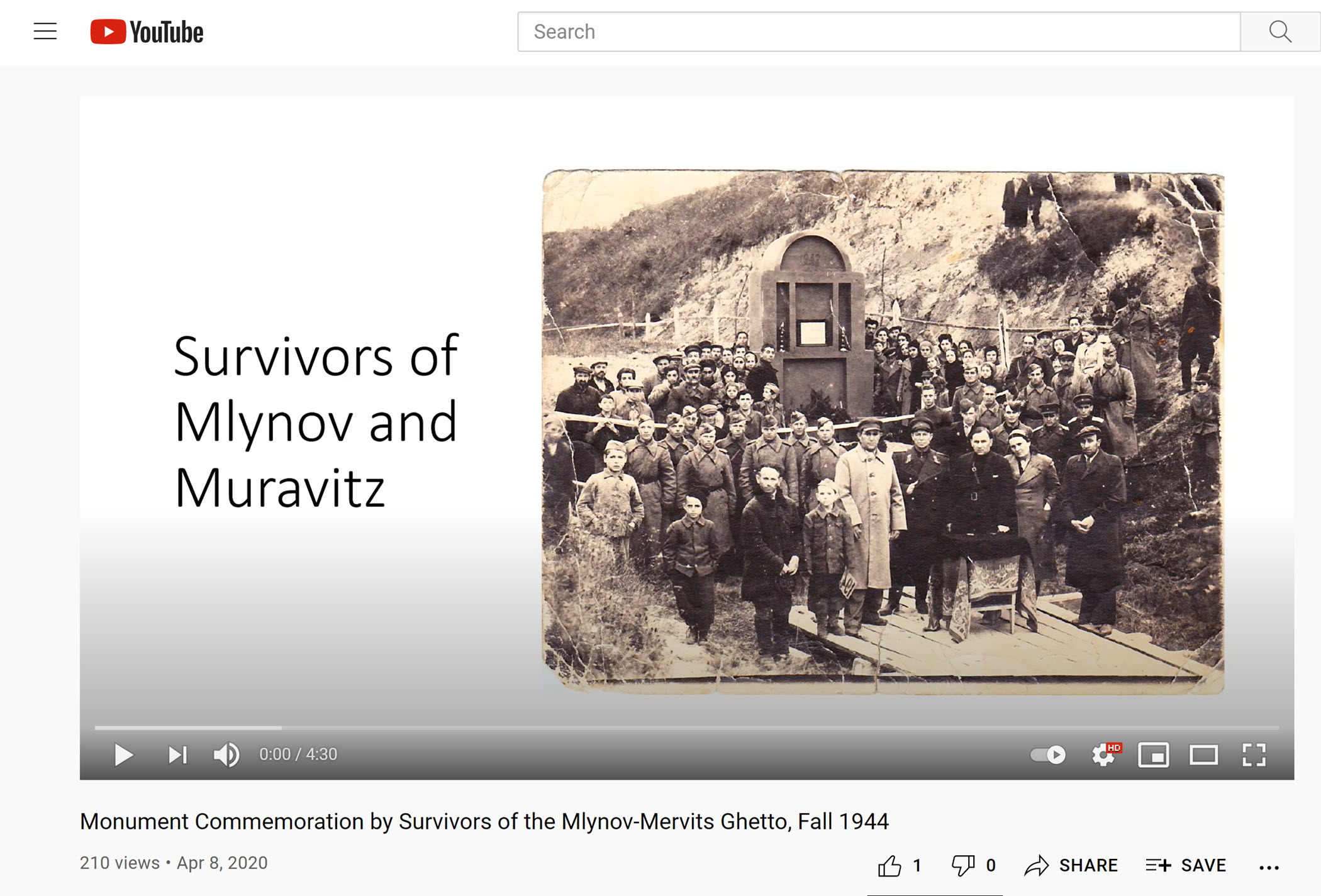

The Memorial Commemoration

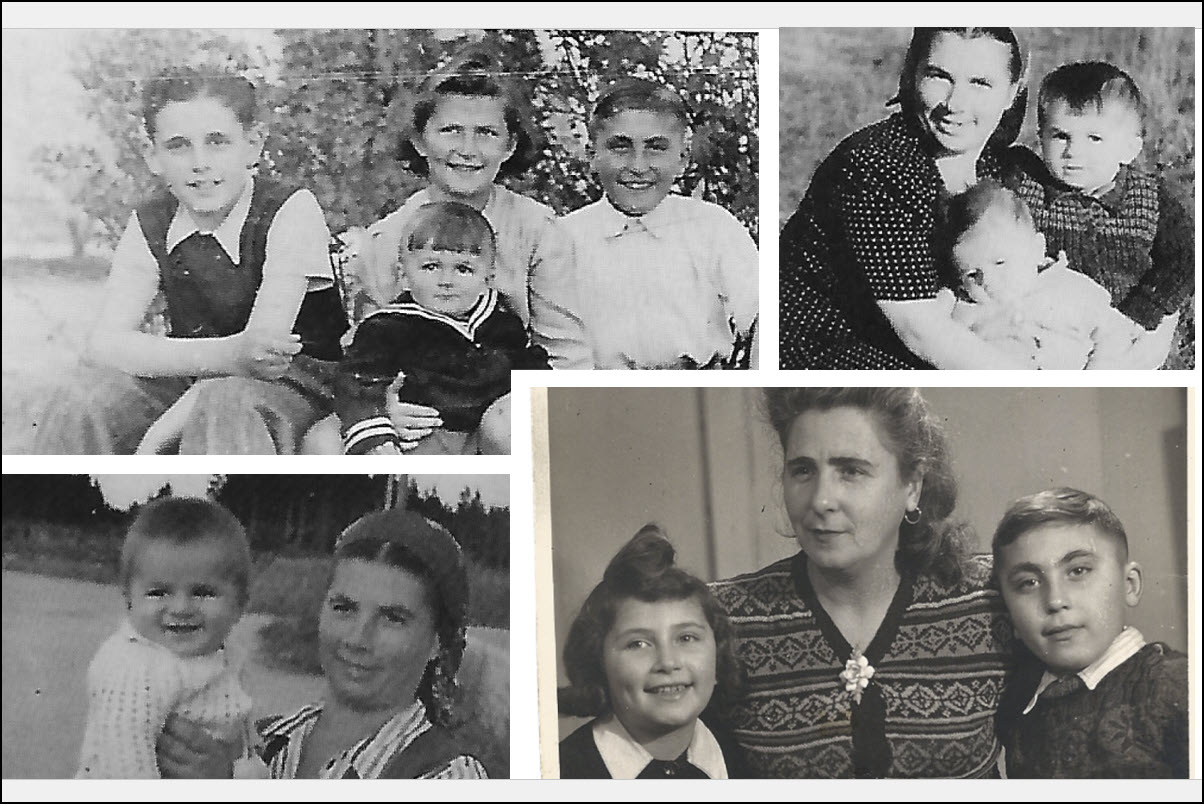

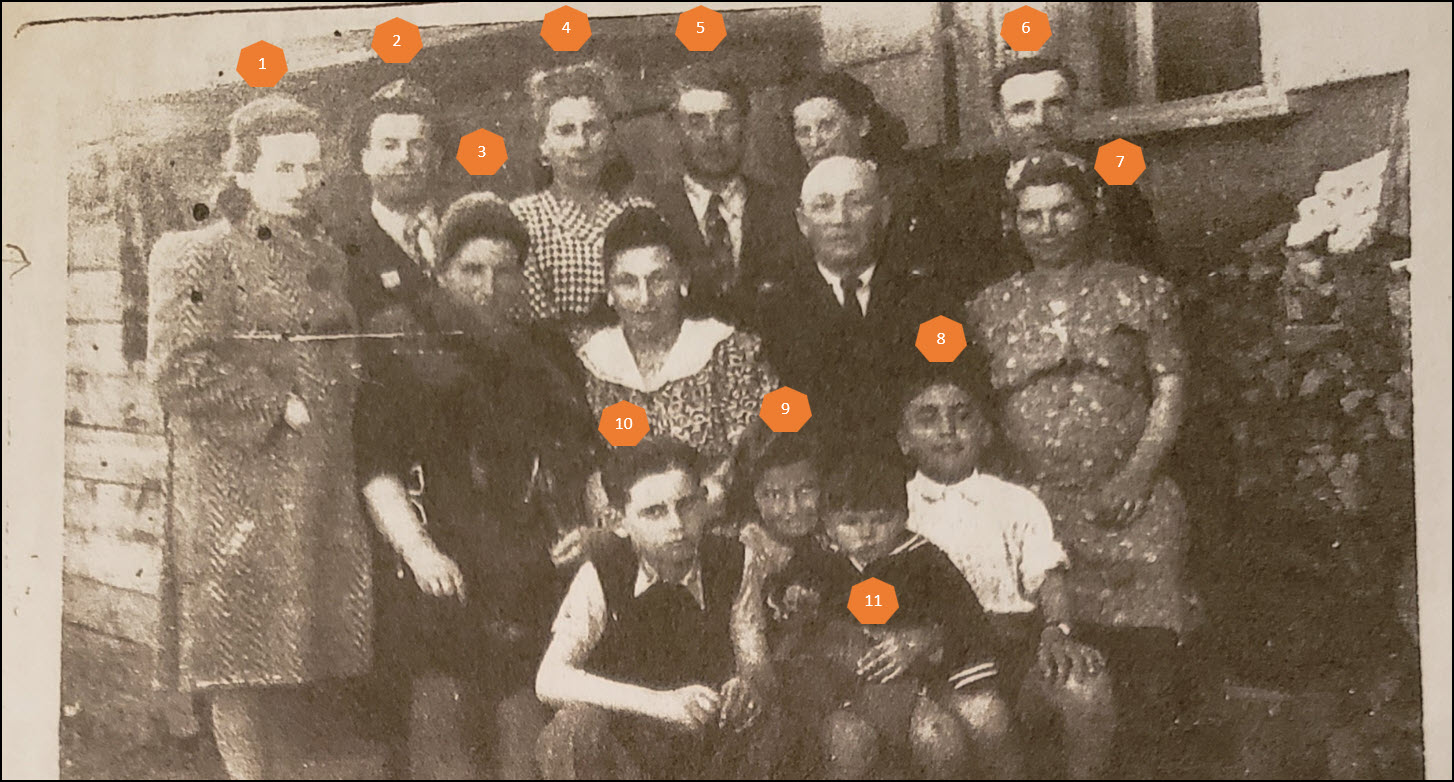

1) Getzel Steinberg, 2) Pesia (Wurtzel) Steinberg, 3) Zelig Steinberg, 4) Aviva (Feldman) Meromi, 5) Pesia's candlesticks recovered from a hiding place 6) Bunia Steinberg 7) Mendel Steinberg, 8) Sheindel (Grenspun) Steinberg, 9) Anshel, son of Mendel and Sheindel

After the Steinbergs returned to Mervits, the survivors decided to erect a memorial to commemorate those who perished, close to the killing pits in the valley of Kruzhuk where the ghetto liquidation had taken place. Getzel was among those who organized the commemoration. Before they stood up the memorial, Bunia told her daughter that they opened up the pit to identify who was buried there. Zelig and Aviva heard about it and went to watch. Aviva was hoping to see her parents and maybe hoping they would emerge alive. Near the killing pit there were scattered pieces of clothes. Aviva looked into the pit, saw the remains of the dead, and she ran away terrified. The sight was shocking, and she remained terrified for a long time.

Yitzhak Upstein Returns

Sometime during this period, Bunia’s future husband, Yitzhak Upstein (1910–2004) arrived back in Mlynov. During WWII, Yitzhak had been conscripted into the Red Army and was kept in Siberia during the War. Yitzhak was one of six children of Hanina Upstein and Raizel. His siblings were: Hana Leah, Batya, Moshe Eliyahu, Baruch Aharon, and Yisrael Yakov. Yitzhak was born after two older sisters and was consequently a pampered son nicknamed “Itzakel,” short for Yitzhak. The family had returned to the town after WWI and had revived a flour store that had been the source of their livelihood before the War. Yitzhak helped with work in the flour store and studied in yeshiva in Mlynov.

Growing up, Yitzhak remembered clowning around and participating in pranks. In cheder, the Rebe would fall asleep while he was reading, and the students seized the opportunity to smear his chair with resin, so that when the Rebe awakened and tried to stand up, he was stuck to his chair and was unable to get up. On one occasion during the Passover Seder, when they reached the section of the Seder when you open the door and say “Pour out your wrath on the nations (“goyim”) who do not know you” (Jer. 10.25), Yitzhak and his friends hid a goat on the other side of the door and the girls were startled and fainted and a doctor had to be called.

His closest friend in Mlynov was Esther from the Fisher family, and they made plans together for the future. Zionist ideas had captured the imagination of his Esther’s siblings and several made aliyah to Israel and settled in the kibbutzim Ramat David and Kinneret. Ester and Yitzhak planned to join them. As Yitzhak grew older, his parents sent him to advanced studies in Rovno. There, he lived with the relatives of his family and studied in yeshiva.

After being conscripted into the Red Army and stationed in Siberia during the War, he committed himself along with other Jewish recruits to observe the mitzvot and avoid eating pork, which was the main stable of the army food. During this period he exchanged letters with Esther and his brother Moishe, but little news reached him about what was happening in the Nazi occupied territories. When Yitzhak finally heard about the fate of the Volhynian Jews towards the end of the War, he deserted from the army and jumped on a freight train headed to Ukraine, making a journey that typically takes three weeks in just three days. He only learned his family's bitter fate when he he arrived back in town. All of his extended family had perished. Feeling profoundly alone, he looked for familiar faces and recognized Bunia and Getzel, whom he knew when they were kids.

***

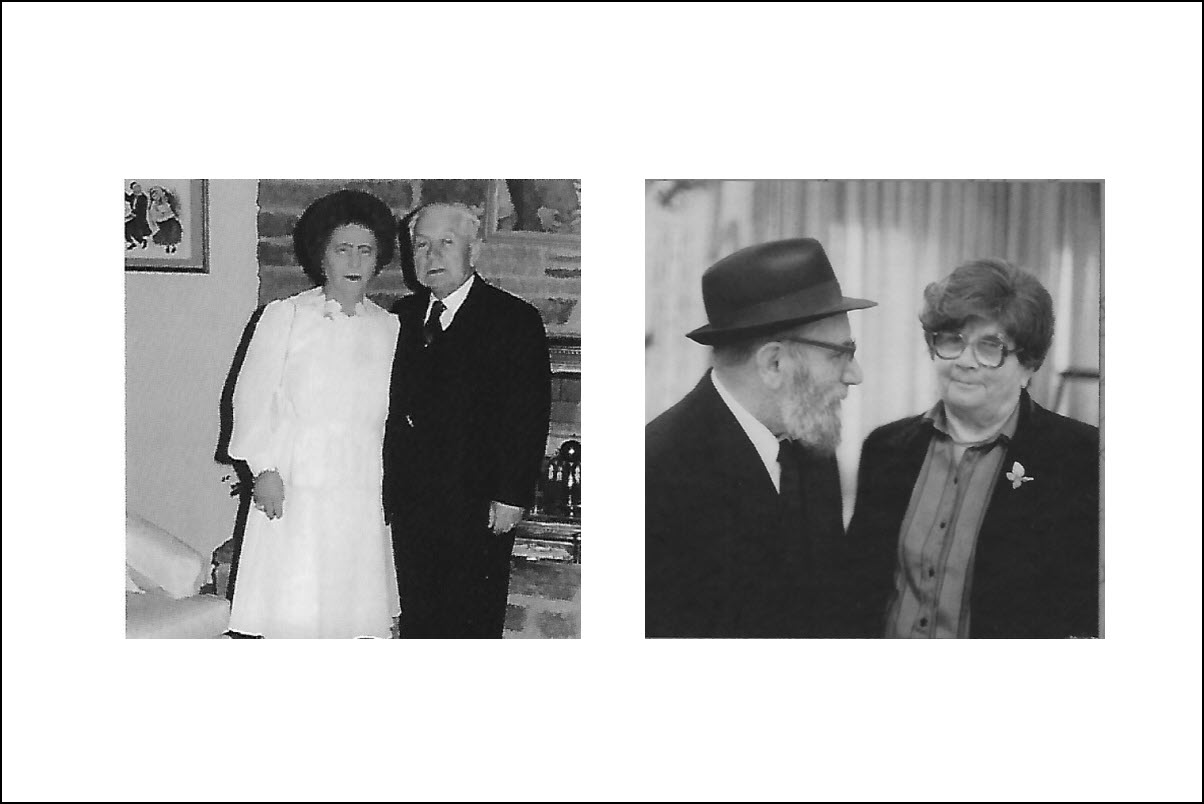

Pocking and After

Realizing there was nothing left for them in Mervits, Bunia, Mendel and Getzel and their families, including the adopted Aviva, made the decision to leave. In 1945, they headed west towards the American held territories in Germany. They had a month long delay in Czechoslovakia. There in the city of Bytom a ketubah was drawn up for Bunia and Yitzhak by Nohum Teitelman, another survivor from Mlynov. The family eventually made their way to the American displaced persons camps. Getzel and his family with Aviva, and Bunia and Yitzhak arrived in the displaced person camp of Pocking, not far from Munich, in Western Germany. Here they began to rehabilitate their lives and make plans for the future. Bunia and Yitzhak got married and would give birth to two sons there. Other Mlynov survivors arrived there as well including Helen Nudler, her two brothers, Yehiel and Moshe, and her father Arke. Liba Tesler and Saul Halpern also made their way there.

In Pocking, most of the Jews in the camps engaged in various activities such as peddling, trade and more. Yitzhak and Bunia were involved in chocolate and Getzel got himself a pair of bicycles and began to work at a place with warm healing springs close to the camp. Zelig and Aviva who were like brother and sister, went together to school, where they met kids of their own age, learned Hebrew and some math.

For reasons not entirely clear, Mendel, Sheindel and their son Anshel ended up in was in another displaced person camp, not far away, though they visited in Pocking and appear in photos with the rest of the Steinberg and Mervits/Mlynov survivors there.

Mlynov survivors among others in Pocking: 1) Liba Tesler 2) Mendel Steinberg 3) Mendel's wife, Sheindel (Grenspun), 4) Pesia (Wurtzel) Steinberg, 5) Getzel Steinberg, 6) Yitzhak Upstein, 7) Bunia (Steinberg) pregnant, 8)Zelig Steinberg, 9) Aviva, 10) Anshel, son of Mendel and Sheindel, 11) Hanina Upstein, son of Yitzhak and Bunia.

Mlynov survivors among others in Pocking: 1) Liba Tesler 2) Mendel Steinberg 3) Mendel's wife, Sheindel (Grenspun), 4) Pesia (Wurtzel) Steinberg, 5) Getzel Steinberg, 6) Yitzhak Upstein, 7) Bunia (Steinberg) pregnant, 8)Zelig Steinberg, 9) Aviva, 10) Anshel, son of Mendel and Sheindel, 11) Hanina Upstein, son of Yitzhak and Bunia.The Future

One of the difficult decisions facing the survivors was where to go to rebuild their lives. Several factors entered into the decision. Mendel and Sheindel decided to immigrate to Cleveland, Ohio where Sheindel's brother had settled. By this point in time, their daughter Sarah (later Susie) had been born in the displaced persons camp.

Bunia's husband, Yitzhak, by contrast, was very religious and he and Bunia made plans to make aliyah. They wanted to live in a Jewish State. The trauma of losing his entire family would make it difficult for Yitzhak to participate in any fun life-giving actvities the rest of his life, though Bunia and Yitzhak did well in Israel and had many grandchildren and many simhas.

In contrast to Yitzhak, Getzel had lost much of his faith through the traumatic experiences. Plus, Getzel felt that the family should “spread its risk” by not locating the whole family in one nation state. So Getzel and Pesia decided to head to the US and made contact with Pesia's relatives living in Springfield, MA. Their names were George and Riko Alman. Riko was a sister of Pesia's mother, Sura (Gruber) Wurtzel. They had been Gedaliah and Rikel Gelman back in Mlynov but become "Alman" in the US. Gedaliah had arrived in the US in 1913 and Rikel and her children had arrived in the US in the early 1920s.

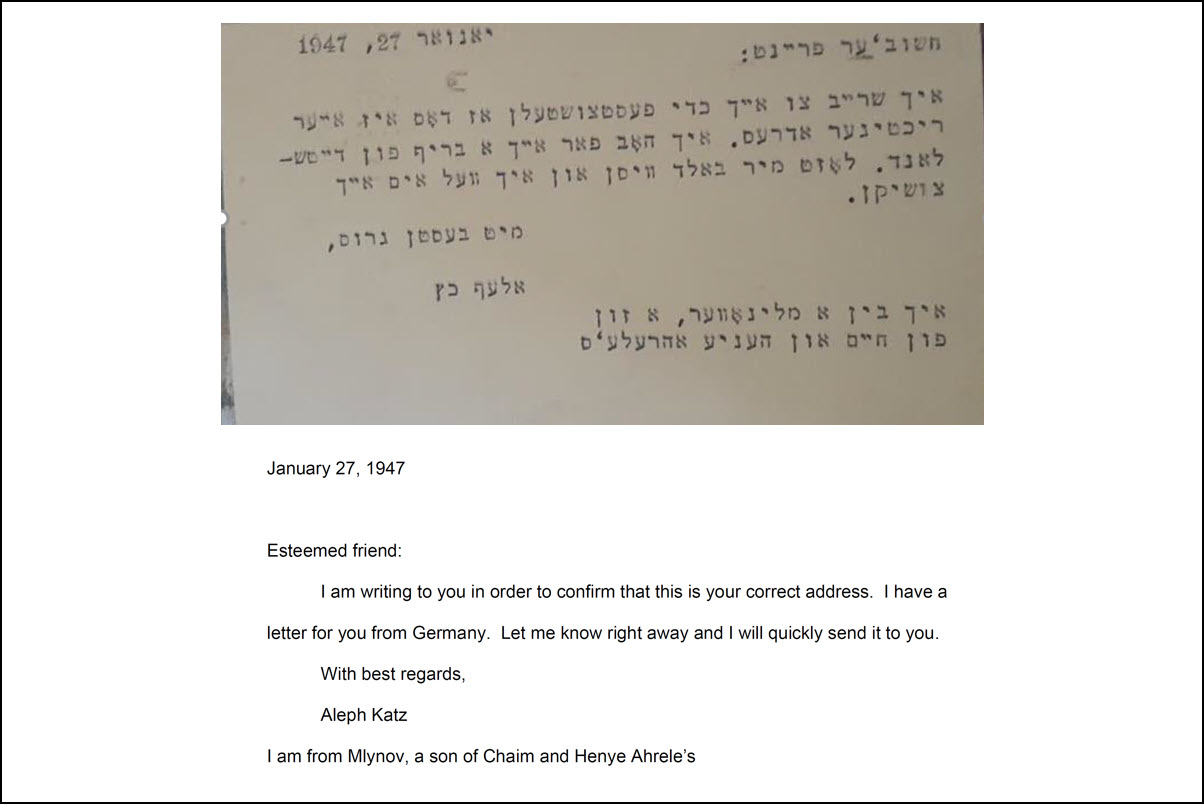

Getzel and Pesia managed to get a letter to their relatives by sending it to Aleph Katz, by then the well-known Yiddish poet, who was working at the time at the Jewish Telegraph Agency (JTA). Aleph Katz tracked down Gedaliah and Rikel's daughter, Bailah, and facilitated a connection.

Getzel and Pesia’s plan had been to legally adopt Aviva and take her with them. However, an aunt of Aviva's (her father's sister), named Shoshana Feldman, had made aliyah in 1936 and had learned that Aviva was still alive. Shoshana was joyous that a remnant of her big family had survived and she saw it as her obligation to bring Aviva to the Land [of Israel] and raise her with her own daughters.

Of course, by this time, Getzel and Pesia had already unofficially adopted Aviva into their family. But Pesia was a religious woman and concluded that it was righteous for Aviva to grow up among her own close family and was willing to release her claim on Aviva, despite raising her as a daughter for several years. Aviva, for her part, wanted to remain with Getzel and Pesia, and in particular with Zelig, who had become like a brother to her. And so Aviva once again lost a family and traveled with Bunia and Yitzhak to Israel when they made aliyah in 1949. Zelig remembered for many years the pain of separation that morning when they woke him up in order to take Aviva away.

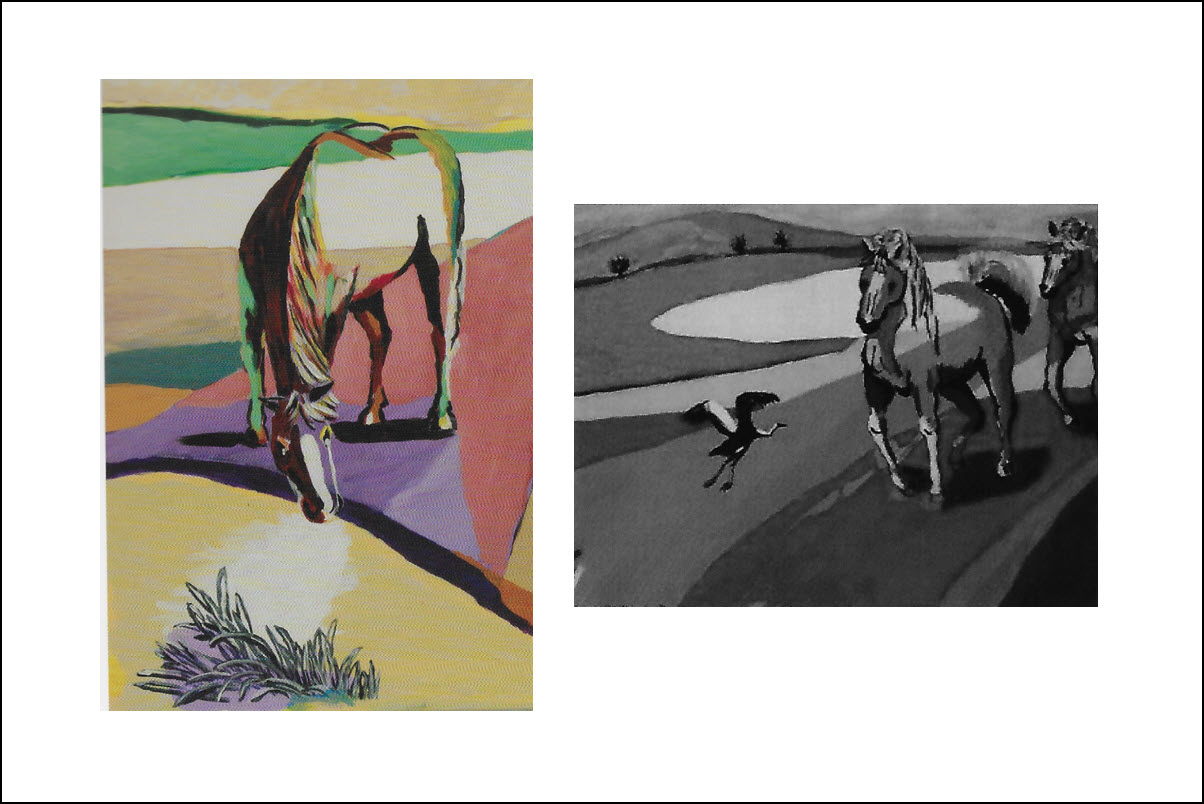

Aviva grew up in Kibbutz Ein Harod. For a long time, she was not able to discuss what had happened to her. Later in life, she stared to draw and paint, especially transparent horses through which one could see background scenery, recalling the photo of her mother on her horse, and providing Aviva a medium through which to engage what happened to her during the darkness of the Shoah.

Further reading

You can return to the beginning of the Steinberg story, download the book length account of the Steinberg story in A Struggle To Survive, watch the interviews with Getzel and Zelig Steinberg, or view the short video about the Memorial commemoration below.

Return to the beginning of the Steinberg story.

- History