-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

. The Nudler Family from Mlynov

***

(return to start of Nudler story )

The Communists Come to Town

After the Russian invasion of Poland in September 1939, Mlynov rapidly fell under Communist rule. A Russian military pilot took over a room in the Nudler house, and Moshe (Morris) remembers him flying his plane low over their property. He and other pilots were stationed at the new airfield recently built just outside of town and they commandeered rooms in the small town. This airfield would later be bombed on the day of the German invasion in June 1941.The Nudlers were not the only ones with a Russian pilot in their home. Other Mlynov survivors, such as Liba Tesler, also recalled Russian pilots stationed with her family during this period and while the Communist takeover created economic suffering for Mlynov's residents, Liba remembered the three pilots who stayed with her family as polite, courteous and friendly. They would bring home cloth for Liba’s mother and candy for Liba and her sister.

The Russian pilot living with the Nudler family advised Arke to leave Mlynov because of the impending war. But as his son Moshe later recalled, Arke wondered how the family could possibly leave their home, livestock and belongings. They were not alone in this thinking.

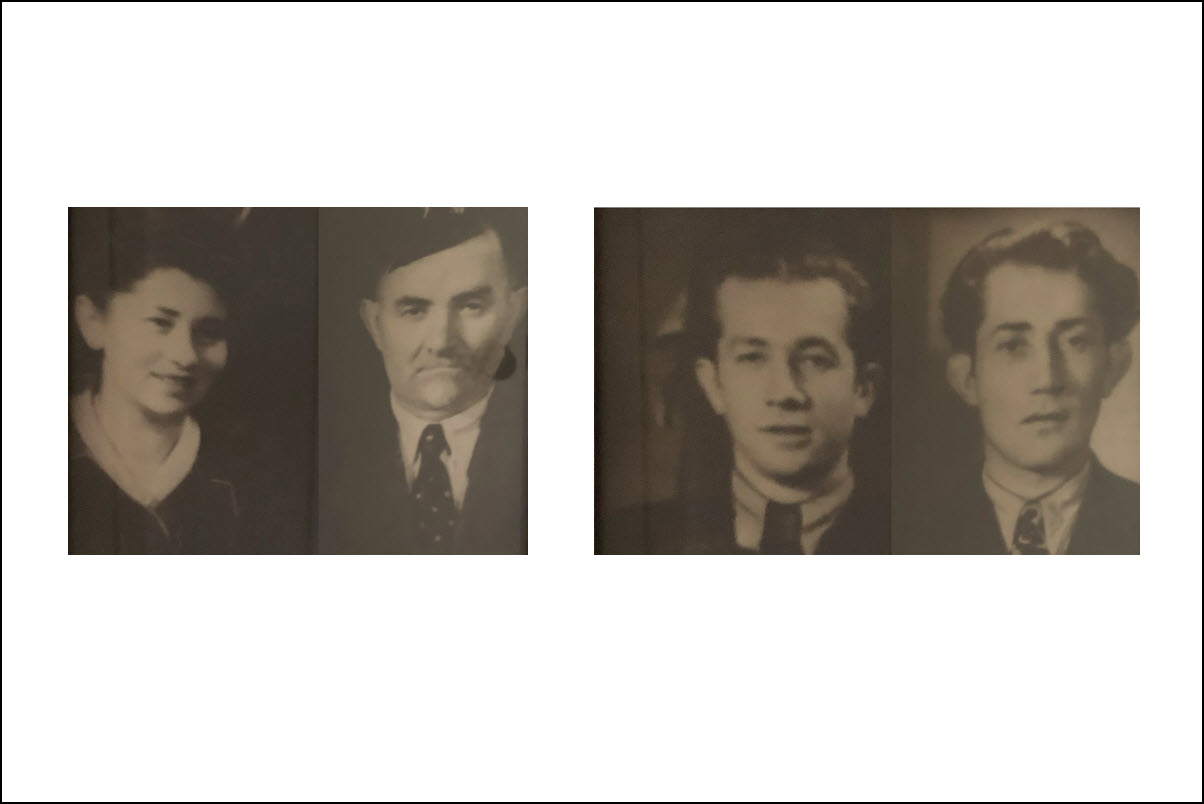

In 1941, not long after the Russian occupation in September, the two older brothers, Yehiel (Harold) and (Moshe) Morris were conscripted into the Russian (Red) army. They did not know it then, but their conscription would save their lives, as it would other young men from Mlynov, such as Yehiel Sherman, and Yitzhak Upstein, who survived fighting with the Russians or shipped off to Siberia. Other Mlynov boys disappeared fighting for the Red Army.

Before Yehiel and Moshe left Mlynov, their uncle Moshe Polishuk (the one in the family photo) advised the brothers to make sure that their army boots fit well, and to bind their feet tight with cloth so they wouldn’t get blisters. The brothers were ordered to walk with their unit first to Mtzensk, Russia, a distance of 962 km (598 miles) and ultimately to the German front at Smolensk. While marching, the men would sing and Morris, who had a good voice, was told to lead the singing. Hungry on the long march, Moshe stole a few loaves of bread from a truck and took milk from a cow. When his superior saw this, he was punished by having to patrol all night.

In general, though, the Nudler boys were conscientious, hardworking, and efficient and army superiors told soldiers in their unit to emulate the examples of the ‘Nudlerov’ boys. Moshe declined an opportunity to become an officer, not wanting to be separated from his brother who was in the same army unit. Sticking together they managed to survive. Moshe who was called “Misha,” felt fortunate that people didn’t identify him as being Jewish, because of his fair complexion. His role was to be runner for the telephones. He was expected to carry the telephone, run as close as possible to enemy lines and report back what he could see through the binoculars. Yehiel followed behind him, carrying the telephone lines. In this way, they were always close together.

Later in life, the brothers recalled being able to see the Germans at the battle of Smolensk, a battle the brothers were fortunate to survive. The first Battle of Smolensk took place during the second phase of “Operation Barbarossa,” the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II. It was fought around the city of Smolensk between 10 July and 10 September 1941, about 400 km (250 mi) west of Moscow. The Germans had advanced 500 km (310 mi) into Russia in the 18 days after the invasion on June 22, 1941. During this time, the Soviet 16th, 19th and the 20th armies were encircled and destroyed just to the east of Smolensk, though many from the 19th and 20th armies managed to escape the pocket. Some historians believe the cost to the Germans during this drawn-out battle, and the delay in the drive towards Moscow, led to the subsequent victory of the Red Army in the Battle of Moscow of December 1941.

How did the brothers survive? Their memory was that suddenly, out of nowhere, orders came to remove all soldiers who were from Ukraine and send them to other units. They later interpreted this reassignment as the result of the defection of a Red Army Ukranian-born general named Andrey Vlasov, which occurred in 1942. Their reassignment may have happened for other reasons. Perhaps it was, as Moshe concluded, that his Russian commander was Jewish, and recognized that the brothers were Jewish as well. Knowing that the upcoming battle would likely be fatal, Moshe felt that the commander released the brothers to save their lives. Yehiel and Moshe joined a working battalion in Gorky. There, they worked in a machine shop by the forest, where they cut trees and worked on the railroad until the end of the war.

***

Back in Mlynov

As the War ended, Yehiel and Moshe returned to Mlynov. They found only their father Arke and sister Ella (Helen) among the living. The brothers would learn that their family had been put into the Mlynov ghetto which was erected on May 22, 1942. When their father Arke heard rumors, as did other families, of the pending ghetto liquidation, the family made an escape from the ghetto one night and somehow slipped through the barbed wire surrounding them. With nowhere to go, they made their way to the forest outside the nearby village of Smordva where they heard about other Jews hiding in the area. There, they hid in bunkers along with twelve others. Other Mlynov families were also hiding in the Smordva forest such as the Teitelmans who also survived the war.The Nudlers lived there in the Smordva forest for about two years, with no warm clothes and little food, except that which they were able to scounge from farms or fields at nighttime. At times, the young Helen recalls being sent out at night to bring back food for the family.

One day, the Ukrainian collaborators learned of the bunker’s whereabouts and began shooting, as the family fled in different directions. Helen never saw her mother, younger brother and sister again. All three were shot and killed. According to a report by Soviet Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK) which investigated the atrocities of the Nazis and their collaborators, "on December 29, 1942, 25 [Jews] including Mrs. Nudler and [her] two children of 11 or 12 were shot to death by Gestapo men in the 7th section of the Smordwa Forest."

A first hand memory is provided by David Berenstein who was also hiding and escaped:

… When I was hiding in the Smordwa Forest, there were there also 120 Jews who had been hiding from the Germans. On December 29, 1942, the Germans, together with the [Ukrainian auxiliary] police of Mlynów Region, carried out a search and [as a result] 25 [Jews] were shot to death by the Germans and [Ukrainian auxiliary] police in the 7th section of the Smordwa Forest. However, I escaped from there. From [former] residents of the town of Mlynów I learned that Mrs. Nudler and her two children of about 11 and 12 had been shot to death. My father and I were also caught by the [Ukrainian auxiliary] police, and we were taken to be shot. I was beaten and then [my hands] were tied. When we were being taken through the [Smordwa] forest, my father untied my hands and threw sand into the policeman's eyes. Then I started to run, but my father was killed on the spot, I was wounded but, due to the fact that it was dark, I succeeded in hiding in the forest. I was also an eyewitness of the event when, on December 29, 1942, the Germans caught a 5-year-old boy in the Smordwa Forest and despite the fact that the boy pleaded for mercy and kissed the hands of the Germans, the German soldiers tore off his arms and then shot him to death. When I and some friends went to bury the bodies [of the shooting victims], we could see that the majority [of the victims] had been shot in the head.

Etka (Helen) and her father had run in different directions when they were discovered but later found each other. Etka, still a young girl, had to tend to her father who had been shot and wounded during flight. Partisans later found them and assisted. Living life on the run, Etka tended to her father and they eventually snuck into a stable where they hid in a haystack for about eight months. The farmer’s wife, a Czech woman, spotted them and would drop off food when her husband was not around. This saved Helen and her father’s life.After the War in Mlynov and Pocking

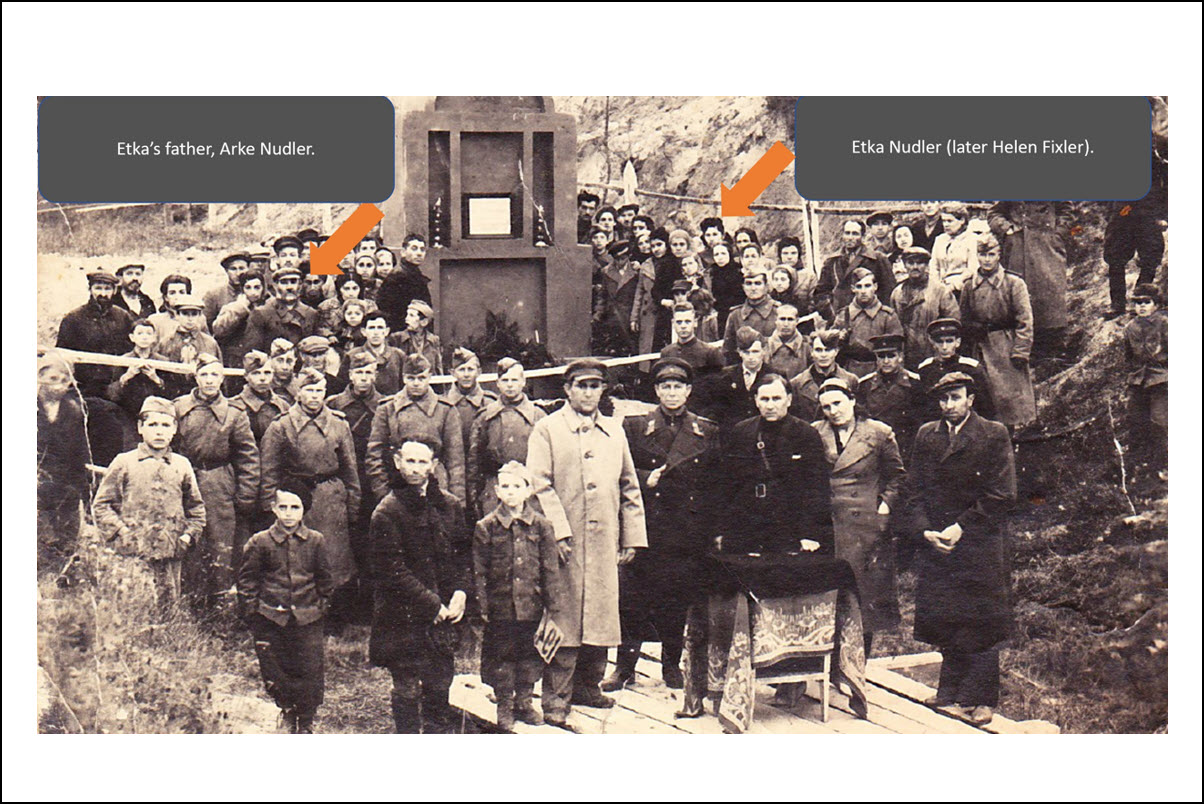

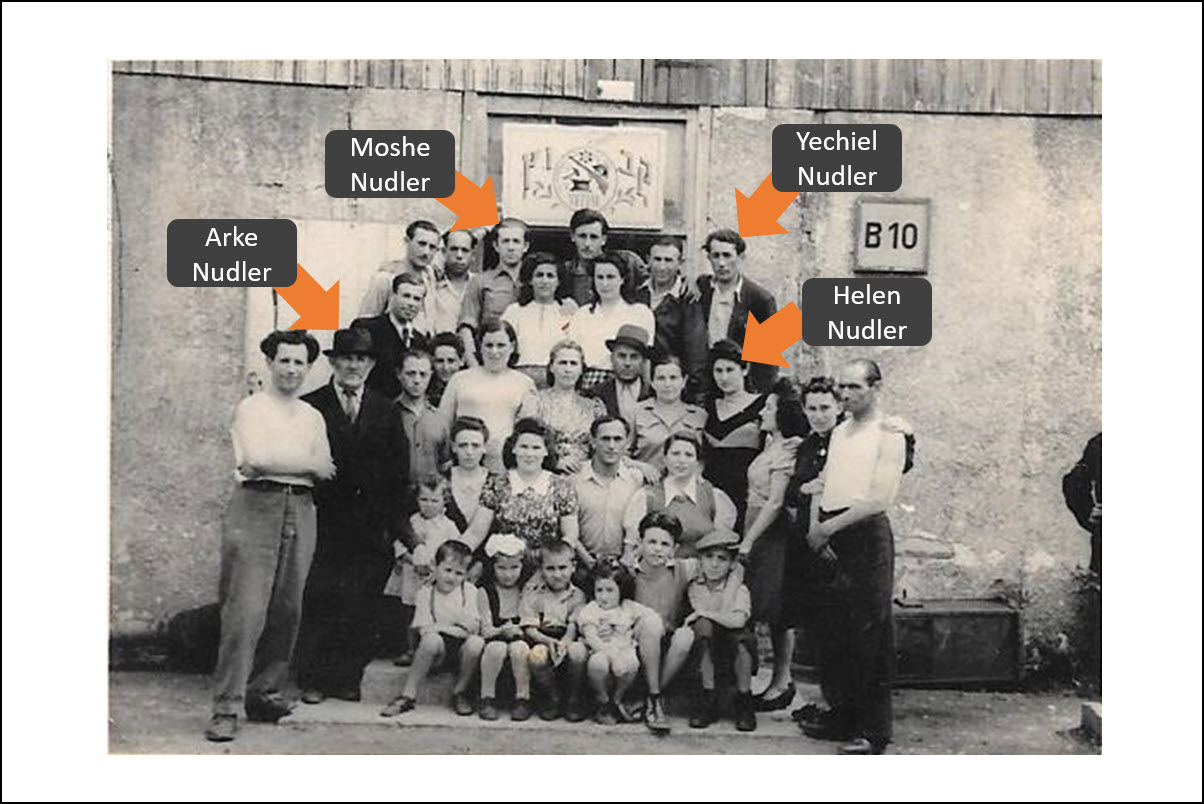

When the Red Army arrived, Helen and her father came out of hiding and returned to Mlynov for a month, where they were reunited with other survivors. They were there at a commemoration event that took place where the liquidation of the Mlynov ghetto had occurred.Realizing there was nothing left for them in Mlynov, the family was paid an American a great deal of money to get them to the Pocking Displaced Persons camp in Germany which was under American control. About 600 Jews were crowded on a train that passed through Czechoslovakia. As they arrived near Prague, the Czechs stopped the train and announced that they were to be sent back to Poland, where they knew they could be killed. When the passengers refused they were unloaded and put into barracks for a several month wait. Moshe, Yehiel, Etka and Arke were eventually transferred to Pocking, Germany, where they lived in the Pocking Displaced Person (DP) camp for three years, from 1945–48. They were there with other Mlynov survivors, including the Steinberg family and Liba Tesler.

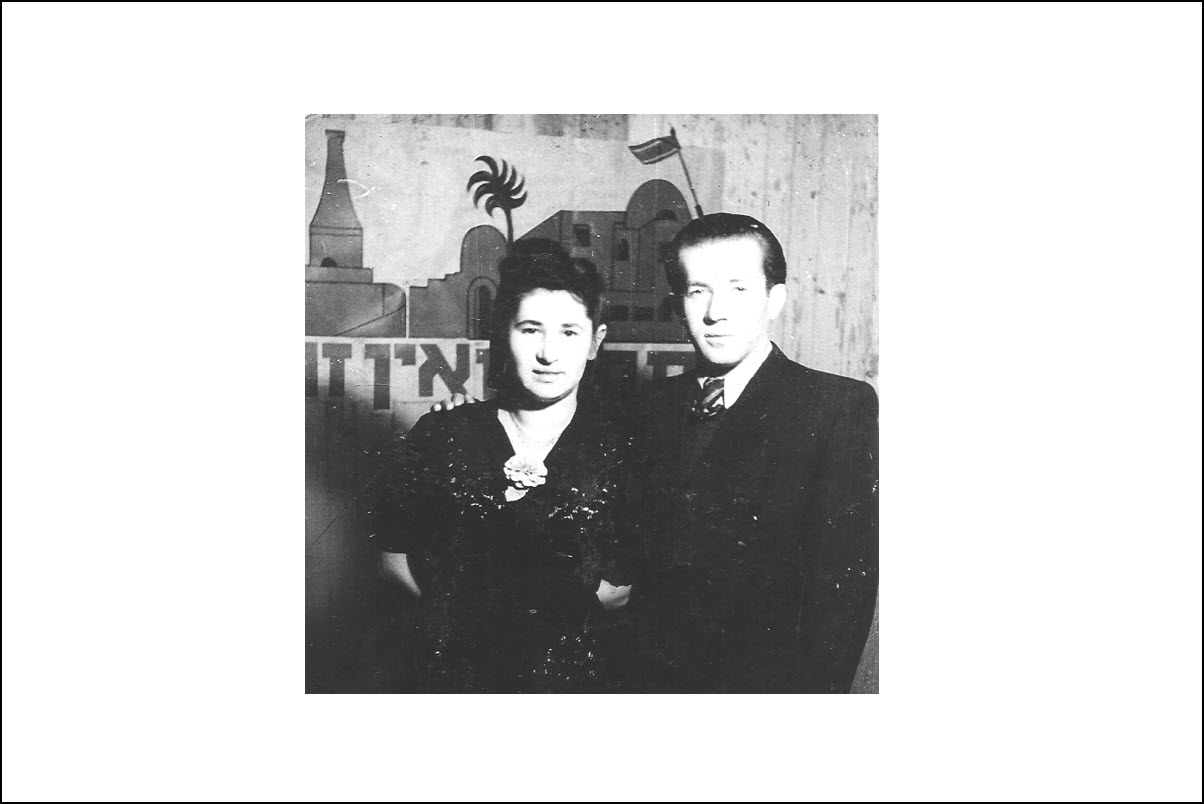

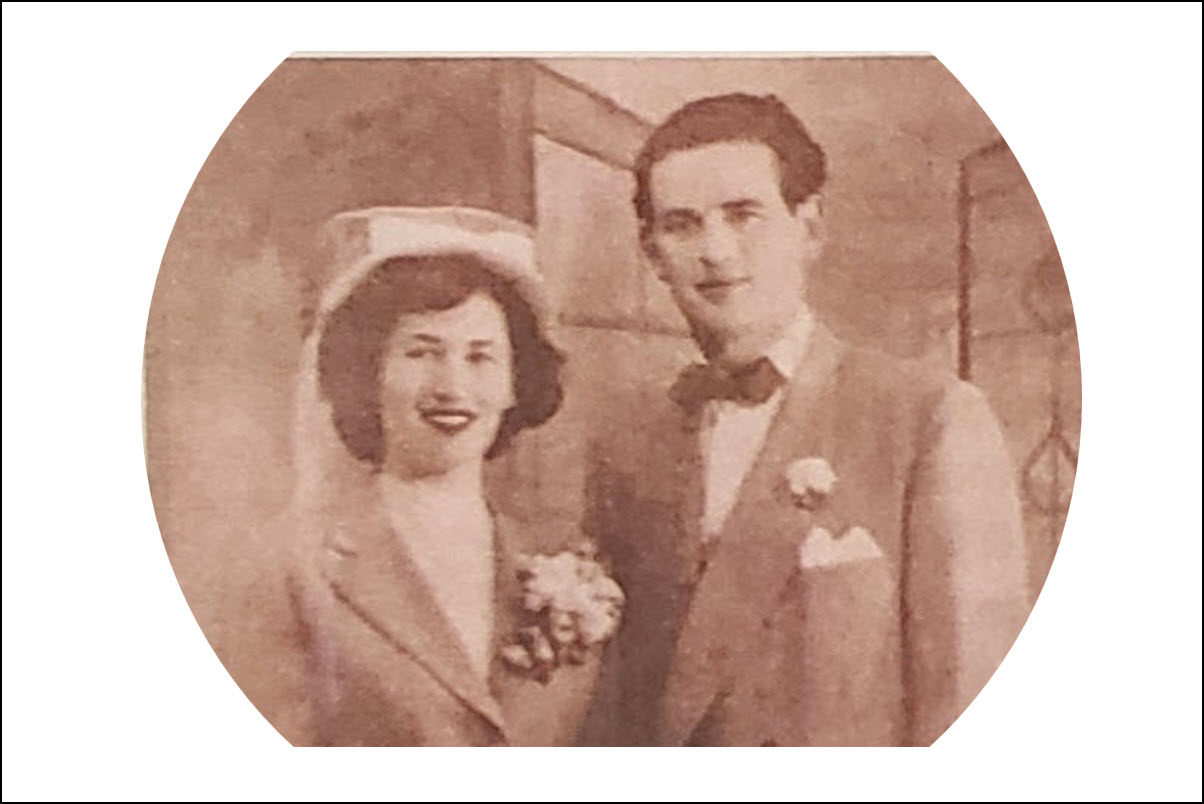

In the DP camp, refugees slept in barracks, and received food rations from United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (“UNRA”). In Pocking, Harold met Misia and they married there on October 22, 1947. Their son Aron (Harry) was born on Jan 1, 1949 in the camp.

Heading to the US and Canada

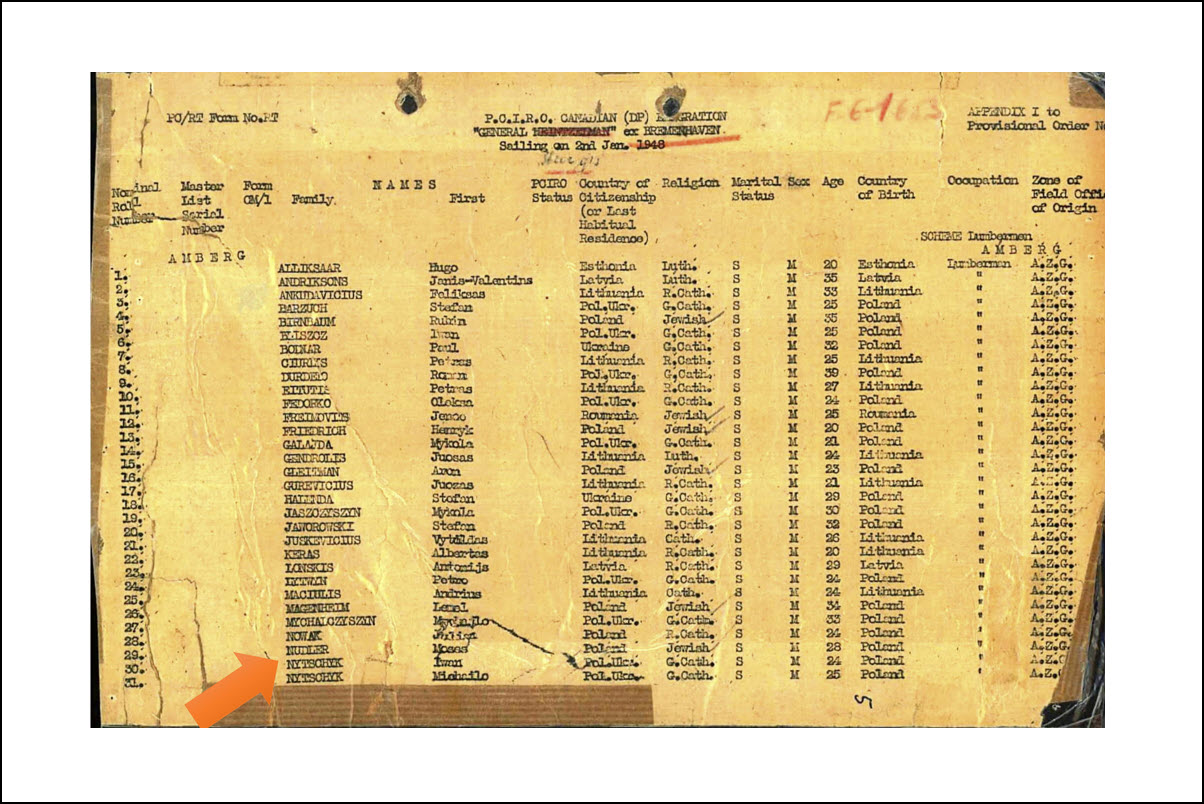

Harold and Misia eventually emigrated to Oakland, CA because Misia had family there. Morris wanted to emigrate to Palestine with his father and Helen, but was persuaded by Mlynov survivor Getzel Steinberg to go to North America where life would be easier, given the conditions in Palestine. According to Getzel’s son, Gerry, Getzel believed that after their own experiences in the Shoah, their own family should hedge its bet by splitting between Palestine and the US, to ensure their survival.Morris chose to go to Canada, since he had distant relatives in Winnipeg. To do so, he had to first do a stint working with the Canadian Pacific Railway in British Columbia. Morris left Bremerhaven, Germany on the General Sturgis ship, and arrived at Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, on January 13, 1948. From there, he traveled to Allenby, British Columbia.

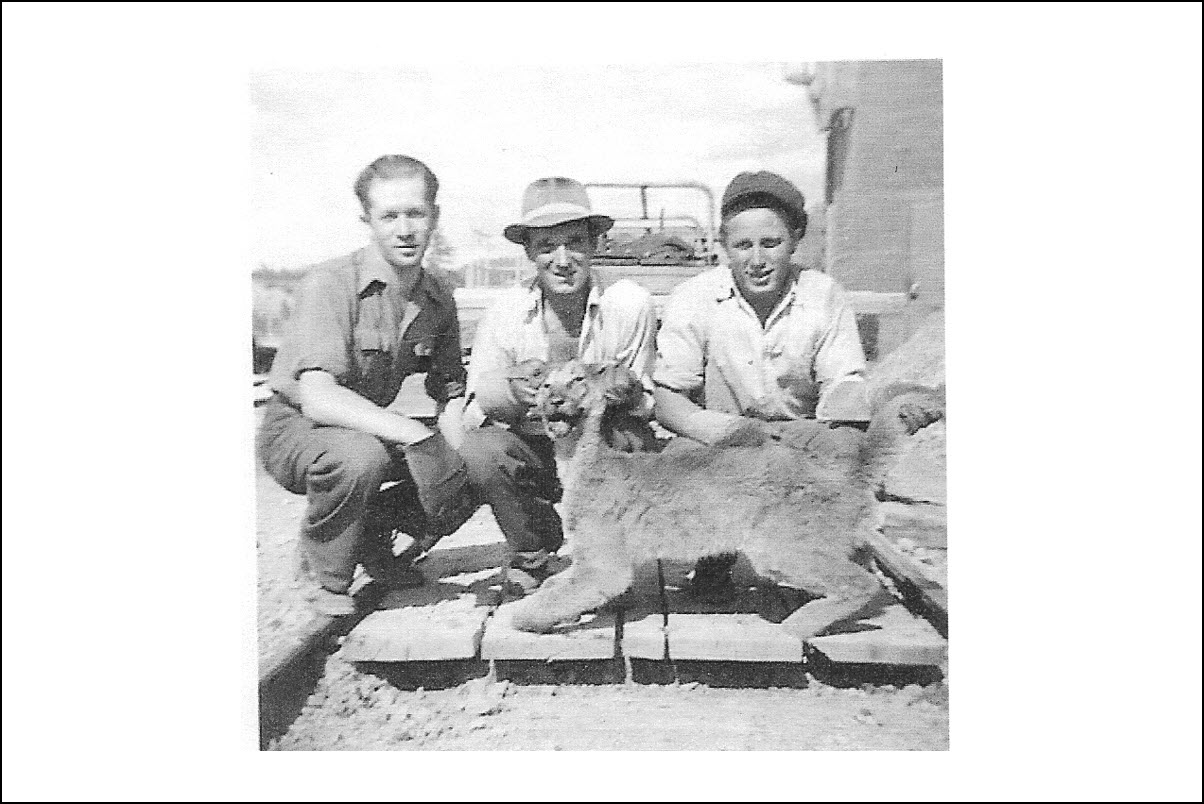

To fulfill his obligation to the Canadian government, Morris laid railway ties along the mountains. One day, a cougar appeared with mouth open and growling. Morris took a crowbar and hit the cougar, breaking its back. The Canadian Government rewarded him by sending $20.

Later in 1948, Morris sent papers to the DP camp in Germany for Helen (Etka) and Aron (Arke) to join him in Canada. Unfortunately, while still in the DP camp, Arke required hernia surgery, developed pneumonia, and died in May 1948 of complications. Helen was devastated by the loss of her father from the routine surgery and was now left alone again without family in the camp. Arke was buried in Straubing, Germany near Passau. In the late 1980s, his remains were exhumed and brought to Oakland, California, where his son Harold (Yehiel) was buried beside him.

Helen finally was able to join brother in Winnipeg and both Morris and Helen stayed on the top floor of a house with distant cousins, the Kormans, on Manitoba Avenue. Morris got a job working as a cutter in a clothing factory. Helen met and married Leonard Fixler in 1949, who was also a survivor. The couple eventually fled the cold weather of Canada and joined Helen’s brother, Harold in Oakland. In 1955, Morris met and married Pauline Shefrin.

Postscript: Morris’s Personal Reflection

Morris believed that God had granted him three miracles in his life. (Even though after the war he lost a lot of his faith, he still led a traditional, Jewish life.) The first miracle he felt was an error his father made in registering his birth year. He believed that if his actual birth year was registered correctly, he would not have been conscripted into the army, and likely killed in the Smordva forest with the other family members. The second miracle was being taken off duty before the great battle of Smolensk. The Russians were defeated with significant losses, and he believed he would not have survived this battle. The third miracle was in 1993 when he had quadruple bypass surgery and suffered a devastating complication. The prognosis was grim. Having his family by his side, whispering continuously that he was strong and had to pull through, gave him the overall strength to recover.Helen (Nudler) and Leonard Fixler had two daughters and a son and many grandchildren. Helen is still alive today in 2021 at the age of 94. Harold Nudler and Misia had two children, Harry and Judy. Harold passed away in 1992. Morris Nudler and Pauline (Shefrin) had two children; Marla and Aaron, and five grandchildren. Morris passed away on July 2, 2004.

Further reading

Listen to Helen speak about her experiences.

Return to the beginning of the Nudler story.

Compiled by Howard I. Schwartz, PhD***

Updated:July 2024

Copyright © 2019 Howard I. Schwartz

Webpage Design by Howard I. Schwartz

Want to search for more information: JewishGen Home Page

Want to look at other Town pages: KehilaLinks Home Page

***

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If it has been useful to you, or if you are moved by the effort to preserve the memory of our lost communities, your JewishGen-erosity would be deeply appreciated.

- History