|

Yaruha,Ukraine

|

|

Life in Yaruha | Emigration | Landsmanshaft

MOISEY GOIHBERG (born 1920) and SIMON GRINSHPOON (born 1916), both Holocaust survivors who grew up in Yaruha, provide colorful, detailed descriptions of Jewish life in the shtetl in interviews conducted by Centropa.org in 2002. Select portions of the interviews are presented below, courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Centropa collection.

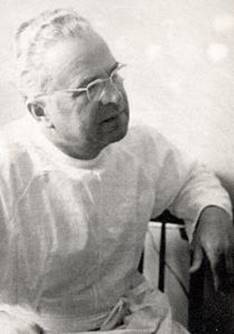

MOISEY GOIHBERG Centropa Interview, 2002

This is a photo of me taken on my 3rd birthday in Yaruga in 1924. It was a tradition in our family that the children were taken to a photo studio to have a photo taken on their birthdays. I was born in Ivanovka on 23rd May 1921 and was named after my grandfather Moisey. I was 6 months old when my parents sold their house and moved to my mother's parents home in Yaruga. There, my father bought a vineyard. We lived near my grandmother Blima and Aunt Rachel. My father bought half of a house. We had two rooms: a dining room, a bedroom, and a kitchen. The toilet was in the yard. There were mainly old wooden houses in Yaruga, but our house was made of stone. The houses were close to one another, very much like those in Marc Chagall's paintings. I can't remember the titles of his pictures, but the village resembled the images created by this artist.

There were 3 synagogues in Yaruga. Each one was attended by members of different professional guilds. This was a tradition. Perhaps, it was for the sake of seeing and talking to one another. Besides, they all contributed money and it was good to know that the money went to their own group. My parents attended the largest synagogue of vine growers only on holidays. There were rabbis, a schochet and a melamed in Yaruga. There was a cheder at the synagogue. I didn't attend it, but I remember other boys going to the cheder wearing kippot and carrying huge volumes of the Talmud.

There were no gardens near the houses. There was a shed near our houses where we kept two horses before the collectivization. I also used to keep rabbits in this shed. My mother bought vegetables and meat from the local Ukrainian farmers. On Sundays there was a market in the central square where farmers from the surrounding villages came to sell their food products. They came on horseback or in bull driven carts or on foot. Those who came on foot put on their shoes before they entered the town, as they were walking barefoot. Girls, women and men wore beautiful, embroidered blouses and shirts. Men wore sheepskin hats at rakish angles. The market lasted a whole day. By the end of the day many men got drunk and there were fights. But they didn't touch Jews. I don't remember one single expression of anti-Semitism in pre-war Yaruga. This bright, colorful market existed until the late 1920s. There was also a cultural center or club in Yaruga. People turned one of the bigger sheds into a club. There was an amateur theater organized in this club in the late 1920s. They staged some plays by Jewish writers; one of them was Sholem Aleichem, whose plays were staged in Yiddish. The local Jews spoke Yiddish. They communicated with the Ukrainian farmers in Ukrainian. Ukrainian farmers also knew some Yiddish.

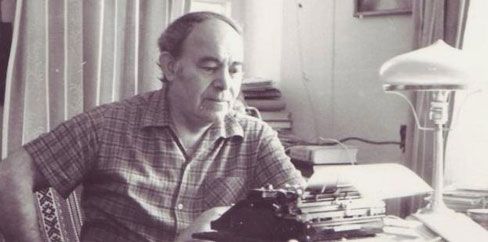

SIMON GRINSHPOON Centropa Interview, 2002

My mother, Leiba Grinshpoon [nee Goldenberg] came from the town of Yaruga. Her father Mordukhai and her mother Anya were born in the 1830s. There were about 300 Jewish families in Yaruga. Ukrainian farmers lived in a small village near Yaruga. The people of Yaruga grew wine. Some of the Jews were craftsmen and merchants. There were tailors, shoemakers, glasscutters, carpenters, plumbers and barbers among them. Wine growers were considered to be of a higher class than the rest of society in Yaruga. It was common opinion that they were the wealthiest and most honest people, while tailors or shoemakers, for example, could take advantage of their customers. Parents didn't allow their children to marry someone from a craftsman's family. My mother, when speaking about such cases, would even comment angrily, 'He [someone] should rather have married a Russian girl.

There were four synagogues in Yaruga. Depending on their profession, the town people went to different synagogues. The biggest one was for richer people. It wasn't just a synagogue - this was a bes medresh, as we called it in Yiddish. There was a small synagogue called shneyders shilekhl a little synagogue for tailors. Workers and laborers had their own synagogue, too, and there was also a prayer house for everybody. There were a rabbi, a chazzan and two shochetim in Yaruga. They all attended the main synagogue, the bes medresh. There was also a Christian church in Yaruga. On Sundays there was a big market in the central square, where farmers from the surrounding villages were selling their products.

My grandfather on my mother's side, Mordukhai Goldenberg, was estate manager for a landlord called Vinogradsky. Vinogradsky had a big estate in Yaruga. He relied on my grandfather's expertise very much. My grandfather's advice on all matters of everyday life was much valued by many people. Ukrainians called him 'Mordukhai, the Smart'. After my grandfather died his son Isaac replaced him at this position.

Uncle Isaac was a very intelligent man. His wife Frieda died some time before World War II, and his children, two sons and five daughters, moved to different towns. Isaac was alone in Yaruga at the beginning of the war. He didn't want to evacuate. He survived the occupation, and so did all other Jews in Yaruga: They were supported and rescued by their Ukrainian fellow villagers. Isaac died in Yaruga in 1975 at the age of 90.

When the Civil War began, there were raids .My mother persuaded my father to move to Yaruga. She wanted to live in a place with a bigger Jewish population. They moved to Yaruga at the beginning of 1918. My mother was right thinking that they would be safer in Yaruga. Jews and Ukrainians always supported each other and got along well. The Jews formed a self- defense unit and defended their town along with Ukrainian supporters from the village attached to Yaruga. My father and his brother Liber were brave men and weren't afraid of anybody.

During the first years after we moved to Yaruga we had a pretty hard time. We didn't have a house of our own. My father didn't have a job. My mother's brothers, Isaac and Moisey, and my father's brothers, Gedali and Liber, were supporting us .In the beginning we lived with Moisey and Isaac and their families, but later we rented an apartment. We paid about 400 rubles per month, which was a lot of money. It was my mother's dream to have a house of her own. My mother had a golden watch on a golden chain and a winter coat with fox fur. These were the two most valuable things my family possessed. In 1924 my father went to Mogilyov-Podolskiy and sold them for 320 rubles. My parents bought an old shabby house with a thatched roof from the miller for this money. Actually, they only bought a plot of land on which they could build a house of their own. However, there was no money left for that. Uncle Gedali brought us three horse-driven carts full of wheat and one with flour. He also gave my father 500 rubles. My mother didn't want to accept it, saying that they wouldn't be able to pay back the debt. Gedali insisted that we accepted what he was giving us. Thus, Gedali helped us to build a big brick house with a huge wine cellar. We didn't know that the time of collective property was approaching and that the vineyard wouldn't be ours. We had four rooms in this house: a living room, a dining room, our parents' bedroom and a children's room. We also had a kitchen with a big Russian stove in it. There were sheds and a stable.

My mother was always kind of a leader in our family. She decided that instead of doing random work my father should start his own business. My parents decided to grow wine. In 1923 my father took a loan from the Agricultural Bank, and in association with another farmer he bought a small plot of land. Wine wasn't grown in Ukraine at that time and they had to order it from France. In the summer of 1924 my father planted the vines. Vines yield grapes after four years. To make a living my father decided to start making wine. He borrowed money from widow Milshtein, who had three daughters and loaned money for her daughters' dowry at 3% per month. My father bought grapes and made very good wine. He learned how to make wine barrels and even sold them. My father didn't sell wine before Christmas when it became more expensive because of the season. He managed to pay back his debts and bought grapes again and again until the time had come to harvest his own grapes. However, there was a terrible rainstorm in the first year that destroyed our harvest. My mother cried, but my father felt very optimistic. He bought grapes again and made wine.

The following year we had plenty of grapes and my father made his own wine. But then collectivization began, and my father had to join the collective farm. He was reluctant to give away everything that he had worked for so hard. He joined the Jewish wine making collective farm. [Jewish collective farms were formed for the Jewish population living in rural areas in the course of collectivization in Ukraine.] There were three collective farms in Yaruga: one Jewish and two Ukrainian. My father never regretted joining this collective farm. He was paid well for his work, and the people were hard-working and wealthy. My father was involved in wine- growing in the beginning, but later he switched to a more familiar activity and became a miller.

When I was 4 years old, I went to cheder along with other boys of my age. We studied the basics of religion, Yiddish, arithmetic and other subjects. We studied at somebody's home, kids and teachers together, taking turns: one month we were at my home and the next month at somebody else's. We had vacations at Pesach and Rosh Hashanah.

In 1924 I went to the Jewish school in Yaruga. There were two schools in our town: a Ukrainian lower secondary school and a Jewish primary school. Since I could read and write, I finished primary school in a year. The Ukrainian school was also turned into a four-year school, and so I went to the Ukrainian lower secondary school in Subbotovka [3 km from Yaruga]. Every day I went to school on Foot.

At the beginning of 1946 I visited Yaruga. I met my Uncle Isaac. He had survived the occupation. Yaruga was the only place where Ukrainians helped to save almost all Jews. There were no occupants in town. I had tears in my eyes and felt great pain in my heart. I left. I visited Yaruga last year when a film about the righteous men of Yaruga was being made.

Note: The Moisey Goihberg and Simon Grinshpoon interviews (click names to see entire interviews) and photos are provided courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Centropa collection.

GALINA ZALUTSKA 2015 VISIT TO YARUHA

Galina Zalutska visited Yaruha in 2015 and wrote of her journey in a blog on the Ukraine Incognita website, portions of which are presented below. The following excerpts and photos are provided courtesy of Ukraine Incognita on behalf of Galina Zalutska.

Everything is forgotten. In complete oblivion are the people who lived here, and from whom only destroyed and half-destroyed houses remained. Not a trace of vineyards and cultivated lands remained. The money collected for the memorial to thousands of innocent victims disappeared without a trace. And only the tombstones in the abandoned cemetery could tell something to a tourist who happens to visit here. But he will also leave bewilderment where did such symbols and inscriptions in the Hebrew language come from in this borderland and deserted village?... a destroyed Jewish house .This house belongs to history. Here they lived, loved, raised children, enjoyed life. And at some point, it all fell apart. But it was not an earthquake, a hurricane, a tornado, a bomb dropped from the sky, or any other cataclysm. And how probably, it is difficult to leave their nest, which has been filled for centuries, forever.

I am showing these houses for those who may be somehow connected with Yaruga. Maybe someone will recognize something familiar here. After all, no one demolishes these houses. So, the descendants of their owners are still alive. Houses stand as if waiting for their owners. They do not destroy them, do not open windows and doors for their own needs. And this once again speaks of the uniqueness of this village and its inhabitants. But time - time inexorably does its job... And once-living houses become ghost houses... And it is sad and uncomfortable to see them.

Not a single Jew has lived in Yaruga since the last decade of the last century. But the memory of them remained. What more! The best buildings in Yaruga repairs the hospital and the House of Culture were built by Jews in the 60s of the last century. Of course, the building of the House of Culture requires appropriate. But agree - it is wonderful.

There was always a library on the second floor, which is still there today. It is run by the lovely Tamila, who greeted me warmly and told me a lot about her native village. I noticed that they still don't have Internet in Yaruga.

Yaruha Culture House, 2015

GRIGORY POLYANKER Yaruga From The Last Meeting with Solomon Mikhoels 1998 Source: Jewage.org, courtesy of JewAge

Yaruga is a small village in Podolia, a Jewish settlement that is already several centuries old. I don't know if any of you have ever been to Yaruga, which is hidden away from the main roads between the coast and deep valleys, yarugas, because of which the name Yaruga stuck to it.

On one side of the forest (ravine) at the very bank of the Dniester, between mossy rocks and dense bushes, a small town was adjoined. Here, between the rocks, its streets and alleys stretched. Simple workers lived here. Hundreds of years ago, their ancestors, persecuted and driven from the cities of Europe by the Spanish inquisitors, came to a wild and deserted shore. There were several dozen Jewish families. On the high slope of the mountain, which stretches to the very edge, they planted vineyards. They made famous Spanish wines.

On the other side of the forest, a Ukrainian village stretched to the bare steppe, and for many years, a Jewish shtetl and a Ukrainian village lived side by side. Not far from the vineyards, there is an ancient cemetery surrounded by a wall, where you can still read on the gravestones that they are 400 years old and more, and fortunately, they have survived to this day, although they have settled in the ground. The life of these Jews, who planted wonderful vineyards here, is shrouded in living legends. The locals called them "Spaniards". Many years ago, Jews from Podolia, Kamenets-Podolsky, Starokonstantinov - craftsmen who forged harnesses and sewed clothes - also settled next to the "Spaniards".

People loved the land, their vineyards. They lived in peace and great friendship with their neighbors on the other side of the forest, the Ukrainian villagers. They shared grief and joy. They experienced good and bad together. When trouble happened, a heavy hail fell on the vineyards and knocked out the fruit, and the shadow of famine hung over the shtetl. The Ukrainian neighbors came to the rescue, sharing their last piece of bread. Drought burned the neighbors' fields, and winegrowers from Yaruga came to the rescue. That's how they lived. They celebrated big holidays together and had fun, visiting each other. When trouble happened here or there, they grieved together. The village and the shtetl almost grew together. The church stood on the land of the shtetl, and part of the synagogue stood on the land of the Ukrainian village: one day a fire broke out in the church, and firefighters from the shtetl came running and put out the fire. The Jews saved icons, banners, all church property from the flames, and the entire village was grateful to their neighbors. During the flood, the synagogue, one wall of which faced the Ukrainian village, was badly damaged. The wall collapsed. Then Ukrainian peasants came and repaired the synagogue in a few days.

When a collective farm was organized in Yaruga and a collective farm appeared in the Ukrainian village, the neighbors became even closer friends. They organized a common club in the middle between the shtetl and the village, and people came here to listen to concerts and watch movies. On wonderful summer evenings, you could hear Jewish songs sung by boys and girls from the Ukrainian village. And in Yaruga, Jewish boys and girls sang Ukrainian songs no worse. Ukrainian youth understood Yiddish, and in the Jewish shtetl, Ukrainian speech was heard. Until the fourth grade, students studied separately in their native language, and then went to the same school.

Emigration Stories

In the early 1900 s an estimated 200+ Yaruha residents and those who were born in Yaruha, emigrated to the United States, Canada, Brazil and other countries. Click here for a list of many of these individuals, compiled from FamilySearch.org immigration, naturalization and draft records.

Below are a few Yaruha family emigration stories. If you would like to contribute your family s story, please contact me.

ROSOVSKY FAMILY

This writer s great-grandparents, Borech and Rivke (born Susner) Rosovsky, originally were from the neighboring shtetl of Dzhurin. All six of their children were born in Yaruha in the late 1880s and early 1890s. The family members emigrated to New York City separately over a span of five years. The first to make the journey was 18-year-old Meir, the eldest, who arrived at Ellis Island in 1907, followed in 1910 by brothers Srul age 19 and Chaim age 15. My grandmother Gitel, age 20, and sister Rise, age 18, arrived together in 1911. The last to arrive were my great-grandparents with their youngest child Yosef, age 10. Finally, in 1912, the family was together again.

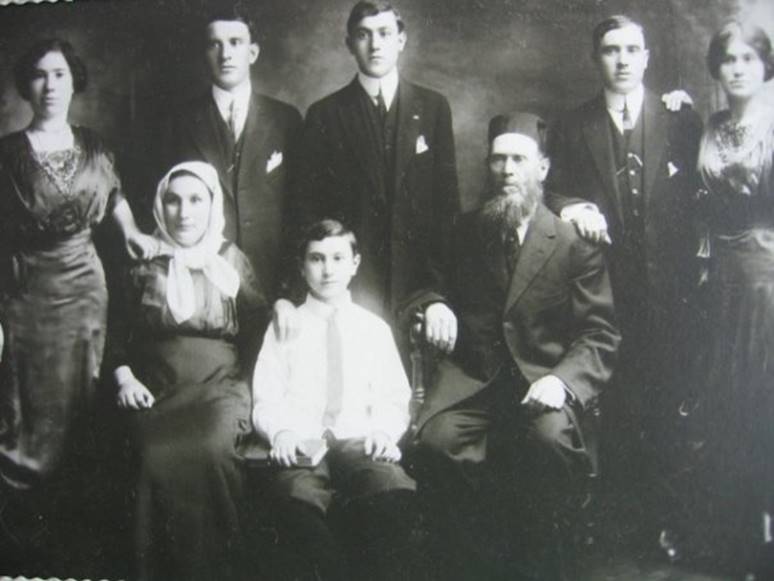

Rosovsky / Rosen family circa 1913 Gussie, Meyer, Hyman, Isidor, Rose, Rebecca, Joseph, Boris

As did so many other immigrants, my Rosovsky ancestors settled in a tenement on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Their address in 1912 was 200 Orchard Street, steps away from what would become the Tenement Museum at 103 Orchard Street. By 1915, the Rosovskys had changed their surname to Rosen, and had Americanized their given names to Boris, Rebecca, Meyer, Isidor, Hyman, Gussie, Rose, and Joseph. The family remained in the Lower East Side moving to East 3rd Street after their three eldest children got married. In 1914, my grandmother Gussie Rosen married Solomon Freedman who grew up in Ataki, Bessarabia a shtetl just on the other side of the bridge that spans the Dniester River.

I found this much-worn

1917 Russian Ruble in my Aunt Rae Friedman Kaplan s closet some years ago.

My cousin, Rena Miller Dev za, recalls a story about the pogroms told to her by her late grandfather and my great uncle Hyman Rosen, and shares some personal memories growing up with him in Brooklyn:

He always told it with a maniacal laugh that I knew instinctively was not a laugh. It was terrifying to me as a young child 4-5 years or so. I remember the quality of this laugh more than anything else. It was clear to me that this was like screaming or crying as it described horrible stuff and as a child it unnerved me. If you remember my grandfather he was often laughing, was often merry. He often teased me - like when we went down to the cellar, he would tell me to mind the mice. He would open and close the mouth of a smoked white fish and tell me it was alive.

It was a simple story. He told me the Cossacks would come periodically to murder Jews and how he had to hide under the bed. And this happened often. Clearly, he survived all the attacks. And that is why his family left Russia. It was either be killed or leave.

He was a great cook and often cooked for me: potato latkes, matzoh meal latkes, jello with whipped cream all stand out in my mind. Oh, and seltzer with cherry syrup along with eggcreams. The cherry syrup was also made by Foxe s Ubet. The seltzer and syrups got delivered by the seltzer man truck which I do remember. He made the best potato latkes I ever had - better than my grandmother s and she was one great cook.

I spent a lot of time with my grandparents in their tailor dry cleaning store in Brooklyn. My grandfather would sit me on the counter and introduce me to the customers as his granddaughter and helper. I also sat by my grandmother who was at her sewing machine, listening to WEVD in Yiddish on the radio. She also translated articles for me from Der Forverts. And she told me about coming to NYC all by herself at age 16 and how she only knew Russian and had to learn Yiddish as well as English.

POSTERNAK FAMILY

Judite Orensztajn of Guivataim, Israel, contributed the following story of her Yaruha family s emigration to Brazil, Israel, and the United States:

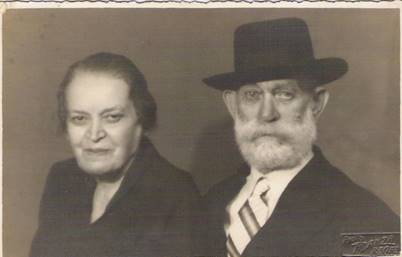

My father Moyses and all his family (parents, brothers and sister) were born in Yaruha. I m afraid they were too poor to have photos. I know the names of my grandparents: Abraham Posternak/Pasternak and Chaia Margulis (photo on left). I have a photo of them with the names of their parents (written in Hebrew). The photo was taken in Recife, Brazil, when they were old.

Chaia Margulis and Abraham Posternak, Recife, Brazil; Posternak Family, circa 1960, Brazil

They emigrated to Brazil and they are buried there, in Recife. I suppose that my grandfather emigrated in 1912-13 (leaving my grandmother pregnant with my father) and not until about 1920, after the end of the First World War, did he succeed in sending money for the rest of the family to come and join him. I have no information if my grandparents knew people that had emigrated to Brazil, but the fact is that in Recife, where they lived, there was a tiny Jewish community, and part of them had come from the same region. My father had two brothers, Jacob and Isaac, and one sister, Busi. Their families live in Brazil (Recife and Rio de Janeiro). Here in Israel there are two other cousins. I have a sister that lives in Rio de Janeiro, but her 3 children live in the USA. About the Margulis family, two sisters of my grandmother (Brana and Batsheva) emigrated to the USA, and one day I found out that I have many relatives there about whom I had never known. I was found by the researcher that was hired by the American family thanks to the site of JewishGen

|

|

Landsmanschaft

PROGRESSIVE SOCIETY OF YARUGA

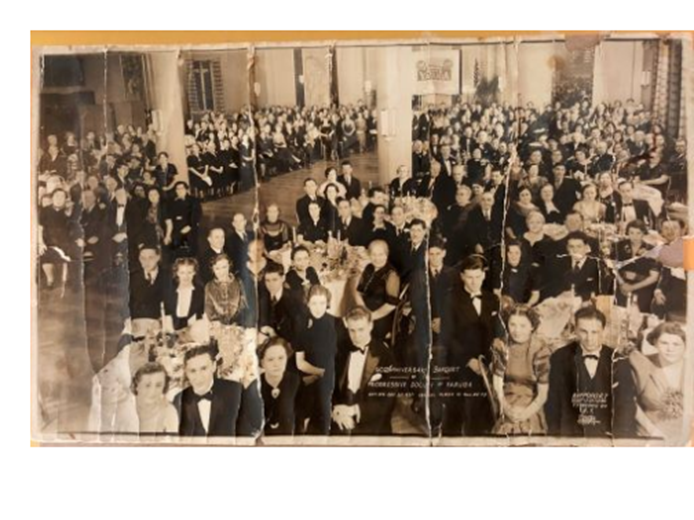

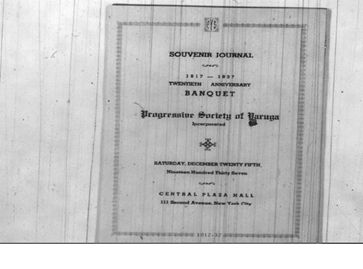

Founded in 1917, the Progressive Society of Yaruga helped Jewish immigrants from Yaruha by providing financial, medical, burial and social support. Some years ago, this writer found a very fragile large photo rolled up in a closet of the Bronx home of my aunt, Rae Friedman Kaplan. If you, the reader of this page, had ancestors from Yaruha who lived in or near New York City in the 1930 s, chances are those ancestors are somewhere in this photograph of the Society s 20th Anniversary Banquet held at Central Plaza in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. My grandparents, Gussie (Rosen) and Solomon Friedman are sitting at a table with my great aunt and uncle, Fanny and Hyman Rosen. Photos of the 20th Anniversary Banquet of the Progressive Society of Yaruga, New York 1937

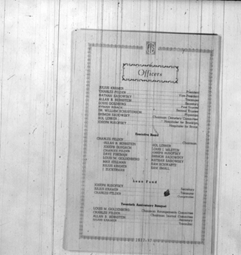

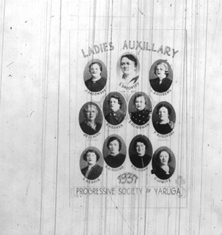

Below are images of several pages of the Society s Anniversary Journal which contains names of members, history and activities of the Society, many advertisements from merchants and benefactors. The complete Journal may be seen here, and was sourced, downloaded and compiled by this writer from microfilm held at the Dorot Division of the New York Public Library, Schwartzman Building.

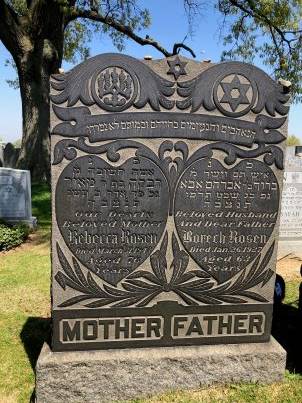

The Society purchased burial plots at two cemeteries in New York: Mount Lebanon in Queens, and Beth David in Elmont. Recently this writer visited Mount Lebanon Cemetery where my great grandparents and great aunt and uncle are buried in the Society s section. A list of all Progressive Society of Yaruga section interments at Mount Lebanon taken from the Cemetery s website, may be accessed here.

Mount Lebanon Cemetery, Glendale Queens New York Gravestones of my great grandparents, Rebecca (Rifka) and Borech Rosen (formerly Rusavsky)

|

|

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If you feel there is a benefit to you in accessing

this site, please consider supporting our Created and Compiled by Rita Geister Liegner Copyright 2024 Rita Geister Liegner

|