|

Yaruha, Ukraine

|

||||

|

History of Yaruha

Geography | Jewish History | Pogroms | Holocaust | Post WWII

GEOGRAPHY

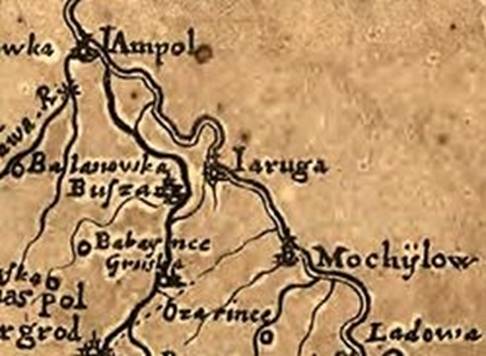

Named яр or ravine in English, Yaruha is situated among the steep hills and cliffs along the Dniester River. Yaruha is cited in documents dating back to the early 17th century and appears in the 1648 map below, the year of the Cossack uprising against Polish leaders led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky (c. 1595 1657) in the Polish-Lithuanian territory that is now Ukraine.

After the annexation of Ukraine to the Russian Empire in 1793, and prior to 1923, Yaruha was part of the district of Yampol in the Podolia region. In 1923, with the establishment of the Soviet Union, Yaruha became part of the district or oblast of Vinnytsia, Ukraine SSR. During World War II Yaruha was annexed to the Moldovan territory of Transnistria under Romanian-German rule. After the World War II, Yaruha returned to the control of the Soviet Union as part of a region of land called Bukovina, which at that time was divided between Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine . The Soviet army immediately captured the place from the defeated Romanians. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1990, both Moldova and Ukraine became independent countries. Today, Yaruha is a small town located in the Vinnytsia region of Ukraine.

The precise date of arrival of the first Jews to Yaruha is not known but is thought to be sometime during the mid-18th century. Jews in Yaruha joined with Jews in nearby settlements to form a larger Jewish community of about 165 people under one eldership recognized officially by the governing authorities of the Podolsk province. In 1784, there were 14 Jewish households in Yaruha, with about 60 Jewish inhabitants. Three years later, in 1787, there were 16 Jewish households. By 1853, the 171 members of the Jewish community of Yaruha, led by Rabbi Avrum David Floim, were worshipping in a stone synagogue. A wooden religious school had been constructed with classes conducted in Yiddish.

In the years 1844 and 1848 there were at least 44 recorded Jewish births in Yaruha and at least 10 recorded Jewish marriages. The addition of another synagogue in the early 1860 s prompted the provincial authorities in 1863 to institute a law regulating the number of synagogues and Jewish prayer schools. The new law allowed just one prayer school for every 30 homes, and one synagogue for every 80 homes. As a result, one synagogue in the town was closed. By 1889, there again were two synagogues serving 559 Jews, and a third had been added by 1900 or shortly thereafter. Rabbi Israel Maidanik led the Jewish community starting in 1882, succeeding his father, Rabbi Aaron.

During the mid-19th century, Jews in Yaruha were engaged in agriculture, farming food crops and cotton, vine growing, wine making and wine trading, fishing, bread-making, and in small trade and traditional crafts, primarily knitting. There were a few artisans in the town. An 1871 report from the governing authority, lists 520 mostly Jewish Yaruha residents assigned to the trading class. Another 590 residents were assigned to the rural class. At the time, a total of 157 houses existed, a few of which were made of stone, but most of wood. Jewish houses and shops lined both sides of the main street running through town. Plots of land of about 5 acres each were purchased in 1872 by 33 Jewish families with arrangements to make payments over the next 40 years. Jews planted crops and grapevines and made and sold wine earning on average from 300-600 rubles per year. The wine was of good quality. Jews not engaged in winemaking took advantage of the town s location on the Dniester River to trade merchandise along the trade route from Odessa to other commercial centers.

The winter of 1890-91 brought severe frosts to Yaruha, damaging vineyards, and causing widespread poverty among the Jewish community. Production of wine decreased by 90%. Even winegrowers had no wine for their own tables. Several years of repeated crop failures placed winegrowers deeply in debt, unable to manage redemption payments to the provincial authorities. In 1896, a petition by the vineyard owners to defer payments for five years was denied and Jewish winegrowers faced the prospect of being forced to sell their household property and vineyards. Even the formerly wealthy worked as day laborers in neighboring shtetls, walking back and forth, forced by the rules of the provincial authorities to return to Yaruha each evening. The local Jewish population had grown and was made denser by the arrival in 1893 of Jews expelled from a village in Bessarabia just across the Dniester River. Adding to the poverty and population density that endangered the Jewish community was the threat posed by the 1896 typhus epidemic spreading throughout Podolia. A. S. Vaynshteyn, a local physician, treated sick patients free of charge.

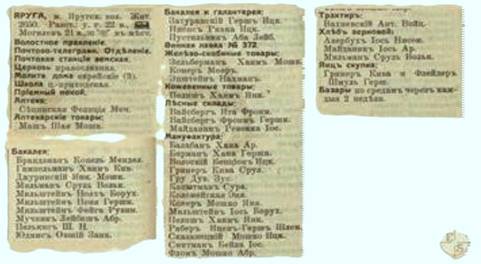

The situation of Jewish winegrowers improved by the turn of the century thanks to the financial assistance of Jewish philanthropist Baroness Clara de Hirsch (1833-1899) and the implementation of the recommendations of agronomists of the Jewish Colonization Society (JCA) created in 1891 by Baron Maurice de Hirsch (1831-1896) to provide support for Jewish emigration and farming communities. A 1913 business directory of Yaruha, shown below, listed a pharmacy, grocery store, haberdashery, wine shop, hardware, engraver, bakery, leather goods, lumber yards. Most business owners were Jewish. Names on the list included Dzhurinsky, Milshtein, Malketivich, Vadeberg, Berman, Raber, Averbukh, Shmuel Gerov. A bazaar in the center street was held twice a month.

1913 Yaruha Business Directory

Source: Courtesy of the Jewish Ethnographic Museum, myshtetl.org from The Entire Southwestern Territory: A Reference and Address Book for Kiev, Volyn, and Podolsk, M.V. Dovnar-Zapolsky, 1913.

This Russian word (Pogrom) is included in all European languages of the world. Jews were smashed everywhere and always, but only on the territory of the Russian Empire, pogroms reached unthinkable proportions. Moreover, each new wave of pogroms was worse than the previous one. The surviving pogroms of 1905 did not think it could be worse, but then 1917 came to their life. And 1918-1919 overshadowed everything that was previously. There was no place that would not have suffered from the pogrom, and many more than once. Part of the Jewish colonies was wiped out long before the Holocaust arrived in these parts. From JewishPogroms.info, a website dedicated to victims of the pogroms including the 89 Yaruha residents who survived, and the 16 who perished.

The violent pogroms that took place throughout Podolia in the years 1881, 1905, and in the pre-WWI years, are described by David Bickman in Podolia and her Jews, a Brief History published by JewishGen.org, Ukraine Research Division. Excerpts from the article follow:

In the early 1880's a number of pogroms against Jews occurred throughout the Ukraine, 63 of which were in Podolia, the province in which Yaruha was located. Of the pogroms that occurred throughout the Pale in 1905, 37 were in Podolia. Before 1919, the pogroms primarily occurred in the cities . After 1919, they were more prevalent in the villages .The defeat of the Ukrainian nationalists by the Bolsheviks was followed by numerous terrible pogroms against the Jews in the Ukraine Of the three periods in which pogroms occurred in Ukraine, the worst period was from 1917-1921 . In Podolia alone, 213 pogroms are recorded, the majority having been committed by supporters of one or another of the various Ukrainian nationalist movements that were operating at the time in the region.

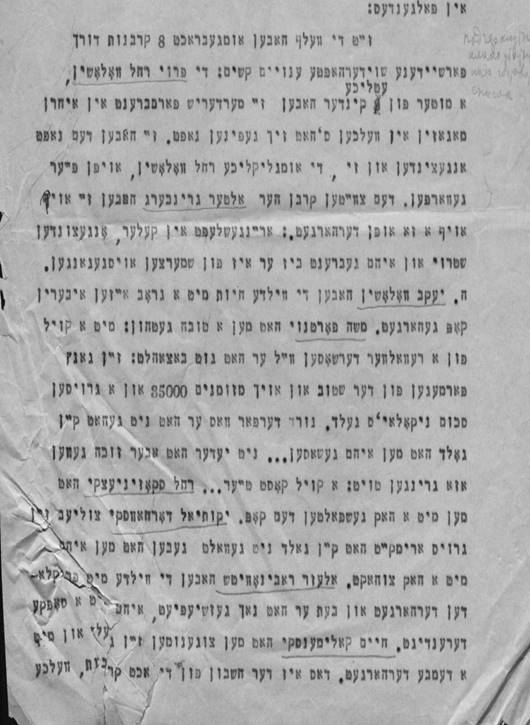

The YIVO Center for Jewish History Archives collection contains several contemporaneous pieces of correspondence and reports in Yiddish and Russian documenting the 1919 pogroms in Yaruha perpetrated by soldiers of the Ukraine Volunteer Army. Below is one such letter written in 1919. The English translation may be viewed here. Additional letters and documents from the years 1919-21 in Yiddish and Russian from the YIVO Center may be viewed here and here and here.

A video oral history on Youtube in which Henry Kellerman, author and psychoanalyst, talks about his father Samuel s experience in Yaruha during the pogrom of 1919 may be viewed by clicking on this link: Pogroms And Jewish Resistance In The "Two-Blink Shtetl" of Yaruga | Yiddish Book Center.

One week after the Nazis entered the Yaruga in July 1941, all Jews were quickly resettled to the outlying street of Maarl ch, several families to each house. A Jewish ghetto was created surrounded by fencing. Jews were forbidden to go beyond the fence and were required to wear a yellow circle about ten centimeters in size on their chest and back. Noach Muchnik, chairman of the collective farm, was appointed head of the ghetto. Jews still worked on the collective farm, cultivated the vineyards, and also repaired harnesses, hemmed felt boots, and processed leather. The police confiscated all valuables from the Jews, and then all products made of non-ferrous metals. Life in Ghetto Yaruga is described in memoirs published in Israel by Amutat "Zikaron" in the 2016 book Bells of Memory.

On July 28, 1941, hundreds of Jews who had been deported from Bessarabia and the northern section of Bukovina were heading to the Yampol region and nearing Yaruha when they were stopped by the Nazi SS team, were shot and killed, and thrown into the ravines, then covered with earth. It is estimated that about 1,000 Jews were killed that day. The Jews living in Ghetto Yaruha as well as some of the recently arrived Jews from Bessarabia were protected by many of their non-Jewish neighbors, documented in an article by author Boris Khandros entitled Yaruga: Righteous Village published in ZN, UA Mirror of the Week, September 10, 1999

In 1968, members of the Yaruha collective farm organized to exhume the bodies buried in the 1941 mass murder and provide proper burials for their remains. Below are photos of the 1968 exhumation.

In October and November 1941, after the formation of the Romanian zone of occupation of Transnistria, about 500 deported Bukovinian Jews were settled in Yaruha, almost doubling the shtetl s Jewish population. A ghetto council was created, headed by Shoikhet Wieder from Romania. The Ukrainian police in Yaruha was led by German-appointed Fedor Kryzhevsky, who headed the secret Salvation Committee and who before the war, was the chairman of the collective farm. Kryzhevsky, with several other Committee members secretly supported the Jewish partisans; he organized and took care of housing the deportees who arrived in Yaruha in the homes of the local Jews. He arranged for local non-Jews to hide 400 Jewish families during the months of German occupation prior to Romania taking over. He also circumvented the ghetto order and expanded the ghetto to almost the entire former Jewish neighborhood, so that most of the Jews could return to their previous homes. Thanks to him, the ghetto had relatively good living conditions; for example, Jews could leave the ghetto without much difficulty. Yad Vesham has recognized Kryzhevsky as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. A 2003 documentary film Old Mill by Igor Negrescu based on the book The Place that Doesn t Exist by Boris Khandros, highlighted those in Yaruha and other nearby towns who saved the Jews from the Nazis. The film s release prompted the Jewish Fund of Ukraine to request to the President of Ukraine in 2011 that the town of Yaruha itself be granted the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

Martin Gilbert in The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust (2004): writes:

In the remote village of Yaruga, Fedor Kryzhevsky, whom the Germans had appointed the village elder, but who secretly organized local resistance, ensured, in an impressive act of compassion, that all four hundred Jewish families, as well as Jews from Bukovina and Bessarabia who had found refuge in the village, were found hiding places by their Ukrainian neighbors. Kryzhevsky also persuaded the local German administration to allow a number of Jews to live openly, as specialist wine makers, in a region where wine making was an important part of the economy. To feed the large numbers of Jews in hiding, Kryzhevsky organized a secret food store. For eighteen months, the hidden Jews remained undiscovered: when the Romanian authorities took over the administration of the region from the Germans in late 1942, they ignored the Jews, whose survival was thereby assured.

One of the problems that the ghetto council faced was the night attacks of peasants from the Bessarabian village of Yarova who crossed the Dniester and robbed Jews. After unsuccessful attempts to organize self-defense, the Council reached an agreement with the peasants. As an alternative to being robbed, Jews of Yaruha would instead participate in the smuggling of goods from Bessarabia to Transnistria. The resale of contraband goods significantly improved the financial condition of the ghetto inhabitants.

In January 1943, 369 local and 416 Romanian Jews lived in Yaruha. Many young people had been sent to forced labor in camps in Transnistria. In September of the same year, according to gendarme statistics, among those deported were 6 Bessarabian and 472 Bukovinian Jews. Of the local Jews in Yaruha, 56 people died during the occupation; of all Jews living in Yaruha including those originally from other nearby communities, a total of 100 people died in the years 1941-1944.

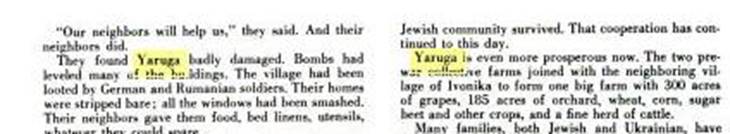

Yaruha was liberated on or about March 20, 1944. In the post-war period, several dozen surviving Jewish ghetto prisoners lived in the village joined by former front-line soldiers. A description of post-war Yaruha from a 1956 article reprinted in a 1966 issue of Soviet Life is excerpted below.

The post-war collective farm in Yaruha is described by Ion Degen in his 1986 memoir "From the House of Slavery" Moria Publishing House, Israel and reprinted by JewAge.org.

A list of Yaruha residents killed in the period 1941-44 may be found by following this link: https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/Vinnista/vin079.html#Page81 . A photo of the memorial to those killed in the occupation in Yaruha s new Jewish cemetery is shown below. The inscription on the monument reads: "Dedicated to men, women, elders and children who were brutally murdered only because they were Jewish. This should never happen again. May we always remember the ones who perished."

Source: Photo courtesy of myshtetl.org; translation courtesy of Marina Nevyarovskiy

References: Myshtetl.org Jewish Ethnographic Museum Boris Khandros memoir in Jewage.org The Bells of Memory: Memoirs of former ghetto and concentration camp prisoners, currently living in Ashdod, Israel, Amutat "Zikaron." Israel, 2016. Wikipedia, Yaruga (Mohyliv-Podilskyi district) Soviet Life, Embassy of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics in the USA, December 1966, issue 112, page 21. ZN/UA Mirror of the Week, September 10, 1999. Martin Gilbert, The Righteous: the Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust, Henry Holt & Co., 2004. Miriam Webster Archival Collection

|

||||

|

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If you feel there is a benefit

to you in accessing this site, please consider supporting our Created and Compiled by Rita Geister Liegner Copyright 2024 Rita Geister Liegner

|