Kolomyya Administrative District, Ukraine

Alternate names: Kolomyja, Kolomea. Location: 48°32' N, 25°02' E

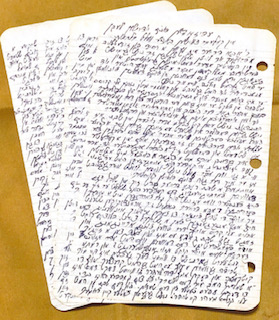

My Life in Kolomea Between the Two World Wars (1914 - 1945) by Aron Stahl (1908 - 2005)

Childhood at the Onset of WWI

I was not yet six years old when the first world war broke

out but, I noticed a big change in daily life. One of the first

signs I remembered was that the only bread available was dark and

tasted much different. I was also aware that bread was hard to

come by. My town, Kolomea, was quickly occupied by the Russian

army. That winter was particularly cold. My entire family

of eight lived in one room because we had no heat. The house was

on a main thoroughfare and was soon confiscated by the Russian army to

serve as quarters for their military officers. The family was

forced to leave. We sought shelter with my brother Gershon who

lived in a small bachelor's apartment near the center of the

city.

I was not yet six years old when the first world war broke

out but, I noticed a big change in daily life. One of the first

signs I remembered was that the only bread available was dark and

tasted much different. I was also aware that bread was hard to

come by. My town, Kolomea, was quickly occupied by the Russian

army. That winter was particularly cold. My entire family

of eight lived in one room because we had no heat. The house was

on a main thoroughfare and was soon confiscated by the Russian army to

serve as quarters for their military officers. The family was

forced to leave. We sought shelter with my brother Gershon who

lived in a small bachelor's apartment near the center of the

city.

Life became very difficult, especially for the Jews. Atrocities against Jews became routine. Jews were robbed, beaten, and taken hostage for ransom by the order of the Russian Commandant, Sechin. During the winter of the occupation, Jews of Kolomea made contact with Jewish Russian soldiers. One of those soldiers was an officer named Shalom Anski. Anski later was the author of the famous Jewish play "Der Dybuk" as well as other eyewitness accounts of the destruction of Galicia. Anski was memorable to me because he prayed daily in the synagogue to say Kaddish for his two sisters who died that same winter.

At the time that war was declared, my father had been away on a business trip in neighboring Hungary and had no way to return. In March 1914, the Austrian army commenced its offensive. There were numerous casualties each day, both among soldiers and the civilians. The Austrians took back the city after a short while, but nothing returned to normal. However, at that time my father was able to return from Hungary, where he had been stuck.

In 1915, my brother Gershon was mobilized to serve in the Austrian army. He never returned. The family feared that my father would also be called up because he was a reserve officer in the Kaiser's guard. The front and fighting armies began to come closer again. The Russians did retake the city, but by then, our family had fled. My four older sisters left by train. My parents, my two other sisters and I traveled by horses and wagon that my father had purchased to allow us to leave. We loaded as much as we could in the wagon and left the city by country roads. We went from village to village in the Carpathian Mountains to the nearby Hungarian/Czechoslovakian border. After a couple of days of travel, we came to Sighet. Although we took the country roads in order to avoid the front, we could hear the shootings as the front drew nearer to Sighet. There was no way to proceed further, so my father sold the horses and wagon. From there, we boarded a refugee train to Moravia. Amid other refugees like us, we arrived at a German village in the district of Schoenberg in Moravia called Langendorf, near Motus (sp) Neustadt. We lived in that village under the dominion of the Austrian government until the end of the war in 1918.

Life as a Child Refugee

I attended school in Langendorf and completed the first and second grades. During our time in Langendorf, we learned that my four older sisters were living in Eiyer (sp) Sudettenland, also as refugees. We also received an official note from the Austrian military headquarters that my brother Gershon had been wounded in upper Italy and had died on November 19, 1917. Later, the family received a few medals for Gershon.

In 1918, we returned home, but it was no longer under Austrian rule. Kolomea was in ruins, with rubble all around. Many people we had known had been killed. The Ukrainians had taken over with a provisional government in the city of Lvov. The Jews were promised autonomy and allowed to have Jewish schools using the Yiddish language. I was enrolled in such a school in the second grade, though I belonged in the third grade. Nevertheless, this situation only lasted for about three months. We were under Romanian rule until 1919, when Kolomea was ceded to Poland under Haller's army. As soon as the city was handed over, pogroms against Jews broke out. Haller's army first murdered a Jewish family of six. A week later, they murdered four Chaloutzim on a Zionist "Hachsharah" in Slobentka near Kolomea. The Chaloutzim were working on a Baron Hirsh agricultural farm in preparation for Aliyah to Palestine. The image of the funerals in Kolomea for those victims permeated my memory for my entire life.

For a short while, the Romanians posted soldiers to act as security guards. Soon after, the Polish army of Pulaski took over for the Romanians. There were promises of security and civil rights for the Jews, but city life had been irrevocably disrupted. The traditional Jewish life never again looked the same. Under the peace agreement after the war ended, the maps of Europe changed entirely. Kolomea was on a triangle of multiple Polish borders. The city became like a restricted zone every 40 to 50 kilometres. Kolomea was surrounded by a borderline of many different countries including Russia, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania. The territory that once was Kolomea was reduced to a little village. The former vibrant economic opportunities to make a living vanished. For the first couple of years after the war, most of the Jewish population in the city received relief from the USA through the Joint Distribution Committee.

Struggle to Contemplate a Future

Most of the young people seeking employment faced great hardship. Government jobs were not available to Jews. Other industries like tobacco, sugar, salt, oil, etc. were monopolies controlled by the government. Jews were not allowed to even engage in trade in those industries. Young people were looking to emigrate, but amid the closed borders and quotas, it was nearly impossible. A lot of young people smuggled into Romania and Czechoslovakia, but were stuck as before in poverty. They found no hope for employment or any future. Young people tried to develop a new industry around Kilims [rugs] and Fillet draperies. These were hand woven in the home with no special tools needed. Others took the products all over Poland to sell them to the Poles who had government pensions and paid in installments. This form of self employment became the livelihood for most Jews in Kolomea.

My father had a younger brother, Leib Stahl, living in the USA. Leib sent immigration papers for my three older sisters, Yetta, Blanche, and Esther. In 1920, they were able to go to the USA. In the meantime, life had to go on. Zionism and Socialism gained popularity with the younger generation. There was hope for an apparent coming return to Palestine. But, very few did go to Palestine because of the limited number of certificates from the British Mandate officials in Palestine.

Despite poverty and being deprived of higher education, I still wondered at how there was no illiteracy at all. I thought it must be the inheritance of the traditions of the previous generations which made Kolomea so famous. There were many notables in all fields of civilization. Kolomea was the birthplace of Hasidism. The legend about the (Besht) Baal Shem Tov took place in the vicinity around Kolomea which was geographically located on that same triangle. That triangle was called the Pokucie and lied at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. In fact, Reb Jehuda Kitover (sp), the brother-in-law of the Besht, was buried in Kolomea. I remembered his gravestone in the old (and first) cemetery in Kolomea. The cemetery was located in the center of the city, just behind the Magistrat [City Hall] building.

The first Zionist Congress held in Basel, Switzerland in 1897 had two delegates from Kolomea. Those delegates were Dr. Salomon Rosenheck, a physician, and Dr. Salomon Singer, an attorney. Throughout my life, I remembered both of them. Other renowned Kolomeans included: Dr. Philip Rottenstreich, Senator and the most prominent economist in the Polish Senate Budget Commission, who later became a member of the Zionist Action Committee. Aleksander Granach was a famous film actor known for his role in "The Yellow Patch" [note: possibly "The Yellow Ticket" or a lost film]. Rabbi Chaim Zvi Thurmin was the leader of the Mizrachi and delegate to the 14th Zionist Congress in Vienna. Naftal Gross was a Jewish writer, and his brother Chaim Gross was a sculptor. Dr. Solomon Bickel was a Jewish writer and journalist. The founder of the Beit Jacob schools for religious training for girls was Sarah Schenirer. I remembered her and also her father, Salomon (Zalel) Schenirer and knew the house where they lived on Legronerz (sp) Str.

The famous author Simon (Shimson) Heller was also from Kolomea. His sons, Abraham Samuel Heller and Lipe Heller, owned a well-known Tallit factory in which the first organized workers strike in the region took place in 1905. In fact, there was a second big Tallit factory owned by Yoyne Zager. Tallitim were shipped all over the world and therefore Kolomea was known in every Jewish community the world over.

My Youth in Kolomea

A curiosity in town were the letters "YHVH," the Hebrew name for God, that appeared in gold letters on the top of the Catholic church. Nobody in the city knew by whom or when it was done. The legend was that a convert to Catholicism had done it. Also curious was that the style of Jewish life was probably not changed or touched for long centuries.

I was in the third grade already in the Polish school after attending the German and Ukrainian schools. I also attended Cheder for Jewish and religious training. My Polish teacher, Tjencilkto (sp), told the students about the name of Kolomea. According to the teacher, the city on the Prut river was then nine hundred years old. So, the city fathers wanted to have a name for the city. They made up their minds to go early one morning to the river Prut. Whoever they would see first, on their first question, whatever the answer, that would be the name of the city. They saw a peasant washing the wheel of his wagon. They asked him, in Ukrainian, "what are you doing?" He answered in Ukrainian "kolomyja" that means, "I'm washing the wheel." For over 900 years, the name was the same.

My father was a Ziditshov Chusid and prayed in the Ziditshov schul. My father was a merchant dealing in a lot of different goods, mostly wholesale. More than twenty people were dependent on him for their livelihood. But, after the war, all this changed. Nothing was the same anymore. I wanted very much to continue in school, but my father wanted me to help him in his business. The business was in partnership with my father's nephew, Solomon Stahl, a son of his older brother Abba Stahl who died in Berlin before the war ended. Abba and his wife Rivka were on their way to retire in Palestine. Because of the war, they stopped over in Berlin where their daughter lived, and there Abba died. His wife came back to Kolomea after the war to live with her other daughter, Pearl Lachs. There was also a son, Josef, who lived in Vienna and had an import-export business.

It was hard for me to even think about quitting school. All of my friends were in school, but my father said "enough." I was dependent on him and could not support myself. School cost money and the arguments led to nothing until I had no choice and just had to cut everything with my father. My father was ultra-orthodox and his way was too strict for me if I wanted to socialize with the friends my age in Kolomea. At that time, there were circles and organizations; fraternal, social and political. There were all kinds, from ultra-right Zionist to ultra-left Socialist, about which my father did not know and did not want to know. It was really very hard, in fact, impossible, to give in to my father. So, I decided to go my own way instead of losing all my friends. It was better to be disassociated from my father and join a Zionist organization fitting my ideal. I had to look for a job in order to be able to pay tuition in commercial school and buy some clothing. My father would not pay for non-Chasidic clothing, so, all of a sudden, I was on my own. I still had room and board in my parent's house, but no place to go. Some of my friends went to study abroad. I couldn't even afford to go to a movie.

At last, I took a job in a wholesale textile store where I worked 6 days a week and long hours. But I made enough for tuition and some clothes. In my free time, I tried to read anything I could lay my hands on. I thirsted for knowledge, but could not afford to buy a book or go to school. But, I had good friends. Practically all of them were upper middle class and went to Gymnasium and were members of the general Zionist organization where I also belonged. There I associated with a better class of people. The older members were mostly established doctors, lawyers, or teachers. All of them were educated and in the evenings, there were lectures on every subject, not only Zionism. Those lectures filled, more or less, the gaps in my knowledge in other fields of general information. I rose to leadership in a youth organization and soon became a teacher of Hebrew and Jewish history. But, my father wanted no business with me.

Memories of My Father

My father was a self-made man. His father lived in Chernowitz and his name was Eliezer. My father's mother was named Pearl and she died very young. He said she was 32 years old when she died and she left four children. Upon her death, Eliezer left Kolomea for Chernowitz. The four children were placed in the care of a cousin, Chaye Ettie. She had six daughters of her own. I still remember her, but not her daughter's because they had emigrated to the USA. But, one daughter lived in Romania.

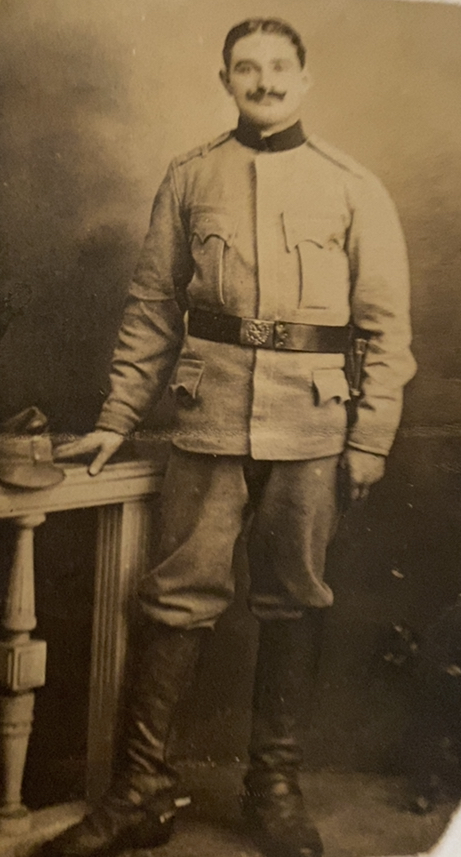

Besides Jewish education, my father was totally illiterate until he was drafted into the Austrian army under Kaiser Franz Josef. In the army, he learned to read and write and was promoted to be an officer of the rank of Zugführer. He served in the bodyguard brigade of the Kaiser in the castle of Schönbrunn near Vienna for six years. I still remember the picture of him as an officer on a white horse in a beautiful uniform with white gloves and a Kaiser beard. We were all proud of him when we saw that picture and the document of his honorable discharge. But, he had a rough life growing up as well as in the army. He raised us with military discipline, and we had it very hard as kids. In the middle of child play, if one of us just got wind, "der Tate geht" [father is coming] everything broke up and every one of us looked for a place to appear as innocent as possible. He would never give in on his principles, wrong or right. When it came my turn to venture into adulthood, the problem was the same with me as with all the other children. So, the only way was to break away like my older brother Gershon did. My sisters were in the same position. They could not go to dances or dress in short sleeves and so on. So, I tried by myself to learn from everybody and from everything. But, when it had to cost money, I could not afford it.

And so it went on until my father got sick one day in September 1930. It was the Jewish New Year, Rosh HaShanah. He went to visit my older married sister Pearl. She had three lovely children, two girls and a boy, Rose, Amish, and Saul. They lived in a just newly furnished house on a lot where our old house used to stand before it was destroyed in WWI. My father gave the lot to my sister and helped financially to build the house. That day, he felt like he had a cold, but when he sat down, he couldn't get up anymore. When the doctor came, he found his lungs were infected and he had a very high temperature. He gave him medicine and said he should stay in his bed. Otherwise, it would be very dangerous for him at his age. We really did not know how old he was. In the old days, it was the Chassidic tradition not to register their children when they were born in order to avoid later military service. That could lead to violation of Jewish religious law. But, it was a violation of governmental law and was punishable just like desertion from army service. My father was captured and therefore had to serve a punishment of twelve years in the military. He served only six years because he was a very outstanding, disciplined soldier. So, we knew his age only by his discharge documents. Based on that, he was 66 years old. He never had a birth certificate. How old he really was, nobody knew.

He was lying ill in my sister's house and the doctor came every day. He refused to take the medicine and said to the doctor in an argumentative way to let him die, the time has come. He spoke to the doctor in German saying, "stören Sie mir nicht die reise" [don’t stand in the way of my journey]. From day to day, he got worse. He insisted we call the Rabbi over. The scribe, Berele Leifer, was also called and my father dictated his last will to them. His last will was to give 500 to the Talmud Torah because that was the only school he attended where he learned about Judaism and had other Jewish education. The rest of his money was given to my two sisters in Kolomea, as they were still single, but not before a certain amount went to the poor in the city. When we protested that he gave away too much to the poor leaving his family without income, he said to call them to the Jewish Rabbinical Council after he's gone to negotiate a change. He himself would not change.

And so he said it was his time to go because in the Bible, it was written by the Patriarchs that when they came to the age of their fathers, they died. He considered himself at the age of his father so it was his time, but how old he was, we never knew. And so, he died after midnight, on a Saturday, the eleventh day of Cheshvan 1930.

Memories of My Mother

And now, let me say something about my mother. But before that, I must say that I never was close to my father. I never would confide anything to him. There always was a distance between all of us and him. But, to this day, I cannot explain why I felt such an emptiness after he was gone. I just felt a big loss and alone, even though I was all but abandoned by him. After he died, I felt admiration for him. I was proud of him, and I still am to this day.

My mother was entirely different and the opposite of him. She was born in a little town ten kilometres from Kolomea. She was the oldest child and had ten brothers. Her father, Aron Rosenkrantz, and her mother, Chana Luchs, were middle class people. They had a good, decent life when her parents moved to Kolomea. She said she was 13 years old at the time and she never felt like a real "Kolomeir." We all loved her very much because she was a devoted mother dedicated to her children without exception. Remarkably, she was totally illiterate. She could not even write her own name, but she could read very well from the book printed in Yiddish called the "Tz'enah Ur'enah” [the woman’s Bible]. She also read fluently from the “Teitl (sp) Chumash” [stories from the five Books of Moses], printed in Yiddish. Interestingly, her Yiddish materials were mixed with German expressions and a lot of Hebrew words. She could also read the prayers in Hebrew, but she was otherwise illiterate and ignorant of everything else.

However, she was smart and had great understanding. Every child confided their problems to her and all of us had confidence in her, unlike our father. She was married to my father when she was exactly twenty years old. He must have been much, much older because he was done with military service. She always said he was a very nice-looking man. Her girlfriends always said about her that she was a very beautiful girl. But, the way I knew them, both looked to me like they were past middle age without teeth. They had salt and pepper grayish hair. We all loved our mother very much and we respected our father very much. The difference was that she was a very devoted mother and earned our love while we respected and feared our father. I never felt any love for my father, only fear, and I respected him out of fear, not out of love. We all had confidence in our mother and felt her devotion as mother to all her children

Family Life

My mother had 13 children who were born before and after WWI, but

some of them died as children before that war. In 1914, I was

entering my sixth year of life, when WWI started. My younger

sister Friedel was just born. We all lived in a big house that

my father bought just a couple of years before the war started.

We all lived in that house except for my oldest brother Gershon, who

lived in a bachelor's apartment in the center of the city.

Gershon was in business for himself and was very prosperous. The

rest of the children lived with our parents in that big house on the

Sobiesk Str. The children were Pearl, Yetta, Blanche, Esther,

Shaindel, me, and Friedel.

In the Fall of 1914, my father went on a business trip to Hungary,

which was not far from us in the Carpathian mountains. Just

then, the war broke out and very quickly Kolomea was occupied by the

Russians. My father could not come back for the whole

winter. We had to leave the house because it was in the main

thoroughfare where the armies had to pass by. Plundering and

rape was a daily occurrence. We moved in with my brother Gershon

in his bachelor's apartment which was located in the center of the

city. Therefore, it was safer from the plundering and rape of

the invading army. The Cossacks were very antisemitic and

beatings and taking hostages of decent, defenseless citizens took

place almost every day. Forced labor was also a daily occurrence

and the victims were mostly Jews. But still, life had to go

on. Some Jewish officers in the Russian army intervened and life

went on even under those harsh conditions. And so we lived

through all those harsh and rough conditions throughout the whole

winter.

An offensive by the Austrians started around March. By the

middle of March, the Austrians stormed the city and took it over, but

not without casualties. A week later, my father came back from

Hungary. We tried to normalize our life despite the fact that

most of the houses in the center of the city were demolished by the

bombardment from heavy artillery. In the middle of the summer of

1916, a total mobilization began. My brother Gershon was taken

and we feared that my father could also be drafted. My mother's

two youngest brothers were drafted by the Austrians and two of her

other brothers were drafted into the German army. Those

brothers, Ignatz and Bernard, and Bernard's son Max, were German

citizens and lived in Germany.

Around July 1916, Kolomea was again taken by the Russians. As I

mentioned before, we left the city before the Russians came

back. My parents and I, and my sisters Shaindel and Friedel,

left the city with our own two horses and loaded wagon.

Traveling throughout the Carpathian mountains in the direction toward

Hungary, we later arrived in Sighet. There, we sold the horses

and wagon and boarded a freight train for refugees which later brought

us to Moravia. There we lived as refugees for the next two and a

half years. I went to German school until I finished the third

grade. I was an outstanding student; the best in the

class.

In the beginning of 1918, we came back to Kolomea and found both of

our houses in ruins. It was very hard to get living space.

Naturally, my father lost his business and we did not know yet to

which government we all belonged. In the meantime, Kolomea was

occupied by the Romanian army. Nobody knew what the future

status of the Kolomea area would be. At that time, the

Ukrainians organized a temporary government in Lvov which included all

of eastern Galicia. I became a student in the second grade

because I didn't know how to speak Ukrainian. That didn't last

long. In the beginning of 1919, it was decided that Kolomea

would be a Polish city. As I mentioned earlier, the Polish army,

under Gen. Josef Haller, took over the city from the Romanians.

Pogroms broke out and many young Jews were killed. The whole

economy was in shambles. The whole area became the corner

triangle of Poland. In the immediate area there were four border

lines: The Russian border, the Czech border, the Romanian

border, and the Hungarian border. All the commercial activities

were cut off.

Poverty, hunger, and epidemics became the order of the day. The

elderly and the very young died like flies. Luckily, the Joint

Distribution Committee opened kitchens. But, no future for the

young was in sight. All of a sudden, we received a letter from

the US from my father's youngest brother Leib Stahl. In the

letter, he asked if my father was still alive because he heard that

one of his two brothers had died. He did not know which.

The truth was that his older brother Abba died in Berlin during his

stay with his daughter Ettel on his way to Palestine. In our

letter back to the US, we let our uncle know about the whole situation

and that it is very hard to manage under the conditions. In the

next letter we received, there were two tickets for Yetta and Blanche

to come to the US. A week later, a ticket also came for Esther

to come to the US. The same year, all three emigrated to New

York with a lot of other people who also had relatives in

America.

For us, it was very difficult, as it was for them, to get used to our

parting. But for the next twenty years, until the day the second

World War broke out, they in America were a tremendous help to us from

time to time. They sent us packages with used clothing.

For every holiday, we received money in dollars that we exchanged for

our money. Sometimes, the exchange gave us more than double the

amount of our money for those dollars. This was a great help for

our survival up to the start of WWII. The antisemitism from both

the Poles and the Ukrainians plus the poverty among the Jews made us

feel so hopeless that everybody was resigned to despondency.

Very few could emigrate to Palestine because of the certificate

quotas. So, almost by miracle, we survived from one day to

another.

Military Service and My Last Vision of Kolomea

When the war broke out on September 1, 1939, most of us were taken to

the Army for about a month or so. That was how long it took

until the Soviets occupied almost half of Poland. There was

chaos and nobody was thinking about what would be in our future.

The city was full of refugees from all over. Everybody was

unemployed. With no jobs and no work, the black market was

booming. Everything was bought or sold on the black

market. It took almost a full year until everything got organized

into cooperatives. Little by little, everybody got a job and life

started to normalize. A lot of refugees were sent away to inner

Russia. We thought life had returned to normal. We felt

pretty secure with our work, and also as Jews. Antisemitism was

seemingly non-existent.

But, the years between the two World Wars was a miserable

existence. Young people could not get married because of

economic reasons. There was no possibility for jobs or any work

to make a living for the Jews. For instance, I courted a girl

for many years. I was very much in love with her when my father

died in 1930. I felt helpless and hopeless. But as a young

man, I had normal feelings. I went out with many girls, but I

could not think of marriage because there was no possibility of making

a living in Kolomea for a Jew. Between the two World Wars, there

were strong Zionist youth movements, but emigration to Palestine was

limited by quotas, and so it was everywhere else. We were just

trapped with no hope for a future whatsoever. When the

Bolsheviks took over at the end of 1939, we thought that would be our

life, but it did not last. On May 14, 1941, I was called up in

the reserves for the Red Army. It was to be for only 6 weeks,

but I never returned home ever after.

Just about a half year before the war broke out in 1939, in March, I

got married to a girl with whom I went out for about eight

years. I loved her dearly but, could not marry her because of

the economic situation. I had no means by which to make a

living. The jobs that I had as a clerk in a wholesale

manufacturer store did not pay enough to support a family. My

fiancée also worked, first for a tailor of women's dresses. After

that, she worked for her older sister Miriam who had just gotten

married to a wonderful, handsome man with a good education. He

was not from Kolomea; he was from Rovzo (sp), a little townlet on the

Russian border. That townlet was closed to the public as it was

a military stronghold for the Polish border police. Therefore, it had

no resources from which to make a living there. Peddlers just

used to travel all over Poland to sell Kilims, handmade wool divans

for floor and wall mural covering, and fillet drapes, also

handmade. Those were used as window coverings to decorate the

houses of the officers of the Polish army and officials of the

government. The peddlers would be paid in installments.

That was the primary trade of the Kolomean Jewish population, male and

female, young and old, between 1930 and 1939. But, it was very

hard to make a living that way under such miserable conditions.

Don't wonder why I could not get married sooner to my love, Anne, or

as she was called, Chancia. She was beautiful, intelligent, and

gifted, but that was our luck in Kolomea. I was not the only

one; this was the fate of all. At last we got married in March

1939 and we moved into a three room apartment that we fixed up. The

apartment was in one of the two houses which my wife and her sister

inherited from their father. We had new custom made furniture

made to order to our taste. We both owed the money to pay for

the furniture. For the last six to seven years, we lived right across

the street from my mother who lived with my youngest sister

Friedel. My sister had just gotten engaged to a very nice fellow

from a nearby townlet, Delentyn (sp). About six months after my

sister's engagement, the Germans attacked Poland and the Red army

occupied Kolomea. All of the Jewish people were relieved, even

though it was very hard to live during the early part of the

occupation. But somehow we survived that awful time. Little by

little, it started to settle down. A lot of refugees went back

to their homes. A lot of them were sent away to Russia. We

got settled in jobs and things started to normalize, more or

less. At least, we were not under the Germans.

On May 14, 1941, I was called up into the Red Army, even though I just

got out of the Polish army in January 1940. I was only supposed

to serve for maneuvers for 6 weeks. But, on June 22, 1941 the

war broke out and on July 1st we left Kolomea and we kept on

retreating. The war broke out on the 22nd of June 1941. The Red

Army retreated from the advancing German forces on the 1st of July

1941. I was wandering in and out of the army for the next ten years

until 1949. On the 7th of July 1949, I arrived in the US as a

surviver refugee.

|

|

|

|

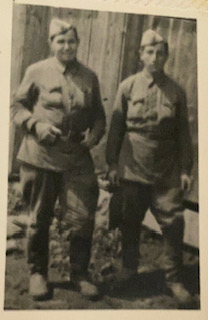

| Aron Stahl’s brother Gershon in Austrian military uniform (circa 1915). | Sisters Esther, Blanche and Yetta after arrival in the US (circa 1920). | Aron Stahl (left) in Russian military uniform with swollen, bandaged right hand after partial amputation due to shrapnel wound (circa 1944). | Aron Stahl passport photo (circa 1949) prior to emigration to US. |

|

|

| Aron Stahl’s family in Kolomea - standing top row (l-r) a Talmudic student, sisters Pearl and Blanche; seated (l-r) sister Shaindel, mother Ettel, sister Esther, father Izak, sister Yetta; Aron on floor with sister Friedel on low bench. Photo (circa 1920) taken before Blanche, Yetta, and Esther emigrated to the US. | Ladies sewing lace Fillet drapery (circa 1928); Aron Stahl’s wife Anne Stempler seated second from right. |

|

|

| Zionist Youth members (circa 1931); Aron Stahl pictured top row, fourth from the right. | Aron Stahl with wife Luba (née Bodgas) holding infant daughter Barbara with sons Murray and Stuart on lap (circa 1960). |

This page was created by and maintained by

Alan Weiser until 2018. Now maintained by Sheryl

Stahl. Suggestions are welcome. Updated Spring 2019. Copyright

© Alan Weiser and Sheryl Stahl 2023

Find more KehilaLink pages at https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen,

Inc., a non-profit corporation. If you feel there is a benefit

to you in accessing this site, your JewishGen-erosity is

appreciated.

http://www.jewishgen.org/JewishGen-erosity/