Enter Text

Coat of Arms

of Borysław

Geography

History of the Jewish Community in Borysław

The Tyśmienica River running through a landscape of derricks

A "koshere" or ozokerite mine

The Town

The famous Borysław Most (bridge) over the river Tyśmienica was in the middle of the town. It was also known as Baraba Most (Bridge), because homeless and unemployed people, known as baraba once used the banks of the river under the bridge for their encampments. All the main roads in Borysław originated at the bridge. Ulica (Street) Pańska, later re-named Kosciuszko Street, began there and continued west. To the east of the bridge, Drohobycki Trakt (Drohobycz Trail), later changed to Mickiewicza Street, led to the villages of Hubycze, Dereźyce, and Drohobycz. To the north, Zielinski Street led to Wolanka, Tustanowice and further to Truskawiec and Stebnik.

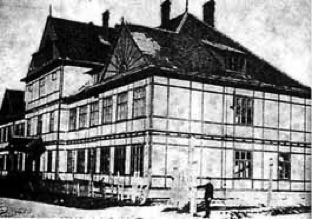

Pańska Street: Like all the roadways the street was unpaved with crude

boardwalks providing the only paths through the yellow, oily mud.

Landholdings in Boryław

The earliest history we have of the development of Borysław concerns three Polish landlords: Pan Kropiwnicki, owner of the village of Borysław, Pan Nahujowski, owner of the lands in Nahujowice and Kropiwnik, Pan Andrzej Drozd, owner of the properties in Tustanowice, and their lease holder, David Lindenbaum. Eventually Lindenbaum, through unusual,romantic circumstances and the unpaid debts of the owners, became the legal owner of all these properties.

Gymnasium (Secondary School) in Borysław

.

Life in Boryslaw

At the end of the nineteenth century, when many of the small Jewish holdings had been consolidated under foreign ownership, the new managers refused to hire Jewish wokers. Many of the Jewish labourers who had depended upon the petroleum industry were now unemployed and starving. Their plight was presented to the World Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, where letters from 4,000 people or 765 families were received declaring their desire to escape their desperate situation and emigrate to Palestine

After the congress, the Viennese Labour Zionist, Saul Rafael Landau visited Galicia and vividly depicted the conditions of the Jews of Borysław.

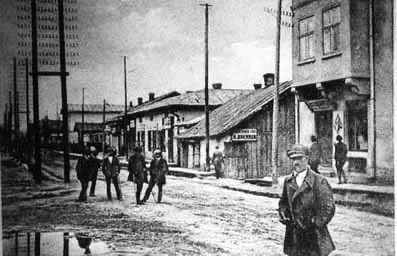

The smal village of Borysław changed rapidly with the discovery of crude oil and ozokerite (mineral wax). Borysław is one of the few places on earth in which this hydrocarbon is found in large quantities.

The ozokerite industry developed first. Because the initial capital investment was small, a rope, a shovel, a pail and a winch, many small entrepreneurs started wax mines, which they called kosheres from the Polish word for barracks. Jews,

who were forbidden from owning land and had few employment opportunties, dug shafts in the earth by hand. They would rent a piece of land or share the profits with the landowner. With primitive methods, they washed and processed the wax for use in the making of candles and soap. The process was labor intensive; it provided employment for many men and women in the area and attracted many Jews from other areas. Some Jewish families prospered from the enterprises and began to build large companies in candle and soap manufacturing. (See Petroleum History in Galicia for a more complete description of the industry.

Life in Borysław revolved around the petroleum industry. Bythe 1880's the landscape, which earlier had been pocked with shafts dug by hand, was cluttered with oil derricks between which ran rivulets of dirty ground water iridescent with oil slicks pumped from the shafts. The air reeked of oil and paraffin. The streets were unpaved with crude boardwalks providing the only paths through the yellow mud.

House in Borysław

The few Jewish families who became wealthy from the ozokerite and petroleum industries moved their families to more elegant homes in Drohobycz. The labourers lived in houses made of wood; many had sunk below the street level. Built closely together, they were a tinder box for the frequent fires that ignited in the puddles of oil found throughout the town. In 1908. one conflagration in nearby Tustanowice burned for four months.

Most of the Jews of Borysław depended directly or indirectly on the petroleum and ozokerite industries for their livelihood; however, these workers were treated very harshly. in the early days they were hired only on a daily basis and paid a meager wage. The shafts in which they worked were unstable; the machinery which lowered them down, primitive. They had neither safety lamps nor gas masks. When inspectors were finally engaged to enforce even the simplest of safety measures, they had to have police protection to protect them from the fury of the mine owners. No one recorded the names of the workers. When one died on the job, his body could easily have been buried in a shaft, left in a field, or wheeled through the town in a cart until the body was claimed.

Łepaks collecting oil from a ditch

The Jewish Population of Borysław

Panksa Street, the main thoroughfare in Borysław. The photograph above comes from the Wilhelm Russ studio. Russ was a prominent photographer from Drohobycz who documented the oil industry and photographed many of the Jewish familes in the Drohobycz area. His son Gustav, who trained in his studio became a famous, innovative photographer in Poland, acknowledged with many awards and distinctions.

Another view of Pańksa Street by Wilhlem Russ.

Borysław lies (5.9 miles (9.6 kilometres) south-west of its historic sister town Drohobycz and 120 kilometres sout-west from the provincial and regional capital Lwów (Lviv) in the valley carved by the Tyśmienica River. The Tyśmienica is a tributary of the larger Dniester River and its smaller tributaries, called by the local people Ponerlanka, Ropianka, and Potok, flow in the valley. Borysław is separated from neighbouring oil towns like Schodnica by the High Beskid Mountains.

To the south of the bridge, a road leads to Potok, Bania Kotowska, Ratoczyn and Popiele. Debra, Łoziny, Nowy Swiat, Moczary were known as the inner city districts of Borysław and were synonymous with unemployment, poverty, and superstition.

The Business Directory for Poland of 1929 gives a snapshot of Borysław in that period. It had a police station, a municipal office, a high school (gymnasium), a public hospital, schools for drilling and for the training of industrial workers, an electric and a geological station, a Chamber of Commerce for the Petroleum Industry, and many associations for professionals and workers in the petroleum andozokerite industries. Its main industries are listed as petroleum, ozokerite, and the and the manufacture of drilling machinery. It is called the centre of the petroleum industry of Poland.

Just prior to World War II, the heirs of the Lindenbaum holdings, collected twenty percent of the gross value of all oil from their properties, in addition to 0.3 kg of wheat for every square metre of their property occupied by the owners of the oil wells. They alsoreceived the income from the oil refinery in Hubicze near Borysław from the sawmills, and from numerous other land and forested properties not used directly in oil exploration

This area of modern western Ukraine is known as Prikarpatye or Podkarpatye (literally, near the Carpathian Mountains). From the west, the town is framed by the splendid view of the eastern branch of the Carpathian chain covered by evergreens on the High Beskyd (Tsukhovyi Dil). Borysław itself is 343 miles (552 kilometres) above sea level. Numerous mountain streams flow among the rolling hills. The scenery is similar to Vermont in new Engliand.

Until the mid nineteenth century, Borysław was a quiet village outside of the larger market town of Drohobycz, the capital of the Austrian Administrative District, and the seat of justice and local government. With the discovery of oil and the development of the ozokerite and petroleum industries, Borysław began to absorb the surrounding villages of Upper and Lower Potok, Upper and Lower Wolanka, and Ratoczyn. In 1933, the larger neighouring villages, Schodnica, Tustanowice, Bania Kotowska, and Mrażnica were incorpoated into Borysław. This made the town the third largest in area in pre-war Poland, after Warsaw and Łódz. Most of this area was occupied by the oil fields. Besides Drohobycz, other large towns in the area, like Sambor to the north-west, Mikolaiw, to the north-east, and Stryj to the south-east, are connected to Borysław by local roads.

Pańska Street in Borysław

View of houses in Borysław