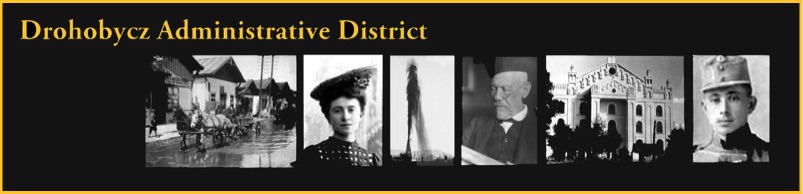

Israel (Srul) Liebermann (1845-1919) was the oldest of Hersch and Sarah Liebermann's eight children. Together with his father and a couple of his siblings, he was one of the more successful producers in the wax industry. A a complex and controversial figure, he is mentioned in several written testimonials from this period. His nickname Didik, which means “wild spirit of the forest, hinted at his personality. Israel Liebermann's immense success and his social status in town were diminished when he stood trial for having a competitor beaten up.

Israel Liebermann was married three times. He and his first wife was Chaja Donnenberg (1848-1868) had two children: Mina-Minchi (1864-1942) and Feiwel (Filip) (1867-1942). Following Chaje's death, Israel married Chana Waldinger in 1869. They had three children: Rozalia (m. Dr. David Lichtgarn) (1870-?); Maurycy (1873-1941) (m. Fania): and Judes (1875-1941) (m. Moses Marbach). Chana died before 1877.

Documents from 1877 show that Israel married Rachela Weingarten (1845-1928), the daughter of Leib Weingarten and Chane Henia Sternbach. Israel and Rachela had five, possibly six children: Marcus (Marek) and his twin sister Antonia, (1878-1942); Meilech (Michał) (1880-1942); Chaja-Tille (Tula) (b. 1881); Sara-Beile (Sala) (1882-1941); and Joachim (Karol) (1885-1943). Around 1911, Israel and Rachela moved to Lwów where a few of their children lived and studied. The members of the family were close. Many lived within walking distance from each other in the streets surrounding Halicki Square where Israel and Rachela lived in Walowa Street.

Israel died in July 1919 at the age of seventy-four; the cause was said to be old age. Israel was quoted as saying that after the fall of the emperor, there was no reason to continue living.

All of Israel's children accept one, Rozali, who died prior to the onset of the Second World War, perished between 1941 and 1943 in Lwów, Bełżec, or the towns surrounding Lwów. Some were murdered at the hands of the Nazis; others died of hunger or untreated ailments while in hiding. The same fate befell their spouses and some of their children. Those who survived made it to safety in Western Europe, the USA, and Israel. A small representation of the family remained hiding their identity in Poland.

Rosa Liebermann, daughter of Israel's second wife Chana Waldinger, married Dr Jacob Lichtgarn, who studied medicine at the University of Vienna and practiced in Borysław. They had two children Anna Blanka (b. ca 1904) and Dolek (b. 1908)

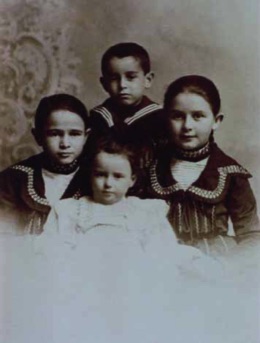

Rozalia (Rosa) Liebermann and Dr David Lichtgarn

with their children: Anna Blanka (b. ca 1904)

and Dolek (b. 1908) in 1908

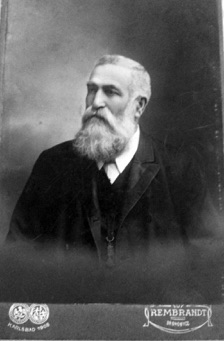

Left: Mina Liebermann-Ashkenazi, ca 1940

Mina, Israel and his first wife Chaja Donneberg's first-born, was a toddler when her mother died of typhus; she was raised by Chana Waldinger Israel's second wife, and then by his third wife Rachela Weingarten. In 1884, Mina was betrothed to Lazer Aszkenazi, a divorcé. The couple had five children: three daughters and two sons: Abraham (1897-1974), Malwina (Mania), (1889-1967), Albert Marcel (Maciej) (1841-1949). Laura (Lusha) (1897), and Sonia (1901). When the First World War broke out, the two sons were serving in the Austro-Hungarian Army; the rest of the family escaped to Vienna. In 1919, Lazer Ashkenazi died in Vienna. Mina was left penniless, as the family had invested heavily in Austrian war bonds.

By the mid 1920s, the three daughters of Mina and Leisor Ashkenazy were married to German citizens and living in Germany.

Mania (1889 – 1967), Mina and Lazer's second child and oldest daughter, married Paul Stern in 1910. Paul Stern was the managing director of a concern of flourmills in Silesia. By the early 1930s, the family was living in Berlin. They had two sons and a daughter who had been born in Breslau: Henry, Walter (1918), Ruth (1922-1990).

On June 15, 1938, Paul Stern was arrested and was sent to the concentration camp at Buchenwald. He was forced to sign over ownership of the flourmills and agreed to leave the country as a condition of his release.

Paul was released from Buchenwald on September 8, 1938. He, Mania, and their daughter Ruth left Germany for England later that year. After living in Gloucester for seven years, they emigrated in the mid 1940s to Kansas City, which was, at that time, the centre of the flour milling industry in the U.S.

By this time, their older son Henry had become an American citizen and was serving in the U.S. Army. His commanding officer prevailed upon Harry Truman to sign the affidavit required to admit his parents and sister to the US.

Mania Ashkenasy-Stern

Details of Henry Stern's career are unclear, but it seems that he may have been initially involved in the flour milling business in the US, and then pursued other business interests in the U.S., Switzerland, and Australia. He died in 1996 in Berlin

The younger son Walter had left Germany at age 15 to attend boarding school at Badingham College in Surrey, England. He went on to attend Oxford University and had a long career at British Petroleum in their petrochemical business, living the rest of his life in London, where he died in January 2015. Neither Henry nor Walter ever married. Ruth, Paul and Mania's daughter, came to the U.S with her parents.

Sonia (1905 - 1988), the youngest of the Ashkenasy children, was married briefly in Vienna to Erno Stern whom she divorced after the birth of her son Robert (1926-2006). Following the divorce. Sonia moved to Breslau where her two older married sisters lived. There she met Hans Petersdorf (1899 - 1988), whose family owned Petersdorf's, a large department store. Hans and Sonja married in 1928; their son Rudolph (Rudy) (1928-2011) was born in 1930. At Sonia's insistence, the couple left Breslau for the U.S in 1936, and their children followed in 1937.

Making decent living in the U.S was a struggle for Sonia and her husband. After a few attempts to establish themselves in New York, Connecticut, and Saint-Louis, the family ended up settling in Los Angeles in 1948, where Hans worked as a travelling representative for various women's fashion manufacturers and Sonia worked for a fashion house.

Following the unexpected death of Wolfgang, the family left Breslau for the United States in 1938. It was Lucia who urged the family to leave. Joseph, who was deeply attached to the German culture in which he was raised and in which he thrived professionally, did not believe that the threats made towards Jews would amount to anything.

Sonia Ashkenasy-Petersdorf

During those interwar years, Maciej developed his burgeoning business as a representative of the iron and steel company Rima Murani. Maciej was known in Lwów to have leftist political views, which did not curry favor with some people. Within the immediate family circle he was respected and loved as a dedicated son, brother, and a mentor for the younger generation.

On the eve of the Second World War, Maciej's mother Mina had come to live with him after all three of her daughters had emigrated to the USA. By then an elderly lady, Mina had suffered a hip injury that left her limping. Maciej nursed his mother in hiding until she died near the end of 1942. He also sheltered the two children of his brother Dolek and their mother Valeria. During the war he hid and supported other relatives until he could do so no longer.

At a later stage in the war, Maciej, who had been hiding in the centre of the city all along, was denounced and had to leave Lwów. He went to a village where a Polish family hid him, his brother's wife, and the two infants. They stayed there until the Red Army liberated the area.

Marcel (Maciej) Ashkenazy (Czarniecki) (July 30, 1927)

Adolf (Dolek) Askenazy and his son Léon (Bouvier) in 1938

Dolek Ashkenazi was married twice. With his first wife Regina Reinfeld, he had a son Léon, born 23 September 1926. His second wife was Valeria Folta. with whom he had two sons: Piotr (b. 1941) and Maciej Jr. (b. 1942). Dolek was murdered by the Gestapo in the winter of 1942, before Maciej, his second son with Valeria Folta, was born.

Initially, Maciej returned to stay in Lwów and took a management job in the George Hotel. When the “transfer” happened, the mass exchange of Poles from Ukraine to Poland and Ukrainians from Poland to Ukraine, he and his new family moved to Poland where he first settled in Kraków and later in the area of Wrocław

Upon moving to Poland, he was registered as Maciej Czarniecki, married to Valeria Folta, and father of two. Thus any traces of his or the children's connection to their Jewish origin were erased. In order to establish a new life, he also chose not to use the old local business contacts he had before the war. He did this because he believed he would be endangering his two nephews and their mother, if his Jewish identity were discovered.

At first, Maciej took a job in the new Polish housing authority in Silesia. Post-war Poland was a rude awakening for him. Dissatisfied and critical of the way things were managed, he got into arguments and lost his position as a manager. A string of other attempts to establish satisfactory employment did not go well. At one point, Maciej was framed by two other survivors who were struggling to gain position and power within the new system. In 1947 Maciej was arrested and sent to prison from which he emerged severely ill with tuberculosis. He spent his last months between a sanatorium and his home. He died in 1949.

Valeria Folta and Maciej Czarniecki (1949)

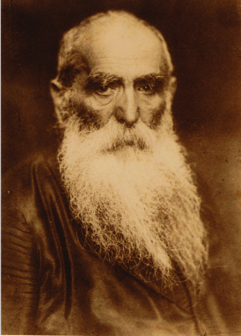

Filip, Israel's second child, was an infant when his mother Chaja Donneberg died in December 1868. Like his older sister Mina, Filip was raised together with the younger siblings who were born to Israel by his second and third wives. Filip left Borysław when he was seventeen to serve in the Austro-Hungarian army. By the time he returned to Drohobycz, his father's business was in decline. In 1890, when he was twenty-three, he was betrothed to Chaja–Sarah (Babbeta) Lukaczer (1856-1926), a widow eleven years his senior . Babbeta had inherited a small factory that produced alcohol and yeast in Knyahiławów (today Ivano-Frankivsk).

Filip and Babbeta ca 1896

Liebermann Children c. 1900

Filip and Babbeta's factory grew immensely between 1890 and 1914. The factory's archival documents and photographs of the family tell a story of success. During the First World War, the factory was severely damaged. At the end of the war it was rebuilt with the help of the factory employees and continued to grow and flourish.

The factory was considered one of the largest producers of yeast in Poland. Its yeast was sold domestically and exported overseas. Both Filip and Babetta and later their children were actively involved in the public affairs of their town. They donated money to support social causes: an orphanage and a hospital. They also donated funds and were directly involved in developing a program of vocational schools for young men and women.

The house in Knyahinin

Babetta died in October 1926. Filip continued to develop the factory with his son Benno as partner, his brother Mauricy as manager, and his two sons-in-law, Emanuel (Milek) Sperber and Henrik Kupfermann, in various roles. In the years between the two world wars, Filip served on the boards of several nonprofit organizations. He was a member of the town council and supported the local Bnai Brith lodge, among many other charities.

With the rise of anti-Semitism in Poland in 1933, Filip became aware of the looming danger for Jews. In 1934, he resigned his position on the town council and declined to carry on providing financial support for his local chapter of Bnai Brith. Instead, he proceeded to support causes that he believed might address the anticipated danger. In 1934, he visited Palestine where he purchased land and explored investment opportunities in 1936.

Benno, Nelly, Jenny, Filip, Cilly in Jaremce 1928

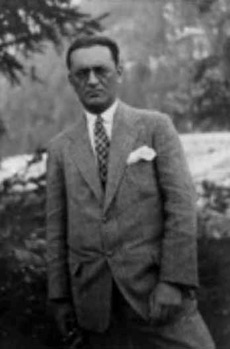

Filip Liebermann ca 1934

By the time Benno was born, Filip and Babetta were running a thriving yeast and alcohol factory. The two older sisters, Jenny and Cilly, were sent to finishing school in Austria; Benno and his younger sister Nelly were brought up at home by nannies and German-speaking private tutors.

In the summer of 1914, Benno graduated from high school in Stanisławów (Ivano-Frankivsk), and was immediately drafted to the Austro-Hungarian Army, where he served until the end of the First World War.

Benno 1914

Notes

* Paul Engelmann, a friend of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, was born in Olmütz in 1891. He studied wih the modernist architect Adolf Loos in Vienna and was also Karl Kraus' private secretary. In 1934 he emigrated to Tel Aviv in where he died in 1965.

** https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanisław_Vincenz (Polish)

*** https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sursock_family

Robert Petersdorf: Bob, Sonia's oldest son, was an internationally known infectious disease expert. He was professor of mediciine at Harvard, later vice chancellor for health sciences and dean at the University of California at the San Diego School of Medicine, and later president of the Assoication of American Medical Colleges.

Rudolph Petersdorf: Rudy became a lawyer. He worked for Capitol Records, Desilu, and Universal Studios.

Back in Poland, Filip donated land and resources to establish a farm where young people were trained to work in agriculture in anticipation of their emigration to Palestine. He donated money to buy an airplane for the representatives of the Zionist Movement, so that they could reach communities in Poland to warn them of the looming danger; and he gave money to purchase ammunition for the Polish army.

In 1929 Filip, embarked on his last major project in Poland. Together with his friend Paul Engelmann,* a talented architect, and with the support of the city of Stanisławów, a small neighborhood was designed and built in Knyahinin, near the factory. The houses that they built were well-lit, thoughtfully designed, modern dwellings. The homes were small but felt extensive. Each home had a small garden in the back of the building.

In the early 1930s, as anti-Semitism was becoming more and more noticeable in central and eastern Europe, Benno directed his energy into issues connected to the situation. He became involved in supporting a farm near Stanisławów, which was established to teach agricultural skills to young people who were planning to make emigrate to Palestine.

During the years 1934-1935, Benno, together with his friend Stanisław Vincenz** and a wider group of authors and journalists, concentrated his efforts in publishing essays opposing the anti-Semitic tone in the media. Benno and other members also visited churches during Sunday sermons where they were allowed to talk to congregants, hoping to change their attitude. This operation was clandestinely financed by Bnai Brith in Galicia.

In May 1933, Benno and first wife Eli (née Brecher), whom he had married in Vienna in April 1930, traveled to Palestine. While on their trip, they stayed in Tel Aviv, visiting various friends who already lived there. They also examined different types of settlements in Palestine. Eli documented what they had seen both in words and photos.

In 1936, Benno and Filip purchased land and a home for the extended family in the western Galilee in Palestine. The property was located in an area named Ein Sarah, two kilometers south of the newly founded city of Nahariya. The home was purchased from the Sursok*** family, a Greek Orthodox family originally from Turkey, who were landowners residing in Beirut. The house had been their summer home.

Benno returned to Poland to continue managing the operations of the factory. During this period, attempts were made to transfer some of the family's wealth out of the country, unfortunately with little success.

The House in Ein Sarah in the 1940s

Benno and his family lived first in Haifa, where his older sister Cilly and her family were already living. The home they had purchased in the Galilee was poorly insulated and had no hot water. By this time there were no funds to undertake major renovations of the house.

In the mean time, a citrus orchard was planted on the property and a herd of cows was bought, and the land was worked by hired hands. The extended family gathered there together with friends during weekends and summer breaks. Soon after he arrived in Palestine, Benno separated from Eli. A couple of years later, in the summer of 1943, Eli disappeared. The remains of her body were eventually found in the Carmel Mountains. It turned out that she had been having an affair, and when she tried to end the relationship, her lover lured her up to the Carmel Mountains, killed her, and committed suicide.

Benno ca 1940

Following his release from duty he returned to his studies. In 1923 he completed his Ph.D. in business and economics at the University of Frankfurt.

Benno in Austrian uniform

Upon returning to Stanisławow, Benno assumed an active roll in managing the family factory with his father. He also became involved in supporting cultural and educational initiatives in town. During those years, Benno dedicated much of his time to developing vocational programs for both young men and women, with the hope that such tools would improve the likelihood of a stable income for the younger generation. He also supported some of these institutions financially when they failed to thrive. Through his friendhsip with his cousin Hermann Liebermann, the lawyer and politician, he met Hermann's lover, the psychoanalyst Helene Deutsch, who had studied with Sigmund Freud and founded the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. Possibly her influence inspired Benno's financeing the beginning of psychoanalytic training in Poland.

Mina (Minchi) Liebermann-Aszkenazi (1864-1942)

Mina Liebermann-Aszkenazi's Children and Grandchildren

Filip Liebermann (1867-1942?)

Filip and Babbeta had four children: Jeanetta (Jenny) (1891-1973), Cecilia (Cilly) (1893-1974), Benedykt (Benno) (1896-1950), and Aniela (Nelly) (1898-1989).

In 1934 he funded a clandestine operation in which his son Benno was actively involved, an operation in which Polish and Jewish journalists, philosophers, authors, and clergymen from Galicia took part, hoping to change the anti-Semitic climate of publications in the media and in Sunday church sermons

The factory was incorporated in 1935. It operated under the ownership of the Liebermanns until the outbreak of the Second World War, at which point it was nationalized by the government of the USSR when they took control of the area under the Molotov-Ribbentrop Agreement. It was taken over by the Germans after they entered Stanisławów in June 1941. The factory still operates today and is owned by the Ukrainian government. It produces vodka and other alcoholic drinks. It is still referred to as the Liebermann factory.

When the war broke out in September 1939, Filip chose to remain in Stanisławów. Both his son Benno and his daughter Nelly and her husband tried to convince him to leave, but he refused. Initially he stayed with his brother Mauricy and his widowed sister Ida. By then, his daughter Cilly and her family were already in Palestine. Benno, Nelly and her family left for Palestine soon after. Jenny was in Italy. Filip's official rationale for staying was that, being old, he did not want to impose himself on his children. Since his other siblings were in Stanisławów, Lwów and Drohobycz, it must have been hard for Filip to contemplate leaving, knowing that his siblings, with whom he was very close, were staying behind.

When the Red Army entered the town, they confiscated and nationalized the factory. Filip and Mauricy his brother were exiled to Kołomyja. They lived in Kołomyja, supported by the employees of the factory, who saw that they had food and enough money to buy wood to keep warm. When the German entered the area, Mauricy was arrested and probably executed soon thereafter. Filip lived in hiding and eventually died, some time in the summer of 1942, apparently of natural causes.

Filip Liebermann's Children and Grandchildren

Benno and Klara ca 19405

Right: Rachel Liebermann 1950

This trauma, coupled with the presumed death of Filip in occupied Poland, and the realization of the catastrophic fate that had befallen other family members and friends in Europe, affected Benno heavily. In 1944 ,he met Klara Schechter, who had come to Israel from the town of Ternopil, also in Galicia. They married in 1945 and moved to the house in Ein Sarah to live permanently.

Following the war of independence, as the country began functioning, the economy was depressed and the chances of creating a viable source of income did not seem promising to Benno. In November 1950, battling a bout of severe depression, Benno committed suicide

Abraham Adolf (Dolek) Aszkenazi (1886-1942)

Albert Marcel Aszkenazi (Maciej Czarniecki) 1897-1974

Mania Aszkenazi-Stern (1889-1967)

Laura Aszkenazi-Dienstfertig (1897-1974)

Sonia Ashkenasy-Petersdorf (1905-1988)

Benno (Benedykt) Liebermann (1896-1950

In 1942, following two years of schooling at Harvard, John enlisted in the American army. Since he spoke his native German and was fluent in French he was assigned to P.O. Box1142, a military intelligence unit that was set up to collect information from German and Russian prisoners of war. At the end of the war, John returned to Harvard to complete his B.A. Following graduation, he left for France where he obtained a law degree from the Sorbonne, after which he returned to Harvard to obtain a graduate degree in political science. After graduating from Harvard, he turned down a position with the CIA but accepted a position in 1950 with the European Economic Aid Committee of the Marshall Plan in Paris. The Paris tour was followed by a period of work in Belgium and later with the Economic Assistance Mission to French Indochina: Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. John found the work environment in the Marshall Plan exciting and stimulating. In his words, this was a place to learn about economics, finance, politics, and different cultures, and also meet brilliant people. While working in Paris, John met his future wife, Martine Duphenieux. They married in 1952.

While working in Saigon, John took his exams for the U.S. Foreign Service. He spent over thirty years in the service of U.S. State Department in various positions:

1956-1958 - his first diplomatic role - part of the economic section in the American embassy in Saigon. He also worked as a political officer in Vientiane, Laos.

1958 - he opened a consulate in Lome, Togo, East Africa.

1960 - he opened the first American diplomatic representation in Bamako, Mali.

1963-1965 - he was at the U.N. as an adviser to the French-speaking African delegations.

1965-1969 - in Paris, as partner to the Vietnamese-American peace talks.

1969-1970 - he spent a sabbatical year at the Center for International Affairs in Harvard. While there, John wrote a paper about controlled negotiations solutions, with reference to Vietnam.

1970-1972 - John was in Vietnam. Based in Danang, he was in charge of the American advisory effort made for Military Region One.

1972-1973 - John returned to Laos to play a vital role as mediator and catalyst in the negotiations between the Laotian Royal government and the Pathet-Lao, the Laotian rebels.

John Dean (Günther Dienstfertig) b. 1926

In Kansas, John completed his high school studies. His father worked as a bank clerk. Lucia was employed in a clothing store. While his parents struggled to find appropriate occupations in the new country, John immersed himself in school, learning about the new culture to which he was exposed, and making an effort to become part of it as soon as possible. He became interested in the history of the United States and read every book about American history and culture he could find. John said that he knew already then that he would want to serve, to give back to the country that gave him a home when he had to escape Germany. In 1940, at age sixteen, he graduated from high school. He went at Harvard where he received a scholarship. To supplement his income, he waited on tables in the evenings.

John Dean

September 1975 - Summer 1978 - appointment as ambassador to Denmark.

1978-1981 - appointment as ambassador to Lebanon. In 1978, Lebanon was in the midst of a civil war. During his tenure, he established a direct relationship with the PLO in Beirut. Because his primary preoccupation was defending the sovereignty and unity of Lebanon, John managed to earn the respect of all Lebanese warring factions. He sought to discourage the relationship between the Maronites and Israel. He felt that such relationships weakened the unity of Lebanon. Beirut was a dangerous place in those years, even for an ambassador, and two attempts were made on Dean's life.

1981-1985 - appointment as American ambassador to Thailand, where he assisted the Thai in coping with the flow of refugees escaping Cambodia and Vietnam.

1986-1989 - appointment as ambassador to India, where he supported the development of science and technology.

After John retired, he and Martine made Paris their home. John served on corporate and academic boards. As a representative of the general director of UNESCO he went back to Cambodia several times.

Sources:

John Gunther Dean's oral history, Jimmy Carter Library: https://web.archive.org/web/20090601133900/http://jimmycarterlibrary.org/library/oralhistory/clohproject/dean.phtml

The American Academy of Diplomacy: https://www.academyofdiplomacy.org/member/john-gunther-dean/

March 1974 - April 1975 - John was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia. By the time John arrived in there, much of the countryside was in the hands of the Khmer Rouge. The U.S. supported the Lon Nol government, which by then was losing control of most of the countryside. Contrary to many at the time, John viewed the Khmer Rouge as cruel, barbarian murderers and felt that once they gained control, the Cambodian people would be slaughtered. John made efforts to bring the two sides to a controlled negotiation table. His efforts failed. With John carrying the American flag on his arm, the 200-member team of the American embassy left Phnom Penn just before the Khmer Rouge took over the city. Failing to reach a negotiated solution and having to desert the Cambodians was a difficult and traumatic experience for John.

Right: John Dean carrying the American flag as the members of the American embassy leave Cambodia in 1975.

In May 1944, Maciej Czarniecki (formerly Albert-Marceli Ashkenazy) wrote a letter from Lwów to his sisters in the United States. It included the sentence, “All other men and women are shotten [sic] from the Germans.” In Lwów, Maciej was caring for two young boys, Piotr (b.1941) and Maciej Jr. (b.1942), and their mother, Valeria Folta. The boys were the sons of Maciej's older brother Dolek (Avraham Adolph) Ashkenazy, who had been murdered by the Gestapo in the winter of 1942, before his second son was born.

Maciej's letter told the story. Almost all the members of the large extended Liebermann family who stayed in the Lwów area at the onset of the war had died of sickness, hunger, in hiding, or in the Janowska camp; others were sent to extermination in Bełżec. Those who survived were Maciej and the children, and Erwin Hirschorn, the son of Israel and Rachela's daughter, Sara Beile. He had left Lwów before the Germans arrived. Maciej, one of Israel Liebermann's older grandchildren, was forty-eight when the war broke out.

Like a few other members of the family, Maciej had served in the Austro-Hungarian army in the First World War. He had been wounded, taken prisoner, and sent to Siberia. After the war, Maciej returned to Poland, completed law studies at the Jagellonian University, and settled in Lwów.

In February 1939, Benno brought his wife Eli and their daughter Hanna (b. 1930) to Palestine. Having deposited them there, he returned to Poland to carry on the business. He was also hoping to convince Filip to leave Poland. Benno left Poland for the last time on August 26, 1939, on the last regularly scheduled civilian flight out of Warsaw.

Other than the land and the house, resources were very scarce. Income from the land and the house had to provide for four families. They established a convalescent home for young Holocaust survivors who arrived in Palestine. At one point, Benno took a clerical position in the Ministry of Interior of the mandate government. This was a hard adjustment for a man who was used to owning his own business and managing other people. In letters written to a close friend, Benno often mentioned his despair. In the years prior to the declaration of Israel's independence, Benno's outlook regarding the prospect of peace between Arabs and Jews in Palestine became more and more pessimistic.

The Children and Grandchildren of Israel Liebermann and Chana Waldinger

© Valerie Schatzker 2016

This page is hosted at no cost to the public by JewishGen, Inc., a non-profit corporation. If you feel there is a benefit to you in accessing this site, your JewishGenerosity is appreciated. http://www.jewishgen.org/JewishGen-erosity.

Rozalia Liebermann (b. 1877)

The fate of Israel Liebermann's ten children and grandchildren

Israel's eldest children Mina and Filip enjoyed wealth, but the rest led a relatively modest lifestyle. Much of Israel's wealth had disappeared by the time they had grown up. Still, the younger siblings were well educated; the men acquired professions, some of them with the help and the support of Mina's and Filip's family members. Whatever wealth was left was dedicated to educating the young.

Of his children with Rachel Weingarten, Meilech (Michal) and Joachim, the youngest, were physicians, and Marcus (Marek) was a lawyer. Hise daughters married professionals. Rozalia, Chana Waldiger's daughter married a physician, as did Tula, Rachel Weingarten's daughter; Of Rachel's other daughters, Antonia married a pharmacist and both Sara-Beile and Ides married clerks who worked for the Austro-Hungarian railway system.

Family members, many of whom lived in the old Jewish quarter in the center of Lwów, resided in close proximity to each other. From the correspondence of the survivors and from a detailed memoir left by one of them, it seems they maintained strong, active ties. These ties began to disintegrate when the war broke out in the fall of 1939; when the Germans entered Lwów in July 1940, all hell broke loose.

Of Israel's descendants who were in Lwów at the time the war broke out, three survived:

Survivors

Leon Aszkenazi (later Leon Bouvier), 1926-2006: son of Adolph Dolek Ashkenazi, Israel's great-grandson.

Erwin Hirschorn, 1918-1985: son of Sarah-Beila Liebermann, Israel's grandson.

Albert–Marcel Ashkenazi, 1891-1949. Changed his name to Maciej Czarneicki. Israel's grandson, the son of Mina Ashkenazi.

Those who perished:

Ida (Judes) Marbach (1875-1941), Israel's and Chana's daughter, a widow, most likely perished in the first “action” in Stanisławów in October 1941.

Maurycy (1873-1941), Israel's and Chana's son, taken from his home in Kołomyja in late 1941.

Sarah-Beila Hirschhhorn (1882-1941), Israel's and Rachel's daughter, beaten to death by a Ukrainian mob shortly after the Germans entered Lwów.

Meilech (Michał) Liebermann (1880-1942), his wife Berta, and their two children, Jurek 16, Rena 12, the son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren of Israel and Rachel. Michał had a nervous breakdown, left his hiding place, and was shot, Jurek died in Janowska concentration camp. Rena was hidden for a while, then had to leave and disappeared.

Marcus (Marek) and his sister Tonia Seckler (1876-1942), children of Israel and Rachel, perished in Lwów.

Tula (Chaja-Tille) Pachtman (1880-1942), Israel's and Rachel's daughter, and her son Marcel (1913-1942) were deported from Vienna. Marcel died in October 1940 in a concentration camp.

Joachim (Karol) Liebermann (1885-1943), Israel and Rachel's son, his wife Chaja-Klara (1892-1942), and daughter Stella 12. Joachim practiced medicine in the ghetto in Drohobych until he perished.

Abraham (Dolek) Ashkenazy (1886-194), Israel's grandson. He was caught in the streets of Lwów without an armband and disappeared.

Anna Blanca Landau (1904-1944), Israel and Chana Waldinger's granddaughter, Anna Landau was deported from the Drohobycz ghetto to Auschwitz. According to a relative's testimony, Anna Blanca survived Auschwitz; weakened and sickly, she died shortly after she was freed.

The above photographs and information were submitted by Rachel Liebermann Evnine, a descendant of Israel Liebermann.

The Children of Israel Liebermann and Rachel Weingarten

Sara Beile Liebermann (b. 1877)

The fourth of Israel and Rachel's five children Sara-Beile married Osias Hirschhorn (b. 1875). Like her sister Ides' husband, Odias was a clerk who worked for the Austro-Hungarian railway system. He died when their son Erwin was eleven years old.

During his adolescent years, Erwin's older cousin, Maciej Ashkenazi, was his mentor and a close friend.

A few weeks after the war broke out, Erwin made an attempt to leave Lwów by heading east on foot. After a few days, he turned around and returned to Lwów.

In early 1941, Erwin joined the Soviet army. He ended up spending the autumn and winter of 1942-43 fighting in the battle of Stalingrad; he continued to fight with the Red Army after that epic battle. While making his way back to Poland, he stopped in Moscow, where he learned that Maciej, his surviving cousin, was looking for him. Erwin searched for Maciej in Silesia but Maciej kept moving from one place to another. Finally, the two were united. Together with Maciej were his brother's two children, their mother Valeria Folta and her sister Viktoria. The two cousins settled in Poland with the two sisters. At that time, Erwin Hirschorn changed his name to Roman Dorosz. Growing up, Roman's son and daughter had no idea of the family's connection to the Liebermann family or to their Jewish roots. They were aware, however, that they had barely any relatives. At the same time that Erwin kept his old identity from his children, he maintained some connection with family members in other parts of Europe and with a few in other parts of the world. There was no communication with his relatives in Israel.

Erwin Hirschhorn (Roman Dorosz) 1941-1985)

Shortly before he died in the mid 1980s, Erwin began writing a memoir telling the history of the Liebermann family and detailing much of what he he had able to learn from his cousin Maciej about the fate of the family members who resided in Lwów and had perished during the war.

When Erwin's widow Viktoria died in the early 1990s, Erwin's children found the memoir among other records that were left behind. This is how Erwin's children and later his grandchildren learned about their connection to the Liebermann family and their Jewish paternal lineage. Thanks to this memoir, some of Israel Liebermann's descendants were able to meet and spend time togethe, and renew a sense of connection that had been lost as a result of the war.

Much of the report in this story is base on Erwin's memories.

Currently, Magda Dorosz, Erwin's granddaughter, is the executive director of Hillel Warsaw. In this position, she is dedicated to students who, like her, unexpectedly discovered their Jewish roots and who want to know more about Jewish traditions and be involved with other youngsters with similar experiences.

Léon Bouvier (Léon Aschkenazi) 1926-2005

The Children of Israel Liebermann and Chaje Donnenberg

with help of family ties and contacts, and with the intervention of the French Consulate in Moscow, he obtained papers that allowed him to leave the Soviet zone. He then went to Romania. Upon arriving, he learned of the invasion of France and the signing of an armistice by the new government of Marshal Pétain. Léon decided not to return to France, as proposed by the French consular authorities of Bucharest; instead he joined the fighting units of the Free French army, which was stationed then in the Middle East.

After a long journey that lead him to Istanbul and Haifa, he finally arrived at Ismailia, Egypt, where he joined the 1st Marine Infantry Battalion (1st BIM) of the Free French forces . At the time of his arrival he was not yet seventeen. He was placed under the command of General Pierrre de Chevingé. When he reliazed Leon's true age, which Léon had tried to conceal, the general refused to take Léon to Eritrea, where the division was heading. In the winter of 1940-1941, Léon was sent to the French Lycée in Cairo, where he completed his high school education.

In the spring of 1941, Léon either graduated from high school (according to his official biography), or ran away (according to an interview he gave to a British journalist). Either way, he eventually made it back to Palestine. Léon joined the independent French forces and took part in the Syrian campaign, freeing Syria from Vichy control.

In September 1941, Léon was appointed to the Pacific Battalion. At first, he did secretarial work but soon requested a more active assignment. In December he was appointed as a driver in the 101st division. He was part of the first brigade

that left for Libya under General Pierre Koenig. Private Bouvier drove a truck in the convoys that supplied ammunition to the free French army besieged in Bir Hakeim.

On June 8, 1942, Léon was wounded at Bir Hakeim. Here he tells it in his own words to a British journalist.

“I was driving one of fifteen lorries which had gone to get supplies through the German lines. We were on our way back, fully loaded, and everything had gone fine. The Germans had failed to notice us in the dark and already, the officer who was to guide us through the minefields back into our own lines, had met us, when – possibly because they heard the noise of our engines – Jerry started firing at us. One lorry was hit and set on fire. It was full of seventy-five shells, but it was all right – the fuses weren't on! But if the fuses, which were also in the lorry, had caught fire – it was the end of us all! So I jumped on board and got the cases of fuses out of the lorry. Unfortunately, a bomb came and the fuses – and I – blew up together … my comrades thought I was dead, and in any case they had to get the ammunition in at all costs. They left me. But a British patrol, some distance away, had seen the big explosion, and as it was in German-held territory they came to have a look. They picked me up, and I was in pretty bad shape – the right arm gone altogether and the left one badly damaged. Three Scottish soldiers gave their blood for me. I have 60 percent Scottish blood … and am proud of it!”

Following a long journey via Cairo and Alexandria, Léon was brought to the French military hospital in Beirut, where he was treated and recuperated. Later, General Charles de Gaulle made Léon Compagnon

Léon (Bouvier)after being wounded in 1942

de la Libération for his deeds that day. He was eighteen at the time, the youngest ever to receive such a medal.

On May 1, 1943, Léon entered the officer school of the independent French army in England, whence he left to assume roles in Corsica and Savoy in December 1943.

In April 1944, Léon participated in the campaign of France as an attaché to Colonel de Chevigné; he participated in the liberation of Paris, Metz and Strasbourg before being transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February 1945.

Promoted to lieutenant, in January 1946, he left to study in Montréal before returning to France where he successfully passed the entrance examination at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He began a long diplomatic career that would lead him to represent France in many countries. He served as First Secretary of the Embassy in Stockholm in 1962 and as Economic Councillor in Berlin in 1965.

In 1972, he served as Consul General in Frankfurt-am-Main. He was then appointed Ambassador to Paraguay in 1977, Ambassador to Chile in 1981 and to Denmark in 1985. He was awarded the honor of Ambassador of France in 1987, before retiring the following year. He was a member of the Council of the Order of the Legion of Honor since 1992, and a member of the Council of the Order of the Liberation since 1995.

Léon Bouvier died on July 23, 2005 in Paris. He is buried in the Montrouge Cemetery. He was survived by his French wife Christiane, and four children: Benjamin, Eric, Lorraine and David.

Honours

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor

Companion of the Liberation - Decree of September 9, 1942

Military Medal

War cross 39/45 with palm

Resistance Medal with Rosette

Colonial medal with staples "Libya", "Bir-Hakeim", "Syria"

Medal of the wounded

Volunteer's Cross Volunteer 39/45

Military Cross (GB)

Officer of Cedar (Lebanon)

Grand Cross of the National Order of Paraguay

Grand Cross of the Order "Al Orden Merito" (Chile)

Grand Cross of the Dannebrog Order (Denmark)

Officer of the Order of the White Rose (Finland)

Laura (Lucia), the second daughter of Lazer and Mania, married Joseph Diensfertig, a successful lawyer from Breslau (Wrocław) in Silesia. They had two sons: Wolfgang (1922-1938), and Gunther (John) (b.1926). Joseph worked in banking. In addition, he was a member of several boards of directors of well-known industries and also served in leadership roles in the large secular Jewish community in Breslau.

Laura Ashkenasy-Dienstfertig

Joseph Dienstfertig

Laura Dienstfertig with her son Gunther (John)

Following a brief stay with friends and colleagues in Holland and a few months in England, the family arrived in the U.S. and settled in Kansas City, MO. It was then that John's parents changed their surname from the German Dienstfertig to the more American sounding Dean. Their son Gunther took the first name John.

Hermann (Hersch) Liebermann, the grandchild of Feiwel Libermann and the oldest child of Joseph Leibermann and Hudes Dutzend (b. 1851), became a prominent lawyer and politician both in Galicia, when it was part of Austria and later in the Second Polish Republic. He became active in Polish political activities while still a high school student. He studied in Paris and later at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków. In Paris, he came into contact with social democratic ideas. In Przemysł, where he practised law, he often defended political activists. He became active in the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) of Galicia and Silesia and editor of the paper Głos Przemyski.

From 1907 to 1914 and from 1917 to 1918, Liebermann was a member of parliament in Vienna. During World War I, he joined the Polish Legions of Józef Piłsudski as a private. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant and took part in the Battle of Kostiuchnówka, for which he was awarded the Polish Cross of Valour. During the Oath crisis, when Polish troops refused to swear allegiance to Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, Lieberman served as the lawyer for the legionaires who were charged with treason by the Austrian authorities for flouting orders .

With the establishment of the Polish Republic in 1919, Lieberman was elected a a member of the PPS to the Polish Parliament. Although he had been closely associated with Józef Piłsudski, he moved quickly into the opposition after the coup of May 1926 and was one of the principal figures in the creation of the Centrolew (Center Left) that challenged the new government. When Piłsudski took violent action against the democratic opposition, Liebermann was one of those arrested and mistreated in the military fortress of Brześć (Brest). He was arrested and beaten by the police and then sentenced to two and a half year in prison in the 1931–32 Brest trials. Rather than serving the sentence, he emigrated to France. While abroad he supported the republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and published a critical response to Marcel Déat's pamphlet Why Die for Danzig? which advocated appeasement of Hitler.

After the 1939 Nazi invasion of Poland, during World War II, he joined the Polish government-in-exile of Władysław Sikorski. From 3 September 1941 to 20 October 1941, Lieberman was the minister of justice of this government in London, England.[1] He died in 1942.

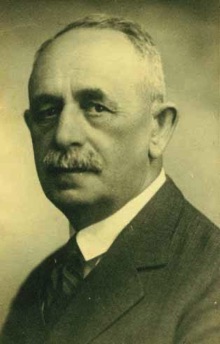

Hermann Liebermann

Descendants of Feiwel Liebermann and Reisel Strauser

Hermann Liebermann (1869-1942)

A contemporary drawing of Hermann Liebermann

In 1941 Lieberman was posthumously awarded Poland's highest decoration, the Order of the White Eagle, by the President of the Government in Exile Władysław Raczkiewicz in recognition of his exceptional services to Poland.

Erwin Hirschhorn (Roman Dorosz)

In May 1947, Klara gave birth to a daughter, Rachel Liebermann

Dolek was in medical school in Italy when the war broke out. He was able to emigrate to the United States. Like his father, he became a physician

During the Nazi invasion, Blanka’s husband David was killed. She and her daughters were hidden by righteous families, however Blanka was later captured and sent to Auschwitz. According to a relative's testimony, Anna Blanca survived Auschwitz but weakened and sickly, she died shortly after she was freed.

See the Lichtgarn Family

Anna Blanka and Dolek Lichtgarn circa 1925

Léon was ten years old, his parents sent him to study in Paris. He entered the Michelet Vanez high school as a resident of the French state.

In the summer of 1939, Léon's mother died. He attended the funeral in Vienna and a then joined his father who was working at that time in Warsaw. When the Germans invaded, he and his father escaped to Lwów, where his grandmother, uncle, and many others from his extended family lived. Lwóow was at that time under Soviet control as a result of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Agreement.

With dwindling means and not able to speak Russian, Léon spent the harsh winter of 1939-40 selling Soviet newspapers in the street. In the spring of 1940,