Photo 5

|

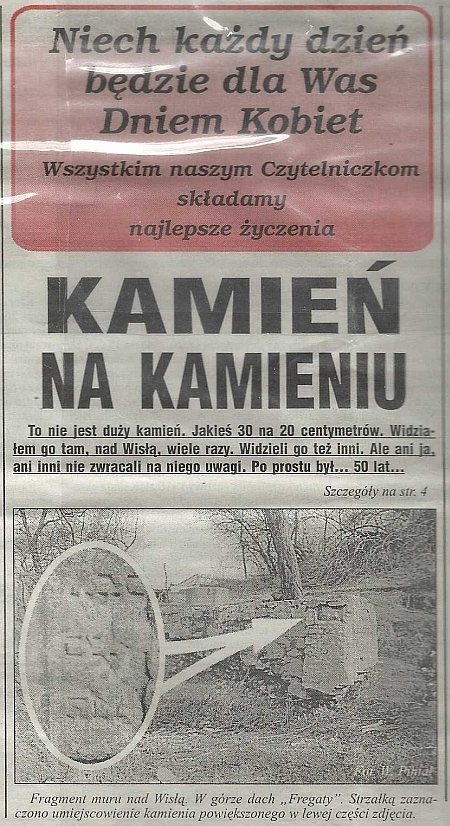

[Beginning with the text below the box in pink, "Kamien na Kamieniu..."] Stone on stone It is not a big stone. Some 30 x 20 cm. I saw there, on the Wisla, many times. Other salsa. But neither I nor the others paid any attention to. That's I was for 50 years. Details on page 4 [Photo, followed by caption} a fragment of the wall on the Wisla. Above it is the roof of "Fregata." The euro points to the location of the stone, which is enlarged in the left side of the photograph. Photograph by W. Pintal. ===The whole story began on the Internet. Marek Duszkiewicz, a man of Tarnobrzeg from the United States of America, posted an appeal from an American of Jewish descent, Gayle Schlissel Riley from California, on Tebegielka (this is a discussion list about Tarnobrzeg). She was asking for any photos from the old Jewish cemetery of Tarnobrzeg. The cemetery existed before the war in the spot where the renovated market Hall is currently located, next to the court buildings. I had no such pictures, but I remembered this one stone... STONE ON STONE On the Wisla, not far from the "Fregata," there is a little fountain. Many residents of the Przywisle settlement know it very well from their numerous walks along the water. Just 10 years ago, interruptions in the water supply were an everyday occurrence for the people of Tarnobrzeg. Carts distributed water. Anyone who didn't want water from their barrels went to this fountain. By it stood a revetment [supporting facing] (see the photo). And in its upper right corner ... this stone. It would have been no different from the others, old and covered with moss, if it weren't for the writing. The letters carved into it clearly showed that this was no ordinary stone. REST IN PEACE When Ms. Riley received the photos, she was unusually excited, and had no doubt that this stone, or rather a fragment of it, was from a Jewish tombstone. She sent a copy to her cousin in Israel, who translated the inscription. There are individual words from three columns of the inscription: "Upright" (in the sense of an upright person), "Kagan" (no doubt, a surname) and "rest." This American lady was shaken by my mailing. I should add that Gayle Riley is a tireless researcher of the history of Tarnobrzeg, especially during the time When Jews predominated among its residents. Her ancestors came from there. She collects archivalia, gathers photographs, old postcards, popuation lists, and the like. You can familiarize yourself with the fruit of her searches on her Internet site about Tarnobrzeg - http://www.shtetlinks.jewishgen.org/Tarnobrzeg/. It is an impressive collection. There are, for instance, maps of Tarnobrzeg from the second half of the 19th century! So it is no surprise that Gayle Riley begged to know where this stone was from that was in the wall and whether it could be returned to the cemetery. I did not know the answers to these questions. Fortunately, there are still people of Tarnobrzeg from the old days. One of them is Ryszard Durzynski, born there before the war. He remembers this old cemetery very well. His parents' house stood next to it, on the corner of what are now Pilsudski and Wyszynski streets. CAJWY AND BONES "This was a closed cemetery," R. Durzynski remembers. "No one had been buried there since the early 20th century. It was surrounded by a wall and tall trees grew all over. Behind it was the synagogue, the present library. During the occupation, the Germans ordered the liquidation of the cemetery. An elevation that had been there was leveled, the wall was taken down, the trees were cut down, and the _cajwi_ -- which is what we called the matzevahs from the graves -- were shattered and thrown down everywhere. There were also a great many bones there. Jews who returned to the city for a time city after their first expulsion asked the Germans -- no doubt with a bribe -- for permission to gather the bones and take them to the new cemetery on Sienkiewicz street. Here's how it was with this wall. After the war, up until the mid-50s, the Polish army organized training camps every year on the Wisla. There were tents and a field kitchen. They drew the water for this kitchen from the fountain. But it was always muddy there, so for convenience, some time in 1949, they erected a revetment and put the area around the fountain in order. They used whatever was nearby to build it, especially stones in the field. Undoubtedly at some point they found a piece of the _cajwi_ and without thinking put it in wall. If they had wanted to conceal this, they would simply have turned it around to the other side. The facts support Mr. Durzynski's tale. After the war, stones from Jewish tombstones were used to harden roads and plazas. For example, in Opatow, matzevahs were placed on the banks of the river Opatowka where it flows through the town. Not until the 90s were they recovered and placed in reconstructed cemeteries. I sought the answer to the American's For second question in the city office. For both president Jan Dziubinski and his spokesman, Jozef Michalik, a matzevah in the revetment was a complete surprise. They suggested that the conservator of relics deal with the matter. Further decisions were issued by the vice president, Tadeusz Zych, who soon stated: "putting anyone's tombstone in a collapsing wall is a fact that should fill every decent person with shame. As quickly as possible, the city staff under me will take the stone from the wall. Its subsequent fate may be twofold. Either we can simply place it in the cemetery on Sienkiewicz street, or it can become a fragment of a tablet commemorating the old cemetery that we intend to put in the wall of the renovated market Hall ... [illegible]. We will be glad to accept the suggestions of Jewish communities in this matter." One thing remains to be established: whether the stone comes from the old cemetery or the new? Only a few matzevahs are to be found at the new one. The rest, as the older residents say, are under the pavement of Sandomierski Street and the road to Ocice. Waclaw Pintal [Separate box] In 1939, there were 3,800 Jews living in Tarnobrzeg. After the war, none of them returned. Up until the 90s, the only resident of Tarnobrzeg of Jewish descent was the modest and popular Dr. OLGA LILIEN. But she did not live in Tarnobrzeg before the war. She survived the occupation thanks to the nuns of Mokrzyszow, who concealed her at their farm. After her death, a memorial tablet was consecrated to her, which is located in the new hospital building. Translation by Fred Hoffman |