|

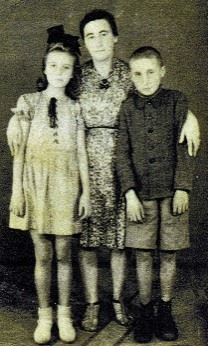

Aron Nusbaum

Photograph

courtesy of Yad Vashem

|

The following testament was

written by Jewish prisoners in the Chelmo death

camp and found there after the war.

2 April 1943

This note is written by people who will live

for only a few more hours. The person

who will read this note will hardly be able to

believe that this is true. Still, this

is the tragic truth, (in this) place your

brothers and sisters stayed, and they, too,

died the same death! The name of this

locality is Kolo. At a distance of 12 km

from this town [Chelmno] there is a

'slaughterhouse' for human beings. We

have here as craftsmen there [illegible word],

I can give you the their names.

Pinkus Grun of Wloclawek

Jonas Lew of Brzeziny

Szama Ika of Brzeziny

Zemach Szumiraj of Wloclawek

Jesyp Majer of Kalisz

Wachtel Symcha of Leczyca

Wachtel Srulek of Lexcyca

Beniek Jastrzebski of Leczyca

Nusbaum

Aron of Skepe

Ojser Strasburg of Lutomiersk

Mosiek Plocker of Kutno

Felek Plocker of Kutno

Josef Herszkowicvz Plocker of Kutno

Chaskel Zerach of Leczyca

Wolf Szlamowicfz of Kalisz

Gecel of Turek

These are, then, the persons' names which I

give here. these are only a few people

from among the hundreds of thousands who died

here!

Source: Kleinman, Yehudit and Dafni,

Reuven (Eds.) Final Letters--From the

Yad Vashem Archive, London 1991, Weidenfeld

and Nicolson, pp 119-122

|

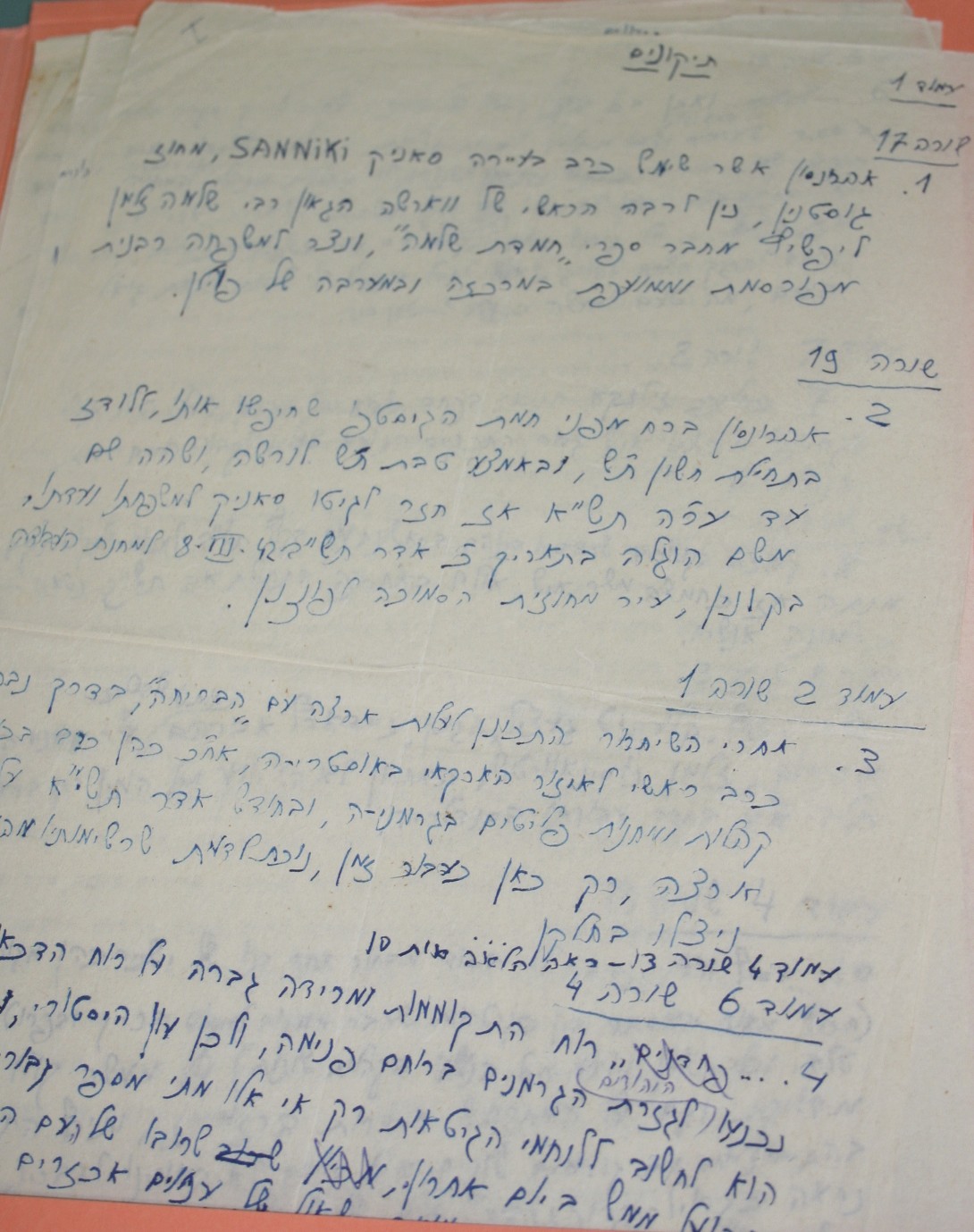

Szymon

Pozmanter

|

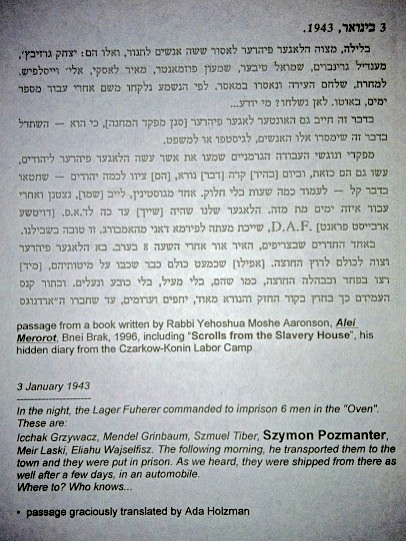

A page from the hidden diary of

Rabbi Yehoshua Moshe Aaronson,

The Scroll of the House of Bondage in Konin

from the collection at Beit Lohamei Haghetaot,

Ghetto Fighters' House Museum

Photo by Roberta Fleishman

The following

is a translation of the Rabbi's Diary by Ada

Holtzman, who maintains a Holocaust Research

Website:

http://www.zchor.org/ALEI.HTM

Her message about the Diary follows:

The document is called : "Scrolls of the

Slavery House", written in hiding by Rabbi

Yehoshua Moshe Aharonson while the events

took place in Czarkow concentration camp

near Konin, Poland.

The diary was found after the war and

published in a book "Alei Merorot", by the

son, R' Y. Aharonson, Bnei Brak, 1996.

---------------------

In

the night, the Lager Fuherer commanded to

imprison 6 men in the "Oven". These are:

Icchak

Grzywacz, Mendel Grinbaum, Szmuel Tiber, Szymon

Pozmanter, Meir Laski, Eliahu

Wajselfisz. The following morning, he

transported them to the town and they were

put in prison. As we heard, they were

shipped from there as well after a few days,

in an automobile.

Where

to? Who knows...

CZARKOW Labor Camp

After the Jews

of Konin had been annihilated, a work camp

was established on the site. In March 1942

more than 800 Jews from the area of Gostynin

and Gabin (Gombin) were brought there and

employed in harsh forced labour. Many of

them died from exhaustion and disease.

Forty-five Jews from the camp prison were

buried in the Christian cemetery in Konin,

but on July 17, 1942, their bodies were

removed on the orders of the mayor, and

interred in a nearby plot among other Jews.

At the beginning of 1943 many of the

inhabitants of the camp were transported to

their deaths in Chelmno and other

concentration camps. This was the signal for

some Jews to band together and carry out

acts of sabotage and arson in the work camp.

In August 1943 this underground group

learned that the Germans were about to kill

all the internees, and it set on fire a

number of huts. Most of these saboteurs met

their deaths in the action, but some

survived. Following an investigation into

the circumstances of the insurrection, the

camp was closed and the captives moved to

assembly points, and eventually to

Auschwitz.

Among the prisoners in Konin and the group

of rebels was Rabbi Yehoshua Moshe Aaronson.

While in the camp he wrote a diary entitled

“Megillat Beit Haavadim”. This diary and

other testamentary documents he hid in two

bottles, which he gave into the keeping of a

Polish carpenter. Only some of these papers

survived, but they bore witness to the life

and fate of the internees in the camp at

Konin.

This is a translation from: Konin

Chapter; Pinkas Hakehillot:

Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland,

Volume I, pages 235-238, published by Yad

Vashem, Jerusalem

|

|

|

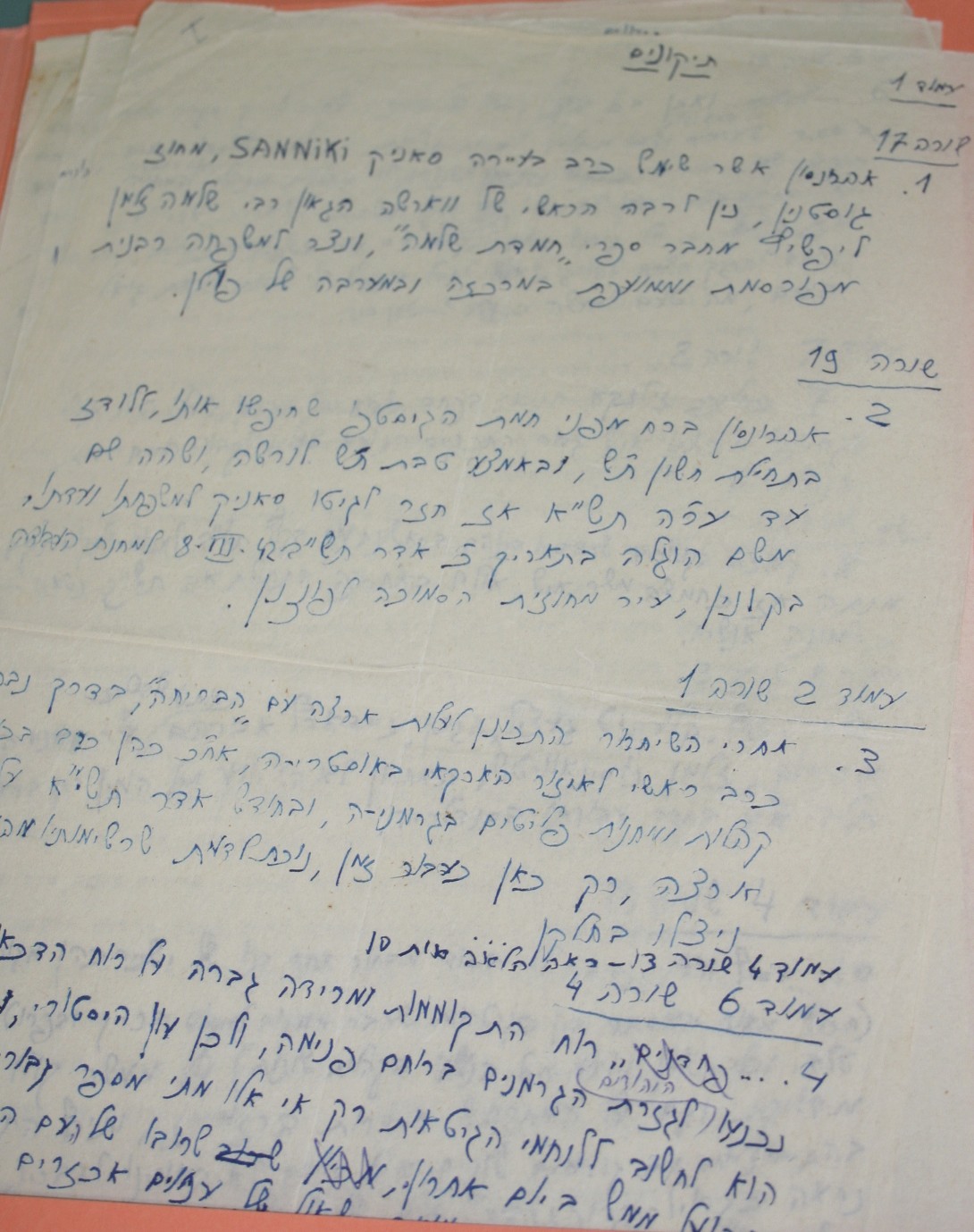

Szlama

Pozmanter

Photograph

courtesy of Pozmanter Family Album

Szlama

Pozmanter

Photograph

courtesy of Pozmanter Family Album

|

Szlama Pozmanter

was born in Skepe, Poland on March 1, 1903 to

Chaim Pizmanter and Hendla Gruza. He

married Rywka Zamoskiewicz and they had three

children: Szymon, Fela, and Sarah.

Szlama was a successful businessman and in 1939

paid the fifth largest (175 zloty)“contributions

for the community”. Szlama sold ‘fine

china’ to merchants for resale.

Prior to the start of the war Szlama had been

thinking of moving to a larger city some 40

miles west of Skepe. Rywka had been

pushing to immigrate to Israel, but Szlama saw a

“hard and difficult life there and convinced her

to stay in Poland where they could expect a good

life with better schools, a better house, and

even a maid.” (interview 7/25/2011, Toronto).

With the start of the war on September 1, 1939,

the German invasion took little time getting to

Skepe. By the end of December, 1939, the

Jews of Skepe were ordered to move out of

town. Szlama and Rwyka took their three

children and were joined by Rywka’s older

sister, Brania and her family of husband David

Flusberg and daughter Sarah. Brania,

David, and Sarah had been expelled from Bad

Oldesloe, Germany in 1938, where David was a

shochet and moved to Skepe.

Szlama’s family and his sister-in-law’s family

traveled to Warsaw. The youngest sister of

Rywka and Brania – Chava, also of Skepe – took

her family to Gostynin to live with her

husband’s family. While in Warsaw Szlama

would make soap and sell it in one of the ghetto

markets. His daughter Fela would keep

watch for German soldiers who would periodically

make sweeps of the street.

In October, 1941, the Pozmanter and Flusberg

families realized it was time to leave the

Warsaw ghetto. They traveled with

ingenuity and chutzpah to make it to Gostynin

and be with Chava and her family.

On December 1, 1941, Szlama was arrested in

Gostynin and transported to a series of labor

camps. Records indicate Szlama was at a

slave labor camp for Jews in Gostyn (called

Gostingen by Germans) and in Kostrzyn, both of

which are in the Poznan province.

“Salomon Pozmanter….was sent to KL Auschwitz in

August 28, 1943 from slave labour camp for Jews

in Kostrzyn (Poznan province). He received

his prisoner’s number 142161. In January

22, 1945 he was transferred to KL Buchenwald

where he received prisoners number 119312.

There isn’t information about his further

fate.” (Auschwitz Museum Archives, March

16, 2011; Ref-I-Arch-i/7834/10)

Family members report that surviving prisoners

remember that Szlama Pozmanter gave up hope that

he would ever see his family alive and perished

a short time before liberation.

|

|

Abram

Cudkiewicz was a merchant of fabrics according

to the 1929 Polish Business Directory. He

was the father of at least 8 children.

Most of his children emigrated from Poland

beginning in 1911 when Mordcha-Leib left for New

York City. Over the next 26 years 4 more

sons and two daughters would leave.

In 1939 Abram paid 50 zlotys as a contribution

for the community and his youngest son, Tzadek,

was studying to be a Rabbi. Neither Abram

nor Tzadek survived the Holocaust.

|

|

Tzadek Cudkiewicz

|

Photographs courtesy of Berg

Family Album

|

Ytzkhak

Avraham Cudkiewicz |

Rubinsztejn

Family

Szamuel

Chaim

Photographs

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum,

courtesy

of Dora

Rubinsztejn Weiner

Abraham Baer

Photograph courtesy of Yad Vashem

|

The Rubinsztejn

family about 1924. Chaya Ester and Hersh Yitzhak

hold their sons, Abraham Baer, left, and Szamuel

Chaim in Skepe, Poland, early 1920’s.

Dworja Raca Rubinsztejn, not pictured, (now Dora

Weiner) is the daughter of Hersh and Chaya

(Grynberg) Rubinsztejn. She was born February

17, 1927 in Plock, Poland, where her father was

a Jewish ritual slaughterer. Dworja had two

older brothers, Szamuel and Armand, both of whom

were born in Skepe, Poland in the early 1920's.

The family lived in Plock until the spring of

1929, when Chaya took Dworja and Armand to Paris

to live with her brother's family.

To appease his father, Hersh stayed behind in

Plock with Szamuel. After the German occupation

of northern France in 1940, Chaya and the

children moved south to Grenade sur Adour.

Subsequently, eighteen-year-old Armand was sent

to the Septfondes labor camp. In 1943 he was

transferred to Gurs and then deported to the

east by way of Drancy.

In September 1942 Dworja was sent to live in

Lacaune les Bains, where she was required to

check in weekly with the police. Then, in the

spring of 1944 Dworja went into hiding in L'Isle

Jourdain with false papers provided by the

Maquis resistance. She remained there until the

liberation. Dworja then returned to Paris, where

she lived until her immigration to the United

States in May 1949. She sailed from Cherbourg to

New York on the R.M.S. Queen Elizabeth. Dworja's

mother also survived the war hiding in France,

but her

father, Hersh, and two brothers perished

in Poland.

Explanation from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial

Museum courtesy of Dora Weiner.

Abraham Baer Rubinstein, pictured on

left, was born in Skepe on November 29,

1923. After leaving Poland in 1929 he

moved with his mother Chaya and sister Dworja to

Paris. In 1940 the family moved to Grenade

sur Adour, France after the German

occupation. After spending time in a labor

camp Abraham was deported from Drancy, France in

March, 1943. He perished in Auschwitz.

Photo courtesy of Yad Vashem.

|

The Rabbi's

wife (Zontag)

Photograph

courtesy of Yad Vashem

|

The wife of Skępe Rabbi Jachiel Halewi

Zontag. Rabbi Zontag served in Skępe for

nearly 10 years and died in 1932 or 33.

According to a Skępe survivor Rabbi Zontag’s

widow married another Rabbi.

|

Braina

Zamoskiewicz Flusberg

Photograph

courtesy of Shavit Family Album

|

Braina Zamoskiewicz (b. Skępe) and David

Flusberg (b. Dobrzyn: mod. Golub-Dobrzyn) were

married in the early 1900's. They had two

daughters: Rosa who was born in 1912 in

Dobrzyn and emigrated to Israel before the war;

and Sarah who was born in Blumendorf, Germany in

1920 and remained with her parents in Bad

Oldesloe until their expulsion in 1938.

David was a shochet, and according to a 1938

German Census, he and Brania shared their

address with a mother and son in Bad Oldesloe.

According to American relatives an effort was

being made to bring the three Zamoskiewicz

sisters and their families to the United States

via Hamburg. These efforts failed and

Braina, David, and Sarah left for Poland and

stayed with relatives. Here is one

account.

"Yehoshua Flusberg is the son of Elya-Mordechai

Flusberg, who was David Flusberg’s brother and

the brother-in-law of Braina. He was born in

September 1926. I asked him what he remembered

about Sarah Flusberg (David and Braina’s

daughter). Here is what he told me:

'When David, Braina and their daughter Sarah

were expelled from Germany around 1938, they

moved to Dobrzyn, where they moved in with

Yehoshua’s family, staying in their house.

Yehoshua was 12 years old, and he recalls that

Sarah, who was about 18 at the time, brought

attention to herself because of her very proper

German manners (Yehoshua jokingly referred to

her as a “Yeke”, which is the Yiddish expression

for someone who is very German-like—not

surprising for someone who had been raised in

Germany). He recalls their first Friday-night

dinner together. Yehoshua’s mother had served

gefilte fish, a typical Friday-night delicacy,

which Sarah apparently loathed. However, Sarah

was too well-mannered to decline the portion she

had been served; instead, she pretended to eat

it, discretely hiding it, piece by piece, in

various places under her dress.

Yehoshua recalls that his older brother (also

named David Flusberg) was about Sarah’s age and

took a liking to her.

Some time in 1939—Yehoshua thinks it was only a

few weeks before the German invasion—David,

Braina and Sarah moved to Skępe to join Braina’s

family.

When the German invasion began, Yehoshua and

family (his parents and brother) fled from

Dobrzyn to Skępe in the middle of the night. He

recalls walking all night along a shortcut

through the forest that his father was familiar

with. Because of their fear of being molested by

anti-Semites, his father had tied a handkerchief

around his face to hide his long beard. They did

pass some retreating Polish soldiers, but no one

bothered them. They arrived in Skępe, where they

stayed with David and Braina for about a week.

It was Yehoshua’s 13th birthday, and he recalls

his first “aliya”—his bar mitzvah—took place in

the Skępe synagogue. As he left the synagogue he

observed the very first German soldiers arriving

in Skępe on motorcycles.

Story

recounted by Allen Flusberg

|

|

|

Chava

Zamoskiewicz Strikowsky

Photograph

courtesy of Shavit Family Album

Moshe Strikowsky

Photograph

courtesy of Shavit Family Album

|

Chava Strikowsky was the youngest of the eleven

Zamoskiewicz siblings. She married Moshe

Strikowsky who was a tailor and owned a small

clothing store in the Skepe town square across

from her sister Rivka’s grocery store.

Chava had three children, Avraham (b. 1935),

Felusha (b. 1937), and Yekhiel (b. 1938).

In early September, 1939, the Germans arrived in

Skepe on their drive to Warsaw. One night

not long after the start of the war many of the

Jewish men of Skepe had been taken from their

homes. Chava’s husband was one of the men

and he would never be seen again. By the end of

the year the remaining Jews were ordered out of

Skepe. While Rywka and her family traveled

to Warsaw Chava and her three children were

moved to the (Strzegowo) Ghetto. Avraham

writes of the experience:

“The gendarmes walked around with clubs in their

hands and rifles on their shoulders,

yelling: ‘Schnell! Schnell!’ There were

also many Poles helping the Germans to yell and

push the people onto the trucks…There were no

benches and we stood tightly packed. The

Germans closed the tarp, leaving no air, (only)

the darkness. Little children cried, the

elderly coughed, and the mothers calmed….I don’t

remember how long we spent in the (Strzegowo)

Ghetto, a year, maybe more.

One morning two Capos burst into the building

and yelled: ‘In one hour all of you are to be

outside with your clothes. You are leaving the

ghetto!’ Much panic ensued. Rumors were

spreading that there were concentration camps,

from which no one leaves alive….(When the) truck

stopped and the tarp opened we had arrived at

the Gostynin Ghetto” where Moshe’s younger

brother, Ytzkhak, was a rabbi.

It was to Gostynin that Chava’s sisters (Rivka

and Braina and their families) escaped

after leaving the Warsaw Ghetto in late 1941 and

met up with Chava. Not long after their

reunion the dissolution of the Gostynin ghetto

began in earnest. Periodic roundups of men

were made and they were sent to forced labor

camps in places such as Konin and Posen.

The final liquidation of the ghetto took place

in early 1942 with many taken to Chelmno.

Before that date Rivka arranged for a Polish

farmer to take her and her three children out of

Gostynin one night and Chava and her three

children not long after. After the

placement of Felusha by Chava with a childless

Polish couple she was arrested along with

Yekhiel. Both were murdered. Felusha

and Avraham survived the war and settled in

Israel.

With conditions in the ghetto deteriorating

Rywka and Chava escaped from Gostynin in search

of a place to hide. Not long after their

departure from Gostynin Chava and Yekhiel were

captured and murdered. Felusha and Avraham

both survived the war and eventually made their

homes in Israel.

|

Jews Move

Along a Crowded Street in the Warsaw Ghetto

Photo

Courtesy of the United States Holocaust

Memorial Museum

Photo taken by a German soldier in 1941

and

given to Simon Adelman in 1954

|

The Szaja Gutman

family is emblematic of the Jewish twin tragedy

in the 20th century: immigration and the

Holocaust. The experience of the Gutmans

in Skępe mirrored those of most Jewish families

in Eastern Europe. The Gutmans were not

the exception.

Szaja Gutman was a butcher in the town of Skępe,

Poland as indicated in the 1939 contribution for

the community of 50 zlotys. Szaja already

had witnessed the loss of five sons to Montreal,

Canada with their emigration from Skępe

beginning in 1920. A look at ship manifest

records provides a skeletal look at this part of

the family history.

• On November 8, 1920 Szaja's son, Isek (b.

1895), a tailor, arrived in Quebec aboard the SS

Scandanavian. With $25 in his pocket he

was going to his new life in Canada with cousin,

Efroim Dvalickis, at 65 Duke St.

• April, 2, 1927 on board the SS Estonia two

more Gutman brothers, Szlama Dawid (b. 1905) and

Ide Lajb (b. 1906), tailors, arrived in Halifax,

Nova Scotia from Danzig, Poland on their way to

their brother, Isaac Gutman, 1298 Clarke St.,

Montreal.

• Finally, on May 25, 1929, brothers Szmuel

Jankel (b. 1897) and Pinchas (b. 1911) aboard

the SS Estonia from Danzig, Poland, arrived in

Halifax. Listed as 'laborers' both were going to

brother Szlama who lived at 27 Duluth Ave.,

Montreal. A cousin of the Gutman brothers

- Zalmon Burtkie, a nephew of Szaja Gutman - was

also on the same ship. His passage was

paid by William Smye, a farmer in East Flamboro,

Ontario.

Before the outbreak of the war in 1939 Szaja

Gutman had decided to leave for Canada.

After selling his business in Skępe, Szaja

booked passage for himself, his wife and two

children for Montreal to be with the rest of his

family. He left for Gydnia (Gdansk)

several weeks before the war started, but no

ships were leaving the port. And then at

the start of the war on September 1, 1939 the

port was closed and the remaining Gutmans in

Poland were trapped.

The rest of the story is told by his grand

niece, Faye Pozmanter.

"In December,

1939, all the Jews of Skępe were ordered to

leave their homes and move to Warsaw.

The Pozmanters ran into Szaja and his family

in Warsaw, They were destitute and

approached Faye's father on a number of

occasions for help. Since Szlama

Pozmanter had resources hidden when he left

Skępe he was able to help Szaja and his family

out. However, the Gutmans had no where

to sleep in Warsaw and lived wherever they

found space." When asked about

their fate Faye believed "(the Gutmans)

never made it out of Warsaw. With no

resources they probably did not survive the

early years of the Warsaw ghetto when so many

died of starvation or disease."

|

|