Other Names: Skepe, Skempe (Russian,

German) Schemmensee (German, 1942-45)

Location: 52º52 N 19º21'

E

131 km WNW

of Warszawa

26

miles NNW of Płock

Nearby

cities: Lipno, Sierpc

Jewish Life in Skȩpe

From the Berg Family collection

|

Jewish Families |

Rabbi's

Response to German Invasion |

The Jewish Cemetery |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jewish Families of Skȩpe, 1939 As remembered by Rywka Pozmanter

|

List

of Skȩpe's

Inhabitants in 1939 who Paid the Contribution for the

Community

| Surname and Name |

Occupation |

Amount (zloty) |

| Adler

Anszel |

Baker |

180 |

| Adler Chaim |

Merchant |

40 |

| Adler

Josek |

Merchant |

600 |

| Brodacz

Josef |

75 |

|

| Bruszczyński

David |

Butcher |

10 |

| Bursztyn

Abram |

Merchant |

130 |

| Bursztyn

Izrael |

Merchant |

225 |

| Burtke Hana Rywka | 75 |

|

| Burtke Pinkus | Butcher |

10 |

| Cudkiewicz

Abram |

Merchant |

50 |

| Fagot Icek | Merchant |

10 |

| Fagot

Machał |

10 |

|

| Fogel

Lejzor |

Merchant |

40 |

| Goldberg

Binem |

15 |

|

| Goldman

Salomon |

Hairdresser |

10 |

| Goldman

Szaja |

Butcher |

15 |

| Gruza

Aron |

10 |

|

| Gutman

Szaja |

Butcher |

50 |

| Hartbrot

Dawid |

Merchant |

90 |

| Jakubowicz

Szoel |

Merchant |

30 |

| Kohn

Berek |

40 |

|

| Kohn

Josek |

10 |

|

| Kohn

Nuchim |

Clerk |

15 |

| Kurczak

Josek Mechel |

10 |

|

| Nusbaum

Aron |

Merchant |

60 |

| Ogrodowicz

Chiel |

Merchant |

20 |

| Pieta

Aron |

Worker |

10 |

| Pieta

Lejzor |

Merchant |

40 |

| Pisarz

Jakub Baruch |

Merchant |

20 |

| Podrygał

Chiel Majer |

Baker |

10 |

| Podrygał

Szymcha Hercel |

10 |

|

| Pozmanter

Chaim |

Merchant |

20 |

| Pozmanter

Szlama |

Merchant |

175 |

| Rogensztein

Izrael |

Merchant |

15 |

| Rozenwaks

Anszel |

Merchant |

100 |

| Ruda

Gusen |

Leather

Stitcher |

30 |

| Rywanowicz

Jakub |

Merchant |

60 |

| Sarna

Aron |

10 |

|

| Strykowski

Fiszel |

Tailor |

10 |

| Strykowski

Moszek |

Tailor |

60 |

| Szapiro Szulik | Merchant |

60 |

| Szelka

Icek |

Merchant |

10 |

| Szperling Nachman | Merchant |

10 |

| Winczarski

Szmerel |

Merchant |

10 |

| Winkielman

Rywen |

Merchant |

230 |

| Zeszotko

Chaim |

10 |

|

| Żelek

Aron Fałek |

10 |

|

| Żychliński

Abram |

60 |

Source: APB, UWPT, file no.

4492

Virtual Shtetl

The Jewish Cemetery of Skępe

Virtual Shtetl

|

|

Master and apprentices and other small craftsman

before 1939. This photo now hangs in a meeting

room in City Hall. It was rescued from a local

attic by Zyta Wegner. There are three Jewish

businesses listed: #3 Adler, Gitla--

baker, #26 Gutman--butcher and #72 Podrygal, Chiel--- baker Photo by Roberta Fleishman |

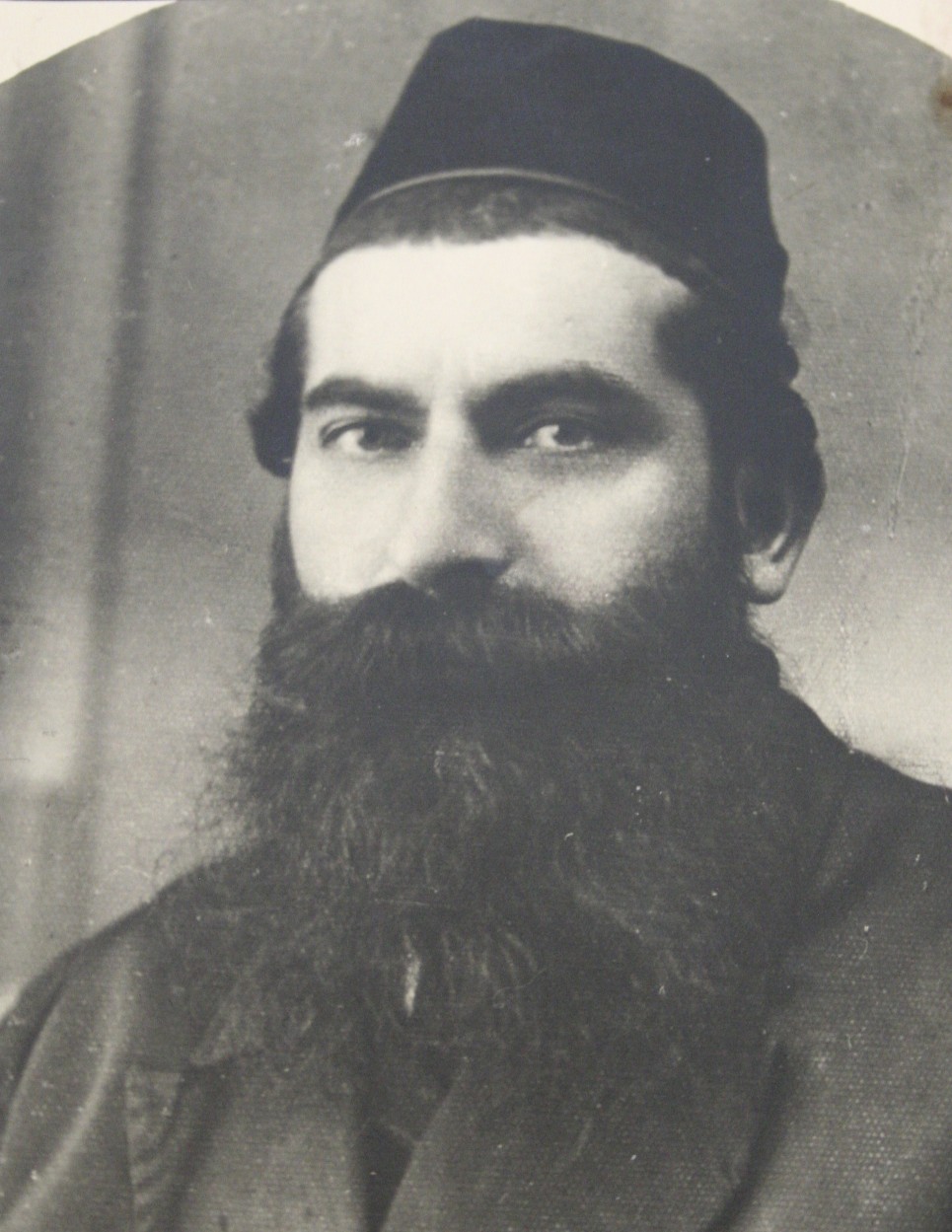

Rabbi Gelernter of Skępe: Religious

Response to German Invasion of 1939

Part of a sixty-four

page Yiddish document in the Ringelblum archives, a

…..

contemporaneous eye witness report….. copied by a single writer, describes the early September 1939 flight of Jews from Skempa (Skepe) Poland from advancing German troops under the guidance of Rabbi Yosef Gelernter (later a member of Warsaw’s Central Refugee Committee). He told his congregants that their flight pointed to Israel’s mission for the sake of monotheism and morality, even amidst suffering (Citing R. Akiva, Berakhot 61b), in the face of eternal hatred (“Sinat olam le’am olam.” Source?). Thus it was with the Jews of the Crusades and the Inquisition. The response had to be the prayer: Shema Yisrael: Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One (“dos tragish Lebn fun unsere Eltern di Kadoshim fun yener Tsayt, ot in azelkhe bitere Shmertsen hobn unzere Eltern oysgehoykht zayre haylike Neshamot mit di letste verter oyf zayner Lipn: Shema Yisrael Hashem Elokeinu Hashem ehad”). Gelernter assured his congregants that God would not cast them away or break their covenant and would even return them to their border (Leviticus 26:44; Jeremiah 31:16). His group reached

the General Government border town of

Dobrzyn-Wista (sic Dobrzyn nad Wisla) on 8

September, Erev Shabbat, not knowing whether to

continue. Invoking the precedent of Joshua’s plea

for Sabbath’s onset to wait until he could

conclude his battle victoriously (Citing

Pirkei Derabi Eliezer ch. 52 to Joshua 10:12), Gelernter asked them to stop for the Sabbath— making a miracle possible. They stayed in place and on Selihot (10 September, Sunday AM) they prayed, saying over and over again with special emphasis: The soul is Yours [God]. The body is Your work. Have mercy on Your people (Amalekhah) [i.e., in history], O have mercy on Your people. (‘Lekhah yom….’ Selihot Lekhal Yom). Throughout this episode, the God of prayer remained the God of metahistory. …….Reports about the Yamim Noraim, which coincided with or immediately followed upon the invasions, indicate that the relationship remained intact, and consciously so. The Skempa Jews praying on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in Dobrzyn-Wista, according to the contemporary account, pleaded (apparently during Tashlikh) “Out of the depths I cry to Thee, O Lord! Lord, hear my voice! Let Thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication” (Psalms 130:2), with such fervor that the report said the plea ascended in ecstasy through the gates of Rahamim up to the throne of glory—even as those standing watch urged them to lower their voices. On the second day of Rosh Hashanah Gelernter recognized that in fact, all mankind was passing before God like a flock of sheep to be judged for slaughter—evoking in his mind the rabbinic interpretation of Leviticus 27:32, where each tenth lamb was sacrificed, and sanctified (“Vekhal ma’aser bakai vatson, kal asher ya’avor tahat hashevet ha’asiri yehiyeh kadosh La’adonai”): Lambs gathered at the door of their shed to be close to their mothers, who waiting desperately at the other side to find out which of their children would be marked red—for sacrifice. (Bekhorot 58b. See Rambam, Hilkhot Bekhorot 7:11). On Yom Kippur (23 September), back in Skempa, fearing that his congregants would be taken to forced labor like the Jews of Lipno and their rabbi Shmuel Halevi Brot, he invoked the High Priest’s plea “may your homes not become your graves” (“Ve’al anshei sharon Hashem Yerahem yehi ratson shelo ya’asu bateihem kivreihem.” See Ta’anit 22b) and the congregants prayed to God desperately during the closing services (Neilah) to open up His gates of Rahamim to them (Ringelblum). That is, the metahistorical stream continued, the mythic language of God’s actions fit together with the empirical realities of the present. Jewish Religious Practice Through the War: God, Israel and History by Gershon Greenberg 4 April 2001 Yad Vashem, Jerusalem |

The Jewish Cemetery of Skępe

| The Jewish Cemetery

in Skępe, Poland dates back to just before 1850

(Virtual Shtetl). A cousin from Toronto had

visited the cemetery 20 years earlier, but only

after he located an older resident who knew where to

find it. Our cousin encouraged us to locate

and visit the cemetery. Thanks to a local town historian, Zyta Wegner and her husband Bernard, we were able to locate and visit what is left of the old Jewish Cemetery. To get there one leaves the town square on Rynek (the location of many Jewish businesses before 1939) and take Dobryzyńska street traveling southwest out of Skępe. After crossing a small creek you bear right on Rybacka and pass a couple of homes on the right. After the last home you enter an area of woods and come across a small, dirt road on the right which enters the woods and quickly descends to another dirt road (Aleja Spacerowa) which hugs the southern shore of Jezioro Małe, which the cemetery overlooks from its hillock location. One can park your car at the intersection of the dirt access road from Rybacka and Aleja Spacerowa, find the path to the left, and follow it up the hillock. After a short distance you will find a small foundation - the only remnant of what was once the resting place of Skępe’s Jews. Except for a few depressions in the soil there are no other indications that this was sacred ground: no matzevot remain to indicate the location of one’s family members. However, the foundation to a small building sits atop the hillock in a prominent position looking out over the lake (Jezioro Małe). At the time of our visit we wondered if it had once been used to prepare a body for burial. A follow up interview with an older, former resident, Stanisława Nadrowska of Skępe in late May, changed our understanding. According to her the building was a monument (Ohel) to a prominent Jew of Skępe - probably a rabbi. Standing by the ohel foundation, shaded by large trees and a picturesque view of Skępe, our guide, Bernard Wegner, pointed to another hillock immediately to the northeast and informed us this was the original Jewish Cemetery from the 1800’s. After it was filled, the Jewish community purchased additional land to accommodate future burials. Skępe has a similar history with many other Polish towns. Even though it is reported the Germans destroyed the cemetery after 1939, it was local townspeople who collected the matzevot for use in their foundations, sidewalks, and steps. Until a short time ago the path leading from a home on Rybacka down to the lake had steps made from the matzevot of the cemetery. These cemetery markers recently disappeared and their whereabouts are unknown. |

|

|

| The

path alongside the cemetery in Skępe |

The

remains of an ohel in the cemetery |

| A

view of Skępe from the cemetery |

More

of the cemetery from the ohel |

| The

oldest part of the Jewish Cemetery Cemetery Photos

by Roberta Fleishman

|

Matzevot

had been used as steps between the lake and this home

but were recently removed |

Compiled by Roberta Fleishman and Mike Smith

roberta.fleishman@gmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Roberta Ann Fleishman

roberta.fleishman@gmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Roberta Ann Fleishman

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., The home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.