|

Tracing My Roots in Rakishok Sorrel KerbelPart 2 |

So it was with mixed feelings that my husband Jack and I drove to Rokiskis from

Kaunas in September 2002, a pleasant two-hour drive through forested, fairly

flat countryside. There was very little traffic on the roads, occasionally some

cars and even the odd horse and cart. We were told that many poor Lithuanians

had gone back to the days of the horse and cart because of the rising cost of

petrol, now no longer subsidized by the Soviet state, but still half the price

we paid in the UK.

I was armed with the details Julia Holzer (neé Segal) had given me in London

some ten years before, kept in my diary all this time. Julia had been in the

same class as my aunt Liebe-Leike at the Hebrew pro-gymnasium in Rakishok. She

left Lithuania only in 1968, so she remembered it all clearly.

My reference points were the house of the Graf (now a hotel) and the imposing Catholic church. Counting left, the fourth house, a triple-storeyed narrow wooden building on a corner, with a wooden slatted roof and brick steps leading up to the front door, was where my mother grew up. It was unchanged. The garden in front, at the side, and in the back, is well-kept and planted with fruit trees and flowers. Reb Bezalel’s house stood empty, for sale.

We peered through the windows into the front room. This was where Rebbitzin

Sorke sold some household supplies, such as yeast and candles. She had the

monopoly on selling yeast, an important perk for rabbi’s wives at that time,

bringing in a few gruschen to supplement their resources.

The Batei Midrashim, (synagogue and houses of study) were burned to the ground

in July 1941.

In my mother’s day, there were conveniently located on the market square a well

and a large pump, surrounded by a low wall. Attached to the pump was a tin can,

which passers-by could use to quench their thirst on a hot day. At the foot of

the pump was a trough of water for cattle and horses. During my visit in 2002,

there was on this site a Soviet-style memorial to the anonymous war dead, some

twelve foot high in Soviet-style pink granite.

Like many other Soviet-era monuments, it is has been removed.

We followed Julia’s instructions to find the Russian Orthodox church (tzerkve); opposite it was the park (bulvar) where the horse market used to be. Still a park and children’s playground. On the corner the large house facing the park was the Jewish orphanage, now a private dwelling. Turn left, and count three houses to a single-storeyed wooden house, the home of the Kruk (Kriger) family (See photo at http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/rokiskis/Kriger.htm), who left for Cape Town in 1931, despite a warning from the Lubavicher Rebbe not to go to this “treife” (unclean) country! (The Rebbe himself escaped to the USA in 1940, when the Soviets closed Jewish religious institutions.)

It was all there, little changed. The small wooden houses of the Jews are

occupied by more prosperous Lithuanians, mostly with double glazing, running

water, and neat gardens. A van was delivering loads of firewood, so I guess they

still depend on wood fires. The alternative type of dwelling today is a flat in

one of the many ugly concrete Soviet-style blocks of flats situated on the outer

perimeter of town. The Jewish houses are in the centre of town, so it is not

surprising they are now highly desirable “bijou” townhouses.

I had carefully prepared a sentence from the Lithuanian dictionary asking the

location of the Jewish cemetery, and asked a woman in the well-stocked bookshop

on the relatively prosperous Kamayer gasse (now, Respublikos gatvė). I asked in

English, showing my page, and a well-dressed couple responded. They were driving

a newish German car and we followed them part of the way. Instead of leading us

to the old Jewish cemetery, on the western edge of the town, they instead led us

to the hamlet of Bajorai, which is northeast of Rakishok.

There, an old woman with a drab headscarf and poor teeth (probably no

more than my age) pointed us in the direction of a memorial with a sign written

in Lithuanian that translated into “Memorial to the Fascist Martyrs of the

Holocaust.”

Continuing along a winding road into the deep and lovely birch woods beyond Bajorai, we reached a path, on the right, to the “killing field.” It was here that more than 3,200 Jews died. They had been brought here from Rakishok and four hamlets, including Abel and Skopishok. They were rounded up shortly after the Germans arrived in late June 1941 and held for 6-8 weeks in a ghetto established for Rakishok area Jews in two barns of the estate owned by the Graf. A few escaped from the ghetto and fled to neighbouring farmers; they were mostly betrayed.

On August 15, 16, and 20, 1941, these Jews were marched some two miles from Rakishok, forced to dig their mass graves, and then shot and buried in seven large trenches, now concreted over. Today there is a simple memorial plaque in three languages. We were told that the post-Soviet Lithuanian State would not allow any mention of the fact that the Jews had been murdered with the willing collaboration of Lithuanians. (See photo at http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/rokiskis/Holocaust.htm)

It was quite a day. Jack and I quietly said Kaddish in their names. There were a few tired red flowers at the memorial, and the remains of a few Yahrzeit candles. It was eerily quiet in the woods, with only a youngster walking to the forester’s house further up the path.

The next day, having returned to Kaunas, we were met in the foyer of the Takioji

Neris Hotel (now, the

Park Inn by Radisson Kaunas)

by the guide we had prearranged. Chaim Bargman is the

Shlomo of Dan Jacobson’s Heshel’s Kingdom; an excellent guide who speaks five

languages, including Hebrew.1

Also waiting in the foyer was Czeslovas Rakevicius, 84 years old, tall and well

built. He is the son of the doughty peasant farmer whose wife (Czeslovas’

mother) was a patient of my mother’s brother, Dr. Israel Meirowitz.

Czeslovas explained that before the war, his mother had had an operation

in the hospital at Kaunas and became friendly with Jewish doctors there,

including my uncle. The Rakevicius

family wanted to help Jews and because their farm was very isolated, far off the

beaten track, it was put on a list of safe houses.

They hid my aunt, Liebe-Leike, who had escaped from the Kovno ghetto, and

her son, then 11-year-old Aharon Barak, who had been smuggled out of the ghetto.

An article in the 23 July 1993 edition of the Jerusalem Post reported

on the ceremony at Yad Vashem where they were honoured as righteous gentiles. It

tells of how Zvi Brik (Barak) placed his son in a potato sack and smuggled him

past a bribed guard out of the Kovno ghetto to a waiting wagon.

In all, this tactic was used to save about 100 children.

(The stories of some of those children is told in Smuggled in Potato

Sacks, by Solomon Abramovich and Yakov Zilberg (Vallentine Mitchell 2011.)

Those not smuggled out were murdered in the March 1944 Kinderaktion.

|

|

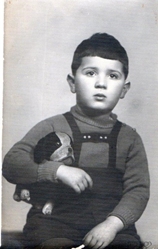

Left:

Zvi Brik (Barak) was the deputy manager of a

slave-labor shop in the Kovno ghetto where uniforms for Wehrmacht soldiers were

sewn. He managed to get his son Aharon out of the ghetto in a sack that was

thrown onto a horse-drawn cart.

Right:

Photo of Aharon Brik (Barak) at four years old.

Initially, Aharon was hidden on the farm of a righteous gentile, Jonas

Mazuraitis. Later, he was hidden

with his mother, Liebe-Leike Barak, on the farm of the Rakevicius family, who

courageously saved 25 Jews. A

remarkable and noble family.

Liebe-Leike told me that she had feared discovery at the Rakevicius farm because of her pronounced Jewish looks. So the family created a hiding space of one-and-a-half metres square behind a false wall in their living room and she lived in that confined space with her son for nearly two years. Food was passed to them and she used the time to teach her son everything she knew.

Czeslovas agreed to show us the site of his family’s farm, which is deep in the countryside, 84 miles west of Kaunas, near Paupys and Raseniai. Quite a trip on dirt roads. But we were pleased to do it because we heard from him, via the guide, the story of how the Rakevicius family became involved in hiding 25 Jews.

Before continuing, I would like to note the singular accomplishments of Aharon

Barak, the rescued child. From 1975

to 1978, he was the Attorney General of Israel.

In 1978 he was the principal drafter of the Israeli-Egyptian agreement at

Camp David. In 1995 he became the Chief Justice of Israel – the head of the

Supreme Court, a position he held until retiring in 2006.

Since then, he has been a professor of law at the Herzlia

Interdisciplinary Centre.

Ari Shavit tells Aharon’s story in My Promised

Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel, Spiegel & Gran, New York (2013),

at pages 142-145, 155-157, and 162, where he describes Aharon as “a brilliant

liberal jurist who has reshaped Israeli jurisprudence, and is admired

worldwide.”

It was only in 2005 that

Aharon first spoke publicly about his escape from the Kaunas ghetto.

At that year’s Yom Hazikaron ceremony in

Jerusalem, he began and ended his address by quoting from Zechariya 3:2 and Amos

4:1, “I am a brand plucked from the fire - in whom the spirit of man and of the

people breathed life, a life of freedom and of the recognition of the dignity of

every man, a life that aspires to achieve justice (righteousness) and the rule

of law.”

He told of the 5,000 children of the ghetto who were

taken from their parents and murdered in cold blood. “Few survived. I was among

them. In the ghetto the high-pitched voices of children were no longer heard.

”

With reference to the two Lithuanian farming families who saved him, he said “They were pious non-Jews who brought us to into their homes.” Continuing, he said:

In August 1944 we were freed

by the Red Army.

My father survived in one of the ghetto

bunkers. ... We crossed Europe on a goods train that was carrying coal from

Bucharest to Budapest.

There we celebrated the end of the war. We

crossed on foot the border from the Russian sector of Austria to the British

sector, and continued on from there to Italy. In 1947 we came to Israel. Slowly

Arik Brik became Aharon Barak.”

What lesson did I learn from all this? To what extent

have these events formed my Weltanschauung [philosophical view of the

world]? ... the Germans and their helpers sought to turn us into dust and ashes.

They sought to take from us the human dignity that is within us. ... the Germans

and their helpers succeeded in murdering many of us. They did not succeed in

taking from us the image of man that is within us. ... in our state we must

behave towards the non-Jew as we would expect them to behave toward us. We must

not fail the minority group.

It was not easy to find the location of the Rakevicius’ farm.

After the Soviets had recaptured Lithuania, the farm was collectivised

and the family relocated to Kaunas. A Soviet program to reduce the risk of

flooding in the countryside had resulted in both the Rakevicius and Mazuraitis

farms now being entirely under water - part of a lake for farming carp - and you

could see nothing but lake. We lost our way a couple of times, but even that had

its compensations. We visited a few of Czeslovas’ former neighbours, who greeted

him warmly. It is poor subsistence farming; small ramshackle wooden houses, with

corrugated-metal or wooden roofs, outside loos replete with newspaper, hand or

horse-drawn ploughs, covered wells, and small areas of land with just one or two

cows. Mostly flat swampy land fringed by trees, and the odd cormorant diving for

fish.

Then we visited the Ninth Fort outside Kaunas and the memorial to the “Killing Fields,” where they marched the sick and elderly, and later everyone from the ghetto except for a few escapees. Aharon Barak’s father, Zvi Brik, a well-known Zionist leader in prewar Kovno, was a member of Matzok and manager of one of the large workshops in the ghetto. He was able to organise clandestinely the building of a maline (ghetto slang for bunker) near the river, outside the ghetto. Their maline saved eight people, including Rochel (Rachel), my mother’s youngest sister and her husband Mendel Kalwaria, Mendel’s brother and his wife, and Zvi Barak.

Toward the end of the ghetto’s existence, the Germans searched for Jews in

hiding, blowing up every stone house, and setting fire to every wooden one. The

ghetto burned for several days until it was completely destroyed. Mendel, who

was an engineer, had designed and constructed the maline with air

vents. This crucial feature enabled those in the maline to avoid death

by asphyxiation when the ghetto was burned. Twenty-five others survived in

another maline inside the ghetto.

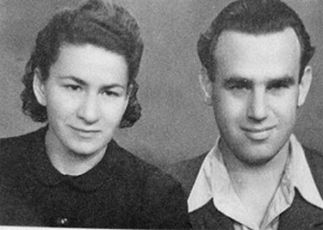

|

Rachel (youngest daughter of Reb Avrom Meirowitz) and her husband, Mendel

Kalwaria, survivors of the Kovno ghetto, in Bari, Italy, awaiting a ship to

Palestine, December 1945.

My uncle, Dr.

Yisroel Meirowitz did not survive the war.

In 1944 he had volunteered to go from the ghetto on a medical call and

was then shot.

In the small museum at the Ninth Fort we saw the

official list pinned up by the Nazis stipulating that the named persons were to

report for duty as Yiddishe Ghetto Polizei.

The 43rd and last name was “Meirowitz, Josef” (my mother's older brother

who later settled in Brazil to avoid any enemies he might have made in the

ghetto.) 2 3

My mother’s brother, Josef Meyerowitz, who was ordered

to be kapo number 43 in the Kovno ghetto, the last name on the list.

He was freed when the Russians liberated the

ghetto and later settled in São Paulo, Brazil, near our Gelcer, Zamet, Kagan,

and Gorenstein cousins. This picture may have been taken aboard the ship to

Brazil.

Then back to visit the Archives in Kaunas. They have the tax returns of various

shtetlach from 1850-1915; but rabbinical families are no good because they were

exempt from paying tax! The office was like something from Kafka – books with

yellowed pages piled high up to the ceiling, in cupboards, and on rickety chairs

and tables.4

In researching this article, I came across a tiny box-Kodak photograph from the

1930s of my great-grandfather, Rabbi Bezalel Katz, his son-in-law (and my

grandfather) Rabbi Avrom Meirowitz, and Bezalel’s nephew, Rabbi Shmuel

Yalowetsky (later, Samuel Yalow).

(A copy of the photo appears on the first page of this article.)

Rabbi Yalow received smicha

from Reb Bezalel and shortly thereafter emigrated to live and serve the

community in Syracuse, New York.

I also discovered a newspaper article from the 7 June 1943 edition of the

Syracuse Post-Standard, which reported on the wedding of Rabbi Yalow’s son

Aaron to Rosalind Sussman of New York. (As a result of her work in the field of

radio-immuno-assays of peptide hormones, in 1977 she became the first woman in

the USA to receive a Nobel prize in Medicine). The 1943 article quotes Rabbi

Yalow expressing the following hope to the bride and groom, “I have neither

wealth nor wisdom to bequeath to you. I can pass on to you but one thing,

mispor hayomim - the continuity of the generations, your link with the

immortal history of Israel.”

Footnotes

1 Dan

Jacobson, Heshel’s Kingdom, London, Penguin, 1999. Chaim Bargman lives at P.

Lukšio gatvė 37-22, Kaunas LT-49391, Lithuania.

2

See a record of their names in Sir Martin Gilbert’s The Righteous: the Unsung

Heroes of the Holocaust, New York and London, Doubleday, 2002.

3 Avraham

Tory, Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto Diary, Cambridge, Massachusetts,

and London, Harvard University Press, 1990, p. 522.

4 The

archives are open to the public daily, 10-1 and 2-5, for information on the

towns and villages of Kaunas province. If you need her, the archivist Vitaliya

Girčytė is very helpful and speaks excellent English,

v.gircyte@archyvai.lt.

For

information contained in Lithuania’s historical archives (in Vilnius), use

Istorijos.archyvas@centras.lt.

Back to Yiskor Plus

Back to Main Page

Copyright RokiskisSIG 2018