Tracing

My Roots in Rakishok

By

Sorrel Kerbel, D.Phil.

Editors’

Note

(Philip Shapiro): Dr.Sorrel Kerbel’s

great-grandfather, Rabbi Bezalel Shlomo Ha-Cohen Katz

(1843-1939), was a

prominent Hasidic rabbi in Rokiskis and the story of his family

provides a

glimpse of Jewish life in that shtetl from the 19th

Century until

its destruction in 1941. This article first appeared in two

instalments in Shemot,

the journal of the JGS of Great Britain, March 2003,

vol. 1.1, and

June 2003, vol.II.2.

Dr.Kerbel

is

the editor of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Jewish Writers

of the

Twentieth Century, 2003 and 2010, a reference work

providing essays on the

“Jewishness” or not of some 350 Jewish novelists, poets and

dramatists all

around the world. She received a D.Phil. in English literature

from the

University of Cape Town. She taught English literature at the

University of

Port Elizabeth, where she and husband Jack lived for 24 years

before emigrating

to London. They, their three children, and eight grandchildren

live in the UK,

where she is an independent researcher and reviewer. She

has also worked

for some years in London with Holocaust survivors through Jewish

Care.

The

original

version of Dr.Kerbel’s article, “Tracing My Roots in Rakishok”

was published on the Rokiskis Kehilalinks website.

For

this publication, she has updated her article. Dr.Kerbel

holds the

copyright to this story, which may not be used without her

permission.

Author’s

Introduction

to the Updated Article. As a result of the publicity

generated by the publication of my article in 2003, I discovered

a very special

relation in Cape Town, Attie Katz. This updated version is

dedicated to

him and to the honoured memory of all of my family who perished

at the hands of

a few Nazis and their willing Lithuanian collaborators in the

Lithuanian Shoah.

A new exhibition currently on show (2017) in Berlin about Litvak

Jews for the

first time acknowledges German responsibility for the “deaths by

bullet” in

Lithuania.

I

would like to use here a quotation from Roger Cohen’s essay, The

Girl From

Human Street, which was dedicated to his mother (New

York Times,

April 1, 2016). “Every Jew of the second half of the 20th

century

was a child of the Holocaust. So was all humanity. Survival

could only be a

source of guilt, whether spoken or unspoken. We bore the imprint

of departed

souls … I wanted to understand where I came from.” This

article, “Tracing

My Roots in Rakishok,” reflects my personal quest to

understand where I

came from and to remember so many names from the silenced past.

I

am grateful to many for helping me update this article,

including, but by no

means limited to, my husband Jack, my children and

grandchildren,

Shemot,

JewishGen’s Yizkor Book Project, Philip and Aldona Shapiro in

the USA, Giedrius

Kujelis of the Rokiskis Regional Museum, and my many friends and

family who

helped me organize genealogical details, namely (in alphabetical

order), Cookie

Epstein, Ada Gamsu, Dorothy Gelcer, Julia Segal-Holzer, Gerry

Hornreich, Anne

Martin, Ros Romem, Paul Teicher, the Todres brothers and my

Windisch family.

One of our most amazing new links is to my favourite Yiddish

playwright and

novelist, Sholem Aleichem, and his daughter Bella.

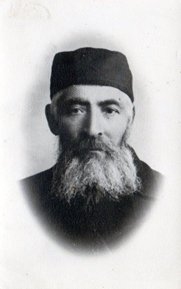

Reb Bezalel Shlomo

Ha-Cohen Katz (centre) with his son-in-law, Reb Avrom Meirowitz

(left), and Reb

Bezalel’s nephew, Rabbi Shmuel Yalowetsky. The photograph

was taken in Rakishok

on the eve of Rabbi Yalowetsky’s departure for the USA, where he

would be known

as Rabbi Samuel Yalow of Syracuse, New York. The two

younger rabbis

received smicha from Reb Bezalel. Rabbi Yalow is

wearing a new

straw hat to show off his role as a soon-to-be American.

Part

1

My mother’s

grandfather, Reb Bezalel Katz, “cheated” the Nazis by dying in

July 1939, three

months before the start of World War II. Reb Bezalel lived to

the grand old age

of 96. His 93-year-old wife Chaya Sora (nee Yalowetsky), for

whom I am named,

followed him a few weeks later to a peaceful grave. (She was

affectionately

known as Rebbitzen “Sorke.”) But the family was not

able to erect

gravestones to their memory, as my mother, Nechama

Meirowitz-Stein, explains in

her essay in the Rakishok Yizkor book, “A Few Words in

Place of a

Tombstone.”1

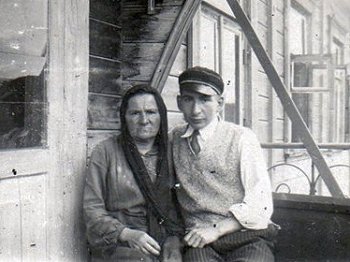

This is the only

known

surviving image of Rebbetzin Sorke, the wife of Reb

Bezalel Katz, for

whom I am named. She is shown here with her grandson,

Israel Meirowitz,

on the enclosed porch of their house, which stood facing the

market square of Rakishok.

Rakishok, which is 13 miles

from the Latvian border, was

the largest shtetl in the northeastern region of Lithuania and

was the district

capital after 1915. It was a flourishing spiritual and

business centre

for Lithuanian Jewry. The Jewish population fluctuated in number

according to

the exigencies of the times. In 1847, the Jewish population was

593; in 1897,

it was 2,067, constituting 75% of the general population; in

1914, on the eve

of the First World War, it was about 3,000, out of a general

population of 3,829.

In 1923, following the upheavals of the First World War,

2,013 Jews lived

there, constituting about half of the general population. In

1939, there were

3,500 Jews, constituting about 40% of the general population.2

Rakishok had excellent rail

connections to Dvinsk,

Riga, Panevezys (Ponovezh), Siauliai (Shavli), and

Kaunas (Kovno)

which facilitated trade. What contributed to its special

development and

stability were its long-standing and well-established markets

for many kinds of

products, such as flax, seeds, furs, grain, eggs, butter, fruit,

poultry,

lumber, and meat. During this era, there was also intensive

trade by Rakishker

Jewish merchants in raw hides and skins. Most Jews were traders

and peddlers,

but there were also artisans, such as tailors, shoemakers,

hat-makers,

butchers, bakers, metalworkers, and clockmakers. Several hundred

Jews worked in

small Jewish-owned industries like the tannery, flour mills,

sausage factory,

casting factory, and electric station. Most of the town’s

doctors and pharmacists

were Jewish.3

Rakishok developed from an

estate owned by the Polish

house of Kroshinsky. The widowed Princess Helena, the last of

that family,

married Count Tizenhoff, and Rakishok passed to the

family of the Counts Pshezdetsky. The impressive St. Matthew’s Catholic

Church, which overlooks the market square, was built between 1866 and 1885

upon the initiative of Count

Reynold Tizenhoff. It is positioned to have a clear view

beyond the

market square to the front of the Tizenhoff manor house, one

kilometer to the

east. Then, as now, its towering spire dominates the

landscape.

Reb Bezalel

(1843-1939)4 was born in Rakishok and lived

“for as long as

anyone could remember” on the Kamayer Gasse (now,

Respublikos

gatvė). This street originally led directly south from the

market square

to Kamai, which is 11 miles away. Across from Kamayer

Gasse

the market place would particularly bustle on Mondays, which

were market days,

on Sundays, when churchgoers would patronage Jewish shops, and

especially on

fair days, when thousands of peasants would come to town. Near

his Kamayer

Gasse house were the Batei Midrashim (houses of

study) on Synagogue

Street (now, Sinagogų gatvė). From the time that Lithuania

became an

independent country, the synagogues were painted, respectively,

the colours of

the Independent Lithuanian flag – the yellow one was for

scholars, the green

one was for community leaders, and the red one, which was the

largest, was for

the general community. Prior to the First World War, there

was a fourth

synagogue nearby on Pirties gatvė (Bath Street) that had been

built for use by mitnagdim.

That synagogue had its own mikveh (ritual bath).

During the First

World War, the mitnagid synagogue was destroyed by a

fire. Of the

many Jews who fled either to Russia or Germany during the war,

the relatively

few mitnagdim who returned to Rakishok could not

afford to

rebuild their synagogue. As a result, it was agreed that

the great

(“red”) synagogue would be used by everyone in the community.

Near this area were

other buildings that were important for business, such as most

of the larger

shops for textiles and leather goods, flour storehouses,

warehouses, a bank,

and even a showroom of Singer’s Sewing Machine Company.5

The

bank, which was known as the Rakishker Yudishe Folkbank (in

Lithuanian,

“Rokiškio Žydų Liaudies Bankas”) was the Rakishok branch

of the Folkbank.

The Folkbank was established after the First World War

with assistance

from the Joint Distribution Committee (“Joint”), an American aid

organization,

and had several branches in Lithuania. (There were also branches

in six Balkan

countries).

Reb Bezalel was the

“official” rabbi of Rakishok, and met the first

President of Independent

Lithuania, Antanas Smetona6, on his visit to Rakishok

on the

occasion of the opening of the new railway station, circa 1920.

He stood, a

frail figure, on the festooned podium with the president and

Graf

Tizenhoff. Later that day; the President visited the

synagogue complex.

My great-grandfather Bezalel was a Hasid who gathered

around him other

rabbis of his persuasion, each with their own followings -

Lubavicher,

Babroisker, and Ladier. My mother describes her

grandfather as a

figure of great piety, modesty, and tolerance, who studied “Yom

ve’laila”

(day and night). He wrote many books and articles which

regrettably have gone

missing. He was also something of an expert in Hebrew, and once

wrote a much

praised letter in Hebrew to the director of education at the Rakishok

pro-gymnasium

(high school) which used Hebrew as the medium of

instruction.

This was the school where my mother and her sisters were

educated. Reb

Bezalel’s granddaughter Feiga married Josef Caspi who served as

the principal

of both the Tarbut Bet Sefer and Pro-Gymnasium.7

In the photo on left:

My mother Nechama (centre), with her sister Liebe-Leike

(Leah) far left

(with fringe). Photo on right: Joseph Caspi (centre)

with a

pro-gymnasium class. To the right of Caspi is my mother

Nechama and to

the right of her is her sister Liebe-Leike. In

the second row on the

left, wearing a white collar, is Julia Segal Holzer.

The Graf Tizenhoff

greatly admired my great-grandfather, who initially worked for

him as an

ironmonger and was for a short while his agent on the

estate. In 1931,

when the Lubavicher Rebbe Yosef Yitzchak Shneersohn

honoured Reb Bezalel

with a visit, Reb Bezalel met him at the railway station with a

carriage and

horses loaned by Graf Tizenhoff, and they drove through the town

to the

synagogue behind his house on Kamayer Street.

According to an

anecdote told by aunt Rochel Kalwaria, a non-Jewish neighbour

who was present

proudly told my great-grandmother, Rebbitzen Sorke,

“your Kaiser has

arrived.”

After working for the

Baron, Reb Bezalel received smicha (becoming ordained as

a rabbi) from

his father, Reb Yosef Ha-Kohen Katz, who was then the rabbi of Rakishok.

Reb

Bezalel served as a rabbi in Karsevke, (now, Kārsava,

Latvia, which

is about 82 miles northeast of Dvinsk (now, Daugavpils),

Latvia), where he had

a “guten nomen” (good name/standing). (This is a

reference to Pirkei

Avot (Ethics of Our Fathers) 4:13, in which it is

said that “there are

three crowns: the crown of Torah, the crown of priesthood, and

the crown of

kingship. However, superior to all of these is the crown of a

good

name.”) For his second rabbinic post he returned to Rakishok,

inheriting the rabbinic “kisei” (seat) of his father, Rabbi

Yosef HaKohen Katz.

My great-grandfather,

Rabbi Bezalel, and his wife Sara had a daughter and three

sons. Their

daughter, Asne Rifke (1876-1941), married my grandfather, Rabbi

Avrom (Abraham)

Meirowitz (1875-1941), who is discussed below.

Reb Bezalel himself

came from an important family. His father, Reb Yosef

Ha-Kohen Katz, was

born around 1828 in Rakishok and had six sons, some of

whose descendants

managed to escape to South Africa, Israel, Australia, and the

USA. Avrom

Leib, the eldest, was the great-grandfather of Dov Katz of

Pardes Hanna

(Karkur), Israel, Attie and Sheilah Katz of

Cape Town, and Ann

Martin of Johannesburg. Bezalel, the second son and my

great-grandfather, was

also the great-grandfather of Thelma Windisch of London, Aharon

Barak and Avi

Kalir of Tel Aviv, and Riki Hirsowitz of Sydney, Australia. The

descendants of

Berzik, the third son, established the jewellery store Katz

& Lurie in

Johannesburg. The descendants of Shmuel, the fourth son,

perished in

Lithuania. The fifth son, Yaakov Katz (b. 1879 in Rakishok),

married

Reisa Galbershtat of Rakishok (1879-1939). Their

son,

Chaim Tuvia Katz (1909-1990), was a founding member of Dafna (3

May 1949), a

kibbutz in the Upper Galilee of Israel. He and his wife Chaya

Shein Czarka had

two children, Tsofar Katz and Avigail, who live in Haifa.

The sixth son,

Shnuer Zalman (Shneyer Zalman) (b. 1881), died in Abel in

1941. Reb Yosef

also had two daughters, one of whom, Raisa Devorah, married Reb

Zecharya Alter

Abrahams (whom my mother called called “Avromtzik

Jossel”). Their son was

Chief Rabbi Prof. Israel Abrahams of Cape Town, who was the

father of Ros Romem

of Jerusalem.

Reb Yosef, too, came

from an illustrious family. He was the second of five sons born

to Reb

Meir Ha-Kohen Katz, who was born in Linkuva around

1795. Reb Meir

was serving as a rabbi in Rakishok when his second son,

Yosef, was born

there. Thus, the Katz family served as rabbis in

Rakishok for at

least a hundred years. According to family legend,

generations of Ha-Kohen

Katz rabbis served in communities in Lithuania for more than 300

years. The

five sons of Reb Meir Ha-Kohen Katz are a genealogist’s

nightmare because they

were each given different surnames at birth to avoid 25 years’

conscription

into the Czar’s army. The eldest was Shmuel Leib Ha-Kohen Kaplan

(b. 1808 in Rakishok,

whose descendant Valerie Mathieson from the USA provided

details of Shmuel

and his wife Taube Kuperman of Rakishok and their six

children, all of

whom died in Lithuania); the second son (my

great-great-grandfather) was Yosef

Ha-Kohen Katz; the third son’s name was not known to my mother,

though she

notes that he later became a rabbi in Linkuva, taking his

father’s place

(this may be the Rabbi Aharon Ha-Cohen who is mentioned on the

Linkuva Kehilla

website as having endorsed the collection of funds to assist

distressed Jews

after a large fire burned about 100 buildings, including the

community’s wooden

synagogue); the fourth son was the eminent science populariser,

Tzvi Hirsch

Ha-Kohen Rabinowitz (1832-1889); and the youngest son of Reb

Meir was called

Moshe Yaffe. (My mother notes simply that he was “a merchant,”

and therefore

did not have much “koved” (prestige) in her eyes.)

The fourth son of Reb

Meir Ha-Kohen Katz, Tzvi Hirsch Rabinowitz, showed an early

inclination for

mathematics and physics. From 1852, while studying in St.

Petersburg, he began

work on a comprehensive Hebrew-language project that was

intended to encompass

all the fields of physics. At length, one volume was

published, in 1867,

which was entitled, Sefer ha-Menuchah ve-ha-Tnuah (“The

Book of Rest and

Movement”).

Tzvi Hirsch also

wrote

Hebrew-language books on mathematics, magnetism, chemistry, and

steam-engines,

thus enriching Hebrew terminology in these fields and bringing

them to the

attention of Hebrew readers. He also published many articles in

Ha-Meliz

(“The Ornamentation”) and in several Russian periodicals which

he edited and

published, including Russki Yevrei (Russian Jews) from

the late 1870s

until 1885. All of his books were published in Vilna/Vilnius.

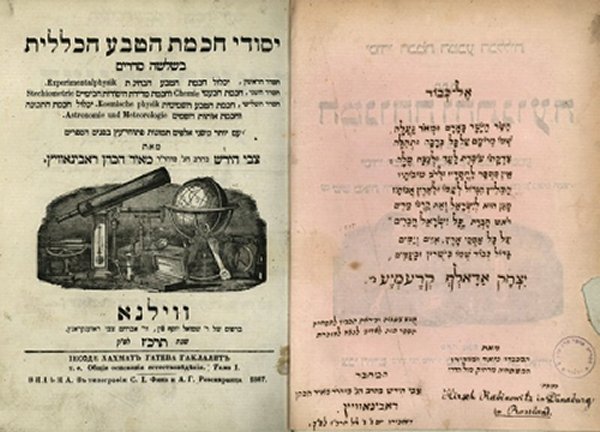

Title Page of Tzvi

Hirsch Meir HaCohen Rabinowitz’s “Yisodei HaChachmat HaTeva

HaKlalit,”

Vilna (1867).

As noted above, my great-grandparents, Rabbi

Bezalel and Rebbitzin Sorke Katz, had a daughter Asne

Rifke (1876-1941),

who married my grandfather, Rabbi Avrom (Abraham) Meirowitz

(1875-1941).

Avrom Meirowitz was the fourth child of Moshe and Rifke

Meirowitz of Karelitz

(Karelichi), a town 15 miles east of Novogrudek that was

in the province

of Minsk. Moshe and Rifke had 6 children, namely, Berl

David, the eldest,

whose family settled in Rhodesia and Israel; the second son

Yaakov, who

emigrated to the U.S., where there are many cousins; Ethel

Cohen, who died in

1941; my grandfather Avrom; Yudel, who died in 1941; and the

youngest, Meir,

whom, they said, was killed by the Cossacks. Meir’s wife

Machle (nee

Sachar) was from Kupishok and her brother, A. L. Sachar,

was the

founding president of Brandeis University. Her children

settled in

Israel.

Avrom Meirowitz

studied at the yeshivas of Mir, Slobodka, and Volozhin (where

his

study-partner at one time was the renowned Hebrew poet, Chaim

Nachman Bialik).

When my mother, Nechama Meirowitz-Stein, was born in Rakishok,

the

couple lived in her grandfather’s home because her father served

in the nearby

shtetl Skimiahn (Skemai, which is about 6 miles

northeast of Rakishok).

In early May 1915,

during the First World War, the Czarist government ordered the

Jews of central

Lithuania exiled to the interior of Russia – on two days’

notice.

Although the order did not apply to Jews in northeastern

Lithuania, many were

concerned about the approach of the war front. The family,

together with

most of the Jewish inhabitants of Rakishok, fled into

Russia for safety.

Unfortunately, Russia experienced two revolutions in 1917,

followed by a civil

war. It was only after (Soviet) Russia and the new

independent Lithuanian

republic reached a peace agreement that the Jewish exiles could

return to

Lithuania. My mother recalls that as a child of ten, when her

family returned

to Rakishok, they were welcomed back by the Lithuanian

townspeople with

“flowers, love, and honour.”

My mother Nechama

wrote in the Yizkor book that her father, Rabbi Avrom

Meirowitz, was a

wise man who was no stranger to world affairs despite having

lived in a

relative backwater. He was a mitnagid who read many

secular books. His

command of Russian and German, acquired on his own, led him to

read the great

literature of those languages, including the works of Dostoevsky

and

Tolstoy. My grandfather’s horizons went well beyond the

confines of the

narrow world of the shtetl. He was a founding member of the Rakishok

branch

of the Folkbank and served as the bank’s director in Rakishok.

In

addition, he went often to Ponovezh (Panevėžys),

where he sat on

a rabbinical arbitration board to resolve disputes among

litigants.

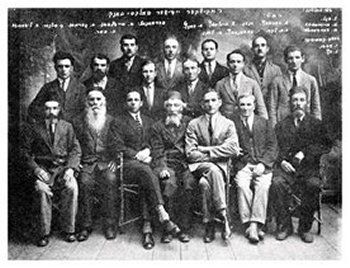

Rabbi Avrom Meirowitz

was the chairman of the Folkbank. He is shown

here, in the centre

of the front row, with other members of the management board.

First row,

sitting right to left: Shloime Arelovits, Hillel Eidelson, Abba

Leib

Dovidovits, Avrom Meyerowitz, Leib Segal, Zalman Milner,

Israel-Leib Snieg;

Second row, right to left: Isaac Panets, Chaim-Moteh Lekach,

Avrom Harmets,

Yudel Gafanovits, Hertze Lang, Yosef Caspi; Third row, right to

left: Velvel

Lipovits, Mr. Bar, Nahum Katz, Solomon German.

The marriage of my

grandfather, the mitnagid Rabbi Avrom, to my grandmother

Asne, the

daughter of the hasidic Rabbi Bezalel, reflects a good

deal of tolerance

on the part of the latter, who even permitted the young

married couple to

live in his household.

By the middle of the

1920s, with anti-Semitism growing in Lithuania, many Jews began

to consider

emigrating, especially to Palestine. The Balfour

Declaration had promised

the establishment there of a Jewish homeland. My grandfather,

Rabbi Avrom

Meirowitz, had a strong Zionist orientation (perhaps acquired at

Volozhin

Yeshiva, which was known for its espousal of Zionism).

This inclination

led him to join the Mizrachi - the National Religious

Party - within the

Zionist movement, and he appeared as a speaker at their meetings

and rallies.

As a result, understandably, he was less popular among the

ultra-orthodox Agudas

Yisroel circles.

Left photo: My

grandfather, Reb Avrom Meirowitz, the last rabbi of Abel.

Right

photo: My grandmother, Asne Rifke Meirowitz, with her two

grandchildren,

Josef and Ester Michelson, the children of her eldest daughter

Taube Mirkes.

All were murdered in Abel in 1941.

In 1928 my

grandfather

became the rabbi in Abel (Obeliai), nine miles to the

east. At a

rabbinical conference in Ponevezh in the late 1930s, he

warned his

audience of the imminent dangers of Nazism, saying they were

mistaken in

thinking Hitler’s objectives were confined to the destruction of

only German

Jews. This raised much criticism among the Agudah

delegates, and his

admonition fell on deaf ears.

Although Reb Avrom

possessed immigration papers for America, his wife, Asne Rifke,

refused to

leave Lithuania without her grandchildren. Sadly, he met his

death from an axe

wielded by a Lithuanian collaborator while standing on the

bima of the

shul in Abel, where all of the Jews of the village

were held in

August 1941. He was thus the last rabbi in Abel. Because

of my mother’s

delicate health, the truth of his death was kept from her, and

the sanitized

version she gives in her essay is not correct, according to my

mother’s last

surviving sister, Rochel (Rachel) Kalwaria of Kiryat Ono, Israel

(July 1995).

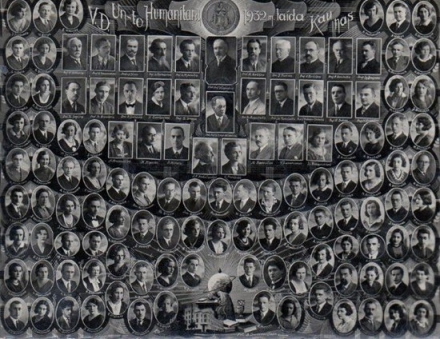

In this photograph of

the 1932 graduates from Vytautas Magnus University, my mother,

Nechama

Meirowitz, is shown on the next-to-bottom row, on the far

left. Immediately

to the right is her sister, Liebe-Leike Meirowitz.

Poor as they

were, the Meirowitz family was enlightened and determined enough

to send their

children to college. My mother Nechama received a B.A.

degree from

Vytautus Magnus University in 1932. Her two sisters,

Liebe-Leike and

Rachel, became, respectively, a teacher and a pharmacist, while

their brother

Yisroel (Israel) became a medical doctor. They would go off by

train from the

nearby Rakishok railway station to the University in

Kaunas where they

boarded with Rakishker landsleit. My mother told me how,

in winter,

their landlady would be sent a frozen barrel of veal or beef by

train, as

partial payment for their board. (Rakishok was an

important centre for

the wholesale meat trade.)

Photo of my mother’s

brother, Dr. Israel Meirowitz (front row, second from the

right), with

colleagues at a hospital in Kaunas. In 1944, while out on

a medical call,

he was shot dead.

In Lithuania, my

mother’s family and friends gave her the nickname “die

shvartze varona” (“the

black crow/raven”) because she forewarned of a dismal future for

Jews in

Lithuania and tried to convince them to emigrate. After her

graduation from

Vytautas Magnus University she left for Jerusalem, where she

married my father,

Nathan Stein, and then migrated once more (with my sister

Thelma) to Cape Town,

South Africa.

A boating party

in

peaceful times on Lake Obeliai. Fourth from the right is

Julia Segal

Holzer, my mother’s friend who was also saved in the maline

in the Kovno

ghetto. Third from the right is my mother’s brother, Dr. Israel

Meirowitz. Second from the right may have been Israel’s

fiancé, Miriam

Jaffe, from Kupishok.

Footnotes

1 Nechama

Meirowitz-Stein, “A Few Words

in Place of a Tombstone” in Yizkor-Book of Rakishok and

Environs, edited

by M. Bakalczuk-Felin, Johannesburg, Yizkor Book Publishing

Council, 1952, pp.

145-149. Most of the family information here was learned at my

mother’s knee or

contained in her essay. I am indebted also to Alan Todres of

Chicago and

Raymond Karpelofsky of London who helped me with the Yiddish

translation.

2 Nancy

Schoenberg and Stuart Schoenberg,

Lithuanian Jewish Communities, New York, Garland

Publishing, 1991, pp.

240-244.

3 R. Aarons

-Arsch, “Notes on the Economic Position of the

Jews in Rakishok.”

in Yizkor-Book of Rakishok and Environs, pp. 19-29.

4 The All-Russia

Census of 1897 gives

ages for Reb Bezalel and various members of the family which do

not coincide

with the ages presented here. For the purposes of this article,

I have chosen

to use the ages recorded by my mother in the Yizkor-Book of

Rakishok and

Environs.

5

A. Orelowitz, “Rakishok Before and After World War

I”

in Yizkor-Book

of Rakishok and Environs, pp. 7-18.

6 Antanas

Smetona (1874-1944) was the

president of Lithuania from April 1919 to June 1920 and then

from late 1926

until the end of the first Lithuanian republic. During

most of the latter

period, he ruled as an autocrat. Ostensibly and officially a

“friend of the

Jews,” he surprised the British Consul in Kaunas by describing

the Jews of

Lithuania as “active Communists” and “dishonest traders.” Masha

Greenbaum,

The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community

1316-1945, Jerusalem, Gefen Publishing, 1995, p. 279. On June 15, 1940, as the

republic succumbed

to Soviet annexation, Smetona fled to Germany, and a year later

moved to the

USA.

7 Feiga, my mother’s

cousin and the daughter of

Aharon Katz, married Josef Caspi (Serebrovitz), who wrote as a

Jewish

journalist using the name “Caspi.” He was born in Rakishok,

worked first

at the Folkbank (employed by Rabbi Avrom Meirowitz),

then as principal

of the Tarbut School and Pro-gymnasium in Rakishok.

Because of his

capitalist views, he was imprisoned in 1940 during the initial

Soviet rule and

released shortly after German occupation in late June 1941. He

then threw in

his lot with the Germans so that he could fight communism. He

was exempted from

wearing the yellow Star of David and allowed to live in Kaunas

outside the

ghetto and even to carry a gun. He was, in his own mind, “a

living legend who

will go down in Jewish history” (his words to the Council in the

Kovno

ghetto). He acted as an intermediary between the ghetto council

and the Nazi

commandant. In October 1941, he was sent to Vilnius. In June

1943, back in

Kaunas, he was shot by the Nazis together with his wife and two

daughters.

Shortly before his death Caspi addressed the Jewish council of

the Kovno

ghetto, “You entertain illusions of survival. I know that if I

survive, it will

only be by chance.” (He is shown in the photo above of the

pro-gymnasium class

with my mother and her sister Leibe. An account of this

story appears in

Avraham Tory’s Surviving the Holocaust: The Kovno Ghetto

Diary,

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, Harvard University Press,

1990.

Click here to continue reading Part 2 of this fascinating story.

Return to

Main Page