The Life and Death of a Shtetl

by Howard Margol (with the help of Willie Mann)

Pushelat (Pusalotas), a small village in the central part of Lithuania, has existed for hundreds of years. It is located about 21 miles Northeast of the fifth largest city in Lithuania, Ponevezh (Panevezys). It is not known in what year the first Jews arrived in Pushelat but according to the 1816 census, Jews were living there at that time. On the 1882 census, 811 Jews are listed as living there. By then, it was more of a shtetl rather than a village. In 1897, 920 inhabitants were Jewish out of a total population of 1,200. After the turn of the century, emigration began to have its effect and the number of Jews living in Pushelat was about 500. In June 1941 when the German army invaded Lithuania, approximately 200 Jews remained in Pushelat. Today, the population of Pushelat (now Pusalotas) is 1,100 and no Jews.

A good friend of mine, Willie Mann of Johannesburg, South Africa was born in Pushelat in 1913 and spent the first fifteen years of his life there. What follows is mainly Willie's story and his remembrance of what life was like in Pushelat.

Willie Mann's house - this is the house Willie was born and grew up in. The house next door, painted yellow, is the house where Willie's relatives, the Bermans, lived.

I want my grandchildren to know how Zaida managed to live and grow up without a motor car, television, computer, electricity, running water, inside sewerage and even Coca-Cola, for Pushelat had none of these 'musts'. Life was quiet and primitive. News from the outside world reached us via the Kovno daily “Die Yiddishe Shtime” to which three or four families would subscribe jointly. We would wait for it with much anticipation, eager for the “news” which was often days or even weeks old.

There was not a single motor car in the shtetl - and all the traffic to Ponevezh had to go by horse and cart during the summer and by sleigh in winter. During my time there was no railway or bus service. Ponevezh, the fifth largest city in Lithuania, was a great city of learning and commerce. It was famous for its outstanding Yeshiva and the great Rabbi Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, who later transferred the Yeshiva to Israel. When the odd car did pass through Pushelat the children ran after it in great excitement. It had no doctor or hospital, so for minor ailments we used to go to the only chemist, who was a Russian. For serious illnesses we had to travel to Pumpian (Pumpenai), only four miles away, where there was a Feldster - an unqualified doctor - or to Ponevezh where there was a Jewish hospital. In charge of this hospital was the famous Dr. Shachna Mer who was one of the few Jews in Parliament, the Seijm.

When my brother Zorach - a brilliant scholar at the Ponevezh Yiddish Mittel School - was home for the school holidays and for some reason decided to climb the roof of our house and fell down breaking both his legs, my mother began frantically looking for transport. My father and I were in South Africa by then, so after much panic he was rushed to Pumpian. The Feldster was not of any great assistance so my brother was transported by horse and cart to Ponevezh where he spent months at the Jewish Hospital. Gangrene set in and. he suffered a horrible and painful death. My mother was devastated and it took her months to get over this tragedy. When she arrived in South Africa she would not talk about it and would not allow any of us to name a child after him

During our time there were about forty families living in the shtetl and our elders told us that prior to World War I there had been over a hundred families in Pushelat. Mass emigration began, mostly to Amerike , as the Russian Czar, Nicholas II, conscripted Jews into the army, forbade them to live in Russia proper, and generally made life difficult for us. America at the time had an 'open door' policy and anybody who could write a European language could enter the country. Yiddish was considered to be one of these languages.

In 1911, two years before I was born, a major fire occurred in Pushelat. The wooden synagogue was destroyed and 77 Jewish houses sustained damage. Jews from Pushelat, living in America, sent money to rebuild the synagogue. A decision was made to have the Rabbi, Ruvin Brug, hold the money until a new synagogue could be built. Rabbi Brug had graduated from Vilnius University as a pharmacist. The shtetl could not afford a full time Rabbi so Rabbi Brug supported his family by being a pharmacist in Pushelat. Lithuanian burglars found out about the money being held by Rabbi Brug, robbed him, and murdered him and his wife Frida in the process. Their two sons, 4 year old Mejer, and 2 ½ year old Israel, survived. Today, Rabbi Brug's grandson, Ehud Barak, is the Prime Minister of Israel.

The three main streets in the shtetl had no paving, sidewalks, names nor house numbers so post had to be collected at the post office. The postmaster was Mr Beinarawitz, a Lithuanian, and his house was near ours. His son was born blind and he became my constant companion, speaking only Lithuanian. The streets were sandy and passable in summer but in spring when the snow melted it was most unpleasant as blotes developed and it was heavy going for the carts.

As far as 1 can remember there was only one telephone in the whole Jewish community, at Isaac Frank's house. Isaac was the Gabai of the shul, a very prominent man, and in case of an emergency he allowed us to use the phone. In my time there was no Rabbi as the community was small and poor. Almost all of the houses were built out of wood, as solid logs were cheap and available, as was labour - no trade unions then. The roofs were made of solid wood but this was not always so. Originally, the houses had thatched roofs but the shtetl learned from bitter experience that the thatch caught on fire very easily. Today, in Pushelat, the roofs are made of tin. There were also a few brick buildings, one of which belonged to our cousin Velvel Witten, a well-known poet. Another belonged to the Gillelovitz family, a house full of girls, so we usually congregated there. The building even had a balcony - the only one in the shtetl.

At the top of the marketplace was the big Catholic Church - the Lithuanians were all Catholics. The church was surrounded by a vast cemetery, which in turn was surrounded by a high stone wall. We were scared of the church but I sneaked in once or twice. The icons, religious pictures and other relics overawed me and it was all so strange. Across from the church lived the priest, Gallech, on a huge estate but he did not worry us too much. Our relations with the Lithuanians were cordial and there were no pogroms in our shtetl during my time.

The main centre of activity was the shul - a solid two-storey brick building which was the heart of the shtetl. This was the new shul that was completed in 1913 after the wooden synagogue burned down. The main hall had two large tiled stoves that were always lit during winter, as it was extremely cold. This hall was only used on Shabbat and Yomtov. For daily prayers we used a small room heated in winter with ready-cut wooden logs - there was always a tall stack of them in the open yard - as Lithuania had no coal mines. Prayers were held three times a day and we boys were expected to davven every day, which we duly did. The shul had no toilets, as there was no running water in the shtetl and no indoor plumbing.

To the left of the shul was a large garden. Next to the garden was the Berman family house and our house was next to it. The shul has many wonderful memories for me. We boys used to climb up to the loft from the woman's section and catch pigeons that had a nest in it. I did it mostly with my best friend, Hilke Koton, who unfortunately died in Johannesburg at an early age. The “shames” used to chase us and it was always great fun getting away.

My Bar Mitzvah presented no problem and I did not have to practice for it or take lessons, as all of us knew the Torah well. My father was already in South Africa and my mother baked lekech and made kichel and herring. She bought two or three bottles of lemonade (no Coca-Cola in those days!) and everything went off well. No presents were given nor expected.

The shtetl was comprised mainly of Jews except for the municipality - the postmaster, the teachers and the single policeman as the Lithuanians all lived on plots outside the shtetl. Only on Sundays and Christian holidays was it invaded by hundreds of peasants who came to attend church services. They used to leave their horses and wagons in the Jew's yards and each Jewish family had their regular customers. Into our house they came in their Sunday best, went to the “small toilet” in the yard and did the shopping in our grocery room run by my grown sister and myself. Ma was a very enterprising woman and expropriated a quarter of our house for a press and dyeing business. The peasants used to bring their homespun and hand-woven cloths for her to press, which brought in some Lits. Unlike Henry Ford, she used all colours. This was the only one in the shtetl and she was extremely busy. To this day I do not know how the press worked.

We had a large house according to Pushelat standards, with a big kitchen and large oven heated by wood, where Ma baked the daily bread, “kitkes” on Friday, and “cholent” for Shabbat. In the wintertime, some of us would vie for the privilege of sleeping on top of the oven. This was sheer bliss. Next to it was one big bedroom with three beds so the boys had to sleep two to a bed, head and feet at opposite ends. Since we kids did not bathe that often, it was neither very pleasant nor comfortable. The next room, a quarter of the house, a large stove, a big table for us kids to do homework and more beds for our parents, sister and the other boys. We also had a big cellar under the house where we kept potatoes, cucumbers and other vegetables for the winter.

Besides being a large family - seven boys, one girl - we also had Ma' s mother, blind ever since I can remember, very skinny and totally bedridden. She stayed with us all the years I can recall and died only a short time before I left for South Africa. She must have been close to a hundred. Besides all of us we had a girl cousin who was very poor and often slept at our house. She now lives in Israel.

In order to bathe, Ma used to heat up water from our own well on Fridays. (This water was not drinkable). We used to bath one after the other. The communal bath outside the shtetl was only used four or five times a year, before the Yomtovs. Thursdays were for men and Fridays for women. Before Pesach huge pots of boiling water outside the building were used, kashering pots and pans and cutlery tied up with string. There was no Lux or Palmolive soap, only homemade kind. Jewish weddings were always exciting and festive for the entire shtetl. In 1922, Dinah, one of six daughters of Yossel (Joseph) and Mara Rocha (Schemer) Gillelovitz, married Beryl Melamed from Pagiriai, son of Nachema and Chana. Dina's brother(s), Chaim, was in the Lithuanian Army stationed in Ponevezh. He came to Pushelat for the wedding and brought with him a Lithuanian Army band. I do not remember whether they arrived in a vehicle of some kind or a horse and wagon. I do remember them starting to march down the street in Pushelat, playing very stirring martial music. All of us kids fell in behind the band and marched with them. It was a very exciting time in Pushelat. All of the Jews as well as hundreds of Lithuanians came to watch them march and to listen to the music. It was the only wedding ever held in Pushelat that had a band play music. A year ago, my friend Howard Margol in Atlanta, Georgia sent me a photograph taken at the wedding. Fifty-six people were in the picture including the Army band. There I was, sitting on the ground in the front row.

PUSHELAT WEDDING PICTURE – MARCH 31, 1922

ROW I – (sitting on the ground) – (1) Yente, daughter of Minda (Schemer ?) (2) Chaim Gillelovitz (3) Teacher (4) ? (5) ? (6) Abraham Gillelovitz (7) Rashka Gillelovitz (8) Marka Gillelovitz (9) Chaya Gillelovitz.

ROW II – (1) ? (2) Husband of Minda (Schemer ?) (Yente’s father), (3) Minda (Schemer ?) (4) Joseph Gilelovitz, father of the bride. (5) Mera Roche Schemer Gilelovitz, mother of the bride. (6) Dina Gilelovitz, the bride (7) Beryl Melamed, the groom (8) Chana Melamed, mother of the groom (9) Groom’s brother-in-law (10) Groom’s sister.

ROW III – (1) Rivka Gilelovitz (2) ? (3) ? (4) Doba Shul (5) Rivka Shul (6) Hanna Gilelovitz

ROW IV – (1) ? (2) Rivka Shul’s mother (3) Bella Gilelovitz

ROW V - ?

NOTE: in the picture but not identified – Nochemia Melamed, father of the groom.

Gilelovich-Melamed Wedding in Pushelat - 31 March,1922 - Beryl Melamed (age 33), from Pagiriai, son of Nochemia and Chana, married Dina Gilelovich (age 23), from Pushelat, daughter of Yossel and Mera Rocha (Schemer). Schochet Moise Abram Kulber officiated. (Pushelat had no Rabbi at the time).

As the shtetl had no bioscopes or theatres, we made our own entertainment, mostly Yiddish plays. Our cousin Velvel Viten and our sister were main organisers and I well remember the following plays. King Lear, Yankel der Smid and the very popular one, Motke der Ganaf. Velvel roped me in at the age of twelve as the secretary of the jury. It was all in good fun.

Yankel the SMID - Pesach - 1935

There were only four or five in our age group as the others emigrated soon after barmitzvah. There were dozens of girls, so we boys were in great demand. In summer, Friday and Saturday nights were the highlights of the week for us-young boys and girls. We used to go for walks in the moonlight, past the cemetery, past the church for want of anything better to do. I remember those walks, full of innocent fun and much laughter . . . the joys of youth! Also, the girls and we boys walked to the big bridge on the river, halfway to Pumpian and swam there. No bathing costumes were available or necessary as the boys swam on the right side of the bridge and the girls on the left. We had lots of fun. In wintertime, we used to go on sleighs in the street, as there was no motor traffic.

Girls, being in the majority, decided to form a society and Hashomer Hatzair were founded. We used to meet at the bridge with the Pumpian society of the same name, and uniforms were made over weekends. On the cultural side my mother started a library of Yiddish and Hebrew books, which were well used. The men of the shtetl made a living by going to the nearby Derfer to buy chickens, eggs, sheepskins and intestines. They cleaned the intestines, and these were in great demand in Germany for making Vienna sausages. Before Christmas, geese were much sought after, so we used to force-feed them and export them to Germany together with lots of dairy products. Germany was Lithuania's biggest trading partner in dairy products. But the main income was derived from drafts: nearly every household had a father or son in South Africa, or in the United States, who sent money in the form of drafts. These could not be changed in Pushelat as it had no banks so everyone had to go to Ponevezh where there was a Jewish bank (Elizur's). They also had to do shopping there, as Pushelat had no clothing, or shoe shops. In Ponevezh ice cream was a great attraction for us as it was not available in Pushelat.

The year 1925 in our shtetl was memorable for two events. The first one was a family affair - Ma's brother Joseph Witten (Viten) arrived unexpectedly from Jacksonville, Florida, where he had a big department store, to visit his mother and sisters. My mother's sister Soro-lta Berman was our next door neighbour. Uncle Joseph brought us lots of presents of clothing and shoes. To our great surprise and joy, Bobba recognised his voice as soon as he walked in and great was her joy. He stayed with us for two days and donated 50 dollars to the shul , which was a fortune in those days. It was used to repaint the shul in all the colours of the rainbow.

The second event - a national one - was the opening of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. A radio with a loudspeaker at full volume was installed in the open marketplace and all the Jews gathered there to enjoy the great historical event. We listened to the speakers, Dr Chaim Weitzman and Sir Herbert Samuel, even if none of us could understand English or even Hebrew.

My mother was quite well off by Pushelater standards. Father sent her a £10 draft every month, and when I got to South Africa I sent her a £4 draft, so with the exchange rate of 50 Lit to the pound she had plenty of money, more than she could spend in Pushelat. She paid no rent, no electricity or water accounts, and no income tax or insurance. There was a small municipal charge. We had a plot on the outskirts of the shtetl where we kept a cow and chickens. We had our own milk, eggs and butter, and grew our own potatoes and other vegetables. Herrings - the main diet - we bought by the barrel; they were cheap, and the Holland herrings, much in demand, were our staple food together with potatoes.

We baked our own bread and kitkes. The only thing we had to buy was meat - veal was very inexpensive - and we only bought red meat on Yomtov from the Kotons, the only kosher butchery. I was so sick of veal that when I arrived in South Africa I would not touch it for years. My mother was therefore safe and secure and did not want to leave Pushelat. It was only my father's pleas, along with mine and my brother Sam's, that made her change her mind. She just managed to arrive in South Africa as she was in one of the last ships to arrive in the country, with Jewish immigrants, before Jews from the Baltic were no longer allowed in.

When I finished at the primary school in Pushelat I begged my mother to let me study further in Ponevezh as I used to get good marks. I enrolled in the Ponevezher Yiddishe Mittel School, which had four classes. We wore very nice uniforms. In summer we used to walk home barefoot. In the winter lifts had to be arranged to and from Ponevezh and Pushelat. We had excellent teachers, notably a Wilkomirer poet Leib Bassman, and I received a very good education. I passed with flying colours and came second in the school.

I was just over sixteen, not knowing what to do in the future, when a registered letter arrived with visas for me to enter South Africa and enough money to pay for a train ticket to Kovno, then the capital city. There were more train tickets to Libau, Latvia, where I took a boat, the Baltriger to London. Together with my best friend in Pushelat, Hilel Peisa (Hilke) (Phillip) Koton, we boarded the ship “Garth Castle” and arrived in Cape Town, June 23, 1929, never to return to my Pushelat.

Arriving on the same ship with Willie and Hilke, also from Pushelat, were Jankel Sapira, Boruch Gurvic, Osif Davidzon, and David Zuk.

THE DEATH OF A SHTETL 1929 – 1941

From South Africa, we corresponded with Mother on a weekly basis. In one letter, Ma wrote about how Pushelat acquired a Rabbi after being without one for several decades. The Ponevezher Rabbi Kahaneman arrived in Pushelat one morning – his first visit ever – called the elders together, and asked them a favour. “There is a young Rabbi in Ponevezh with a wife and children who was conscripted into the army. The only way for him to get out is to get a job as a Rabbi.” He appealed to the community to help him out thus earning a big mitzvah and emphasised that it will only be a “paper” appointment, as he knew the community was poor and small in numbers. He thus had no intention of burdening them with a Rabbi. What could the elders do but agree with him for, after all, the Rabbi was one of the top Rabbis in Lithuania and head of the famous Ponevezher Yeshiva. The elders signed the papers for it and were happy to earn such a big mitzvah.

Several weeks later, on a bright morning, a large horse-drawn wagon arrived in Pushelat with Rabbi B.J. "Yossel" Pagremanski, his wife, Taube Berlin, three children, furniture, boxes, chickens, etc., ready to settle down as a Rabbi. The shtetl was in shock! How could the Ponevezher Rabbi play such a trick on them? The leaders of the shtetl approached the newly arrived Rabbi and expressed their concern. He smiled and replied, “God will provide.” To help pay the expenses for the new Rabbi the elders decided to give him a concession of the supply of yeast to the entire community. As every household baked their own bread, it was of some help. As the new Rabbi had said, “God will provide.”

The shtetl lived in peace. They got on well with the Lithuanians and there were no pogroms. The wives and children who had husbands and fathers in South Africa joined them as the Immigration Act luckily made provision for families to be re-united and the shtetl emptied. The remaining families kept on getting “drafts” from South Africa, as well as from relatives living in other countries, and the shtetl lived on. Happily, my mother and family decided to rejoin us in South Africa just in time before World War II broke out on September 1, 1939.

In 1940, Russia occupied Lithuania and it became a Soviet Socialist Republic. To appease the Lithuanians, Russia returned Vilna, and the Vilna District, to Lithuania and made Vilna once again the capital. The Poles, under General Zeligovksky, had captured it from the Lithuanians in 1918 and had refused to give it back. I remember how in every shtetl and city there were notices and/or statues saying, “We will never forget Vilna.” All relations and communication between Lithuania and Poland had been severed. You could not post letters nor telephone or travel to Poland and the teaching of Polish was forbidden. The Jews in the main were happy with the new situation as they believed it would safeguard their physical well being as the Soviet constitution guaranteed full equal rights to all its citizens irrespective of race or religion. Yiddish schools, newspapers and theatres soon appeared and flourished for a time and the universities were open to all. However, the rich Jews suffered as their businesses and factories were confiscated.

In Pushelat, a Soviet Council was proclaimed but with no enthusiasm from the Lithuanians. My cousin, Velvel Viten, was appointed Chairman of the Council (Mayor) of Pushelat. He was a Leftist as were most of the Jewish youth. Velvel was a self educated intellectual and a poet of note. I well remember how he used to read poetry to us, some of which was published in the Yiddishe newspaper. He was already married to Soske, the beautiful youngest daughter of Nochum-Bere Setzer. They had a baby. The first act of the new Soviet Council was to expropriate the vast estate of the “Gallach” (priest). It was divided among the poor peasants and Betzalel, the poor son-in-law of Bere Koton the butcher and they were the lucky ones. Betzalel had a big family, like most of the Jews, and some of his sons escaped the Holocaust by joining the Red Army. The Jews in Pushelat got used to the new situation.

This uneasy but history-making period only lasted a year for, on the 22 nd of June 1941, the Germans attacked Russia without warning. Within days the Red Army began to withdraw from Lithuania and the Germans advanced throughout the country. The Lithuanians did not wait for the Germans to arrive. The “Siauliste” (Lithuania Voluntary Militia) started rounding up Jews and Russians and the first victims were the municipal council. Velvel and his family were the first to be shot. Some of the Jews were rounded up and taken to a thick forest on the road to Janishkel about 1 ½ kms away. In a clearing, they were shot and buried in a mass grave. Twenty Jews hid in the small building at the entrance to the Jewish cemetery normally used to prepare the bodies for burial. They were soon discovered and all were shot to death.

When my good friend Howard Margol, in Atlanta, Georgia, questioned some of the Lithuanian elders on one of his visits to Pushelat in recent years, he was given vivid descriptions of how the Jews were murdered there. He was told how the “Lithuanian bandits” grabbed the small Jewish children by their ankles, swung their bodies around, and smashed their heads against a wall or tree. The shtetl had only one doctor, a Jew by the name of Joseph Shapiro. One of the Lithuanian women offered to convert Dr. Shapiro to Catholicism and marry him but to no avail. As Doctor Shapiro tried to attend to the wounded, he was brutally murdered. It is not known exactly how many Jews were murdered in Pushelat by the so-called “Lithuanian bandits.” The Germans forced the remaining Jews into the ghetto in Ponevezh. In September, 1941 all of the Jews in the ghetto were herded into the nearby Pajnoste Forest and murdered there.

Of all the Jews who were living in Pushelat on the 22 nd of June 1941, only one man escaped. After the war, he lived in Kaunas until he died in 1992. His son, Janush Boris, still lives in Kaunas. Pushelat is still there today but, as a shtetl, it no longer exists.

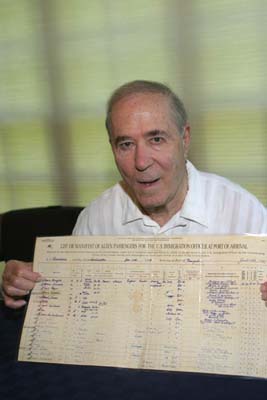

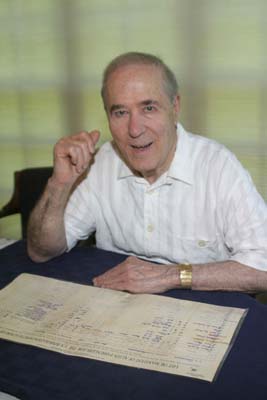

Howard Margol, a native and former resident of Jacksonville, Florida is Past President of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. His father was born and grew up in Pushelat. In the 1920-1930's, thirty Jewish families from Pushalot lived in Jacksonville, Florida.