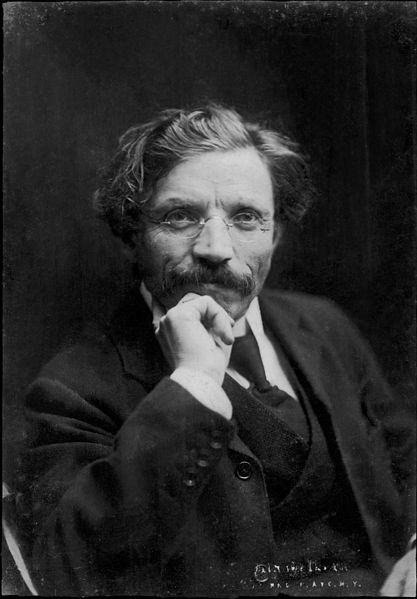

Sholem Aleichem (1859 - 1916)

By Isabelle Nemirovski

Sholem Aleichem

Source: www.wikipedia.org

Sholem Aleichem

1 - real name Sholem Rabinovitch - was born in 1859 in Pereyaslav near Kiev (Ukraine). He successively works as tutor, rabbi of State, banker, stock and insurance broker, and publisher.

Author of numerous short stories, children's stories, novels and plays, he is recognized as one of the "three founding fathers" of modern Yiddish literature together with Mendele Moikher Sforim and Yitshok Leybush Peretz.

Ardent defender of the Jews of the ghetto, the "ordinary people," he begins writing at the age of seventeen, but it is in 1883 that he makes his debut as a writer in Yiddish on the columns of the Yidishe Folksblat (Popular Yiddish Sheet). Afterwards he spends part of his fortune, which he acquired by his marriage to promote the great Yiddish writers.

In 1887 he moves to Kiev where he produces more stories, mainly about childhood, and novels, including Sender Blank, Yossele Solovey, and Stempanyu. In 1888–89, he put out two issues of an almanac, Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek ("The Yiddish Popular Library") which gave important exposure to young Yiddish writers. He was famous, but writing did not pay, and he supported his family as a trader on the stock exchange. In 1890, after losing his money, he moves to Odessa, then back to Kiev in 1893.

It’s in Odessa that he writes his book “The Adventures of Menahem-Mendl”, acclaimed by literary critics that said that he is the "Jewish Mark Twain" or "Jewish Anton Chekhov." This work is, in fact, together with “Tevye the Milkman”, one of the masterpieces of the author. In the form of an exchange of letters between Menahem Mendl-- who temporarily leaves his native shtetl to Kiev and Odessa in the naive hope of making a fortune - and his wife, the author recounts the misadventures and repeated failures of this unrepentant dreamer. Under an ironic but always benevolent pen – the writing style of Sholem Aleichem is an important element of comedy in his work - he describes how this character, full of provincialism, faces the modern world struggling every moment between admiration, consternation and incomprehension. Menahem Mendl, wrote to his wife that while the city is very beautiful and we can do great business, he feels a foreigner because it is filled with ungodly. The Jews of Odessa deserted the synagogues and pray whenever they want, often wearing top hat and without fervor. He even wondered if they would not have lost their soul!

Commemorative plaque on the wall of Sholem Aleichem's house in Odessa.

Source: Private collection

Sholem Aleichem is also involved during his short stay in Odessa, in the publication of the journal Yevreskaya Biblioteka (The Jewish Public Library). His popularity is immense and, although he only lived three years in the city, he is considered as a "native son." A commemorative plaque is now visible on the wall of the house in which he lived.

In 1905, due to a wave of pogroms that swept through Odessa and its surroundings, Sholem Aleichem leaves Russia. He first lives in Switzerland with his family then emigrates to the United States during the First World War.

Exhausted by the lecture tours that forces his precarious financial situation; he dies in New York in 1916.

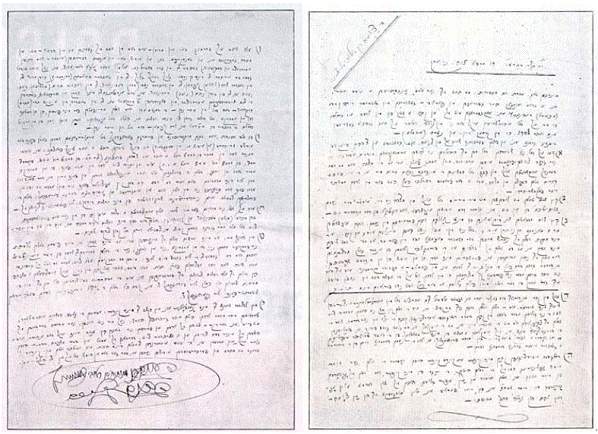

Tenderness is one of the fundamental qualities of Sholem Aleichem. It seems endless for his fellow human beings, for his fictional characters and for the members of his family. It is particularly noticeable in the expression of his will that he wrote on Sept. 15, 1915, in New York, after the death of his son Mikhail.

Last Will and Testament of Sholem Aleichem (September 19, 1915)

Last Will and Testament of Sholem Aleichem (September 19, 1915)

“Today, the day after the Day of Atonement, with a new year just begun, a great tragedy occurred in my family: my elder son, Misha (Michail) Rabinovich, passed away, and a part of my life was carried to the grave. Therefore I decided to redo my will, which I had written in 1908, in Nervi (Italy), when I was ill.

Now enjoying good health and being in full possession of my mental faculties, I am writing my will, which consists of ten items:

1.- Wherever I may die, let me be buried not among the rich and famous, but among plain Jewish people, the workers, the common folk, so that my tombstone may honor the simple graves around me, and the simple graves honor mine, even as the plain people honored their folk writer during his lifetime.

2.- Let my monument contain no titles of any kind,…, and bear only the name “Sholem Aleichem” on one side and the following inscription in Yiddish on the other. (epitaph).

3.- Let there be no arguments or debates among my colleagues who may wish to memorialize me by erecting a monument in New York… For me the best monument would be for my works to be read and for there to be, among the wealthy classes of our people, patrons who wish to publish and disseminate them, both in Yiddish and in other languages, thereby giving to the people an opportunity to read them, and to my family a worthy existence…

4.- Let my son, now my only son, and my sons-in-law, provided they wish, recite kaddish at my burial, then during the first year and thereafter on the anniversaries of my death. And if they are unwilling to do so, or time does not permit it, or if it goes against their religious convictions, they can consider this request fulfilled if they join together with my children and my grandchildren, and with good friends, and read this will, and select one of my stories, one of the really joyous ones, and read it aloud, in whatever language they understand best…

5.- My children and my grandchildren may hold whatever religious beliefs they wish. But I ask them to maintain their Jewish origin…

6.- All I possess, both in terms of cash–if I have any—and in terms of books, printed matter, or manuscripts, whether in Yiddish or in other languages (except those translated into Hebrew), belong to my wife Hodel daughter of Elimelech, or Olga Rabinovich, and after her death they will pass to my children in equal shares… As for my works in Hebrew, they belong to their masterly translator, my son-in-law I. D. Berkovich, and to his daughter, my granddaughter Tamer (Tamara) Berkovich. It will be her dowry.

Of the royalties that are due me for my plays… half is to be given to my heirs and the other half set aside in the name of my granddaughter Bela, the daughter of Michail and Sore Koifman, to serve as her dowry.

7.- Of the monies obtained, 5% or 10% is to be deducted for the Jewish Writers’ Foundation (Yiddish and Hebrew)… or distributed among needy writers.

8.- If I do not manage during my life to erect a monument over the grave of my son Michail (Misha) Rabinovich, who recently passed away in Copenhagen, let my heirs do so with a generous hand, and let them say kaddish every year on the anniversary of my death and distribute charity to the poor and needy.

9.- My wish is that my heirs should arrange that my books and my works will never be sold, neither in North America nor in Europe, and that their yield will be sufficient to live during all the years fixed by the laws of each country…

10.- My last wish for my successors and my prayer for my children: Take good care of your mother, beautify her old age,… Do not weep for me, on the contrary, remember me with joy; and the main thing, live together in peace, …think of other members of the family, pity the poor, and… pay my debts, if there be any.

My children: Bear with honor my hard-earned Jewish name, and may G-d in Heaven sustain you ever, Amen.

Notes:

1) Sholem Aleichem in Yiddish means "Peace be upon you!" and it's a traditional greeting.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCES

- www.morim-madrishim.org

- Cholem Aleichem, Menahem-Mendl, le rêveur, Paris, Rivages, 1993

- Nathan Weinstock, Le Yiddish tel qu’on l’oublie, Regards sur une culture engloutie, Paris, Metropolis, 2004

- wikipedia.org

Isabelle Nemirovski (June 4th, 2012)