-

Home

Home About Network

- History

Nostalgia and Memory The Polish Period I The Russian Period I WWI Interwar Poland WWII | Shoah 1944 Memorial Commemoration- People

Famous Descendants Families from Mlynov Migration of a Shtetl Ancestors By Birthdates- Memories

Interviews Memories 1935 Home Movie in Mlynov 1944 Memorial Commemoration Commemoration Wall- Other Resources

Mlynov and Mervits in the WWI Period And Its Aftermath

Contents

Flip-flopping Nationalities | The Great War, Revolution, Civil War and Its Aftermath | Mlynov and Mervits in the War Period (1914–1917) | The Eastern Front During WWI | The Diary of Yitzhak Lamdan | Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive in 1915 | Helen Lederer recalls the evacuation of Mlynov | Mlynov in the Brusilov Counter Offensive of 1916, 1917 Russian Revolution / The US Enters the War | The War As Seen By Mlynov Immigrants in Baltimore | The Bolshevik Revolution and the Family Bar Mitzvah | Brest Litovsk Treaty and The Russian Civil War | Aftermath of War | The Fishman Family | The Shulman Family Migration | The Mlynov Boys in Buenos Aires | The Path Through Mexico

***

Flip-flopping Nationalities (1914–1922)

Perhaps the best way to summarize this period of time is with the classically ironic Jewish joke told to me by, Gene Fax, the great-grandson of Getzel and Ida (Rivitz) Fax, the first pioneers to Baltimore. I had tracked down Gene in an effort to learn more about the first couple who had left Mlynov for Baltimore. He was explaining to me that Getzel’s birthplace, which was close to Mlynov in Demydivka, had changed hands between Russia and Poland a number of times:

Old Yiddish joke: “Mama, Mama, they signed a treaty and we're no longer part of Poland, we're part of Russia!"

"Thanks God, anather Polish vinter vould have killd me."The joke is ironic in several ways, though the layer of ironies deepen as you think more about it. The notion that a change in nationality would affect the coldness of the winter is obviously ridiculous, at least when taken literally. But at a metaphoric level, winter also represents "the climate" under a nationality and the wish that Russian rule might not be as cold as Polish rule, a hope that may have been nursed during this period when Mlynov and Mervits changed hands multiple times. Perhaps the joke's ultimate sad and deep irony is that winter under Russia Bolshevik reign would not in fact be better, though things could get worse and, of course, eventually did.

In the period at hand, from the outbreak of WWI in 1914 until 1922, the small villages of Mlynov and Mervits were near the center of the drama, as borders and control shifted during the War, and the civil war that followed, with the result that these villages moved back and forth between different national identities. It is to the details of this period that we now turn and what we know about Mlynov and Mervits inhabitants during the war and its aftermath.

Jump back to the top.

***

A Tumultous Time: The Great War, Revolution, Civil War and Its Aftermath

The period from 1914–1922 was a tumultuous one for the world and, at times in this period, the small villages of Mlynov and Mervits were literally in the heart of that turmoil. This was the period of WWI (1914–1917), a Russian Revolution (Feb.–Mar. 1917), the US entrance into the War (April 1917), followed by the Bolshevik takeover (Nov. 1917), followed by Russian Civil War (1919–1922), a Russo-Polish War (1919–1920), the beginning and end of Ukraine as an independent nation, and a series of brutal pogroms (1919). It was a time of hope and despair, separation and anxiety, loss and destruction, which ended in the tiny villages of Mlynov and Mervits belonging once again to Poland. It is hard to imagine what the period must have felt like for those who lived through it. A number of those who lived in these villages before the war returned home, but not all did. In the wake of the War, a third wave of immigration to Baltimore and the US took place, along with an emerging emigration to Palestine, in part because the US had tightened its immigration policies and in part because Zionism had reached the villages and had started to stir the passions of those living there through the experiences of war, dislocation and the Balfour Declaration.

We have several short fragmented reflections from Mlynov and Mervits villagers from this period, though not all have been translated yet. Most of what we know is from after the War, as the families coped with the consequences of the War. We know that some families were separated across the ocean, that the village of Mlynov was evacuated, to Novohrad-Volyns’kyi according to oral traditions,[1] and that some homes were destroyed and some lives lost. The Eastern Front during the War moved back and forth particularly close to Mlynov and Mervits during the Battle of Galicia, the Gorlice Tarnow Offensive, and the Brusilov Counter Offensive. By the time the Bolsheviks finally signed a separate treaty with Germany, the Germans and Austrians had pushed across Ukraine well past Mlynov, all the way to Bedichev and Gomel, putting fear in the Bolsheviks that they would reach Petrograd. The Civil War that followed the end of WWI was complex, multi-ethnic and multi-national, with the boundaries of national entities shifting back and forth until their stabilization in 1922. We have several hints about how the the inhabitants of Mlynov and Mervits fared during this period from stories they wrote down or told their descendants and based on what they did after the War. In many ways, we have to imagine the details of what their lives were like from the fragments of stories they left behind, and by attempting to see how the macro trends of the period may or may not have touched the tiny villages of Mlynov and Mervits.

***

When the War first broke out, Mendel Teitelman and his friend, Simha Zutelman, were evacuated from a Yeshiva where they were studying when the Germans approached and were put into forced labor gangs during the War. When Mendl returned home after the War he learned that his brother drowned in the interim and the village of Mervits had been destroyed.[2] Through the eyes of herself as a young woman, Helen Lederer recounts the difficult and confusing experience of evacuation from Mlynov, as her mother and another pregnant woman tried to find food and a place where they could be safe among many refugees who were in the same situation. Helen and her family left for America after the War.[3]

Out of the experience of trauma, another Mlynov boy, Yitzhak Lamdan, eventually headed to Palestine and eventually wrote a poem, called "Masada," that would speak for a generation of Zionists and that would despair of Jews finding a meaningful life in the Diaspora. During this period, Yitzhak had been uprooted and wandered through Southern Russia with his brother before joining the Red Army. He lost his brother during the war, and his family home was destroyed during this time. Given his trauma, it made perfect sense that Yitzhak came to the conclusions he did. According to one source, Yitzhak was the first person from Mlynov to emigrate to Palestine in 1920.[4] Yitzhak would return to visit the village in the 1930s, after he had written his famous poem, and his presence in Mlynov was captured in a photo in the Mlynov-Muravica Memorial book. He was not the only one from Mlynov to return during this period, as we shall see.

There are thus two ways to approach the experiences of the Mlynov and Mervits residents during the War. One can read first about the battles on the Eastern Front that came close to the villages and imagine the experiences of the villagers, or one can jump to decisions they made in the aftermath of the War, which reflect their actual reactions to their War experiences. Either way, what emerges is what could only have been a traumatic experience, one which reshaped the lives of those who came back to the villages or left for good in the wake of the War.

Jump back to the top.

Mlynov and Mervits in the War Period (1914–1917)

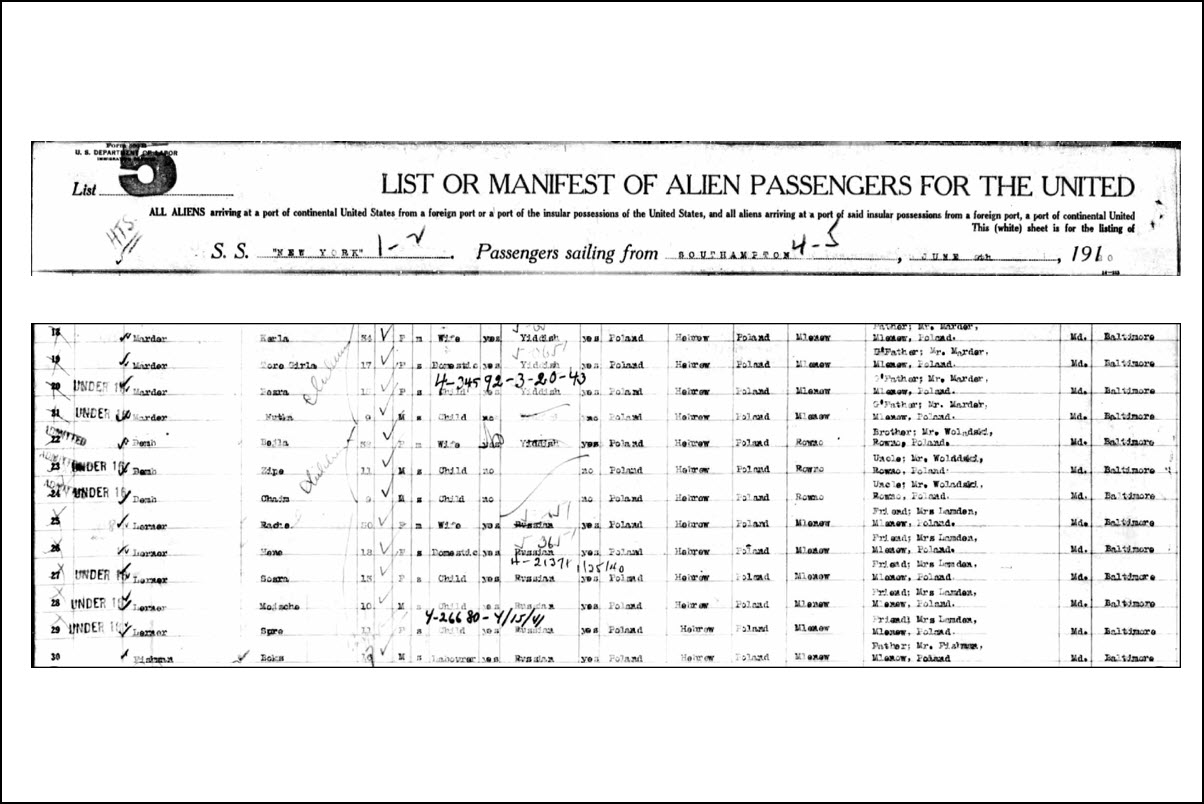

Between 1910–1914, a second large wave of Mlynov families (of at least 28 individuals) had already left the village and migrated to Baltimore to join relatives and friends, which now had, for all intents and purposes, a "little Mlynov" there. In a number of cases, husbands had gone on in advance of their families with the expectation that they would soon bring their families to join them. That was not to be.

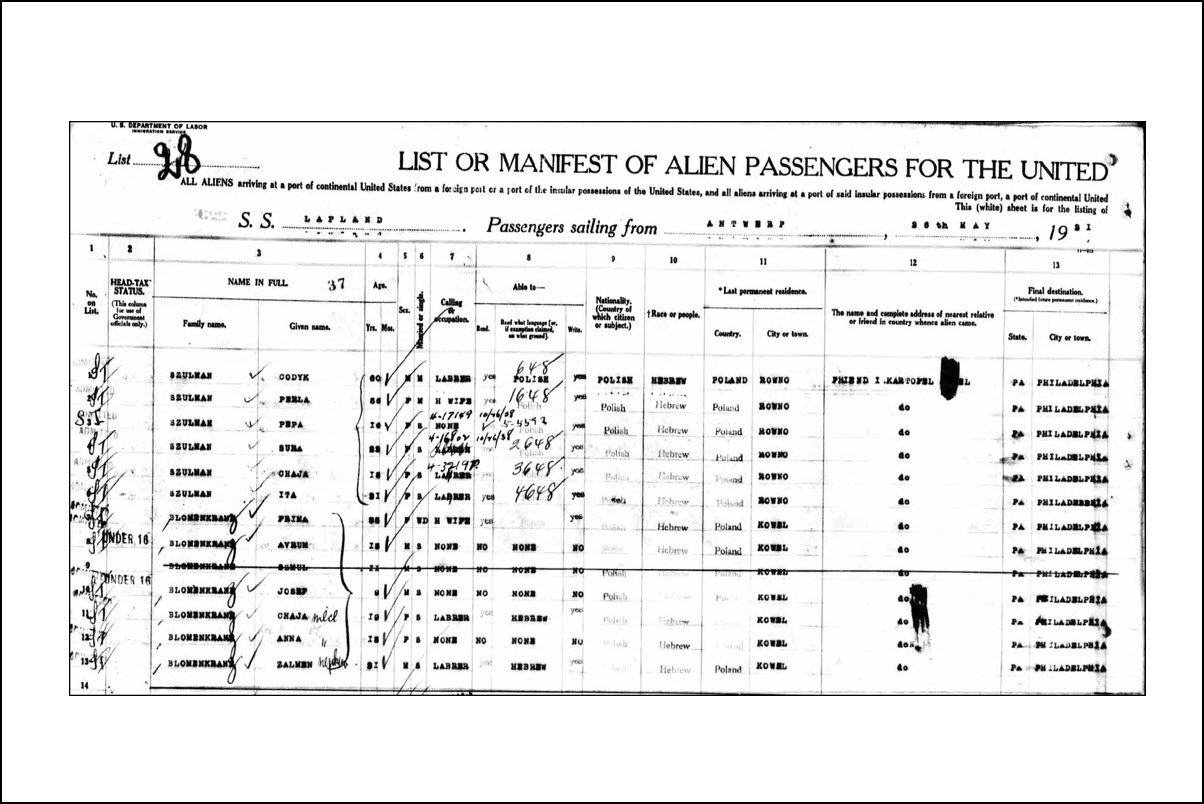

When WWI broke out in 1914, a number of Mlynov families were thus separated across the ocean. Husbands were in Baltimore and their wives and children were still back in Mlynov. Immigration all but stopped and in a number of cases, husbands wouldn't be reunited again with their wives and children for six years or longer. Aaron Demb, as one example, had left Mlynov and arrived in Baltimore in March 1914, just months before the War broke out. He wouldn't see his wife Bejla Demb and his sons for six years until 1920, after the war had ended and immigration had opened up again.

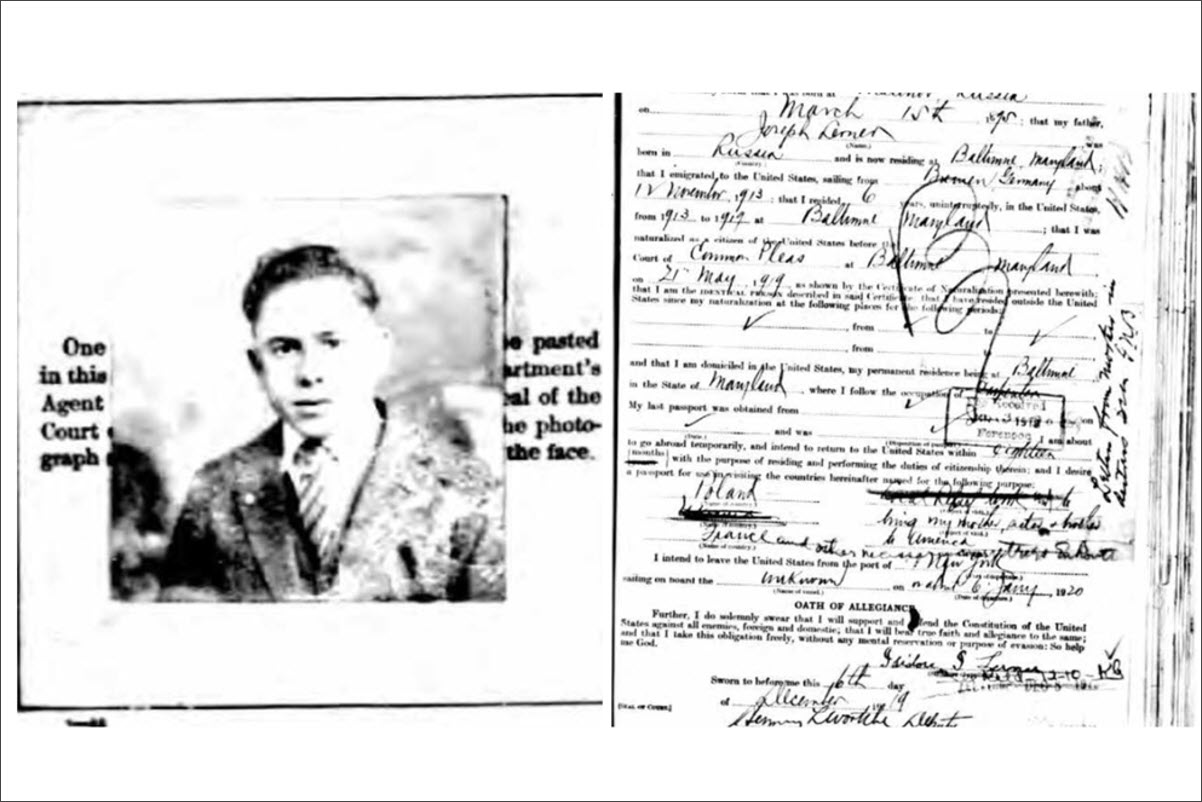

Other husbands who were separated from families in Mlynov had come even earlier including Isaac Marder, Joseph Lerner, Nathan Fishman, and Nathan Gruber, among others. A visible manifestation of this separation was the large gap in birthdates between some of the families' children. Nathan and Gertrude (Gitla) Gruber, for example, had their second child, Dora in 1911 in Mlynov. They were then separated by the war. Gertude didn't rejoin her husband until 1920. They then had a daughter, Sylvia, one year later in 1921, ten years after their second child.

The separation of these Mlynov husbands from their wives and children was probably the most painful of the separations produced by the War, though all of the Mlynov immigrants to Baltimore and elsewhere in the US had siblings and in many cases parents still back in Mlynov. Three of the Demb sisters, for example, were already in Baltimore, while their parents and three other siblings were still back in Mlynov. Similarly, two of the Goldsekers had arrived by this time in Baltimore, but their father and several of their siblings were still in Mlynov.

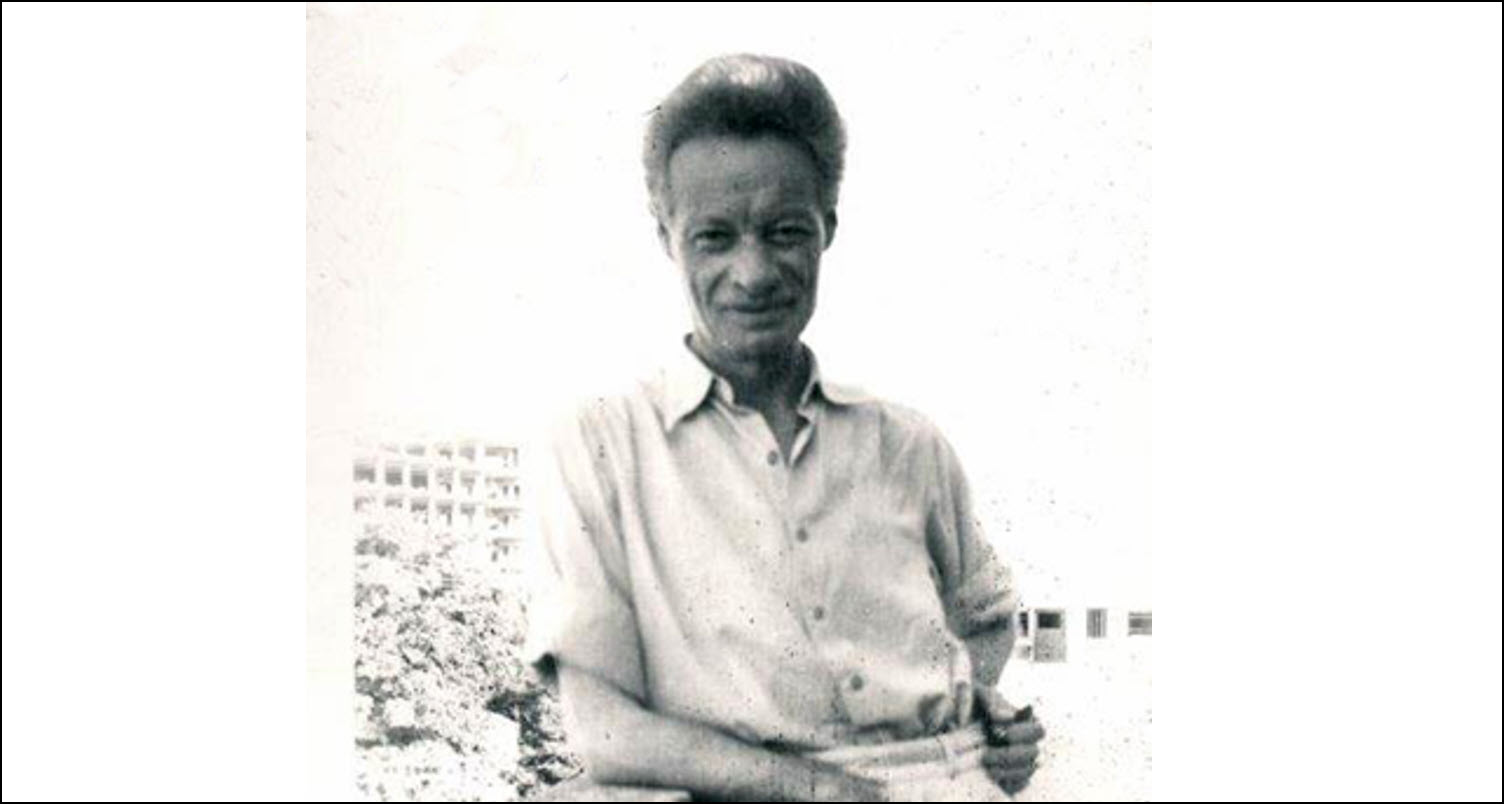

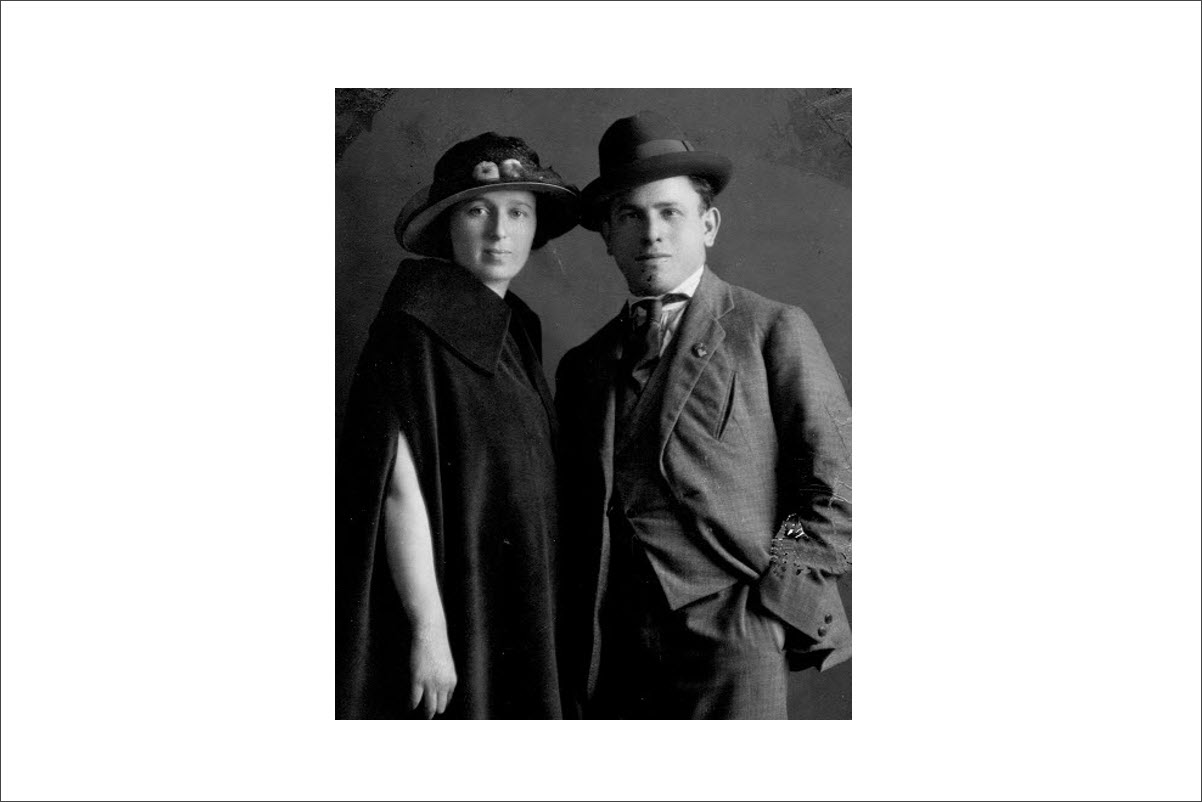

Mlynov husbands stranded in Baltimore with their families back in Mlynov during the war years. Joseph Lerner, Nathan Fishman, Aaron Demb.[5] Courtesy of Marvin Demb, Fredda Lerner, and collage from Howard Schwartz

Mlynov husbands stranded in Baltimore with their families back in Mlynov during the war years. Joseph Lerner, Nathan Fishman, Aaron Demb.[5] Courtesy of Marvin Demb, Fredda Lerner, and collage from Howard Schwartz

The story of this period is thus a tale of two cities: On the one side of the ocean, Mlynov immigrants to Baltimore were left worrying about what was happening to loved ones back in the village in Russia and what the War meant for them as new immigrants to America. For much of the period they may have had little news of family back in the War zone, and articles about the War and the Eastern Front in particular, showed that fighting was moving back and forth near Mlynov. Those still living in the shtel had to face the threats and fallout of war and the uncertainty if they would ever see their loved ones again or what would happen to the village they loved. There were many uncertainties during the war and Mlynov was literally at the center of them.

We have only a few first hand accounts and oral traditions by Mlynov and Mervits descendants from this period, though this period has receded from memory under the weight of the next war which would be so much more devastating. One can only imagine that the unknowns during this period must have been terrifying for the Mlynov families which were split in two and uncertain of their future. It probably helped, to start with, that the United States remained neutral from 1914–1917, though one wonders whether the Mlynov villagers or the Mlynov immigrants favored Russia or the central powers of Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire.

Would life, as it had been under Russia, pogroms and all, been preferable to life under Germany or Austria-Hungary? Austria-Hungary in fact advertised to Jewish communities suggesting that if they won the war, the Jews of Russia would finally achieve equal rights; We know that the question of preference was not a simple one for Jews as evident in the split that emerged within the worldwide Zionist organization that attempted to keep neutrality but in practice had factions emerging that favored one or the other victors as better for the Jews.[6] Perhaps the residents of Mlynov hung out on market days and debated the merits of Russia winning or losing the war. Perhaps some of them anticipated just how costly and difficult it would be for them and their families. On the other side of the ocean, in Baltimore, German speaking Jews had arrived before their Russian counterparts and the Jewish community itself, while officially staying neutral, had divided loyalties for the first part of the war.

Mendel Teitelman, for example, recalls how the outbreak of the war impacted him and one of his friends while they were studying in Yeshiva in the town of Baranovitch. He writes:

In the beginning of the First World War in 1914, I was a student in the Yeshiva (religious school) in Baranovitch. Although I was very young, I learned before [i.e., already studied] in the Yeshiva of Ruvuo and in Stolpts [today, Rivne, Ukraine and Stolpe, Belarus, near Minsk]. I always remember with love the wonderful two years I spent in Ruvuo and Stolpts. My parents of blessed memory were pretty well off; nevertheless I "ate days" [i.e., got free meals as was customary for students] in the houses of the landord of the city according to the order of the Trisker Rabbi.

I was in Baranovitch when the Germans of Kaiser Wilhelm entered the city. The Russian front was not far from Baranovitch and because of the security reasons and because of the danger of spies, a part of the population was evacuated deep into Poland which was already occupied by the German army. Among those misfortunate people I was with my friend Simcha Zatelman [Zutelman]. January 1, 1916 we arrived half frozen in Ostrov-Mazovetski near Warsaw and were placed in army barracks in Kamaraove near Ostrov. Due to the lack of food, a typhus epidemic spread among the people. The situation lasted about six months. We were divided in groups of fifteen people and each group was assigned to a nobleman (rich owner of fields, forests, and many servants). The nobleman [we worked for] gave us all kinds of hard work and very little to eat. We did not despair; we hoped that freedom would come and we would return to our houses and parents. This situation lasted until the Russian Revolution in 1918. We decided [at that point] to return home. The journey was long and dangerous. At first we were in our little town Mervits which had only three Jewish houses left after the war.[7]

Jump back to the top.

***

The Eastern Front During WWI

When WWI started, the concentration of fighting was initially on the Western front, which Germany had opened by invading Luxembourg and Belgium. German leaders understood that eventually they would have to deal with Russia and the Eastern front, but the strategy was to win quickly against France on one front and then turn attention to the East. The strategy, however, did not work as planned and after some intial successes in the West, the Western Front became a stalemate involving trench warfare that didn't change much for the duration of the war.

***

The Battle of Galicia (Lemberg) Not So Far from Mlynov and Mervits

The "Battle of Galicia," also called the "Battle of Lemberg" was the first major battle between Russia and Autria-Hungary that took place in August-September 1914, shortly after the War began. The front was near Lemberg or “Lviv” which is a drive of 2.5 hours west of Mlynov today. Russian forces must have been passing by Mlynov on their way to the front during the early stages of the war. The Austro-Hungarian armies were severely defeated, losing upwards of 324,000 men, and were forced out of Galicia, while the Russians captured Lemberg and, for approximately nine months, ruled Eastern Galicia.[8]

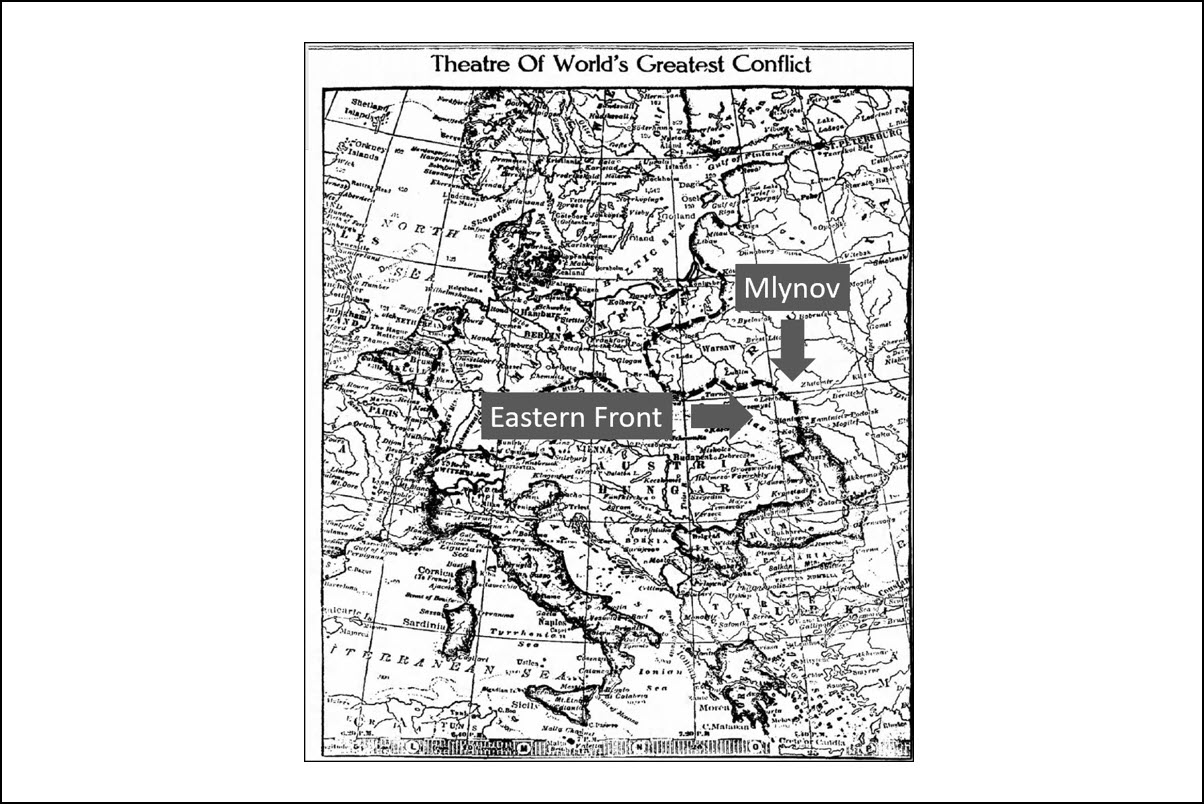

In the map, you can see where the fighting occurred along the Eastern Front from August through September, 1914, during the Battle of Galicia. A large arrow pointing to Mlynov on the right side of the map illustrates how close the battles were to the towns during this period.

We can imagine that residents of Mlynov and Mervits, and their relatives in Baltimore, breathed a sign of relief that the War did not overrun the villages at this time, even though there was probably no love lost for the Tsarist regime. Austro-Hungary had, in fact, attempted to build Jewish sympathy for the Central Powers by reminding Jews of their long standing suffering under Russia rule. For example, in this article, which appeared in the Baltimore Sun on Sept. 10, 1914 (p. 1), Austria issued the following appeal to the Jews of Poland:

Our flags bring justice, freedom and equal rights as citizens, religious freedom and freedom to live undisturbed in economic and cultural life. Too long you have lived under the yoke of Moscow. We come as friends...A new era begins for Poland. We will use all our strength to put it on a sure foundation of equal rights for the Jews.

Across the Atlantic, in Baltimore, the Mlynov and Mervits husbands, must have been worried sick intially about their wives and children near the war zone. Thank God the US was initially neutral in the war and they must have breathed a sign of relief when Russia routed the Austria-Hungarian armies.

One suspects that husbands and other relatives in Baltimore were following the War closely. A map showing the theatre of conflict was printed in the Baltimore Sun on Aug. 3, 1914 (p. 2) and suggests how emotionally difficult it must have been for the Mlynov immigrants to Baltimore to watch the War from across the ocean. Mlynov’s location is highlighted between Zhitomyr and Lemberg which are labelled on the map. The dark broken line represents the Eastern front which was very close to Mlynov.

Jump back to the top.

***

Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive in 1915

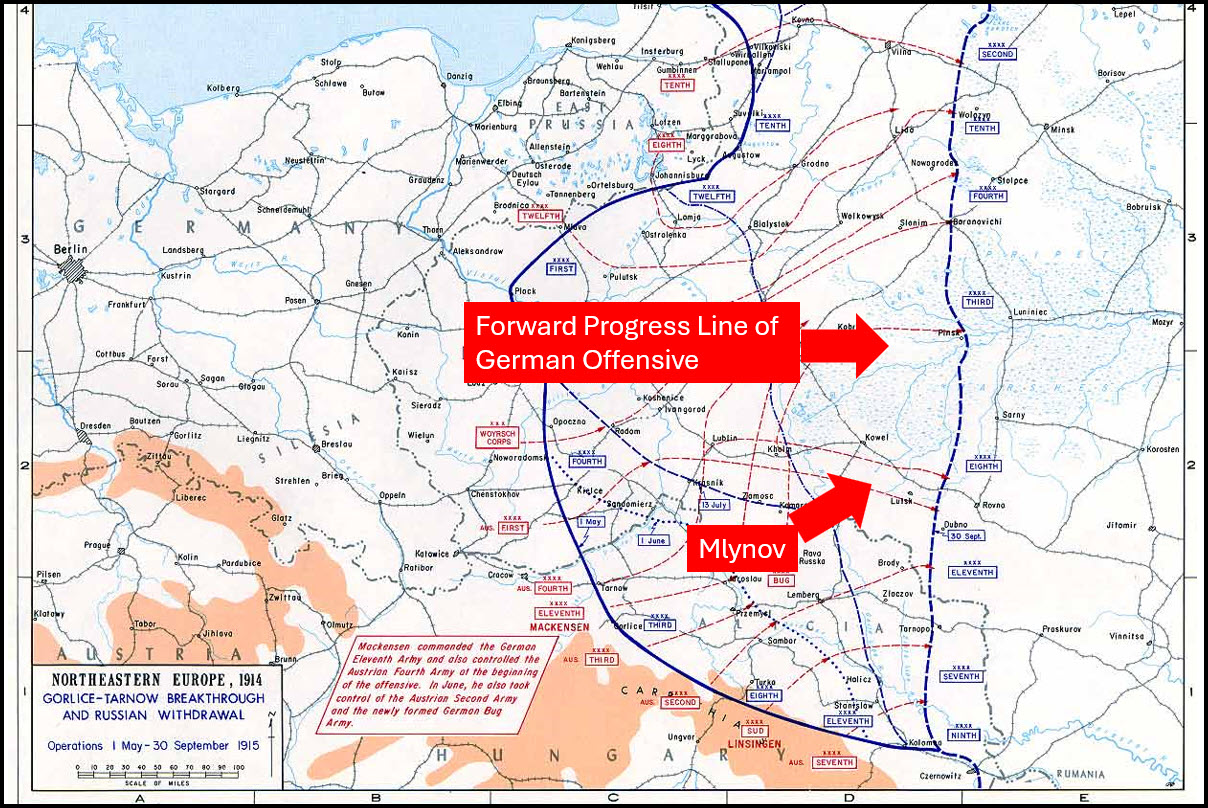

Mlynov in relationship to the Gorlice Tarnow Breakthrough. In the public domain[9]

Mlynov in relationship to the Gorlice Tarnow Breakthrough. In the public domain[9]If 1914 seemed to suggest that the inhabitants of Mlynov and Mervits might be safe from war, matters changed in 1915. At the start of the War, the German plan had been to strike a rapid and fatal blow against France and then turn attention to Russia, which would mobilize more slowly. While the Germans rapidly overcame Belgium in their drive to Paris, the French line held in the Battle of Marne. At that point, the war deteriorated into a stalemate as both sides dug in, and trenches soon stretched from the English Channel to the Swiss border. As one writer noted, “For the next four years, both sides essentially remained in position; neither machine guns nor heavy artillery, neither poison gas nor armored vehicles could provide the breakthroughs everyone expected.”[9]

In 1915, the German command decided to turn its main effort to the Eastern Front, and accordingly transferred considerable forces there. To eliminate the Russian threat, the Central Powers of Austro-Hungary and Germany began the campaign season of 1915 with the successful Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive in Galicia in May 1915.

The Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive during World War I was initially conceived as a minor German offensive to relieve Russian pressure on the Austro-Hungarians…on the Eastern Front, but resulted in the Central Powers' chief offensive effort of 1915, causing the total collapse of the Russian lines and their retreat far into Russia. The continued series of actions lasted the majority of the campaigning season for 1915, starting in early May and only ending due to bad weather in October.

During this time, the German and Austro-Hungarian armies were on the advance, dealing the Russians heavy casualties in Galicia and in Poland, forcing it to retreat. According to one account, the palace and park of the Prince Chodkiewicz were in hands of Austrian troops, while the settlement itself was held by Russian troops.[10]

Oral tradition among the Baltimore Mlynov descendants suggests families were evacuated from Mlynov and Mervits to Novohrad-Volyns’kyi, which was 160 km east (2 hrs. driving today). My guess is that this happened during the 1915 Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive. This seems consistent with the reflection in the Memorial book, by Aaron Harari from Merhavia in Israel. Harari recalls that “During World War I many people left Mlinov and became refugees in order to escape the heavy fighting. After the war, they returned and tried to establish themselves again.”[11]

Helen Lederer recalls the evacuation of Mlynov during WWI. She writes:

It happened in the time of the First World War. A cold winter day, a burning frost, a deep snow. The Germans approaching our town, Melinov. The soldiers packed us like sardines into the synagogue after they had driven us from our homes. We tremble from fear not knowing what to expect and what is our destiny. It is 2:00 o’clock in the night. Outside [it] is very cold and windy. The soldiers with rifles in their hands command us to go out in the street. Here we see a row of wagons. The order is, “Pack what you can on the wagons and you will follow by foot.

Women and children walk in the deep snow. We are going in the direction of Varkevetch [possibly the town called Verkhivs'k, Ukraine today, which was on the road to Rovno, 36Km away from Mlynov]. My mother with four little children, my aunt Sorke Pese Chulies and her little daughter, Devorele, continue walking. Suddenly the little Dvorele got lost. Mother ran back to find her child, the soldiers don’t let her run back, saying that the Austrian soldiers are [close] behind. Mother goes back and thank God she finds her child in snow exhausted.

In the morning we came to the town Varkevitch. We went to the house of my relative, Nachman-Leyb. The house if filled with refugees. There are my grandfather, Leybish Gershuus, his two daughters, Chane-Gitl and Chaya. There is no place for us. What to do and where to go? We open a little door that leads us to the basement where we spent the night, tired and hungry.

The second day we walked in the direction of the town, Azian [town unidentified]. In Aziran we were told that we must continue our trip by walking to the city of Rovuo. We came to Rovuo [possibly Rovno], but there was not any place for more people. The city was packed with refugees. My mother and the children and Batya-Chaya Malkes, a pregnant woman, we are all standing in the bitter frost, not knowing where to find a shelter. But here comes a gentile, a coachman, a warm human being, speaks Yiddish and takes us all to his house where we could rest.

The next day we went outside and we found out that this was a joint committee from America which distributes packages of food to everyone. My mother received a package and thank God, we have something to each. Meanwhile, Batya-Chaya Malkes gave birth to a child. The noble coachman kept us in his house for four months.

I will never forget this noble, wonderful man. The Austrians deferred [editor: retreated?] and most of our people returned to Melinov. I remained a certain time with my cousin, Gitl Sativer, and went with him to the same school. Mother wanted me home. We went through many difficult days and months and at the end we came to America. May it be the will of God that the future generation should enjoy better life and peace should reign all over the world. Amen![12]

By September of 1915, Russia troops were strategically withdrawing from what military terminology calls the Galicia-Poland "salient," a military term that designates a battlefield feature that projects into an opponent's territory and is surrounded on three sides, making the troops occupying the salient vulnerable. The Russian withdrawal during this time is known as the "Great Retreat."

By the end of 1915, two million Russian troops had been lost, half of them prisoners. For their part, the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary lost a total of nearly one-million soldiers themselves. The new frontline ran from the Baltic sea to the Romanian border. The new line was roughly on the line of Pinsk-Dubno-Ternopil, and ran close to, if not right through, Mlynov.

Jump back to the top.

***

Mlynov in the Brusilov Counter Offensive of 1916

When reading the various accounts of WWI, one has to infer for the most part where Mlynov and Mervits were with respect to the fighting on the Eastern Front. But in the 1916 Russian counter offensive, known as the “Brusilov Offensive” or the “June Advance,” Mlynov is at the heart of the fighting and is actually mentioned in Baltimore and other US newspapers for the first time.

The Brusilov Offensive in 1916. In the public domain[8].

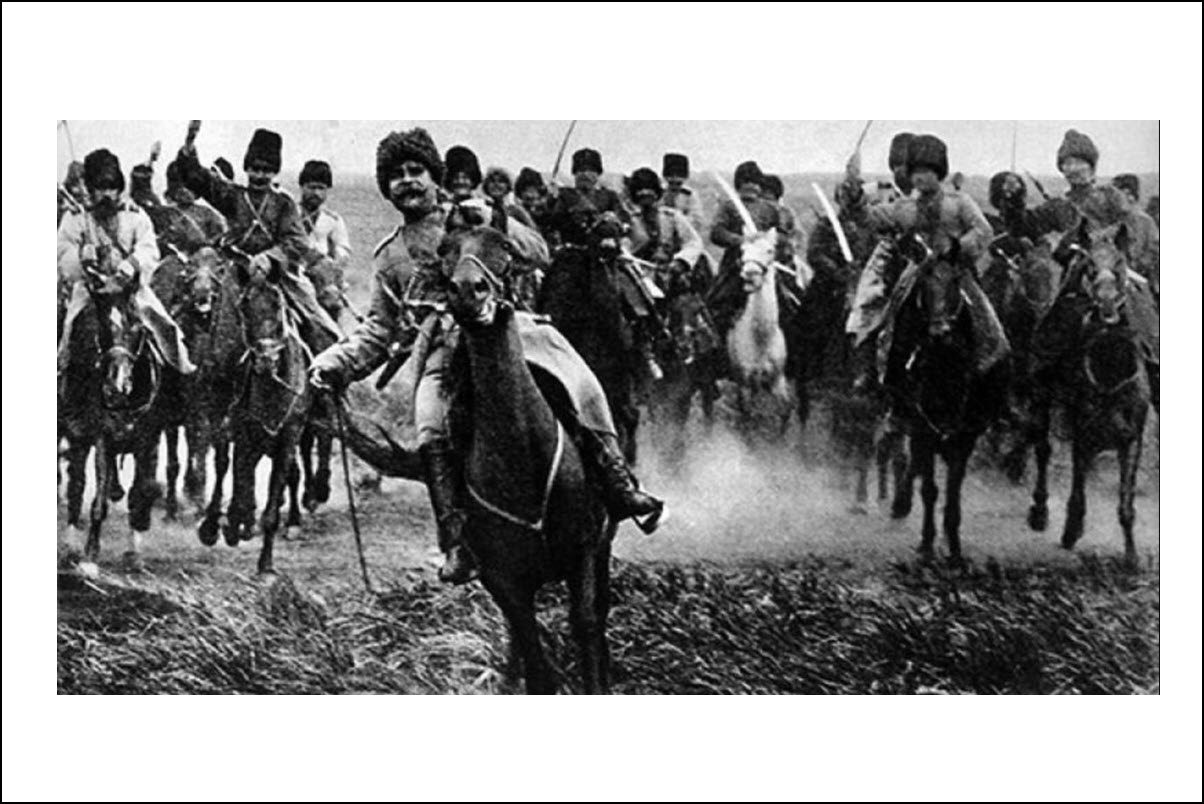

The Brusilov Offensive in 1916. In the public domain[8]. A photo from the Brusilov Offensive. In the public domain[8].

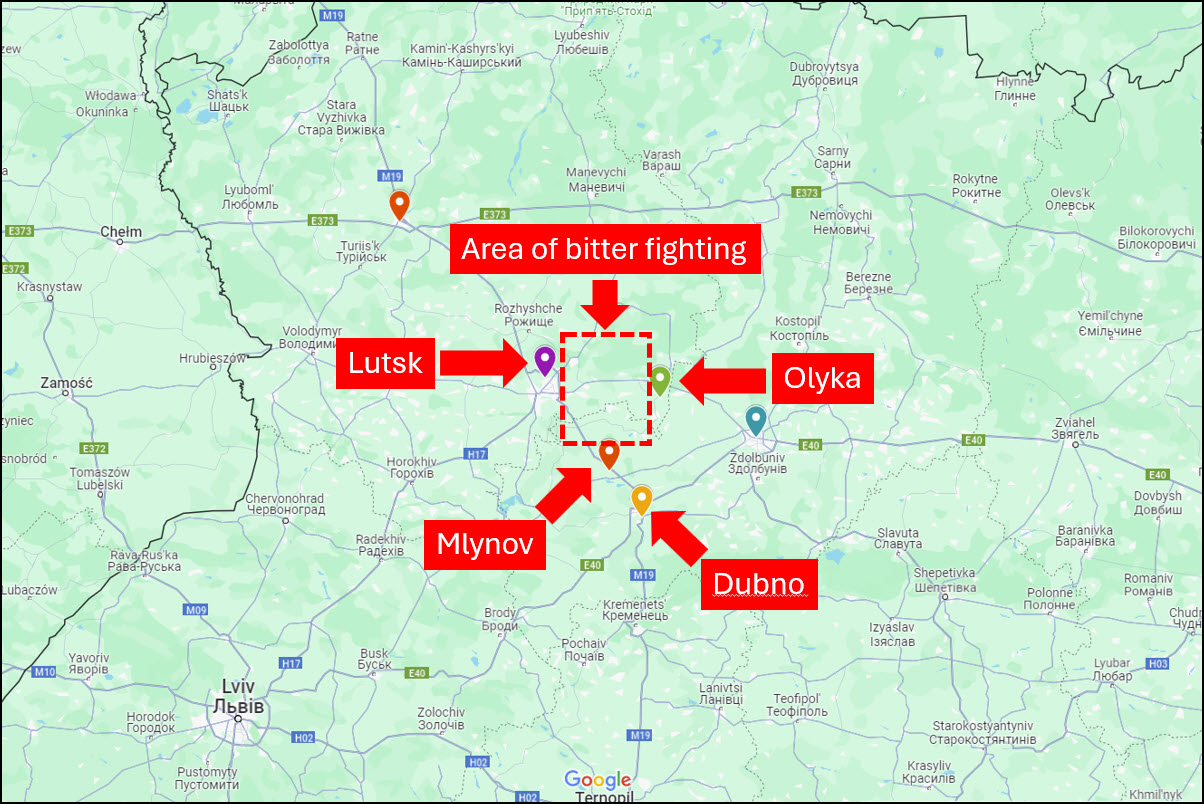

A photo from the Brusilov Offensive. In the public domain[8].The Brusilov Offensive from June to September 1916 is described by one writer as “the Russian Empire's greatest feat of arms during World War I, and among the most lethal offensives in world history.” On the 4th of June, the Russians attacked and immediately penetrated deep into Austrian positions, capturing 13,000 prisoners on the first day. You can see on the map that this attack and the one on June 10th was close to Mlynov. By the time the offensive was two months old, the entire Austro-Hungarian Empire was in danger of falling. But it was also a brutal battle. It took place in an area of present-day western Ukraine, in the general vicinity of the towns of Lviv, Kovel, and Lutsk. As one writer puts it, “Brusilov's operation achieved its original goal of forcing Germany to halt its attack on Verdun and transfer considerable forces to the East. It also broke the back of the Austro-Hungarian army, which suffered the majority of the casualties.”[13]

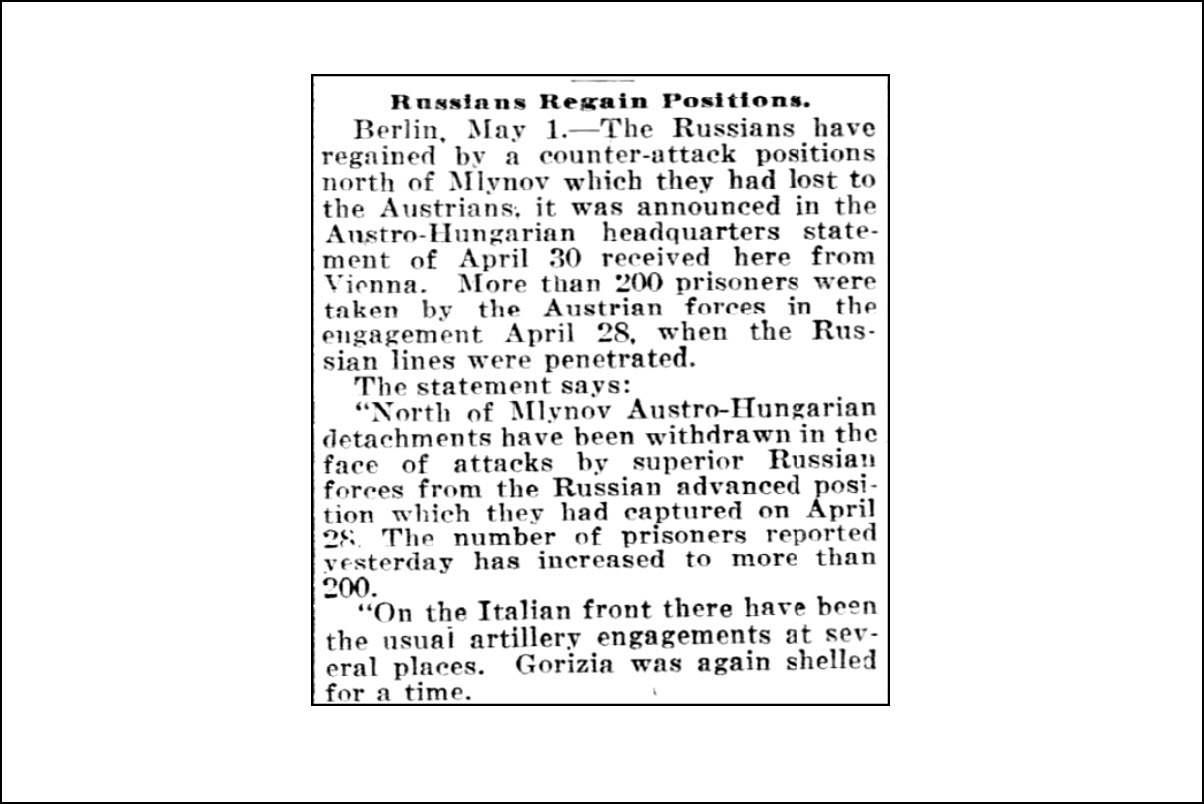

On May 2, 1916 (p. 9) Mlynov is mentioned for the first time in the Baltimore Sun as part of a larger story about the battle over Verdun on the Western Front. This date is near the beginning of the Brusilov Offensive and indicates that attacks by Russian forces north of Mlynov are forcing Austro-Hungarian troops to withdraw. A month later about ten US newspapers carried “a special cable dispatch” that referenced bitter fighting near Mlynov. For some reason, the Baltimore Sun didn’t carry this story so it is possible the relatives living there didn’t know about it.

In this next version of the story on June 8, 1916 (p. 7) from The News from Frederick, Maryland, the Australian War office emphasized that "the Russian forces are continually becoming stronger between Mlynow, on the Ikwa, and the area northwest of Olyka." And then later the article reports that "between Mlynow, on the Ikwa, and the regions northwest of Olyka, where the Russians are continually becoming stronger, there is a bitter fighting." One can only imagine the worry of the Mlynov families in Baltimore as they heard about the fighting near Mlynov, though perhaps by this time they knew their families had been evacuated already.

The Brusilov offensive, though successful, eventually failed because of massive casualties, inadequate equipment and falling morale in the Russian army. The economic costs and eventual failure of the June Offensive weakened the Tsarist government, which contributed to its overthrow soon thereafter in February 1917. In late 1916, several nations across Europe began to suffer from mutinies and revolts as troops became disillusioned with the tremendous loss of life. As the bad news at home mounted, Russia slowly edged toward open revolt and the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary edged toward complete dissolution.

Jump back to the top.

***

1917 Russian Revolution / The US Enters the War

It is difficult to know how the Revolution of 1917 affected those who had been living in Mlynov and Mervits. Many if not all were probably still evacuated when the February Revolution toppled the Tsar's regime and brought to power the Provisional Government. Perhaps they were still living in Rovno or Novohrad-Volyns’kyi when the Bolsheviks took power in October that same year. Whether they felt hope that the Tsarist regime had ended or that the Bolsheviks would deliver on equal rights for Jews, we can only surmise.

Mandelkern, writing later from Tel Aviv, recalls the impact of the Revolution on those from Mlynov. After explaining that the Russian Revolution evoked much happiness among the local people the reactions of Jews depended on their station in life.

The Jewish bourgeois and middle class were vulnerable to lose their holdings, therefore they were not pleased with the Communist takeover. The young Jews, in particular, were thrilled with the opportunity for real education and the opportunity to become intellectuals. During the Czar's regime, universities had several quota restrictions for Jewish students. Now universities would permit Jews to enroll along with everyone else. Also, the working class Jews welcomed the revolution."

But while these reactions characterized Jews in Russia elsewhere, that was not the case in Mlynov. Mendelkern writes:

The above description was applicable to many cities in the Pale of Settlement, but not to Mlynov. In the small towns such as Mlynov, the situation was completely different. In fact, the revolution was hardly noticed at all. The main reason was that there was no middle class in Mlynov. The small shop owners were very poor and continuously worried how to earn decent living to support their families. Although they were content with what they had, they were a simple and modest people who did not complain about their position in life. This kind of Jew could not distinguish between an oppressive form of government and a liberator form of government.[14]

One has to take this characterization of Mlynov inhabitants, like most of the memories from this time, with a grain of salt, since Mendelkorn was a leader in the Zionist youth groups, made aliyah, and wrote this looking back at the shetl from Israel, after the Holocaust. Within Zionist ideology, the shetl life represented all that should be left behind. It would be only natural to see the villagers as simple people who could not distinguish the various political impulses rocking Russian empire. Futhermore, the intent of the Bokshevik takeover was not immediately clear and many people across Russia did not know exactly what was coming. In any case, perhaps news that the US had entered the War in April made its way to them and gave them hope that the war would soon end and that they would return home or be reunited with loved ones in Baltimore. But that was not to be.

Three more years of a civil war beset the region, even as Russia terminated its fighting with the Central Powers and announced its intention to conclude a separate treaty at Brest-Litovsk. While the Bolsheviks under Lenin had made clear that they did not want to continue the war, they dragged their feet with delay tactics in early 1918, frustrating the Germans and resulting in the German and Austrian armies rolling across Ukraine past Mlynov and Mervits all the way to Berdichev and Gomel. The Bolsheviks at the time worried that the Germans might even get to Petrograd and try to topple the Bolshevik government. At this time, the refugees from Mlynov and Mervits refugees probably were living under German rule if they had not been earlier.

Jump back to the top.

***

The War As Seen By Mlynov Immigrants in Baltimore

While we do not have much information about the lives of the Mlynov and Mervits refugees in this period in Russia, we do have an interesting window into the lives of Mlynov immigrants who were living in Baltimore during the War years. The war affected them too. Many were were still "fresh off the boats" and grew increasingly worried about their still alien status as the US decided to enter the War.

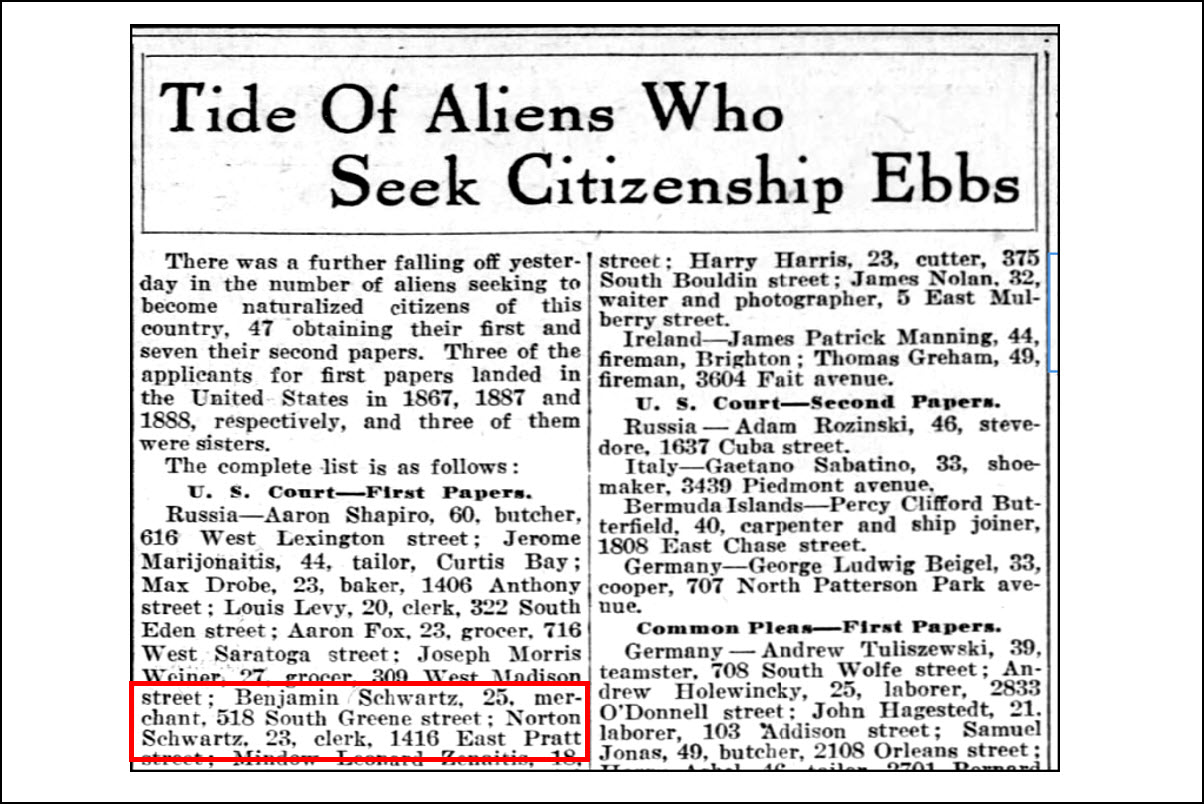

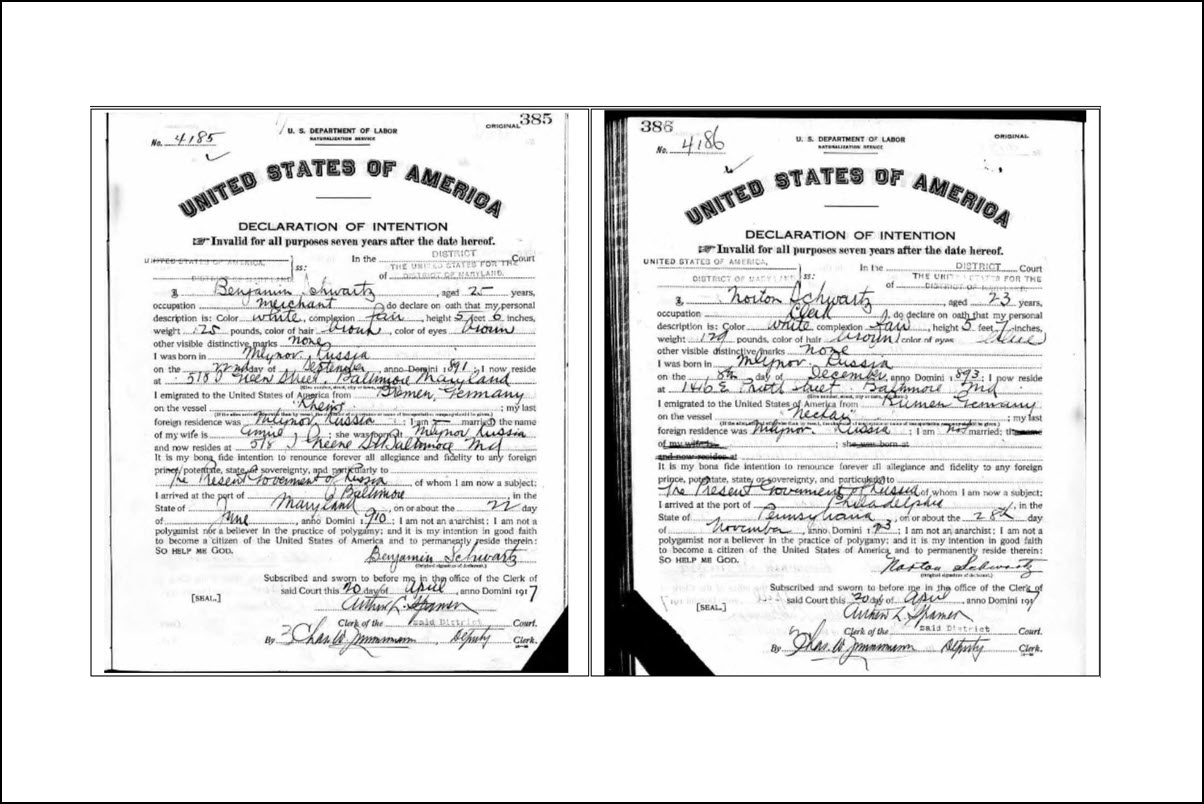

On April 20, 1917 the names of two young men from Mlynov, Benjamin and Norton Schwartz, make their appearance in an article in the Baltimore Sun. The brothers were among a list of resident aliens who had been part of the rush to start their naturalization papers that April, worried about their alien status now that the US had declared its intention to enter the War. Ben, now 25 years old, was the oldest son of Chaim and Yetta Schwartz and had been sent on ahead of the family to Baltimore in 1910. His family had followed him to Baltimore in 1912. Now, just five years later, the US was entering the War.

The Sun had fanned worries among the immigrant communities that month, reminding them that the very possibility of naturalization terminates when the US is at War with a person's native country. For good reasons, German residents in Baltimore dominated the rush to start their naturalization process since the US was entering the War on the side of the Allies, not the Central Powers which included Germany.

Nonetheless, there was a rush on among other immigrant groups as well who feared what the War would mean. Although the US would be joining the war on the same side as Russia, the relatively new immigrants from Mlynov must have worried about whether their hometown would end up in the territory of Russia or Germany as the war progressed, a fear that was not unfounded.

The Mlynov young men must have worried too about the possibility they would be drafted into the War, in what would soon be the first mandatory draft since the Civil War. It was not an idle worry. Over 62,000 Marylanders served in WWI, nearly 2,000 of whom lost their lives. By June of that year, all the Mlynov males now in Baltimore who were between the ages of 21 and 31 years of age had to register for the draft. It was clear that none of them wanted to serve, since all of them tried to seek an exemption on their registration cards. All of the male Mlynov immigrants, as far as I can tell, escaped the draft and only one decided to volunteer.

***

The Bolshevik Revolution and the Family Bar Mitzvah

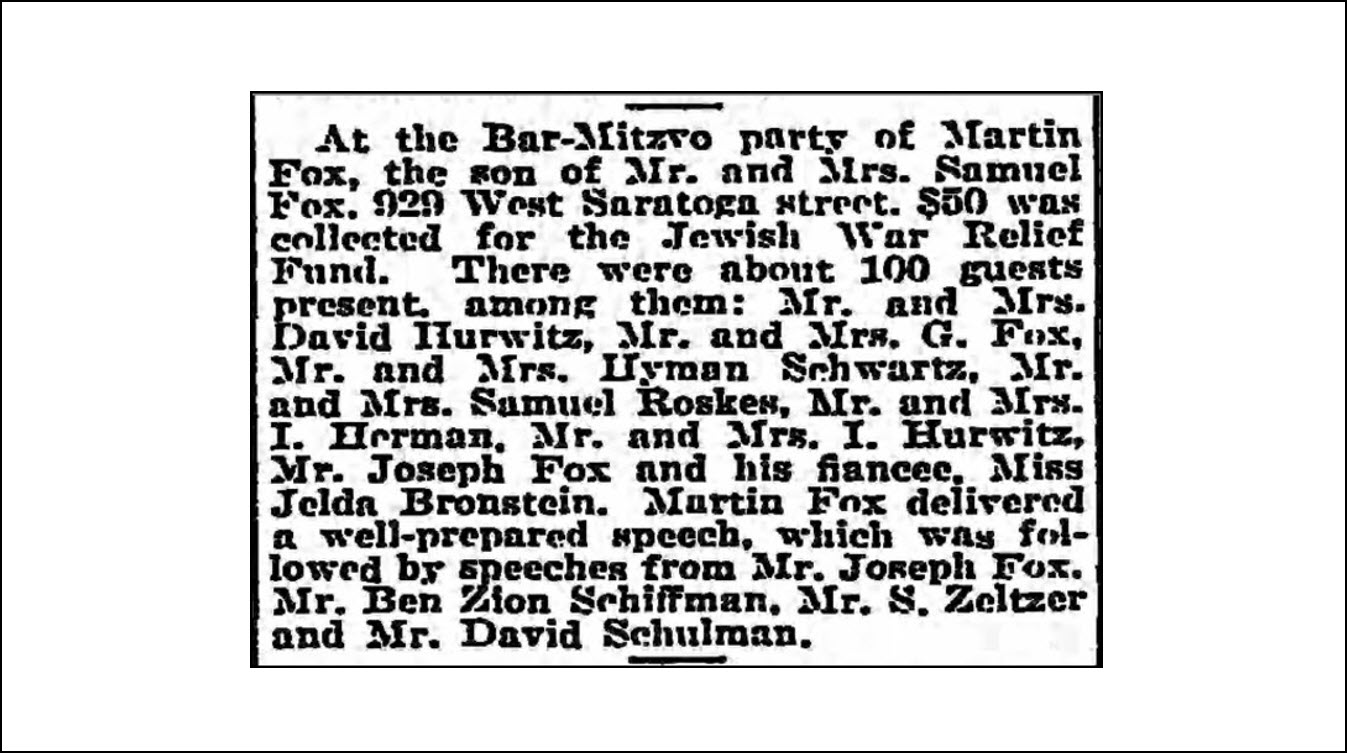

Sometimes mundane artefacts left behind illuminate the lives of ordinary people whose names do not otherwise appear in history books that document the events of an era. Such is the case with the notice of a family bar mitzvah that appeared in the society pages of the Baltimore Sun November 18, 1917, (p. 36). In a way, the notice is both surprising and poignant.

The bar mitzvah was of Martin Fox, the nephew of Getzel and Ida Fax, the first Mlynov pioneers to Baltimore, who had arrived in 1890–91. It had been nearly twenty years since Getzel and Ida had arrived in Baltimore. Getzel's brother, Sam Fox, had arrived in 1905 and had two children with his first wife, before he was widowed and remarried. Martin was his eldest son, the third child to be born to a Mlynov immigrant in Baltimore, and the second to have a bar mitzvah.

The appearance of the bar mitzvah notice is itself surprising. It was not that common at the time to announce a family bar mitzvah in the Baltimore Sun. It was a large occasion as well, bringing together 100 families, a number of which are named in the article. Most of the names mentioned were immigrants from Mlynov and their relatives showing how a substantial group from the small village had replanted itself and continued its village and family ties in Baltimore. There was the Hurwitz family, the Schwartz family, the Roskes, the Hermans, and Foxes, among others. In a way, the bar mitzvah celebration and its announcement in the Sun society pages captured the shift that was starting to take place in the Mlynov story from Russia to Baltimore. The immigrants had created a "little Mlynov" in the growing city of Baltimore. And they had started to absorb the ways of American culture.

The announcement was poignant too, appearing only 9 days after the Baltimore papers reported that the Bolsheviks had toppled the Provisional government. That November no one was yet sure what the second wave of the Revolution meant. The Baltimore family may have initially held out some hope and optimism. The Bolsheviks had promised to terminate the war effort which had devastated the Russian army and created various forms of economic hardship. The US, of course, had only recently entered the war on the side of the Allies (which included Russia) and a decision by Russia to pull out of the war was worrisome for the US and Allies in general. For Baltimore Jews, the second wave of the Revolution would have been deeply unsettling, for it would have been unclear what the toppling of the Provisional Government would mean for Jews still living under Russian rule. Would it be better or worse for their loved ones in war-torn Russia? Perhaps the Mlynov immigrants knew that the Bolsheviks wanted to end the war, and held out hope that their rise to power would mean peace. Matters ended up being much more complicated.

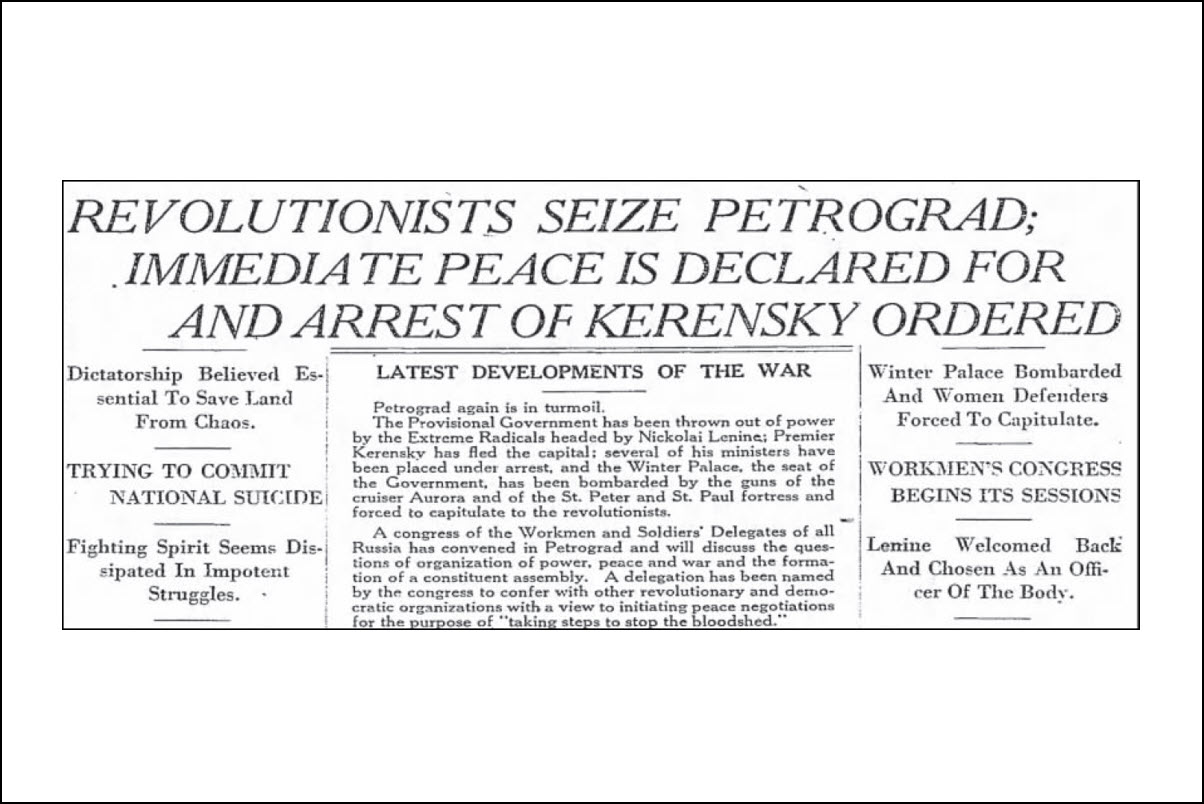

One can see in the news articles about the Revolution that month that there was worry that chaos might ensure, as was in fact the case in the ensuing Russian Civil War, that lasted from 1918–1922. On November 17, 1917 (p. 1), the same day as Martin Fox's bar mitzvah, the Sun reported that Kerensky, the premier of the Provisional Government, had fled disguised as a sailor and that the Bolsheviks had assumed power. By November 24, 1917, just a week after Martin Fox’s bar mitzvah, “Lenine,” (as he was referred to in the Baltimore press) was announcing that the Russians would begin a reduction of their armies and begin releasing Russian soldiers from conscription. Might the cessation of hostilities between Russia and the Central Powers mean peace for the refugees who had been evacuated from Mlynov and Mervits? We do not know whether the Mlynov immigrants in Baltimore already anticipated the chaos and Civil War to follow, but the political turmoil certainly must have been of worry. What would be the fate of the family that had been living in Mlynov?

The celebratory bar mitzvah announcement, which appeared in the Sun on November 18, 1917 (p. 36), indicates that the family and guests raised $50 for the Jewish War Relief Fund. Jewish relief efforts had been going on throughout 1916–1917 and compared to what had been raised in earlier efforts, what the bar mitzvah party raised was not a lot of money. For example, Jacob Epstein, Baltimore’s most prominent philanthropist, and the founder of the Baltimore Bargain House, one of the country’s largest mail order firms, had given $9,000 to the war relief effort and was contributing $1,000 a month, according to an announcement on April 28, 1917 (p. 14). By March 1917, (p. 4), $70,000 had been raised for the Jewish Relief Fund in one week. Nonetheless, fifty dollars was still substantive in that year and equivalent to $800–$2400 today. By a rough estimate of today’s standards, each person at the event gave on average $240 dollars per individual at the event, not an insubstantial sum for families still working in the garment industry or running mom and pop grocery stores. The fact that the family felt the need to raise the money and publicize it in the society pages is indicative of the emotional turmoil and worry that they must have felt at the time.

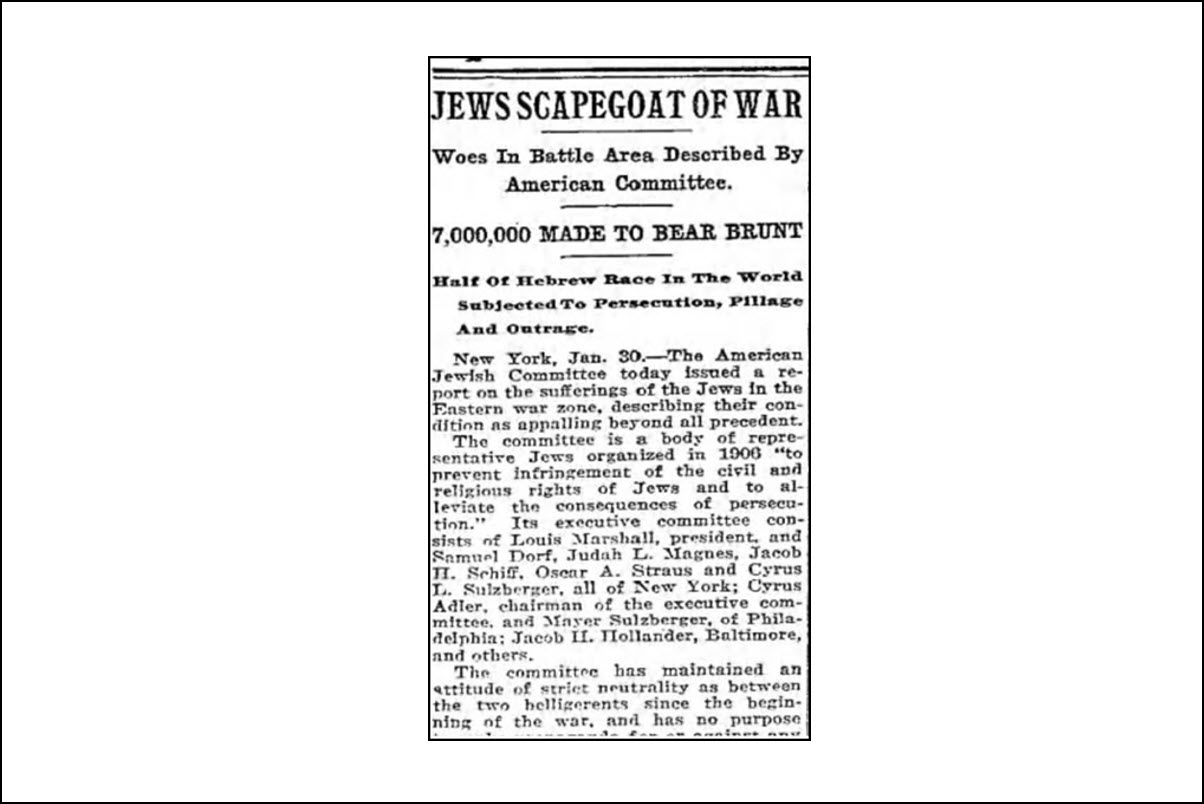

We might speculate the family felt some discomfort celebrating in Baltimore while their relatives and other Jews were still suffering in Europe. Articles about the suffering of Jews in Europe as a result of the war had been appearing in the Baltimore Sun throughout 1916-1917.

In this article, from January 31, 1916, for example, the Sun covered a report from the American Jewish Committee, a body organized in 1906 “to prevent the infringement of the civil and religious rights of Jews and to alleviate the consequences of persecution.” The executive committee was a veritable collection of “who’s who” in the New York Jewish community including Louis Marshall, who acted as president, and Cyrus Adler, among others. This was before the US had entered the war and the article notes that the sympathies of committee members at the time were themselves divided between the warring powers; the report was careful to maintain strict impartiality.

The report of 120 pages covered what was going on in Russia, Galicia, Romania and Palestine. The Russian section was the largest. “The report shows that the 7,000,000 Jews affected, who constitute one-half of the Jewish population of the world, have, because of their unfortunate geographic position, actually borne the brunt of the war's burdens in Eastern Europe. When the war broke out they found themselves trapped, absolutely shut off from all neutral lands and from the sea-- in the region of Russian Poland, Austrian Galicia and the Russian Pale. According to the report:

They were overwhelmed where they stood and over their bodies crossed and recrossed the German armies from the west, and the Russian armies from the east, and the Austrian armies from the south. True all the peoples of this area suffered ravage and pillage by the war, but in no degree comparable to the sufferings of the Jews. The contending armies found it politic, in a measure, to court the good will of Poles, Ruthenians and other races in the area. These suffered only the necessary and unavoidable hardships of war. But the Jews were friendless, their religion proscribed. In this medieval corner of the world, all the religious fanaticism of the Russians, the chauvinism of the Poles, combined with the blood lusts liberated in all men by the war–-all these fierce hatreds were sluiced into one torrent of passion which poured itself upon the Jews.

The report continued: "Hundreds of Jewish towns have been sacked and burned wantonly by the Russian soldiers. Thousands of Jews have been carried off as hostages, imprisoned, executed on the flimsiest pretexts or shot in wanton cruelty. Women were outraged and men burned alive in the synagogues where they had fled for shelter. Orgies of lust and torture took place in the light of day. Women, old and young were stripped and knouted [whipped] in the public squares."

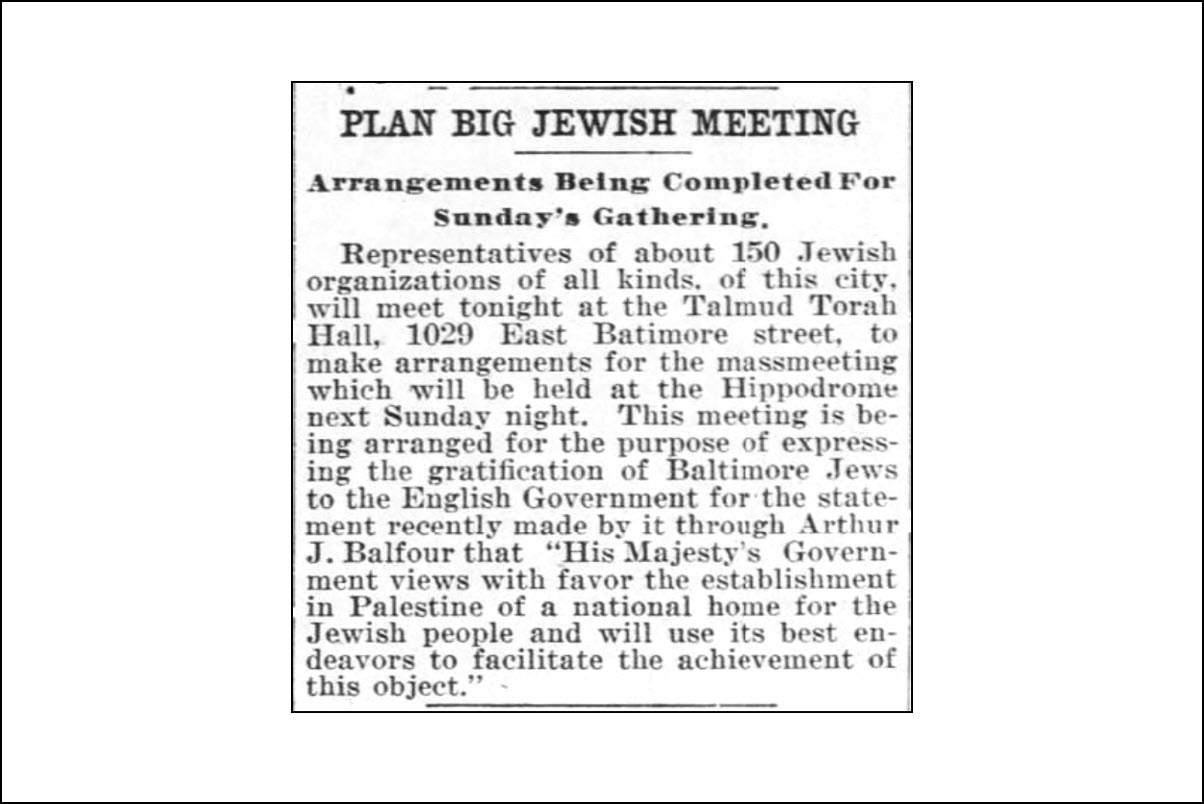

That same November that the Fox bar mitzvah took place, there was another event that had deep significance for parts of the Jewish community, though we have no idea whether the Mlynov immigrants were aware of it. On November 9, 1917, the press published the text of the Balfour Declaration. The declaration contained in a letter dated November 2 from the United Kingdom's Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, was to be transmitted to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917. It stated that: "His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

The first part of the declaration was the first public support for Zionism by a major political power. The term "national home" had no precedent in international law and was intentionally unclear as to whether a Jewish state was intended. Historians thus disagree as to what the then British Foreign Secretary, Arthur James Balfour, intended by his declaration. The timing of the news coincided with British victories in Palestine and the retreat of the Turkish army.

While the news of the Balfour Declaration appeared in many other papers in the US during the early weeks of November, the news didn’t appear in the Baltimore Sun until November 28th, after Martin’s bar mitzvah. But the news clearly had penetrated the community by that time since the article headline reported that 150 Jewish organizations “Plan Big Jewish Meeting.” The event was “for the purpose of expressing the gratification of Baltimore Jews to the English Government for the statement recently made by it through Arthur J. Balfour that ‘His Majesty's Government views with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people and will use its best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.’”

Jump back to the top.

***

Brest Litovsk Treaty and The Russian Civil War

When they assumed control of the government in late 1917, the Bolsheviks wanted to get out of the War as soon as possible and concentrate on consolidating their power. After telling Germany they wanted to negotiate a separate peace, the Bolsheviks engaged delay tactics for several months, not happy with the terms that the Germans wanted to extract in territories and hoping that a revolution would begin in Germany itself, a hope inspired by worker strikes that were occurring. Realizing the Bolsheviks were delaying, the Germans and Austrians in February 1918 rolled their armies across Ukraine past Mlynov with no real resistance and reached Bedichev and Gomel putting fear in the Bolsheviks that they would reach Petrograd.[15]

During this period, the families from Mlynov and Mervits may very well have fallen under German or Austrian jurisdiction. An oral tradition passed down to a Baltimore descendant may very well refer to this period. Reflecting back after WWII, Ben Fishman, with deep intentional irony, recalled that the Germans who came to town in WWI were so much more respectful than the Russian soldiers. The German soldiers were respectful and didn't steal your goods, Fishman recalled, whereas the Russian soldiers commandeered the house and all that was in it.[16]

When Russia finally capitulated and signed the treaty in March 1918, the treaty took away territories that included 26 percent of Russian's inhabitants, 37 percent of the agricultural harvest, 28 percent of industrial enterprises, 26 percent of the railway tracks and three-quarters of the coal and iron deposits. [17] Germany also imposed the requirement that Ukraine be recognized as an independent state, with the expectation that the territories it had acquired would be under German control. From the Bolshevik perspective, an independent Ukraine posed a threat, offering a dangerous base for anti-Bolshevik military activity in the subsequent Russian Civil War that ensued (1918–1922). Indeed, many Russian nationalists and some revolutionaries were furious at the Bolsheviks' acceptance of the treaty and joined forces to fight them.

The period from 1918–1922 saw the emergence of a complex civil war that involved the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921) which was part of a wider Russian Civil War of 1917–1922. Fighting occurred between Ukrainian nationalists, anarchists, Bolsheviks, the forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary, the White Russian Volunteer Army, and the Second Polish Republic forces. The struggle lasted from February 1917 until November 1921 and resulted in the division of Ukraine between the Bolshevik Ukrainian SSR, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. Poland re-emerged in November 1918 after more than a century of partitions. Its independence was confirmed by the victorious powers through the Treaty of Versailles of June 1919, and most of the territory won in a series of border wars fought from 1918 to 1921. Poland's frontiers were settled in 1922 and internationally recognized in 1923.[18]

During this period, there were a serises of brutal pogroms that were perpetuated by all parties to the conflict and had multiple causes. We know little to nothing about how Mlynov and Mervits residents were faring during this time. The Yivo Institute provides a good summary of the complex causes of the pogroms:

The Russian Civil War was fought on many fronts between 1919 and 1921. It was waged by disparate groups, motivated by politics (the Reds and the Whites), nationalism (Ukrainians and Poles), social protest (the agrarian Greens), and simple greed. The absence of any strong central authority ensured that the entire civilian population was victimized by one military force or another. All the contending armies, regular and irregular, conducted pogroms against Jewish communities. Only the commanders of the Red Army occasionally punished troops guilty of pogrom-mongering. The White forces often used antisemitism as a tool for ideological mobilization. Two groups were particularly prone to pogroms, the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army commanded by General Anton Ivanovich Denikin, and forces loyal to the Ukrainian national government, the so-called Directory, headed by Simon Petliura. The irregular forces fighting in the name of the Directory, the Otamans, were particularly notorious for anti-Jewish murder, torture, and rape. Antipogrom declarations issued by the Directory were decried by Jewish groups as mere window-dressing. In fact, the Directory had little effective control over the forces fighting in its name.[19]

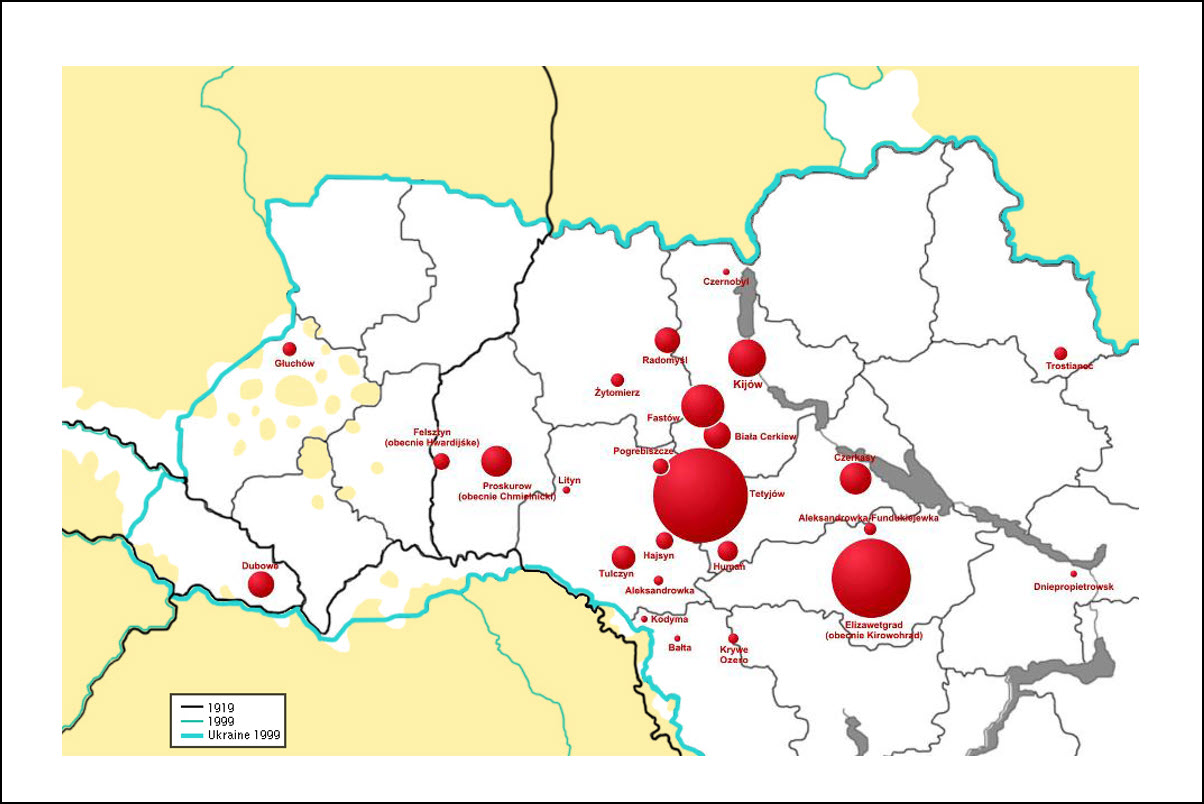

Map of Pogroms in Ukraine 1918-1920. Courtesy of Wojciech Winkler, contributed to public domain.

Map of Pogroms in Ukraine 1918-1920. Courtesy of Wojciech Winkler, contributed to public domain.While ideology no doubt played some role in prompting pogroms, much of the violence was occasioned by the collapse of governmental authority, the brutalization caused by years of inhumane warfare, and a criminal desire to loot and plunder. There are sharply differing estimates on the total number of Jewish casualties during the Civil War, but the minimum credible estimate is 50,000 fatalities.

The most notorious attacks were carried out by Poles in Lwów from November 22 to 24, 1918, and in Pinsk on April 5, 1919. The Kiev pogrom in 1919 was carried out by the White Army. Professor Zvi Gitelman, in A Century of Ambivalence, estimates that in 1918–1919 over 1,200 pogroms took place. The Kiev pogrom of 1919 was the first of a subsequent wave of pogroms in which between 30,000 and 70,000 Jews were massacred across Ukraine.[20]

There are no surviving stories to date of Mlynov or Mervits families that were killed by these pogroms though we know that Yitzhak Lamdan's brother was killed in the fighting between the parties in the Civil War. The reflection of Samuel Mandelkern from Mlynov on pogroms appears to come from an earlier period, around 1916. He writes:

Many Jews in small villages did not believe that pogroms could happen in their communities; it was the kind of thing you only heard about, that happened elsewhere. Indeed, this was the feeling shared by the majority of Jews in Mlynov...

The pogroms in Mlynov were instigated by the soldiers in the Czar's army, not revolutionaries. Many soldiers had settled in Kiev and Zhitomir and army divisions were extended down to the Carpathian Mountains. Many soldiers became friendly with the Ukrainian villagers in the region because they provided the soldiers with food and clothing. In return, the army permitted and encouraged the Ukrainians to rob, rape and steal from the Jews.

Pogroms in Mlynov typically began at night when a few soldiers would ride into the town on white horses, approach a Jewish house, knock on the door and ask for directions. As soon as the person inside would open the door, the sodiers would barge in, attack the people and rob them of their belongings. They would then proceed to other houses.

Finally, some Jews protested and suggested that a defense league be established. Initially, the community leaders most of whom were religious, supported the defense league. However, they imposed one condition–they objected to the use of guns, and suggested using sticks instead. Most of the people disagreed with the community leaders, pointing out that the soldiers had guns and that sticks would be ineffective in fighting against guns. Yet, the people did not wish to disobey the elders, and the league was establised with sticks as weapons. The result was that the pogroms continued and the situation did not improve.[21]

At the end of the Civil War, Mlynov and Mervits ended up under Polish rule and by 1920 a number of Mlynov and Mervits refugees had started to return to the village and the situation had stabilized enough that some had begun to make plans to leave. It is to these post-war stories that our attention now turns.

Jump back to the top.

***

Aftermath of War

One way to gauge the War's impact is by the subsequent decisions to leave by many of the returning inhabitants after the War. It is clear from those decisions that a significant emotional toll had been exacted during the War years and that many lost hope in their lives under the newly constituted Polish rule.

To be sure, some of the families came back and rebuilt their lives in the villages and stayed. As examples, Mendl Teitelman who was quoted previously and his wife Sonia, stayed in Mlynov. So did Aaron Harari and Samuel Mandelkern, who were quoted previously. They either felt that life would improve or they lacked the means to leave. The increased interest in Zionist Youth Groups during the period indicates that even among those who stayed, their hopes had shifted elsewhere. But a number of returning families made the decision to emigrate, some who had the capability and wherewithal going to America and Baltimore in particular, as immigration opened again. By this time, they had probably heard that the Mlynov immigrants in Baltimore were doing quite well and indeed some of their relatives would come back to Mlynov after the War to help them get to the States. Others chose to emigrate ("make aliyah") to Palestine, if they felt the pull in that direction. Some families, as we shall see, split between these options.

The first to leave were those who had been separated from and unable to rejoin their husbands who had migrated to Baltimore before the War started. The families of Aaron Demb, Joseph Lerner and Isaac Marder had survived the War and in early 1920 made plans to rejoin their husbands in Baltimore. They were helped by Joseph Lerner's son, Itzhik (Isidore) Lerner, who was sent back from the States to help his mother and siblings with their preparation and travel. Isidore, a boy originally from Mlynov himself, had migrated to Baltimore in 1913 to join his father. But the War had broken out and he had served in the meantime in the US military. According to his military records, Itzhik had actually served overseas during the War between October 1918 and February 1919 and was honorably discharged and returned home in March of that year. According to oral traditions told by Ben Fishman, who traveled to Baltimore with these families, Isidore brought his army uniform with him when he came back to Mlynov in 1920. The uniform came in handy according to oral traditions:

According to the story, Itzhik used his army uniform to empower the Jewish families to travel on the train in first class on their way to Warsaw, where they sought their papers to leave. Traveling first-class was reportedly unheard of for Jewish families at the time. When they got to Warsaw, according to the narrative, the Polish official gave young Ben Fishman a hard time about giving him immigration papers. So Itzhik Lerner went outside, donned his US military uniform again, and went back in and demanded the papers be provided, whereupon the Polish official immedately complied.[22] Itzhik accompanied the three families back to the States in June 1920 bringing a new wife, Gitel (Gertrude), with him.

Jump back to the top.

***

The Fishman family presents a telling example of the conflicting impulses of the period experienced by those who had returned after the War. The family split up in 1920 and 1921 between America and Palestine. In 1920, Ben Fishman, the second of three children, was sitting around with the group of Mlynov families (the Dembs, Marders and Lerners) discussing their plans to leave for America. According to his account, his friend Ertz Shulman, in what is reportedly to be a kind of tease, nudged him and said, "Why don't you go." Ben shrugged his shoulders and said, "Why not." And without asking his parents, he decided to join the migrating families that were headed to Baltimore. Perhaps Ben was already in love with his future wife, Clara Shulman, and knew that the Shulmans were themselves planning to head to Baltimore in 1921. Or perhaps he heard that his cousin, Morris Goldseker, was doing quite well in Baltimore in real estate by this time. In any case, he made the decision to leave without asking his parents though they subsequently blessed his decision and gave him money before leaving.[23] You can hear Ben speak about leaving his parents at this time in this video clip later in life.

In June 1920, Ben at the age of 18 left his family in Mlynov and joined the Mlynov families of the Lerners, Marders and (Aaron) Demb who headed to Baltimore to rejoin their husbands. We don't know exactly what was said between Ben and his parents, Moishe and Chava, when he made his decision to go to America. But we do know from accounts that we have, that his parents chose Palestine out of a commitment to the Zionist vision of a national home. The moving photo of Moishe, Chava and Ben's siblings shown here has a photo of Ben sitting on the table leaning up against a mug. It was taken in 1920 after Ben left and before they headed to Palestine. Ben's parents, Moishe and Chava Fishman, and his siblings, David and Chuva Fishman, arrived in Palestine and were among the first founders of Moshav Balfouria in 1923, named for the author of the Balfour Declaration. You can watch and listen to Ben reflect onthis moment of his life when he took leave of his parents in 1920.

Boruch Meren recounts the excitement and disbelief when the Fishmans announced they were leaving for Palestine at the time:

The year was 1921. Mr Moshe Fishman, or as he was called–Moishe Tobeys–a middle-aged, energetic man with a short red bead, announced to his Mlynov friends and neighbors that he and his wife, his older son and his daughter, were planning to leave for Palestine. The news spread quickly over the entire town. At first, no one believed it. But they soon found out that Moishe had already prepared all the necessary legal papers, had obtained the passports, and he began to sell his possessions and property. They found it difficult to believe in his adventure. It was the talk of the town in the synagogue, in the marketplace, and even the local peasants told each other about the news.

Everyone spoke about Moishe Fishman who was going to Palestine to become a Jewish farmer. Children spoke about the family with piety and jealousy. Some people said that the Fishman family would walk on the holy ground of Palestine and would eat oranges, figs and almonds. Others said that the Fishman family had to be crazy to do such a thing. After all, Moishe Fishman had his own house, a cow, a horses [sic], a small store, and he made a fairly good living; he was a well-respected person, a member of the Trisker synagogue, and had a seat facing the Eastern Wall.

How could he do such a thing and leave behind everything in order to go to an empty, deserted land where Arabs attack, kill and rob? Friends tried to persuade him not to leave, but it was in vain. His reply was "I am tired and disgusted with the Poles and their anti-semitism. I pity the poor Jewish storekeepers who stand in their little stores, anxiously looking for a customer. I will be a Jewish peasant, work hard in the fields to make a living for my family, but I will be happy because I will be in my own free land." These were Moishe Fishman's words.

There were five members in his family. He and his wife, Chaya, his older son, David, his younger son, Berel, who had already left for America, and a daughter, Chuva. The older son, David, helped his father in their little store. But David's mind was not on business; he was an ardent Zionist, always busy reading a Hebrew book or magazine. He was 20 years old, and had a good, strong physical build. Moishe knew that David would be his helper.

I will never forget the parting of the family. The enitre last night before their leaving, their house was full of people who came to wish the Fishmans good luck. It was a dramatic scene, kissing, hugging, and wishing them a safe journey. The luggage was in the next room. The Hebrew teacher, Eisenberg, brought his pupils from school and they all sang Hebrew songs. At the end, they sang Hatikva. We returned to our homes late that night. The next morning, people came to help the Fishmans load their luggage onto the sled. They received good wishes from their friends and neighbors. They finally said, "Shalom," and the sled started in the direction of the city Dubno. Some people remained standing in front of the empty house and barn, wondering and admiring Moishe and his family for their bravery and courage, leaving everything behind in order to go to "the beautiful, warm free land of Palestine." [24]

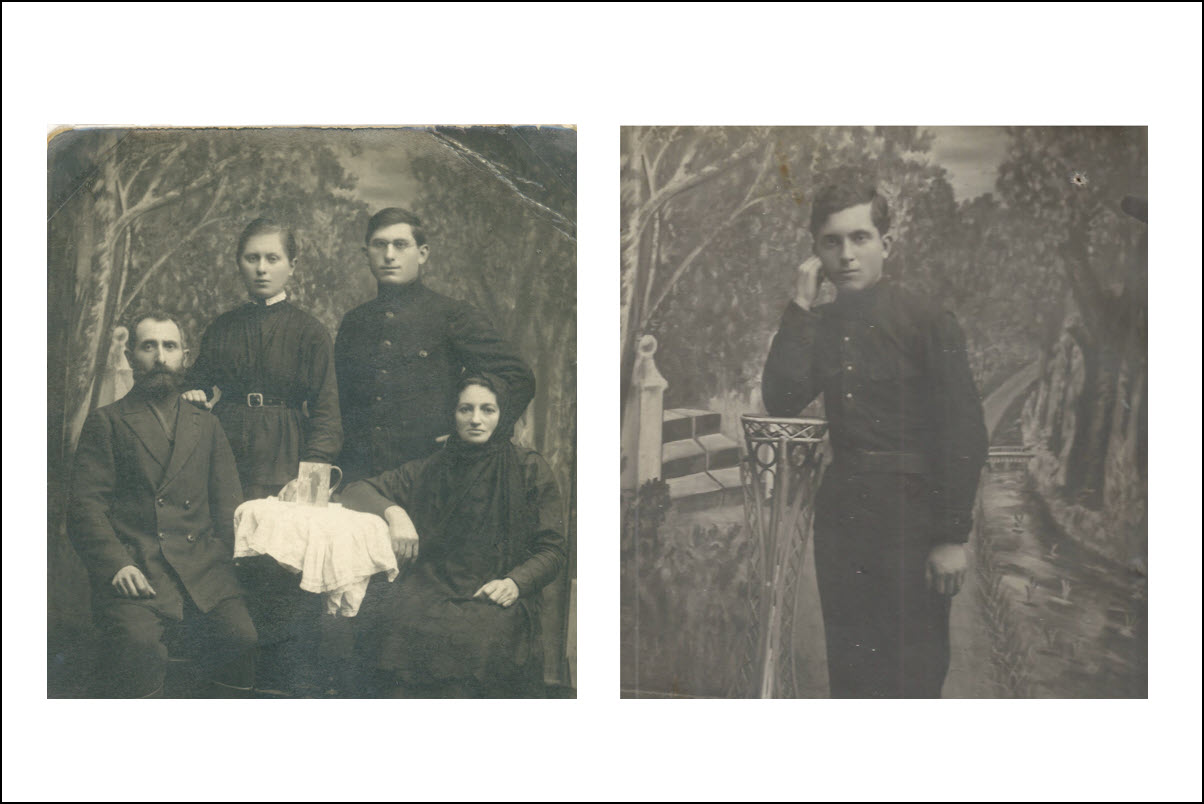

***

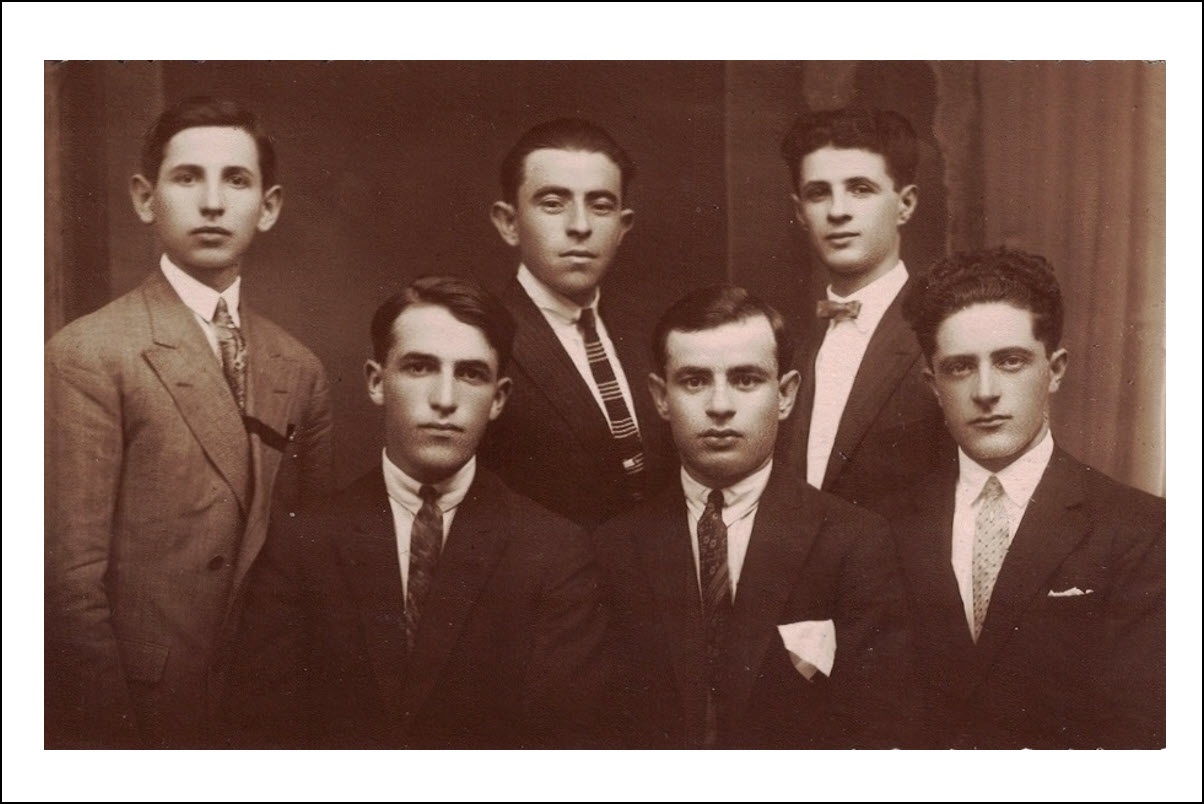

The Shulman family was another large family from Mlynov that in 1921 made the decision to head to Baltimore to join the families of Pearl (Demb) Shulman's three sisters who had already gone to Baltimore. Apparently, the Shulmans had returned to Mlynov after the war and their home had become a kind of cultural center in the town.

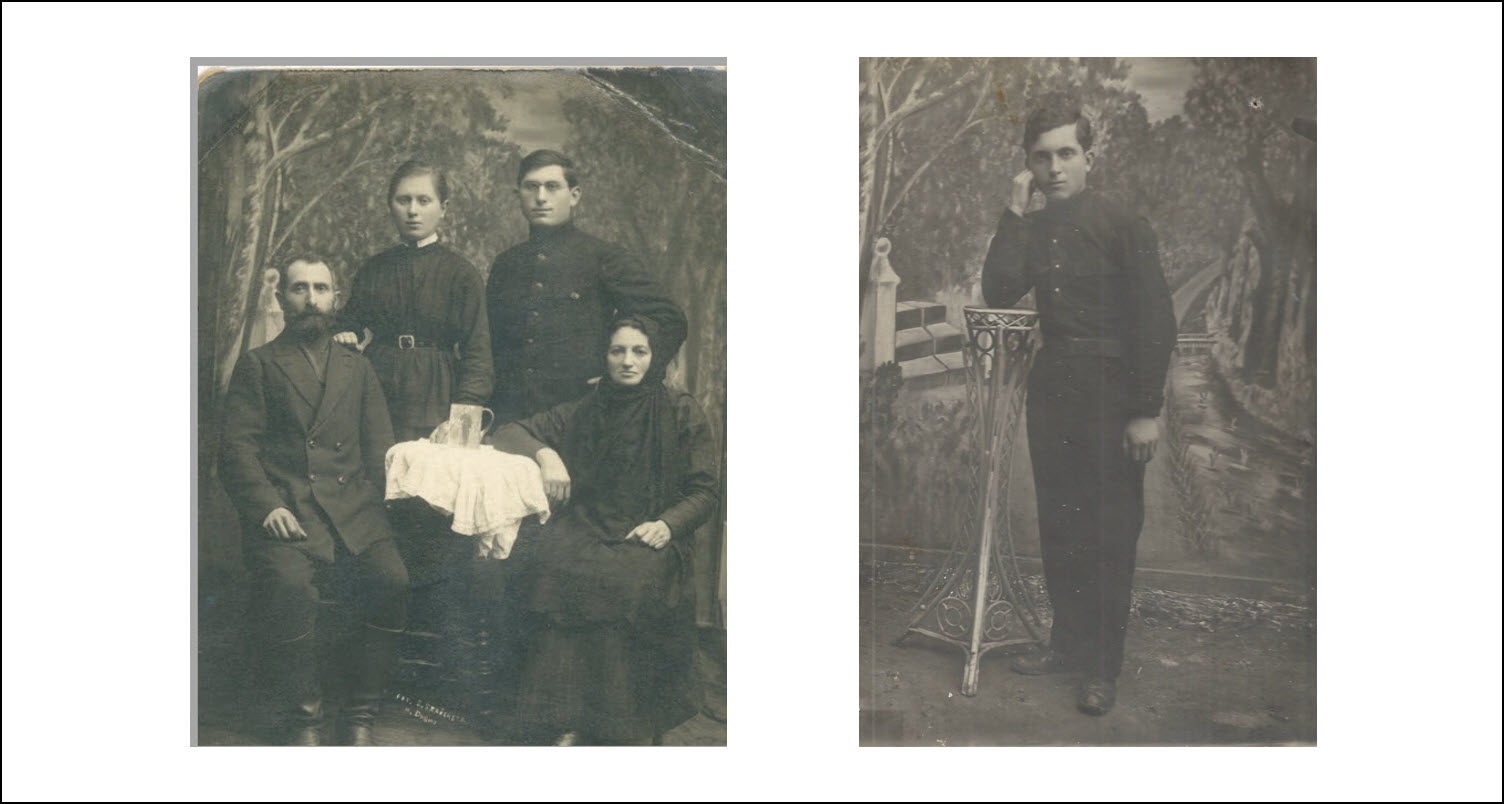

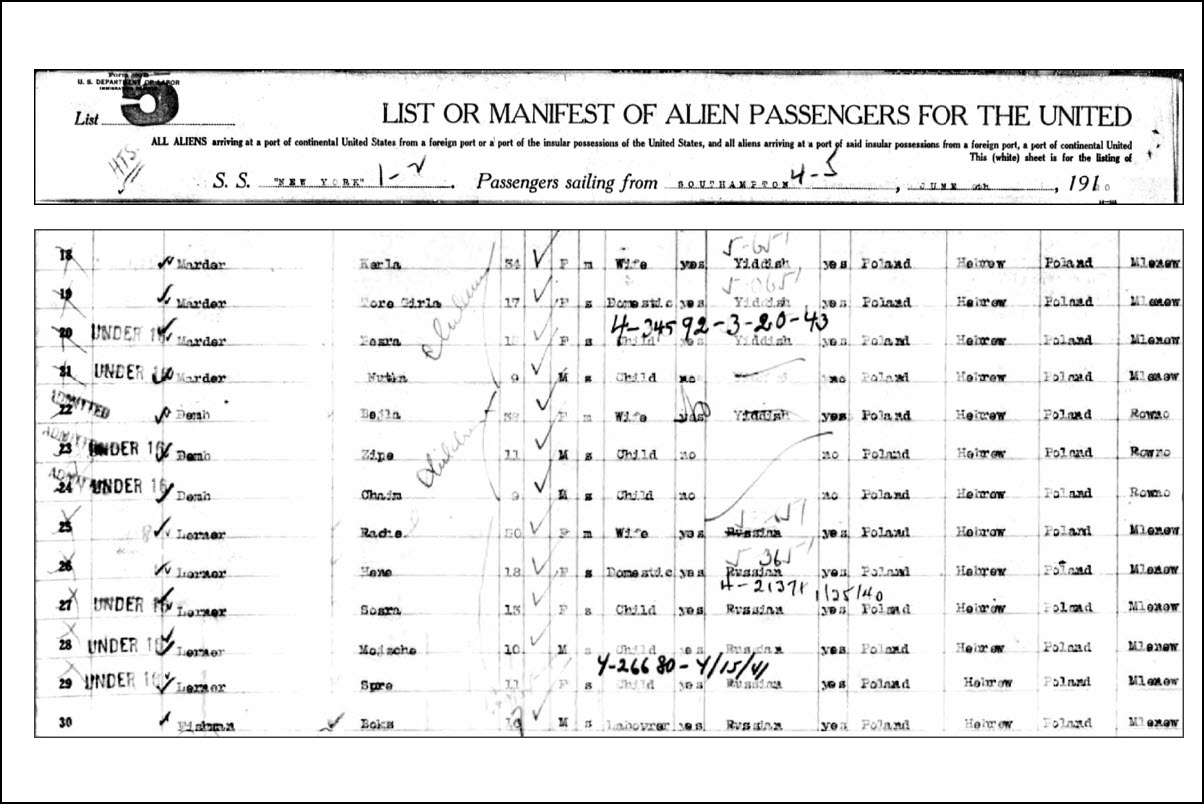

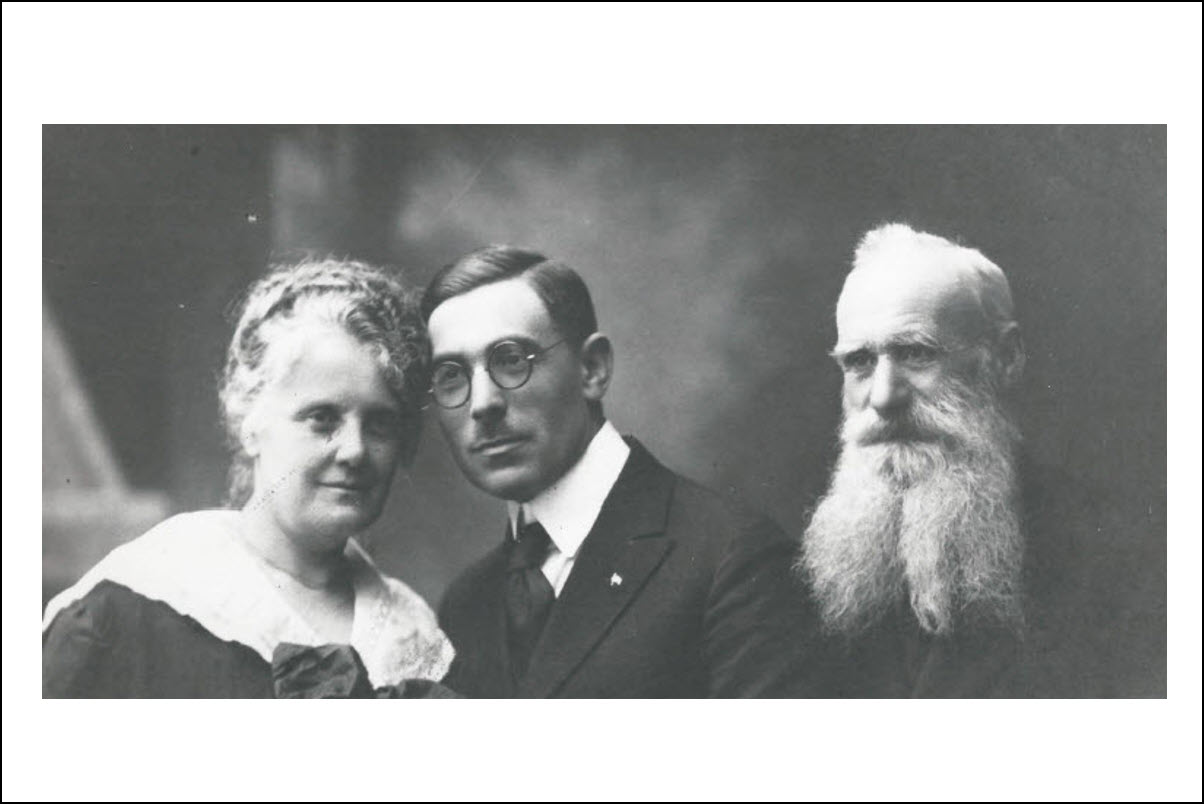

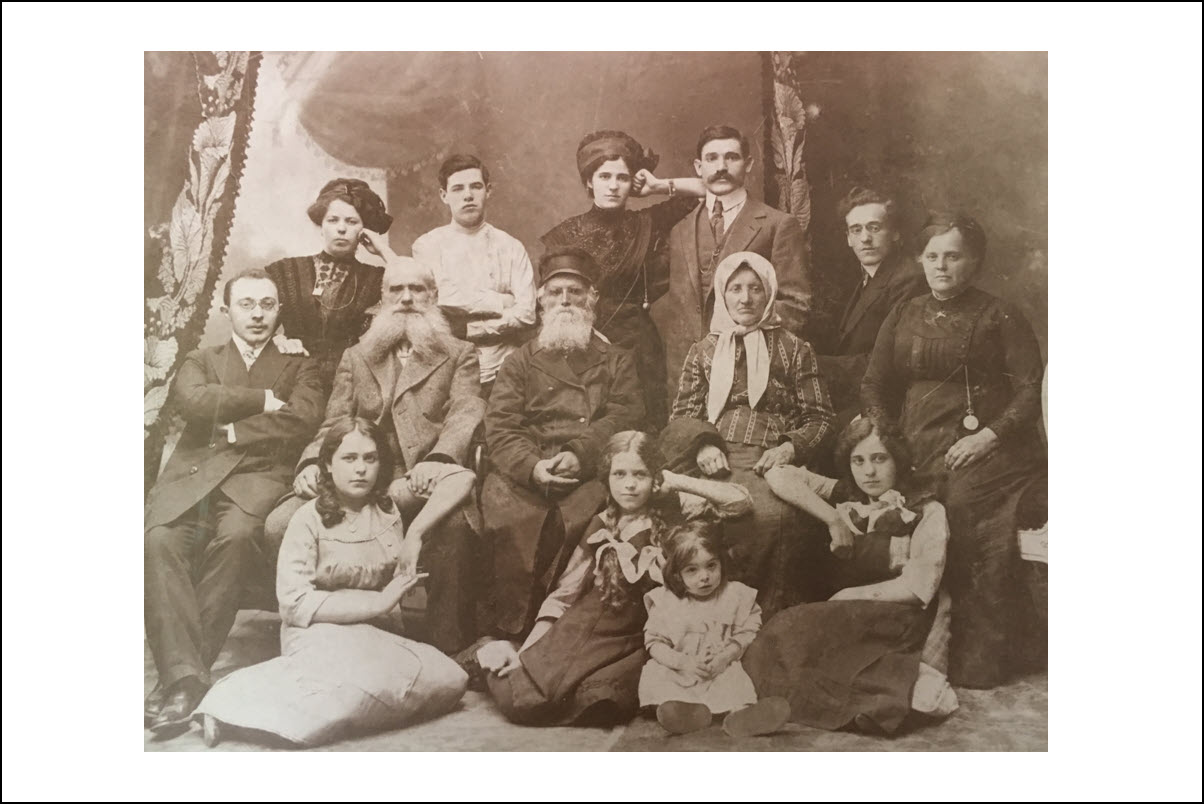

The Shulman family circa 1915 in Mlynov or Rovno. The photo includes four generations of Demb descendants. Israel Jacob Demb and Rivkah (Gruber) Demb (seated center) and children[25] Courtesy of Howard Schwartz

The Shulman family circa 1915 in Mlynov or Rovno. The photo includes four generations of Demb descendants. Israel Jacob Demb and Rivkah (Gruber) Demb (seated center) and children[25] Courtesy of Howard SchwartzAaron Harari, who became involved about this time in the Zionist Youth group, HaShomer Hatsair (Young Watchmen), recalls that Shulman home had become known in Mlynov at this time as a kind of cultural center that was not particularly Zionist. Aaron Harari writes:

During World War I, many people left Mlynov and became refugees in order to escape the heavy fighting. After the war, they returned and tried to establish themselves again. The Jewish community overall had to recover from the war. The house of the family named Shulman became the cultural center in town. They established a library and conducted rehearsals for plays. Because of the heavy Russian influence in town (even though it became Polish after the war) the Russian language was widely spoken in the Shulman house. Most of the books in the library were in Russian, with a few in Yiddish. At that time, there were no books written in Hebrew in the library. The people who frequented the Shulman house were far removed from the Zionist movement. Slowly, however, the Zionist movement began to grow in Mlynov, and those involved with Zionism were more interested in Hebrew culture rather than Russian.[26]

The memory of the Shulman library is consistent too with a memory of Ben Fishman, who had left for America a year earlier. Ben recalled that the Shulmans were well-to-do, "cold cuts" as he later called them, and that the library provided the excuse for a poorer boy like himself from Mervits to hang out with the beautiful Shulman daughters. He later married Clara Shulman in Baltimore. Tsodik Shulman, the father, it may be recalled, was the nephew of the famous Jewish enlightenment figure (maskil), Kalman Shulman, a Hebrew writer whose work was significant in the development of modern Hebrew literature and Tsodik is remembered by others as an enlightenment oriented man himself.[27]

Descendants of the Shulmans speculate that the family left Mlynov at this time because Tsodik lost his job overseeing the Count's forest; why else would they leave their two oldest daughters and their families behind? The Count's palace had in fact been occupied during the war and the lands were seized eventually as the Bolsheviks came to power. It is thought that the loss of the means for a living was the catalyst that got the Shulmans to leave. Like the families that left before them in 1920, the Shulman family was also assisted by a relative who had come back to Mlynov from the States. Tsodik Shulman's nephew, David Shulman, had immigrated to the US in 1901 and come back in 1921 to assist the Shulmans and his wife's family (the Blumenkrantzes from Kovel) to leave.

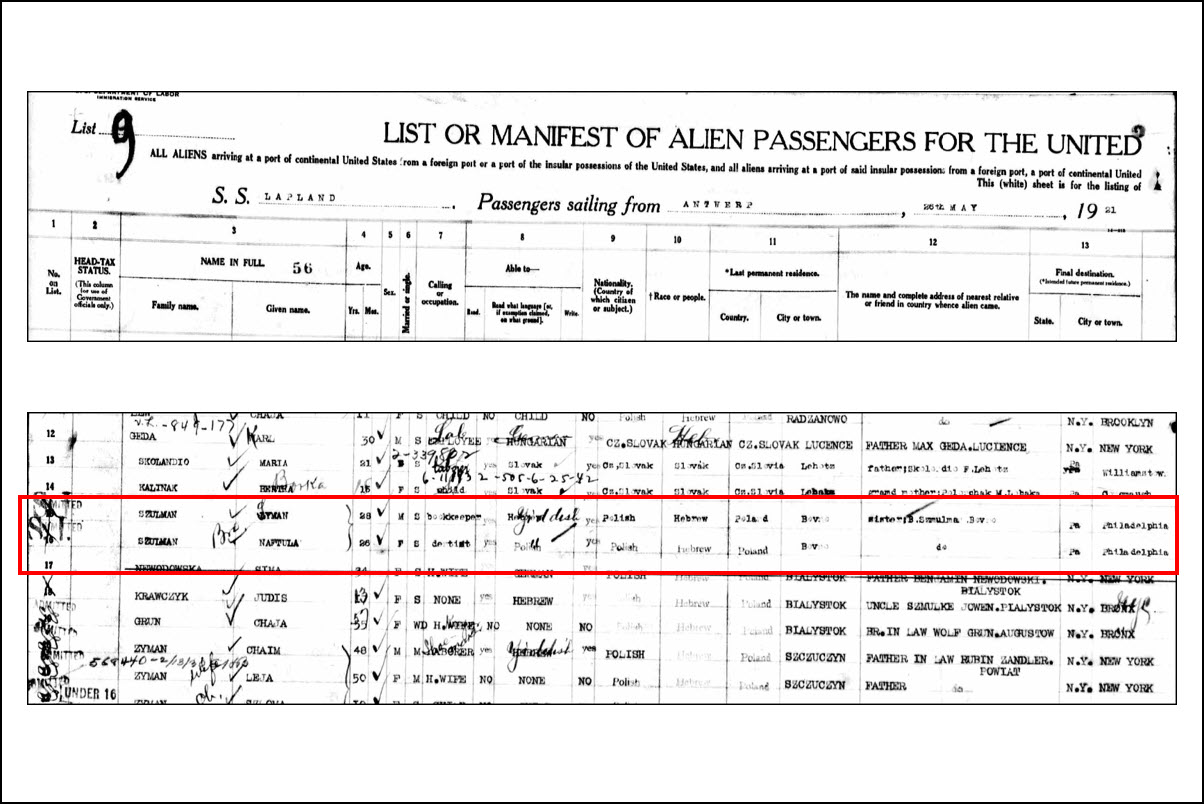

We can detect in the Shulman passenger manifest that the US imigration laws had already begun to tighten as evident by the numerous obfuscations that were involved. To begin with, Tsodik pretended that David Shulman was his son, not his nephew, and that David's in-laws (the Blumenkrantz family) were Tsodik's nieces and nephews. Also pretending to be a daugther of the Shulmans was their son Ertz's wife, Eta (also Yetta) Perelson. According to the oral tradition, Eta's parents only allowed her to leave if she would first marry Ertz Shulman. So a hasty wedding was pulled together at the home of the Blumenkrantzes and Eta and Ertz were married.[28]

Another young man, Pesach Zutelman, also made the passage pretending to be a Shulman son. Pesach was one of the Zutelman brothers reunited in Mervits in the reflection by Mendl Teitelman discussed previously. Pesach pretended to be one of the Shulman sons and traveled under the name of Naftula Szulman. He and Ertz Shulman had swamped identities to get through customs, with Ertz pretending to be his brother, Simon, and Pesach pretending to be Ertz. We can surmise that Pesach Zutelman was prompted to leave his own family and to join the Shulmans due to the experiences of the War years and coupled with the fact that he may already have been in love with Sarah Shulman, whom he subsequently married in Baltimore. There, in Baltimore, he retained the name "Paul Shulman," the identity he had assumed on his passenger manifest, thereby avoiding issues or worse with his naturalization process.

The oldest Shulman son, Shimon, did not join the family on its passage to Baltimore. He apparently had been studying to be a pharmacist in Russia (though Mlynov had become part of Poland at the time) and arrived back in Mlynov to learn that his family had left for America. A year later, he followed them to Baltimore bringing his wife, Edith Fixman, who was from Berdichev, and whom he had met while studying to be a pharmacist.[29]

Pesach Zutelman's older brother, Efraim (Frank), also fled the area a year or two later to avoid conscription into one of the armies, possibly during the Russian Polish Civil War. According to stories he later told his son, his close friend had shot off his toes during this period to avoid conscription and Efraim had not wanted to pursue such a drastic course of action. [30] So he chose instead to flee. By then, the immigration rules had tightened even further in the US. He made his way to Baltimore in 1923 via a stopover in Buenos Aires, like a number of other Mlynov boys who followed him, in a story to be told later.

Jump back to the top.

***

Migration To the US Gets Tougher / Families Split Up

The US eventually imposed quotas on Eastern European immigration making it still tougher to get into the United States. As the 1920s progressed, several Mlynov families split up as they attempted to get into the United States. In 1921, Sonia Demb (Sylvia Penn) left before her parents, Motel and Freida Demb (later Deming), and headed to a relative in Springfield, MA, where she soon was married. Her parents and younger sister followed her to Springfield in 1924 but soon moved to be close to other relatives in Baltimore.

The Mlynov Boys in Buenos Aires

Left behind in Europe was Sylvia Demb's brother, Julius, who apparently couldn't get his immigration papers and was left behind to fend for himself. Oral tradition reports the harrowing experience he had getting out of Poland. He and his friend walked away from Mlynov with essentially nothing on their backs and after several days of travel found an abandoned building to sleep in overnight. Julius's friend was sleeping on the ground floor while he slept on the second floor. When Julius awoke in the morning, he found his friend with his throat slit, apparently from a robbery during the night. He had been lucky on the second floor.[31] Somehow, Julius made his way out of Poland to Buenos Aires, where he ended up with other Mlynov boys there, including David (aka "Sonny/Sam") Goldseker, who also had a harrowing story of escape.

Sonny Goldseker took leave of his family about this same time. His mother had passed away in 1914 near the outbreak of the War. He was about twenty at the time when he said goodbye in an emotional farewell to his father whom he would never see again. His daughter Audrey tells the story of his harrowing journey. He first made his way to Buenos Aires before heading to the United States, where he joined his siblings Ida (Goldseker) Gresser and Morris Goldseker, who emigrated before the War. His sister, Eta, who had mothered him in Mlynov after his mother died, subsequently left Mlynov in 1924 for Palestine to marry David Fishman, who made aliyah in 1921 with the Fishman family in a story recounted previously. Sonny's brother, Chuna, followed him to Buenos Aires, fell in love and stayed there, which happened to at least one other Mlynov boy, as we shall now see.[32]

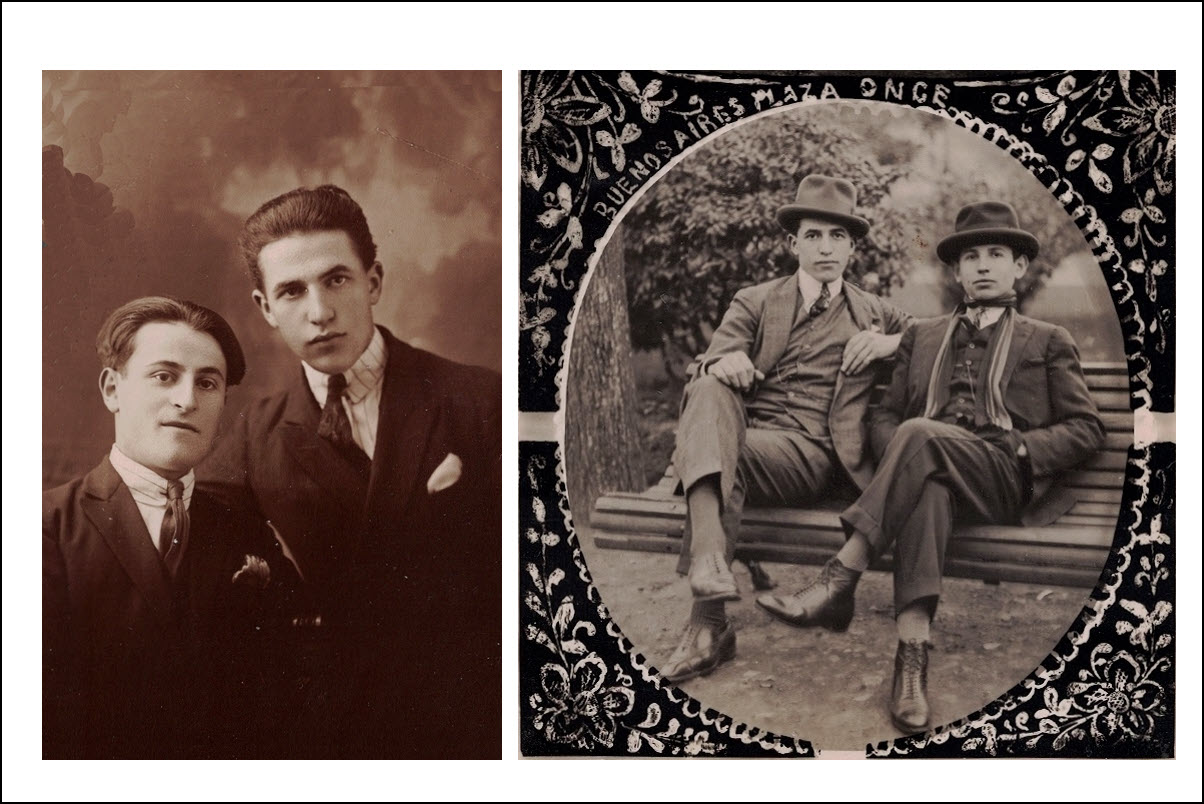

There were other Mlynov boys in Buenos Aires at the same time as became apparent from a photo that "Sonny" Goldseker saved from his time there.[34] Later in Baltimore, when talking about the photo with his daughter, Audrey, he remembered his friends only by their nicknames which he reported as: Muttle, Etool, Woodluck, Woodluck's brother. Some were simply "unknown." Subsequent research established the identities of several of those friends. They were all Mlynov boys trying to get into the US to join family in a period when immigration quotas had significantly tightened for East European immigrants.

"Etool" turned out to be Julius Deming from the Mlynov Demb family. He was trying to rejoin the rest of his family in the US. "Woodluck" turned out to be the way Sonny pronounced "Wulach," the family name of another Mlynov family. Woodluck was "Morris (Moshe Aron) Wallace" and "Woodluck's brother" was Isidore (Isaac) Wallace. They were both on their way to join their father Jacob Wallace (Jankel Wulach) who immigrated in 1913 with the Berger family to Chicago. Father and sons had been separated during WWI. Their brother, Nahum (Nathan) Wulach, also went to Argentina but fell in love there and never made it to the States.[33] One of the unknown persons in the photo turned to be Karl Berger from the Berger family on his way to join his family in Chicago.

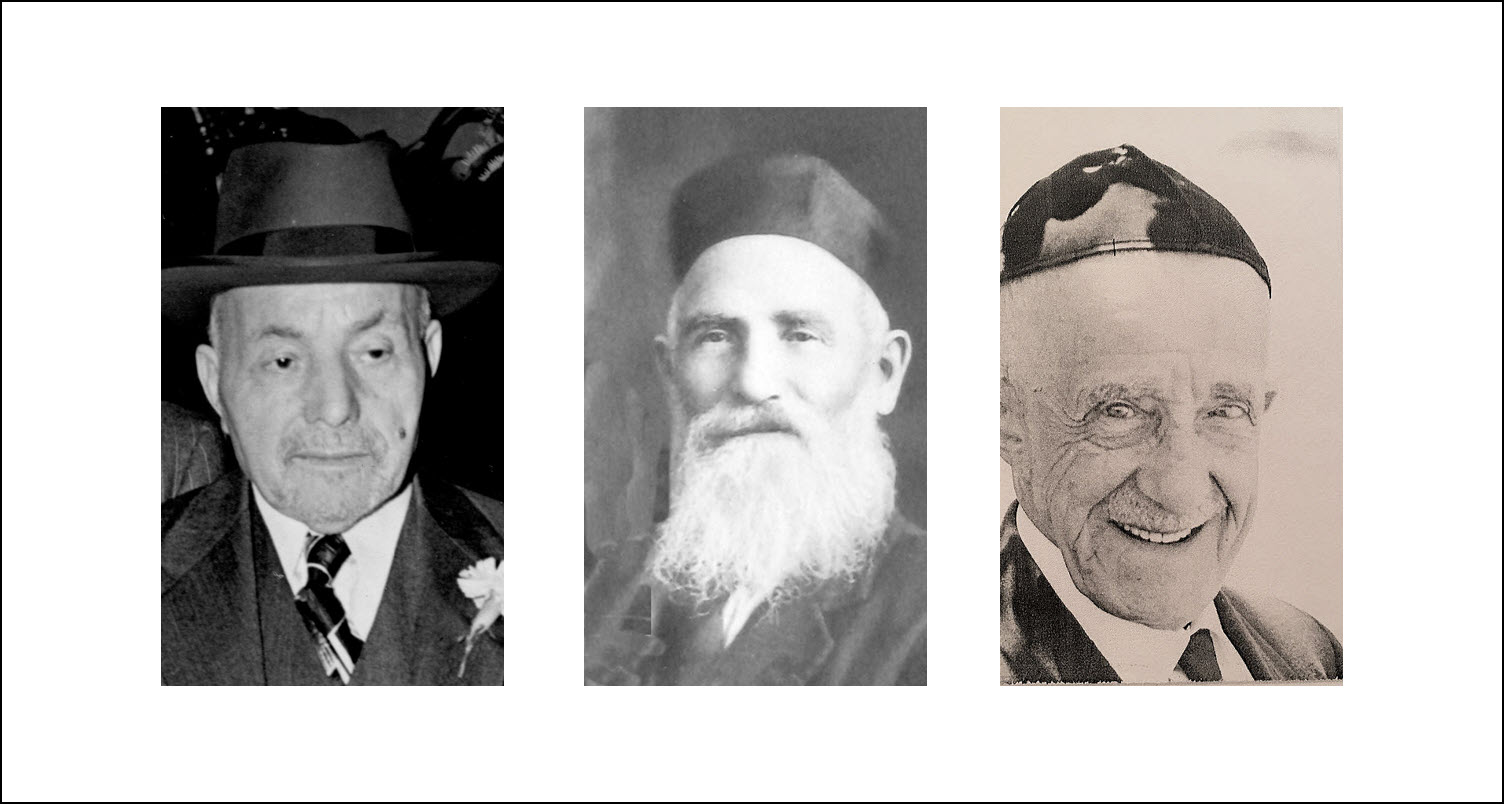

Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires (left to right) (photo on left) Muttle's brother, Muttle Meizlish; (photo on right): Sam Goldseker and Muttle Meizlish. Courtesy of Audrey Goldeker Polt.

Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires (left to right) (photo on left) Muttle's brother, Muttle Meizlish; (photo on right): Sam Goldseker and Muttle Meizlish. Courtesy of Audrey Goldeker Polt. Sam Goldseker with Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires 1924. Remembered by their nicknames. (back row left to right): Samuel Goldseker, Woodluck [=Morris Wallace], Unknown [=Karl Berger]; (front row) Muttle, Woodluck's brother [=Isidore Wallace], Etool [=Julius Deming]. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt.

Sam Goldseker with Mlynov friends in Buenos Aires 1924. Remembered by their nicknames. (back row left to right): Samuel Goldseker, Woodluck [=Morris Wallace], Unknown [=Karl Berger]; (front row) Muttle, Woodluck's brother [=Isidore Wallace], Etool [=Julius Deming]. Courtesy of Audrey Goldseker Polt.All the Mlynov boys who passed through Argentina on their way to the States had to use various forms of obfuscations to circumvent US customs, some pretending to be Spanish born, one pretending to be Dutch (Julius Deming) and one taking the identity of his brother (Frank Settleman). It is clear that a number of them knew and supported each other while in Buenos Aires together. It is also seems likely there are some Mlynov descendants probably still in Argentina that perhaps sometime we will learn about.

Jump back to the top.

***

The Path Through Mexico

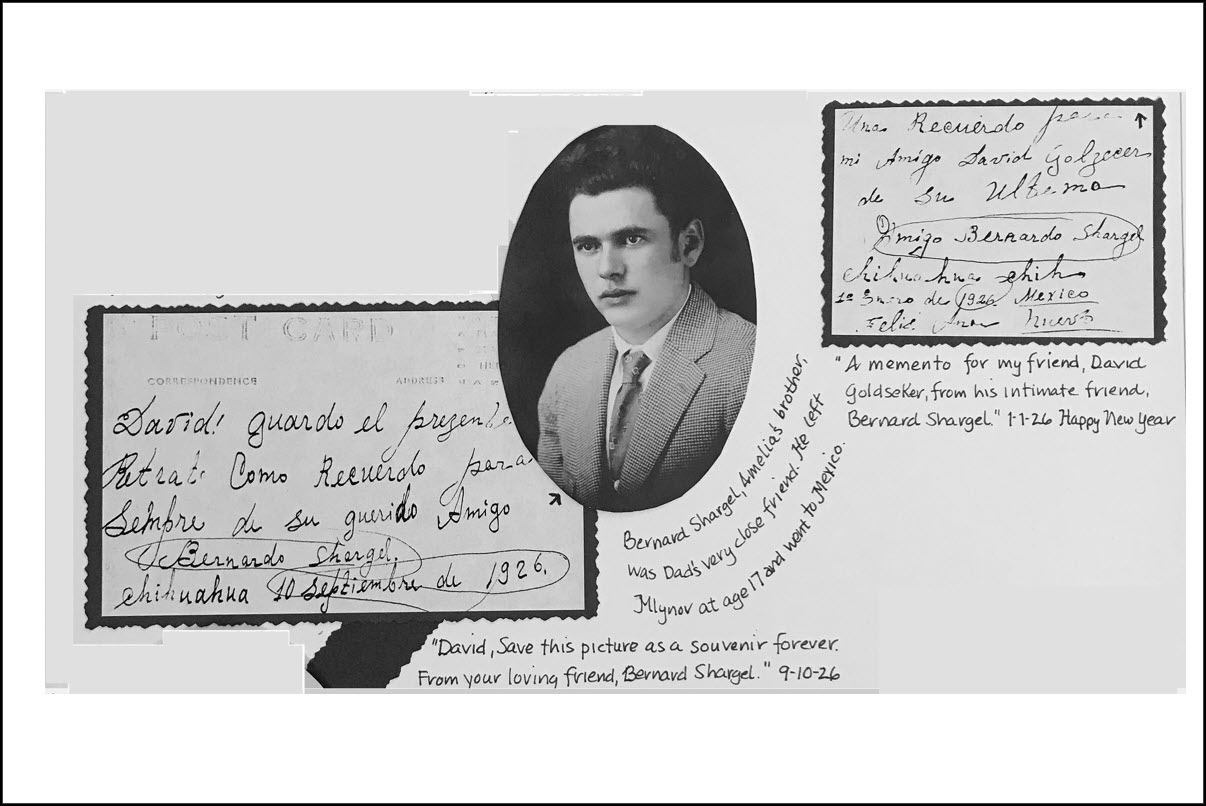

The Shargel family from Mlynov also split up at this time to try to get to Baltimore. Two of the older Shargel children, Mollie and Itzhik (Julius) had in fact already gone to the US before the War in 1909 and 1911 and had lived for a while in New York before migrating to Baltimore. Now that the War was over, the rest of their family wanted to join them. Sonny Goldseker, a close friend of Bernard Shargel, recounted the story to his daughter:

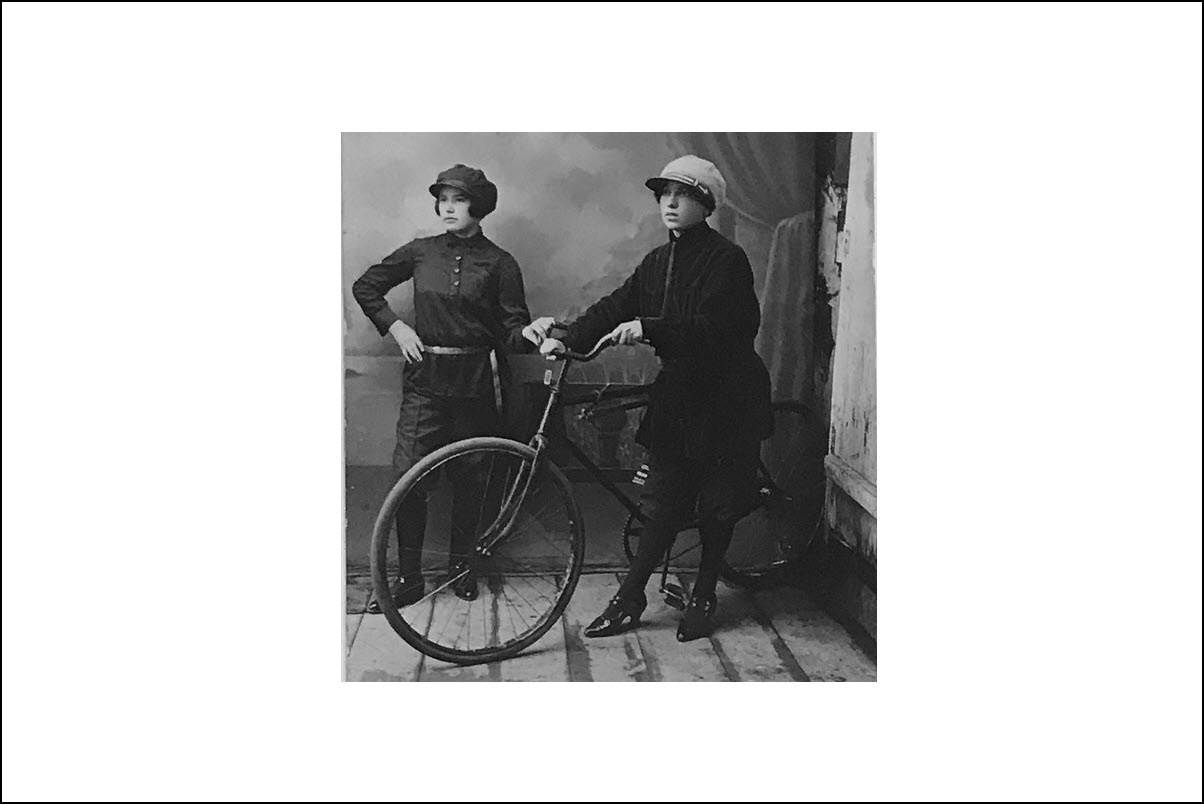

In 1926, at the age of 14, Amelia Shargel and her younger brother, Earl, moved into a rented room in Shimon Goldseker's house in Mlynov. Their parents immigrated to America in hopes of bringing the children later. [During] December 1926, they left Mlynov and joined their two older brothers in Mexico, Yizkah (Isaac) and Bernard. Amelia, Earl and Bernard joined their parents in America in 1929 (The picture postcard to the left, taken in Mlynov was sent] [by Bernard Shargel]to Dad [Sonny Goldseker] in Argentina. Amelia is with Dad's sister Charna [Goldseker].[35]

Amelia and Earl entered the United States in 1929. Amelia's Declaration of Intention from 1934 says she emigrated to the US from Chihuaha (or Chechahua) Mexico on the C.P.E. Railroad and arrived at the port of El Paso, Texas on Feb. 5, 1929.

Amelia and Earl Shargel were among the last Mlynov immigrants to arrive in United States in the third wave of immigration. A few others would make it in before WWII through the efforts among the earlier Mlynov immigrants to Baltimore. Amelia Shargel, for example, who entered in 1929 via Mexico, mounted an effort to bring Baruch Meren to the States in 1939 and subsequently married him. Most of the other immigrants to Baltimore would be survivors of WWII, and their stories are told next.

***

Notes