LANOVTSY, UKRAINE

Alternate names: Lanovtsy [Ukr], Łanowce [Pol], Lanovtse, Lanavtse, Lanivtsy Region: Volhynia

— 49°52' / 26°05' —

A Call from Our Ancestors: Return to Lonovitz - continued from page 2

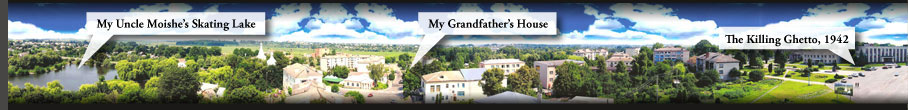

Boomi: Ask Stepan if the Jews were taken from their own homes to a ghetto for some time before the massacre occurred? (Stepan looks at the map from the Lonovitz Yizkor Book.) Alex: Something is wrong with the map. It is not quite correct. Stepan says that the people from the houses shown on his map were all moved to the center of Lonovitz, where the ghetto had been established. The ghetto was fenced in and had small houses within. Current County Administration Building and parking lot is where the ghetto was located in the early ’40s.

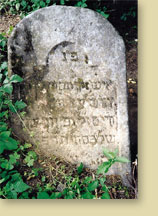

Figure 5 – A headstone from a grave in the Jewish cemetery. Vol. 14, #3, 2006 East European Genealogical Society Spring 2006 East European Genealogist ... 15

Boomi: Just as it appears in the black-and-white picture we brought. Alex: I asked Stepan if any of the Jewish homes still exist. Stepan says “no.” All were destroyed

and disassembled. In the period of time between when the Germans left and when the Soviets arrived, there was anarchy here. There were many robberies. The thieves would even take apart houses for use in building barns outside of the village. Boomi: Years ago, on my fi rst trip to Buenos Aires, Argentina, there were some survivors from Lonovitz living there. One of them old me that two of our cousins (I don’t know which cousins) had come back to Lonovitz after the war. People had moved into their home. When they tried to get their houses back, the inhabitants came and killed them. That’s what we were told. Sol: …in 1945, 1946…? Alex: Stepan says he didn’t know about this, but it could have happened. Stepan says he was not here then. He says this probably happened before the Soviets came, during that period of anarchy. There were gangs here. The Soviets came in March, 1944. And the Jewish houses were here until then.

Stepan told us he was back in Lonovitz by 1953. He saw major construction work going on in the town. The old houses were destroyed, new houses and apartment buildings were being built. Further discussion dealt with what happened to the houses the Jews lived in prior to being taken to the ghetto area. What happened to the belongings of each house? Stepan surmises that the houses stood and Ukrainians moved therein, until the Russians arrived. Whatever was in the houses were used or taken by others. He also surmises that the KGB took some jewelry for themselves. We showed Stepan and his son, Grigory, family pictures taken during the 20s and 30s of Chizda/Karner family members; he did not recognize anyone. Finally, we all left the Mission, andwalked to the street where our grandparents lived. Only one house still stood from the days of our family on the “residential side” of the street. This was the Brimmer house. Across the street where the businesses were (i.e., our grandfather’s blacksmith shop) is now a huge Russian-built apartment complex.

Figure 6 – "The chilling thing for us was that across the street from the former ghetto area stands a building they identified as the Gestapo headquarters.

Figure 6 – "The chilling thing for us was that across the street from the former ghetto area stands a building they identified as the Gestapo headquarters. That building is still in use today" Vol. 14, #3, 2006 ...10 East European Genealogist Spring 2006

October 9, 2002 – Last Visit to Lonovitz

After leaving Vishnivitz, we stopped in Lonovitz to visit the Jewish Cemetery and Massacre Site one last time. When we arrived, there were three young boys and one girl, approximately, 11-13 years old, playing with a soccer ball on the massacre site. There were hitting the “Eeta” gravestone in the center of the site. Alex got out of the car and reamed these children out. They walked away and waited until we left. Upon looking back as we drove away, we saw these kids go right back to what they were doing. We also stopped at the Horyn River in Lonovitz. Moishe, our father’s younger brother, drowned in the Horyn at about the age of 12. Fetter Chaim Silverman went into the water and brought Moishe back to his parents’ home to be readied for burial.

October 9, 2002 – Back in L’viv

When we arrived in L’viv, I don’t remember whether the Hotel Grand did not have a “room at the Inn,” or if we asked Alex if there was a nice hotel close by that would cost less. He suggested the George Hotel, a couple of blocks from the Grand. So we spent our last nights in L’viv at the George Hotel. Maybe not as fancy, but quite comfortable and it was less expensive.

Thursday, October 10th, 2002

Our first stop on this day of sightseeing was a return to the synagogue on Mykhnovskykh Street. This time a tiny 90-year-old congregant, Naftaly Cheppel, came out to greet us. I interviewed him and listened to his sad story. He was also “acting” Rabbi of the synagogue; the Rabbi was in vacation in Israel. We also met Meylekh Sheykhet, who works for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage and Advocacy of Jews in the Ukraine area. He told me that before becoming involved with the above-mentioned program, he was a telecommunications expert. He was a scientist and lecturer, and when Soviet Russia “died,” he was very happy and started a new phase in his life. He gave up everything he had done and involved himself in Preservation, because it needs a lot of skills. It is a very hard job because of the terrible destruction of archives and all evidence of Jewish history. “We have to fi nd it piece by piece, little by little, from different parts of the world, from different archives to put it together and preserve Jewish Heritage.” He was able to renovate and preserve many holy sites of Jewish people in the Ukraine such as building Ohels (chapels) for learned ancestors and fencing in the cemeteries. He works with the American Commission for the Preservation of Heritage. Sol and I then entered the synagogue. Prayers either had not begun or there was a lull for a few moments while we visited. We were able to take pictures of the interior of this old and beautiful synagogue, the only one left of seventeen that had once been in L’viv. Some twenty men were gathered for morning prayers. Most had talaysim (prayer shawls), and, of course, keepahs (head coverings). The walls of the synagogue had wonderful colorful depictions on various parts of the wall. The interior of the synagogue was currently under repair.

We then continued touring L’viv with Alex. He took us to various places of Jewish interest. “Filler’s Passage,” which Alex said was a “smart street,” was at one time owned by a wealthy Jewish merchant. The fi rst fl oor of his buildings were his shops; the second and third fl oors were leased

Next, we were taken to the “Old Market Square,” the center of the town in the 14th century. Alex took us to a place in that area where there had been a reform synagogue for the progressive community. The synagogue was built in 1844-45; it was destroyed by the Nazis in July 1941.

Alex then brought us to the former site of the Great Synagogue of the Krakov suburb, which housed a school of Torah studies. It was built in the 17th century, and rebuilt in the 19th century. This synagogue was blown up by the Nazis in August 1941. The total population of L’viv before World War II was about 200,000; over 60,000 were Jews; about 30% of the population. The Jewish population was a bit larger in the early 1900s, and a bit smaller when World War II began.

We then were taken to the former entrance to the Jewish Ghetto during World War II. Alex showed us the memorial with a plaque erected to “The People Who Perished in the Ghetto.” The memorial was built in 1992-93, after Ukraine become independent. This is a very important place; this ghetto was huge. From it people were sent to other concentration camps: to Treblinka, to Auschwitz, but most were sent to Belzets (Bełżec).

Alex then drove to the massacre site in L’viv where people from the Yaniv concentration camp were buried. This camp is not as famous as others, but over 200,000 Jews died there. The area in which this site is located still belongs to a governmental institution built in Soviet times, the Ministry of Internal Affairs. They train dogs here, and no visitors are allowed to see the massacre site, in back of the compound. The people in the camp were buried in mass graves, but also, these mass graves were “burnt down.” Gentiles who lived in the very distant sections of L’viv still remember the strong smell of the burnt bodies, which they recognized right away because of the distinctive smell of burning human fl esh. For years people from the community have approached the authorities—fi rst, the Soviets, and since 1991, the Ukrainian government—about moving their dog-training program elsewhere. The answer was always, “We will move somewhere, but we need a location to move to.” It’s like a vicious circle. Alex is sure this was done on purpose in Soviet times. He thinks it is terrible to train dogs here. Maybe someday the Ukrainian government will find the money or the will to move the dogs away from the massacre site. continued...

![]()

page 3 of 4 << previous page | next page >>