LANOVTSY, UKRAINE

Alternate names: Lanovtsy [Ukr], Łanowce [Pol], Lanovtse, Lanavtse, Lanivtsy Region: Volhynia

— 49°52' / 26°05' —

A Call from Our Ancestors: Return to Lonovitz - Boomi Silverman

Boomi Silverman, a native of Winnipeg, moved to the United States in the mid-50s. She has worked in various fields, including broadcasting, marketing, and currently property management. She became interested in genealogy while visiting relatives in Winnipeg in 1991, and began sending data sheets to family members to gain background knowledge. This culminated in the fi rst family reunion in Detroit in 1995, attended by relatives from Canada, the United States, England, Israel and Australia. Boomi has been a member of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Michigan since 1996, and currently serves as their Vice President of Publicity. In October 2002 Boomi and her cousin, Sol Sylvan, traveled to Ukraine and Poland to visit their village and fi nd out what happened to their grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. This article is based on her experiences.

At one time there were 17 synagogues in L’viv; onlytwo still exist. One operates as an Orthodox synagogue.The other, a former Chasidic synagogue, isnow a Jewish Cultural Community Center. When we were fi nished touring this section of L’viv, we walked back towards the Grand Hotel. In front of the hotel there is a plaza where a goodly number of people were milling around. A monument to the Ukrainian National Poet Shevchenko is located there. This plaza is like the speaker’s corner in Hyde Park, London, England—an area where people come to talk of political subjects and topics. In the evening some people gather here to sing. Alex pointed out the Amadeus, a good restaurant he recommended for supper that evening. The Amadeus only has seating for some 30 guests and features a large choice of items. For entertainment they had a jazz clarinetist and a keyboard artist. These two “artists” were great! After the meal, we took a walk around the area and returned to the hotel. We were both exhausted, as we hadn’t really slept for almost two days!

Monday, October 7, 2002

While waiting for Alex to arrive for our second scheduled tour day of L’viv, Sol suggested that instead of staying in L’viv for two nights, we should go today to our ancestral shtetl (village), Lonovitz.* I agreed. When Alex came to pick us, we told him

October 5-6, 2002

I met my cousin, Sol Sylvan, of Issaquah, Washington, at the Newark, New Jersey airport in order to board the Polish LOT Airline, which took us to Warsaw. We arrived on the 6th. From Warsaw, a smaller plane took us to L’viv, Ukraine. Upon arrival in L’viv, it took some time to get all the

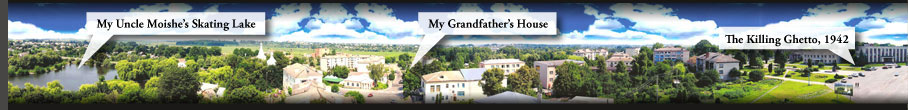

Lonovitz was located in the Volynia District of Poland. Today, it is in the Ukraine. Jews probably settled there after 1569 when municipal charters were granted under the Polish King. The Jewish population numbered 1,174 in 1897, or 46% of the 2,525 total population. It shrunk to 649 in 1921 after a series of pogroms and disturbances. A school operated alongside a small Yeshiva (school), and the Zionists with their youth movements were active. Sporadic killing and forced labor under brutal Ukrainian guards accompanied the German occupation from July 3, 1941. In the Aktion, which liquidated the ghetto on August 13-14, 1942, 1,933 Jews including refugees were murdered beside open pits.—The Encylopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust, ed. Schmuel Spector, Geoffrey Wigoder.

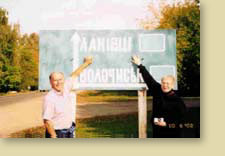

Figure 1 – A signpost for Lonovitz(Lanivtsi) East European Genealogical Society Vol. 14, #3, 2006 ...10 East European Genealogist Spring 2006

*Editor’s Note—also called Lanovitz, in Yiddish Lanovtsi, in Polish Łanowce, in Russian Лановцы (Lanovtsy), and in Ukrainian Ланівці (Lanivtsi). Vol. 14, #3, 2006 East European Genealogical Society Spring 2006 East European Genealogist ... 9

of our decision. He left us to return to his home and get his traveling bag together. While he did this, we enjoyed a delicious buffet breakfast at the Grand Hotel. We checked out of the hotel upon Alex’s return, and then, together with our baggage, got into Alex’s station wagon, and off we drove off—we thought, for Lonovitz.

Instead, Alex took us to the only operating synagogue in L’viv, on Mykhnovskykh Street. We entered the synagogue “compound” through a gate. There was a small courtyard between the synagogue and a community building holding school rooms, meeting rooms, a kitchen and restroom. From the synagogue came a gentleman wearing a tallis (prayer shawl) and keepah (head covering). He greeted us, told us that the congregation was praying currently, and we could not go into the synagogue at this time. We took some pictures in the synagogue courtyard, and told the gentleman we were off to visit our ancestral shtetls, but would return to the synagogue at the end of the week.

Łanowce – Lonovitz – Lanovtsy

We drove through L’viv to the highway that would bring us to Lonovitz. On the outskirts of L’viv, we noted new and large housing “subdivisions” being built. We were to see this type of building going up at other shtetls and cities during our trip. The drive to Lonovitz was interesting. The two-lane asphalt highway roads were not bad at all. Traffic was relatively sparse. We saw many two-horse wagons fi lled with sugar beets, along with a modest amount of vehicular traffi c. At times, there was a pony attached to the horse mother’s binding, making it a three-horse wagon. Most of the area we drove through was farmland. Families or workers were still working in the fi elds, collecting sugar beets. Except for where sugar beets were being pulled from the earth, most of the farmland had already been tilled. When Alex pointed out the fi rst of the several signs we were to see before hitting the outskirts of Lonovitz, we stopped at practically every one and took pictures, as for instance in Figure 1. You want to talk about getting excited? We were getting close to what had always been a “mythical black and white picture” of our shtetl. Now we were going to see the real place where our parents, my elder brother, grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, had been born and lived. Those members of the family who had remained in Lonovitz perished.

We learned quickly that when Alex entered the outskirts of a shtetl that he had never visited before, he stopped the fi rst pedestrian he came across and asked directions to the Jewish cemetery and/or massacre site. In most cases, he was told exactly how to get to these sites. We also noticed that as the person who was giving us instructions was still talking, Alex would say “Thank you,” roll up his window, and leave the person, literally, in the dust! Later, when asked why he did this, Alex said he didn’t want to waste any time getting to places that we needed to see!

When we arrived at the Lonovitz massacre and cemetery site, and saw what was there, Sol and I were completely overwhelmed (see Figure 2). What we first saw was a partially enclosed brick/concrete outer fence surrounding twin mounds of earth separated by a sidewalk. The twin mounds were in the shape of triangles. Just before one enters the sidewalk area, there stands a tall, thin rectangular obelisk, with a woman’s crying face surrounded by an oval frame a third of the way from the top. Underneath the face is a square brass sign with a Hebrew inscription. Under it a sign in Ukrainian says, “Inhabitants of Lanivtsi area, to the Victims of the Nazis.” There was a basket of plastic fl owers in front of the obelisk.

Directly behind the obelisk was a concrete sidewalk approximately three-four feet wide and over thirty feet long, covered with chalked graffi ti, obviously put there by children. On the left and right sides of the sidewalk were two long pyramid-shaped mounds of earth covered in grass. (On a second trip to Lonovitz in June 2003, Sol and his wife, Katherine, measured the site. Facing the entrance, the left mound is 15’ wide and 90’ long; the right mound is 15’ wide and 52’ feet long.)

At the end of the massacre site’s concrete sidewalk was a gravestone, for a woman who died in 1981. Alex translated the Ukrainian inscription on the stone. It read “Eeta Nucheemovna” (daughter of Nucheem). Alex said the last name on the tombstone read “Onishinkov.” We learned later that Eeta had been the last Jew to die in Lonovitz. From her last name, Alex commented that her husband must have been Ukrainian. (We have been unable to learn why Eeta was buried on the massacre site instead of in the old cemetery next to it.) We then went into the adjacent old Jewish cemetery. We were greeted by two tethered goats (see Figure 3). We were shocked by this, but after walking through the cemetery and seeing that the outer regions were overgrown, we understood why the goats were there: they kept the front part of the cemetery “mowed.” There was also trash, old car tires, rusted items, etc in the cemetery. We could not discern where any of our forebears were buried. Most of the inscriptions were old and faded. None of the tombstones that I could read had a surname engraved on it; Jews in Ukraine did not have last names until the late 18th century. Tombstones from that era only had patronymic names; i. e., “Mechel, son of Moshe,” or, “Sarah, daughter of Laibel,” and so on. The years listed on the tombstones were in Hebrew letters; I could not decipher them. We stayed at both cemeteries for some time, taking pictures. continued...

![]()

page 1 of 4 next page >>