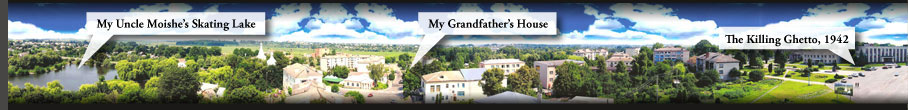

LANOVTSY, UKRAINE

Alternate names: Lanovtsy [Ukr], Łanowce [Pol], Lanovtse, Lanavtse, Lanivtsy Region: Volhynia

— 49°52' / 26°05' —

A Call from Our Ancestors: Return to Lonovitz - continued from page 1

Before our trip began, I made sure I had the Kaddish(mourner’s prayer) with me in both Hebrew and English, so that I could say the prayer in Hebrew, and another for Sol, in English. Sol had not thought to bring a keepah, nor did I. It was Alex who loaned Sol his keepah so that he could read the Kaddish. Alex always has one with him and wears it at religious sites and cemeteries, out of respect to the Jews who had died and for our religion. Sol and I recited the Kaddish in front of the massacre site, for our dead but not forgotten family members, and all other Lonivitzers who perished there.

Figure 2 – The massacre site at Lonovitz.

Vol. 14, #3, 2006 East European Genealogical Society Spring 2006 East European Genealogist ... 11

Just before getting into the car, Sol asked Alex about the possibility of locating a current map of Lonovitz. The only one we had was the enlarged copy of a map we both brought

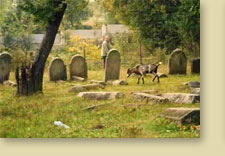

showing the Jewish section of Lonovitz prior to the war. This map identifi ed the residents who lived and worked within that area and had come from the Lonovitz Yizkor (Memorial) book. Just as we were ready to drive to the Town Hall of Lonovitz, an older woman approached us. She wore a cotton blouse, slacks, and a babushka on her head. The woman’s name was Tayina Trohymivna Onyschuck. She was the granddaughter of the old Lonovitz Jewish Cemetery caretaker, Tzisaruk Oleksandr. She told us that she and her husband try to keep the cemetery grounds in good order, but it is diffi cult to do because of vandalism and the trash that is dumped there.

Tayina told us of the method the Nazis had used to commit the massacre in Lonovitz. She said that when Nazis came and were ready to begin their holocaust, they told the Gentile inhabitants residing around the Jewish cemetery to leave the area and go to the other

side of the village. This was done so they would not be able to see (or hear) what would be happening at the cemetery.

Tayina was also aware that books were sometimes buried in the Jewish cemetery. She had no idea why because no one actually saw the books being buried. She had been told this was some kind of secret. She did not know until we told her that when Jewish books, religious or otherwise, became torn or tattered or damaged, they were not destroyed, but, instead, buried just like people, out of respect.

We told Tayina that we would be coming back to Lonovitz the next day. She promised she would stop by. Unfortunately, we did not ask which house she lived in. When we returned to the massacre and cemetery site on the two following days, we looked for her, but she never came back to where we had met her the fi rst day.

We then left the cemetery area and drove into Lonovitz itself. Again, Alex stopped someone to ask where the Town Hall was, and in a few minutes we were there. Alex needed a map of the village. He also hoped that someone at the village could tell him something of the town, and perhaps direct him to the oldest inhabitants, who might remember the Jewish community. Unfortunately, the map they had was too large for our use.

When Alex and Sol came out of the Town Hall, a gentleman approached them. He was the Vice- Mayor of Lonovitz. He tried to help us with the current plan plan of the town, but could not; he was not a local. He had come from the Khmel’nyts’kyi area, and had held his position for just a short time. The Vice-Mayor recommended we go to the County Administration Building, not far away, which had an architectural department and town archives.

It took only a minute or two to get to the County Administration Building. We were directed to an offi ce on the third fl oor. A receptionist greeted us; she called the head of the Archives to come to her office. An older woman arrived within a minute or two, and when asked about maps, etc., she told us she had none. She left the offi ce and told other officials about our interests.

Figure 3 –The cemetery’s “mowers.”

East European Genealogical Society Vol. 14, #3, 2006 ...12 East European Genealogist Spring 2006

The Mission was located on the corner of a street, in a nondescript two-story building, which obviously had been something else previously. We met its pastor, Vladimir Androshuk, who appeared to be approximately 35 years old. He was very soft-spoken and extremely helpful. He is married and he and his wife have two young children. Vladimir told us that in 1993 he had visited Israel. He was interested in the history of the area. The mission had established a small museum here.

In 1942, according to Vladimir, 3,500 Jews perished in Lonovitz. In 1999, his congregants realized that the massacre site was in very poor shape. They brought people there to clean and fi x it up and take care of it. It was the local Lonovitzers who participated in the “forgiveness ceremony.” It was a special occasion to tell Jewish people that the current Ukrainian generation was very sorry that the Ukrainian people collaborated with the Nazis during the war. Since that date, 1999, other generations of local inhabitants would know and have the confi dence that they wouldn’t be blamed for what was carried out by former generations, and that they would be “forgiven.” Androshuk invited Jews in nearby local communities, along with people in Kiev and Ternopil. They, too, gathered at the massacre site upon the date the “forgiveness cemetery” was held. Vladimir next mentioned “the maps”; he asked someone to bring them to us. In a few moments they appeared; both were sizable, one larger than the other. These maps were handwritten on white cardboard; the smaller one was not in good repair. Words were written in the Cyrillic alphabet. Vladimir explained that a man named Basiuk “made the maps by himself, with his own hands.” They show the location of Jewish businesses and houses, synagogues, including Rabbis’ houses, the names of the owners of the houses in 1939. Both Sol and I were absolutely stunned—our grandfather and other relatives lived in Lonovitz at that time! Vladimir called Mr. Basiuk, the man who drew these maps, and an appointment was scheduled for 10 a.m. the next day at the Mission.

We drove to Ternipol and checked into the Ternopil Hotel, where we were to spend two nights. The lighting throughout the hotel was not being “overused.” The building obviously dated to circa 1940-1950, during the Soviet occupation.

October 8, 2002 – 10:00 a.m.

When we arrived in Lonovitz to meet with the creator of the “Jewish Map,” the “map drawer,” Stepan Kupriyanovitz Basiuk, had brought along his son, Grigory Basiuk. Here is a transcript of our conversation: Alex: Stepan has a photograph where all the students are together; Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians are on the picture. They are fi rst grade to 11 years old.

Boomi: Ask Stepan if in those years the boys had shaved heads? I remember my parents had such a Lonovitz school picture.

Vol. 14, #3, 2006 East European Genealogical Society. Spring 2006 East European Genealogist ... 13

Stepan: It was a normal thing. They wouldn’t shave the heads, but the boys all had short haircuts. Maybe some guys had lice and they had to havetheir heads shaved. My mother was a very clean woman. She always gave me clean clothing. I kept my jacket or coat separate from the other children when in school. [I had brought along a large black-and-white photo of Lonovitz taken in the 1920s or 30s, and pictures of the Chizdas, my paternal ancestors (the family name was changed to Silverman in Winnipeg) and Karners (my maternal ancestors) from the same time frame. I showed it to Stepan. He pointed to a sign at the bottom right corner of the photo (see Figure 4)]: Stepan: This is interesting. The person who was the owner of the wholesale storage of beer and whose advertisement is here on the picture you brought, his name is Brimmer. His son studied with me at school.

The son survived the war. During the beginning of World War II, when the Soviets came, the son was also in business/trade. For some reason, it was considered a fi nancial crime in those days to be involved in private enterprise. Brimmer’s son was imprisoned and sent to Siberia. That is how he survived the war. After the war, Mr. Brimmer came back to Lonovitz.\ He was the one that surrounded the massacre site with a fence and marked the place where the mass graves are located. After he accomplished that, he moved to Israel. In August, 1942, the Nazis told the local people to dig deep pits next to the Jewish cemetery. The people were not told why they had to make these pits, and no one would ask the question. Other people would come with their horses and wagons and take away the removed soil from the pits. This is the place Jews were murdered and buried.

Figure 4 – Stepan (seated) compares his maps to the old photos of Lonovitz

for Alex (standing). East European Genealogical Society Vol. 14, #3, 2006

... 14 East European Genealogist Spring 2006

![]()

page 2 of 4 << previous page | next page >>