|

|

Kežmarok, Slovakia |

|

|

Kežmarok, Slovakia |

On this page:

The following material was adapted, with kind permission, from the historian Dr. Nora BARATHOVA, who has published several books. She conducted extensive research by reading issues of old newspapers dating as far back as 1865, to glean information about the life and times of Jewish people in Kezmarok, and some distinct personalities. Mikulas LIPTAK performed an initial rough translation into English and Madeleine ISENBERG, together with Miki, edited the material. The following is an extract from some of that research combined with information from additional sources, such as the manuscripts of Nathan VENETZIANER.

In the early part of the 19th Century, Jews were not originally allowed to even live in Kezmarok. Jews did live in Huncovce, a town that was only five kilometers away, and were able to ply their trades by traveling to Kezmarok during the day time. But they were required to leave the town by nightfall to return home to sleep.

However, when Kezmarok became a "royal free town" in the mid 1850s then they could actually live there. At this beginning of settlement, there were so few Jews, that they did not even have their own religious organization; they still belonged to the community in Huncovce. The Jewish religious community (Kehillah) came into existence in Kezmarok only in 1852, with 19 members. At its head was the merchant Salomon Wolf ROTH (1819 – 1884), descended probably from a merchant family in Huncovce /7/.

The Jewish registry district of Kezmarok belonged to Huncovce, where recording of the vital records began in 1833; but recording of information from Kezmarok began only in 1852/8/.

The community was so small community that at first they built a small structure on a piece of purchased land that was behind the town walls and not far from the wooden Protestant church. It was sufficient for the Jewish worshippers to gather there on Saturdays and the Jewish holidays. They did not have their own local rabbi, so they shared the rabbi who commuted from Huncovce. Even though it was considered only a small prayer room, in 1865 the newspaper Zipser Anzeiger referred to it as a synagogue.

Nathan VENETZIANER, who was among

the first residents, held many positions in the town: He was a shochet

(ritual slaughterer), a mohel (circumciser), a scribe, an historian, and

a deputy rabbi. He was probably the first person to enter information

into registry records for the life events that took place in Kezmarok,

starting in 1858.

His manuscript (Manuscript number, MS9617 /15/) written in Hebrew, detailing the

history of Jewish Kezmarok and the construction of its first synagogue, "Adas Yeshurun," resides in the Special Collections Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, in New York City. This manuscript provided invaluable information regarding how the Jewish community came

to be established and the building of its first place of worship

(1854-1858). A copy of the manuscript was purchased, transcribed into

a digital format by Hagit TSAFRIRI and translated by Madeleine ISENBERG and Hagit, over a period of months in 2009-2010 /9/.

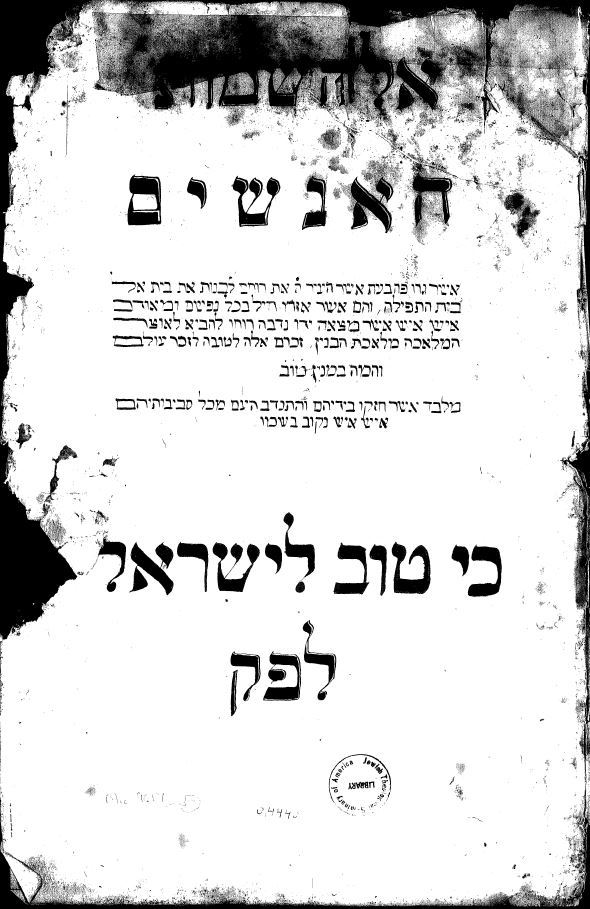

First Page of MS91617 |

The copy purchased from the library was in black and white (as shown at left). Information was

requested on the colors in the original. This provided the

opportunity to simulate the decorations in both Hebrew and English versions. Click on the little icons to see and read the The people whose names are mentioned in the document, aside from King Ferdinand I of Austro-Hungary (aka Ferdinand V of Bohemia), are (at right): |

|

With the Jewish community growing fast, in 1874 the Jews from Kezmarok invited their first rabbi, Abraham GRÜNBURG (1839 – 1918) from Miskolc, to become their rabbi.

|

|

|

His son, Rabbi Noson Simcha and grandson, Rabbi Meir, stayed in Kezmarok as well, becoming a small rabbinic dynasty there until World War II. (Rabbi Meir Grünberg survived the war and eventually emigrated to the USA.)/14/

|

Painting by Pavel Wavrek of the Great Synagogue, Adas Yeshurun, based on a black and white photograph. |

Rendering of the Synagogue plan, as found in the book by E. Barkany-L. Dojc, Zidovské nábozenské obce na Slovensku (1991), |

Similar to Interior of the |

Similar to Interior of the |

A year later, in 1882 the synagogue was consecrated. (Surprisingly, there was no mention of this event in the local weekly newspaper Karpathen-Post.) The synagogue was built in the Moorish style, like the ones still existent in Prešov (shown here) and Michalovce, with dimensions of 22m x 15m. Just behind the main door was an anteroom. On both sides, there were doors to stairways leading to the women's balcony. The women were separated from men, who entered and sat on the ground floor level. The women could watch the services through the decorative railing from above. Jews are supposed to face eastward, as if facing Jerusalem. So the Aron Hakodesh (the Holy Ark that housed the Torah scrolls) was situated at the eastern end of the synagogue, on the ground floor. The Ark was covered with a decorative curtain, and on either side there were seats for the rabbi, cantor and the head of the Jewish congregation. In the center of the synagogue was an elevated platform (a bima) with a reader’s table for the reading/chanting the Torah portions. or for the person delivering the sermon /10/. The choir was led by the cantor SCHREIBER, who led services beginning in the 1890s /11/.

After World War II the synagogue was used as a storehouse until 1961, when under the Communist regime, it was demolished to construct the road to Levoca. In addition to the synagogue, other facilities were necessary for routine Jewish life and practices. The Jewish bakery where bread the matzoth (unleavened bread for the holiday of Passover) were prepared was near the synagogue. The Bet-Hamidrash (the room of prayers and also the social and administrative center) was built next door to the synagogue or the bakery as well. Unfortunately, neither of these buildings exists today.The mikvah, or ritual bath, was opened on the 15th of December 1890. The director of the autonomous Orthodox Jewish religious community posted a competition for the construction of the mikvah. The baths were accessible to the general public as well. It was supposed to be one of the most modern ones in the country. Of course, the public steam and tub baths were strictly separated from the ritual one. It is interesting to note that at the time of its opening the renter was not a Jew, but rather the Christian, Samuel HORVAY. In 1898 the baths were renovated to form three distinct sections: changing rooms in one part; a swimming pool and showers in the second; and tub baths in the third /12/. Today (2007), a laundry exists at this site.

View of the Kezmarok Cemetery at time of Cleanup by Astra Fellowship

In the 21st Century,

Judaism has adherents who practice the religion and follow the

guidelines of the Torah and the rabbis in many different ways. In the

18th Century, an offshoot of Orthodox Judaism developed called

Chassidism that advocated more emotional aspects of prayer and serving

the Lord with joy and songs. Chasidism was practiced by the majority of

Jews in the Ukraine, Galicia, and central Poland. Chassidism also spread

into the eastern part of Slovakia, with its limiting border in

Kežmarok. They were, and still are, recognized

by their distinctive dress.

In Kezmarok, a separate place of prayer was built for the Chassidim, specifically for Rabbi Aryeh Leib HALBERSTAMM and his followers.

Rabbi Halberstamm was known as the "Mushene Rebbe," having served as the chief rabbi of Muszyna, Poland, prior to coming to Kezmarok. His congregation, smaller than that of Rabbi GRÜNBERG, was known as a kloiz. While the building no longer exists, there is photo of the interior taken by Yitzchak RIMPLER of New York on a visit to Kezmarok, in 1983. It was destroyed by the Communists. Another personality in Kezmarok, was Rabbi Israel Meir GLÜCK, who headed the Talmud Society.

Rabbi Halberstamm was known as the "Mushene Rebbe," having served as the chief rabbi of Muszyna, Poland, prior to coming to Kezmarok. His congregation, smaller than that of Rabbi GRÜNBERG, was known as a kloiz. While the building no longer exists, there is photo of the interior taken by Yitzchak RIMPLER of New York on a visit to Kezmarok, in 1983. It was destroyed by the Communists. Another personality in Kezmarok, was Rabbi Israel Meir GLÜCK, who headed the Talmud Society.

In summary, there were three types of congregations, i.e. the Orthodox, Chassidic and Neologistic.

Kežmarok was not

significantly different from other Jewish communities – because there

were two large groups that sometimes had conflicts. Even though (on

November 15,1881) the Neologists and Orthodox Jewish congregations

merged into one with a common prayer service in the prayer hall, the

conflicts continued for decades, as can be seen in the article in the

Karpathen-Post newspaper written by David ZINN, a sergeant in the

Emperor’s 38th Honvéd battalion. He complained about the leader of the

Orthodox Jewish group: “When I came to the synagogue to pray on the 29th

September 1884 on Rosh Hashanah (the New Year), I took a seat which was

neither labeled as a designated seat, nor paid for use on the High

Holidays. While sitting there, Mr. B. GLÜCKSMANN came up to me and said:

“Get out of this place. It is Eduard KOHN’s (GLÜCKSMANN’s nephew)

seat and he will be paying for that.”

I replied immediately that I would pay as much as is necessary as well.

Without saying a word he called two local soldiers who, on behalf of the

town's mayor, asked me to leave the synagogue. After obeying these

officials and escorted by the soldiers, I went to the mayor where I

learned that neither he nor anyone else had given such an order. It was

all GLÜCKSMANN’s doing. It is really sad that in the 19th

century, in a Jewish congregation such as Kežmarok’s, that such a

distinguished person is so mean-spirited on one of the holiest days of

the year. I then left for Huncovce to pray there in their synagogue.“

It appears that GLÜCKSMANN belonged to the Orthodox Jews and ZINN

was Reform. (The conflicts between the two groups in Kežmarok ended by

the definite victory of the Neologists in December 1929 /13/).

The following week, B. GLÜCKSMANN submitted his own version of the events.

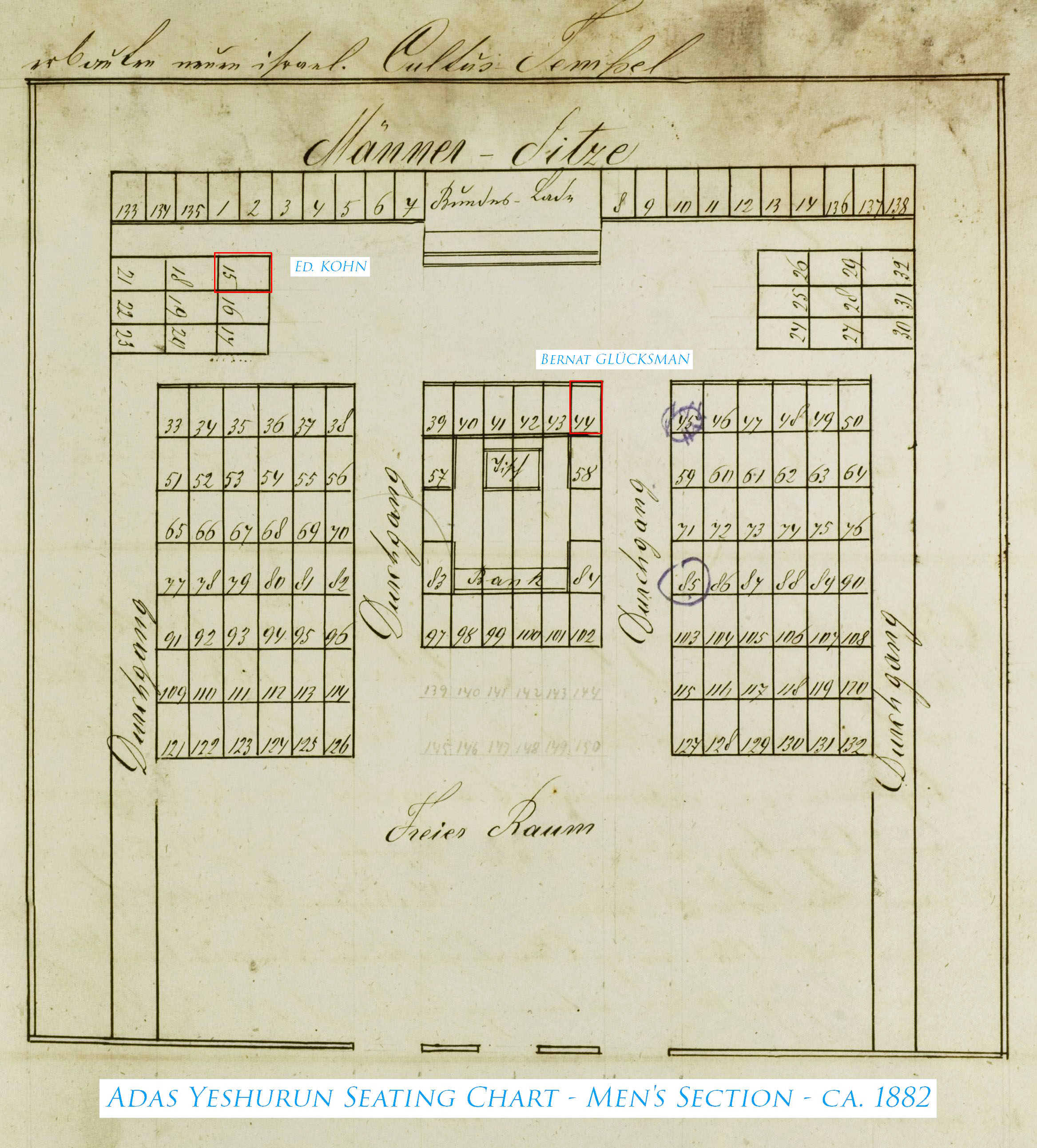

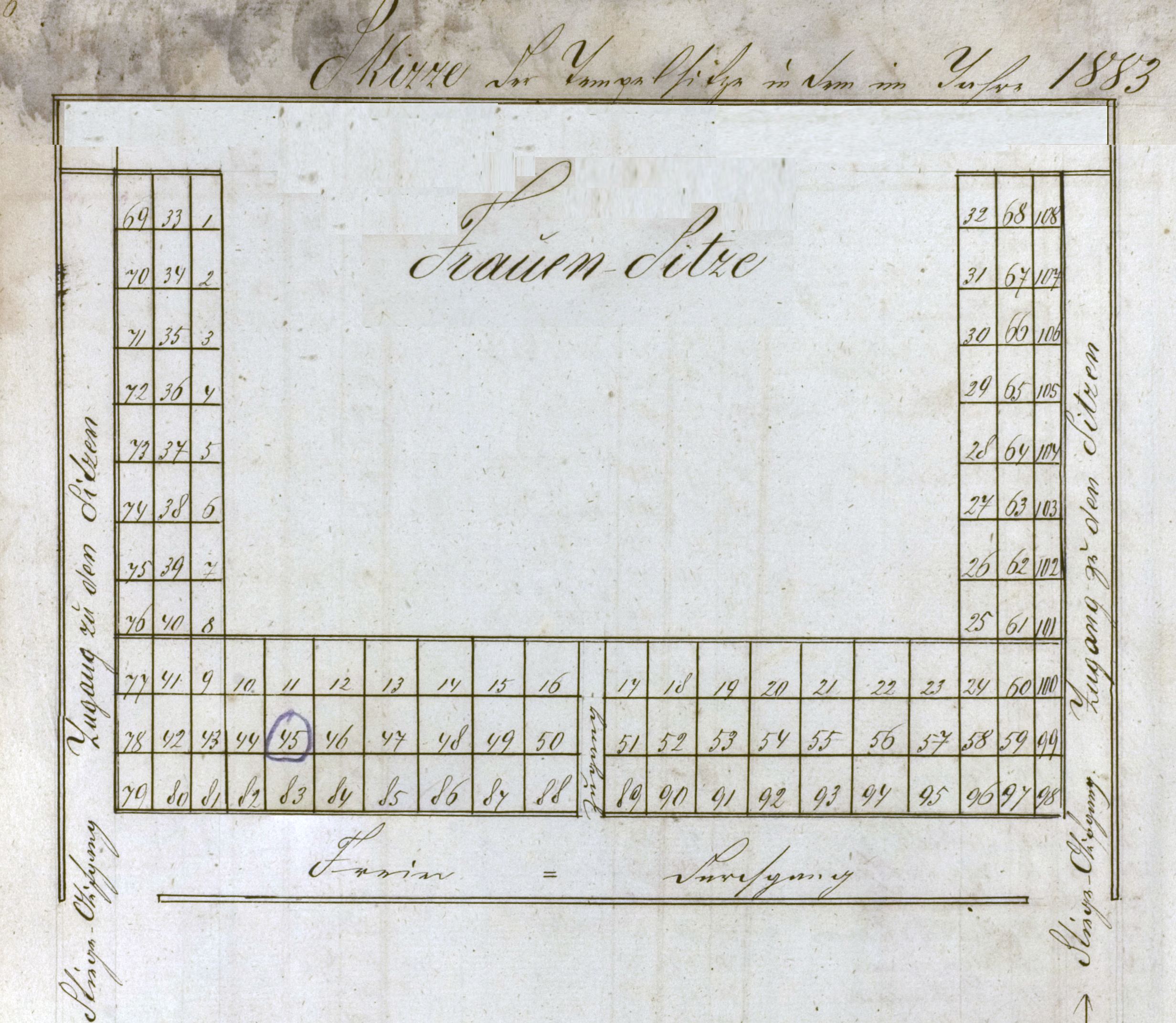

Webmaster's addendum: From the second

manuscript (MS10387, see endnote 15 below) maintained by scribe Nathan Venetzianer, High Holiday

seating charts were found. That for men as originally graphed in 1882,

just two years before the above event occurred, is shown, with that of the women just below it.

Even today, people who are regular attendees of a synagogue, generally

keep the seats from year to year that they originally selected and paid

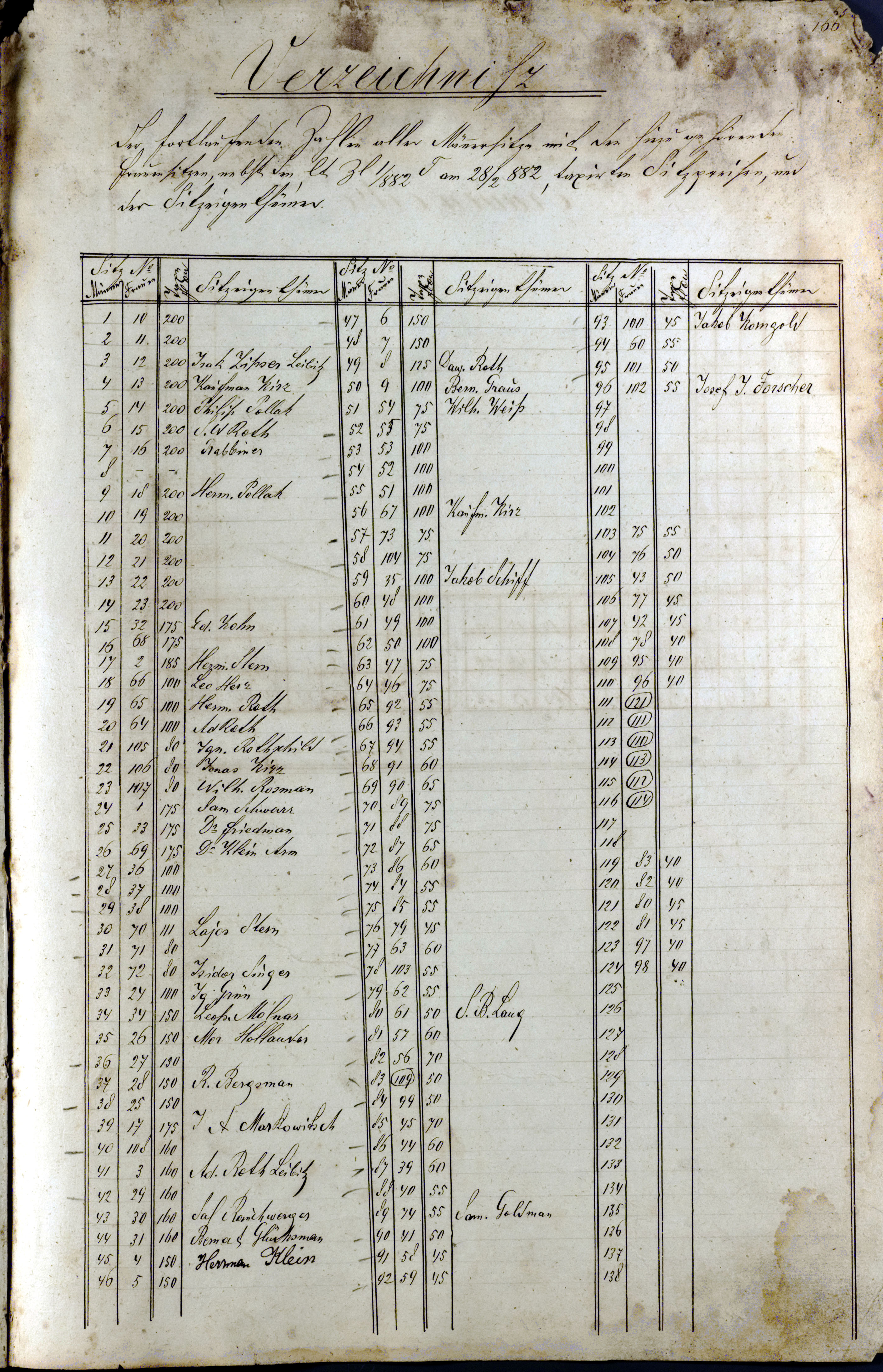

for. By careful examination of the list of member's names (found

on another page of the manuscript), I was able to determine just where

the "important people," such B. GLÜCKSMANN and Eduard KOHN sat,

and I have indicated those positions. Position "7," next to the Aron Hakodesh (Holy Ark) is designated as the Rabbi's seat.

Generally, a visitor

at such a time, not having made any previous arrangements, should have

taken an

empty seat probably toward the back of the synagogue, not right up

front. Note the large "Freier Raum" at the back, where additional

seats could have been added. Looking at this drawing, one might

conclude that David ZINN, marched up to the front, probably in front of the rabbi, and deliberately

intended to cause a disturbance.

The list on the right is the list with the men's names. There are three columns to the left of the names indicating their seat numbers; then the seat number for their wives; and most probably how much they donated for the yearly membership, possibly with higher amounts for the more desirable seats.

|

|

Notes:

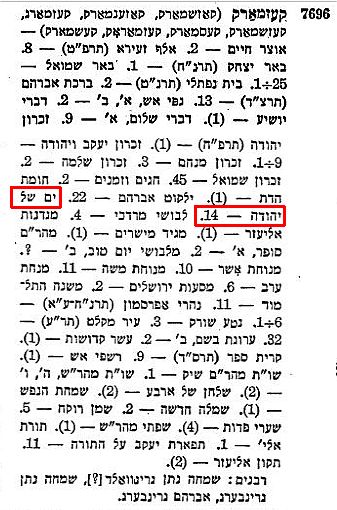

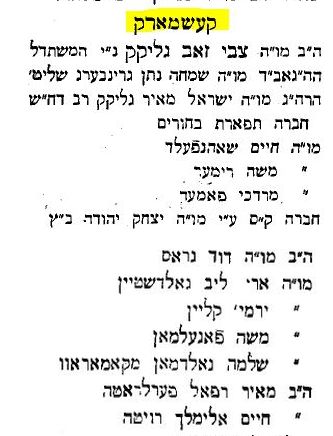

prenumeranten for Kezmarok (code 7696).

Altman's book. |

An interesting source of information are prenumeranten. These are people who paid early subscriptions to Jewish scholarly texts. So if you had studied in a yeshiva (Jewish seminary) and knew or recognized the great rabbis and scholars of the day, you would be interested in acquiring and reading what these erudite people had written -- mostly in Hebrew but occasionally in Yiddish. Hence, these pre-subscriptions to help pay for the publication of such works.

HebrewBooks.org (Type in "HebrewBooks.org" on URL line) has a wealth of

such books that have been digitized and can be searched for titles or

names of authors as well as providing the opportunity to download the

entire books in PDF format. Generally at the ends of such books, the author

would show his appreciation for the people who had subscribed and would

include their names under the heading of the respective towns where they

lived. To help in identifying which books to even check for these in Sefer Prenumeranten (On URL line, type in HebrewBooks.org/46561), Berel Kagan (or Cohen) compiled a wonderful compendium of 800 towns

and the books that have prenumeranten for these towns. His book is

also available for searching or downloading on HebrewBooks.org. The book's title in English is "Hebrew

Subscription Lists." (For more information on prenumeranten, JewishGen has an infofile, prenumeranten)

|

After World War II, and the eventual immagration of those who returned from the concentration camps, the Great Synagogue fell into disuse. In an e-mail of 25 Mar 2010, to Mr. Jack FRIEDMANN of New York, descendant of the distinguished Rabbi Israel Meir GLÜCK, Mr. Lubomir VYVLEK of Kezmarok, wrote

"... The synagogue used to stand near the New Evangelical Church and the Wooden Evangelical Chruch. The Jewish sanctuary was break down in the year 1961. After the WWII in 1945, there was ca. 100 persons of Jewish origin living in Kezmarok the rest of Jewish population (ca 1100 in 1938) was transported to the death camps in nowadays Poland. Many Jews emigrated to the State of Israel after 1948 after the establishment of Isreael and after the Communist coup d'etat in Czechoslovakia.Thus, in fact the Jewish community was destroyed in Kezmarok and the building of the synagogue was in decay. The atheist regime of the Communist Czechoslovakia did not support the religious symbols and it had actually adversary attitude towards the religions in the state. So, the synagogue was decided to be broken down and it was unfortunately done so in 1961.

The Town of Kezmarok would like to display a honor to all the Jews of Kezmarok and to the victims of the Shoa. Mr. Sajtlava will commit himself in this question. We will search the possibilities and resources to place a monument on the past holy Jewish ground.

Yours truly,

Lubomir Vyvlek

Municipality of Kezmarok, Slovakia

Dep. of Regional Development and Tourism"

Here is a photo, shortly before the synagogue was torn down to make way for a road to Levoca.

The last days of Kezmarok's Great Synagogue.

Thanks are due to Mikulas LIPTAK (of Kezmarok) and Mr. Ze'ev RAPHAEL (of Haifa) for versions of this photo.

Based on various photographs, Mordechai Wieder (of Petach Tikva, Israel) constructed a wooden model of the synagogue and it is on display in the House of Testimony (Beit Haedut) in Nir Galim, Israel.

|

Side View |

Front View |

Back View |

A very similar model was commissioned by the descendents of Kezmarok families living in Israel and brought as an addition to that part of the Kezmarok Museum dedicated to its Jewish history, by Freddie and Aliska (née GOLDMANN) WEISFEILER in 2008 (photo below).

Slightly different model in Kezmarok's Museum.

Thanks are due to Hagit TSAFRIRI, of Rechovot, ISRAEL, who took the photographs of the models.

Ze'ev RAPHAEL in Haifa sent copies of the Synagogue photos to his sister-in-law, Helen (née BRODY) Grossman, who lives in Canada. She responded to him with her first-hand memories of the synagogue.

From: Helene Grossman

To: Zeev Raphael

Sent: Friday, 11 June, 2010

Dear Zeev,

Thank you for the Kezmarok synagogue. The wooden model from photographs by Mr. Wavrek brought back memories: sitting next to my mother; sometimes near my grandmother.

There were curtains in the women section upstairs. The Chazan SINGER bacsi had a beautiful voice and we visited him often on Shabbes afternoon. He was a distant relative to our grandmother. His wife was best friend of our grandmother. They had no children and adopted 2 boys and one girl from a poor relative and sent them to school and yeshivot. Mr. Singer had a beautiful voice and we enjoyed his singing on our visits to their home. The Rabbi in the synagogue was Rav Grunberg; his sermons were in German.

A son survived, hiding with his wife, as partisans.

It's amazing how strong we can be when we have to.

Love from Leo & Hella

Updated 8 July 2022

Copyright © 2010-2022

Madeleine R. Isenberg

All rights reserved.

|

||||||

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.