|

|

Huncovce, Slovakia |

|

|

Huncovce, Slovakia |

There are many things that could be included in this website and more will be added over time. To start, this is the story of what a young boy in Huncovce, non-Jewish, experienced in May 1942, as he watched what was happening to his good neighbors.

Emil SCHNECK's story appeared in the original Slovak, in the 2006 book on Huncovce, entitled, Huncovce v zrkadle casu (Huncovce in the Mirror of Time) by Vladimír Labuda. I am grateful to Miss Monika Jasova for translating it into English and helping me edit it into a story that we will find trully touching.

Huncovce used to be the Jewish center of the Spiš region with a big synagogue and a yeshiva where rabbis were educated, and just outside of the town, an old cemetery near the river Poprad as well as a new larger cemetery. So the village of Huncovce was home to many Jewish families. Beginning in 1941 our fellow citizens, our Jewish neighbors had to wear the yellow patch with the Star of David and the inscription “Jew” under it.

Two sisters named Roth managed a store with a variety of local goods. They brought milk to my parents every evening. One of the sisters, Miss Linka Roth, was especially pleasant and kind to us – the children, my sister Gertrud and me. When we saw her coming we would run to meet her; she always had some candies for us. It was always something special for us when she brought us matzos, the unleavened bread (that Jewish people use for Passover).

In September 1941 I became a second year pupil, so that our school day extended into the afternoon. One day at the end of May 1942, our teacher, Mr. Boss, told us during lunchtime,

“Children, this afternoon you won’t have classes, so you can stay at home.”

I came home and when I told my Mom she just remained silent in fear. In the afternoon I was playing with Tibor Kvassay and Edi Bruschinský. Tibor was two years older than me and he knew why we had to stay at home. Our Jewish neighbors were ordered to gather in the park that was close to the Evangelical Church. Tibor persuaded both of us to go with him. The three of us entered the park through the gate next to the church. We encountered a devastating sight: We saw our Jewish neighbors who had hurriedly (without much time for thought) packed their most necessary things, partly into suitcases, mostly into bags and even stuffed into pillow cases. On the left side of the park I found Miss Linka with her sister and I approached them.

“Where are you going? Why do you want to leave?” I asked.

Miss Linka answered, “We don’t want to go away, but we have to.” And in the next breath she said to Edi and me, “Boys, you must go away from here. It is very dangerous for you to be here.”

Tibor ran off and went down to the where the fuel pump was located, as he told us later. At that moment military vehicles arrived. The gate to the church was closed off and guarded. Only the gate to the street was open. Edi and I wanted to get out, but we could not. Miss Linka saw our problem and shouted,

“The boys don’t belong to us!”

“Anyone could say that,” I heard someone say. Linka Roth replied, “Nevertheless, he’s still Martin’s son.”

So they set us free and from the distance, but fearfully, we watched what was happening from the other side of the street.

After the deportation of our Jewish neighbors an atmosphere of a deep shock, helplessness and fear formed in our village. Only a very few Jews were able to escape the deportation or be spared it. My grandfather, Samuel Haitsch, had a workshop that became a place of many worried conversations between him and his customers and acquaintances. They all had a common topic: We, the inhabitants of the Spiš region, will pay for this great injustice.

My grandfather used to take me to ROTH’s store, the store neighboring on uncle Unger’s house – where they both – my grandfather and uncle Unger discussed the situation with tears in their eyes. Uncle Unger said many times.

“It was a black day in the history of Huncovce and we were helpless against such an action.”

The scene of all that happened in the park, deportation of our fellow citizens and the atmosphere that followed are engraved in my memory. I use every opportunity to talk about the terrible injustice of that time, to remind the younger generation, to prevent and make it impossible for an event like this to ever happen again.

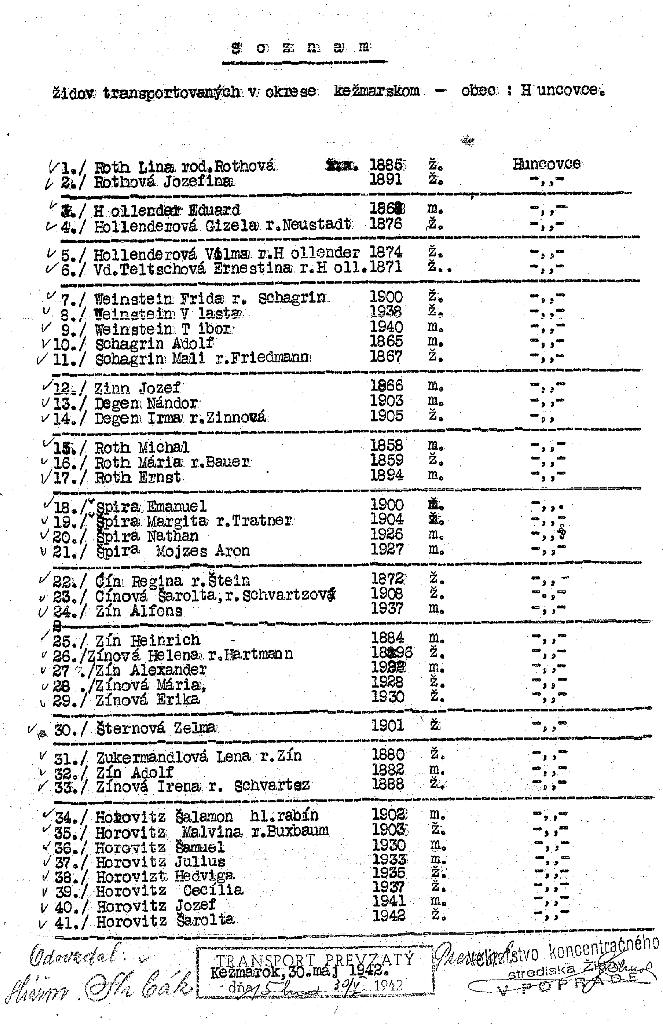

Note: The official the list of the deportation of our fellow citizens, our Jewish neighbors, to the transit camp in the town of Poprad (30th May 1942) is in the section below.

Most people check the Yad Vashem Holocaust Database for specific pages of testimony for those who were killed during WW II. However, there is another site -- in the Yad Vashem archives -- that has documents, some of which can be viewed on line. Checking in Shoah-Related Lists Database this list of 41 people was found. This is the first page of the document, followed by additional pages with a list of people from other nearby places, primarily Kezmarok. It is titled,

Jews transported in the Kežmarok district - Huncovce community

Deportation of Huncovce's Jews to the Poprad Transit Camp, 30 May 1942

Created 19 April 2012

updated 28 February 2019

Copyright © 2012-2019

Madeleine R. Isenberg

All rights reserved.

|

||||||

This site is hosted at no cost by JewishGen, Inc., the Home of Jewish Genealogy. If you have been aided in your research by this site and wish to further our mission of preserving our history for future generations, your JewishGen-erosity is greatly appreciated.