The End of Shtetl Life

After more than 400 years, Jewish life is nearly extinct in the Ukrainian town of Chechelnik

By Ira Rifkin

Photographs by Craig Terkowitz

Note: This article originally published by the Baltimore Jewish Times on October 11, 1991

Thanks to Neil Rubin from the BJT for sending me the article and giving his permission to publish it here.

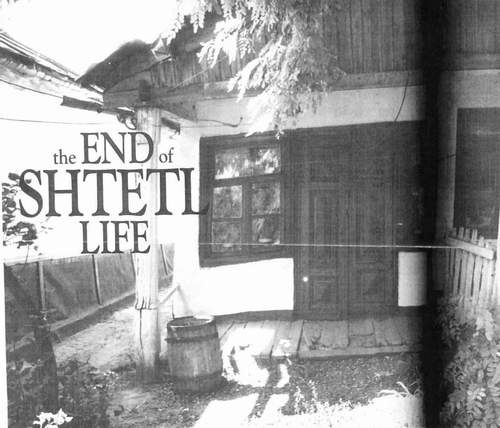

The entrance to a typical home in Chechelnik’s once-thriving Jewish town center. Despite the off-kilter appearance, this structure is in much better shape than most, and now houses a non-Jewish family.

The entrance to a typical home in Chechelnik’s once-thriving Jewish town center. Despite the off-kilter appearance, this structure is in much better shape than most, and now houses a non-Jewish family.

Chechelnik, U.S.S.R. – Sender Alexandrovic, a pry 93 and as wizened a character as one is likely to to meet, has his bags packed and is ready to emigrate to Israel.

Apart from his time in the Red Army during World War II, Mr. Alexandrovic has spent his entire life in this sleepy town of 6,000 people nestled in a small valley in the southwest Ukraine. But since his wife died four years ago, he said, life here has become too lonely to endure.

And so, he said, he will move to Israel with a grandson sometime soon.

When he does, Jewish life in Chechelnik will be a good deal closer to what seems its inevitable end.

For more than 400 years, Chechelnik was typical of the many Jewish towns or shtetlach, that dotted the western reaches of czarist Russia. Until World War II, 4,000 Jews lived in Chechelnik.

Today, however, just 30 to 40 remain, almost all of them elderly. Mr. Alexandrovic, who worked as a tailor, is the only one who still tries to observe the precepts of Jewish religious life.

In the absence of any kosher food source, Mr. Alexandrovic slaughters his own chickens. For Shabbat, he tries to visit his grandson, who lives some 30 miles away in a town with a functioning synagogue, an extremely rare occurrence in this out-of-the-way corner of the Soviet Union.

“It is hard to live here as a Jew”, Mr. Alexandrovic said in Yiddish, as he stood recently outside the dilapidated structure that has been his home for 60 years. “I sit here everyday and there’s no one to talk to.”

Anna Dorenbus, 69, and another life-long Chechelnik resident, concurred.

“To be a Jew here is to suffer. There are no people who you can talk to,” she told a group of visitors, members of a joint BALTIMORE JEWISH TIMES-Baltimore Jewish Council delegation that visited various Soviet Jewish communities in August.

If her daughter emigrates, she said, she will leave as well.

“Who would bury me?” Mrs. Dorenbus said, explaining her decision not to remain in Chechelnik.

Laughingly, she also urged her visitors to help all of Chechelnik’s Jews move to the United States. Despite her laughter, it was difficult to tell whether she was joking.

Jews first came to Chechelnik in the late 15th century, when the area was under Polish control, explained Volodya Okhs, a Jewish historian from Odessa who has spent much of the last decade documenting what little remains of Ukrainian shtetl life.

Until World War II, Jewish constituted 90 percent of the town’s population. Jewish craftsmen and merchants flourished, and a local Chasidic dynasty held sway. In all, there were ten synagogues in Chechelnik, one of which remained open until soon after “The Great Patriotic War,” as World War II is called in the Soviet Union.

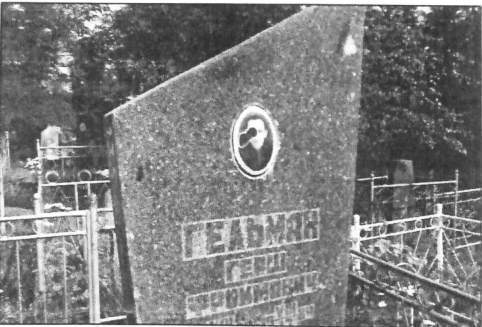

In accordance with local custom – but not Jewish tradition – contemporary Soviet Jewish gravestones often picture the deceased.

This stone was defaced by vandals.

In accordance with local custom – but not Jewish tradition – contemporary Soviet Jewish gravestones often picture the deceased.

This stone was defaced by vandals.

Formely a synagogue, this building dating from the 18th Century is now a furniture warehouse.

Relative to what happened in the neighboring Jewish towns, Chechelnik made it through the war in good shape, Mr. Okhs said. “Only a couple of hundred” Chechelnik Jews were killed by Germans and their Romanian henchmen, he said.

When the Nazis, overran the area in August 1941, Chechelnik’s Jews – men, women and children – were rounded up and brought to the town square. Local Ukrainians, said Mr. Okhs, participated in the round-up.

The Germans accused the Jews of being communists and threatened to massacre them all. But before the slaughter began, a high-level, and apparently more compassionate, German officer happened upon the scene and put a stop to it.

Local legend, Mr. Okhs said, holds that the officer argued that young children couldn’t possibly be communists.

Legend also holds that the officer was actually a Soviet partisan wearing a German uniform, a viewpoint Mr. Okhs said runs counter to his own research. Regardless, the man’s actions spared thousands of lives.

After about a month of occupation, the Germans pulled out and left Romanian fascists in charge of Chechelnik, which was included in what the Romanians called the province of Transnistria. Although confined to a town ghetto, Chechelnik’s Jews were largely spared the brutal behavior of the Romanians experienced by other Jews in the region.

Mr. Okhs’ father, for example, lost much of his family in the nearby city of Balta. Four thousand Jews, nearly a third of Balta’s Jewish population, died during the war, Mr. Okhs said.

In all, some 217,000 Jews were murdered in Transnistria, a third of them Romanian Jews transported to the region to facilitate their extermination.

But while Chechelnik’s Jews physically survived the war, the town’s Jewish flavor did not make it through what Mr. Okhs termed the heavy-handed “Sovietization” of the region that occurred after the war.

Kremlin leaders suppressed Jewish culture and religious tradition in Chechelnik, as they did everywhere in the Soviet Union. In the center of Chechelnik today, a phalanx of dour-looking concrete buildings housing local government offices stands on land that was once the heart of Jewish Chechelnik.

Communist efforts to industrialize the Ukraine also contributed to the demise of Jewish life in Chechelnik by luring – and in some cases forcing – the younger generation into the cities.

Now, death and emigration to the West and Israel is writing the final chapter for Jewish life in Chechelnik and its surrounding areas.

Still, Mr. Okhs said, those Jews still in Chechelnik “remain psychologically the shtetl Jews that Sholem Aleichem wrote about.”

Unlike big-city Jews, the historian explained, the Jews of Chechelnik still speak Yiddish among themselves, they cover their heads when they visit the town’s Jewish cemetery, and some even fast out of habit on Yom Kippur.

Sender Alexandrovic and Anna Dorenbus outside the entrance to her home.

Sender Alexandrovic and Anna Dorenbus outside the entrance to her home.

Most still live in homes, now painfully dilapidated, that date from the 19th Century and lak indoor plumbing.

Mrs. Dorenbus said she gets her water from a well nearly 200 yards up the street from her home.

Her home, like nearly all the wood and plaster structures remaining from shtetl days, is in an advanced state of deterioration. Many of the homes lean noticeably on one side. Their roofs are a patchwork of tar paper, corrugated metal, wood and pressed board. Paper and cardboard covers breaks in the windows.

Some of these old homes are now occupied by non-Jews. A few have TV antennas, but generally the structures that are now home to non-Jews are no better off than those lived in by Jews.

Still, Mr. Okhs said Chechelnik’s shtetl buildings are better preserved than those of most other southern Ukrainian towns.

Despite complaining about their loneliness, Chechelnik’s Jews do not get together on any regular basis. They live scattered throughout the town and Jewish community life has ceased to exist, except for the infrequent funeral and yahrzeit commemoration held at the town’s Jewish cemetery and led by Mr. Alexandrovic, the only one who knows the appropriate prayers.

The focus today is on getting out.

“There’s nobody left here to defend us,” said Gregory Levy, when asked why he plans on moving to San Francisco, where a daughter has already settled.

Mr. Levy said he feared that political and economic chaos in the rapidly unraveling Soviet Union would unleash a new round of anti-Semitism.

Brick construction distinguishes what was once the home of a wealthy Jewish family. The structure once had a second floor balcony.

Brick construction distinguishes what was once the home of a wealthy Jewish family. The structure once had a second floor balcony.

“Jews could be blamed and attacked. That’s the history of this nation,” the 65-year-old retired butcher said.

Mr. Levy said he is often asked by his non-Jewish neighbors when he is leaving. The question, he added, is not meant as a friendly inquiry.

On the hilly outskirts of Chechelnik, the town’s Jewish cemetery abuts fields of corn and sunflowers that stretch to the horizon. On a summer’s day, the cemetery was choked with weeds interspersed with brilliantly colored wild flowers that attracted scores of small white butterflies.

The cemetery is one of the few Jewish burial grounds still in use in this part of the Soviet Union, and because it is, Jews from a number of nearby towns and villages bring their dead here to provide them with some sort of a Jewish funeral.

Mr. Okhs said that a municipal employee is paid by those Jewish families to maintain the place. It is, he said, in much better shape than the few Jewish cemeteries that remain elsewhere in the Ukraine.

Gravestones, now largely undecipherable, date from Chechelnik’s earliest days as a Jewish community. The older the grave, the lower on the hill it sits. A few of the gravestones had rocks and pebbles sitting on them, which Mr. Okhs said had recently been placed there by visitors, in accordance with Jewish custom.

In accordance with Soviet custom, the most recent gravestones bore photo engravings of the dead, whose memory they commemorate.

There is also a gravestone dedicated to children murdered in the Holocaust, and whose final resting place is unknown.

Ironically, the cemetery is the last Jewish institution still functioning in Chechelnik, the only reminder of what once existed here.

But once Mr. Alexandrovic leaves, there will be no one here who can lead a Jewish burial service.