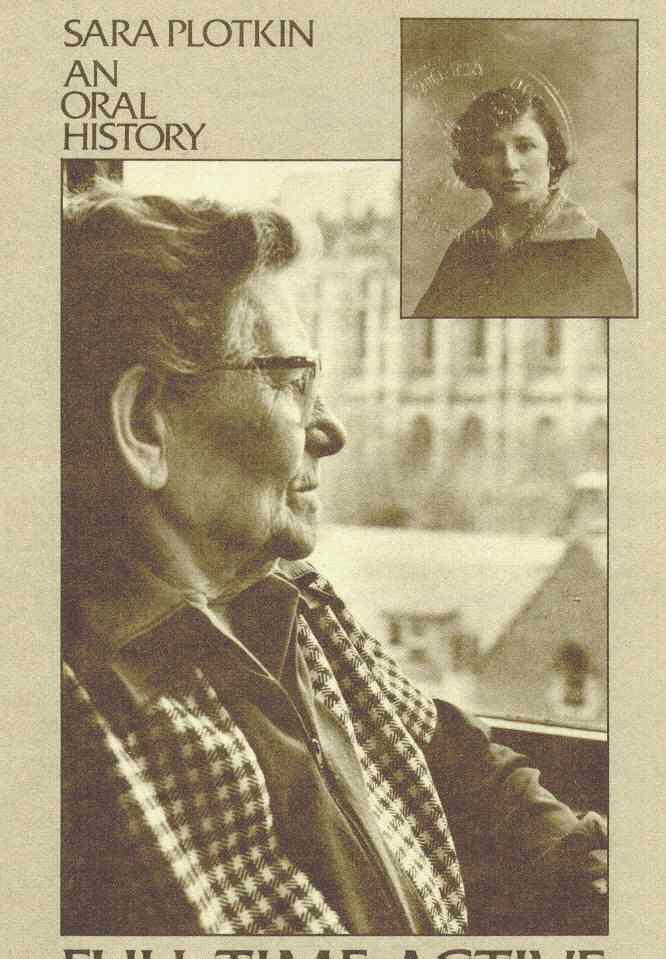

The following is an excerpt from the 35-page booklet of Sara Plotkin's life. These first three chapters recount her life as a child and as a young woman, until she left Russia in 1922.

Chapter 1

I was born in a very little town in Old Russia. The name of the place

was Schedrin. There's also a writer in Russia who has the same name. It was in

White Russia.

We were 40 miles away from one big town on one side and 40 miles away on the other side. It was about 400 miles on the way to Moscow and about 400 miles on the way to Kiev. We were a little town that had no river; we were 12 miles from a river. We didn't even have a railroad. We were 17 miles from a railroad. The transportation was by horse and buggy, but we didn't have enough money to go by horse and buggy, so we just walked. When we had to go to the big town on the way to Moscow or the other big town on the way to Kiev, we just got up early in the morning and reached there early in the evening, walking all day long.

The big towns near us had populations of 50,000, 75,000 and 100,000, and the life was a mixture of all sorts of things, but in our town most of the people were very poor. There was a carpenter, there was a shoemaker, and there was a tailor, but no one had enough to eat. Because there wasn't a market, it was very hard to make a living. Even the one who hired people to help bring in the harvest was very poor. I didn't have a pair of shoes until I was 12 years of age and for that pair of shoes I practically had to strike.

When I first started work as an 11-year-old, I brought in ten cents a day, or 60 cents a week, which was quite a contribution and I wanted a pair of shoes but I didn't dare to ask. I waited a year until just before I was 12. It was in the spring of the year. I came to my mother and said, "I want to have a pair of shoes of my own." She said, "You're not even 12 years, and you want a pair of shoes! I was engaged to be married, at the age of 17, before I got a pair of shoes of my own." But I was firm. I said if I don't get a pair of shoes, I'm not going to work. Finally, my mother gave in.

I used to go every day from work to the shoemaker to ask what was doing with my shoes. I wanted high heels, not very high, but medium heels. I wanted them to look just like the ones the big people wore and I wanted them to make noise when you walked. In the old country, when the grown-ups walked they made noise and it was very attractive. But the shoemaker kept saying in order to get you the noise, you have to put a quarter pound of sugar in the shoes. And where would I get a quarter pound of sugar? So I had to settle for shoes without the noise. It was very simple leather for workingmen's shoes, but to me it was the biggest, nicest shoes in the whole world when I got it. I used to get up in the morning to look at them. We had no thieves, there was nothing stolen, but I was afraid for my shoes. I didn't want them to disappear. I couldn't wear them every day. I wore them only on Saturday or Sunday when I went out in the evening among the other young ladies. The rest of the time I went barefoot because I couldn't afford to wear out the shoes.

Life was very, very horrible. My mother had bread and potatoes in the house - more potatoes than bread because it was cheaper - and when wanted something more my thought we were sinners. One time, we mentioned to my mother that it would be very nice to have a herring once a week. A herring cost three kopeks, or around a penny and a half and the herring was about a quarter of a pound. My mother thought that was terrible. You had to be a millionaire to buy a herring every week. Who did we think we were? She was not a millionaire, my father was not a millionaire, we couldn't afford a herring every week. And when we did get a herring, you had to divide it among 12 to 14 people. Each portion of herring was thin as a knife. And everybody wanted to have the head because the head was salty. We could eat it with a big piece of bread and a glass of tea or water. There was more to the head than a small piece of herring. So my mother invented a game, like in a lottery, and the lucky one got the head and there were no squabbles about it.

We were 11 children and my parents were two, so we were 13. I was the last in the family, the baby. My oldest brother was 25 years older than me. He was already married and out of our family when I was born. Another brother was also out. But there were still eight, nine children, and my parents, and in the old country, we always had a visitor. When you want to eat, you invited everybody who was in the house. When we had a guest, my mother managed by taking a little bit of soup from one, a little bit of soup from another, until it made an extra plate. She used to divide everything for the children, for the husband, for the guest, but she never took for herself. When I grew up a little, I insisted that she get herself as much food as we had. She worked hard and she was very thin and she didn't eat. I said, if you don't eat, I won't eat. I was very small when I was a youngster. I started to grow only after I was 17. Before I grew they used to tell me, go dance under the table, and I could have danced under the table. But when I insisted, my mother took a little soup, too. Otherwise she would just as easily make do with a piece of bread and a glass of tea without sugar. Sugar wasn't even expensive, but there was no money to buy it. We divided one small piece of sugar, no matter how many glasses of tea there were. And that was the life.

Education was just unthinkable. The Czarist government didn't allow it in our little town. When a young man who had a Ph.D. opened a school free to the children of the poor, the government closed it after two weeks. They forbid us to have a private school. The government even forbid us to have a library. Instead we had an illegal library in someone's basement, which was open only at night to change books a few times a week. The young people in town organized it and collected the money for it. They also produced workers' plays there. The charge for the library was the equivalent of five cents a month. If you pleaded poverty, they gave you the books free. I felt that the books were worth it to me, so I gave a nickel a month. It was my school.

My formal education was like this. My mother hired a teacher to teach me how to write a Jewish letter and Russian address because this was necessary. But as soon as the teacher taught me how to read and pronounce the Russian alphabet, I went on my own. I read and I kept on reading. Originally, they were very small works. But later on, I read all the classics: Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and anyone else. When I went to the library, I borrowed two or three books at a time and sat up reading them by the kerosene lamp until 3 in the morning. Even though the lamp was very small and I made a small light, my mother worried that I burned too much fuel. But that was something I had to do. My mother couldn't stop me.

This was 1906 and I was eight. Somehow we knew about the 1905 revolution. We got a little information from those who had participated, although most of those who survived never wanted to tell us anything. They were so disgusted with how things were going that a good many of them became religious, and a good many of them became cynics. They didn't believe in anything that we could do. Later on, in 1917, we read in the papers that the Czar was overthrown. I remember running to a friend's house to tell them the news, and my friend's mother asked, "So, what's going to be now?" I didn't know.

Chapter 2

My people starting going

to America about 1910, when I was 12. Even in the big towns, the poverty was great

and the oppression of the Czar was great, and there was no way to make a living.

Everybody knew that in America you could work. America was pictured as being much

more beautiful than it was. But still and all, you had a chance to work and make

a living, whatever it was. My oldest brother went first and then he took over

another one, and so on. The last one left about 1912 or 1913, leaving only my

father, mother and me. We were supposed to leave in 1914, but the first World

War broke out before we got our passports and we remained stranded.

We were a very small town. We had only two streets and on both sides of the streets for miles were fields and woods. I remember during the 1905 revolution, when speakers came from the big city, they held their meetings in the woods. I used to go there to listen, but I didn't understand what they were saying. Even in 1917, when speakers came, especially the zionists, we didn't know what they were speaking about. When didn't know who or what the proletariat was. When they said workers, we understood, but not proletariat. They spoke of the capitalist market. To me, Boboisk was a big market and Minsk a large market; we didn't understand the world market of capitalists. I remember stopping one of the speakers and telling him to speak to us so that we could understand. At one point, one of the speakers called over the organizer of the zionists and told him to try to get me in because I had a mind of my own. I spoke up. Others were ashamed, they wouldn't speak up. I didn't know and I asked questions. I didn't know what a proletariat is. I didn't know how capitalists were looking for markets. They have plenty of big markets in the city of Minsk. What were they looking for? So I told them. Why don't you speak to us so that we should understand. We don't understand you. When the Bolsheviks sent a speaker, he spoke our language. He spoke exactly the way we understood.

There were hardships and everything else, but we were young; nothing mattered. We were full of life, full of the devil, full of laughter, full of giggles. We never stopped laughing, we never stopped smiling, it was just part of us. We were surrounded by animals. Among the Jewish people there was not usually a love for animals, but we were surrounded by them. We had cows and cats and horses and little goats and they were beautiful. After a day's work, I'd go with the other youngsters - some took their horses, some took their cows, some took their cats - to a pasture, a wheat field that belonged to a rich landlord, and we brought along some potatoes and baked them on a fire and had all the fun in the world, until 4 o'clock in the morning. Then I'd come home, spend two or three hours sleeping, and go back to work.

In those days, work meant from sunrise to sunset. During the summer, the day was very long. But it didn't matter. I was doing field work, digging potatoes, planting, weeding. That was the work that was available, there was no other work available. We were children, we had our lives. When the winter started, we walked on the snow barefoot before I had my shoes. We just walked out and ran over to the next house in the snow and in the frost. My mother couldn't imagine why we laughed so much. What was there to laugh about? What was there to be happy about?

I started to grow only after I was 17 years of age. Until then I was short. But I was very attached to my work. When we dug potatoes, the rows I made were the most even. Everybody had three rows. I took care of my three rows and I didn't go ahead of the other girls. I took out and planted potatoes from one side, and I planted potatoes on the other side. Because I had to empty the baskets from all the other girls because I was fast and I only got 25 kopeks a day, even after two or three years of work; the bigger girls got 40 kopeks a day. They said I couldn't get any more because I was a little girl.

Then we had a very rainy summer. The people couldn't take potatoes out of the ground fast enough because they were afraid a freeze would come right after the rain and freeze the potatoes and the ground and the other vegetables. I knew that it was time to speak up for myself. I went to the field, but I didn't go to work. The boss saw me and said, "Well, why don't you start working?" I said, "For how much?" "Don't you know for how much?" I said, "No. No more 25 kopeks." "How much do you want"? "I want 40 kopeks, like the other girls." She said, "For crying out loud, you still wet your bed." I said, "It's not your business what I do at night, whether I wet my bed or I don't wet my bed. At present, you know that I work as much, or more, than the other girls and I want 40 kopeks." She didn't like me speaking up like that, so she let me go.

So I told myself, I'll go somewhere else and I wouldn't ask right off for 40 kopeks. I'll work for half an hour first and then I'll speak about my work. Because if I would come, a little kid, and ask for 40 kopeks, everybody would think I'm crazy. The boss was a woman. She said, "All right, I'll give you 30." Before it was 25, 30 was better, but it still wasn't equal to the others. She said, all right, I'll give you 40. I said, okay, wait a minute." I got two girls who were working nearby and told the boss to say how much she would pay me in front of the others. It was the only way to hold her to her promise.

My mother couldn't understand what I was about. She couldn't understand how, when work was slow, I didn't want to lower my price. My mother knew I wasn't lazy, so she couldn't understand why I fought so with the way things were. My mother used to say that God punished her when I became a human. But God had nothing to do with it. I was a rebel all by myself. To me that I should get 25 and the others should get 40 doing the same work wasn't logical. My father was very educated and very intelligent, but he never fought. According to the Jewish religion, he would say, you have to go by the rules and regulations of the Kihille, the congregation, of the big, rich people.

After the Czar was overthrown and all the businesses had failed, we set up a cooperative to buy and distribute food. Everybody was assessed a certain amount to help the cooperative meet expenses; the poor paid as little as 50 kopeks and the rich paid as much as five rubles. One day my father comes from synagogue with the news that they put in an assessment for us for five rubles and we couldn't afford it; we didn't have the five rubles. It meant we wouldn't be able to get flour for our bread; or the half pound of sugar we were allowed, or the half pound of salt. So I went to the cooperative myself and found the one in charge, who was very much an exploiter.

At one time, this man had been in charge of recording births and deaths in the village, and when somebody went away and then came back for the birth certificate, he made them sign over their land to him. He had accumulated hundreds of thousands of acres by this method. And he made the peasants who worked for him turn over 60 percent of their crop. For me and for all the young people, he was a hateful man.

When I got there, he asked me, "What do you want?" I said, "I came for the products." He said, "Well, your share of the assessment is five rubles." I said, "How much do you pay?" He said, "It's none of your business." I said, "It is my business, because I know if you pay five rubles then I shouldn't pay anything. But I know that you don't pay anything, so why should I pay five rubles?" He said, "In that case, you can't get anything." I put 50 kopeks and reached to scoop out flour from the barrel. He said I couldn't have it.

But I was 19 years of age and I was strong like three mules. And healthy like anything. I was five-four or five-five in my stockinged feet. So when that little Jew, that old man, started not to let me dip into that flour, I started to pound him for all my life, for all the hatred I felt for what all the people had to go through. I told him that this was only the beginning and that if he started more tricks, I would kill him. Then I weighed myself exactly 20 pounds of flour, exactly half a pound of sugar. I was foolish not to take two pounds of sugar; the exploiters go themselves so much more. But I was honest and I took only what was coming to us and went home.

The following night my father comes back from the synagogue and says that the man I beat up, Kiva Lazar, had threatened to bring a proposition before the cooperative to expel us. My father was very upset. Somebody else, another rich man, had defended what I did, and had won everyone over to my side. But my father didn't like it and my mother didn't like it. To them it was out of the ordinary that a girl dared to bet up an old man and weigh herself all the products that her family needed. To them it was unheard of.

Chapter 3

For awhile, I went to Kiev. I decided to live with a friend who had

family there in a small apartment.. I thought if the Red Army took control of

Kiev maybe I'd be able to go to school there, or do something, because in our

little town, with all the raids of the counter-revolutionaries and everything,

there was nothing. It was 1919.

There were no passenger trains, so I went on a freight train. It was a trip of some 400 miles. And since we didn't have any coal, we had to stop many times to get wood to stoke the furnace of the locomotive. Plus we were packed in like sardines.

People were coming from all over to get on the train, the movement never stopped. All of Russia seemed to be moving, and there was no schedule. You would sit and watch for the train, and wait. And when the train came, you had to climb up into this mob, and many times you couldn't climb up, it was too full in the car. If the others didn't want any more, they chased you away. But when you succeeded in climbing up and staying, you were standing.

It wasn't a question of sitting or of lying down and resting. You were standing for days and days and days. Sometimes you had to wait many days for a train and then stand many days when you got on. And you got to eat very little during the trip. You might have a piece of bread, if you brought it with you. Or sometimes the train would stop and you tried to get a few potatoes or something, but there was very little food.

In the three months I was in Kiev, I don't remember whether it was three or four times that the government changed hands. In the beginning, it was the Bolsheviks, then the counter-revolution, then the Germans, then the Poles. One army after another. Every day, they would post bulletins in Kreschatik Square about the status of the war. And every day you saw on the map that the Red Army was being chocked. It was holding on to Moscow and a few other places, but those were very small spots, and all around them on the map was black. Black was the territory with the counter-revolutionaries.

Then all of a sudden, I came into the square one morning, feeling very downhearted, and saw that it was clear for 500 miles around. The Reds had cleared the black space and were occupying territory for about 500 miles all around: big cities, small towns. The bulletin was even a few days old.

From then on, the Red Army started to clear, and clear, and clear until the whole of Russia was in the Soviet. But in the territory where our town was, it took the Red Army until 1921 to break through. White Russia was the ghetto of the Jews. It was the last big front of the war. The Whites had organized the peasants to fight the Jews and save Russia. Our town was like a no man's land.

Fifty miles from us was the border that the Red Army held. Twelve miles, on the other side, was a river that the anti-Reds occupied. Eventually, most of the young people ran off to fight with the Red Army. I couldn't go because I was assigned the job of printing and distributing subversive literature, especially that about the Bolshevik's demand for land for the peasants. We made leaflets on a press made out of gelatin, spreading the ink over and over again, 12 copies at a time. I used to hide the gelatin stamp and the ink under a board under my bed. My mother didn't understand why I didn't go away like the others, but when the Whites came to the house she put me in bed with a wet cloth around my head and told them typhus. A lot of people in the army were dying of typhus and they were afraid of getting it, so they used to leave immediately.

We knew from villages all around us that the anti-Reds were killing Jews and we were determined to put up a fight. We asked the Red Army for protection, for arms, for ammunition, but they said we had to wait for the army to break through. So we mobilized ourselves and organized a watch through the night. Our town was open all around - open fields and woods. The young people guarded the periphery and the old people watched around the houses. We had a half dozen rifles and only two worked, but we paraded throughout the day with all six rifles and we paraded with a dozen grenades. The grenades were useless too: they didn't have pins, but we paraded. At night we would shoot at figures in the dark and there was lots of confusion and panic, but we did it as best we could. There was no choice. Whenever anyone tried to raid us, they saw us with all our rifles and grenades and they left.

From 1917 to 1921, life was really very, very hard. It wasn't a question of meals, it was a question of basic needs. We got 20 pounds of flower for a month for three people. Sometimes we got a pack of matches. Sometimes we got half a pound of salt, and most of the time we didn't. It was very hard to get. It was very hard to buy.

I remember my father said to my mother once, Gittel, how about cooking two potatoes, small, little, medium-sized potatoes for a person, once a day, because we can't drag our feet any more. So, my mother says, I have only for two more days, but if I cook it in one day, what will we have for the other days. It was real starvation.

The peasants wouldn't sell their food for any money. The Soviet money didn't mean anything to them. They wanted gold, they wanted valuables, they wanted things from the house because they couldn't buy them anywhere. But we didn't have anything to sell because we were poor. The rich chazers could sell from their own homes, exchange with the peasants for food, but we didn't have anything. Even the Red Army was hungry, and the soldiers came many times to beg for bread, but many times I gave them my ration. They were barefoot, they had no clothes, they were hungry, they had with them rifles that were used in 1905 when Czarist government had a war with Japan, and these were rusty and many didn't work. They would sit in the middle of the village, firing their rifles, clearing out the barrels, and looking very blue. I wondered how in the world could these barefoot, little peasants, youngsters with rifles from 1905, fight those big armies, those new weapons, those who were well fed?

The winters were especially harsh. When it was 10 below, it was a pleasant day. When it went to 25 below, it was a problem to keep alive in a house without wood, and the wood was hard to come by. I used to go into the woods with a pushcart and haul back wood to our house and break it up into small pieces so that we could heat all the rooms. But when the anti-Reds started to kill people on the way to woods, we couldn't do that any more. At night, we had to sleep in a coat.

You couldn't get clothes, you couldn't get shoes, you couldn't get food, it was a struggle to get water. You had to get water from a deep well and carry it for a few blocks and keep it in a barrel for yourself. It was a struggle to get along. The worst part was for the older people. My father and mother couldn't take it because they were old and weak.

When the spring came, it was easier, but with the counter-revolutionaries nearby, it was still difficult to go out. I remember the counter-revolutionaries catching some members of the Red Army and making us watch their execution. They tied them to the horse's tail and galloped the horses through the town. We didn't have any paved streets. It was all rock and wood. Russian against Russian. I knew the men. They had been in our town for over two months and we had many meetings and discussions and dances. I knew them like I knew myself. But when the horses finished galloping, I couldn't recognize them.

When the war ended, my mother and father packed up and went to Warsaw to arrange passage to America and I remained behind. I didn't intend to come. But my father became sick while he was waiting for his visa and died. There was nothing left to do but help my mother finish the journey.

Summary Of The

Rest Of Sara's Account

In the rest of the book, Sara recounts her life in America. From Ellis Island, she and her mother went to stay in Philadelphia for a short time with one of her brothers, a garment worker, his dressmaker wife, and their two children. From there they went to Pittsburgh. Sara found the filth from the coal soot and the heat of the summers unbearable. She went to school and worked the late shift, seven nights a week until midnight. She left for New York a year later (~1925).

Within a year, she had been tapped by union organizers to help start a cafeteria workers strike. She continued to work as an organizer and representative, traveling throughout the country, and jailed many times. In 1932, she returned to Pittsburgh to help organize the steel workers and coal miners; the cafeteria union could no longer afford her because her bail was being set so high after so many arrests.

As bad as things were for her, she found the coal miners and steel workers, blacklisted from working from the miners strike in 1927-1928 to be worse off. Even in the Soviet Union, where she had been sent as a part of union delegation, people had "plenty of staples, like bread and cereal and potatoes, and plenty of vegetables. The only things that were expensive were meet, butter and eggs." By contrast, even working miners and steel workers were starving.

Once again, working for the union organizers meant traveling, arrests, and hiding out. Sick with an ulcer, down to 96 pounds, at community gatherings Sara wouldn't ask for milk because she knew that by doing so she would deprive children of their milk. She finally realized she could no longer work there and so returned to the city. She gradually recovered and went to work for the Workers Alliance during the Depression. There she helped workers get enough food, a place to live, work if possible, and welfare if necessary.

After the end of World War II, pre-shadowing McCarthy, the FBI started shadowing Sara. She was in California when the Rosenbergs, whom she had met before at rallies in Washington, were executed. At that point she lost interest in the party. She had joined her local party branch and "did what a party member did - which was to sell literature and to tell the workers about what the party was doing" but as the party became increasingly bureaucratic and more distant from the people, she became very critical of the organization and what it was doing. She talked to the local and central committee leaders but they backed off of confronting the problems and growing anti-Communist threat from the outside.

By the 1950s, Sara was no longer active in the party. She had joined New Frontiers as a volunteer organizer, doing community work funded by the Office of Economic Opportunity. It was during this time that she was last arrested. Sara and the other protestors felt that when the "welfare bureaucrats were holding a national conference at the Harriman Center, which is a building upstate that is owned by Columbia University&ldots;we felt that when they hold a conference on welfare, they should invite people on welfare to talk about their experiences: what they really get and what they do with it."

In 1964, Sara received a postcard from the FBI asking her to contact them. The FBI agent, after complimenting Sara on her intelligence and capabilities, asked her to identify people by name from the photographs he had; they were of men in their thirties, while Sara was in her mid sixties. All were Communist party members, many of whom had died of illness or old age. "Now listen," she asked him, "you're showing me pictures of handsome young men. Why do you bother?" The agent responded, "Remember what Kennedy said, that I shouldn't ask what the country can do for me, but what I can do for the country."

At that time, Sara was volunteering at an old age home and in the children's ward of St. Luke's Hospital, collecting toys for the children and spending time with those who hadn't any visitors. She was also fighting for the Harlem 6, against the Vietnam War, and for better housing. So she told the FBI agent, "I didn't wait for Kennedy to tell me to do something for my country; I always did. If I would be you, I would be in Mississippi to help the people there register the blacks to vote." Sara never heard from the FBI again.

Sara Plotkin: An Oral History

Editor: Arthur Tobier

Book Design: Miriam Berman

©1980 Community Documentation Workshop

St. Mark's Church-in-the-Bowery

131 East 10th Street

New York, NY 10003