| 20. Bucharest and Aliyah | |||

|

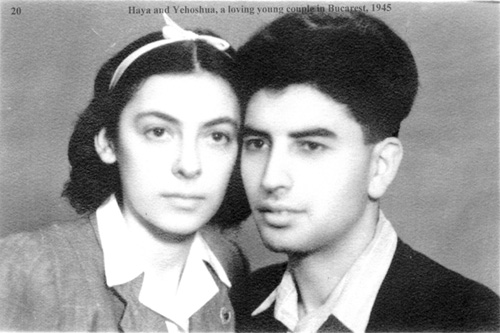

Auntie Roth welcomed me warmly. After we took seats, she cordially asked about my family. I had the feeling that my story had a benevolent listener. Then I told her how much I loved Ilonka and sensed that she was reciprocating my feelings. I asked her consent to our marriage. I will never forget that winking smile in the corner of her eye that accompanied her answer, ”My dear boy, I am advising you to leave my daughter alone. She doesn’t suit you. She is spoilt, so far she has not prepared a single cup of tea by herself. She needs a bank president.” I replied, also smiling, “Dear Auntie Roth, don’t worry, she will learn everything.” At that, she embraced Haya and asked her teasingly, “Do you really want such a boy? Instead of promising to hire proper help for you, he said that you would learn to work!” Then she kissed her with warm, motherly love. We were in mid-May when Pil (Moshe Alpan), the secretary of our movement, visited our Hakhsharah. He brought us the happy news that all the “passengers” of the “Pilot Group”, who had been sent to Eretz Yisrael by the Rescue Committee the previous summer but had been held up in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp by the Germans, had arrived in Switzerland and were awaiting their Aliyah. Since both Haya and I had siblings in that group, we considered ourselves next in line and expected our Aliyah very soon, hoping to meet our surviving relatives in Eretz Yisrael. We were to depart for Bucharest by the end of May where we would join an earlier group of our movement awaiting Aliyah. Haya asked for extra time, because she was unprepared to leave her mother so abruptly, and Pil granted her a short delay, promising me to see to it that she should soon follow me. Haya’s mother wanted us to marry before our departure, but those were days when weddings could not take place according to Jewish tradition. We promised her that we would marry as soon as we settled down in Eretz Yisrael. I departed on May 31, 1945, in the company of two girls and two boys, but without Haya. Our parting was frustrating. From her mother we parted as family members, and she also promised that she would send Haya to join me as soon as possible, and she would also follow us very soon. The train journey from Budapest to the Romania border could in no way be described as a luxury excursion. Russian soldiers jammed the wagons and passengers occupied the steps and the roofs of the cars. From boarding to leaving the train we had to constantly fight our way and guard the girls and our meager belongings. The journey lasted three days. One of our companions intended to get off at Arad in Transylvania (the Western, Hungarian region of Romania). Before he departed, he taught me a few practical sentences in Romanian, so that I would not get lost, e.g., “Where is Vasile Lascar Street, please?” At the border control I could exclaim, “I am a refugee!” Nobody had personal documents, and not one of us knew the language, but I would not exaggerate by estimating that thousands of people were crossing the border this way. We crossed it without any difficulties near Arad; From there to Bucharest we traveled two more days. I do not remember what we ate during those days, because we had no Romanian currency, only a few Hungarian Pengős, which were practically worthless there (as well as in Hungary itself). At the Bucharest railway station we had some difficulties due to our ignorance of the language. When I asked the policeman the question I had learned from our Transylvanian companion, “Unde este Strada Vasile Lascar?”, he started to explain at high speed. Then, seeing my expression of helplessness, he repeated his explanation while gesturing with both hands, pointing to the left, to the right, and straight forward. I tried my French, but he signaled that he did not know this language, then pointed in a certain direction, saying “Français”. Following the indicated direction, we indeed met another policeman who did speak French. Thus we arrived at last at our destination, where our friends welcomed us warmly. There I also met old acquaintances, members of the Movement I had not seen for a long time, such as Yehuda Wertheimer, my buddy from the forced-labor company who had fled with me from that unit, and Meir Lőwinger, a schoolmate of my brother’s from Bratislava in the mid-thirties. About seven years my senior, he was the oldest person in the whole group, a senior member of the Slovak Movement. While we greatly enjoyed our reunion, he introduced me to his group and discussed some pressing issues, asking me to take over his leading position. I refused and suggested that we shoulder the responsibility together from then on. While we were waiting for our Certificates (immigration permits to Eretz Yisrael), the main issue on our agenda was the assignment of priorities for departure. Considering the shortage of legitimate immigration quotas, some members of the group would have to stay behind and wait for the next Aliyah. Our selection criteria were the length of membership and the personal activity of each member in the movement. A few days after my arrival we were discussing this issue at a general assembly of the whole group. It was unanimously agreed that Meir and I would head the list. I demanded that my fiancée Haya be included. There were voices claiming that she had no right to be on the list, since she was not present, and surely not at the top. I argued that she would be arriving very soon. In the midst of our heated argument, Haya entered the room like a Deus ex machina with perfect dramatic timing. Happily I flew into her outstretched arms while her position in the priority list was confirmed unanimously. It is hard to describe our happiness and gratitude that both her mother and Pil had kept their promises of sending her to follow me.

All groups waiting for aliyah in Bucharest enjoyed the financial support of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), a worldwide Jewish charity organization (which headquarters in America), in the form of a monthly per capita allotment. I for one did not want to live on charity and was determined to earn my own living. With Dov Klein, a newcomer to the Movement I started to work in Metaloglobus, a factory of metal products, where our salary exceeded JDC’s allotment. We took no part in the production process, but performed special maintenance tasks. We neither knew nor cared whether they had plans for our “future” in the factory. The management paid little attention to our work, and we had a really good time, joking around and laughing a lot. Dov proved to be an excellent companion, and we developed a warm close friendship. During our work, I also used the opportunity to get acquainted with other workers and thus with their language. My former basic knowledge of Latin and French was of great help in learning Romanian. Since the Communist Party ruled Romania, every worker got a free copy of the Scīnteiă (The Spark), the Party’s official daily. I tried to read it with the help of my new Romanian friends. By asking the meaning of all words I could not understand (I had no dictionary, of course), I made progress until one day I realized that I could grasp the greater part of a shocking news item under the gigantic headline: BOMBA ATOMICĂ and report it to the group. From that day on, I studied the newspaper more seriously and kept reporting about the world politics at least once a week. I also managed to receive the Renaştereă (The Revival) and include the happenings in the Jewish world in my weekly report. I personally profited by acquiring another language, Iwouldn’t say mastering it, but I was able to understand what I read and heard and to make myself understood. I even ventured to write a letter in Romanian to the management of Metaloglobus when the time for parting arrived. While taking walks around Bucharest we were pleasantly surprised by the abundance of vegetables, fruits, pastry and delicatessen available, compared to what we had in Budapest. Our sparse budget left us no allowance for luxuries, but sometimes we ventured into an ice-cream shop to taste the famous îngheţată cu frişcă (ice cream with whipped cream) to remember something of the tastes of Bucureşti (Bucharest). Our aliyah was put off from week to week, due to a disagreement between the Four Big Powers (France, Great Britain, the USA and the USSR) whose representatives had to agree upon foreign policy issues, such as certifying the legitimacy of ships carrying people from Communist Romania to the British Mandate of Palestine. I still have my Certificate (Immigration permit into Palestine) issued by the British Embassy and signed by the three other ambassadors. At last, at the beginning of October 1945 we got the signal to ready ourselves for the journey. Dov and I notified our superiors that we were going to leave. The management tried to persuade us to remain and promised promotion with tempting salaries, but we thanked them for their kind hospitality and generous offers and insisted on our plan to leave for Eretz Yisrael. We prepared for the great adventure of our lives, the Aliyah, with excessive joy and high spirits, although it meant leaving the luxurious villa in the “diplomats’ quarter” we had inhabited. My friend Dov did not join us and I knew I would miss him. In those four months of common work with jokes and laughter, we had formed a close friendship. He returned to Budapest, where he met Anci Cseh, the happiness of his life.

When we boarded the ship, it gleamed sparkling white everywhere, but the number of passengers considerably exceeded the cabin spaces. We, the younger ones, had to find places on the deck; it was not too comfortable, but who cared! The only thing that mattered was that we were on our way to Eretz Yisrael; nothing else. At 4 A.M. the ship raised anchor and started to leave the port. All the passengers assembled on the deck and, on a given signal, started to sing the Hatikva, the anthem of the Zionist Organization, which later became the anthem of the State of Israel. Many people wiped their eyes, and so did I. Enthusiasm and elation shook the whole crowd standing at attention. I have to use superlatives in trying to describe what I felt and the expression on the faces of everybody around me. At the break of dawn we woke in the Bosphorus Strait; the Black Sea was behind us. When we finally left the Dardanelles, we stood at the aft rail, looking back to Europe. As we were drawing away from its last islands, I breathed an oath never to return to that continent where the soil was soaked by so much Jewish blood! Our voyage was slow but smooth, and on the morning of the fifth day we saw “land,” a mild slope on the horizon where a town came into view. I needed no guessing; I recognized Haifa at once, remembering the photos I had seen. I also identified Mount Carmel in the background. I lack the eloquence to describe the outburst of joy and excitement among all the passengers at the sight of the Promised Land turning into reality. As Zionists, we reached the realization of our ideals. For me, this was much more—the pious prayers of my childhood had come true; the visions of our great prophets, who envisioned, thousands of years earlier, that “at the end of the days” we would “return to our ancient homeland,” came unintentionally to life in my excited mind, during those unforgettable moments. On Friday, October 27, 1945 we anchored in Port Haifa. |

|||