|

M O S C O W - M O S K V E |

||

|

|

and Maps Reading from Moscow Research and Links |

The Mechanics of Emigration: One Family's Story

by Carola Murray-Seegert, Ph.D. Like most other refugees leaving Moscow in 1891, the Weinstein family planned to make its way to the German port of Hamburg. They arrived early to buy tickets for the slow, Third Class train that left Smolenski Station at 7 pm and then waited amidst a crowd of anxious passengers. The scene became chaotic when the carriages pulled up to the platform. Moshe, age 12, did his best to help his stepfather Jacob carry the heaviest boxes and bundles to the baggage car. His mother Malke kept a firm grasp on Simon, who was only 5, while Freida, 17, and Dwore, 11, competed with the crowd to save seats for their family on the wooden benches in the nearest carriage. It would be a long, exhausting journey in the summer heat. The train followed a route from Moscow through Minsk, Brest and Warsaw to the border of what was then East Prussia (near today's Polish city of Poznan). Although an express could cover this distance in a bit more than two days, the cheap train took 60 hours, halting at every whistle-stop. Perhaps the Weinsteins broke their journey, if they had family in one of the towns along the way. On the other hand, since the contest for places on the train was so intense (Moshe's family travelled during August, the busiest month of the 1891 mass evictions), staying on the train may have been the more sensible option.

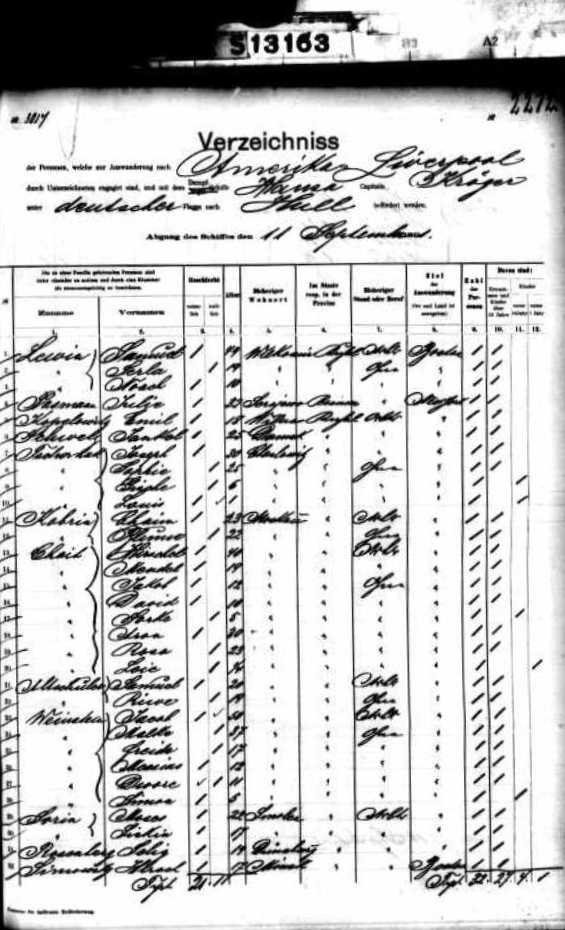

At the Prussian border, Russian police checked every male passenger for an exit permit bearing an expensive set of stamps and an exact description of all members of his party. Once Jacob's permit was approved, Moshe and the other children helped drag the family's bundles and boxes to a new train, hoping to find seats for the journey to Berlin, which took another day and night. Although the refugees were not allowed to enter Berlin itself, their train stopped at a suburban station where the passengers could briefly stretch their legs; there, members of the city's Jewish Relief Committee distributed tea, kosher bread and soup, and provided medical attention to those who needed it. An hour later, the train continued on its way to Hamburg - taking an additional day and night to reach the port Once in Hamburg, the local Jewish Relief Committee again came to the aid of the Moscow refugees, providing meals, simple accommodation, medical care and even steamship tickets. Most families spent about two weeks waiting for their turn to sail. After five to six days confined in a crowded train carriage, everyone needed to visit the public baths, get de-loused and choose new clothing; they also had to stock up on kosher provisions for the upcoming voyage. While it must have been a relief to reach Hamburg, the refugees dreaded the discomforts of the approaching ocean voyage. They worried, as well, about passing the multiple inspections they faced. Each passenger was closely examined at each stop along the way, since shipping agents were required to certify the health and intellectual fitness of all passengers (or pay return passage to Europe for any rejected by the port of destination as 'likely to become a public charge'). Instead of taking the faster, direct route to the U.S., which was expensive, the Weinstein family purchased tickets from the H.J. Perlbach Company for the route via Hull and Liverpool. Their names, ages, and last place of residence were carefully recorded on a shipping manifest.

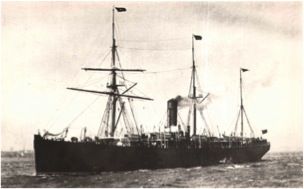

When they arrived in Hull, England a day or two later, they were taken directly from the ship to a waiting room on the docks, where there were bathing facilities. After a brief rest, the travellers boarded a special train for 'transmigrants' that took them straight across England to the busy port of Liverpool, a journey of about 7 hours. In Liverpool, the Weinstein family had to wait several days for their ship. There, they again faced a medical inspection and another bout of de-lousing. Kosher provisions had to be bought, as only bread, water and herring were provided on ship. Morris and his family embarked around 14 September on the S.S. Bothnia, settling into the steerage quarters that they would share with 1,000 fellow-passengers for the next two weeks.

The Bothnia sailed from Liverpool to Queenstown (Cork) Ireland, where the ship picked up additional passengers and then headed across the Atlantic, arriving in New York City on 28 September 1891. At Castle Garden (Ellis Island was not yet functioning), U.S officials carefully checked each immigrant, detaining or even rejecting those who did not pass the examination. We can well imagine the Weinsteins' relief when they could finally start their new life in New York City. Sources and Further Reading BallinStadt Emigration Museum, Hamburg (Website in German and English from the museum that recreates the immigrant experience at the Hamburg port.) Evans, Nicholas (1999) Migration from Northern Europe via the Port of Hull, 1848 - 1914. Norway Heritage. Retrieved 6 March 2012. (A detailed description of the journey from Europe to Hull and onward to Liverpool) Evans, Nicholas (2007 ) Journeys. Moving Here: 200 Years of Migration in England. Retrieved 11 July 2012. (Website with well-researched text and historic images illustrating the Jewish experience in Britain, especially the mechanics of immigration) Frederic, Harold (1892) The New Exodus: A Study of Israel in Russia. Digital version at the Open Library. Retrieved 15 July 2012. (For specific details of the routes taken by refugees, see Ch XV, pp. 269-270 ) Gottlieb, Laura (7 February 2005) Migration from Europe to the US. JewishGen Discussion Group Archives. Retrieved 11 July 2012. (This Discussion Group post includes fascinating specifics about routes, the cost of tickets and marketing tactics in the Pale. One must register at the JewishGen site to retrieve this post.) Map of European Railroad Routes and Stations, with inset showing Moscow-St. Petersburg line, 1892. Courtesy of David Rumsey Historic Map Collection. | |||

Copyright © 2012 Carola Murray-Seegert Ph.D.