Family Roots

I had the wonderful opportunity to travel to Poland and the Ukraine to research my Jewish ancestors with the support of the Friedman Brothers Foundation. The trip was moving for me not only in terms of the genealogical information obtained but for the new appreciation of the history of the area and the emotional ties of Jewish Americans to those places.

There were 20 people on the trip, of varying ages. Most were there to return to a town left during the Holocaust. Some like myself went to research family roots. We flew to Warsaw from New York. We were met in New York by the trip leader, Miriam Weiner, a certified Jewish Genealogist, and an expert on genealogical exploration in the Ukraine and Poland. We also met Sy Rotter, a filmmaker who created a documentary film from the trip ( watch A Time to Gather Stones - Part I | Part II). The trip was designed to gain access to various archives, visit cemeteries, visit holocaust memorials and provided for each of us to visit the town or towns where he or she had ancestors. I was to visit the towns of Kopaigorod and Bar where the Friedman family originated. A driver (Yuri) and a translator (Igor) were provided for me.

I brought back a number of documents and birth certificates of members of the extended Friedman family. These were obtained from a rabbi’s book which recorded births in Kopaigorod in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

I would like to share with you a diary of the day I spent in the towns of Kopaigorod and Bar.

~ July 14, 1992 Stopping for a Meal ~

I am writing from a hotel in Bar (the birthplace of Ephraim Friedman, my great-great grandfather). Yuri and Igor (driver and translator) are sleeping in another room. I have a “suite”. There are four Ukrainian women in the other part of the suite watching a soap opera on TV. They were so disappointed that they couldn’t watch their favorite program, so I invited them in, as this seems to be the only TV around. The bathroom is bad, but otherwise the room is fine, pretty fabrics on beds, bright rug on painted wood floor, no ornaments on walls, few light bulbs. I like it better than the Intourist Hotel in Kiev. Furniture is varnished wood and plain. The whole room plus another room for Yuri and Igor cost a total of 140 rubles which is less than one dollar. Dinner (at noon in a restaurant), was cucumber salad with scallions, bottled water, borscht, bread, black rice with meat and wonderful hot tea. The price for 3 people with a tip was 100 rubles. Amazing. I bought a box of tea. Igor told me how to prepare it.

Use a warm and dry porcelain tea pot. Put in 2-3 teaspoons full of loose tea, teaspoon of sugar, fill teapot one third full of boiling water. Wrap pot in towel and let steep for 2-3 minutes then fill teapot two-thirds full of boiling water and steep a few more minutes.

Igor thinks adding more sugar ruins the flavor of the tea. He also said that there are many different grades of tea and the worse grade goes into the tea bags we get at home.

The drive from Kiev to Vinnitsa took from 5:00am to 9:30am and from Vinnitsa to Bar was an additional 90 minutes. We traveled in an old Soviet car, but there were no car problems in over 14 hours of driving.

I met the mayor of Bar who was friendly and very willing to talk to me (through a translator). He gave me a handprinted book about the ancient history of the town of Bar and a telephone book from 1988. He said there are currently 22,000 people in the town of Bar, including 432 Jews. There are local archives in the town from 1948 to the present. All other archival material is in Vinnitsa.

~ Searching for Family ~

There are three Jewish cemeteries. One is modern and two are mass graves in the ravine outside of town, for people murdered during World War II. I visited the modern cemetery and one of the mass graves. The mass grave was located about a mile down a dirt path from the modern Jewish cemetery. The ravine was sunny, with birds, cows, goats, potato fields and rolling hills. The grave, in an oasis of trees, was hidden from the road. To get there, after walking about one half mile from town, you need to cross over a mud lake on logs then a moat with a cement bridge. The entrance was locked with a padlock, but inside you could see that there was a stone monument in a small walled garden and a painted wooden bench. The writing on the monument did not mention Jews. It just said that many “prisoners” were killed, but undoubtedly the majority of those killed were Jewish. I did not see the other mass grave.

The mayor of Bar said that during the war his grandmother hid three Jewish families. His father spoke fluent Yiddish. The mayor, whose name is Vladimir, said he has a Jewish nickname. He remembered that there had been large families with the names Friedman and Spector, but he said that none were left. He said that the most beautiful house in Bar used to belong to someone named Friedman.

The mayor had three telephones (red, green and yellow), in his office. A large world map was on the wall facing his desk. There was a large old fashioned safe in the room. He had a secretary outside his office. She worked on an old typewriter. There were no xerox machines, fax, paper clips, memo pads or marker pens.

There is an old synagogue in Bar (where Ephraim Friedman probably worshiped), an adobe-like building, falling down, with broken windows. It was built in 1807. It was a synagogue before 1917. At some point it was also a religious school. A famous Ukrainian writer, Mikhail Kotzubiuski, of the second half of the 19th century, used to study at the Bar Synagogue school because he heard that the Jewish school was the best. At some point, a dome was added to the building. Now the building is boarded up. After showing and speaking about the synagogue, the Mayor said, “Neither you or I are guilty for what happened at that time”. He seemed ashamed of the condition of the building.

~ Kopaigorod ~

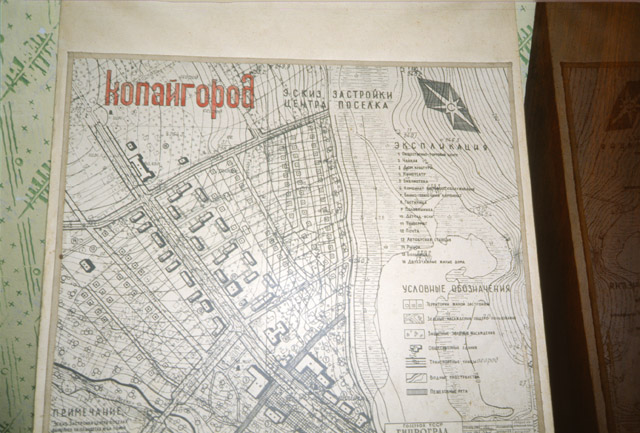

After the mayor showed us the synagogue and we had dinner (as described above) we drove to Kopaigorod. The barely paved road to Kopaigorod goes through rolling green hills and fields. We saw many cows, goats and chickens on the way as well as storks. As you enter the town, there is a large hospital on the left with a blue design painted on the windows. Working in the hospital, I later learned, are 15 doctors, 2 dentists, 3 surgeons, 1 gynecologist, 2 pediatricians and 1 X-ray technician. There was a also a store and other buildings. The mayor’s office had very tall doors which were covered with leather. The hall was very dark with tile floors. In the mayor’s office was a large abacus and an old plan of the town of Kopaigorod.

The mayor called in one of the Jewish people of the town. Samuel Lazarovich Fishilevich came with his two granddaughters. He was so eager to find out the names of people I was looking for that he tore the paper out of my hands. He had silver caps on all of his teeth. He had heard of a large family of Friedmans that had all left in the 1920’s. He had also heard of the name Spector.

I gave the mayor a map of Madison, Wisconsin (my hometown), a letter of introduction from my mayor in Madison (in Russian) and some postcards of Madison. Igor took a picture of the mayor, Mr. Fishilevich, and me.

We next went to the Jewish cemetery (after Mr. Fishilevich went home to get a coat, covered with war medals, to cover his shoulders). The cemetery dates from the 1920’s. There was an older one, but it was destroyed during World War II. The cemetery consists of 200-300 stones, many almost buried in grass and thorny weeds. Some tombstones had photos attached to the stone. Mr. Fishilevich said there were no Friedmans in the cemetery but two Spectors. He finally found the two Spector stones. I took about sixty photos of gravestones. I gave the granddaughter some gum and crayons and pens. I took a picture of Mr. Fishilevich by the grave of his son-in-law which he wants to send to Israel to his grandson (I mailed him the photos).

~ Vinnitsa ~

I could have spent many more hours exploring the town, but we were obligated to return to Bar, where we stayed overnight. We ate food we brought with us; no meals were available at the hotel. The following day we drove to Vinnitsa, where I obtained the birth certificate of my grandfather, Solman Friedman, and about 10 other birth certificates. I took photos of the rabbi’s book. I was charged 10 US dollars per document plus an additional two dollars for each photo, and a dollar for each year I searched in the book.

The entire trip was very exciting and meaningful for me. I will never forget it.

More Information

» Ukrainian shtetls

If you are using the Chrome browser, you may switch the translation to English.