|

District Krasnystaw, Province of Lublin |

![]()

Żółkiewka Memories and Stories

Walking Forward to

the Past

Jim Haberman

During the 1980's my

job required occasional visits to my then employer's Warsaw office. During one

of these visits, I was fortunate enough to be able to explore my paternal

genealogical roots.

Like most Americans,

I had failed to take advantage of the living databanks that were my

grandparents, and to obtain from them the valuable details of their and their

ancestors' origins. My father, the only son of an only son, experienced the

death of his biological father, Abram Haberman, as a young child. While my

father's mother, Rebecca LAFER HABERMAN GOLDBERG, lived to a ripe, old age

(though exactly how old we did not know - more on this later), leaving us in

1973, the only useful information regarding her origins that we recalled were

the name of the Polish village from which she came (which she pronounced ZHOW-kehv-kih) and the fact that the

village was a half-day horse cart ride from the city of Lublin, in present day

southeast Poland.

My Bubbee was the archetypical matriarch and the grande dame of my father's side of the family. She was the

center of the family's universe, around whom all members rotated and to whom all were drawn. She represented the very best that

America offers to those immigrating to its shores, rising, through her own hard

work and initiative, from abject poverty to successful Detroit restaurateur.

During the course of

a telephone conversation with one of my Warsaw-based counterparts a few weeks

prior to a planned February 1987 business trip to Europe, which was to include

a visit to Poland, I had casually mentioned my grandmother's origins, including

the sparse (to say the least) details that I possessed. Upon my arrival at

Warsaw my colleagues had a wonderful surprise for me. They had located what

they felt fairly certain was my grandmother's village

- Żółkiewka (pronounced ZHOH-kehv-keh). Furthermore, they had arranged for a car and an

English-speaking driver to bring me there.

It should be noted that

1987 was near to, or perhaps just after, the low point in U.S.-Polish

relations. The U.S. had recalled its ambassador to Poland following the

heavy-handed Polish/Soviet reaction to the Solidarity movement's efforts to

reform the Polish Communist state. The iron curtain would suffer its very first

cracks as a result of this period in Polish history, which a few short years

later would result in its complete collapse.

We left Warsaw late

the following afternoon in my guide's worse-for-wear Maluch

(the ubiquitous tiny Polish-made Fiat automobile) taking, as I recall, 2 to 2½

hours to reach Lublin (some 30 miles from Żółkiewka), where we

spent the night. The following morning, I asked my guide to speak to the hotel

staff and attempt to learn whether there was a Jewish presence in Lublin - a

synagogue, a Jewish community center, etc. I thought that speaking with local

Jews might yield information that would be useful during our visit to

Żółkiewka. Based on my knowledge of the Holocaust, I was not

optimistic. The staff directed us to a local social service office. We phoned

them, but the best they were able to offer was the name of an elderly Jewish

man living not far from our hotel. The guide phoned the man and he immediately

invited us to visit him. He enthusiastically welcomed us to his tiny apartment,

where we talked for a short while. He told us that prior to the Second World

War Lublin had a Jewish community numbering around 40,000, and that he was one

of around 40 remaining. He had escaped the holocaust by fleeing to the Russian

border, and returned to Lublin after the war. Afterwards he accompanied us to a

small holocaust memorial in the center of town. After visiting the memorial, we

returned him to his apartment, where he provided directions to a large, old

cemetery with a Jewish section on the way out of Lublin. There, I was surprised

to find the Jewish graves to be in remarkably good condition. The grave markers

appeared authentic, and I am uncertain as to how they had escaped destruction

by the Germans.

As we departed the

cemetery en-route to Żółkiewka, we passed, on the outskirts of

Lublin, Majdanek, the concentration camp constructed

specifically for Lublin and the surrounding area. My driver asked if I wished

to stop and see it. I replied that I did not feel emotionally prepared for such

an experience at that time.

It was a typical,

gray European winter day as we made our way down the two-lane asphalt roadway,

past the small, thatched-roof homes that dotted the snow covered farm fields.

Horse drawn carts riding on truck tires were by far the dominant mode of

transport on the road. The sights evoked for me what I imagined nineteenth

century rural Poland to have been, until there at the side of the road - a

typical black-on-white government-installed road sign announcing our arrival at

Żółkiewka.

Our first stop was

the village church (Poland is more than 90% Catholic). We explained to the

priest our mission, and asked whether he could offer any assistance or advice

in researching my grandmother's early life. He curtly replied that he could

not, and we made our way back to the near-deserted sidewalks.

We walked a short

distance until we happened across a small community center in which were seated

four or five aged locals sipping coffee. We entered and engaged them in

conversation. I sensed that I may have been the first American they had ever

encountered. They offered us coffee and were very forthcoming in sharing their

remembrances and in recalling the fate of Żółkiewka's Shtetl.

Not surprisingly, it had suffered the same destiny as countless others not long

after Germany's 1939 occupation of Poland. I asked whether any Jews remained in

the area, and they informed me that none did. One of our interlocutors was a

local functionary, and he offered to take us to the town office to determine

what could be gleaned from the municipal records. Until that moment I would not

have ever guessed that this small town had an office, let alone historical

records. As municipal records are often destroyed by conquering forces, and as

this region had been conquered so many times over the years, I was amazed to

hear that any had survived.

As we walked to the

office, the functionary pointed out the location of the town's former Jewish

cemetery. It now looked like any other wooded plot of ground, with no

indication whatsoever of its previous use, or of the many graves that no doubt

still remained. A small portion of the ground was being utilized as a storage

area by a small local construction company. The official told us that the

Germans had ordered the tombstones removed and had them used as fill for road

repair work.

Our host led us to

the austere, unoccupied town office and, pulling a set of keys from his pocket,

unlocked the door, flipped the light switch and led us in. There, on a small

wall shelf, was an amazingly well organized set of small books, each perhaps 10

inches tall by 6 inches wide by ¾ inch thick, three for each year (one each for

births, marriages and deaths).

The town official

respectfully informed us that he would not be able to spend much time with us

and that regulations forbad our photographing or even touching the books.

Whether this no-photograph policy was due to overreaching by the Communist

autocrats or in deference to legitimate privacy concerns, I do not know.

Stanley Diamond, the guiding force behind Jewish Records Indexing - Poland (and

the 'superb JRI-Poland web site), was surprised that I had even been allowed to

view the books, and leans towards the latter explanation.

As was not uncommon among

her contemporaries, my grandmother not only never knew

her birthday, she never knew the year of her birth. As was also not uncommon

among immigrants of her generation, my grandmother never observed an annual

celebration of her birthday. Whether this resulted from the general failure of

many rural immigrants to reconcile the Jewish calendar with the western

calendar following immigration to the west, the higher degree of attention to

basic survival that Shtetl life required, or some combination of these or other

factors is unclear. What is clear is that my father's Ohio birth certificate

indicates that his mother was 26 years old at the time of his birth in 1917

(presumably establishing her year of birth as 1890 or 1891), however Dad always

suspected that her declaration of age at the time of his birth was, at best, a good guess.

After I conveyed my

estimate of my grandmother's birth year to the town functionary, he pulled the

1891 birth book from the shelf The book's lined pages were hand-written in Russian,

as that part of Poland was then under Russian control. He carefully perused the

volume's text but, alas, no luck. Then, the 1890 book.

Again, nothing. As a last ditch effort, he agreed to

check one more year - 1889. Voila! There it was - my grandmother's birth

record. Date of birth: 13 September 1889. Father: Keilman

LAFER. Mother: Sura LAFER. As our host was in a hurry

to conclude our visit, I left the office feeling a combination of great elation

at having located the birth information, and disappointment at having missed an

opportunity to delve further into the records.

I later requested and received a modern version of my grandmother's

birth certificate, on which was typed in Polish the information from the

original book. Interestingly, it translated the Russian Cyrillic representation

of the family name as "LAUFER", not LAFER, as it had earlier been

Americanized. In the last few months, thanks to JRI-Poland and it's highly

skilled and dedicated group of volunteers, I have located basic information

regarding my grandmother's parents and grandparents (my great-great

grandparents), whose identities were heretofore unknown to me and my parents.

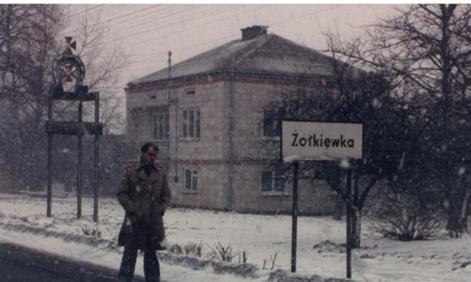

As I left my grandmother's birthplace to begin the long drive back

to Warsaw that late afternoon in 1987, the temperature had dropped

precipitously and heavy blasts of wind driven snow had begun falling in

earnest. Although the day was slipping away, a blizzard seemed in the offing

and a long drive back to Warsaw lay ahead of us, I had my guide stop the car at

the edge of town so that he could snap a photo of me standing next to the

Żółkiewka road sign. Hopefully, one day I'll return there, as

one more step in the research that I'm certain I have only just begun. Stay

tuned.

[Top]

![]()

Back to the Żółkiewka home page

JewishGen Home Page | KehilaLinks Directory

![]()

Compiled by Tamar Amit

Updated 05 March 2024

Copyright © 2011-2024 Tamar Amit

[Background based on image by The Inspiration Gallery]