Journey of Sharon Weinstein to Ostropol

January 30, 2001

Zhitomir

Tolik talked about his life in Lviv. He said that he had been a national swimming champion . His instructor in Lviv was Gregori Mikhael Weinstein, who at age 55, left for Haifa. His other instructor, Vira Lipman, now resides in Tel Aviv. The city of Lviv (in Ukrainian) or Lvov (Russian) in southeastern Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939, under the terms of the German-Soviet Pact. Lviv was subsequently occupied by Germany after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. In November 1941, the Germans established a ghetto in the northern sector of the city. Thousands of Jews were killed in the ghetto and in the Belzec killing center.

As we traveled, we passed a magnificent birch forest. Nazis had occupied the area during the war. During Soviet times, if you had a fruit and produce garden, you paid taxes on the quantity of fruit your garden produced.

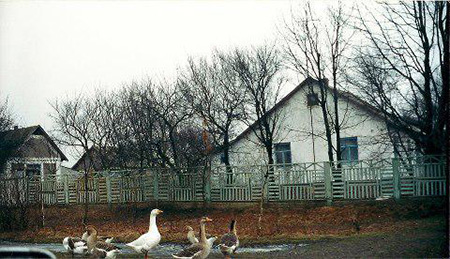

We drove through Chedani; the name of the town means 'miracle' city. We shared the highway with horse-drawn wagons and carriages, and saw very few cars. Tolik offered some geographic boundaries. Ostropol was 50 km to the Austria-Hungarian territory during the time that our ancestors lived there; it is now 1400 km to the town of Brody, where many egg exchanges occurred. Tolik suggested that egg exchanges might have been in violation of local law. The town of Luba was our next stop; Luba is the home of the Roman Catholic Church and the Caritas Center. Residents have received substantial aid from the US and Canadian governments. We approached a stop sign that was in English, rather than Russian. It marked a traffic circle and a main intersection. Chickens, roosters, and geese crossed the intersection quite slowly. Tolik pointed out a flourmill that is still in use; it was as if time had stood still in Luba. He also showed me the Transfiguration Church.

Traveling throughout the region, we searched for Kalinin Street in Staryostropol. We passed the main administrative building, a school (where Dean had visited), and the central bus stop. Stopping to ask several people along the route, we were directed to a fork in the road. Just west of Slobodah village and Adampil (town of Adam), we found a music school and a post office. Tolik entered the post office and asked a customer for directions. He returned to the car accompanied by Victor Sergeivitch Gorbachuk, who led the way to our destination. Victor Sergeivitch told us that mail is delivered on Wednesdays and Saturdays. It costs 4 hgryna to send a letter to the U.S., and the monthly pension is only 45 hgryna, from which utilities must be paid and groceries must be purchased. He also said that in 1959, there were 10,000 people in the district; the current population is less than 2000. He pointed out a small hospital, 4 stores high and Stalinesk in style. Apparently, there are 2 physicians in the era. Originally opened as a 100-bed hospital, there are now 20 staffed beds.

Turning onto a cobblestone road, we saw the mud-covered Kalinin Street sign and we approached the home of Anatoly Polansky and his wife, Katerina (Katya).

Anatoly said that he had been eagerly waiting for us. He greeted us warmly, and led us through the outer yard to a pile of shavings, currently used as a doormat. After scraping the mud from our boots, Tolik and I entered the vestibule of the modest home. The cold, dampness, and lack of light did not matter because the light shining from Anatoly’s eyes was enough to warm the entire room. Anatoly is 69, and his wife is 60. They have been married for nearly 20 years. His first wife was Jewish; Katya is Orthodox Ukrainian.

He led us to his desk, and immediately spoke lovingly of his visit with Dean five years ago. He had written a letter to me, in which he described his current situation. Tolik translated it onsite.

"My name is Anatoly Ostropovich Polansky. I ask to describe my situation in which I permanently care for the Jewish cemetery and guard it from vandals. I took this responsibility on my own. I am the only Jew in Ostropol. Soldiers killed as many Jews as they could locate in 1942. All of remaining Jews moved after that time. The local authorities take care of only orthodox cemeteries (Greek and Roman Catholic). No one takes care of Jewish cemeteries except me. In 1997, Dean Echenberg came and promised to support me financially for my activities. He was contacting with the Peace Corps where he registered the necessary documents. The documents said that Polansky would be receiving $15.00 per month and a one-time payment of $100.00 for his (my) work. The manager of the office, Bob (Robert) called me and invited me to his office where I met with him. Thanks to an interpreter, I understood him and he gave me all necessary documents to sign. Those documents were about money and wages. He did not give me a copy of the documents. I read them and signed them over 5 years ago. Russian people say, "if there would be some honoraria for his work, it would be appreciated and would support my poor status." In spite of all this, I am still believe that Jewish people lived properly, and will be cared for properly when they die. I am working for the principle and means without bread. These people, in spite of their death, deserve my care. Now, I need an operation. I have adenoma. I did not have the surgery yet because I have not enough money, and for other reasons I can tell about. One year ago, when I was ready to go to the hospital, my son, Ihor, died in the Russian war, and I had to use the money to go to Moscow to return his body to this region."</p>

Anatoly and I discussed his need for surgery, and whether or not the local hospital could provide it. He told me that the main hospital in Stantinokov would do it for 700 hgyrna or $140.00 (including the doctor bill and all medicines). He said that he has several bottles of heart medicine, including cardiodine, validol, and others. He takes what sounds like nitroglycerin as needed. ... He turned his head and you could see that he was shielding his tears from my sight. He and Katya embraced me and held me tightly.

The Polanskys survive on a $25.00 monthly pension and food parcels that he travels to Kmelnitski City to obtain from Chessed Beth. They grow potatoes, fruit and some other vegetables in their yard. Polansky then led Tolik and me to the cemetery sites while Katya prepared tea. Polansky has served as cemetery caretaker since the engravings on the stones, many of which had eroded with age. He lived on the grounds of old (starry) cemetery; the Nazis took his house and he was killed at gunpoint in 1942. Polansky erected a brick fence around the old cemetery. Neighbors took the bricks, and parts of the remaining headstones to construct their own homes. He has asked neighbors not to let their animals roam throughout the cemetery, and according to him, "no one listens and no one has respect for the dead."

We walked from one end to the other; he pointed out where people, including our ancestors, who died prior to 1909, would have been buried. He estimated that 10,000 bodies were buried in the area. He also showed us the burial ground of his grandparents, and the rabbi of the community.

We then crossed the road to the new (novy) cemetery, adjacent to the Polansky home. He had erected a fence to surround and protect the property. Although it was a cold winter day, you could see that plantings and trees added beauty to the site. He recently expanded the burial area; there are 400 bodies at present, including those of his parents. He has a small dacha-like building where he keeps his supplies. He also has a plank of wood laid across two large rocks on which he sits to reflect on his work during the warm weather. It is a source of peace for him because when he is there, no one can see him or hear him or his thoughts.

We returned to the home that he had built with his bare hands. Trained as a carpenter, he was employed as a driver for the Germans during the war. As a Jew, he was given the oldest, most unreliable car to drive. We washed our hands and sat down for tea. Katya had prepared plates of her own pickles, perogi, walnuts, and tea. We enjoyed homemade wine and home-distilled vodka, and we shared stores about our families. Polansky told me that there were two "Weinstein" families in the Ostropol region. They left prior to the Nazi invasion. Their relatives were buried in the old cemetery. He asked if I might be related to them, and of course, I did not know. He wrote a letter to Dean, with whom he was very impressed. I plan to send the translated version to him next week.

We remained with the Polanskys for photos, more stories, and camaraderie for several more hours. We agreed to take a 50 pound bag of potatoes, carrots and apples from their garden to Anatoly’s sister in Lviv. She has breast cancer, and she recently lost her daughter and son-in-law. She is caring for a one-year old grandchild alone. Polansky hoped that we might locate some used clothing for the child. I promised nothing, but I planned to pursue the purchase of clothing when I arrived in Lviv on the 21st. We hugged and kissed like old friends who had recently been reunited after many years' absence. I felt as if I was truly 'with family.' Polansky asked me if all of the Echenbergs were 'so warm and wonderful.' I replied that not only were the original Echenbergs wonderful, but so too were those who joined the family through marriage.

Tolik and I re-arranged the car to make room for the potatoes and fruit. Anatoly and Katya accompanied us to the car and gave us a bag of walnuts for our journey. It has started to snow lightly, and the white flakes on Anatoly’s red face created a wonderful sight. We then departed for Ternipol and the Caritas guesthouse, our overnight accommodation.

We encountered a severe snowstorm along the way, making the road slippery and travel difficult. Snow is not removed form the roads; there is no budget for snow removal and no equipment. The local officials believe that after several cars pass, the road will clear somewhat.

Ternipol

Because of the storm, we arrived in Ternipol two hours later than expected. The guesthouse, home to an orphanage and other Caritas programs, had 5 guestrooms, no heat, and no hot water. We lit a fire in the main living room, and sat there with pots of tea to remove the chill from our wet, cold bodies. I planned to gather as many blankets as possible for what promised to be a very cold night.

Despite the cold, I felt warm within. The day had been long, but wonderful. My visit to Ostropol was a moving experience, and one that I shall not soon forget. In my work in the former Soviet Union over the past 9 years, I have been a part of many life experiences. I have witnessed birth, death, surgery, and illness. I have met and known some very wonderful human beings, and the Polanskys clearly earned a place among the very best. We are fortunate to have them caring for the cemetery and home of our ancestors in the former Ostropol region. They now have money to last for awhile. Some of it, I'm certain, will be used to visit his sister in Lviv and to make plans for the care of her grandchild when she is gone.

I plan to communicate with Anatoly in Russian by email to Caritas Ukraine. They have promised to download the letter, and mail it from Lviv to Staryostropol. I want to follow up with Anatoly about his surgery and his plans for a physician visit. I want them to know that the Echenbergs are their friends and that we value what they have done and will continue to do in the homeland of our forefathers.

City Location Oblast Pre-Holocaust Jewish Population1

Kyiv 544 km E of Lviv Kyiv (Kiev) 175,000 (20% of general population in 1939)

Ternipol 127 km ESE of Lviv Ternipol 14,000 (39.3% of general population in 1931)

Zhitomir 140 km W of Kyiv Zhitomir 30,000 (31.6% of general population in 1939)

Khmelnitskiy 348 km SW of Kyiv Khmelnitskiy 13,408 (42% of general population in 1926)

Starokonstantinov 49 km N of Khmelnitskiy Khmelnitskiy 4,837 (33% of general population in 1931)

Lviv 544 km W of Kyiv Lvov (Lviv) 109.500 (33% of general population in 1939