Testimony - 1905 Pogrom Narrative

We are very grateful to JEAN-GERARD SENDER, our dedicated volunteer translator for his thorough work in translating this document. Please note, he first translated it into French and then into English. Please contact the town leader at ukrainesig.phyllis@gmail.com if you would like the French version.

1905 Pogrom Narrative

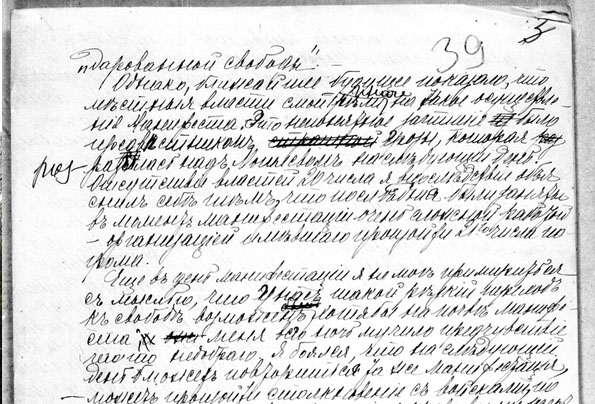

View the original 2 page testimony

Each witness is named and numbered above their individual testimony.

1

NB This first text in the archive was written by the author of the testimony himself, but a second person, certainly one of the inquirers who collected the testimonies, has judged necessary to correct some elements, mainly at the end of the text. I have translated those external corrections – generally written very carelessly - in addition to the text of the original testimony, but with a different colour (green).

Outline of the October events in the town of Mogilev-Podolski

All the events, all the phenomena of social life penetrate our provincial obscure neighbourhood with some delay. This general law applied to the Manifesto of October 17th and to the concomitant anti-semitic pogrom.

The manifesto “on Constitution” came to be known by the mass of the local population only on October 20th, and they really became conscious of its content through the meeting organised on the same day by the local representatives or the Social-Democratic Party.

On October 20th, news ran through the city, telling that people were gathering on Cathedral Square. I had no idea of the character of that meeting, but I was very curious of such an unprecedented – in Mogilev – manifestation of social life, so I went to that square. There I found a crowd of some 2 000 people, hypnotized by the speech of an orator standing on a platform, a certain Tchernyavskiy, student at Kiev’s Technological Institute. He was speaking with so much enthusiasm, and even inspiration, that all were irresistibly captivated by his speech. The two-thousand-people crowd was listening to him with deep attention. His speech was of a revolutionary character. It called the people to further struggle against the bureaucratic government, further struggle for freedom; it called him to boycott the conceded constitution, and to demand the convocation of a popular Constituent Assembly.

After Tchernyavskiy, in the same spirit, but still with great enthusiasm, came another orator, who spoke mainly in jewish language, though some parts of his speech were in russian. This orator underlined, with brilliant colours, the heavy, desperate situation of the working class in Russia, compared to the dominating situation of the privileged social categories; the disastrous consequences, for the working class, of the war against Japan. A last orator undertook to explain the unfoundedness, from the point of view of justice and equity, of the Manifesto of October 17th.

After that last speech, the meeting was declared closed by the same Tchernyavskiy, who addressed the crowd and asked that the demonstration, which was due to end with a march in the town with red flags and the Marseillaise, would not be troubled by any act of violence; he even asked that the Marseillaise would not be sung by the whole crowd, since the Party had at its disposal its own choir (which, incidentally, proved to be awfully bad). And, in fact, the crowd moved on in an exemplary order along Vladimirskaya and Kievskaya streets. Here I think necessary to tell that the police on that day was absent. The main contingent of the mass of the demonstrators was constituted by Jews, mainly young men (and even children), in consequence of which, though in the speeches of the orators the questions of nationalities had not at all been raised, from an external point of view, the demonstration had a “jewish character”.

Red flags, bearing inscriptions with a revolutionary content, had been unfurled. The general quiet character of the demonstration was troubled only by one incident, of which I have not been myself an eyewitness. On Kievskaya Street the crowd met a soldier, armed with his sabre, and insisted that he should take his shapka1 off. To salute the crowd, the soldier draw his sabre, but that gesture was not interpreted by the demonstrators as it should have been, since again were heard shouts : “Take off your shapka!”. The soldier showed his intention to make his way through the crowd, but the crowd took his sabre from him. Following that, I saw some kid marching and strutting before the red flags, wearing the sabre at his shoulder.

About 3 p.m., the crowd dispersed. The complete absence on that day of the police from the streets, in connection with the contents of the recent Manifesto, had lead me to the conclusion that the local authorities judged that demonstration fully legal, and for that one and only reason had not put any obstacles to the manifestation of “granted freedom”.

However, the immediate future showed that the local authorities had a different look on such an implementation of the Manifesto. That inexplicable lull was but a warning for the storm, which burst out on Mogilev on the following day. Regarding the absence of the authorities on the 20th, I later on found out how to explain it: they were busy, at the time of the demonstration, with a quite complex task, organising the pogrom that was due to take place on the 21th

On the day of the manifestation, already, I could not come to terms with the idea that such an abrupt transition to liberty could be possible in our country, even on the basis of the Manifesto. During all night, I was tormented by the premonition of some grievous event. I feared that on the following day would be repeated the same demonstration, that could happen clashes with the troops, producing as usual bloodshed and victims; especially as rumours had begun to go around in the town, according to which a sotnya2 of Cossacks had arrived in Mogilev.

Footnotes:

1 it seems to me preferable to keep the original russian term shapka (which we use in French) rather than the translation cap given by the dictionaries

2 sotnya specific term for a squadron in the Cossack regiments, constituted of about 100 – 120 Cossacks

On the morning of the 21th, at ten, I saw, through my window, a party of six or seven hooligans, armed with iron bars: my premonition was taking a more concrete form. I decided to meet the head of the Town Council, Khlopov, and to warn him of the impending danger. I did not find Khlopov in the Town Council’s office, so I went to the Cathedral, where he attended the red-letter day parade given to commemorate the Czar’s accession to the throne. On Cathedral Square were already gathered the troops, in full dress, and a reinforced police detachment; in the Cathedral was present all the local aristocracy. Khlopov considered that my apprehension was unfounded, and that a pogrom in Mogilev was impossible, since, in his opinion, there were more than enough troops and police in Mogilev to prevent any troubles.

At three p.m. I was struck by some strange rumbling, which soon became stronger and closer. The sound of thousands of voices was melting with the crackle of broken glass. In one disorderly mass had mixed people representative of all strata of the local society. Side by side did walk typical hooligans, and tramps, armed with clubs and iron bars, wearing bucket bags on their left side, as well as representatives of the local intelligentsia: men and elegantly dressed women, members of the police force, military men and civil servants. Dozens of hands held pictures of the Czar, hundreds of voices shouted “hurrah!” and sang the national hymn. All around you could see national flags. While marching, the crowd broke windowpanes.

To understand the character of the pogrom and the crowd’s attitude, it is necessary to take into account the following facts, which inevitably lead to the conclusion that the pogrom was organised by the police and by the henchmen of the bureaucratic regime. As I wanted to prevent damages to the windows of my apartment, I went out, stayed in the street, and when the crowd began to draw level with my home, I managed by myself to contain for a moment its destructive march; not a few hooligans approached me, and each of them asked me the same question: “Aren’t we allowed to break windows?” At that moment came to me a police superintendent (of the district) who was walking ahead of the crowd, and he asked me what the matter was. I reproached him for letting people break windows and ruin the property of peaceful citizens, and I drew his attention to the fact that the windows had been fully broken in the house of my neighbour (not a Jew3); this superintendent, in a very polite form, answered me that he was new in the town, and that he did not know that in this vicinity lived “Christians”. That administrative agent, by all appearances, was convinced that I was indignant only with the troubles to the tranquillity of my neighbour (not a Jew) but that I approved the pogrom against Jews. However, our conversation was interrupted by a new massive flow of the crowd, which carried both of us – my interlocutor and me – away.

The pogrom then began in an explicit way. Looters, armed with clubs, rushed on the shops, broke open the doors and the windows, sacked the shops, and grabbed merchandise, throwing a part of it in the street. All those actions were taking place right in front of the police and of the troops, who did not even try to take the least part in stopping that wild violence. At the corner of Kievskaya and Armyanskaya streets stood a group of officers, with their wives, who were quietly observing the course of events. I approached one of them and asked why the troops stayed inactive; the officer’s face twisted into an ironical smile, and he answered me “Well, the people has been granted freedom!” I asked the same question to a Police Inspector of the first urban district , but that “limb of the law”, probably feeling that he had on his side strength and victory, answered me, approximately, with these words: “You, mister , yesterday, you made speeches on the Square! Well, just wait, wait, soon your turn will come!” I judged necessary to interrupt that conversation, and I went back home, in very low spirits.

There I could observe how groups of hooligans and of soldiers were walking in the streets, bearing stolen goods. From town came the same rumble, and could be heard gunshots. I remember two salvoes; from the second one, according to what was reported to me, were killed two Jews and injured one [was killed one Jew and were heavily injured some others 6]. I happened to be eyewitness of a savage act of violence committed by the enraged mob against that man [against one of the injured men]. People undertook to take him [When people were taking him] to the hospital in a cab, but on his way there [halfway in Kievskaya street], a party of hooligans caught up with him, dragged him out of the cab, tore up the clothes he was wearing. Unmercifully beaten, suffering from multiple wounds, he passed away in the hospital on the following day.

F. D...evits 7

Footnotes:

3 an addition between the lines, from the hand of the external writer (who probably did not understand the intention of the witness; the police officer cannot imagine that the witness, a “respectable looking” man, could protest against the destruction of property belonging to a Jew)

4 it seems that at that time Mogilev, as regards police organisation, and town administration, was divided into two urban districts (in Russian часть [chast’], i.e. “part”) ; when the word “district” was used before (about the “polite” police superintendent), it referred to the Russian term уезд [uyezd], an administrative territorial division including Mogilev and a part of the surrounding territory.

5 there’s no such word as “mister” in the original, but that policeman , instead as addressing the witness with the deferential pronoun вы [vy] addresses him with the familiar pronoun ты [ty] (cf. French vous vs tu, for instance)

6 « external » correction

NB The following texts were not written by the witnesses themselves, but by one or another of the inquirers in charge of collecting the testimonies. Each witness, after his oral declaration, was invited to undersign, if he could write his name (which was the case for all the witnesses except three of them).

2

Duvid Moyshe Bogatin, living in the 1st urban district of Mogilev

On the evening of October 21st, around 6 p.m., I was on Stavisskaya Street, where I had come to meet my friend Yevreyski, and to help him to carry personal belongings from his apartment, which he thought could be plundered by looters. However, when I came to Stavisskaya Street I did not find him there anymore. I stayed there to talk with some friends of mine. We were standing thirty paces away from soldiers who were on patrol on Kievskaya Street, on my left side. Suddenly were fired three salvoes. From the first one a young boy was mortally wounded. Straight away after that first salvo was heard the command: ”again! fire!” or just “once more!”. Then I felt a terrible pain in my chest. After that, as I remember, there was still another salvo fired. A bullet reached me in the chest and went out through my arm. I have been lying here, in the (jewish) hospital, since October 21st. The soldiers fired without any previous warning, and without any occasion given from our part. No shots were fired from our side. On that spot, we were five or six Jews, and near us were not any looters. I do not think necessary, for the time being, to raise a criminal prosecution against the guilty people, because the times are unquiet, and we fear that there might be a new pogrom.

Dovid Moyshe Bogatin 8

Footnotes:

8 there may be slight differences in orthography, as concerns the identity of the witnesses, between the way the inquirer writes their names and the way they sign; for instance there maybe differences in the forms of given names or family names, written and oral form, or Hebrew, Yiddish and Russian forms (see : Moshe, Moyshe, Moshka, Moysey..) an so on ; there also may happen errors from the inquirers.

In general, the handwriting of the inquirers was very loose, with frequent confusions between the shapes of characters, so the spelling of family names is often difficult to ascertain, especially if they appear only once in the document

3

Hirsh Turchinskiy, hairdresser, living in the 1st district

On October 21st, about six o’clock in the evening, I was on Stavisskaya Street. I was standing with a small group of friends of mine, near the house, as it seems to me, of Turskenich . Between us and the soldiers who were on duty on Kievskaya Street, facing Stavisskaya Street, were hooligans - roughly one hundred people. One of my friends shot a fire in the air, to frighten the hooligans. So the hooligans ran towards the soldiers, and a part of them scattered. My friends and I, then, came to be before the fire-engine house. Suddenly I heard a salvo, and I saw that Udkherkiy and another of my friends had been wounded. Then, after maybe five minutes, I was wounded in three places: in my arm, in my shoulder, and in my shoulder blade. I remember very clearly that, except the shot in the air, which I previously mentioned, there were no other such ones. I remember that the soldiers did not give previous warnings, and did not fire blank shots. I remember that, when the salvoes were fired, there did not remain hooligans between the soldiers and us. I fear that there may be new pogroms, and, for that reason, I would not wish the raising of a criminal prosecution at the present time, because that could provoke new troubles.

Turchinskiy

4

Simkhe Tsion, lives at his mother’s

I personally saw the Fire Marshal, who was riding ahead of the hooligans and showed them which houses had to be plundered. Before his eyes they sacked a shop at the corner of Kievskaya and Vladimirskaya. On the following day, Saturday morning, I saw cans of food before the wall of the fire-engine house. Besides the Fire Marshal, I saw Police Inspector Lissovskiy, who also was riding ahead of the looters. Before me, at the corner of Kievskaya and Stavisskaya, he shouted:”[Orthodox] Christians, step aside!”, and, immediately after that shout, were fired three salvoes. Soldiers did not give warnings before firing. Just before the first salvo, a revolver shot in the air had been fired.

Illiterate 11

Footnotes:

9 The name Turskenich is confirmed, in the margin of the document, by another writer, who wrote it carefully.

10 in the vocabulary of the Russian Empire at that time, the words Orthodox and Christian are most of the time, for practical purposes, synonyms ; this is the case here, even if there is, for instance, a Catholic Church in the town.

11 illiterate (cannot sign his name), note of the inquirer

5

Moyshe Shmul Bondarovskiy, living in the first district

At six o’clock, on the evening of October 21st, I found myself on Vladimirskaya Street, in the midst of a mob of looters. In my presence, near Roydskuvit’s shop, Police Inspector Lissovskiy, wearing civilian clothes, at the head of a mob of looters, ordered: “come on, lads! go to it!” ; the shop was sacked. Then the whole mob, headed by Lissovskiy and by the Fire Marshal, came to Haas’s hat shop and was ready to ransack it. But Lissovskiy addressed them, saying : “Here there’s nothing but empty boxes, rubbish! The third shop is a good one!” The mob threw itself forward, except those who had entered Haas’s first shop and remained in it. When they came to Haas’s second shop; the first who broke open the shutters was the Fire Marshal, and he also was the first who entered the shop, with Shchekussutskiy. With them entered some thirty men. They started to grab goods and to throw them to the mob standing outside of the shop. At the same time, on the other side of the street, at Metropolis Hotel, a group of people headed by Shikhelman, an employee at the Indirect Tax Department, started to destroy a lamppost in front of the Hotel and a lamp in the doorway. Shikhelman invited them all to set the Hotel on fire, but they did not have the time to do that, because the Fire Marshal mounted again and rode to the Square, and Lissovskiy, having finished with the sack of Haas’s shop, started to run and follow the Fire Marshal, shouting to the mob: “Come on, boys, follow me!” They all threw themselves behind him, because they hoped to ransack and plunder all shops on the Square. But the mob was stopped by an Inspector of the 1st district. In my opinion, the total number of people who took an active part in the pogrom amounted to about 150 men. Among them were noticeable young boys and young men aged 18 -19 years.

Moyssey Bondarovskiy

6

Nikhum Goldenberg, living in the 2nd district. 12

At six o’clock, on the evening of October 21st, I was in my apartment, when I heard hubbub in the street, and I quickly went out. I saw a mob of looters, ransacking Uchitel’s shop, located on the other side of the street, nearly in front of mine. Then Gumovski, an employee at the Town Council, shouted to the mob: “Come on, lads! now, to Goldenberg’s shop!” (he meant my shop), and the Fire Marshal ordered: “With iron bars!”. On the spot were Police Inspector Lissovskiy, Police secretary Podgurskiy, the main secretary of the Town Council Ilkitskiy, and some others, all looking to the scene without taking part in it. From me have been stolen goods for a value of 600 roubles, and destroyed papers for a value of 1 500 roubles, I mean bills of exchange and IOUs that have been stolen. N. Goldenberg

Footnotes:

12 we do not know where was the limit between the urban districts, and we cannot be sure that the inquirers did not make mistakes on that point (for the preceding testimony, the inquirer had first written IInd district, and then scratched the second I.)7

Moyssey Horovits, master in locksmithing and mechanics, living in the 1st district

On October 21st, the house caretaker hurried to me, and told me that looters were going towards the Square. So I ran to Vladimirskaya, and I saw how Haas’s shop was plundered, and how people were destroying the lamppost at Metropolis Hotel. At the head of the hooligans were Police Inspector Lissovskiy, wearing his uniform, the Fire Marshal, the hairdresser Shekusutskiy, Shikhelman, and the schoolteacher Betani. The last-mentioned, with a little national flag in his hand, was terribly bustling about and shouting; you could see that a part of the mob followed his advices. After that, they all made a rush, following the Fire Marshal, towards the Square, but there an Inspector of the 1st district stopped them.

Then I hurried to Stavisskaya Street, where a huge troop (about 180 people) of looters was operating. At the corner of Stavisskaya and Kievskaya was standing a patrol of soldiers, under the command of an officer. A member of our self-defence group, willing to contain the looters, fired a shot in the air. Then the looters rushed towards the patrol, and a part of them dispersed. Not long after that, approximately ten minutes, we noticed a soldier, who was carrying a samovar taken from a jewish apartment; so we soundly thrashed him, and he started to shout that Yids were beating him. Then was heard a peremptory shout: “[Orthodox] Christians, step aside!”, and immediately after that shout were fired two salvoes, from which were wounded, among others, Turchinskiy and Bernshteyn. While I was taking Turchinsky away, hooligans threw themselves on me, beyond the bridge to Karakhtin13 , and started to strike me with clubs.

Afterwards I stayed all night long in the hospital, at the bedside of Bernshteyn, now deceased. He asked me to take revenge on those people, who savagely beat him on his way to the hospital.

Among the looters predominated common people, young boys, and all kind of rabble, that the police could have stopped without particular efforts.

Moyssey Horvits

Footnotes:

13 a precise knowledge of the urban geography of Mogilev-Podolskiy at that time, including the place where the Hebrew hospital was situated, would be necessary to check that part of the sentence

8

Moyssey Duvidsson, worker in a foundry of characters, living in the 2nd district.

On Stavisskaya Street, I was one of those people who protected the jewish lodgings, submitted to ransacking by the looters; those looters, in my opinion, were at most fifty people. The plundering took place in presence of a large detachment of soldiers, standing at the corner of Stavisskaya and Kievskaya streets. We fired 5 or 6 shots in the air, to frighten the hooligans. And, in fact, they hurriedly scattered. Among the plunderers was one soldier, carrying a samovar and a pillow. Suddenly, without any previous warning, but after a command: “Christians, step aside!”, were fired two salvoes with rifles, which killed several men.

On the following day, Saturday, when I came to the apartment of the now deceased Bernshtein, to fetch some belongings, a policeman and his patrol threw themselves on me and thrashed me.

M. Duvidzon

9

Mendel Kogan, locksmith

I saw Lissovkiy, indicating to the looters shops, which were immediately plundered. Then I hurried to Stavisskaya Street, where a mob of hooligans, numbering about 150 people, was looting apartments. We fired two salvoes in the air, and the hooligans ran off. Among them I noticed the schoolteacher Betani, and a soldier who was carrying a samovar and a pillow. We took those things from him, and he was soundly beaten. Then was heard a shout: “Christians, step aside!» and two salvoes were fired, from which among others was fatally wounded Bernshteyn. He was carried away to a nearby house, and, after that first move, two friends of mine and myself wanted to send him to the Jewish Hospital. As we were driving past a patrol of soldiers, looters threw themselves on us and started to beat us without mercy. My two friends, who were sitting beside me, ran away. As for me, having on my knees mortally wounded Bernshteyn, I did not want to leave him, and I tried to cover him with my own body, but the looters went on beating me, and pulled me out of the cab; they also dragged out Bernshteyn. Then I ran away. But I was stopped by two soldiers of the town military command, who searched me and seized my purse with my money. Just then some looters caught up with me, and wanted to finish me off. However, thanks to the assistance of Mr Kesselov (accountant _____ _____ _____ 14) who found himself there and could help me, I succeeded in going to the police station. There, police officer Voublovskiy, standing at the door, said: “Entrance here is not allowed to Yids”. Nevertheless, we went in. However, once we were inside, police officer Mandaburo refused to give me water to wash my wounds, saying: “No water for Yids!” The looters wanted to force their way into the station, so Kesselov and I were compelled to go out through the back entrance, to escape from them. Neither the soldiers nor the police officers wanted to provide any help either to me or to other victims.

Mendel Kogan

Footnotes:

14 there four words, added between two lines to explain the social position of Mr Kesselov; are written in small characters and are abbreviated, so that only the first one (bukhg. for bukhgalter = accountant) can be ascertained; the two following words could be abbreviations for social and for savings ; the last word is undecipherable)

10

Itsko Meshman, jeweller

When they plundered my jewellery, I stayed in the passage facing my house. I saw how the Fire Marshal was heading the pogrom. He shouted: “Hurry, boys!”. The plundering of the shop lasted half an hour, and all that took place before the eyes of a large number of onlookers. According to what was related to me by my master silversmith, Iossif Tinduss, and by my neighbour, Mordko Poyzner, two men, among other looters, took part in the plundering: Gumovskiy, an employee at the Town Council, and the hairdresser Shchekussutskiy.

Itsko Meshman

11

Khaim Gronzboym, owner of the Metropolis Hotel

Standing on the balcony of my hotel, I saw shops being plundered and ransacked on Vladimirskaya Sreet. At the head of the hooligans were the Fire Marshal, Police Inspector Lissovskiy, dressed in civilian clothes, Jan Shchekussutskiy, Gumovskiy, and Shikhelman. The Fire Marshal and Lissovkiy were the real leaders of the mob: they showed which shops to plunder; they gave the advice to leave apart the first Haas’s shop - in their opinion there were few goods in it, and they made the proposal of rather plundering his second shop. It was them who broke open the shutters, and they were the first ones who entered Haas’s shop. Lissovskiy lighted a lamp etc., other looters entered various shops and stores and stole goods. Shikhelman destroyed a lamppost and a lamp in my hotel, and proposed to set the hotel on fire; they were all asking where I was.

Beside the previously mentioned people, I also noticed Crime Investigator Bekhlemishchev and the Town Council member Khadji. The Crime Investigator stood before Tselik Marav’s fruit cellar, located in the same house as Haas’s shop 15 , and observed the pillage going on. They brought to him grapes, that he ate on the spot. Then they brought to him a basket full of grapes, a circular one, with a one pud 16 capacity, and he ordered to one of the hooligans to bring it to his house. I heard him saying: “Bring it to me home”, and the hooligan immediately headed for the Crime Investigator’s house. The C.I. was wearing his judiciary uniform, and everybody could see him. I had seen him before, during the day, in the manifestation, marching with a portrait of the Tsar.

As concerns Khadji, he addressed the workers who broke open the shutters of Haas’s shop, saying: “Hurry; boys, hurry!”. Those workers, as far as I know, were working on the building site of the Commercial Technical School, now in course of construction under supervision of that same Khadji, member of the Town Council. As far as I know, it was Khadji himself who called them to leave the building site, and to come first to the manifestation, then to the pogrom.

In the pogrom, there were half a dozen of policemen, who helped the looters to break the windows and the shutters. There were also two companies of soldiers, one near the Catholic Church, the other one near the Square, but neither one nor the other did stop the looters. Khaim Gronzboym

Footnotes:

16 one pud, equivalent to 16 kg (officially 16,38 kg)

12

Boris Drenziss, pharmacist

I saw Lissovskiy and the Fire Marshal marching at the head of the patriotic manifestation. Then they left the portraits of the Tsar at the fire-engine house, and the hooligans, headed by Lissovskiy, went to Stavisskaya Street, where they started to break the window glasses. The hooligans were followed by soldiers, under the command of an officer, and by some policemen, but neither the soldiers nor the policemen did hinder the hooligans from breaking the windows. In the evening, there was a pogrom on Stavisskaya street. From the jewish side were fired 12 or 15 revolver shots. Some people fired, who were not members of our self-defence force, which was very weak and unorganised. The soldiers fired two salvoes, without any previous warning. Immediately before the salvoes was heard a shout: “[Orthodox] Christians, step aside!”, and all the Russians 17 ran off. Four Jews were wounded.

Boris Drenziss

Footnotes:

17 it certainly is not necessary to recall that in the Russian Empire Russians and Jews were two different “nationalities” ; that belonging to one or another nationality was officially determined by belonging to one or another religion, for instance in the censuses

13

Leyzer Aronovich Gorenbeym, houseowner

In my presence, on the 21st of October, as the manifestation was passing near my house, the member of the Town Council Khadji addressed the Fire Marshal with these words: “Bring here as soon as possible the working class 18 which is working on the building site of the Commercial Technical School. The Marshal went off, riding, and after some time appeared some 50 workers, marching together along Vladimirskaya; they left the portraits of the Tsar on the grass and retraced their steps. At the head of the hooligans were the Marshal, Lissovskiy, Shikhelman, Gumovskiy and others. Lissovskiy threw off his greatcoat and remained with his jacket. The Marshal, Lissovskiy and Gumovskiy themselves broke the windows and the shutters, entered Haas’s shop and plundered it. Shikhelman undertook to break the lamppost at Metropolis Hotel and suggested to set the hotel on fire. There the policemen themselves participated in the sacking and in the smashing. On the Square there was a patrol, headed by Police officer Kubaevskiy; the soldiers smashed the window-glasses and took cigarettes, jars of marmalade and other products from Gitrelis’s shop. Leyzor Gorenbeym

Footnotes:

18 sic in the text. (Maybe, from the part of Khadji, an ironical use of the expression).

14

Mordka Poyzner, owner of a watchmaker’s shop

In my presence was plundered Meshman’s shop. Among the looters operating in the shop I noticed the barber Shchekussutskiy. The Fire Marshal was standing at the door and shouted: “Hurry, boys!”. He wanted them to operate faster, so as to go further to other shops. Illiterate 19

Footnotes:

19 remark written by the inquirer

15

Iossif Tinduss, master goldsmith

I saw how was plundered Meshman’s shop. Among the looters I noticed Shikhelman, Gumovskiy, Shchekussutskiy, and many other men whose names I do not know, but whose faces are well-known to me, because I already have been living in Mogilev a long time. I saw them rob things. I saw Shikhelman and Gumovsky cutting the fur off from the fur coats of Meshman and of his wife. They threw the outer covers in the street, and took away the furs with them 20. They also threw in the street the jeweller’s workbench. Then, when all went out of the shop, Lissovskiy and Shikhelman gave the advice of going to Zilberman’s shop. The Fire Marshal shouted: “Work faster!”

Tinduss

Footnotes:

16

Zissmya Stoler, tradeswoman in meat

I supply meat to Crime Investigator Bekhlemishev 21. He sends to me a servant with a written order, and, on the 20th of each month, I meet him at his home to settle our accounts. When I came to Bekhlemishev’s on October 21st, at half past three p.m., he came out to meet me, and reviewed his commands, according to which he owed me 26 roubles 22 . He gave me 10 roubles in cash, and went to his study, to write a global IOU for the remaining 16 roubles. When the C.I. came back with the written IOU and was ready to give it to me, his wife undertook to make him change his mind: she told that, anyway, on that day all the Jews would be slaughtered, and that they (she and her husband) 23 would have to clear off empty handed. Therefore, she started to demand that I give back the 10 roubles. Her husband joined her in her demand. Both 24 began to shout, to stamp their feet. I began to cry, asking them not to take back the money, all the more so as they had not paid all the sum owed to me. After a long wrangle, B. told me that, still and all, he would not give me any acknowledgment for the 16 roubles, then he added : ”if there is a strike, you will not get it; if there is no strike, I will give it to you next month.” I was compelled to go, without having received neither an IOU nor the 16 roubles, or even having taken back the notes for the previous commands that I had brought with me. After I had come back home, I related all those facts to my family, in presence of the worker Khaim Dreyger. Other people know about all that, for instance Mr Veyntraub, to whom I related everything, exactly as I relate the facts now. When I came to B’s home on November 20th, to get back the IOU [for the 16 roubles], and to settle the accounts and get paid for the previous month, the C.I. once again dreadfully lashed out at me; he called me names because I had told around me all the story of October 21st, he threatened me with hard labour. As concerns money, he paid me for October, and gave me the global IOU for 16 roubles that he had previously retained.

For her, illiterate, has undersigned, in her presence ------- 25

Gokhman 26

Footnotes:

22 very roughly calculated, an amount of 26 roubles in 1905 in the Russian Empire correspond to a monthly consumption of 50 kg of meat; but we have no idea of the composition of Bekhlemishev’s household, including family and servants; anyways, in the prevailing conditions of the time, this refers to a relatively affluent family

23 those two words have been inserted by the inquirer above the line, so it is difficult to guess whether they correspond to his own interpretation, or to the answer of the witness to a question about whom she meant by “they”. This insertion makes the sentence rather enigmatic, since we know what the behaviour of Bekhlemishev was during the pogrom, and can a priori think that he and his wife had nothing to be afraid of. Did B and his wife have to give proofs of their “mainstream” attitude?

24the inquirer has first written « she », then corrected into “both”

25that additive line is written in smaller characters, from another hand, the last word is undecipherable (jgs)

26 Gokhman has undersigned the declaration on behalf of the witness, who could not sign her name

17

Moyssey Gorovits

To complete my testimony I can add that in my presence was looted, on the Square, Kishenevskiy’s shop. Among the looters I saw Shchekussutskiy, Shikhelman, and Romassevich Tuznevechiy, rushing out of Kishenevskiy’s shop. Before that, they had broken open the shutters, and disorderly thrown outside the goods of the victim.

Moyssey Gorvits

18

Moshka Mednik, living in Nevissen’s house, on the Square

In my presence were ransacked Haas’s, Meshman’s and Kishinevskiy’s shops. I saw the looters who broke open the shutters, grabbed goods and took them out. Among other looters were. Shikhelman, Lissovskiy, the Station Master of Volgonets, Shchekussutskiy and Gumovskiy. I saw how someone handed an alarm clock to the Fire Marshal, who immediately threw it to the upper floor of the house.

Mednik

19

Vald Knekherg, master watchmaker

I was on the Square, standing on the sidewalk, and when the patriotic manifestation reached the Square, I wanted to join it, since Lasskin had invited me to do so. But when I came closer to it, the Station Master of Volgonets said to me and to other Jews: “You, scabby Yids, today we’re going to butcher you all!” Then I saw how were looted the shops of Haas, Meshman, Kishenevskiy, and others. The main participants in the looting were: the previously mentioned Station Master of Volgonets, wearing his uniform coat and uniform hat; Lissovskiy; the Fire Marshal; Shchekussutskiy, Gumovskiy, Shikhelman, and others Vald Knekherg Those men took with themselves many watches. The Fire Marshal and others threw many watches and clocks to the upper floor. I know the Station Master of Volgonets, because he was a regular customer at my shop 27

Footnotes: