|

|

KUPISHOK: The Memory StrongerPart 1

|

|

KUPISHOK: The Memory Stronger

Here, look. A picture: a thousand shrieking horsemen, their swords drawn, unleash their hatred against me and thirst for vengeance; don’t ask me why. To escape them, I feign death. Who are they? Crusaders of what faith? Cossacks in whose service? Frenzied peasants seeking what adventure, covered with whose blood? Alive I am their enemy; dead they proclaim me god. So, it’s for my soul’s sake, for my everlasting glory, that they repeatedly wish to destroy me and destroy my memory. But they don’t succeed. My memory is stronger than they are, they should know that by now. Kill a Jew and you make him immortal; his memory, independently, survives him. And his enemies as well. The harder they strike, the more stubborn the Jewish resistance. So, naturally, they are troubled. Puzzled by its convulsions, owed by its fits of delirious fire. Poor men. They are the players, but my memory governs the rules of their game. They regard themselves as hunters, and so they are; but they are quarry as well—and that they can never comprehend. Well, that is their problem. Not mine.

—Elie Wiesel, A Beggar in Jerusalem

THE SEARCH I am from Kupishok. I was not born there; I never lived there; I have never seen the place. But Kupishok is a part of my historical and cultural experience as a Jew, and it is the nexus with my more ancient source, Jerusalem. My great-grandfather lived in Kupishok; so did my grandfather and the other members of the Polin family. (My original family name is Polin.) My father and mother were married there, and my brother was born there; they emigrated to the United States, and here they died natural deaths. My father’s sister, Chena Polin, remained in Kupishok, married Shmerl Tuber and bore six children, five sons and a daughter, before she died in 1933. Hitler and his military and civil bureaucracy with the enthusiastic support of some of the local populations murdered eleven million people, six million of them Jews; one million of them Jewish children; four of them my first cousins in Kupishok. The mind becomes statistically numbed at the thought of millions of corpses. I was haunted by the ghosts of my cousins. What happened to the six Tuber children? What happened to them? Were they alive, did they die, how did they die, were they ghettoized, did they die in a ghetto, were they in a concentration camp, was their burial place in the sky? What happened to them? After my mother died, I found among her possessions a photograph of a young man and a woman, and on the reverse of the photograph a handwritten notation bearing the date, 1957. I believed it was a picture of one of the Tuber sons. He looked like me. In the early 1970s I began efforts to discover the fate of the six Tuber children, alive or dead. I contacted a number of international organizations, the International Tracing Service in Arolsen, Germany; United HIAS Service in Geneva; Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. And always the answer was the same: no record of the Tuber name. Not a trace. It was as though they had never been on earth. In 1975 I visited Israel and there I met, for the first time, a cousin—my mother’s niece, Sheva Fega, who had been born in Kupishok. A woman now in her 60s, she was a holocaust survivor whom we had encouraged to come to Israel some years before. During the First World War she had been a war refugee together with my mother, my brother and my mother’s brother—her father. Together now in her living room in Bnai Brak we began to watch family pictures. There was a problem. Sheva Fega had been deaf and mute since the age of three. She could not speak, could not write, and knew no international sign language. And yet we communicated—through her grown daughter—with hand movements, facial expressions, and with broken Yiddish. She recognized the picture I showed her of one of the Tuber cousins, and as best as I could understand she indicated that he was alive and living somewhere in Israel! A few days before leaving Israel that year I found a cab driver who spoke Yiddish and Russian, and together we found the office of the Russian language newspaper. There I arranged for an advertisement featuring the picture of the Tuber cousin. After I returned to the United States I received replies from cousins Josef Tuber and Ella Tuber Gendelis living in Israel, indicating that their father was also still alive and that their four older brothers had been killed in 1941. I could not find it in my heart to ask them for details, and they did not volunteer. By now I needed to know more—not only about the Tuber brothers, but also the rest of the Jewish population in Kupishok. For me the holocaust had focused itself in that small town in northeastern Lithuania. Who, what, where, when, how and why were the questions that nagged at me, never left me. In the ensuing years there were more advertisements in Russian, Yiddish and English language newspapers in Israel and in the United States. I began to receive some responses from Kupishok survivors. One came in the form of three pencil-written lines from a man in Brooklyn—a Rabbi who had been born in Kupishok—indicating that he had written a book in Yiddish, in 1951, about the destruction of the Jewish community in Lithuania and Kupishok. (I later found the book and the mention of Kupishok.) Another response came from a man whom I realized to be a cousin—eighty year old Yitzhak Polin, the son of my grandfather’s brother, a survivor not only of Kupishok but also of Dachau. In May of 1979 my wife and I travelled to Israel, and during a week in the Tel Aviv and Haifa areas we interviewed some of the survivors and recorded their stories. On the morning after our arrival in Tel Aviv, Yitzhak Polin came to our hotel and for the first time I met the cousin of whose existence I had only recently become aware. He walked feebly with a cane, and was accompanied by a younger woman, Yocheved Elisar. Our meeting was emotional; we kissed and held hands. Perhaps I was with my father again. This man knew my grandfather, his uncle, and my great-grandfather, his grandfather. He remembered my father only vaguely, but when I showed him a picture he recognized my mother, “Baila Gitke, the prettiest and most vivacious girl in Kupishok”. Until this moment he had believed that he was the only Polin left. He had had no children; his brothers, sisters, uncles—all dead. He had escaped from Kupishok, was captured and taken to the Kovno ghetto, later to Dachau. It was in the ghetto that he met Yocheved who later also survived a concentration camp, came to Israel in 1946, married Tzvi Elisar and raised two sons. After some years Yocheved learned that Yitzhak had survived and was living in Vilna; it was through her efforts that he was able to come to Israel in 1963. He lives in his own apartment in Herzliya. Yocheved looks after him much as a daughter would, makes certain that he eats regularly and is in comfort. We were together, the three of us—Yitzhak, Yocheved and I—a family. A Jewish family, closely a part of the extended Jewish family in the old sense, but happening in 1979. Later that week Israel and Ethel Trapido invited us to their home in Givatayim for an evening to meet with a few of the survivors of Kupishok. Israel was born in Kupishok, emigrated first to South Africa and then to Israel where he is an accountant. His family settled in Kupishok in 1816. The survivors gathered there in the Trapido home came, I believe, not so much to tell their stories as to meet this strange American Jew who had such as abiding interest in their beloved Kupishok and wanted to write a book about it. (Indeed, it was at this point that this narrative became a book instead of the letter originally intended to my two sons.) Why, they asked not sarcastically, are you interested in Kupishok and the events there? Why is an American Jew interested when their own children are not? I couldn’t tell why their children didn’t want to hear the story. I told them: ikh bihn a yid, ikh bihn oykh fuhn Kupishok. I am a slow thinker. I knew the answer I gave them was not enough, but I didn’t know what the correct answer was. I am not sure even that there is a correct answer—or any answer at all. Elie Wiesel writes, “Answers: I say there are none.” How then can I explain to them now? I needed to know the story and to tell it to someone. It started with the Tuber brothers who carried my bloodline. They were, the four dead ones: Yechiel, twenty-one, a recently ordained rabbi; Laibel, nineteen, and Pesakh, fifteen, tinsmiths like their father; and Berel, seventeen, a tailor. What happened in Kupishok in the summer of 1941, who were killed, who killed and how? Why? There needs to be a memorial to the Jews of Kupishok. Not because they or the events there were so unusual. Precisely the opposite—because it was so ordinary during that time of death in the heart of Europe’s Christendom. An American Jew, I and the rest of us failed to take to the streets to protest, to demonstrate, to march, to cry out to our President and to the leaders of the Allies of Silence that our people were being murdered. They knew it. If such a thing happened today, would we be silent again? Would they again offer no hope, no haven? There needs to be a memorial to the Jews of Kupishok because in 1967 when the Jews of Kiryat Yam, Bat Yam, Holon, Givatayim were openly threatened with annihilation, the world again stood by. Among those threatened Jews were the survivors of Kupishok that I met that May evening in the Trapido home. Left to themselves, they were to join the dead of Kupishok. And I, an American Jew of common ancestry with the Tuber brothers, would be left alive to write about another Jewish holocaust. Here, look. The truth: Hitler did not order the annihilation of the Jews immediately, without the realization that the world had given its permission. Even Hitler hesitated before the “final solution”; even he had to be convinced that there was no other choice. The Germans developed their anti-Jewish policy step by step, gradually, stopping after each measure to watch the reactions. There was always a respite between the different stages, between the Nuremberg laws and the Kristallnacht, between expropriation and deportation, between the ghettos and liquidation. After each infamy the Germans expected a storm of outrage; they were allowed to proceed. So they knew what that meant: we can go on. From 1938 to 1940 Hitler made extraordinary attempts to being about a vast emigration scheme. The world was divided between those countries who had room for Jews and would not take them, and Palestine which had room for Jews and was not permitted to take them. The Germans’ biggest expulsion project, the Madagascar plan, was under consideration just one year before the beginning of the killing phase. The Jews were not killed before the emigration policy was literally exhausted. And having started the killing, the Germans could never have succeeded in solving the Jewish Question with such speed and efficiency if it had not been for the help and tacit consent of the Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Slovaks, Poles, Hungarians. It was not by accident that the worst concentration camps were set up in Poland. Shmuel, a Tel Aviv cab driver, and I became friends. He had been a partisan. He told me that there were Poles who sold Jews to the Germans for two kilos of sugar a head. Historically, the Jewish tendency has been not to run from, but to survive with, anti-Jewish regimes. Jews have rarely run from a pogrom; they have lived through it. It is a fact that the Jews made an attempt to live with Hitler. In many cases they failed to escape while there was still time, and even more often they failed to step out of the way when the killers were already upon them. The Jewish reactions to force have been alleviation and compliance. It should be noted that the term “Jewish reactions” refers only to ghetto Jews. This reaction pattern was born in the ghetto and it died there. It is part and parcel of ghetto life. It applies to all ghetto Jews, assimilationists and Zionists, the capitalists and the socialists, the unorthodox and the religious ones. The Jewish reaction pattern assured the survival of Jewry during the Church’s massive conversion drive. The Jewish policy assured to the embattled community a foothold and a chance for survival during the period of expulsion and exclusion. If, therefore, the Jews have always played along with an attacker, they have done so with deliberation and calculation, in the knowledge that their policy would result in the least damage and injury. When the Nazis took over in Germany in 1933, the old Jewish reaction pattern set in again, but this time the results were catastrophic. The German bureaucracy was not impressed with Jewish pleading; it was not stopped by Jewish indispensability. Without regard to cost, the bureaucratic machine, operating with accelerating speed and ever-widening destructive effect, proceeded to annihilate the European Jews. The Jewish community, unable to switch to resistance, increased its cooperation with the tempo of the German measures, thus hastening its own destruction. It is seen, therefore, that both perpetrators and victims drew upon their ancient experience in dealing with each other. The Germans did it with success. The Jews did it with disaster. Elie Wiesel says that during the holocaust the traditional solidarity of the Jews broke into fragments. When Jews were persecuted in Germany, Jews in Poland thought: they don’t mean us. When Jews were massacred in Poland, Jews in France thought: they don’t mean us. When Jews were deported from France and Belgium and Greece and Hungary, Jews in America and Palestine thought: they can’t mean us. Perhaps for the first time in recorded history, Wiesel says, we missed the real intent of the enemy; he meant all of us. Those Kupishok survivors know all this, and they must have guessed the answer to their own question. This American Jew is one of Elie Wiesel’s madmen; he wants to create a memorial to an ordinary event. After the war the few Kupishok survivors drifted back and settled in Vilna, the traditional capital of Lithuania and now part of Poland. From there, through their own monetary and political efforts, they caused to be erected in Kupishok at one of the mass grave-sites a monument to the murdered Jews of Kupishok. The monument does not bear the word “Jew”, not does it bear the names of the murdered. Only a vague reference to the victims of Hitlerish aggression. The story contained in this small volume is not unique; it was repeated hundreds, thousands of times in the shtetls, villages and towns of the Jewish settlement of Eastern Europe. The monument in Kupishok bears no names. In this book are only a few of the names of the Jewish men, women and children murdered in Kupishok. The names will never be known of those who died along with their relatives and friends with no one left to remember them. Socialists or capitalists, Zionists or non-Zionists, religious or irreligious, mad or sane, good or bad, all those who remained in Kupishok in June 1941 died together. This book is a memorial to them, named and unnamed. These few pages of paper are all they have, all that is left.

Arizona, U.S.A., August, 1980

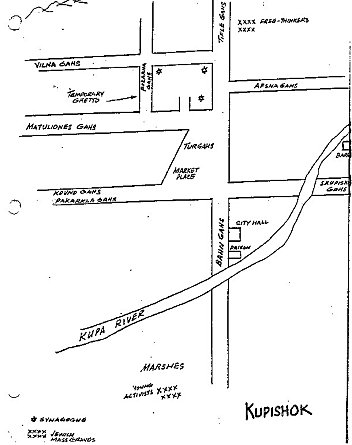

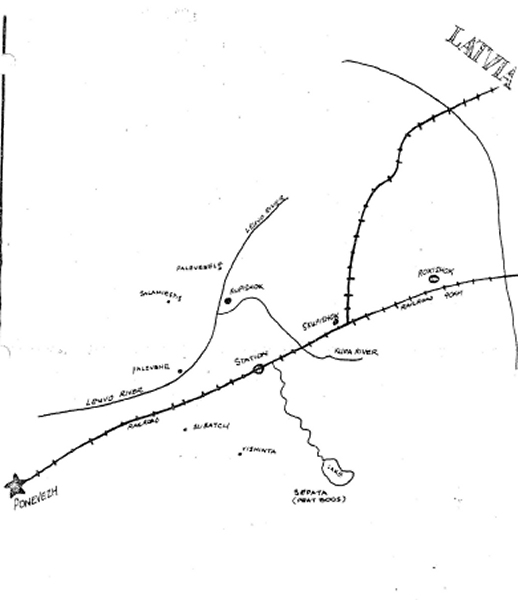

KUPISHOK Kupishok (in Lithuanian, Kupiskis) is an old town in northeastern Lithuania, situated between the Levuo River and its left tributary, the Kupa, which curves from the east to the south of town. About two kilometers south of Kupishok is a station on the railway which runs from the city of Ponevezh (Panevezys) northeast to the border with Latvia, about 70 kilometers from Kupishok, and then east across the Russian border. Still farther south somewhat, beyond the railway line, is the Shepata peat bogs. Surrounding the town is thick forest and farm lands, interspersed with tiny church-villages and farm-villages. Historical sources mention Kupishok from 1510 onwards; Jewish settlement began more than 300 years ago, evidenced by grave markers in the Jewish cemeteries dated in the seventeenth century. The first member of the Trapido family came to Kupishok from Holland in 1816, and the Polin family was already there. In the eighteenth century the town and the surrounding area belonged to the Tyzenhaus (Tiesenhausen) family of magnates and later to the Prince Czartoryski. In 1817 its population was 3,742 of which 2,661 were Jews. During World War I, in May 1915, most of the Jews left Kupishok to become war refugees, and only part of them returned there after the war. During the ensuing years many of the Jewish youth emigrated to South Africa and to Eretz Israel. Nevertheless, by 1941 about 3,500—perhaps 4,000—people lived in Kupishok including 400 families of Jews who lived mainly in the center of the town and approximately an equal number of Christians who lived in the area surrounding the core. Relations between the two groups had always been peaceful; there is no historical record of a pogrom there until June-July 1941. Kupishok was one of the few towns in Lithuania with a considerable community of Hasidim. There were two officiating rabbis in 1941, the Hasid, Rabbi Israel Noah Khatzkevitz, and the Mitnagid, Rabbi Zalman Pertzovsky. The community had three synagogues, a yeshiva, a talmud torah, and three schools (Yavneh, Tarbut and a Yiddish school). Many of the Jewish children attended the secular Lithuanian high school (the gymnasia) and the public school for lower grades. In the center of Kupishok was the Turgahs, the Market Place, and from it radiated the main streets. The street north was Tifle Gahs (Church Street) on which stood the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, built by King Sigismund Vasa. South from the Market Place ran Bahn Gahs (Train Street), also called officially Gediminas Street after the fourteenth century King of Lithuania. A small bridge carried the Bahn Gahs over the Kupa and to the train station. On this street was the city hall and the town jail, very near to the Kupa before the bridge, the houses of the Polin, Shavel and Sneierson families. The Sneierson house, at number 49 Gedeminas, was across the street from the city hall. Nearby was a small hotel or inn, the Viesbutis. On the east side of town, on the other side of the Kupa not far from the Hasidic cemetery, was a small barracks (kazarmis) and firehouse. Adjoining the Market Place at the northwest was the area of the synagogues next to which was a small street, Pozarna Gahs which ran the short distance from Matuliones Gahs to Vilna Gahs. Pozarna Gahs become the temporary ghetto for a few weeks in the summer of 1941. At 5:30 on the morning of Sunday, June 22, 1941, Reichsminister Josef Goebbels announced on German radio the Wehrmacht attack against the U.S.S.R. across the borders of the buffer states. The line of invasion extended from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south, the area in which was the main concentration of the Jewish population of Europe. Later that morning the Lithuanian revolt against the Russians began in Kovno and on Monday, in Berlin, fifty enthusiastic Lithuanians raised the flag of their country. From East Prussia the Fourth Panzer Group (Commander Hoppner) of the Northern Army Group under General von Leeb thrust toward Kovno and Shavli in Lithuania; by Tuesday, June 24, the Lithuanians were in full revolt and the independence of Lithuania was proclaimed. On the same day Kovno and Shavli were taken, and the Nazis were on the road north to Riga in Latvia. On the twenty-fifth fighting was reported between Lithuanian insurgents and Russians in Vilna. By Friday, the twenty-seventh, the German main forces had driven north of Kovno and around to Vilna in the east. On July 2 Riga was captured, fighting was taking place east of Minsk—Vilna far in the rear—and by Friday, July 4 the Germans were engaged in mopping-up operations in all three Baltic states. On June 23, 1941, Einsatzgruppe A joined the German forces on the northern front. Wednesday, June 25, Einsatzkommando 3 of Einsatzgruppe A reached Kovno which had been captured the previous day, and elements of Ek 3 were already beyond the city and approaching Kupishok. Some families, perhaps eighty, fled Kupishok upon the approach of the Germans, some to neighboring small villages to seek shelter with Christian peasants as had been done during the First World War. Others continued in their flight, hoping to reach the Russian border. Most of the Jews remained in Kupishok where they were subjected to persecution by their Lithuanian neighbors as soon as the Germans entered the town. Later all the Jews who had sought shelter in out-lying farms together with those Jews who lived in small villages surrounding Kupishok were brought into the town to join the Jewish population in the temporary ghetto set up in Pozarna Gahs—a short street—and in the adjoining synagogue yards. All this area was surrounded by barbed wire. The two rabbis, Zalman Pertsovski and Israel Noah Khatskevits were taken into the Hasidic synagogue where they were burned to death and then buried in a cemetery for “unbelieving” Christians. The wife of Rabbi Pertsovski, Chaya Leah Pertsovski, with her children found refuge for a time in the old Doctor Frantskevitch’s house. Six weeks later they were all betrayed and killed. Nahum Shmid, the richest and most philanthropic Jew in town, hid out for two months in a nearby village, Shmilg, until his money was used up. He was then betrayed also, brought to the municipal jail and shot. By September, 1941, about 3,000 Jews were murdered in Kupishok. So far as is known, no Jew who remained in Kupishok after Wednesday, June 25, 1941 survived. Perhaps 200 people, from 47 families, survived and were from the small group who fled Kupishok before the Germans arrived. Some of those who fled initially could find no refuge and returned to Kupishok to die; a few others were captured and taken to other ghettos as was Yitzhak Polin who survived the Kovno ghetto and Dachau concentration camp. In 1979 he was living in Israel.

Yechiel Tuber as a student in the Yeshiva Bet-Rubenstein, Ponevezh, Lithuania. Rabbi Tuber was killed shortly after his ordination, age 21.

A THOUSAND SHRIEKING HORSEMEN

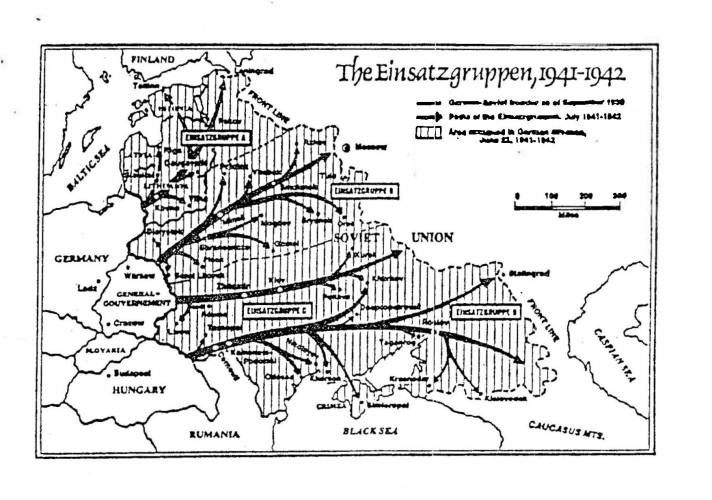

When the German Wehrmacht attacked the U.S.S.R., penetrating first the buffer states on June 22, 1941, the invading armies were accompanied closely by small mechanized killing units of the SS (Schutzstaffeln, “Protection Squad”) and police which were technically and tactically subordinated to the army field commanders but who were really free to go about their special business of killing. These mobile killing units operated in the front-line areas under a special arrangement in a unique partnership with the German Army, and were called Einsatzgruppen (special-duty groups). Earlier, Adolf Eichmann had become concerned with the problem of the annihilation of Jews who lived in remote territories. The “solution of the Jewish question” was his responsibility. The foremost problem was that of geography, and Eichmann had already experienced difficulties in this connection. Transporting men, women and children in railroad trains and trucks require an extensive and complicated personnel system of guards, engineers, firemen, interpreters, and so on. Railroad trains were needed to move troops; trucks were required to haul food, ammunition and all the materials of war. Something had to be done to avoid the necessity of shipping Jews from distant Lithuania, Estonia, Romania, the Ukraine and the Crimea to the concentration camps in Germany, Austria and Poland. Eichmann pondered and finally arrived at what he considered to be a satisfactory solution. For those populations that could not be taken to the executioners, the executioners would go to the populations. Indeed it would be a waste of locomotive power and gasoline to transport people long distances just to kill them. Besides, there would be the expense and trouble of feeding them, sheltering them, and guarding them from escape before the mass executions. It was decided to kill them where they were to be found. No long waits, no costly maintenance of prison camps with barbed wire, guard towers, blood-hounds and electricity-charged fences. All that was to come later, when the human numbers became too great and shooting became too inefficient. Eichmann conferred with Himmler and Himmler conferred with Hitler. Eichmann’s recommendations were accepted and the Einsatzgruppen organization was born. Thus, in early 1941, Himmler, Heydrich and Eichmann were directed to recruit mobile bands of executioners which were to accompany and follow the German armies as they overran the Eastern territories, killing all Jews there as soon as any region or community was cleared of enemy opposition. Himmler removed all doubt as to the object of the Einsatzgruppen: “It is not our task to Germanize the East in the old sense, that is, to teach the people there the German language and the German law, but to see to it that only people of purely Germanic blood live in the East.” The Einsatzgruppen training program began in May, 1941, with three thousand men. The assembly points for the Einsatzgruppen personnel and the four weeks of training were the Border Police School Barracks in Pretzsch, Saxony and the neighboring villages of Dueben and Schmiedeberg. The organizational strengths were: an Einsatzgruppe equal to a battalion, an Einsatzkommando or Sonderkommando equal to a company, and Teilkommando equal to a platoon in strength of numbers. There were four Einsatzgruppen organized to work eastern Europe. Einsatzgruppe A operated in the three Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and in northern Russia eastward to Leningrad. Eg A was commanded by SS-General Walter Stahlecker and later by Heinz Jost who had specialized in law and economics at the Universities of Giessen and Munich. Stahlecker was killed in the war; Jost was later tried at Nuremberg and sentenced first to life imprisonment which sentence was later reduced to ten years. (At his trial he testified that he did not remember ordering any Jews to be shot.) Eg B operated south of the area of Eg A, and eastward to Moscow, commanded by Arthur Nebe. Eg C worked in most of the Ukraine and was commanded by Otto Rasch, a Doctor of Law and Economics. He was held for trial at Nuremberg but was separated from the rest of the defendants because of an illness from which he died in 1948. Eg D ranged in the territories of the southern Ekraine, the Crimea and the Caucasus. Its commander was SS-Major General Otto Ohlendorf, a graduate in law and political science from the Universities of Liepzig and Goettingen, and a one-time practicing barrister in the courts of Alfeld-Leine and Hildesheim; tried at Nuremberg, he was sentenced to death and hanged. As the operations progressed, each sub-Kommando leader reported to his Kommando leader the results of the day’s actions at the end of each day, and then the totals were transmitted to the Eichmann Gestapo headquarters for distribution of the Nazi hierarchy. The original Einsatzgruppen reports were found in Eichmann’s headquarters after the war and were translated for the Nuremberg trials. The Einsatzgruppen were to be permitted to operate not only in army rear areas but also in the corps areas right on the front line. This was of great importance to the Einsatzgruppen, for the Jews were to be caught as quickly as possible. They were to be given no warning and no chance to escape. The operational units of the Einsatzgruppen were the Einsatzkommandos (“striking force”). Pogroms are short, violent outbursts by a community against its Jewish population. In its tactics the Einsatzgruppen endeavored to start pogroms in the occupied areas (and not infrequently such orders were anticipated by the local populations). The reasons which prompted the killing units to activate anti-Jewish outbursts were partly administrative, partly psychological. The administrative principle was very simple: every Jew killed in a pogrom was one less burden for the Einsatzgruppen. A pogrom brought them, as they expressed it, that much closer to the “cleanup goal” (Sauberungsziel). The commander of Eg A, Stahlecker, in one of his reports complained that the Jews “live widely scattered over the whole country. In view of the enormous distances, the bad conditions of the roads, the shortages of vehicles and petrol, and the small forces of Security Police and SC, it needs the utmost effort in order to carry out shootings.” The psychological consideration was more interesting. The Einsatzgruppen wanted the population to take a part—major part—of the responsibility for the killing operation. “It was not less important, for future purposes,” wrote Brigadefuhrer Dr. Stahlecker, “to establish as an unquestionable fact that the liberated population had resorted to the most severe measures against the Bolshevist and Jewish enemy, on its own initiative and without instructions from German authorities.” So the pogroms were to become a defensive weapon with which to confront an accuser, or an element of blackmail that could be used against the local population. As soon as war had broken out, anti-Communist fighting groups of Lithuanians had gone into action against the Soviet rear guard. In Kovno, the newly arrived Security Police approached the chief of the Lithuanian insurgents, the journalist Klimaitis, and persuaded him to turn his forces on the Jews. This he did with considerable enthusiasm and after several days of intensive pogroms Klimaitis had accounted for 5,000 dead: 3,800 in Kovno, 1,200 in other towns. For the killing units the Lithuanian anti-Soviet “partisans” who had been engaged in the pogroms became the first manpower reservoir. Before disarming and disbanding the partisans, Einsatzgruppe A picked our “reliable” men and organized them into five police companies. The men were put to work immediately in Kovno. In September a Lithuanian group attached to Einsatzkommando 3 swept through the districts of Rasseyn (Raseinyai), Rakishok (Rokiskis), Sarasi, Perzai, and Pren (Prienal), killing all Jews found in this area. The total number of victims accounted for by Einsatzkommando 3 with Lithuanian help was 46,692 in less than three months; that is, from late June to September, 1941. By the end of October, 1941, 80,311 Jews had been killed under the direction of Einsatzgruppe A, and by December another 56,110 souls had been added to the count. From the report of Brigadefuhrer Stahlecker covering the activities of his Einsatzgruppe A from the beginning of the war against Russia until October 15, 1941: “…Partisan groups formed in Lithuania and established immediate contact with the German troops taking over the city (Kovno). Unreliable elements among the partisans were weeded out, and an auxiliary unit of 300 men was formed under the command of Klimaitis, a Lithuanian journalist. As the pacification program progressed, this partisan group extended its activities from Kovno to other parts of Lithuania. The group very meticulously fulfilled its tasks, especially in the preparation and carrying out of large-scale liquidations.” “…Pogroms, however, could not provide a complete solution to the Jewish problem in Ostland. Large-scale executions have therefore been carried out all over the country, in which the local auxiliary police was also used; they cooperated without a hitch…” At the climax of the mass shootings of Jews there were eight Lithuanians to every German in Stahlecker’s firing squads. Since the Jews were not prepared to do battle with the Germans and their assistants, one might ask why they did not flee for their lives. Some Jews were evacuated by the Russian authorities, and many fled on their own, but this should not obscure a phenomenon: most Jews did not leave. They stayed. People do not voluntarily leave their homes for uncertain havens unless they are driven by an acute awareness of coming disaster. In the Jewish community that awareness was blunted and blocked by psychological obstacles. First was the prevailing conviction that bad things came from Russia and good things from Germany. The Jews were historically oriented away from Russia and toward Germany; Germany, not Russia, had been their traditional place of refuge. During October and November of 1939 thousands of Jews streamed from Russian occupied Poland to the German sector and the flow was not stopped until the Germans closed the border. Similarly, one year later, at the time of Soviet mass deportation in the newly occupied territories, the Germans received reports of widespread unrest among Ukrainians, Poles and Jews alike. Almost everyone was waiting for the arrival of the German Army. When that Army finally arrived, in the summer of 1941, old Jews in particular remembered that in the First World War the Germans had come as quasi-liberators. These Jews did not expect that now the Germans would come as killers. Another factor which blunted Jewish alertness was the haze with which the Soviet press and radio had shrouded events across the border. The Jews of Russia were ignorant of the fate that had overtaken the Jews in Nazi Europe. Soviet information media, in pursuance of a policy of appeasement, had made it their business to keep silent about Nazi measures of destruction. The consequences of that silence were disastrous. From a German intelligence report of July 12, 1941—Report of Sonderfuhrer Schroter enclosed in Reichskommissar Ostland to Generalkommissar White Russia, August 4, 1941: “The Jews are remarkably ill-informed about our attitude toward them. They do not know how Jews are treated in Germany, or for that matter in Warsaw, which after all is not so far away. Otherwise, their questions as to whether we in Germany make any distinctions between Jews and other citizens would be superfluous. Even if they do not think that under German administration they will have equal rights with the Russians, they believe, nevertheless, that we shall leave them in peace if they mind their own business and work diligently.” But also the extreme closeness of living family ties among eastern European Jews condemned many to their death. To take flight meant abandoning parents, children, and wives, living like a hunted animal in the forest with no hiding place anywhere and haunted always by the guilt of flight. Those who did escape from the edge of the killing pits were often denounced by anti-Semitic partisan units. Many were driven to return to the old ghetto or seek out a new one when life in the wilderness became unbearable; either meant certain death. Therefore, a large number of Jews stayed behind not merely because of the physical difficulties of flight but also, perhaps primarily, because they had failed to grasp the danger of remaining. That means that precisely those Jews who did not flee were less aware of the disaster and less capable of dealing with it than those who did. The Jews who fell into German captivity were the old people, the women, the children and the naïve. They were those who were physically and psychologically immobilized. The mobile killing units soon grasped the Jewish weakness; they discovered quickly that one of their greatest problems, the seizure of the victims, had an easy solution. Those Jews who did flee, who had taken to the roads, the villages, and the field had great difficulty in subsisting there because the German Army was picking up stray Jews and the population refused to shelter them. The Einsatzgruppen took advantage of this situation by instituting the simplest ruse of all: they did nothing. The inactivity of the Security Police was sufficient to dispel the rumors which had set the exodus in motion. Within a short time the Jews flocked into town. They were caught in the dragnet and killed. The Germans and their auxiliaries were able to work quickly and efficiently because the killing operation was standardized. In almost every city and town the same procedure was followed, with minor variations. The site of the shooting was usually outside of town, at a grave which may have been specially dug or were deepened anti-tank ditches or shell craters. The Jews were taken in batches, men first, from the collecting point to the ditch; the killing site was supposed to be closed off to all outsiders. Before their death, the victims handed their valuables to the leader of the killing party. In the winter they removed their overcoats; in warmer weather they had to take off all outer garments, sometimes underwear as well. Some Einsatzkommandos lined up the victims in front of the ditch and shot them with submachine guns or other small arms in the back of the neck. The mortally wounded Jews toppled into their graves. There was another procedure which combined efficiency with an impersonal element. This system has been referred to as the “sardine method”. This way the first batch had to lie down on the bottom of the grave. They were killed by cross-fire from above. The next batch had to lie down on top of the corpses, heads facing the feet of the dead. After five or six layers, the grave was closed. The leaders of the mobile killing units even as they directed the shootings, began to justify their actions and to repress the language of their reports avoiding such expressions as “kill” or “murder”. The terminology which they used was designed to convey the notion that the killing operations were only an ordinary bureaucratic process within the framework of police activity. Various euphemisms were invented to express their activities: disposed of, liquidated, area freed of Jews, processed, special treatment, taken care of, area purged of Jews, the Jewish question solved, finished off, treatment in a special way, treated accordingly, actions, resettlement, cleansing, elimination, executive measure. The commanders of the Einsatzgruppen constructed various justifications for the killings. The significance of these rationalizations is apparent since the Einsatzgruppen did not have to give any reasons to Heydrich, their overall commander; they had to give reasons only to themselves. Generally speaking, the reports contained one pervasive justification for the killings: the Jewish danger. This fiction was used again and again, in many variations. In the area of Einsatzgruppe A (Lithuania) Jewish propaganda was the justification. “Since this Jewish propaganda activity was especially heavy in Lithuania,” reads a report, “the number of persons liquidated in this area by Einsatzkommando 3 has risen to 75,000.” There was a rationalization which was focused on the Jew: the conception of the Jew as a lower form of life. Generalgouverneur (of the occupied territories) Hans Frank was given to the use of such phrases as “Jews and lice”. In the terminology of the killing operations the conception of Jews as vermin is quite noticeable. Dr. Stahlecker, the commander of Einsatzgruppe A, called the pogroms conducted by the Lithuanians “self-cleansing actions” (Selbstreiningungsaktionen). It should not be supposed that the Einsatzgruppen leaders were uneducated, course barbarians. Among the twenty-three such defendants at Nuremberg were men who were graduates or educationally specialized in law, economics, history, banking and dentistry. Among their civilian professions: University professors, architect, clergyman, union administrator, voice teacher and opera singer, importer and linguist, civil service administrator, business man and civil servant. Only one had been a police officer, another an intelligence officer. Nor were these killers forced to remain in the gruesome business they had chosen. Kommando leaders who demonstrated themselves incapable of performing cold-blooded slaughter were assigned to other duties, not out of sympathy or for humanitarian reasons, but for efficiency’s sake alone. During the Nuremberg trials, SS-Major General Otto Ohlendorf, Chief of Einsatzgruppe D, declared that he forbade the participations in executions of men who did not “agree to the Fuhrer-Order”, and sent them back to Germany. Another witness, Albert Hartel, of the German Security Police in Kiev, testified that SS-General Eugen Thomas, commanding Einsatzgruppe C at the time, “passed on an order that all those people who could not reconcile with their conscience to carry out such orders, that is, people who were too soft, as he said, to carry out these orders, should be sent back to Germany or should be assigned to other tasks. Thus at the time a number of people, also commanders, were sent back by Thomas to the Reich just because they were too soft to carry out the orders.” There is no record of severe punishment befalling such individuals nor, indeed, of any punishment at all. In fulfilling Hitler’s program every Nazi official saw for himself a higher rank, a gaudier uniform, an easier and more lucrative post. Vanity, arrogance, and greed were the vehicles in which the Nazi leaders traveled the highway of criminality and inhumanity. The Einsatzgruppe officers had an additional reason for preferring their assignments: it saved them from hazardous combat services. No one shot back. In the front lines one faced an armed and aggressive opponent; in a foxhole one could expect any moment a fragmentizing artillery shell. But on the Einsatzgruppe field of combat there were no foxholes. There were only long ditches in front of which one’s adversaries helplessly stood to await the fire which they could not return. These were the “technically competent barbarians”, as Dr. Franklin H. Littell calls them, available to the highest bidder. Dr. Littell writes, “The common mistake is to suppose this is solely a result of his avarice or unbridled ambition; it is aided and abetted by a system of education that has trained him to think in ways that eliminate questions of ultimate responsibility. Having eliminated God as an hypothesis, he exercises godlike powers with pride rather than with fear and trembling … The worst set of crimes in the history of mankind was engineered by Ph.D.’s and committed by baptized Christians.” As the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg in 1947 twenty-three defendants were charged with one million murders. One was released, another separated from the trial of the others because of poor health. Of the remaining twenty-one, fourteen were sentenced to death, two to life imprisonment and the other five to lesser prison terms. Upon later review, two of those sentenced to prison were released on time already served and the other five were given new terms reduced in years. Of the fourteen sentenced to death, nine sentences were commuted. Five were hanged. WHO ARE THEY? I have indicated the involvement of the parts of the Lithuanian general population in the killing of Jews, my sources taken from books written on the activities of the Einsatzgruppen, the killing units, and the destruction of East European Jewry. As will be seen this activity is corroborated in the testimonies of survivors of Kupishok and of other towns in Lithuania. As would be expected, the Lithuanian community in the United States presents a somewhat different picture to make the claim that the Lithuanian people in toto are not guilty of genocide. To that end a pamphlet has been published (1977) by the Lithuanian American Community, Inc. of the United States entitled “Towards An Understanding of Lithuanian-Jewish Relations” which consists of an introduction by The National Executive Committee and a reprint of the article Jews in Lithuania which appears in the second volume of Encyclopedia Lituanica (pp. 522-530). Excerpts from this pamphlet follow. Introduction “… The Lithuanian people do not claim exemption from this loathsome sociological phenomenon (i.e., genocide against European Jewry—SM). Yes, several score Lithuanians participated in the machine-gunning of Jews in Lithuania and Belorussia.” “… At this juncture the Lithuanian American Community of the United States wishes to point out one salient argument: anti-Semitism of a virulent brand is not endemic to the Lithuanian people. While it is historically accurate that, following the collapse of the first Soviet occupation of Lithuania (1940-1941) a number of individual acts of reprisal were committed against Lithuanian and Russian Communists, Jews and gentiles, nonetheless the Lithuanians did not engage in wholesale atrocities against the Jewish population. The Nazi records captured by the Allies point out that the person and property of local Jews and Poles became the exclusive concern of the German occupation authorities. Local Lithuanian civil authorities had no say in the treatment of Jews, Russians, and Poles.”

Jews in Lithuania “… Jews … were disproportionately strong in the most profitable occupations. The Jews owned 77 percent (over ten times their quota) of the country’s commerce, 22 percent of its industry, and 18 percent of its communications and transportation lines.” (The writer refers to the period between the two World Wars—SM). “From 35 percent to 43 percent of the country’s physicians and over 50 percent of its lawyers were Jews. Located in the urban centers, Jewish businesses dominated the face of the country’s cities and towns. Excited by their newly gained status, they rendered it even more conspicuous by making their business signs and door plates in Yiddish, along with an occasionally quite ungrammatical Lithuanian translation. Most Jewish businessmen chose to keep their establishments closed on Saturdays and open on Sundays. Quite a few Jewish enterprises felt entitled to use Yiddish in their bookkeeping, which made the books inauditable by most tax inspectors.” “The Lithuanians, those of the young generation particularly, were excited by the regained independence of their country, and they were impatient to see their country acquire an appearance like that of the long-established European states. Instead they found the most visible parts of the country’s face looking ‘like a kind of Judea’, and some of them became irritated. Their resentment burst into a campaign of ‘cleaning the face of the country’ by smearing Yiddish language signs and placards with tar. Local authorities claimed that they were unable to protect all the signs from this patriotically inspired vandalism, and ordered (in July 1924) replacement of the bilingual signs with ones drawn in Lithuanian only … The Sunday Rest Law (1924) was prompted by the same consideration.” “… The Tragic End. The end of Lithuania’s independence proved to be the beginning of the end of Lithuanian Jewry. At first, apparently because of the role of Jewish apostates in the previous community underground, a conspicuous number of Jews emerged in key positions of the Soviet regime, installed in Lithuania following the Russian invasion of June 15, 1940. This, however, did not preserve the Jews from the blow inflicted on the entire population of Lithuania by radical measures of Sovietization. Like everybody else, they were ruined economically by sweeping expropriation of enterprises, properties and savings. All their cultural institutions, organizations, and newspapers were shut down, and their prominent leaders were jailed along with the other alleged ‘enemies of the people’. Eventually, in the course of the following months of the communist regime, the Jews seemed to be adjusting themselves somewhat more easily to the new conditions; at least such an impression was increasingly taking hold in the minds of the rest of the population. This impression was strengthened when the Jews were but little affected by the mass deportations staged by the troops of the NKVD in June 1941. The thought of Jews as being the masterminds behind the communist terror had been held only by a few up to that time, but now it caught on and spread among people surprised, shocked, and enraged by the stroke of deportation. Only rumors promising the imminent German march against Soviet Russia stirred up hope for rescue from the raging NKVD terror. It was in such a state of mind that the popular uprising against the communist regime broke out in Lithuania simultaneously with the German attack of June 22, 1941, only a week after the most shocking NKVD raid. The insurgents fought retreating Russian troops from two to four days in advance of the oncoming German ground forces, and they also fervently hunted down civilian functionaries and helpers of the collapsing regime, most of whom were retreating eastward along with the Russian troops, while some were in hiding, a few even sniping back from their improvised shelters. Most Jews stayed home in anxiety, but several thousand of them appeared on the roads, looking for some way to escape imminent Nazi persecution by trying to mix into the columns of Russian and local procommunist civilians who were being evacuated. In many instances the insurgents pursued their vendetta against the communists injudiciously, so that innocent people fell victims in executions without trial, solely on the grounds of unchecked suspicion or denunciation. Though this action, which lasted no longer than two days in any particular area and ended altogether on the fourth day of the war, was explicitly aimed at communist activists, not at Jews as such, the Jews, especially those on the roads or in homes suspected of being used by communists for shelter, were particularly prone to fall under suspicion in the circumstances. Consequently an unknown number of Jews were killed along with an equally unverified number of non-Jews, guilty and innocent …” “… the SD, having found the Lithuanian insurgents uncooperative in the drive against the Jews, had banished any armed partisan activities in the area and had ordered the surrender of all weapons in possession of the insurgents. The label ‘partisans’ was fraudulently pinned on gangs of mercenaries lured by the SD into ‘auxiliary units’ hurriedly set up for the purpose of helping the Germans in their alleged task of clearing the area of ‘residual hostile elements’. Only a few of the insurgents (less than one out of every thousand) volunteered to join the ‘auxiliaries’, most of them with little anticipation of the precise nature of their involvement. Some opportunist collaborators of the communist regime, having failed to escape, hastily squeezed themselves into the ‘auxiliaries’ seeking safe disguise and new opportunities for themselves. The rest of the ‘auxiliaries’ were attracted from the obscurest layers of the population, including adventurers of low morality and common criminals at large, greedy for loot promised in return for the unscrupulous execution of bloody assignments.” “… In several weeks of sweeping operations, the SD detachments, aided by the ‘auxiliary units’, achieved almost total annihilation of Jews in all the provincial towns of Lithuania, and by the end of August 1941, the entire territory of Lithuania was reported in Berlin to be ‘clear of Jews’, except Vilnius, Kaunas, and Siauliai, the three largest cities, where, after several sporadically staged assaults, about 70,000 Jews were left alive but confined to the ghettos established there …” So says the Lithuanian American Community, Inc. of the United States.

|

| Click here to continue reading Memory Stronger, Part 2 |