CONTENTS

CLICK ON ITEM TO DISPLAY

Manvesty - Massacres and Monuments

Footnotes: Kulchiny Ghetto & Murder

Monument at the Manivsti Forest

* * *

by David Winer

Kulchiny was one of thousands of small shtetls that dotted Eastern Europe and the Pale of Settlement. Tucked in amongst the expansive rolling wheat fields of Ukraine, it was an isolated microcosm of Jewish Shtetl life. Accessible, even today, only by an unpaved dirt road, it’s isolation kept its Jewish inhabitants closely bound for survival in a hostile gentile environment. Every impulse to romanticize the shtetl must be resisted, it was poor and quelled any real sense of hope, growth and expansion. Hence, many of its inhabitants left to America or other large Russian cities. But, for Kulchiny’s inhabitants it was their home: snug, predictable, reliable and an existence that relied upon decades of tradition and religious beliefs. Most of Kulchiny's Jews were small-scale traders, craftsmen or artisans. Their local market thrived and was the envy of the local villages. the The Kulchiny Jewish population grew from a mere 177 souls in 1765 to 2,031 in 1897, when it was at its height. At that time they made up 47% of the population.

I

try to imagine how my grandfather, Pinchas (Benjamin) Winer, felt in

1910, when as a 20-year old, he left Kulchiny all alone to go to

America. What were his thoughts as he watched his family, home and

village fade away in the distance, as the wagon bumped along the dirt

road? Was he hopeful, afraid, resilient, determined, etc? I will never

know, but surely he would never have imagined the fate of his Kulchiny

shtetl just 32 years later.

After the Holocaust, Jewish life in Kulchiny had ended, totally erased. Not one Jew returned and, like its brethren shtetls scattered across Eastern Europe, it was obliterated on every level. That small isolated village was a microcosm of the utter severity and barbarity of the Holocaust. Encouraged by the Germans, the local Ukrainians eagerly assisted in the destruction of their neighbors. The current Ukrainian villagers no nothing of the contributions, history, or fate of the Jews of Kulchiny. All that remins of the rich Jewish history is a singleover-turned gravestone and two old houses,

Below, you will learn how the many centuries of Jewish life in Kulchiny came to an abrupt, methodical, violent, and thorough end.

* * *

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June, 1941, more than 100 Jews (about 20 families) were evacuated from Kulchiny to the east and some Jewish men were drafted into the Red Army. About 400 Jews including 40 craftsmen remained at the start of the occupation.

In early July 1941, troops of the German Sixth Army occupied Kulchiny. In July and August 1941, the German military authorities appointed a village elder (starosta) and recruited an auxiliary Ukrainian police force. In September 1941, authority was transferred to a German civil administration. Kulchiny became part of the Krasilov Region, in Gebiet Antoniny, within Kommissariat Wolhyn und Podolia. German Harald Schorer became the Gebietskommissar in Antoniny.

The anti-Jewish Actions in Gebiet Antoniny, which included Kulchiny, were organized in 1942 by officials of the Security Police outpost (Aussenstelle) in Starokonstantinov, headed by SS-Hauptscharführer Karl Grafii assisted by the chief of the Gendarmerie, Karl Otto Pauliii. The head of the Ukrainian police in Antoniny was named Galitzky.

In the summer/ fall of 1941, the German authorities implemented a series of anti-Jewish measures in Kulchiny. The Jews were ordered to wear distinctive markings, first in the shape of the Star of David, and later patches in the shape of a yellow circle, sewn on their clothes. In addition, they were required to perform arduous manual labor, prohibited from leaving the limits of the village, and subjected to robbery and humiliation by the Ukrainian police.

In late 1941 or early 1942, Gebietskommissar Schorer issued an order posted in public places to establish ghettos in Bazaliia, Krasilov, and Kulchiny. The Jews were ordered to move to one of these places, where they would be confined to a specific quarter ghettoiv. Shortly afterward, a ghetto was established in Kulchiny, consisting of about 25 houses. The Jews were made to erect the barbed-wire fence themselves. The Jewish houses outside the ghetto area remained empty or were pulled down to make room for the fence or for other purposes. Initially there was no permanent guard around the ghetto, but the Jews were afraid to go into the village, as this was prohibited. According to one account, some Jews escaped from the ghetto; those who were caught were shot by the German security forces. The Jews were also forbidden to converse with the local Ukrainian population.

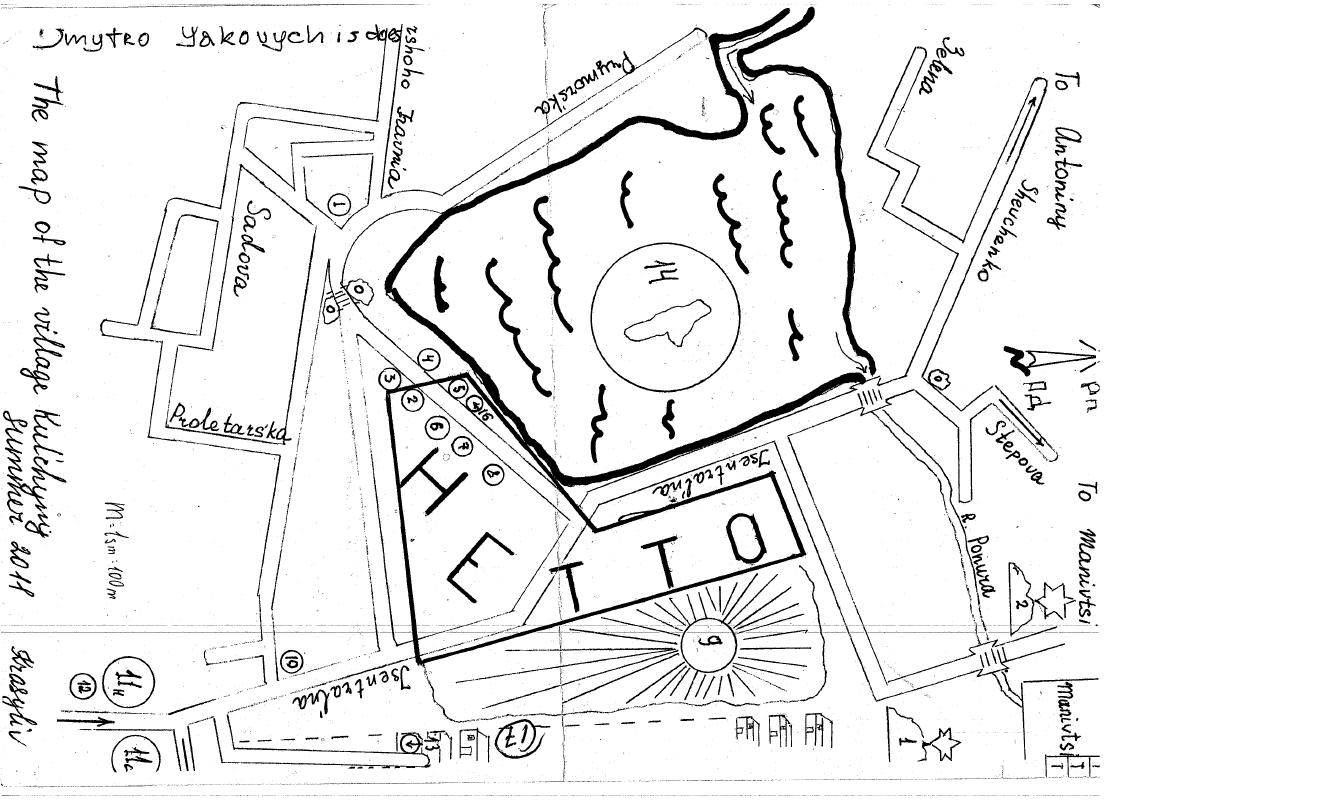

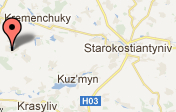

THE KULCHINY GHETTO (HETTO) and MAP KEY

From time to time, the Germans and Ukrainian police came to Kulchiny and escorted groups of Jews to perform forced labor, such as road work in Antoniny or other places. The Jews received no rations, but lived on whatever they could get from the local Ukrainian population. The Germans and local police humiliated the ghetto inhabitants in every conceivable way. When they were forced to dismantle their houses and load the materials onto carts for transport to Antoniny. Jews and even young Jewish girls were forced to take the place of the horses that ordinarily pulled the carts. The precise number of Jews in the ghetto is not known, but it was about 400 or 500, probably including some brought in from nearby villages such as Kuzmin.vi

Sometime around the end of May 1942, part of the Jewish population from the ghetto was resettled into a labor camp based in a stable in the village of Orlintsy, close to Antoniny, where they worked repairi roads and performing other tasks.vii

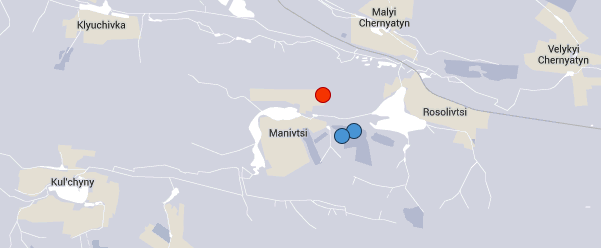

In July 1942, the ghetto in Kulchiny was liquidated. Members of the German Gendarmerie and the Ukrainian police from Gebiet Antoniny surrounded the ghetto and escorted the roughly 60 remaining Jews to the village of Manivtsi. Those unable to walk were loaded onto carts. In Manivtsi, many of the Jews of the Gebiet were collected, before being taken out and shot, including those from the Orlintsy camp. Initially the Jews from Kulchiny were held overnight in a stable in Manivtsi, while a mass grave was being built. On the following day, once the grave was ready, the Jews were transported in trucks to a nearby wood.viii

More, at a later date: http://www.yahadmap.org/manivtsi-khmelnytskyi-ukraine/village-170

As they were being unloaded, a local resident of Manivtsy recognized the Jewish teacher Solomyonnaya from Kulchiny, who used to teach his son. She was pulling her hair out and she shouted to a local policeman that she was a teacher; she tried to show him a document, but the policeman knocked her to the ground with a blow to the head from his rifle buttix.

The

Jews were lined up alone the edge of the grave, roughly 20 meters long

by 4 meters wide. A German SD man shot them into a pit Two Jews

who attempted to flee were shot dead as they ran. There were probably

several such mass shootings organized here by the Security Police and

the SD unit based in Starokostantinov as successive groups of Jews

arrived in Manivtsi. The Ukrainian police was responsible for escorting

the victims before the shootings and for cordoning off the killing site.x About 200 Jewish craftsmen from the Krasilov ghetto, together with some other Jews still held at Manivtsi, were shot on the grounds of the estate in Manivtsi in September 1942.xi

After the Jews had been removed from the Kulchiny ghetto, the Gebietskommissar took over responsibility for the empty houses. Most were dismantled, and the materials taken to Antoniny and used by German officials as firewood. The local Ukrainian authorities sold a few houses for local residents to live inxii. There were very few survivors of the Kulchiny ghetto.

The above material is from The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Volume II, Ghettos in Eastern Europe, G. Megargee, Editor, Article authors: Alexander Kruglov, Martin Deantrans, and Steven Seegal. Documentation of Kulchiny Jews is located in the following archives: BA-L (II 204 AR-Z 442/67) DAKhO (R863-2-44) GARF (7021-64-793); VHASH (# 30137); YVA (M-33). The footnotes are below.

* * *

KULCHINY

“The Germans occupied Kulchiny in mid-July 1941. Together with the Germans, members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) arrived in the town and immediately began to mistreat and rob Kulchiny's Jews. In the spring of 1942 Jews from Kulchiny and the surrounding villages were put in a ghetto. Jewish "elders" and Jewish guards were appointed. The Jews were ordered to wear distinctive patches on their clothes. They were not only forbidden to have any contact with non-Jews, but were also beaten, humiliated, and forced to perform hard labor.

"... in [the] spring of 1942, they established a ghetto surrounded by barbed wire. Jews from nearby small villages were concentrated in the ghetto, a leader was appointed, and Ukrainian guards were stationed there. Jews were forbidden contact with non-Jews and were sent out for forced labor.

"In August or September 1942, the Jews were gathered in the marketplace and escorted to the village of Manivtsi, where they were housed overnight in stables and pigsties. With the exception of a few artisans, all were shot in pits in a forest located near the Manivsty village. The artisans were shot at the same place about a month (or several days later, according to other sources) . Kulchiny was liberated by the Red Army in March 1944.”

The Yad Vashem Enclycopedia of the Ghettos during the Holocaust, Editor in Chief Guy Miron, Co-editor Shlomi Shulhani\Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 2009

More information about Kulchiny, from the Yad Vashem Archives can be found at: http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/search_results.asp?cx=005038866121755566658%3Auch7z5rmfgs&cof=FORID%3A10&ie=UTF-8&q=Kulchiny&sa=Search&siteurl=www1.yadvashem.org%2Fyv%2Fen%2Fabout%2Farchive%2Findex.asp&ref=www1.yadvashem.org%2Fyv%2Fen%2Fholocaust%2Fresource_center%2Fitem.asp%3FGATE%3DZ%26list_type%3D3-0%26TYPE_ID%3D132%26TOTAL%3D%26pn%3D4%26title%3DUkraine

* * *

THE MANIVTSI FOREST KILLINGS (Excerpt from the From Yad Vashem Website)

“In July 1942 about 3,000 Jews from various villages were shot to death or buried alive in the Manivtsi area. The villages were Kulchiny, Krasilov, Antoniny, Bazaliya, and Orlinsty - all of Krasilov County”. On September 21, 1942, which was Yom Kippur (in August, according to other sources), early in the morning German gendarmes and Ukrainian policemen from the town of Antoniny arrived in Kulchiny. All the Jews were driven out of the ghetto to the market square. They were told that they were being taken for work. Those unable to walk were loaded onto carts; the rest were formed into a column and all of them were taken to a forest near the village of Manivtsi, about 10 kilometers from Kulchiny. Those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. Some mothers tried in vain to save their children. At the murder site the Jews were locked into cowsheds and stables overnight. The next day the Jews were taken to a large pit (which some of the Jews had been forced to dig) and ordered to undress and enter the pit. Then they were shot.About a month later (or several days later, according to another source) the Jewish artisans who had been spared during the initial massacre were taken to Manivtsi Forest and shot. Estimates of the number of murder victims range from 150 to several hundred.”

The photo, below, was taken at another Nazi "pit massacre". The Kulchiny Jews were force marched to the Manivsty Forest. There, they were made to undress and enter the pit. Then, they were shot.

* * *

SIMA SLUTSKAYA - MANIVESTY MASSACRE

Sima Slutskaya, was born in Kulchiny on Wednesday, April 27th, 1921. The video interview of her shows photographs taken in 1944, in which she, and surviving Jews from Krasilov and surrounding towns, and people from nearby villages visited three mass graves located in a forest near Manvesti village. Those graves hold the bodies of the Jews from Krasilov and Ku'chiny, and other nearby towns who were murdered by the Nazis in the summer of 1942. Sima recounts that she too had been taken to be shot but managed to escape; most of her family were murdered at the site. Sima died on Friday, February 21st, 2014 in New York State. She is survived by a son, Gregory Slutskiy of Albany NY.

(Published at the Yad Vashem website on Apr 8, 2014)

View a video of Sima being interviewed at the Manvesty Massacre site:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_e9ps3zxrvE&feature=youtu.be

* * *

Kulchiny

Kulchiny, Krasilov County, Kamenets-Podolsk District, Ukraine

Jews began to settle in Kulchiny around the beginning of the 18th century. Most of Kulchiny's Jews were small-scale traders or artisans.

In the 1920's a Jewish rural council

(selsovet) and a Yiddish school were established in Kulchiny. In the

mid-1920s about 1,200 Jews lived in Kulchiny, comprising 39 percent of

the total population. However, during the following years many Jews

left Kulchiny for large Russian cities or went to other countries.

The Germans occupied Kulchiny in mid-July 1941. Together with the Germans, members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) arrived in the town and immediately began to mistreat and rob Kulchiny's Jews. In the spring of 1942 Jews from Kulchiny and the surrounding villages were concentrated in a ghetto. Jewish "elders" and Jewish guards were appointed. The Jews were ordered to wear distinctive patches on their clothes. They were not only forbidden to have any contact with non-Jews, but were also beaten, humiliated, and forced to perform hard labor.

On September 21, 1942 (in August, according to other sources), all inmates of the ghetto, with the exception of artisans, were murdered near Manivtsi village. The artisans were shot at the same place about a month later (or several days later, according to other sources).

Kulchiny was liberated by the Red Army in March 1944.

Manvitsi Forest

Manvitsy Forest Courtesy of Herb Bixhorn

On September 21, 1942, which was Yom Kippur (in August, according to

other sources), early in the morning German gendarmes and Ukrainian

policemen from the town of Antoniny arrived in Kulchiny. All the Jews

were driven out of the ghetto to the market square. They were told that

they were being taken for work. Those unable to walk were loaded onto

carts; the rest were formed into a column and all of them were taken to

a forest near the village of Manivtsy, about 10 kilometers from

Kulchiny. Those who tried to escape were shot on the spot. Some mothers

tried in vain to save their children.

At the murder site the Jews were locked into cowsheds and stables overnight. The next day the Jews were taken to a large pit (which some of the Jews had been forced to dig) and ordered to undress and enter the pit. Then they were shot. In about a month (or several days later, according to another source) the Jewish artisans who had been spared during the initial massacre were also taken to Manvitsy Forest and shot there. Estimates of the number of murder victims range from 150 to several hundred.

Commemoration of Jewish Victims

After the war a monument was erected at the site of the mass murder of Kulchiny's Jews. The black stone bears an inscription in Russian that says: "Eternal memory to the victims of fascism. 1942." There is no reference to the Jewish origin of the victims.

The Yad Vashem 'Untold Stories' site may be visited at: http://www1.yadvashem.org/untoldstories/database/murderSite.asp?site_id=225

* * *

A PERSONAL STORY

My sister says that she had heard that my father's sister, Golde Bleifer Kfare, was buried alive in the pit and that she and a friend managed to escape. We did not know how what happened after that, but did hear that she had died. My sister considered naming her 1st son, Jon, after Golde but our father did not want that since he didn’t know for sure that she had died. My sister's 2nd son, Gary, was named after Golde; by then my father had gotten word of her death.

I remember sitting at a Hollywood Florida Chinese restaurant with my wife, Deanna, and my sister, Sair, and her husband, Eli Wilks. My daughter, Tracey, was pregnant and my sister was curious about what would be the name of the new baby. She told me that when Gary was born, she wanted to give him the middle name Blafer, and she asked our dad if anyone in his family had a name beginning with a 'B'. He told her that he had an uncle, Baruch. Gary's Hebrew middle name is Blafer. The first letter of the middle name, 'B', is the English connection to Baruch.

About a year later, after my lunch with Sair, Edward Berkovsky, husband of Rita Bleifer Berkovsky, who resided in Israel, was researching the Kulchiny Bleifer family and had found my name on a genealogical research site. He contacted me. We compared stories and memories about the family. I told Edward the story about Baruch and Gary. It turned out that Baruch was Rita’s grandfather. He had left Kulchiny as a young man and moved further west in Ukraine, in an area not occupied by the German army.

Both Edward and Rita and I shared similar stories about our Kulchiny family roots. There is no doubt that Rita's grandfather was my father's uncle and that she is my second cousin.

The clincher story we shared was the one about my father's great-grandfather. He was a ‘banker’ - providing the Russian farmers with seeds and supplies in the spring and selling their crops in the fall. After the crop sales, the Russian farmers paid him for his services. Our great-grandfather was killed by a highwayman as he returned from a trip after selling the farm crops. His son, our great-grandfather, Leizer, was only three years of age at the time. The grandfather, after whom my middle name was taken, lived to be 103 years old. Happily, Rita and her family were able to relate even more stories to me about Leizer and his children.

My wife had written some notes about an interview she had with my dad several years earlier (When I had no interest in family genealogy). She had noted that Leizer, who lived in Kulchiny, had six sons - Nissen, Shimon (emigrated to the US), Raza, Jacob, Baruch, and Yeedl. Leizer was wealthy and he set up all of his sons in business; not all the businesses were in Kulchiny. One owned an inn and was shot dead in it. I have no information on the others, knowing that there may have been other sons. There were at least two sisters - Leah and Riva. One married Jacob Reznik (there were several intermarriages with Bleifers and Rezniks). The Rezniks emigrated to Argentina. One of their children became a dentist. The dentist and his wife visited the US in the 1950's but none of my US relatives remembers anything about them.

Many of our relatives lived in towns other than Kulchiny. Arranged marriages, work opportunities, politics, etc. were reasons to move. Some of the cities that our family lived include Starokostiantyniv, Hriciv (Ritziv), Krasiliv, Osipil, Antoniny, Lyubar, Berdychiv, Provwaloivka and, surely, others.

Rita Bleifer Berkofsky's grandfather moved to Dneiperpetrovsk from Kulchiny when he was young. That was far enough west so that the Nazi's didn’t get there. He was in the Russian army but his family remained in Dneiperpetrovsk. Rita gave me names of many of our relatives killed by the Nazi's. Several othe descendants of Baruch also survived the war.

* * *

These statements are from interviews conducted in the 1970’s by the Soviets. They were made in response to a request from West German authorities after they opened investigations against German police and civilian authorities who perpetrated the Holocaust in occupied Soviet territory. They were taken by Russian investigators and sent to the West German authorities. Due to the delayed timing of these efforts, there were few prosecutions and most cases were closed as the German suspects, by then, were dead, too ill to stand trial, or in many cases, the evidence was not sufficient to meet the very stiff German legal requirements for a murder case. Far more Ukrainian collaborators were punished than Germans. Unfortunately, the most culpable Ukrainian collaborators knew what to expect, so they left the Soviet Union and did not return.The German investigation files are located in the Ludwigsburg Archives.

these statements, when the witnesses use of the word Police, it denotes Ukrainian collaborators called Schutzman (gendarmes). The German soldiers and the SD (German Security Service) officers were primarily responsibility for the creation and destruction of Jewish ghettos in occupied Eastern Europe.These witness statements were provided by Dr. Martin C. Dean, Research Scholar, US Holocaust Memorial Museum, mdean@ushmm.org, (202) 488-6119.We also want to acknowledge our great appreciation to Ellis Levin for his translation.

- - - -

Donna Moskaliuk

Born

1893 in Kultschiny. Statement Date: March 21, 1973

I was life-long resident of Kultschiny. During the German occupation my

house was adjacent to the ghetto the Jews were forced to build. I was

separated from the ghetto by a street. In spring 1942, the ghetto was

surrounded by barbed wire that the Jews were forced to put there. At

first there was no guards but the Jews were afraid to leave the

ghetto as it was forbidden. Jews were forbidden to work or interact

with the Ukrainian population. The ghetto had about 25 houses. The

other Jewish houses outside the ghetto were vacant. Some Jews were

led to work at times by the police to Antoniny and other places. No

food or other provisions were given to any of the Jews. They got

whatever the villagers gave or sold to them. Ghetto dwellers were

scorned by the police and other participants. In the beginning there

were about 400-500 people. Besides the Jews of Kultschiny, there

were other Jews from surrounding villages brought during there from

Kuzminy and Nikoljev.

- - - -

Michail Moskaliuk

Born 1908 in Kultschiny. Statement Date: March 21, 1973

I am a lifelong resident of Kultschiny. During the occupation I lived here and was commander of the local village police until Sept 1941. Before the occupation our village was 1/3 Jews. They owned around 150 homes and the Ukrainians owned 300. At the beginning of the war around 20 families left and evacuated to the east. The rest remained and other Jewish families from surrounding villages were put into the ghetto. There were about 400 Jews in the ghetto, with about 40 artisans among them. The ghetto was built early spring 1942 and was fenced off by the Jews themselves and consisted of 25 houses near the present business "selpo" (co-op). The barbed wire was nailed directly to the walls of the houses. Jews were forbidden to work or socialize with the population. There were no guards outside the ghetto. Shoemakers were taken at times to work in Antoniny, staying the week and returning on Sunday. Also part of the men did road work on Starokonstantinov road. Some Germans or police came to fetch them.

The Jews were there for about only 3 months. In the ghetto no provisions were provided to them and they lived from what they got from the villagers. About July 1942, I was told by the Brigadier of the area to get my wagon ready to be a driver to Manivsti. There were nine other wagons, six German police and also many Ukrainian police from the area. I only knew the German Commissar of the area, Gerhard Friedrich, the most senior in rank. He ordered the Jews to form a column. Those who could not walk, children, aged, sick were put on the wagons. The column went to Manivsti about 7 km away. We arrived at 1:00pm. The Jews were unloaded near the military supply area and put into horse stalls. I missed what happened to them as I went home. The German Fiedrich accompanied the Jewish column with the police. He was in a light carriage and stayed with the police in Manivsti when the wagons left. From the behavior of the police I knew what was in store for these people. I later heard that all were shot in Manivsti. I know nothing of the circumstances surrounding the killings as I had already left.

- - - -

Nikolai Krawtschuk

Born

1896 in Manjewzy (Manivsti). Statement Date: March 15, 1973.

During

the occupation I worked in Manivsti. In the summer 1942 the Jews were

beginning to be assembled in the camp on the edge of Manvisti. The

camp was 2 horse stalls in the military support area. Citizens of

Kultschiny, Krassilov and Orlinzy were brought there. Twice I saw the

column of Jews going to the camp. My house was separated from the

camp by the river, but I could see it well. Both horse stalls were

filled with people. In early July 1942 at about 6:00am I saw a column

of 30 Jews with shovels going toward the forest, led by 3-4 armed

police. At about 10:00am later that day a wagon loaded with Jews, one

of which I recognized was my sons teacher named Solomanaya from our

village school. She was born in Kultschiny. She turned to the armed

police tearing her hair and screamed she was a teacher, and held out

a document. The policeman hit her with a baton and she fell to the

bottom of the wagon. I figured they were off to be shot as such

rumors were around the village. After seeing the first wagon, I went

home, as I could not stand the awful sight. After the first

shooting, only the Jewish artisans and their families were left in

the camp. In Sept.-Oct. 1942, I saw the mass graves behind our

village; one on the edge of the Manivsti forest by the silo ditch

that was dug in spring 1941. I remember the dimensions, as I was a

digger; it was 20 meters long and 4 meters wide. The second mass

grave was inside the forest at a clearing. The remaining Jewish

artisans were shot at that area. I cannot say anything as to the

identity of the shooters and guards who participated, as I did not

recognize any of them.

- - - -

Dennis Paska

Born 1888 in Manjewzy (Manivsti). Statement Date: March 13, 1973

During the occupation I was working road construction in the area. I lived on the street and about 300meters from my house near the military supply area were two horse stalls and a two story hayloft. In the summer 1942 a camp was built there to hold the Jews. Their column marched past my house. I saw 5 or 6 columns, accompanied by Ukrainian mounted police. All the Jews were put into the stalls, not given any food provisions and no one was released from the stalls. There was no fence and the Ukrainian police guarded the camp. I do not remember if any Germans were guards.

Mass executions started about four days after the arrival of the first group. Three to four wagons came into the camp on the day of the shootings: The Jews were led from the stalls to the wagons, at about 9:00am. Upon leaving the stalls, people threw their outer clothing onto a heap. The wagons went past my house, over the embankment of the pond into the village center and then toward the forest. Armed police were each wagon. That night the Brigadier of the road crew ordered me and 3 other crew members to the silo ditch that was previously dug on the edge of forest east of Manivsti. We were ordered to fill in and cover the ditch. We saw that the ditch was filled to the top with corpses from the Manivsti camp. The ditch was 20 meters long, 4m wide, about 3m deep. I don't know how many corpses. It is hard for me to imagine such numbers. No police or Germans were still there. We noticed no signs of life in the ditch. All the corpses were dressed in underwear only and were evenly placed in the ditch. I did not look for wounds on the victims. Around the ditch I did not observe any expended shells or other military items. We finished covering the ditch by the time it was dark.

Later I learned another execution took place in Manivsti forest. I don't know if wagons transported people anywhere there. Until Sept. 1942 about 200 Jewish artisans, remained alive in the camp. They were shot on the edge of the camp. I saw this shooting from my house. On the day of the shooting Germans came with the local police. I do not know how many, maybe three Germans and the rest Ukrainians. The Jews were led from the horse stall and aligned in two dense rows. A German with a sack went up and down the rows collecting items from the Jews. One Jew was hit with a baton. The Jews then got undressed and were led to the old cleaned up silo ditch; several groups were formed and then I heard shots. I was too far away to see who did the shooting as people around the ditch blocked my view. My wife and I feared for our lives and hid in a stall and did not witness the entire event. The shootings lasted no more than 2 hours. I do not know who covered the grave filled with bodies. I do not know the names of any participants. After the war all three murder sites in the area of Manivsti were identified with memorials, still standing up to the present.

- - - -

Dennis Pjotr Doschtschuk

Born 1924 in Grizenki.Statement Date: December 18, 1972

I was in Antoniny during the occupation working as an agronomist. The area commissariat was formed in the area in Antoniny in the fall of 1941. When the Soviet army arrived I was sentenced to jail after I served the sentence, I returned to my parents' place, in Kultschiny.

The Jews were confined to the ghetto most of their houses outside the ghetto were confiscated and disassembled. The conditions were very hard as space was limited. In houses previously inhabited by one family now 20 people were housed and movement was limited. Later on guards were stationed around the ghetto because before the guards the Jews who had no food bartered with local people around the area. The guards then eliminated this. I observed the building of the fence in Kultschiny and saw the German military there. I did not know any of the Germans that were overseeing the building of the ghetto. I saw the Germans with the Ukrainian police drive the Jews from surrounding villages to the Kultschiny ghetto.

In the summer of 1942, the Jews from the ghettos of Kultschiny were taken to Manisti and shot. I did not witness the shooting but rumor was that the entire ghetto population was shot. It was said, the executioners were SD Germans from Starokonstantinow brought to Manivsti. I don't know any names of these people nor how many were killed.

Q: Can you say anything about the crimes of persons from the ranks of the Germans?

A:. Scherer gave the order for the ghettos as the area commissar, he was the superior to all other officials of the German administration. During the occupation I did not have direct communication with Scherer in my business with the occupation authorities. He had a Deputy Schweigert.he looked to be about 35 years old. He spoke broken Russian. Before the war he was concerned with agriculture: a farmer probably. When everyone fled, he set off to the west. The German Scherer (first name unknown) born about 1900 and wore a brown officers uniform. He did not speak Russian. He was executed by partisans in one of the villages in the summer of 1943.

- - - -

Wassilij Lyssink

(Ukrainian Policeman) , Born 1920 in Grizenki. Statement Date: February 1, 1973

During the German occupation I lived in Antoniny until June 1942 . Previously I worked in the agricultural cooperative of my home village of Grizenki. I joined the police in Antoniny and for some time was the local commander. I worked there until January 1944 then fled until the Soviet army arrived. There was not a ghetto in Antoniny, but there were Jews employed by the police as shoemakers, tailors and barbers.

The Kultschiny ghetto was established before I joined the police. I don't know when it was built. The ghetto was several one storey houses with barbed wire. In the summer of 1942 the police chief of Antoniny commanded me and other policeman to take the seven Jews employed in the Antoniny back to the Kultschiny ghetto. We took them in a wagon to Kultschiny and met the highest ranked policeman. He ordered the seven Jews into the Ghetto and for us to guard the ghetto from 10:00 pm until 9:00am.

The next morning about 10 wagons arrived and one coach with several local police and four Germans. The order was given to encircle and cordoned off the area. I was on the bridge over a spot in the river close to the ghetto. I saw the police and gendarmes drive the Jews from the ghetto and force them onto the wagons. We accompanied the convoy of Jews to Manivsti village.

About 2:00pm we came to Manivsti village and the Jews were locked in a horse stall located on the edge of the village. There were already many women, children, men and old people in the shed. The police guarded the shed and I do not know if any German soldiers were there. I only saw Ukrainians. After my partner and I had brought the Jews from the ghetto at Kultschiny we went to rest in a shack and slept until morning.

About 8:00 am two wagons came to the stall and several police went in and led out about 30 young Jewish men and loaded them onto the wagons and drove away. One of the wagons returned a little later. The police led 10 more Jewish men out of the shed and I was ordered to transport these Jews. Our wagon came to the edge of the forest, near the village of Manivsti. I saw about 60 Jews already digging a big ditch and the Jews we brought were also put to work digging. Near the ditch was the head of the Germans named Paul and four other Germans and two SD members from Starokonstantinow. We were ordered to cordon off the area around the Jews who were digging the ditch. Twenty police formed the chain. I was about 3 meters from the ditch. After an hour a wagon with about 15 Jews arrived, including women and children. The German Paul and two SD members told the gendarmes to bring the Jews to the old half of the ditch. The Gendarmes pushed them into the ditch and the SD man and shot the Jews. I don't know if the Jews were standing or laid themselves on the bottom of the ditch. They were undressed before the shooting. He shot only using pistols. After 2:00pm the other ditch that the 40 Jewish men had dug was ready. It was 20 meters long, 7-8meters wide and about 2m deep.

The same SD man who shot the 15 Jews in the first ditch then went over into the new ditch and ordered the 40 diggers to the far edge of the ditch, and shot them all with a pistol which was being reloaded for him. I don't know if he ordered the Jews to lie in the ditch or if he shot them standing. They began to transport by wagons the remaining Jews from the stalls. The shooting went like this: After the arrival of the wagon, the gendarmes ordered them to undress by the ditch. Five Jews at a time were forced into the ditch that was occupied by the SD members. They ordered the Jews to lie face down. The SD man shot them one after another in the back of the neck, standing upright, extending his shooting arm. He shot the entire population from the shed and used a pistol while the other police in the ditch reloaded the clips.

I do not know how many Jews were killed; but the ditch was filled 1m deep with corpses of children, women, men, and old people. All were shot by the SD man who was stocky, medium height. The second SD who did not shoot had an average build and was heavy. The Ukrainian policeman in the ditch who held the clips, was average build and was born in Krassilov. During the execution, an 8 or 9 year old tried to flee but the police shot him and threw the corpse into the ditch. A 30-32 year old man tried to flee but suffered a head shot by Paul, and then the heavy SD man shot him in again in the ditch. After the shooting the clothing was loaded by the police onto the wagon and driven off. The gendarmes then left the area of the executions led by Paul and he ordered the remaining police to cover that ditch with earth. While the earth was covering the bodies I saw wounded moving and they were just buried. After covering the ditch we went home.

Pjotr Doschtschuk (Ukrainian Policeman)

Born 1924 in Grizenki. Statement Date: January 19, 1973

I lived in village of Grizenki, district of Antoniny and was a simple farmer before the war. During the German occupation around May 1942 I and my neighbor, Wassili Lyssink were enlisted by the Germans into the auxiliary police. We got uniforms with no rank emblems and wore a white armband with the German word "Schutzman". We carried Russian rifles and in command was Galitzkij, from Antoniny. The German Officer Berner led our unit. This unit consisted of 300 Ukrainian men.

In summer 1942 I was with a troop of 50 police went to Kultschiny ghetto and guarded it overnight. The next morning more police and German gendarmes arrived and the Jews were transported by wagon to Manivsti. About 10-15 wagons with Jews drove by me. I was in a human chain of police that took positions in the forest of Manivsti and on streets leading there. I know nothing of the process of executions, the participants or the number of Jews killed. I heard only the sounds of weapons from the execution site which was 800-1000 meters away. I learned that the execution in the forest of Manivsti was initiated by the SD-chief Graff from Starokonstantinov. I was part of the cordon and arrived at the execution site after the corpses were already buried.

Michail Grintshuk

(Ukrainian police commander), Born 1902 in Medwedowka. Statement Date: January 25, 1973

Q: Report on your repressive measures against the Jews during the German occupation

A: In the fall of 1941 I gave notice, on the basis of a directive by the German Commissar that the Jews of the entire Krassilov region must live in a ghetto. The notice was printed and posted in the villages; I signed it in October 1941. About 1 1/2 to 2 weeks later the deputy, a German named Freiderich, arrived in Krassilov. He led the construction of the various ghettos and resettlement of the Jewish population. Frederich himself chose the quarter of the village to be surrounded by barbed wire.

Q: When did you direct the Jews to wear identification on their clothing?

A: The order was given by the German Commissar. I don't know how this command was communicated to the Jews. Maybe I put it in the posted document.

Q. When did you order the Jews to go to the camps of Manivsti?

A: The area Commissar gave that order. In spring 1942 with the help of the local police the Jews were moved from the ghettos into the camp of Manivsti. Following that Germans and members of the police shot them. I did not take part in the executions.The

Q What made you give the order to destroy the houses in Kultschiny after the Jews were put in the camp?

A: After the Jews were put in the camp, their houses were plundered by the villagers. When I saw that, I asked the area commissar for permission to sell some of the Jewish dwellings. The commissar allowed me to sell the empty houses. A commission was formed to choose the houses. So was the decision made which house to sell. Buildings chosen by the commission I sold to villagers who wanted them. Many Jewish houses were torn down for use as building material or firewood for the German authorities.

Q: How did you estimate the value of the confiscated goods?

A: After marching the Jews into the Manivsti camp and to Orlinzy the local police took all the valuable possessions and sent them to Antoniny. Remaining goods of lesser value, with the permission of the area commissar, I sold to the local populace. There was little of value left: old furniture, pots and pans, etc., whatever the Germans didn't take. Residences were sold by me to villagers but many houses were torn down for material to build a new building. The proceeds and taxes went into the treasury of the Commissariat of Antoniny. In Kultschiny the most of the Jewish houses were destroyed and sent to Antoniny as firewood for the German authorities. I sold only a small number of houses to a few people for residences.

- - -

Yefgenia Borbitsch

I have been living in the village Orlinzy since 1922. During the time of the occupation I lived there and was working in different positions on the community property. About 800 meters away from my house was a horse stable into which many Jews from Kulchiny, Antoniny and from other places (I do not know which places) had been taken. I knew a few Jews from the village Kulchiny and from Antoniny. Now I only remember the name Lachmann who was a scrap metal collector. The Jews (about 300 people) were put into this horse's’ stable, where even the droppings had not been cleaned away. There were old people, women and children among these people.

This stable was only four houses away from my house. There was no fence around it, but was guarded by the Ukrainian police. Village residents were not allowed to approach it. Now and then a few Jews managed to flee from the stable into the village, where they were given food secretly by the village inhabitants. Two Jewish girls came to me. In their camp they were only provided with boiled beet roots. I saw myself how these beet roots were transported there. The people in the stable had to undergo insulting actions by the police. I saw myself how from 6 to 8 people were taken in groups by carriages with the material from houses that had been torn down ...”

Translations provided by Fritz Neubauer of the YIVO Institute of NYC

- - - -

Translated From Russian,Spielberg Shoah Visual Foundation, June 19, 1997

Q: What is your name?

A: My name is Klavdia Eidelmaniv.

Q: When and where were you born?

A: I was born on September 22, 1932 in the small village of Kulchiny Ukraine.

Q: How old are you now?

A: I am almost 60 years old.

Q: Tell me please about your life before the war.

A: It’s difficult for me to tell about our life before the war because I was quite little at the time war started. I wasn't even 9 years old.

Q: Tell me a little about your parents.

A: I don't remember anything about them.

What were they names?

A: My father's name was Leib Haimovich Lopushin, (The second name always refers to his father’s name.) My mother's name was Rosa Davidovna Lopushina.

Q: Did you have any siblings?

A: I had a brother, David, and two sisters, Manya and Eta.

Q: Can you describe your town, Kulchiny, before the war?

A: Kulchiny was a little town with a predominantly Jewish population. Each family owned a house.

Q: Do you remember the house you lived in?

A: I just remember that there were many rooms.

Q: Do you remember the beginning of the war?

A: In the summer of 1941 when Germans/Nazis occupied Kulchiny, all Jews were forcefully brought to one of the streets with barbed wire surrounding it. Nobody could leave.

Q: Where were your brother and sisters?

A: Also with us in the ghetto. My siblings were young at that time. The oldest was most likely 13-years old and my other sister, maybe, 11. And I was less than 9.

Q: Can you describe the place where you lived in ghetto?

A: Our family of six people was placed into a small, dark room without any beds or any other furniture. We had to sleep on the floor close to each other. It was the beginning of a new terrible life. Every morning the entire adult population was sent to work. All who were weak and sick were beaten mercilessly to force them to get up and go to work. And if somebody still couldn't get up, he or she was killed on the spot. The dead bodies were not removed for several days.

I remember there was only one water well in the entire ghetto. Lines where so long that it took several hours to get a cup of water. But things became much worse with the beginning of the winter. There was no firewood to heat the dwellings. The hunger, freezing temperatures indoor, and outdoor, no winter clothes, and the daily killings were horrible realities of our life. It has affected me terribly for the rest of my life.

I did my share of daily chores. The hardest was to get water because I had to stay in line barefoot on the snow. Finally I got very sick. I had a problem with my legs. I lost all my hair. I will never forget one episode. Little children, always hungry, often tried to get closer tothe barb wire fence hoping to get a little piece of bread, thrown sometimes over the ghetto's fence by people from outside. I remember one little girl who, among other children, rushed to the fence and picked up a very small piece of bread and immediately got shot on the spot by the policemen. All the other children started to scream and cry trying to get away. Still, to this day, I can hear the screams in my head.

Q: Where were you at this moment?

A: I was among other children by the fence hoping to get something to eat.

Can you describe the girl that got shot?

A: She was a little girl, maybe five years old, maybe less. She looked like any other child in the ghetto - barefooted, exhausted, hungry.

Did your parents have to go to work?

A: My parents were forced to go to work every day, and every day we, the children, feared that they would not come back. Jews were treated with terrible cruelty, especially at work, and especially by the local Ukrainian policemen. Jews were killed not all together but in separate groups. One day, when the men, as usual, went to work, all the women and children were taken outside of the ghetto. Everyone thought that they were also being taken to do some kind of work.

Q: Where were you at that time?

A: I was taken with all the other women and children, together with my mother and siblings. This time it was different than before. Usually when women and older children were taken to work, the little ones were left behind, but this time all children, even the youngest, were forced to go. We were taken to the woods. People realized that it wasn't the usual place of work and started to cry and scream. Mothers felt that something terrible was going to happen and they pushed their kids to run away.

Q: To where?

A: Well, it was in the forest. They should just run to survive.

Q: What time of the year was it?

A: It was in Spring..

Q: What year?

A: I think it was 1943, but I'm not sure..

Q: Who exactly drove you?

A: I'll tell everything. When children started to run away, the shooting began. Somehow I was lucky and escaped. I hid in the forest till evening and then returned to the ghetto. There was nobody in ghetto but men. My father and brother decided to make a secret hiding place for me because I couldn't live in ghetto anymore. In the attic of a deserted house, outside of the ghetto but next to it, they built a partition and hid me. Every evening my father and brother came there to spend the night with me.

Q: And what happened to your mother, brother and sisters?

A: My mother and my siblings were shot, executed.

Q: Did you see what happened to them?

A: No. I heard many shots and it was only on next day that I found out that everyone else was killed. There were rumors that the people dug a huge hole in the ground and were forced to line up in front of it and they were shot. I didn't see it. I ran away before that..

Q: Who did the shooting?

A: Germans and Ukrainian policemen. After a few days, the police made a second raid on the ghetto. At that time my father, my brother David, our neighbors, Epsteins, Gorkin (? Not clear), and Nahamovich - people who, together, had built the hiding place - hid together in it. I remember screams and shots during the second raid. It was terrible. They searched our attic but didn't find us. It was a miracle. We spent three days in our hiding place without food or water. It was obvious that without food and water we wouldn't survive much longer. Then my father told me to leave and go to a nearby villages and beg for food. He told me, if somebody asks, to say that my name is Marina Krevitsky..

Q: Why did he tell you to change the name?

A: Because he knew that if I tell my real name Haika everyone would know that I'm a Jew. He repeated many times what I had to say if somebody would ask me - that I'm not a Jew but a Ukrainian. I was terribly thin, without hair and limping. They gave me a bag and I went from one village to another begging for food. It took me all day and at night I came back to our hiding place..

Q: How did people in the villages treat you?

A: People were kind to me. They were hungry themselves but still shared bits and pieces of their food with me.

Q: Did they ask you anything?

A: No. I pretended that I was mute and couldn't speak. By the night I returned back and brought food and water but it was only enough for a few days. Then our neighbors decided that it was time for us to leave our hiding place and, in the middle of the night, they left and I left with them. They went their own way and I went to the villages to beg for food again for my father and brother who still stayed in the hiding place. Much later, I found out that our neighbors had joined the partisans and survived the war. They still live in Belarus.

During my wandering from village to village I knocked on the door of one of the houses in the village of Zelyonoe (Translated as Green.) A woman opened the door. She was very kind to me, gave me some food and, at the end, asked if I'd want to stay with her and help with her small children. I didn't say anything and left. After two days of traveling, I returned back to our hiding place but my father and brother were gone. Later I found out that neighbors spotted them and reported them to police. I went back to Zelyonoe and spent the night sleeping by the side of the road. In the morning, I went back to the woman who had offered to let me stay with her. She took me in and I helped take care of her baby.

Q: Do you remember the names of this people?

A: Her name was Maria and her little boy's name was Sergay. I don't remember their last name. The village of Zelyonoe was in the middle of the forest and the Germans didn't visit it very often. Idon't know if the woman guessed who I really was but she didn't tell the Germans about me. I helped her with everything around the house and with the baby and I stayed with her until Ukraine was liberated. By that time of all my family, only my aunt and uncle were alive. He was my father’s brother.

Q: When did you find out that the war ended?

A: When the war ended, I didn't know about it. I didn't even guess that the war was over. After the war, my uncle tried to find out if anybody from our Lapushin family survived. He wrote letters to different people and organizations asking for any information about the family. The only answer he received was that entire large family perished. Finally somebody answered that “in Zelyonoe village, there lives a girl, a small very sick girl, with the last name of Lapushina. If you want, check her out”. During the war my uncle with his wife were evacuated. Later my grandfather came to visit and decided to stay with them. When they received the letter about the girl, my aunt and grandfather decided to go to Zelyonoe to look at the her.

When they walked into the house where I lived, I didn't recognize them and thought that I was betrayed and that strangers had come to take me to some German soldiers to be shot. They asked me my name but I was so scared that I didn't tell them my real last name. And when they asked me if I was Jewish, I answered: "No. I'm Ukrainian". My aunt noticed that I was shaking and scared and she took me into the other room, just she and I, and she begged me to tell her my real name. But I kept telling her: “My name is Maria Krevitskaya”. Than my aunt asked me if I knew anybody from the Lapushin family. She told me it's important because Lev Lapushin is alive. I started to cry. Then I told her what happened to me, and she took me back with them. My uncle and aunt were very good people.

They took me to be examined by the doctors. I was so sick that the doctors didn't believe I could survive. My aunt didn't give up and decided that the only surviving member of the family must live. She and her husband did everything so I would get well. They took me to the city of Kiev and Dneipropetrovsk to see different doctors, specialists. It took me several years to recover. My uncle and aunt used to live in the [Eastern] city of Chelyabinsk which was never under German occupation. That's why they survived. My grandfather lived in Kulchiny, but he tused to visit my uncle before the war started. During the war he stayed with them in Chelyabinsk. So, he also survived. My aunt and uncle have two children: my cousin Fima and my cousin Sofia. They became my dear brother and sister. I had several surgeries. One on my knee, one my shoulder, and others. I became totally disabled. Now I have my own studio apartment not too far from my daughter. She comes often to visit and helps me.

Q: Did you tell your daughter about what you went through during the war?

A: Yes. She knows everything.

Q: When did you tell your daughter about that?

A: I told her a while back when we still lived in the Soviet Union. [She was now living in Isael.] I told her that you should be proud to be a Jew and what happened to me shouldn't happen to anybody ever again. My granddaughter even told my life story at her school. My older daughter received a prize for the best writing composition in which she described my life during the war.

Q: After the war did you see anybod you knew during the war?A: No.

Q: Do you go to synagogue after the war?

A: Yes our family goes to synagogue. My older granddaughter studies theHebrew language in college and every Friday she visits a synagogue. She is very religious. The little one goes to the Hebrew Sunday School. You should see how we all celebrated Passover this year. They led the first Seder and later performed a play about this holiday. I couldn’t watch it without crying.

Q:Did you celebrate Jewish holidays in the Soviet Union after the war?

A:Yes. My uncle and aunt were religious and we always celebrated the Jewish holidays together at their place. We couldn't celebrate at our place. My husband and I could have lost our jobs and our daughter would have been expelled from college if the authorities found out. No. We couldn't do it in our place. it was prohibited.

ARKARDY WEINER

I, Weiner Arkady Petrovich, was born on April 22, 1927 in the village of Manivtsi, Krasilovsky District, Khmelnitsky Region.

There were seven of us: father, mother, three sisters, brother and I. Before the war, we lived in a village. Mother worked as the head of the poultry farm. My father was at different jobs. The war began, and after the Hitlerites occupied the Manivtsi on July 7–8, 1941, we were all resettled in Kulchin, in the ghetto.

Jews from three districts were driven into this place, which was fenced with wire. Everyone was hung up with such yellow circles, front and back, with a blue edged star of David. Inside the ghetto were Jewish, and outside - Ukrainian policemen. An indemnity was imposed on us: everyone had to hand over gold, jewelry, who had what. If you didn’t bring it, it means under execution. Forced to give money or valuables.

In May 1942, in the rain, through the mud, all the young were driven, like a herd, from Kulchin to the village of Orlintsy in the Antoninsky district (8 kilometers). There we were settled in stables, cowsheds, pigsties - in the collective farm complex. They gave me feed beets, sometimes pea soup.

We were sent for hard work: we loaded large stones onto tall German carts. If the stone could not be loaded, it was necessary to manually push 5-6 kilometers to the appointed place - to the premises in the Potocki park. There they unloaded this stone, half an hour break, again loading and manually pushing the cart back.

We were led all this distance for show, so that the locals could see what the Jews were. And if we could not load the stone, it fell and nailed all who loaded. Then the next group was taken, and those who were nailed to the same cart were abandoned.

This went on for two or three months. Then they announced that they would send us from the Antoninsky railway station. And we were brought to Manivtsi, that is, to my native village. Before the war, there was a military utility in large two-story buildings. From there we were driven to repair the Starokonstantinov-Teofipopop road. We were not given any tools. With our hands we pulled out weeds along this road. So we worked for ten days.

Then they took away men, eighty people, the healthiest and strongest, gave them bread, gave them shovels and said that they were sent to a sugar factory four kilometers away, to peat. They were gone for two weeks. After exhausting work on carrying the stone and on the construction of the road, the family was transported to a concentration camp located between the villages of Manivtsi and Rosolivtsi. Jews from the Krasilovsky ghetto created in the spring of 1942, as well as from neighboring villages, were also driven here.

In July 1942, 8 or 10 cars with high sides drove up to us - in such silos were usually brought for livestock, so as not to crumble. The loading of Jews began, and mass execution began. All buildings were surrounded by Ukrainians, policemen and Germans. Neither food nor water was given. Among us were small children, there was crying, screaming, everyone was hungry. I opened a small window from the second floor and wanted to jump on the German guard on his head. But they pulled me away, and he began to shoot. All around said: what God has given, it will be so. Children were given urine .... Everyone realized that imminent death was approaching.

My mother and two sisters were in the first building, they were already taken away ... I was with my younger 13-year-old brother and third sister, 19 years old. The groups were periodically driven into a truck and taken away for execution.

And our turn came. The three of us drove in the same car. The car was crowded with people, and whoever fell underneath was crushed. The sister began to resist when they drove us: they hit her on the back, nailed her spine and threw her into a car. I decided that I would not go into the pit, let me be better killed on the go, but I will try to escape. Near me in the corner of the body stood a policeman. I got up and threw him overboard. He fell to the ground, and I jumped after him and started to run away. They started shooting at me and wounded me. I jumped into the reeds by the lake, and the policeman did not see where I was. So I stayed alive.

The poet Kolomiytsev wrote a poem about this tragic day :

Pіd Manivtsiam at 42nd, at 42nd they asked to have mercy on God,

At 42nd, at 42nd, mowed, mowed, mowed.

At the 42nd Stylka we fell into thin air, if the machine guns were mowed down,It’s already hushed up, it has become hushed up at all one grave.

Skilki shoved us there shovels in terrible bagatogolossі.That polity, porahuvati can not be better.

Pіd Manіvtsyami stumbled dolі, if kulemeti mowed.Pіd Manіvtsyami calmed down at the polі three brotherly graves.

Three mass graves ... For five thousand people ... They shot in three stages.

... I managed to hide in the reeds, and I was no longer sought. I came to the director of the school where I studied before the war. He hid me in the barn where the cow stood because he was afraid that his housekeeper would give me away. I spent the night in a barn, under a manger, sucked milk at a cow, lived like a driven animal. The director gave me a certificate that I am from a boarding school and my name is Muzychuk Pavlo Ivanovich. And I went to work on a state farm - an industrial enterprise created by the Germans during the occupation.

In 1944, the Red Army came, and I went back to my village. And in the same year, I, a minor, went to the Red Army, at the age of 17, and stayed there until 1951.

In 1948 he met his future wife Lida Iosifovna, we got married. We have been together for over 60 years.

After the army, I graduated from evening school, then a cooperative technical school, and then an institute in Lviv.

And the brother, sister and other Jews with whom I was driving in the same car were shot. No one survived, no one was saved that day, except for me and another woman, a teacher from Starokonstantinov Faina Grubber. She managed to escape: the machine gun burst did not hit her, but she fell into the pit, and was littered with the bodies of the dead. At night she climbed out of this pit.

She left for Israel and, unfortunately, has already died. In 1998, she wrote me a letter, which I want to give here:

“I have received your letter. You can’t read without pain. Pain ... The shadow keeps me on the ground, not underground. This wound will go away with me. Thank you for responding, although it's too late. But better late than never. Dear my brother in misfortune! All the time I am grateful to the Almighty that I left one sacrifice so that there would be someone to tell about our torment. I'm glad that I’m not alone. I myself come from Kuzmin. Survived the Krasilovsky ghetto. Eight times was on death row. Finally, she herself fell into the pit. The bullet passed. I don’t remember how I got out and how I could get from there to Kuzmin, where there was a salvage shed. My life is history, and man risked salvation for me. I am connected with the light - Israel, Moscow, USA, Latvia, Kiev, etc. My salaries and pensions go to correspondence. During the ceremony, a diploma and medals were handed to the rescuers, the Righteous of the World, in the embassy of Israel in Kiev. I had a meeting with my living saviors, children and grandchildren who passed away. She spoke from the rostrum twice. Showed on TV. I have two certificates: “Ghetto Prisoner” and “Partisan Ticket”. The book of saviors, author Koval from Latvia, a book in two volumes, with his own memories: photos of saviors, many victims of fascism, my portrait in the Starokonstantinovsky museum. The letter does not describe everything. If you can, come, please, get closer. I am born in 1918. My finals are on the doorstep. The war took everything ... Here is a brief about yourself. Waiting for your letter. Report on arrival. All the best to you. I have two certificates: “Ghetto Prisoner” and “Partisan Ticket”. The book of saviors, author Koval from Latvia, a book in two volumes, with his own memories: photos of saviors, many victims of fascism, my portrait in the Starokonstantinovsky museum. The letter does not describe everything. If you can, come, please, get closer. I am born in 1918. My finals are on the doorstep. The war took everything ... Here is a brief about yourself. Waiting for your letter. Report on arrival. All the best to you. I have two certificates: “Ghetto Prisoner” and “Partisan Ticket”. The book of saviors, author Koval from Latvia, a book in two volumes, with his own memories: photos of saviors, many victims of fascism, my portrait in the Starokonstantinovsky museum. The letter does not describe everything. If you can, come, please, get closer. I am born in 1918. My finals are on the doorstep. The war took everything ... Here is a brief about yourself. Waiting for your letter. Report on arrival. All the best to you. Report on arrival. All the best to you. Report on arrival. All the best to you.

Sincerely, Faina Grubber-Savchuk.

I am sending a poem to your address. The Strata, Petro Savchuk .

Gruber Faunichi, who took part in it, took pensioners from the city of Starokostyantinov, miraculously, there was a miraculous appearance in the death hour of the mass separation of the Germans from the Occupants.

The nerves were rooted and lived, the black choke to fall asleep.

When you went to the grave, the Lord himself bowed your hand at you.

People fell, drenched in blood, like a machine gun from a shoulder.

Wee fell as well, as if it were killed, ale in soul lost a soul.

Chi to the army, chi before the glory of God, at their own heat they knew.

Among the corpses from the grave were seen, I, mov the ghost, fearlessly sent.Yoshli nightly, twisted, goals *,

They were making their way, they didn’t know who you were going to die, and if you were going to die.

"Get out!" - one little thought. Well, thank you, people are kind, sheltered and given a lie.

That boule riziki noble. You should remember about them.

And you live, come to the humpback,

Together with the maple, in order to stick the old man.Thank God that you are not among them.

Here is my story. This is the thousandth, milligram share of what happened during the war. Where the Germans were, everything was wiped off the face of the earth. Where the Romanians were, part of the people left alive - hundreds, thousands.

We need to know and always remember what fascism is. Until the end of our days, our duty is to defend our interests, to remember these people, and not to forget what happened. He who does not remember the past cannot know the present and the future. Therefore, all living things, no matter who they are, whatever nationality that person is, pain must remain in his soul for life. If he feels it, understands and teaches others and his children - this is a person. And if he does not know this, does not remember and does not want to remember - this is not a person. All that people can do good, they thereby make a monument for themselves. Everyone will remember them. And I believe that wherever, on whatever land a person is buried, his grave is worthy of a noble attitude towards it. Unfortunately, we do not see this now in relation, for example, to those three mass graves. After the war, people built a monument at their own expense. But everything has already fallen into disrepair, it is necessary to paint again, to make a new fence.

Worst of all, these graves were dug up and robbed! Even two years ago. After all, people know that many of those killed had gold, the dead had golden teeth. And here they come, they do “excavations” in order to get these golden teeth out of the skull.

About 30 years ago, in the village of Vitievka, they began to dig a pit for the construction of some kind of structure. And just dug in the place where the mass grave turned out. And the excavator dragged these bones, skulls, gold shone, and everyone rushed to these bones, pulled out ...

We appealed to the authorities of the Khmelnitsky region with a request to support these graves, but, unfortunately, no one is doing anything. Local authorities do nothing, all hope for international sponsors.

* Bo before Tim, as if they were breaking up - they spread out, took away all the clothes, burned, took away, maybe gold was blown into someone.

Fragment from the book of Boris Zabarko “We wanted to live ...”, Articles 126-131.

- - - -

Yahad-in UnumAarl

from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Yahad-in Unum was a Ukrainian-Jewish man born in 1927 discusses events in Manivtsy (Manivtsi), Orlintsy (Orlyntsi) and Kul’chiny (Kul'chyny), Khmel'nits'ka Oblast: arrival of German forces in Manivtsy (Manivtsi) and their welcome by some Ukrainians; establishment of a ghetto in Kul’chiny (Kul'chyny) for Jews from Manivtsy (Manivtsi) and other towns; details on ghetto life and on Jewish and Ukrainian police; transportation of able-bodied males, including witness, to Orlintsy (Orlyntsi) for two months of exhausting work; preparation for shooting of Jews; digging of a trench by some 120 men; loading of Jews, including witness, his mother and four siblings, into trucks for transportation to the shooting site; escape of witness from a moving truck and escape from his pursuers; failed attempt of witness' brother to run from the trench area; survival of one woman who climbed unhurt from the trench; assistance to witness from Ukrainian school principal who gave him Ukrainian identity papers; work by witness on a state farm as a driver; meeting between witness and his father, an inmate of the nearby Starokonstantinov (Starokostyantiniv) ghetto; later destruction of ghetto and killing of Jews, including his father; and the names of witness, his parents and siblings.

* * *

This Notary was located on the bottom of each witness statement

This Protocol was read aloud at my request by the under research leader. I testify it was transcribed correctly.

The deposition was led by

the head researcher of the KGB at the council of ministers of the

Ukrainian SSR in district of Chelmnitzkij.

Counselor: Lieut. Ttkatschuk and

signed: Tomtschuk.

The correctness of the copy of the minutes is affirmed: Asst. of the State Administration in the district of Chmelnitzkij.

Counselor: signature (?Sarubin) illegible. May 30, 1973

I notarize the correctness of the above translation. signed:

Waldemar Awakowicz.

Stamp of notary for correctness of the copy.

Dortmund, Oct. 3, 1973

ADDITIONAL KULCHINY HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY

To view the following slide shows,click on USC Shoah Foundation site ane login as User: myKulchiny using the password 0Kulchiny0 (Where 0 = zero). Once you have logged in, click on a name vto view the show.

* * *

Holocaust Victims from Kulchiny and Surrounding Area

Translated By Edward Berkovsky

|

A poem by a resident of current Kulchiny provided by Dmytro Severniuk

Shortly there the shot roared on the hill

Guard has shot a man again.

There Ghingold, the accountant of our collective farm fell,

Measure of his life was shortened.His wife ran to him screaming

To hug, to say goodbye, but

Her and their son Milya,

The solder ruthlessly shot too.

Praying without grumbling went Semites,

And shots were heard again and again.

Young and old died there, and children flowed and mixed with dust.The entire road from Kulchiny to Antonina

flooded with their blood

And only God can judge the sin

Оf foolish, reckless loss of life.

With this burden of human tragedy,

The memory of which has boiled in my soul

I didn't find the peace of mind,

Painful aching is tickling my heart.

it wasn't easier because

Germans were beaten on all fronts,

were chased from foreign lands before

Only bitter smile on the lips from this.

Apparently, because I was a green young man.

I saw a rise in fatal folly

And the inevitable course of self-defeat

Will cause Germany's defeat in the end.

One must be really mad,

aim a blow at the human race.

To engage in arbitrary genocide

To cherish only Aryan lineage.

I was hurt with the wounds of Ukraine

Kulchiny were aching in my heart,

Because I can't forget as Jews were led to Antoniny

They were coming in silence.

Men, women, old and young -

The column of five hundred or more

They went to meet their fate,

Guards drove them to go faster.

Convoy is slowly moving up the hill -

I stood near the Brovarsky gate.

An old Jew was saying something to the guard,

Keeping hands on his stomach.

Perhaps, that he can't walk.

Just a shot was heard in response,

Old man swung and fell to the wayside,

He glanced toward the convoy and died.

* * *

KULCHINY GHETTO AND MURDER

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, pp. 315-16, statement of Mikhail I. Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973. Graf died in 1953.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Concluding Report, March 18, 1971, and Instruction (Verfügung), June 18, 1974. Schorer perished in 1943 and Paul died in 1969.

Ibid., Vol.I, pp. 368-74, statement of Pyotr Tomchuk, December 18, 1972. Tomchuk dates the establishment of the ghetto in the summer of 1942.

GARF, 7021-64-793, pp. 95, 98.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 209, statement of Yakov Y. Kondratiuk, December 19, 1972, and p.217, statement of Domna Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 217, statement of Domna Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973.GARF, 7021-64-793, p. 95.

Ibid.; BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, pp. 344-49, statement of Denis Paska (resident of Manivtsi), March 14, 1973.

Vol. I, pp. 256-61, statement of Pyotr A. Doshchuk, January 19, 1973 (former local policeman in Gebiet Antoniny);

pp. 287-99, statement of VasilyS. Lysink, February 1, 1973 (former local policeman from Antoniny).

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 214, statement of Nikolay S. Kravchuk, March 15, 1973.

bid., Concluding Report, March 18, 1971, and Instruction, June 18, 1974; Vol. I, pp. 256-61, statement of Pyotr A. Doshchuk, January 19, 1973. Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 344-49, statement of Denis Paska (resident of Manivtsi), March 14, 1973.Ibid., pp. 199-203, statement of Mikhail A. Grinchuk in his own case, March 30, 1947.

VHASH, # 30173, testimony.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, pp. 315-16, statement of Mikhail I. Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973. Graf died in 1953.

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Concluding Report, March 18, 1971, and Instruction (Verfügung), June 18, 1974. Schorer perished in 1943 and Paul died in 1969.

Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 368-74, statement of Pyotr Tomchuk, December 18, 1972. Tomchuk dates the establishment of the ghetto in the summer of 1942.

GARF, 7021-64-793, pp. 95, 98; BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 209, statement of Yakov Y.Kondratiuk, December 19, 1972; and p. 217, statement of Domna Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973.BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 217, statement of Domna Moskaliuk, March 21, 1973.

GARF, 7021-64-793, p. 95.

Ibid.; BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, pp. 344-49, statement of Denis Paska (resident of Manivtsi), March14, 1973.

Vol. I, pp. 256-61, statement of Pyotr A. Doshchuk, January 19, 1973 (former local policeman in Gebiet Antoniny).

pp. 287-99, statement of Vasily S. Lysink, February 1, 1973 (former local policeman from Antoniny).

BA-L, ZStL, II 204 AR-Z 442/67, Vol. I, p. 214, statment of Nikolay S. Kravchuk, March 15, 1973.

Ibid., Concluding Report, March 18, 1971, and Instruction, June 18, 1974; Vol.I, pp.256-61, statement of Pyotr A.

Doshchuk, January 19, 1973.

Ibid., Vol. I, pp. 344-49, statement of Denis Paska (resident of Manivtsi), March 14, 1973.

Ibid., pp. 199-203, statement of Mikhail A. Grinchuk in his own case, March 30, 1947.

VHASH, # 30173, testimony of Sima Slutzki, June 25, 1997.

© 2012 David Winer