OUR KULCHINY ANCESTORS

CONTENTS

CLICK ON ITEM TO DISPLAY

Pincus (Benjamin) Winer by Grandson David J. Winer

Impressions of Kulchiny by Herb Bixhorn

An Immigrant Story by Jerome L. Blafer

Kul'chiny Guests, by Dymitro Serverniuk

This section is dedicated to the brave Kulchiners who emigrated from their homeland in Kulchiny and the surrounding communities to strike out to new worlds where they could make a wonderful life for themselves and their descendants.

We know of no 20th century Kulchiny-born immigrants who are alive in 2012. But the stories about those brave people and how they came to the US can live on for many years for their descendants who are yet to come. We encourage all who remember a Kulchiner to write or record their memories so that they may be included in this section of the Kulchiny Kehila site. Do you have a story about a Kulchiner or about old Kulchiny? Contact David Wiener at DwinerLaw@aol.com.

By Grandson David J. Winer

Although I knew almost nothing about my grandfather Pinkas Weiner (who’s name in America became Benjamin Winer, and was known as Ben,) he always intrigued me. In 1968, when I was 7 years-old, he died in Rochester, New York at the age of 78. The only images that remain of him are a couple minutes of grainy video and a few photos. No one, not even his own children, knew the name of his parents nor the name of his shtetl in Ukraine. Aside from a sister, who emigrated to the US, no one knew if he had any other siblings or relatives. He was never asked and he never spoke about it.

Part of the mystery was solved in 1995 when, while by rummaging through my uncle Ron Winer's attic in Rochester, NY, I found a money order for $19.00, dated 1918, sent to "Chaim Herschel Weiner in Kolczyn” (the Polish spelling of Kuchiny). A subsequent research of immigration records confirmed that Ben was from the small village of Kolczyn (now called Kulchiny). But an internet and library search revealed no written information about this village. My interest was piqued and I decided that the only way to learn about my grandfather was to visit this village, which I did in July 2011.

In 1910 at the age of 20, Benjamin Winer took a solo trek across the expanse of Russia and Europe to the embarkation port of Hamburg Germany. It was a time before the Russian Revolution, when the Jews of rural Ukraine lived in poverty and with the constant fear of Pogroms. He left his entire family behind and was never to hear from them again. One can only imagine the anxiety he had upon arriving at Ellis Island, a land of strange customs, an unknown language and a people he knew nothing about. He left the ship with only his determination. That and $20.00.

But, with hard work, the American dream embraced Benjamin Winer and he embraced it back. He eventually owned his own home and had the honor to watch his eldest son graduate from college, a first in his family (Harold Winer later on became an attorney, as did his sons, David and Evan. In fact all Ben’s grandchildren were graduated from college and many have advanced degrees). After an arduous life in New York as a tailor and factory foreman, he died in 1968, at the age of 78, leaving behind a wife and four children.

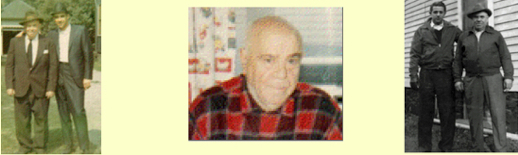

Photos: Left - Harold and son Ronald, 1966; Center - Benjamin, 1965; Right - Son Harold with Benjamin, 1946

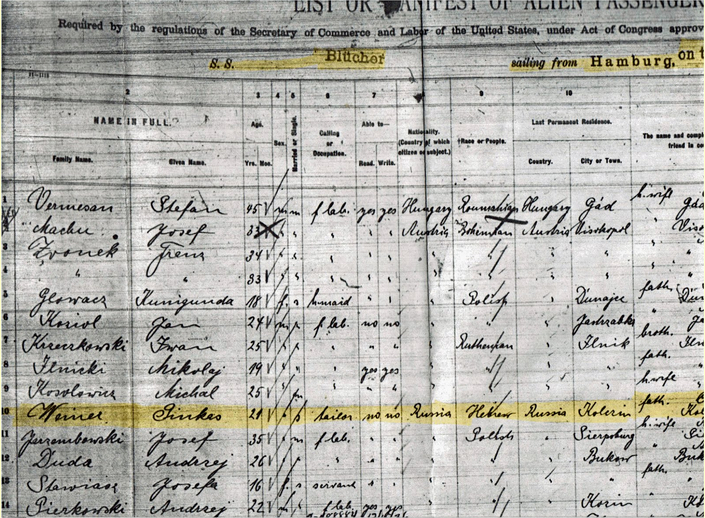

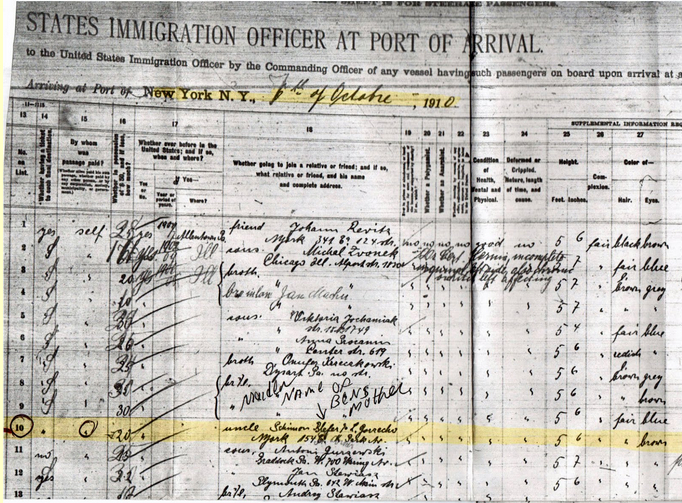

Ben Winer was born in Kulchiny to Chaim Herschel Winer and Rachel (Roza) Blafer. He left for the United States on September 24, 1910 aboard the “SS Blucher” which departed from Hamburg Germany (the German vessel was later sunk by the British in WWI.). According to the ship’s manifest “Pinkas Weiner” was 21 years old, was unable to read or write any language, was 5’6’’ tall, a tailor, and had $20.00 on him. He arrived at Ellis Island on October 7, 1910 and initially went to New York City to the home of Shimon Blafer, a relative of Ben’s mother. From there he went to upstate New York where a cousin had a junkyard business in the town of Perry. He later took a job with Levy-Adler Clothing in Rochester NY, starting as a clothes presser. Hard working and fair to others, Ben was promoted to head foreman and worked there until he retired.

Ben was also resourceful and entrepreneurial, buying old homes and apartment buiidngs from estates and foreclosure sales. He would then buy the fixtures and other materials needed to fix up these home from junkyards and estates. Ben was known as very clever and was a tireless and diligent worker who never complained. He did everything to provide for his family, giving them a decent home and food on the table. He was very good to his tenants and was hesitant to evict people for lack of payment. He was known to give tenants several chances before he took any action.

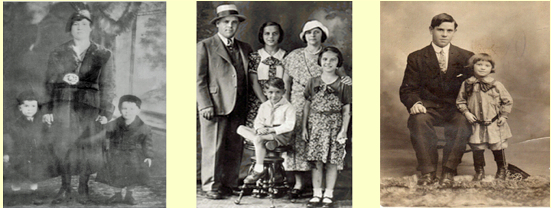

Photos: Left - Rebecca Winer, sons Phil and Haskel 1918; Center - Winer Family - Benjamin, Anna, Harriet, Rebbeca and Harold 1933; Right - Benjamin 1913

Ben, his wife Anna (née Lambert) and their children - Harriet, Becky, Harold, and Ronnie - lived on Clifford Avenue in Rochester. Ben’s sister, Rebecca (Ruchel) Sarver, arrived in the US in 1912 and eventually lived, with her family, in a house owned by Ben, that was right behind his. Ben spent a great deal of time with the Sarvers, who as immigrants themselves, shared a common language and culture. That changed when his sister Rebecca died suddenly, following minor goiter surgery at the age of 27, on January 2, 1921 (she had choked to death while recovering in the hospital). Rebecca’s children, Haskell and Phil, remember Ben Winer as being very generous and kind to them when they were children and he would eat over at his house often. They recalled Ben being completely devastated by his sister’s death. Ben never forgave her husband, Joseph, for not being in her hospital room when she died.

It is unknown whether Benjamin had any other siblings or relatives in Kulchiny. In fact, the fate of his parents or any other relatives is unknown. There is no correspondence, letters, photos, or any documentation of his family. All that remains is a page from a “Memorial Book” from Ukraine which lists a “Rosa Weiner” from Kulchiny as being shot in the Manvisti forest by the Germans in 1942. It was likely his mother, as the name is the same.

Because of Ben Winer’s brave decision to leave Kulchiny, twenty-four people have been born who call America home. Among his decendants are doctors, lawyers, accountants, teachers, and even a Harvard University graduate. Were he alive to see what he left behind, I am sure the Pinkas Weiner, from a shtelt called Kulchiny, would be very proud. We are certainly proud of him.

Children |

Great Grandchildren |

||

Harriet Winer (Cohen) Rebecca Winer (Treister) Harold Winer Ron Winer |

Benor Winer Ariel Winer Abraham Winer Bennie Winer Anna Winer Bradley Stein Jordan Stein |

Allison Stein Matthew Cohen Maxwell Cohen Samantha Cohen Daniel Treister Allison Treister

|

|

Grandchildren |

|||

David Winer Evan Winer Todd Winer Beth Winer |

Michael Cohen Nan Cohen Jeffrey Treister

|

||

BENJAMIN WINER TIME LINE

Birth Dates used: April 1, 1892 on Social Security application, July 2, 1887 on WWI draft registration card, May 15, 1891 on Petition for Naturalization.

September 25, 1910, Left Hamburg, Germany on the ship Blucher to NYC.

October 7, 1910 arrived at Ellis Island and went to the home of Shimon Blafer in NYC

November 30, 1912: Sister Rebecca (Ruchel) arrives from Kulchiny.

March 13, 1913, received his certificate for English classes.

1915 Money order to Russia to his father Chaim Hershel Weiner.

Money orders in 9/1/28 to Joseph Schnaiderman for $25.00, and 11/12/13 and 2/17/26 to Israel Rimer in the village of Nikolieyev for $10.00 & 15.00. These people are unknown.

June 5, 1917, completed draft card for WWI (worked for Levy-Adler clothing).

May 26, 1919, applied for U.S citizenship.

January 2, 1921: Sister Rebecca dies age 27, leaving two small boys, Phillip and Haskell age 5 & 6.

January 29, 1924, received his Certificate for Naturalization.

December 1, 1936, applied for Social Security as employee of Levy-Adler clothing.

October 13, 1919, married Anna Lambert.

Children Born: Harriet in 1919, Rebecca 1921, Harold 1926, Ron 1935.

1968 Died in Rochester NY.

Benjamin’s Ship Manifest on US entry at Ellis Island

Page 1

Page 2

* * *

By Herb Bixhorn of Virginia During a Visit to Kulchiny

September 20, 2005

My father, Saul (Sholem) Bixhorn was born in Kulchiny in 1910 and came to the U.S. in 1921. He was a great story-teller, and although he was only 11 when he left Kulchiny, he was full of stories of his youth there. Following are the facts I know about my family’s background in Russia (they never referred to it as the Ukraine).

The family name in Kulchiny was Bixgorn. My father, his three brothers and sister lived in one house with their parents and a childless aunt and uncle. Kulchiny had four streets: Shiel Goss (synagogue street /lane), Markh (market) Goss, Shpatzier (strolling) Goss, and Yene (the other) Goss. A river ran through the shtetl and widened into a pond because of a dam with a waterwheel.

My grandfather left his family in Russia in 1911 to earn money in America to pay a debt he owed in Kulchiny. We have a letter in Russian from a village “elder” who apparently was serving as an intermediary to the creditor, thanking my grandfather for his payments. My grandfather intended to return to Russia, but World War I and then the revolution intervened. In the meantime my grandmother died of cholera or typhus. (My grandmother’s maiden name was Shrago and she came from the nearby shtetl of Krasilov).

So in 1921 my grandfather sent for his children to come live with him in East St. Louis, Illinois. This and St. Louis, Missouri is where the family was centered in America. The family’s passports were issued in Poland since that area of the Ukraine fell under Polish control for a brief period in 1921 during the chaos of the revolution and ensuing civil war. My father’s uncle and aunt decided not to come and remained in Kulchiny.

Following are some anecdotes I remember from my father:

My father’s family made moonshine vodka in a hidden area behind one of their bedrooms. But there was a chimney or some other outlet for the smoke of the distilling process to leave the house. Police/tax collectors used to come snooping to find where the smoke was coming

from. The area was known for having a lot of illegal vodka-making. My father said his family

would put someone in a bed next to the hidden door. They would tell the revenuers they could search if they wanted to, but not to disturb the person in the bedroom who had typhus. This would end the search.

During the spring thaw, the roads were a morass of mud and remaining snow with armies trying to get their horses and wagons through. One day my father watched as exhausted soldiers were trying to pry wagons out of the mud. One soldier walked to the side of the road and sat down. An officer road up on a horse and told him to get back to work. The soldier refused and

continued to sit there. The officer pulled out a pistol and pointed it at the soldier’s head. The soldier cried out “My G-d” as he was shot dead.

Russian soldiers were sometimes quartered in their home when an army was passing through. The family would spend sleepless nights, but was never harmed. When they heard the sound of gunfire, the family would do one of two things: either run to the forest and hide until things quieted down, or run to their attic where they would lie on pillows and quilts piled high on the flooring to stop any bullets. My father says that on these occasions they would hear people coming through their house and firing their guns.

In reading these anecdotes, remember that my father was a child and didn’t know whether the armies he saw were fighting World War I or were Whites and Reds fighting in the revolution/civil war. He told me that he thought that some of the “armies” such as those they hid from in their attic were simply gangs of bandits taking advantage of the chaos of the times. I thought some of these stories might be a bit contrived, but a Russian woman (not Jewish) who was from that area told me that these stories rang true, especially the ones about illegal vodka.

During the 1930’s my father’s family in St. Louis corresponded with the aunt and uncle who remained in Kulchiny. The letters ended with the German invasion of the Soviet Union. In 1948 my father and his brothers received two letters from the aunt and uncle who had remained in the Soviet Union and now lived in Baku, Azerbaijan. The aunt and uncle had somehow escaped the Germans in Kulchiny and made their way to Azerbaijan. The letter gave no details; it simply stated that what had happened to them during the war could not be described, and that our beautiful family no longer existed. She asked for the family in America to send letters and packages to help her in her extreme poverty. Our family sent these, but she never received them. Her last letter was poignant and bitter. She thought that we had abandoned her. Clearly the Soviet government had not allowed our letters or packages to reach her, but for some reason had let her letters reach us.

* * *

Morris Blafer - An American Success Story

by Jerome Blafer November 29, 2011

During the years 1895 to 1917, some Blafer family members, including my father' brother Sam emigrated from Russia to the United States. They sent back stories about that wonderful country. In 1917, amidst the turmoil and confiscations of the Russian Revolution, my father's father decided it was time for his 15 year old son, Morris Blafer, my father, to go to America. He took him to the Russian border and sneaked him across. My father made his way to Warsaw. He never spoke to me about how he got there, who he stayed with, or how he sustained himself.

Meanwhile, brother Sam worked on getting permission for Morris to enter the US. At that time, only mothers, father, or children were permitted entry; siblings could not be sponsored. So, Morris waited in Warsaw. And waited... And waited. No word came from Sam about immigration.

Morris became homesick after a couple of years of waiting. He made his way back to the border, crossed over to Russia, and went home, where he surprised his family. It did not take long for the Communists to learn of his return. They went to his home and arrested him, taking him to the local jail. That night, my grandfather went to the jail and bribed the jailor to release my father. He took him to an unguarded place on the border. He kissed him. "I love you." he said. "Don't come back."

Once again, Morris went to Warsaw and waited. Ultimately, a letter came from Sam telling him to get passage to Ellis Island, New York. Sam's Congressman, in New Jersey, had added a paragraph giving permission for Morris to enter the US to a bill that was passed by Congress.

In 1922, Morris stepped off the ship at Ellis Island and was cleared for entry. He expected to be met by his brother, but Sam was nowhere to be found. After waiting a while, he left and made his way to New Jersey, with no idea where that was, with hardly any money in his pocket, and not speaking English. What a surprise for them when his nieces opened the door to see this "tall, handsome stranger standing in the doorway wearing a white suit and a straw hat and holding a walking stick. Later Sam returned home. He had arrived late at the ship and the passengers were all gone.

Morris slept at his brother's house that night. In the morning, he awoke and headed to New York City. He quickly found a job in a grocery store that included meals and lodging. He worked the rest of the morning until his boss told him to go upstairs where his wife would prepare a lunch. Upstairs, the wife was finishing changing a smelly, soiled diaper on her child. She put the baby down and started to cut up food to prepare the meal, not having cleaned her hands. Morris got up and left. He went downstairs, told the boss he quit, and left.

That afternoon, he found another job, one that also offered food and lodging. This job was a good one. Morris was a hard worker. Like most 'green horns', he lived on little and sent much back to his family in Europe. They had been well off before the revolution but now were poor. Morris managed to save money. While working at the store, he sold insurance and punch cards and referred people to a clothier who gave him a commission. He also earned a little money as the Secretary for the Kulchiner Society.

Morris’ new boss dabbled in real estate. One day, he came to my dad and said he needed money for a deposit at a bank so he could buy an apartment house. My dad helped him and became part owner of a building. When the depression hit, he went to the the banks who were repossessing building because the landlords could not pay for the mortgage. My father made deals with the bank who turned over building to him on the promise that he would make payments on the mortgage.

Doing most of the labor himself and hiring workmen to do what he could not, my father repaired the building and rented the apartments. He made good on his promise of payments to the bank, bought additional properties, and he slowly prospered. Times were not good; the depression was in full swing. When renters could not keep up their rent, my father would tell them to pay him what they could and catch up when they were able. He never evicted a single tenant. And he was rewarded in his confidence in people since almost every single one of his in-arrears tenants eventually paid.

My father's story is a true American success story. From scratch, with no money, speaking little English, and through his intelligence, hard work, and persistence he made it good in America. Eventually, he married and he and my mother raised three children who, themselves, were successful in America.

Yesterday, my wife and I returned from the Bat Mitzvah of my great-niece. My father would have been proud to see his descendants - 3 children, 9 grandchildren, and 17 great-grandchildren.

by Dymtro Severniuk June 20012

David Winer and his friend, Gary Siegelman, visited our village of Kul'chiny last year. David, whose grandfather had a shop in Kul’chiny, was very interested in and wanted to learn about Jewish life in Kul’chiny in the past. Today, there are no longer any Jews in this village.

I organized a tour for David and Gary. On the tour, we met with an elderly village inhabitant named Yefgenia Babich. She had known many Kul'chiny Jews before WWII and was able to tell us about them.

In 1990, the head of the local agriculture cooperative, Anatoly Faidevich, decided to repair an old home across the road from the school and to make it into a medical and obstetric clinic. Specialists from Western Ukraine came to renovate the home. In the attic, they found documents that belonged to the former owner of the house, including check books, maps of property in the local forest that he owned, contracts for the sale of parts of the forest, etc. I took possession of them for safekeeping.

I showed the documents to David. They were signed by the owner, whose name was Abraham Gingold. Using an internet search, David found living members of the Gingold family. Abraham’s daughter had been saved from the Manevsti Forest massacre. Her father and brother were taken taken, with the other Kul'chiny Jews, to Antoniny, where they were seen by all the town inhabitants. They were then taken to the forest where they were killed.

After WWII, the young daughter, Bronislava, returned to Kul'chiny but she did not find any relatives. She went to L’viv a, where she eventually got married. David found that she and her family had emigrated to Israel in 1975. Bronislava Taibel (maiden name Gingold) is 86 years old. Her daughter lives in South Africa and her grand-daughter, Netta Lechtman, lives in Toront Canada. Bronislava asked me to send her father's documents to Israel.

David Winer was curious and asked why the village of Kul'chiny has no memorial for their Holocaust victims. He met with Nadezhda Faidevich, the village mayor. We will now be able to construct a memorial monument in Kul'chiny.

There were two prior visits by US citizens, descendants of Kul'chiners - Herbert Bixhorn and Joseph Resnick. My hope for the future is that we will have many more visitors - from the United States, Israel, South Africa, Canada, and other parts of the world. I plan to organize a more interesting and intensive tour. People must learn about the life of this village of Kul'chiny that, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, was a flourishing Jewish shtetl.

Copyright © 2012 David Winer