Rose Zwi's Story

By Rose Zwi 24 May 2006

In 1388 Grand Duke Vytautus officially endorsed the existence of Jewish communities throughout Lithuania by granting them a charter which spelled out their legal and religious rights. From time to time there were depredations on these rights, but that did not prevent them from contributing greatly, through enterprise and hard work, towards the country's development .

In Žagarė, for example, they created markets and fairs which became famous throughout Lithuania, increasing their number over the years to the benefit of the entire community. Its intellectual life flourished and it produced many famous rabbis, scholars and writers. Among other activities, they set up factories for processing bristles, candles, mead, wire and hides and conducted a brisk trade in flax, grains, metal, wines and machines. As economic conditions improved, the Jewish population expanded from 840 in 1766 to 5443 in 1897.

Despite occasional outbursts of anti-Semitism in Žagarė, usually instigated by the church, the Jews and gentiles functioned reasonably well together in a shared economy. By the early 20th Century, Jews identified themselves with Lithuania's struggle to free themselves from Tsarist oppression and to establish their long-suppressed cultural identity. The economy continued to expand until World War I, when the Tsarist authorities exiled the Jews from Žagarė and from other border towns and villages, deep into Russia and the Ukraine. The Jews had always been opposed to the oppressive Tsarist regime.

When they returned, after the war, Jews as well as their gentile neighbours, underwent a period of poverty and economic depression. The town had declined after the expulsion, and never regained its former vigour. But in February 1918 the Taryba proclaimed an independent Lithuanian state, and by 1921 had been accepted as a member of the League of Nations. Jewish Lithuanians, especially the younger generation, were drawn into the heady days of early Lithuanian independence. When Lithuanian became a signatory to a League of Nations' document for the protection of linguistic, racial and religious minorities, a Ministry of Jewish Affairs and a Jewish National Council had been set up in Kaunas; Jews served in the Lithuanian administration, in Parliament, and as officers in the army. Hebrew street signs even appeared in Kaunas. Some envisaged another Golden Age for the Jews.

But after a few years, the democratic process in Lithuania stalled. It became difficult to form stable governments. A coup d'etat in 1926 brought in an extreme nationalist government which curtailed civil liberties and abolished opposition parties. Parliament was dissolved in April 1927 and a temporary constitution was promulgated, abolishing important democratic principles of the original constitution. The rights of the Jews and other minorities had already been eroded before the coup: the "Golden Age" had lasted from 1919 to 1922. Economic anti-Semitism was also growing and the slogan "Lithuania for the Lithanians reverted to an insular policy which discriminated against minorities in Lithuania.

People began to leave the country where they had lived for generations, my mother's family among them. My father's family, however, remained in Žagarė.

I grew up among these immigrants whose songs and stories were steeped in nostalgia for their old home in Žagarė, Lithuania, which they called "der heim". Although I had never been there, it became my "home" as well. My childhood was filled with stories of swimming in the Svete in summer, and skating on it in winter; of walking through fragrant forests and fields and sledding in dazzling snow; of picking wild strawberries in the woods and strolling through Naryshkin Park on the Sabbath. As a child, I dreamed of returning to "der heim" one day.

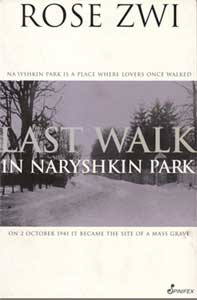

Then came World War II and darkness descended over Eastern Europe. When the war was finally over, news started trickling through about massacres and mass graves: Eventually it was revealed that ninety-five percent of the 220,000 Jews in Lithuania had been massacred, my father's family among them. My father, who left Lithuania after he married my mother in 1927, never forgave himself for "deserting" them. I grew up with the knowledge that had he and my mother not left in time, we too would have lain in the mass grave in Naryshkin Park. Survival imposes obligations, and I eventually began the long journey towards fulfilling my father's desire to propitiate the dead: I wrote Last Walk in Narishkyn Park.

In preparation for this I spent several years doing research in libraries and museums in New York, Israel and South Africa, interviewing survivors of the Holocaust, and reading books about Jewish life in Lithuania. I also read translations of articles in Lithuanian newspapers and articles by Lithuanian historians and scholars. Among the books was Lithuania: 700 Years, edited by Albertas Gerutis, (1984). I was shocked to discover that in a book of almost 500 pages, there were only three short references to the Jews who had lived in Lithuania since the fourteenth century, and who, between the two World Wars, had constituted seven percent of the total population. A mere six lines had been devoted to the Holocaust by Lithuanian historians and academics who do not mention that 95% of its Jewish population had been massacred under horrific circumstances, nor of the culpability of many Lithuanians in their deaths.

Not only had Jewish men, women and children suffered terrible deaths; they had also been expunged from Lithuanian history.

I shall only give one example of the silence and denial that is endemic among scholars, historians and academic on this subject. One of the chapters in Lithuania: 700 Years has the title Lithuanian Resistance 1940-52. The writer, Algirdas Budreckis chronicles the activities of the many resistance groups to Soviet rule, among whom the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) was prominent. He lauds their patriotism and heroism and freely admits that LAF "... was fully aware of the totalitarian nature of National-Socialism, but preferred to have Lithuania occupied by the Nazis than to be physically and economically destroyed by the colonial policies of the Soviet Union."

Budreckis does not mention LAF's leaflet No. 37, for example, issued in Berlin by the LAF and distributed throughout Lithuania just before the Nazis entered Lithuania. It begins with the statement that "... the crucial day of reckoning has come for the Jews at last. Lithuania must be liberated not only from Asiatic Bolshevik slavery, but also from the long-standing Jewish yoke." Among LAF's objectives is to revoke the "ancient right of sanctuary granted to the Jews in Lithuanian by Vytautas the Great," and states that it is the duty of all honest Lithuanians to take measures by their own initiative to punish the Jews, who are to be excluded from Lithuania forever.

This they proceeded to do with great vigour. A few days before the German occupation forces arrived, Lithuanians who defined themselves as freedom fighters. began a three-day killing rampage against Jews in smaller towns and villages. Budreckis reports only that LAF drove the remnants of the Red army out of Kaunas, but does not mention the massacre of the Jews. He writes: "By 6 p.m. on the 24th June, Kaunas was completely in the hands of the LAF... On June 24, the partisans began mopping-up operations against the large nests of Communist resistance, and within forty-eight hours, they had done likewise in the Kaunas suburbs."

The "mopping-up" operations included the murder of the entire population of over 150 Jewish communities, most of which became Judenrein 24 hours before the German occupation forces arrived. Four thousand Jews were massacred by the partisans in Kaunas alone. In Wilijampole (Slobodka) partisans went from house to house searching for Jews whom they threw into the River Vilija. Those who did not drown were shot as they swam. Jewish houses were set on fire and their occupants burned alive On June 25th, the partisans decapitated the Chief Rabbi of Slobodka, Zalman Ossovsky, and displayed his severed head in the front window of his house. His headless body was discovered in another room, seated near an open volume of Talmud that he had been studying. These killings, among others, were carried out in broad daylight, amid acquiescent, often cheering witnesses. When they attended mass in church, the partisans were praised by the priests for their courage and patriotism.

There were, however, a small number of clergymen who did not condone their countrymen's deeds and who even dared to condemn them and express their shame and pain.

I have given only one of many examples of the denial that exists among scholars, historians and academics who seem incapable of giving an unbiased perspective on history. Are not some facts incontrovertible? What of the documents, reports, diaries and testimonies by perpetrators and victims which point to the same facts? Like the Einsatzgruppen reports which meticulously list the massacres of Jews in towns and villages throughout Eastern Europe, including Žagarė, specifically referring to the invaluable help they received from local inhabitants. Is it possible to misinterpret or deny such facts?

We are entreated to learn from history if we are not to repeat its mistakes. How are we to learn from our mistakes if we do not acknowledge them, if we falsify and distort history by denying its painful aspects? In this way, long-discredited myths live on, fuelling the prejudices of successive generations.

A whole generation of Lithuanians has grown up with a skewed view of the role Jews played in the history of the country. Where they appear at all in history books or in learned articles, Jews are portrayed as a troublesome minority, alien to the native population, a disloyal element which allied itself with the Soviet regime that oppressed the Lithuanian people. Their positive contribution to the country in which they lived for centuries is seldom acknowledged. And when the massacre of 95 percent of Jewish Lithuanians is not entirely ignored or denied, it is justified with the absurd logic that Jews were Communists, Communists oppressed and deported tens of thousand of Lithuanians, therefore Jews were responsible for these crimes. The genocide of the Jews, when it is admitted, is held to be a natural reaction of the suffering they inflicted on ethnic Lithuanians.

It was therefore with some trepidation that I made my first visit to Lithuania in 1992. The one surviving member of my father's family was Leah, the pregnant wife of his younger brother Leib, who managed to get her out of Lithuania just hours before the Germans marched in. Leah spent the war on a kolkhoz in Russia, where she gave birth to her daughter Freda. Leib immediately joined the 16th Lithuanian Brigade and died in a battle against the invading Germans. My first pilgrimage to Žagarė was made together with my aunt Leah, her second husband Hirshl, their son Misha who drove us to Žagarė, and her daughter Freda. They all live in Vilnius. I give below excerpts from my book, Last Walk in Naryshkin Park which was published inAustralia in 1997. It has been translated into German, Chinese, with a Spanish edition to follow. Perhaps one day it will find a Lithuanian translator and publisher.

".... The countryside is flat. We pass clusters of thatched farm houses with sloping roofs, surrounded by fields of new wheat. Between them lie birch, pine and fire copses, remnants of ancient forests...

Ukmerge/Wilkomir, I read the road sign...

"That is your travel guide?" Freda asks as I page through Raul Hilberg's The Destruction of the European Jews, looking up the fate of Wilkomir's Jews.

"A very grim travel guide," I say. "It took four Aktionen to massacre the 4000 Jews of Wilkomir."...

The further north we travel, the darker the skies become. The mist, the sleet, the empty road; the sodden fields, the copses of birch and pine, combine to form the landscape of nightmare...

It is raining steadily as we follow the road into Panevezys. The Germans had reduced the place to rubble in 1941... After six Einsatzgruppen Aktionen, there were no Jews left in the town. .. The weather clears as we approach the town of Siauliai, also the name of the province in which Žagarė lies. The blue and white road sign indicates that road number A-216 lies ahead. The left turn-off leads to Žagarė, 80 kilometres from Siauliai; the right turn-off takes you to Ryga, a mere 16 kilometers away...

The scenery becomes increasingly rural as we approach Joniskis. As we drive out of the town, I see a street name on the wall of a wooden house: Žagarės Gatve, the street which leads to Žagarė. Thirty kilometres to go. We drive along a narrow tarred road with muddy shoulders, lined by tall, bare birches. This very road, unsealed, was travelled by my maternal grandfather Avram when he took his produce to town, and my paternal red-bearded grandfather Simon when he transported his passengers to Konigsberg. The trees may not have been there but the flat dark earth under slate grey clouds most certainly had. In this gloomy late winter weather, it is unimaginable that spring will ever transform the sodden fields into tall green wheat, jewelled with poppies and cornflowers.

Many years after my grandfathers had travelled here, peasants, silent and inscrutable as the landscape, must have watched the Siauliai fire brigade speed along this road to Žagarė, to flush away the blood of the massacred Jews from the cobbled market place. The River Svete, eye-witnesses later told me, ran red with their blood.

A rectangular road sign straddles a ditch: Žagarė. We have arrived. I photograph everything: All around us are bleak fields smudged with green, with clumps of leafless trees in the misty background. I record everything on camera. You can't rely on memory.

"This isn't Žagarė," Leah announces. "When you come into Žagarė, you go through the vald, the forest. And where is Naryshkin Park?"

"Perhaps we're still coming to the Park," Freda says.

There is nothing park-like in this desolate scene, only yellow winter grass and bedraggled pines and firs, weary from the weight of snow. Fifty meters on, Misha pulls up at a blue rectangular sign on the right side of the road. Its arrowed end points towards trees on the far side of the field.

" Fasizmo auku kapai, 0.2 – Memorial to the victims of fascism," Freda translates. "You will see these signs all over the country. Usually on the edge of forests where the massacres took place."

We come to a large area surrounded by trees, enclosed by a low wire fence. Three metal plaques soldered onto two iron posts stand near the gate. The top plate is in Lithuanian, the second in Yiddish, the third in Hebrew.

"In this place on 2 October 1941 the Hitlerist murderers and their local helpers massacred about 3000 Jewish men women and children from the Siauliai District."

Later I learned that Jews from Kursenai, Krakiai, Popilan, Joniskis, Zaimol, Radvilishkis, Linkuve and other places had been slaughtered here, together with the Jews of Žagarė. Local Lithuanians, the plaque recognises, had helped with the shooting...

To the left of the grave which is 120 meters long and the width of two people, is a three-stepped concrete plinth on which a roughly hewn obelisk stands... The obelisk is weather-worn, streaked with dirt and lichen. An icy wind soughs through the bare trees, freezing all emotion. We stand before the memorial in silence, dry-eyed, beyond tears, beyond prayer. Freda rights a small plastic fir tree in a plastic pot which has been blown over. At the base of the obelisk Leah leaves a stone, her heart....

"Our forests are planted with such graves," Freda says. "I know some Lithuanians did terrible things under the Nazis, but if I'm to live here, I have to accept that there are good Lithuanians and bad Lithuanians. I'm a Lithuanian myself. At a particular time of my life I looked at people of a certain age and thought, what did you do during the war? But one can't live like that."...

Before my parents married, my father had walked in Naryshkin Park with his Russian teacher, and my mother had kept trysts with her faithless lover who sailed away to Africa. Young men and woman had posed against the dark foliage for a photograph, looking the camera straight in the eye, as though defying the fate that would make the Park their burial place.

We parked the car and walked around Žagarė. We unsuccessfully approached several people to ask where we could find Daukante Gatve, where my mother and her family had lived. They looked at us suspiciously, with anger, and walked away. Had they thought we were the descendants of former residents who were trying to reclaim their homes? We eventually went into the municipal offices and explained our mission to the friendly manager. There is one Jew left in Žagarė, she told us, and put us in touch with Isaac Mendelson. We spent several hours with Isaac and his wife Altona who told us about the terrible fate of the Žagarė Jews. Like my uncle Leib, Isaac had also fought in the 16th Lithuanian Brigade, was badly wounded, and when he returned to Žagarė after the war, he discovered that his entire family had been massacred. He defied the antagonism of his former neighbours, stayed on in Žagarė, and married Altona, who had been a child of fourteen when the massacre occurred. It was she who told us in detail what had happened to the Jewish community.

"My family and other Lithuanians," said Altona, "just wanted to live in peace. We were used to living with the Jews. We'd been neighbours all our lives. When the Germans arrived, notices were pasted on all the walls, signed by the chief of the Lithuanian partisans. The Jews had to wear a yellow star..."

She lists all the restrictions imposed on the Jews. "Things got worse. Even before the Germans arrived, the leader of the Lithuanian partisans had asked for eighty young Jews to train for fighting the Germans. They were marched away and never seen again. (Isaac later takes us to the old Jewish cemetery where the young men were shot and buried in a mass grave.)

"We hardly saw the Germans," Altona says. "They were in Siauliai. The Lithuanian militia did it all. They said this was revenge against the Jewish Bolsheviks who had deported their families... The Jews were herded into a ghetto in July 1941 which had been set up on both sides of the Svete. Jews from surrounding towns and villages were brought into the Žagarė ghetto some weeks later. Most of them were women and children; their men had already been killed... It was impossible to live or sleep when these terrible things happened. Only the bad people slept well. All normal people were distraught..... we were threatened that if we sheltered Jews, our whole family would be shot. Everyone was afraid..."

"We did not witness the actual massacre," Altona says. "We

were warned to remain in our houses. But we heard the

shooting, the screaming. It went on for three days, first in

the market-place, later at Naryshkin Park. Afterwards we saw

the blood in the market-place. It took days to wash away. I

couldn't walk there. I always saw blood. Others felt the same.

That's why they made the market-place into a park, to cover it

up. I still dream about it, even though it happened so long

ago. I sometimes think we should rather have died with

them..."

I returned to Lithuania in the summer of 1993; my quest was incomplete. I had sought out my parents' contemporaries, interviewed survivors, travelled to Zhager/Žagarė, spoken to the one Jew in that town of ghosts, and worked in libraries, archives and museums. But apart from Altona, I had not spoken to other Lithuanians who had lived in Žagarė at the time of the massacre. The dour, hostile faces, and the air of menace that hangs over the town had made even the asking the street directions daunting. What would be their reaction have been to the questions I had come so far to ask:?

How could people, who had lived side by side for generations, turn on their neighbours or stand by as they were being massacred?

Had they really laughed and jeered when Jews were publicly humiliated? Had they protested when their Jewish neighbours were penned into the ghetto, starved and harassed by rampaging militia men? Was it indifference to their fate or fear for their own fate that had held them back? And when the Jews were finally driven to the slaughter, had a single shooter at the edge of the gaping pit, lowered his gun and refused to shoot? And had these killers been excommunicated by their Church for the slaughter of innocents?

A report from Einsatzgruppe A, dated 16 August 1941, sheds some light on the last question. Headed "Organisation of the Catholic Church in Lithuania, it states: "The attitude of the Church regarding the Jewish question is, in general, clear. In addition, Bishop Brisgys has forbidden all clergymen to help Jews in any form whatsoever. He rejected several Jewish delegations who approached him personally and asked for his intervention with the German authorities. In the future he will not meet with any Jews at all."

We are all made of the same stuff, I wanted to say to anyone in Žagarė willing to speak to me, and I want to believe that ancient hatreds, revenge for perceived transgressions, fear of the stranger, greed and envy, need not plunge ordinary people into the depths of savagery. Tell me something, anything, that will salvage my faith in people. Disillusionment in ideals is to feel bereft; loss of faith in humanity is to despair.

No one will speak to you, a Lithuanian friend living in the U.S. had written when I explained why I had to return to Lithuania. Lithuanian-language newspapers, she replied, were warning Lithuanians against speaking to outsiders about World War II events. Friendly interchanges, they said, had been exploited to malign the Lithuanian nation. One Lithuanian newspaper had reviewed a recent German film about the return of a Jewish survivor to the town of her birth, Butrimonys. She had come in search of a former Lithuanian militiaman who had shot many Jews in the area. The townspeople's negative reactions to the woman are recorded on film. So is the survivor's meeting with the militiaman. Although he is totally unrepentant, he has been rehabilitated by the Lithuanian government. The Lithuanian reviewer called the film a "slander against our nation."

To ask questions is not to slander a nation. An entire nation cannot be blamed for the evil actions of some of its people. It reflects badly on that nation, however, when convicted mass murderers are released from jail, rehabilitated and given pensions; when the press is openly anti-Semitic, and even worse, when there is complete denial of such events.

National pride, reluctance to confront an uncomfortable past and the need for help from the West has induced widespread amnesia in Lithuania. People have forgotten that they welcomed the German invasion in the mistaken hope that independence would be restored.

That there had been strong Lithuanian support for the Nazis, is not in doubt; meticulous German documents testify to this. The Lithuanian, Latvian and Ukrainian auxiliaries might only have been part players in the genocide of the Jews, but without them, the brutal killings orchestrated by the Einsatzgruppen under Himmler's command, could not have been carried out.

The Ypatinga Bura - the "special ones" - had murdered about 70 000 Jews at Ponary, near Vilnius. The 12th Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalion had killed Jews in Kaunas and Byelorussia. In addition to these special units, Lithuanian militiamen had participated in the murder of Jews in more than 200 cities, towns and villages throughout Lithuania. Such was their cruelty in Slutsk, for example that Gebiedskommissar Carl had complained about the "wild execution of Jews" to General-kommissar Kube of White Russia.

On my second visit, in the summer of 1993, my daughter and younger son accompany me to Lithuania. We are welcomed by the Mendelsons whom we contacted when we arrived in Vilnius. I learned from Isaac of a historian called Victoria who might be willing to talk to me. He makes an arrangement to meet at her home in two hours' time when she'll have completed her household chores. It is a beautiful summer's day and the people in the streets look relaxed and greet Isaac with a smile. He seems comfortable in their midst. Had I imagined the hostility, the menace of my last visit? Does the summer weather have to do with the lifting of mood?

Isaac takes my son and daughter to the mass grave and other places, while my cousin Freda and I go to Victoria's house. She is open and friendly, and gives permission for me to record our talk, as back up; Freda will translate for us. Her husband Domas, however, insists we switch off the recorder when he talks. She exhibits a historian's delight in detail and statistics when she is telling us about the history of the Naryshkins; she obviously has great respect for documentation.

Ask Victoria when the Jews first came to Žagarė, I say to Freda, leading up the questions I want to ask. In the nineteenth century, she replies, because it was a large trading centre where they could make money. She speaks with confidence. After all, she has taught this history for four decades. All the hotels and shops had been run by the Jews, she continues. A particular hotel attracted merchants from all over Lithuania because the owner brought in prostitutes from the other side of the river. My heart sinks. Is it too late to give the history teacher a history lesson?

Victoria, I would have said if language and circumstances had

permitted, there had been a settled Jewish community in Žagarė

by the sixteenth century. They hadn't flocked to Žagarė

because it was a flourishing market town; it was their

enterprise and hard work that made its markets and fairs

famous throughout Lithuania. But there seemed little point in

going on. Her teaching days were over.

I liked Victoria. She was friendly, warm, sincere. She did not

know much about the history of the Jews of Zhager, but by now

I have learned that historical sources are not easy to access,

especially if you are not looking for them. However, I

believed she would give me an honest answer to the question I

had travelled so far to ask:

"How could people, who had lived side by side for generations, turn on their neighbours or stand by as they were being massacred?"

She clutched her head and cried: "We must never forget it! The same happened in Panevyzs where I come from. Everywhere. It is difficult for me to say this, but the Jews were told lies. They were told they were being taken away to work. I cannot bear to speak about it," she said, covering her face. "The women and the children were beaten up and thrown onto lorries. The streets ran with blood. Streets of blood. People who saw this told me about it. Everyone was taken to Naryshkin Park where over 3000 Jews were shot. Every knows what happened. How is it possible to shoot another human being?"

By this time I am comforting her.

"I am an internationalist," she says, "not a leftist or a rightist, a fascist or a communist. It is very interesting for me to be speaking to Jews. As a historian I am very concerned with the reason for the murder of the Jews and who committed the murders. But I do not have access to the archives which would give me the answers. Without documents, it is impossible to know. But as a historian and as a human being, I believe no one should forget what happened."

It's a pity Victoria does not have access to the archives. Without documents she cannot tell who was responsible for the murder of the Jews.

"Did you get an answer to your question?" Isaac asked me afterwards.

"No," I told him, "but I haven't given up trying.

I make this contribution to the publication of a book to mark

the 1000th birthday of Lithuania, hoping that the publishers

will take this opportunity to correct at least a small part of

the skewed history of the Jews in Lithuania.