Anti-Semitism and Pogroms

by Ariel Parkansky

Russian Empire

Although hate against Jews has a long tradition in Christian history, anti-Jewish violence during 19th and 20th centuries in Russia in general and in Odessa in particular cannot be explained by that simple fact.

Actually, anti-Jewish violence in the Russian Empire before 1881 was a rare event confined mainly to Odessa where pogroms took place in 1821, 1859, 1871, 1881, 1886 and 1905.

While religious hate may have acted as a catalyst, economic and political factors were the main triggers of the different violent outbreaks against Jews, each one with its own actors and causes.

Indeed, “Russian” pogroms really started in 1881 while previous violence, not yet catalogued as pogroms, was “Greek” led.

1821: In Odessa, Greeks and Jews were two rival ethnic and economic communities, living side by side. The first Odessa pogrom, in 1821, was linked to the outbreak of the Greek War for Independence, during which the Jews were accused of sympathizing with the Ottoman authorities and of aiding the Turks in killing the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople.

1859: 1859’s pogrom, whose leaders and almost all of the participants were Greek sailors from ships in the harbor, and local Greeks who joined them, came right after the Crimean War (1853-1856).

Until that, Greeks controlled the export of grain from Odessa, while Jews dominated the roles of middleman and expediter. With the disruption of trade routes caused by the war, many of the leading Greek commercial firms either went bankrupt or decided to pursue other, more lucrative ventures. Jewish merchants and traders, who were accustomed to operating at smaller profit margins, filled the vacuum caused by the departure of Greek merchants and assumed prominent positions in the export business in Odessa, which was overwhelmingly dependent on the grain trade. Like other ethnic and religious communities in the city, Jewish merchants gave preference in employment practices to their coreligionists. Consequently, Greeks were supplanted by Jewish workers and fell into straitened economic circumstances. These developments, along with rumors of a Jewish ritual murder in 1859 generated the pogrom on the Christian Easter.

1871: Although the pogrom of 1871 was occasioned in part by a rumor that Jews had vandalized the Greek community's church, many non-Greeks participated to it. Russian resentment and hostility toward Jews came to the fore in the pogrom of 1871 as Russians joined Greeks in attacks on Jews. Thereafter, Russians filled the ranks of pogromist mobs in 1881, 1900, and 1905. The replacement of Greeks by Russians as pogromists reflects the decline of Greek influence in Odessa and underscores the tension and hostility that also existed between Russians and Jews in the city.

According to some Russian inhabitants, exploitation by and competition with Jews figured prominently as the causes of the 1871 pogrom. Some insisted that "the Jews exploit us," while others, especially the unemployed, blamed increased Jewish settlement in Odessa for reduced employment opportunities and lower wages. One Russian cabdriver, referring to the Jews' practice of lending money to Jewish immigrants to enable them to rent or buy a horse and cab, complained: "Several years ago there was one Jewish cabdriver for every 100 Russian cabdrivers, but since then rich Jews have given money to the poor Jews so that there are now a countless multitude of Jewish cabdrivers."

The 1871 pogrom was the first to attract national attention. A number of commentators in the Russian press presented the riot as a popular protest against Jewish economic exploitation of the native population. The Odessa pogrom led some Jewish publicists, exemplified by the writer Perets Smolenskin, to question belief in the possibility of Jewish integration into Christian society, and to call for a greater awareness of Jewish national identity.

The fact is that approaching the end of the 19th century, the growing visibility of Jews enhanced the predisposition Russians to blame Jews for their difficulties. The city's Jewish population had grown from approximately 14,000 (14 percent) in 1858 to nearly 140,000 (35 percent) in 1897 and the Jews had increased the importance of their role in the commercial and industrial life of the city. In the 1880s, for example, firms owned by Jews controlled 70 percent of the export trade in grain, and Jewish brokerage houses handled over half the city's entire export trade. Jewish domination of the grain trade continued to expand during the next several decades; by 1910 Jewish firms handled nearly 90 percent of the export trade in grain products. In addition to their activities as merchants, middlemen, and exporters, Jews in Odessa by century's end also occupied prominent positions in the manufacturing, banking, and retail sectors. In 1910 Jews owned slightly over half the large stores, trading firms, and small shops. Thirteen of the eighteen banks operating in Odessa had Jewish board members and directors, while at the turn of the century Jews comprised approximately half the members of the city's three merchant guilds, up from 38 percent in the mid-1880s. Jews virtually monopolized the production of starch, refined sugar, tin goods, chemicals, and wallpaper and competed with Russian and foreign entrepreneurs in the making of flour, cigarettes, beer, wine, leather, cork, and iron products. Even though Jews in 1887 owned 35 percent of all factories, these firms produced 57 percent of the total factory output (in rubles) for that year.

Like elsewhere in Russia and Western Europe, many non-Jews in Odessa perceived Jews as possessing an inordinate amount of wealth. While it is true that a number of Jews had a major stake on the economic, commercial and industrial life of Odessa, the vast majority of Jews eked out meager livings as shopkeepers, second-hand dealers, salesclerks, petty traders, domestic servants, day laborers, workshop employees, and factory hands. Poverty was a way of life for most Jews in Odessa, as it undoubtedly was for most non-Jewish residents. Isidor Brodovskii, in his study of Jewish poverty in Odessa at the turn of the century, estimated that nearly 50,000 Jews were destitute and another 30,000 were poverty-stricken. In 1905 nearly 80,000 Jews requested financial assistance from the Jewish community in order to buy matzoh during Passover, a telling sign that well over half the Jews in Odessa experienced difficulties making ends meet.

Furthermore, wealthy Jews could not enter the leisured propertied class or translate their wealth into political influence and power. Contrary to popular perceptions prevalent among non-Jews in both Odessa and throughout Russia, Odessa was not controlled by its Jewish residents. Only a handful of Odessa's Jews lived from investments in land, stocks, and bonds, and even fewer - 71 in a staff of 3,449 - worked for the imperial government, the judiciary, or the municipal administration. This was due in part to the 1892 municipal reform which made it more difficult for Jews to occupy government posts and disenfranchised Russian Jewry, who no longer enjoyed the right to elect representatives to city councils. A special office for municipal affairs was assigned the responsibility of appointing six Jewish members to the sixty-man Odessa city council.

1881: The pogroms of 1881 and 1882, which occurred in waves throughout the southwestern provinces of the Russian Empire, were the first to assume the nature of a mass movement.

The first one occurred in Elisavetgrad (Kirovgrad) in the Ukrainian province of Kherson on 15 April 1881 (27 April of Gregorian calendar) during the week following Easter; in the unsettled atmosphere created by the assassination of Emperor Alexander II on 1st March (13 March) 1881.

Typically, the pogroms of this period originated in large cities, and then spread to surrounding villages, travelling along means of communication such as rivers and railroads. Violence was largely directed against the property of Jews rather than their persons. In the course of more than 250 individual events, millions of rubles worth of Jewish property was destroyed. The total number of fatalities is disputed but may have been as few as 50, half of them pogromshchiki who were killed when troops opened fire on rioting mobs.

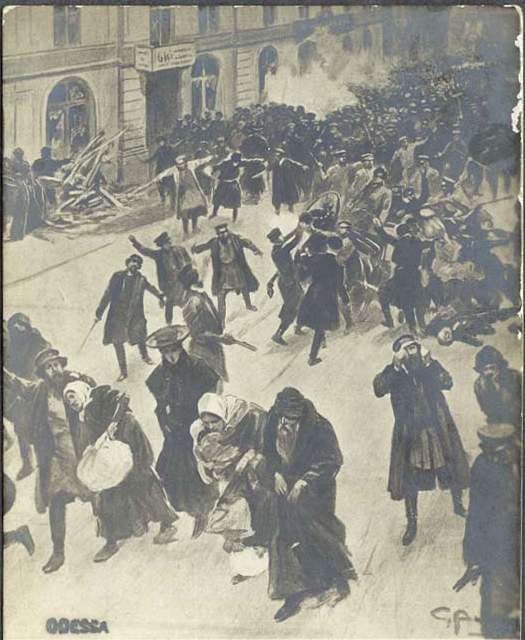

1905: The last pogrom in Odessa of the Russian Empire era was the one of 1905. This one occurred in the troubled times of the First Russian Revolution of 1905 and was the bloodiest one of all with 400 to 2500 Jews dead depending on the sources.

Postcard of 1905 Odessa Pogrom

source: jewishsphere.com

The revolution, which ended with the Tsar’s Manifesto of October 17th, came on a period of economic recession and political unrest boosted by the Russian-Japanese war of 1904-1905 lost by the Russians.

Increasingly powerful middle-class requesting access to political decisions, lower classes asking for food and money in a world crisis that had deeply touched Russian’s economy and peasant revolts due to bad harvest that had led to famines was a very fertile ground flavored with the hard repression imposed on demonstrators and strikers by the police and Cossacks.

Tsar’s Manifesto arrived as a response to the general unrest in Russia and pledged to grant civil liberties to the people: including personal immunity, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of association; a broad participation in the Duma; introduction of universal male suffrage, uncensored newspapers and a decree that no law should come into force without the consent of the state Duma.

When the news reached Odessa the following day, the Tsar’s statement that had intended to calm the population fueled instead demonstrations of joy of revolutionary groups that desecrated tsar effigies, showed banners and shouted anti-government slogans like "Down with the Autocracy”, "Long Live Freedom" and "Down with the Police". In several places demonstrators replaced Imperial flags by revolutionary red ones and forced passersby to doff their hats or bow before them.

Postcard of 1905 Odessa Pogrom

source: jewishsphere.com

“Extreme right” and “anti-revolutionary” groups organized then counter-demonstrations that quickly degenerated into violent clashes and attacks between pro and anti revolutionary followers.

Bolsheviks, worker unions, students and other protesting groups had a visible “Jewish” component. In addition, self-defense groups have been created in order to defend the Jewish population from anti-Jewish violence. Most of those groups were in some way armed.

This visibility converted the Jews as a whole in the responsible of the revolution and a legitimate target of anti-revolutionary mobs.

While it has not been proven (there are different interpretations between scholars) that government officials organized that violence, they took 3 days to react and stop the massacres tacitly approving them and holding Jews responsible of the revolution. According to eyewitness, some policemen participated to the violence while others didn’t prevent it.

WWI (1914-1918) and Revolution war (1917-1921)

While it’s hard to find specific information on Anti-Jewish outbursts and pogroms on Odessa during this period, it is certain that overall violence took its part there too as prove the pictures.

Portrait of a Jewish Self-Defense Group. (Odessa, April 1918)

source: yivo.org

During WWI, the notoriously Judeophobic Russian military was extremely brutal toward Jews, whether encountered as enemy aliens in the occupied Hapsburg territory of Galicia, or as Russian subjects in the Pale of Settlement. The policies of the Russian High Command during World War I included summary execution of Jews for alleged spying, the taking of hostages, and mass expulsions, at times on a province-wide basis. Taking their cue from these policies, military units, very often Cossack and other cavalry units, carried out pogroms against Jews throughout the war, with minimal interference by their officers. The actual number of Jewish victims is unknown, but the scale of Jewish suffering was immense.

During the Revolution war, like in 1905, Jewish visibility on Bolshevik movements made Jews as a whole responsible of the revolution that was called “Judeo-Bolshevik”, an amalgam used by all pogrom perpetrators, regardless of their affiliation

Odessa Jews killed in a pogrom during the Civil War.

source: berdichev.org

The Russian Civil War was fought on many fronts between 1918 and 1921. It was waged by disparate groups, motivated by politics (the Reds and the Whites), nationalism (Ukrainians and Poles), social protest (the agrarian Greens), and simple greed. The absence of any strong central authority ensured that the entire civilian population was victimized by one military force or another. All the contending armies conducted pogroms against Jewish communities. Only the commanders of the Red Army occasionally punished troops guilty of pogrom-mongering. The White forces often used anti-Semitism as a tool for ideological mobilization.

While ideology no doubt played some role in prompting pogroms, much of the violence was occasioned by the collapse of governmental authority, the brutalization caused by years of inhumane warfare, and a criminal desire to loot and plunder. There are sharply differing estimates on the total number of Jewish casualties during the Civil War, but the minimum credible estimate is 50,000 fatalities. Other reports talk about 2,000 pogroms having left an estimated of 100,000 Jews dead and more than half a million homeless.

WWII (1939-1945)

Before the war, Jewish population of Odessa had reached approximately 180,000 (30% of the total). By the time that the Romanians had taken the city, between 80,000 and 90,000 Jews remained, the rest having fled or been evacuated by the Soviets. As the massacres occurred, Jews from surrounding villages would be concentrated in Odessa and Romanian concentration camps set up in surrounding areas.

Although the facts are not doubted by historians, some accounts differ (often greatly) in the numbers, partially due to different definitions of what constituted the Odessa massacres, as opposed to other acts of genocide in Transnistria carried out by the Romanians, Germans, and their allies, including local Ukrainian authorities.

The official report on the Romanian role in the Holocaust states that in the city of Odessa from October 18, 1941 until mid-March 1942, the Romanian military, aided by local authorities, murdered up to 25,000 Jews and deported over 35,000, most of whom were later killed. The report also details 50,000 Jews killed in Bogdanovka, and tens of thousands more in Golta and the surrounding areas. The Jewish Virtual Library cites figures of 34,000 Jews murdered during October 22–25, and the US Holocaust Museum concludes that "Romanian and German forces killed almost 100,000 Jews in Odessa during the occupation of the city." In other sources the number of people killed in Transnistria was 115,000 Jews and 15,000 Gypsies

In any case, by 1942 only 703 Jews still lived in Odessa

Bibliography and Sources:

- Robert Weinberg, John D. Klier and Shlomo Lambroza, eds. (1992). "The Pogrom of 1905 in Odessa: A Case Study excerpts". Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History: 248–89.

- Wikipedia.org

- Yivo.org

- www.zionism-israel.com

- www.jewishencyclopedia.com

- www.ushmm.org

- www.berdichev.org

- www.massviolence.org