| 13. The Forced Labor Service | ||

|

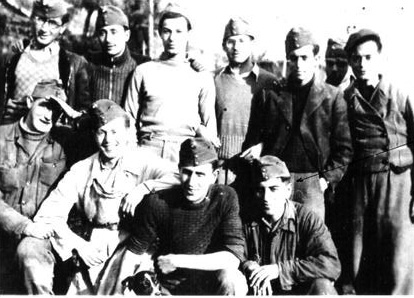

After the "dramatic confrontation" with Hori, the summer drew to a close, in an idyllic atmosphere, without further significant events. Our explanatory activity among the boys continued, from this time, in full accordance with Hori. This short period was a real summer camp. We were not forced to hide our activity and our relations with the boys from Hori. Only my call-up order as a "recruit" to the forced labor unit I received spoiled the happy mood of those days. I was ordered to report to the headquarters of the forced labor regiment in the Southern town Mohács on October 4, 1943. The town is located on the banks of the Danube, thus I used the boat service from Budapest to Mohács as a convenient means of travel. Luckily so, because the boat was crowded with recruits, like myself, heading for this doubtful experience of the Public Forced Labor Service. I soon discovered some comrades from our Movement and some more from the other, parallel movements among the crowd. My comrades from our Movement were Yehuda Wertheimer (one of my "roommates" in my first Heim in Budapest), Yoseph Meir, Yitshak Weinstock and Yaacov Markovitch. We decided to stick together, as much as possible, whatever should happen. Among the recruits were 12 more boys from the other movements who also joined us. The seemingly dominant person of the Maccabi Hatzair group was a tall, blond boy with clear, blue eyes and a face that revealed extraordinary intelligence. His personality intrigued my curiosity and we started small talk. Very soon we found out that we both were "sworn fans" of the Hebrew language and we automatically started to talk in this language. He started to "play" with my Hebrew name (we used only our Hebrew names in our movements) and after a few variations he "landed" with Jeshua - Jesus. From then on, this name stuck with me. This was the beginning of a true friendship with Yoseph Sheaffer that lasted for all the long months we spent together. On arriving to Mohács, a sergeant major and some sergeants lead the whole crowd to a nearby square where our names were read aloud for attendance check. Two groups were created, that turned into two companies, 4/3 and 4/4. 16 of our new comrades were in company 4/3. Only Y. Weinstock ("Ditzi") happened to be sent to the other company. The groups were separated and an officer stepped-up in front of the 4/4 company, presenting himself as Captain Kessler. He made a speech full of hatred and spiced with anti-Semitic remarks, something like: I am the commander of this company. You are not the first labor company I am going to command. I took my former company of Jews to the Russian frontier and very few of them lived to return. You are going to enjoy the same fate. Mind you, if you do not obey my commands and try to evade your duty, you will curse the day you were born! These words evoked indignant murmurs among his astonished future subordinates. He yelled furiously, "Shut-up, you dirty bastards!" and the silence was restored. His company marched off and we never saw them again. Then came another captain and addressed our company. He was captain Csutorás and spoke in a matter-of-fact tone, without referring to the base speech of his colleague. He declared that he demanded strict discipline and full obedience to all the members of the command staff and that he expected honest work from every one of us. We were very sorry for Ditzi and concerned about his fate. We were led to our "quarters", about the half of the company to the gym hall in the basement of an abandoned Jewish school, and the rest to an empty silk factory.

All the young Jewish men had to serve their compulsory military service in the Public Forced Labor service. We got no uniforms (a Jew was forbidden to wear the Royal Hungarian Uniform), only a military beret and an armband, yellow outside, for Jews and white inside, for renegades, which indicated that its wearer was a forced worker. We had to wear our civilian cloths and boots. There was no pay for the service, only a sparse compensation for the amortization of our clothes called "waste of clothes", paid every month. Instead of the usual rifle every soldier gets for the period of his military service, we got a new, shining personal shovel. On the next day we started or recruit training. We were organized in platoons and the platoons in squads, like the military. My new friend, Yoseph, being the tallest of his squad, had to be the first of his column. We were members of the same platoon and the sergeant of the platoon, Hostyánski called, "Jesus, you come here!" and placed me at the head of my squad, although there were some taller boys than me. The sergeant calling me by my new nickname indicated that even the staff men were aware of this and "accepted" it. This fact subsequently projected on my status within the company. These men were rather superstitious and this "mysterious" name had a certain impact on their attitude toward me. They always addressed me politely and never used harsh or obscene words when talking to me. I have to emphasize that somehow, I was a privileged exception and my personal story is, by no means, characteristic of the fate of forced laborers, even in my company. The circumstance surrounding my company were also far better than those in most similar units. This position at the head of the squad had its clear significance in the military hierarchy, it belongs to the "commander" of the squad, the lance corporal or the corporal and gives some trivial bonus. We underwent real recruit training, including extensive foot drills, using the shovel as if it were a real rifle. It was hard on those who lacked a former athletic background. Our recruit training lasted 6 weeks. The exercises were demanding and some of the platoon sergeants used the opportunity to abuse their subordinates. I was also lucky in this respect, because our platoon commander was considerate and avoided such excesses. Toward the end of our training, the company commander allowed visits by close relatives. Since none of my family could make this long journey, Tzipi decided to come, as my bride. Andy Vas, the son of a local Jewish physician was the only Mohácsi lad in our company; he was my "neighbor" in the squad next to mine. When I told him that my girlfriend was going to visit me, he asked that we be their guests for dinner after the visit (planned for the afternoon) and that she stay for the night. Thus, she would return to Budapest only on Monday morning. He also "whispered" the news into the ears of sergeant Hostyánszki. We were very glad to meet after this long separation (about 6 long weeks!). After the hours of visit we were allowed to escort our guests to the railway station or to the pier on the Danube. I led Tzipi to the Vas home, where she was most cordially welcome. On returning to the quarters, the sergeant called me and told me to be ready, because he had an important assignment for me that evening. Sometime later he called me to come with him. On our way, he admitted that we were heading for the Vas home in order to spend the evening with our respective girlfriends (he courted the maid of the house). The whole Vas family welcomed me gladly and all of us were invited to the delicious dinner that the kind Mrs. Vas had prepared for the occasion This was not my first dinner with this extraordinary family. Some weeks earlier Andy had invited me to have dinner with his family that wanted to meet me. He had a younger sister, a high school student of the last grade. She cared for Tzipi, prepared her room for the night. This time I enjoyed a delicious meal, nice people and, above all, some additional hours with Tzipi. All this I dare accredit to my weird and lucky nickname. Our training completed, we were moved to the district town, Pécs, and posted to the Commissariat of the Hungarian army. The company was divided again. The bigger part was sent to work with bundles of straw and hay, binding the bulk straw and hay from the stacks into bundles to build new, neat stacks. When military tracks came to fetch these materials, our men had to load them onto the tracks. It was hard work, mainly for those who were not used to physical labor. Most of our "Zionist" group was assigned to the storehouse, to handle sacks of various products, to load and unload them from and to tracks that were transporting them. The sacks weighed 60-100 kilograms (130-220 lbs) and we carried them on our backs or shoulders to the upper floor, on a shaky wooden stair flight or to the cellar, on a wooden spiral stair flight. The town boys had never tried to lift or carry sacks. Here I profited from my experience with sacks from years earlier when I worked with the threshing crew back in my hometown, Nagymegyer. Some of the boys were unable to shoulder a sack of 60-80 kg and we, some of the "villagers", help to shoulder their share, lest they be punished, until we managed to teach them the "secrets" of this trade. After a few days everyone mastered the techniques and we did what was expected from us. Placing the long sacks of flour (85 kg each) onto the crisscross stack demanded special skill. The few non-Jewish civilian workers in the storehouse, the heads of the crews, were rather alien towards us in the beginning and skeptic about our ability to overcome this seemingly unbridgeable difficulty. They eventually realized that we were determined to win this game and to prove to everybody that we were made of a substance unknown to them. They started to like us and even suggested to help in matters only outsiders could. They began to bring and buy special products for us, to supplement our menu. One of them also helped me to circumvent the harsh censorship of our outgoing and incoming mail. Because of this assistance I could correspond with my family and with Tzipi without the threat of the "watching eye" of the "censor", the deputy commander of the company. We soon started to treat the carrying of heavy sacks into games of sport: who of us could walk a longer section with two sacks of 85 kg on his shoulders, or mount the stairs to the upper floor, etc. The gentile onlookers shook their heads incredulously: men who never saw a sack, never ever touched one, would be willing and able to perform such bravura! Our prestige soared high in the eyes of our non-Jewish supervisors. We proved that this hard work that was aimed to humiliate and break us, was no more that a game for us! |

||